Abstract

EGFL7 is a secreted angiogenic factor produced by embryonic endothelial cells. To understand its role in placental development, we established a novel Egfl7 knockout mouse. The mutant mice have gross defects in chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis and placental vascular patterning. Microangiography and 3D imaging revealed patchy perfusion of Egfl7−/− placentas marked by impeded blood conductance through sites of narrowed vessels. Consistent with poor feto-placental perfusion, Egfl7 knockout resulted in reduced placental weight and fetal growth restriction. The placentas also showed abnormal fetal vessel patterning and over 50% reduction in fetal blood space. In vitro, placental endothelial cells were deficient in migration, cord formation and sprouting. Expression of genes involved in branching morphogenesis, Gcm1, Syna and Synb, and in patterning of the extracellular matrix, Mmrn1, were temporally dysregulated in the placentas. Egfl7 knockout did not affect expression of the microRNA embedded within intron 7. Collectively, these data reveal that Egfl7 is crucial for placental vascularization and embryonic growth, and may provide insight into etiological factors underlying placental pathologies associated with intrauterine growth restriction, which is a significant cause of infant morbidity and mortality.

KEY WORDS: Egfl7, Placenta, Branching morphogenesis, Endothelial dysfunction, Mmrn1, Gcm1

Summary: The endothelial-secreted protein EGFL7 plays a crucial role in placental development in mice, affecting chorionic branching, vascular patterning and fetal growth.

INTRODUCTION

The placenta provides the interface between the fetal and maternal circulatory systems during pregnancy, performing essential gas and nutrient exchange, as well as immunological and endocrine functions that are crucial for mammalian embryonic development. Proper development of the placenta requires coordinated maternal vascular remodeling and fetal vasculogenesis to bring the two circulatory systems into close contact. Defects in these processes can result in placental pathologies, including pre-eclampsia (PE) and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), which are leading causes of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality (Young et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2016a). Moreover, IUGR has been linked to significant morbidities later in life, such as coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus and hyperinsulinemia (Sharma et al., 2016b). Despite this, the molecular factors and signaling pathways controlling placental development remain incompletely understood.

The site of exchange between the mother and the fetus occurs in the chorionic villi in humans and in the analogous fetal labyrinth zone in mice. Labyrinth formation requires a series of morphogenetic events, including chorionic branching morphogenesis and subsequent blood vessel development (Rossant and Cross, 2001). The fetal vasculature of the placenta is derived from extra-embryonic mesodermal cells of the allantois. The allantois makes contact with chorionic trophoblast cells, which develop extensive folds into which blood vessels invade and interdigitate, forming a highly branched fetal vascular network of the mature placenta (Rossant and Cross, 2001; Watson and Cross, 2005).

Epidermal growth factor like domain 7 (Egfl7) encodes a secreted angiogenic factor whose expression is largely restricted to the endothelium in the developing embryo, and is downregulated in the adult quiescent endothelium. A long-standing controversy concerning the specific endothelial functions of Egfl7 and its intronic microRNA, miR-126, is based on conflicting results from knockout and knockdown studies in mice and zebrafish (Kuhnert et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). Earlier work demonstrated that specific loss of miR-126 in mice and zebrafish results in angiogenesis defects that were originally attributed to loss of function of Egfl7. Furthermore, egfl7 morphant zebrafish display severe vascular defects, whereas embryos of egfl7 mutant zebrafish and one Egfl7-specific knockout mouse line do not show obvious phenotypes, owing to activation of compensatory genes (Fish et al., 2008; Kuhnert et al., 2008; Nichol and Stuhlmann, 2012; Rossi et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2008). Conversely, endothelial-specific overexpression of Egfl7 in mice results in vascular defects during embryogenesis and pathological vascularization in the neonatal retina (Nichol et al., 2010; Bambino et al., 2014), suggesting a specific role for Egfl7 in vascular development.

Of importance for this study, Egfl7 is expressed in the inner cell mass and trophectoderm of mouse blastocysts, in the allantois, as well as in endothelial cells (ECs) and spongiotrophoblast cells of the developing placenta (Lacko et al., 2014; Bambino et al., 2014; Campagnolo et al., 2008; Fitch et al., 2004; Parker et al., 2004; Soncin et al., 2003). Egfl7 has been shown to promote migration of ECs and trophoblast cells (Campagnolo et al., 2005; Massimiani et al., 2015; Nichol et al., 2010). Its expression is downregulated in human pre-eclamptic placentas (Lacko et al., 2014; Junus et al., 2012), placentas of a mouse model of PE prior to the onset of clinical signs (Lacko et al., 2014), and in plasma of individuals with pregnancies affected by intrauterine growth restriction (Zanello et al., 2013).

Here, we have developed a novel Egfl7 loss-of-function mouse model (Egfl7−/−) that maintains miR-126 expression to study the functional role of Egfl7 during placental development. We demonstrate gross vascular patterning defects, EC dysfunction and feto-placental malperfusion at sites of narrowed fetal capillaries in Egfl7−/− placentas, which result in fetal growth restriction of Egfl7−/− embryos. We establish, for the first time, that Egfl7 loss of function results in dysregulation of genes that regulate chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis and labyrinth formation (Gcm1, Syna and Synb), and downregulation of the extracellular matrix gene Mmrn1. Our results demonstrate a crucial role for Egfl7 in normal development of the placenta and show vascular-specific defects in Egfl7-specific knockout mice.

RESULTS

Generation of Egfl7 loss-of-function mice

To analyze the function of Egfl7 during development, we generated a global Egfl7 loss-of-function mouse model that maintains expression of miR-126, the microRNA embedded in intron 7 (Egfl7−/−). Blastocysts were injected with an Egfl7 knockout embryonic stem cell clone (VelociGene modified allele ID1501) that was produced at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals using VelociGene methods (Valenzuela et al., 2003). A 13 bp region in exon 3 from the first ATG to 1 bp after the second ATG (5′-ATG CAG ACC ATG T-3′) in the targeted Egfl7 allele was replaced with a hygromycin LacZless-Poly-A-less cassette flanked by two loxP sites (Fig. 1A,B). Founder mice were backcrossed for ten generations into a C57BL/6J congenic background. Males heterozygous for the modified Egfl7 allele were mated with females carrying a CAG-Cre transgene (Sakai and Miyazaki, 1997), the Cre recombinase activity of which is maintained in mature oocytes regardless of Cre transgene transmission. Offspring with the excised hygromycin cassette that lacked the CAG-Cre transgene were intercrossed to obtain Egfl7−/− pups. Sequencing of genomic DNA from Egfl7+/+ and Egfl7−/− mice confirmed the Cre-mediated excision and deletion of the MQTM-coding sequence. The deletion leaves a single in-frame ATG (position 598 in the coding sequence) located C-terminal to the crucial functional domains of EGFL7, including the signal peptide, the EMI domain and the two EGF domains.

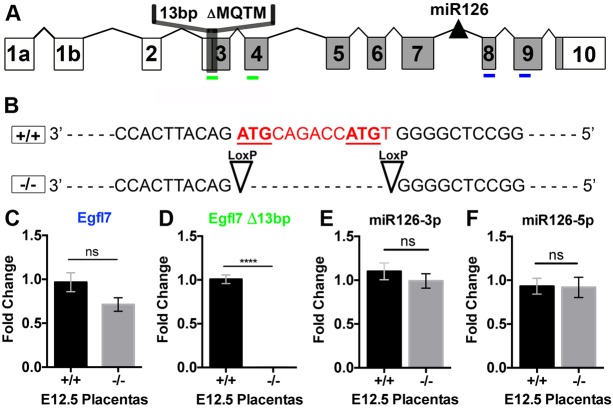

Fig. 1.

Generation of Egfl7 loss-of-function mice. (A) Schematic representation of the Egfl7 gene structure. Shaded regions represent protein-coding exons. The positions of the microRNA miR-126 and the 13 bp deletion in the mutant Egfl7 allele are depicted (not drawn to scale). Locations of primer sets are demarcated in blue (C) and green (D). (B) Sequence of the wild type (+/+) and modified (−/−) Egfl7 allele. The 13 bp deleted sequence is depicted in red with the two putative translational start sites underlined. (C,D) Real time RT-PCR for unmodified Egfl7 mRNA (C) and modified Egfl7 mRNA containing the 13 bp deletion (D) in E12.5 placentas from C57BL/6J (+/+, n=6) and Egfl7−/− mice (−/−, n=5). (E,F) Real time RT-PCR for miR126-3p (E) and miR126-5p (F) in E12.5 placentas from C57BL/6J (+/+, n=3) and Egfl7−/− (−/−, n=3) mice showing no change in miR-126 expression. Student's t-test; data are mean±s.e.m. ****P<0.0001.

To confirm the specific loss of Egfl7 and maintenance of miR126, we determined their expression levels. Egfl7 transcripts were measured in E12.5 placentas from C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− mice by real time RT-PCR using two sets of primers: one set complimentary to sequences in exons 8 (forward) and exon 9 (reverse) (Fig. 1A, blue); and a second pair with the forward primer containing the 13 bp sequence in exon 3 targeted for deletion in the Egfl7−/− mice and the reverse primer complimentary to a sequence in exon 4 (Fig. 1A, green). As predicted, Egfl7 transcripts containing exons 8 and 9 sequences were detected at similar levels in both C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− placentas. In contrast, the Egfl7 transcript that was amplified with the forward primer complimentary to the sequence encoding the two translational start sites was detected at high levels in C57BL/6J placentas, but was absent in Egfl7−/− placentas (Fig. 1C,D). Deletion of the translational start codon of Egfl7 is predicted to have no effect on production of miR-126. Indeed, real time RT-PCR of E12.5 C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− placentas demonstrates no significant difference in miR-126-3p and miR-126-5p expression levels (Fig. 1E,F).

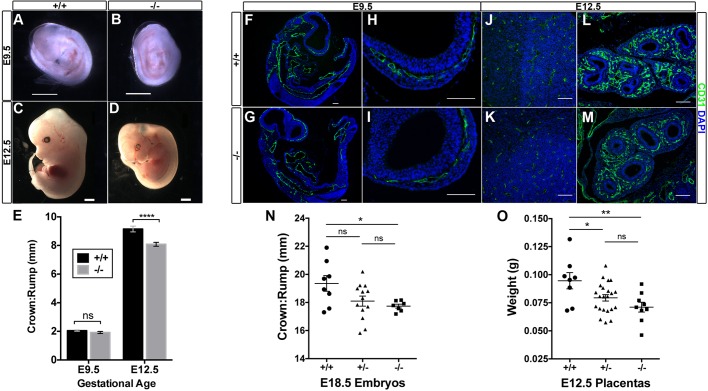

Egfl7 loss of function results in reduced placental weights and fetal growth restriction

Initial analyses of mice with the targeted allele were performed using Egfl7+/− intercrosses and comparing Egfl7−/− tissues with littermate controls. To exclude maternal contribution of a wild-type Egfl7 allele to the placenta of Egfl7−/− conceptuses, we performed all subsequent studies using Egfl7−/− intercrosses. Egfl7−/− mice from Egfl7+/− intercrosses were viable and born at the expected Mendelian ratio, demonstrating that abrogation of Egfl7 does not compromise embryonic viability; however, crown-to-rump lengths of Egfl7−/− embryos at late gestation were significantly decreased (19.4±1.6 mm versus 17.7±0.4 mm) (Fig. 2N). We next measured crown-to-rump lengths from control C57BL/6J×C57BL/6J (+/+) and Egfl7−/−×Egfl7−/− matings at E9.5, E12.5 and E18.5. Loss of Egfl7 did not affect crown-to-rump lengths at E9.5 (2.05±0.2 mm versus 1.92±0.3 mm) (Fig. 2A,B,E), the stage when Egfl7 expression peaks in the embryo (Fitch et al., 2004). By contrast, the lengths of Egfl7−/− embryos were approximately 1 mm shorter than C57BL/6J control embryos at E12.5 (9.15±0.8 mm versus 8.08±0.7 mm) (Fig. 2C-E), when Egfl7 expression in the placenta peaks (Lacko et al., 2014). Significant growth restriction of Egfl7−/− embryos was observed up to the final stages of gestation, at E18.5 (20.79±1.8 mm versus 18.80±1.4 mm) (Fig. S1A-C). To determine whether Egfl7 loss of function results in vascular patterning defects in the embryo, immunofluorescent staining was performed on sections of E9.5 and E12.5 embryos from C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− mice using the pan-endothelial marker CD31. No gross vascular defects or developmental delays were observed in Egfl7−/− embryos at either stage examined, including the vasculature of the developing head, heart, aorta, lung buds and intersomitic vessels (Fig. 2F-M; Fig. S1D-K), consistent with recently published studies in a different Egfl7 specific knockout mouse model (Kuhnert et al., 2008). Taken together, these results reveal a significant growth restriction of Egfl7−/− embryos after the onset of placenta development, suggesting placental insufficiencies as a possible cause of IUGR.

Fig. 2.

Egfl7 loss of function results in reduced placental weight and fetal growth restriction. (A-D) Representative images of E9.5 (A,B) and E12.5 (C,D) C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− embryos. (E) Quantification of the crown-to-rump lengths of E9.5 (+/+, n=23; −/−, n=21) and E12.5 (+/+, n=18; −/−, n=23) embryos showing a significant reduction in Egfl7−/− embryo lengths at E12.5, but not at E9.5 (Student's t-test). (F-M) Immunofluorescent staining for CD31 (green) and DAPI (blue) on sections of E9.5 and E12.5 C57BL/6J (+/+, F,H,J,L) and Egfl7−/− (G,I,K,M) embryos depicting no gross vascular defects. (F,G) Cross-section of whole E9.5 embryos. High-magnification images of the head vasculature at E9.5 (H,I) and E12.5 (J,K), and of the developing lung bud vasculature (L,M). (N) Quantification of the crown-to-rump lengths from Egfl7+/− intercrosses showing a significant reduction in Egfl7−/− embryo lengths at E18.5. (O) E12.5 placenta weights from Egfl7+/− intercrosses demonstrating a significant decrease in Egfl7+/− and Egfl7−/− placentas. Data are mean±s.e.m. One-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. ns, not significant. Scale bars: 1 mm in A-D; 100 µm in F-M. See also Fig. S1.

IUGR was first observed at E12.5, the developmental stage when the three layers of the mature placenta have formed and placental Egfl7 expression peaks, and continued to E18.5 (Fig. 2E, Fig. S1C). Strikingly, growth restriction at E12.5 coincided with a significant decrease in total weight of Egfl7+/− and Egfl7−/− placentas from Egfl7+/− intercrosses (+/+ 0.0946±0.02 g versus +/− 0.0794±0.01 g versus −/− 0.0711±0.01 g) (Fig. 2O). As growth restriction was also observed for Egfl7+/− and Egfl7−/− embryos (Fig. 2N), and similar weights were observed for male and female Egfl7+/− placentas from Egfl7+/− intercrosses when examined by PCR for Sry and Jarid (Fig. S1N), we can rule out predominant maternal effects or sexual dimorphism as the cause for the in vivo phenotype. Thus, our data demonstrate that Egfl7 plays an important role in placental growth, and indicate that placental defects may underlie the observed growth restriction in Egfl7−/− mutant embryos.

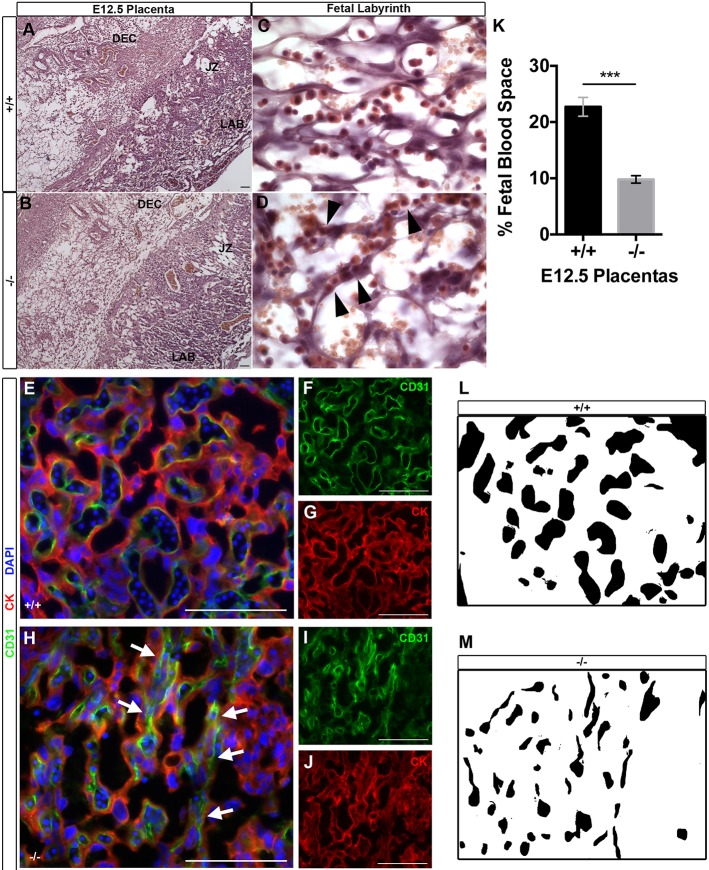

Egfl7−/− placentas exhibit vascular patterning defects and reduced fetal blood space in the labyrinth

To further investigate placental insufficiencies in mice with Egfl7 loss of function, we examined the morphology of Egfl7−/− and control placentas. Paraffin wax-embedded E12.5 Egfl7+/+ and Egfl7−/− placentas from Egfl7+/− intercrosses were sectioned, and placental morphology was assayed after Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (Fig. 3A-D). All three placental layers, including the maternal decidua, junctional zone and fetal labyrinth, formed in both Egfl7−/− and control placentas (Fig. 3A,B). Strikingly, at high magnification, the fetal labyrinth of Egfl7−/− placentas exhibited marked vascular patterning defects when compared with control placentas (Fig. 3C,D), whereas the maternal decidua and junctional zone showed no abnormalities (Fig. S1L,M). The maternal and fetal blood spaces are easily distinguished, as fetal vessels contain nucleated embryonic erythrocytes. A well-patterned fetal capillary network was revealed in the control placentas, consisting of open, lumenized, patent vessels adjacent to maternal lacunae, and separated by a thin layer of trophoblasts and ECs (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the fetal vessels in Egfl7−/− placentas were narrowed and markedly constricted (Fig. 3D). The reduced fetal blood space area resulted in accumulation of erythrocytes within the constricted blood vessels.

Fig. 3.

Vascular patterning defects and reduced fetal blood space in the fetal labyrinth of Egfl7−/− placentas. (A-D) Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections of E12.5 C57BL/6J (+/+) (A,C) and Egfl7−/− (B,D) placentas. (A,B) Low-magnification images depicting formation of three major placental layers: fetal labyrinth (LAB), junctional zone (JZ) and maternal decidua (DEC). (C,D) High-magnification images of the fetal labyrinth depicting narrowed fetal capillary space in Egfl7−/− placentas (arrowheads). (E-J) Double immunofluorescence staining for the pan-endothelial marker CD31 (green; F,I), the pan-trophoblast marker cytokeratin (red; G,J) and nuclear DAPI (blue; E,H) on placenta sections from E12.5 C57BL/6J (+/+; E-G) and Egfl7−/− (−/−; H-J) mice. High magnification of the fetal labyrinth zone is shown (E,H). Arrows mark narrowed fetal capillary spaces. (K) Quantification of the area of fetal blood space in the fetal labyrinth of C57BL/6J (+/+, n=3 placentas) and Egfl7−/− (−/−, n=3 placentas) mice from (E,H). (L,M) Representative images of fetal blood space area quantification demonstrating a significant decrease in the percentage of area covered by fetal capillaries in the fetal labyrinth zone of Egfl7−/− placentas (M). Student's t-test; data are mean±s.e.m. ***P<0.001. Scale bars: 100 µm. See also Fig. S1.

We next characterized the mutant phenotype of Egfl7−/− placentas by immunofluorescence analysis. Cryosections of C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− placentas from E12.5 conceptuses were assayed for expression of the endothelial marker CD31 and the pan-trophoblast marker cytokeratin. In Egfl7−/− placentas, ECs surround the irregularly patterned and narrowed fetal capillaries, whereas trophoblast cells lining the maternal blood spaces showed no obvious patterning defects (Fig. 3E-J). Quantification of the area of fetal capillary lumens revealed a significant reduction in fetal capillary blood space in the labyrinth of Egfl7−/− placentas (22.7±5.0% versus 9.8±2.0%) (Fig. 3K-M). Taken together, our histological and immunofluorescence analyses reveal that Egfl7 loss of function results in abnormal vascular patterning and reduced fetal blood space of the placental fetal labyrinth.

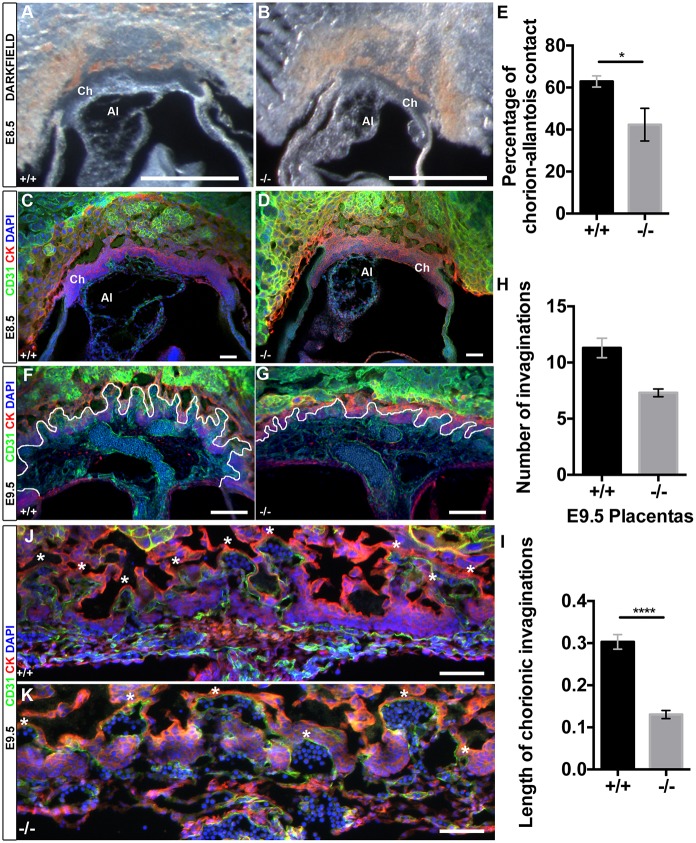

Egfl7−/− conceptuses show reduced chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis

Formation of the placenta and the fetal labyrinth begins at E8.5 when the allantoic mesoderm comes into contact with a flat chorion and initiates invaginations of the chorionic plate. Allantoic ECs then invade into the folds of chorionic trophoblasts and subsequently undergo branching morphogenesis to form the extensive vascular network of the fetal labyrinth (Rossant and Cross, 2001). Notably, Egfl7 is highly expressed by the allantois (Bambino et al., 2014). We next investigated whether Egfl7−/− placentas exhibit defects in chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis at this initial stage of placental development. To visualize chorioallantoic attachment in conceptuses at E8.5, we generated 100 µm vibratome sections of whole conceptuses (Fig. 4A,B). Results revealed that Egfl7−/− conceptuses contained a smaller allantois, which less efficiently covered the flat chorion when compared with stage-matched controls. Furthermore, Egfl7−/− allantoises did not exhibit the characteristic funnel-like shape seen in controls (Fig. 4A-D, Movies 1, 2). Quantification of the percentage of chorion covered by the attached allantois revealed Egfl7−/− allantoises covered 20% less of the chorion at E8.5 than controls (62.9±5.3% versus 42.3±13.5%) (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Egfl7−/− conceptuses show reduced chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis. (A,B) Representative dark-field images of 100 µm vibratome sections of E8.5 conceptuses from C57BL/6J (+/+) and Egfl7−/− mice. (C,D) Confocal images of 100 µm vibratome sections of E8.5 conceptuses from C57BL/6J (+/+) and Egfl7−/− mice, immunostained for CD31 (green), cytokeratin (red) and nuclear DAPI (blue), demonstrating a small allantois less efficiently adhered to the chorion in the mutants. (E) Quantification of the percentage of chorion that is attached to the allantois revealing a significant decrease in chorio-allantoic contact in Egfl7−/− conceptuses (+/+, n=5; −/−, n=4). (F,G) Confocal images of 100 µm vibratome sections of E9.5 conceptuses from C57BL/6J (+/+) and Egfl7−/− mice, immunostained for CD31 (green), cytokeratin (red) and DAPI (blue). Chorionic invaginations into which fetal vasculature is invading are indicated by a white line. (H,I) Quantification of the number (H) and length in mm (I) of invaginations in E9.5 placentas of C57BL/6J (+/+, n=3) and Egfl7−/− (n=3) mice. (J,K) High-magnification images of 10 µm cryosections of E9.5 placentas showing stunted and reduced number of invaginations in Egfl7 mutant placentas (K). Asterisks indicate each chorionic fold. Ch, chorion; Al, allantois. Student's t-test; data are mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, ****P<0.0001. Scale bars: 500 µm in A,B; 100 µm in C,D,J,K; 200 µm in F,G.

To visualize chorionic invaginations, immunofluorescent staining for CD31 and cytokeratin was performed on 100 µm vibratome sections of E8.5 and E9.5 conceptuses from C57BL/6J and stage-matched Egfl7−/− mice. Quantification of the number of invaginations and length of invaginations of the invading ECs into the chorion was performed on confocal z-stack images. Egfl7−/− placentas displayed significantly fewer (11.3±1.5 versus 7.3±0.6) and shorter (0.30±0.02 mm versus 0.13±0.01 mm) invaginations than control placentas (Fig. 4F-I, Movies 3, 4). Cryosections of C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− whole conceptuses were stained for CD31 and cytokeratin to analyze cellular detail of the invading blood vessels (Fig. 4J-K). Egfl7−/− invaginations were lined with CD31-positive ECs, but were stunted, widened and less organized when compared with controls. Thus, Egfl7−/− conceptuses display defects in branching morphogenesis at the initial stages of placental development.

Egfl7−/− placental endothelial cells exhibit defects in cell migration, sprouting and branching morphogenesis

To determine whether defects in EC function underlie the vascular phenotype observed in Egfl7 loss-of-function mutant placentas, we performed functional analyses of primary ECs isolated from Egfl7−/− and control placentas. Primary placental ECs were isolated from midgestation C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− placentas, and long-term placental EC cultures were established by infection with lentivirus expressing myristolated Akt, as previously described (Kobayashi et al., 2010; Poulos et al., 2015). Immunostaining for the endothelial markers CD31, Vecad and Erg, as well as for the trophoblast marker cytokeratin revealed that these cultures contained >99% ECs (Fig. S2A-F).

To examine migration of placental ECs, we performed a scratch wound healing assay, as previously described (Liang et al., 2007). A scratch wound was created in confluent monolayers of control and Egfl7−/− placental ECs, and cell migration was assayed by image analyses at 0 h and 24 h. Egfl7−/− placental ECs were significantly slower in migrating towards, and closing, the scratch wound at 24 h (Fig. 5A-E). The observed defect in wound closure was not due to changes in cell proliferation or apoptosis, as the percentage of Ki67-positive cells at 24 h and rates of proliferation in Egfl7−/− and control placental ECs were similar (Fig. S2G-J), and less than 0.5% caspase 3-positive cells were observed in either cell type (not shown). Consistent with these results, no significant difference in the number and percentage of proliferating endothelial and non-endothelial cells was observed between Egfl7−/− and C57BL/6J placentas in vivo, as determined by intraperitoneal injection of EdU and subsequent immunostaining for CD31, Erg and cytokeratin (Fig. S3).

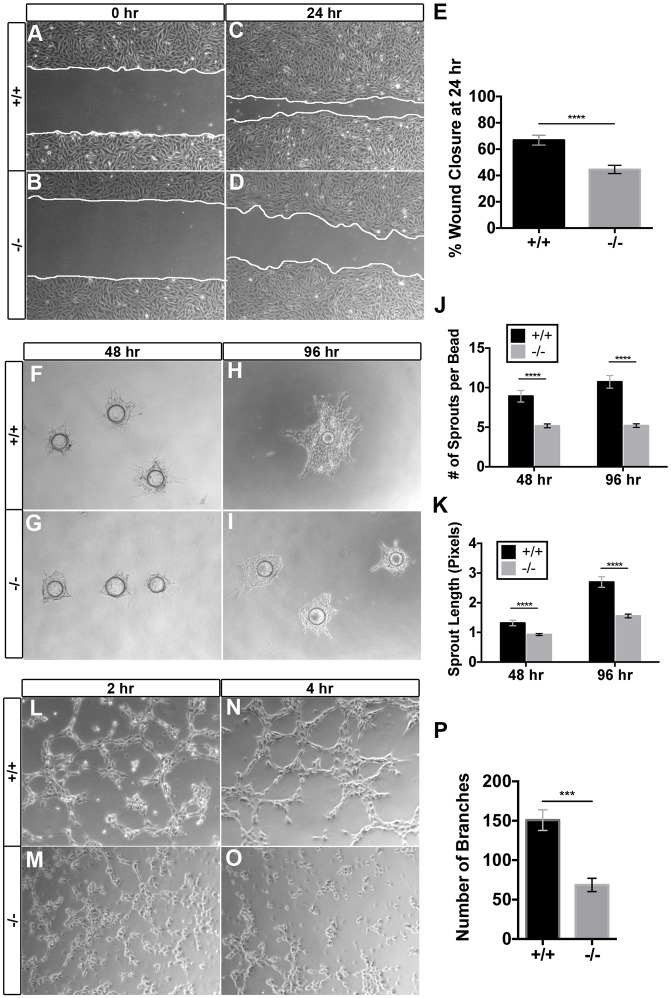

Fig. 5.

Egfl7−/− placental endothelial cells exhibit defects in cell migration, sprouting and branching morphogenesis. Isolated placental endothelial cells (ECs) from C57BL/6J (+/+) and Egfl7−/− mice were used for functional assays in vitro. (A-D) Representative images of the placental ECs from the scratch-wound assay. Collective EC migration was observed at 24 h (C,D). White lines indicate the leading edge of migrating cells. (E) Quantification of the percentage of wound area closed at 24 h (+/+, n=18; −/−, n=18). (F-I) Representative images of C57BL/6J (+/+) and Egfl7−/− placental ECs subjected to a bead sprouting assay, imaged at 48 h (F,G) and 96 h (H,I). (J,K) Quantification of the number of sprouts per bead (J) and the total sprout length (K) (+/+, n=11-12; −/−, n=20-23). (L-O) Representative images of C57BL/6J (+/+) and Egfl7−/− placental ECs subjected to a cord formation assay. Formation of cord-like structures on matrigel was observed at 2 h (L,M) and 4 h (N,O). (P) Quantification of the number of branches observed at 4 h, demonstrating a significant decrease in cord formation in Egfl7−/− placental ECs (+/+, n=20; −/−, n=15). Student's t-test; data are mean±s.e.m. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. See also Figs. S2 and S4.

To determine whether Egfl7 plays a role in placental EC sprouting, we performed a fibrin gel bead assay, an in vitro model that recapitulates key early stages of new vessel formation in a three-dimensional matrix, including vessel sprouting and maturation (Nehls and Drenckhahn, 1995; Tattersall et al., 2016; Nakatsu and Hughes, 2008). Egfl7−/− placental ECs formed significantly fewer and shorter endothelial sprouts when compared with control placental ECs at day 2 and day 4 in culture (Fig. 5F-K).

Finally, we assayed the ability of the placental ECs to form a capillary-like network using a cord formation assay (Kubota et al., 1988; Arnaoutova and Kleinman, 2010). Control and Egfl7−/− placental ECs were plated on growth factor reduced matrigel, and imaged after 2 h and 4 h. Control placental ECs formed a honeycomb-like network of connected EC cords beginning at 2 h and stabilizing at 4 h. In contrast, Egfl7−/− placental ECs completely failed to form a network of vascular cords and instead exhibited cellular clusters with fewer nodes or connections (Fig. 5L-O). Quantification of cord formation at 4 h showed a significant decrease in the number of branches (Fig. 5P). In contrast to the placental ECs, primary Akt-activated ECs from E10.5 C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− embryos did not show a significant difference in cell migration or proliferation (Fig. S4).

Our functional analyses of Egfl7−/− ECs have uncovered defects in placental EC function that are consistent with abnormal vascular patterning. Notably, these results corroborate the in vivo data showing an irregularly formed fetal vascular network in the placentas of Egfl7−/− mice.

Egfl7 knockout results in dysregulation of genes associated with chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis and in downregulation of the extracellular matrix protein Mmrn1

To elucidate the molecular mechanism by which Egfl7 regulates placental vascular development, we used a candidate gene approach. We first examined whether genes known to regulate chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis are dysregulated in Egfl7−/− mutants, given that Egfl7−/− placentas exhibit defects in this initial step of placental development. Specifically, we analyzed the expression of Gcm1, a transcription factor that is crucial for the initiation and maintenance of branching morphogenesis in the developing placenta. Gcm1 mutant mice display a complete block in chorioallantoic branching (Anson-Cartwright et al., 2000). Real time RT-PCR analysis was performed on C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− pre-placental tissues (chorion, ectoplacental cone and decidua) isolated from E8.5 conceptuses and from placentas at E9.5 and E12.5. Results showed Gcm1 transcript levels were significantly reduced in Egfl7−/− mutants at E8.5 and E9.5. At E12.5, Gcm1 levels were reduced without reaching significance (Fig. 6A). Immunohistochemistry for Gcm1 on E9.5 cryosections of C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− placentas revealed that Gcm1 protein localized in the nucleus and cytoplasm of trophoblasts at and between chorionic invaginations, and was reduced in Egfl7-null placentas (Fig. 6E-J).

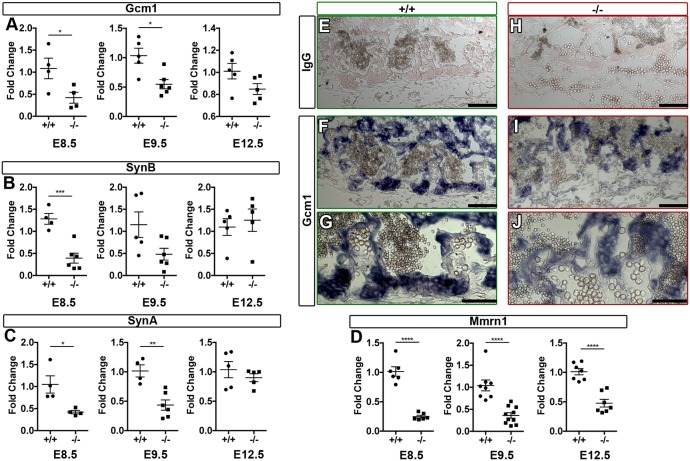

Fig. 6.

Egfl7 knockout results in dysregulation of genes associated with chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis and downregulation of the extracellular matrix gene Mmrn1. Real time RT-PCR for Gcm1 (A), Synb (B), Syna (C) and Mmrn1 (D) on pre-placental tissues (E8.5; chorion, ectoplacental cone and decidua) and placentas (E9.5, E12.5) from C57BL/6J (+/+, n=4-6) and Egfl7−/− (n=4-6) mice. Results demonstrate a significant decrease in gene expression for Gcm1 and Syna at E8.5 and E9.5, Synb at E8.5, and extracellular matrix gene Mmrn1 at all stages. Student's t-test; data are mean ±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. (E-J) Immunohistochemistry on E9.5 sections of C57BL/6J (+/+) and Egfl7−/− placentas for Gcm1 (purple precipitate) showing altered expression in Egfl7-null placentas. (E,H) IgG control staining for antibody specificity. (F,G,I,J) Gcm1 localization to chorionic invaginations. Scale bars: 100 µm in E,F,H,I; 50 µm in G,J. See also Figs. S5-8.

To further establish that Gcm1 signaling is dysregulated in Egfl7 loss-of-function placentas, we assayed for expression of the Gcm1 target gene Synb, which encodes an endogenous retrovirus envelope protein that plays a role in trophoblast fusion (Dupressoir et al., 2005, 2011). A concomitant significant decrease was observed for Synb transcript levels in Egfl7−/− pre-placental tissues at E8.5, while no significant difference was observed in E9.5 or E12.5 placentas (Fig. 6B). Notably, mice with a deletion in another endogenous retroviral envelope gene that is important for trophoblast development, Syna, display significantly reduced fetal blood space (Dupressoir et al., 2009). Syna expression was significantly decreased in Egfl7−/− pre-placental tissues at E8.5 and placentas at E9.5, and was unchanged at E12.5 (Fig. 6C). In contrast, no significant differences in expression of Itga4 and Vcam1, two key cell-adhesion molecules that are important for chorioallantoic attachment, were detected at E8.5, E9.5 or E12.5 (Fig. S8). Together, these results reveal that crucial regulatory genes involved in chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis are dysregulated early in Egfl7−/− placentas, which provides a molecular mechanism for the observed defects at the onset of placental development.

Previous studies have shown that Egfl7 modulates Notch signaling in vivo in mouse embryos and in vitro in HUVECs, human trophoblast cells and neural stem cells (Nichol et al., 2010; Massimiani et al., 2015; Schmidt et al., 2009). To examine whether Egfl7 modulates Notch signaling in the developing placental labyrinth, we performed real time RT-PCR for Notch target genes in pre-placental tissues (E8.5) or placentas (E9.5, E12.5) from C57BL/6J control and Egfl7−/− mice. Hey2 transcript levels were significantly reduced in E12.5 Egfl7−/− placentas when compared with C57BL/6J controls, and were unchanged at E8.5 and E9.5 (Fig. S5B). No significant difference was observed in mRNA levels of Notch target genes Hey1 and Hes1 in Egfl7−/− tissues at E8.5, E9.5 or E12.5 (Fig. S5A,C).

A recent study demonstrated compensatory roles for Emilin family genes (emilin3a, emilin3b and emilin2a) in egfl7 mutant zebrafish (Rossi et al., 2015). To determine whether Egfl7 loss of function in mice similarly results in changes in Emilin family gene expression, we performed real time RT-PCR for Emilin1, Emilin2, Emilin3, Mmrn1 and Mmrn2 on mouse pre-placental tissues, placentas and embryos from C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− mice. Results of these experiments revealed that Mmrn1 mRNA was significantly downregulated in Egfl7−/− pre-placentas at E8.5, and in placentas at E9.5 and E12.5 (Fig. 6D). Mmrn1 was the only Emilin family member that was dysregulated in extra-embryonic tissues at all stages examined. A small but significant decrease in expression of Mmrn2 and Emilin1 was found in Egfl7−/− placentas at E9.5 (Fig. S6B). Overall expression of Emilin3 was very low at all stages examined; however, a significant reduction was observed at E8.5 (Fig. S6A). No significant difference in expression of other Emilin family members (Emilin1, Emilin2, Emilin3 and Mmrn2) was detected at all other stages (Fig. S6). Furthermore, no significant changes were detected in Emilin family genes in Egfl7−/− mutant embryos at E9.5 and E12.5 (Fig. S7). In contrast to studies in zebrafish embryos, compensation by Emilin family genes was not observed in Egfl7−/− embryos or placentas.

To investigate whether a global reduction in gene expression is detected in Egfl7−/− placentas, we performed real time RT-PCR on two additional genes with differing roles in placentation, Hand1 and Vecad (Cdh5 – Mouse Genome Informatics) and found no significant difference in their expression at E8.5, E9.5 or E12.5 (Fig. S8D-F). Taken together, we have uncovered that dysregulation of specific genes, Gcm1, Syna, Synb and Mmrn1, underlies the observed defects in branching morphogenesis and labyrinth formation.

Altered vascular patterning results in reduced feto-placental perfusion in Egfl7−/− placentas

The aberrant vascular patterning and narrowed fetal capillary blood space observed in Egfl7−/− placentas raised the possibility that blood perfusion of the mutant placentas was compromised. To test this, we performed microangiography in control and Egfl7−/− conceptuses isolated at E12.5, and analyzed the three-dimensional architecture of the placental vasculature. In brief, whole E12.5 conceptuses were injected with a tomato-lectin solution into the umbilical artery to mark the blood-conducting vessels in the fetal labyrinth. Perfusion was restricted to the fetal labyrinth zone of the placenta. Analyses of 100 µm sections of C57BL/6J control placentas revealed a dense arborized vascular network of blood-conducting vessels in the fetal labyrinth (Fig. 7A,C-E). Large chorionic vessels at the base of the placentas branched into smaller vessels of the fetal labyrinth, and further into the dense capillary network in order to cover a large surface area (Fig. 7A). In contrast, Egfl7−/− placentas exhibited locally restricted and reduced feto-placental perfusion. The large chorionic vessels were well perfused. However, only sporadic areas with well-perfused, smaller branched vessels surrounded by areas of poorly perfused vessels were observed in Egfl7−/− placentas (Fig. 7B,F-H).

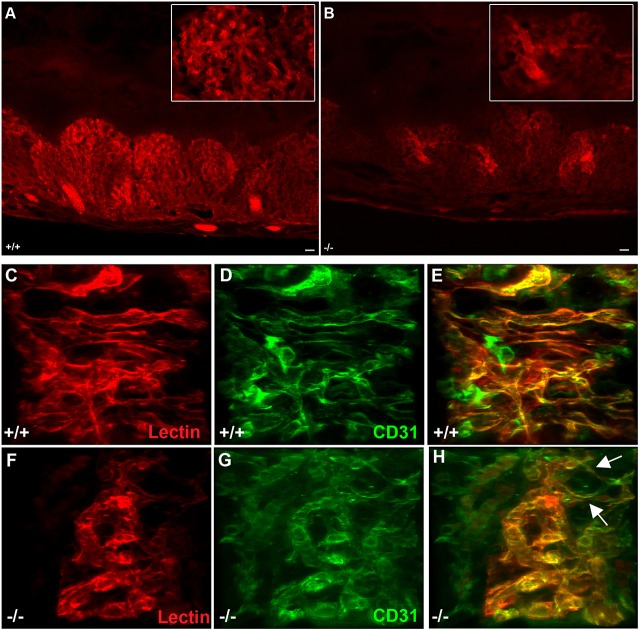

Fig. 7.

Altered vascular patterning results in reduced feto-placental perfusion at sites of constricted fetal capillaries in Egfl7−/− placentas. Microangiography of placentas from E12.5 C57BL/6J and Egfl7−/− mice was performed using tomato-lectin (red). Representative images of 100 µm vibratome cross-sections of E12.5 placentas from C57BL/6J (+/+; A) and Egfl7−/− (B) mice. Insets: higher magnification of representative images showing areas of reduced feto-placental perfusion in Egfl7−/− mice. (C-H) Three-dimensional reconstruction of z-stack confocal images of placentas perfused with tomato-lectin (red) and subsequently immunostained with CD31 (green). Arrows indicate narrowed fetal capillaries and areas where a reduction in perfusion begins. Scale bars: 100 µm in A,B.

To determine whether reduced conduction of blood results from constricted fetal capillaries lined by ECs and from vascular patterning defects, we performed retrospective immunofluorescence staining for CD31 on vibratome sections of placentas post-microangiography. Confocal imaging of the fetal labyrinth revealed a well-patterned perfused fetal capillary network lined by CD31-positive ECs with a smooth cell surface in C57BL/6J control placentas (Fig. 7C-E). In contrast, Egfl7−/− fetal labyrinth capillaries were tortuous, and their organization was markedly perturbed (Fig. 7F-H). A subset of these vessels was poorly perfused. Strikingly, results of these analyses revealed that sites of poor perfusion localized to small, narrowed or constricted fetal capillaries in Egfl7−/− placentas (Fig. 7F-H, Movies 5, 6). Together, our results show that Egfl7 loss of function results in abnormal vascular patterning of the fetal labyrinth, EC dysfunction and reduced feto-placental perfusion at sites of constricted fetal capillaries, all of which underlie intrauterine growth restriction.

DISCUSSION

Despite the crucial importance of the placenta for proper mammalian development, a complete understanding of the precise molecular pathways that are responsible for placental development and homeostasis remains largely elusive. However, considerable progress has been made through studying single gene mutations in mice (Rossant and Cross, 2001; Watson and Cross, 2005). Here, we show for the first time that Egfl7 is crucial for placental vascular development and embryonic growth. EGFL7 is a secreted, largely endothelial-restricted angiogenic factor that is associated with the extracellular matrix. We have generated a novel mouse model with loss of a functional Egfl7 gene, while fully maintaining expression of the intronic miR-126. The targeted allele in this study contains a deletion of the two translational start sites in exon 3, whereas the mutant allele described in a previous Egfl7 loss-of-function study deleted exons 5-7, leaving the start codons intact (Kuhnert et al., 2008). Our study firmly establishes that knockout of Egfl7 in mice results in abnormal chorioallantoic branching morphogenesis and vascular patterning of the fetal labyrinth, EC dysfunction and reduced feto-placental perfusion at sites of constricted fetal capillaries, all of which underlie IUGR.

The mutant phenotypes in Egfl7−/− placentas appear to be specific to the formation and patterning of the fetal labyrinth endothelium. In support of this, cultured placental, but not embryonic, ECs require Egfl7 for proper cell migration, sprouting and cord formation, suggesting that the primary defect is in ECs of the placenta. Furthermore, our studies indicate that maternal effects or sexual dimorphism do not contribute to the in vivo phenotype. Of note, we have recently reported novel sites of Egfl7 expression in junctional zone placental trophoblasts in mice and in cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts in human placentas, in addition to its expression in the fetal and maternal placental endothelium (Lacko et al., 2014). In fact, EGFL7 in human cultured trophoblast cells promotes migration and invasion through activation of NOTCH and EGFR signaling pathways (Massimiani et al., 2015). Future studies using trophoblast-specific knockout or knockdown of Egfl7 will address the possibility of non-cell autonomous and non-endothelial effects on branching morphogenesis in the labyrinth.

One striking result of our studies was the detection of vascular defects in the fetal labyrinth, and the lack of an overt phenotype in the embryonic or the adult vasculature. This could be explained by the developmental origin and/or the microenvironment of the ECs. The labyrinth EC lineage is derived from the extra-embryonic mesoderm of the allantois, whereas all embryonic and adult ECs are derived from the mesoderm of the embryo proper. In support of this, the transcriptome of placental ECs is distinct from that of ECs isolated from any other organ (Nolan et al., 2013) (J.M.B., unpublished). Furthermore, the labyrinth endothelium likely receives unique signals from its microenvironment, including trophoblast cells that are restricted to the placenta. Finally, previous studies have suggested a role for Egfl7 in the endothelium specifically during physiological stress, such as vascular injury (Campagnolo et al., 2005; Bambino et al., 2014). It is conceivable that pregnancy exposes the placental vasculature to similar stress-like challenges, resulting in placental insufficiencies in Egfl7−/− females.

The placental defects, together with the dysregulation of key pathway genes, are consistent with Egfl7 acting in both a paracrine and autocrine manner. During early stages of placental development, between E8.5 and E9.5, Egfl7 is prominently expressed in angiogenic progenitors and the emerging endothelium of the allantois (Bambino et al., 2014). Loss of Egfl7 results in defects in chorioallantoic attachment and branching morphogenesis, concomitant with significantly reduced expression of the key trophoblast-specific transcriptional regulator genes Gcm1, Synb, and Syna. Rescue experiments would be needed to verify that their decreased expression is the cause of the mutant branching phenotype. Interestingly, defects in chorionic branching morphogenesis are the leading cause of midgestation embryonic lethality in the mouse (Rossant and Cross, 2001). Our results suggest that allantois-derived EGFL7 is a crucial signaling factor specifically for branching morphogenesis and during early vascular development in the placenta, but not in the embryo. Importantly, allantois explants co-cultured with trophoblasts indicate that signals originating from the allantois initiate branching morphogenesis and induction of Gcm1 expression in the chorion (Cross et al., 2006; Downs and Gardner, 1995). Our results implicate the allantois-derived secreted EGFL7 to be such a paracrine signal.

The vascular patterning phenotype observed in Egfl7−/− placentas in vivo and in cultured placental ECs in vitro could be explained by an autocrine role of Egfl7, and may involve a poorly maintained extracellular matrix (ECM) structure. Previously, Egfl7 was reported to promote proangiogenic functions by inhibiting the formation of elastic fibers, thus reducing rigidity and influencing EC behavior through signaling to the ECM (Lelièvre et al., 2008). Members of the Emilin protein family (Emilin1, Emilin2, Emilin3, Mmrn1 and Mmrn2) are located predominantly in the ECM, are proangiogenic, and have been shown to modulate arterial blood pressure, elastogenesis and platelet hemostasis (Braghetta et al., 2004; Colombatti et al., 2000, 2011). Here, we show specifically that Mmrn1 expression is significantly reduced throughout placental development in Egfl7−/− mice. Mmrn1 has primarily been studied in humans for its role as a carrier protein for platelets (Jeimy et al., 2008; Tasneem et al., 2009); however, its precise role in the vasculature remains unknown. As Mmrn1 and Egfl7 are both associated with the ECM and share an EMI domain, it is possible that they interact and together exert an effect on the integrity of the ECM. Expression of other Emilin family genes was also significantly reduced in Egfl7−/− placentas at some, but not all, developmental stages examined (Mmrn2 and Emilin1 at E9.5; Emilin3 at E8.5). Intriguingly, Rossi and colleagues showed that the lack of vascular phenotypes in egfl7 mutant zebrafish could be explained by compensatory upregulation of emilin3a, emilin3b and emilin2a, and that emilin2 and emilin3 could rescue the vascular defects observed in egfl7 morphant embryos (Rossi et al., 2015). However, we did not observe upregulation of any of the known murine Emilin family genes in Egfl7−/− embryos, suggesting that potential compensatory mechanisms differ between mouse and zebrafish.

Our studies uncover, for the first time, a crucial functional role for Egfl7 in embryonic growth and in the developing placental vasculature in a loss-of-function mouse model that maintains miR-126 expression. These results provide novel insight into potential etiological factors underlying pathological placentation in humans, including IUGR and PE, which are leading causes of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Uteroplacental vascular insufficiency, the main cause of IUGR, results in chronic oxygen and nutrient deprivation. Fetal circulatory adaptations compensate for growth restriction, but also program the fetus for increased risk of hypertension, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes later in life (Osmond and Barker, 2000; Cohen et al., 2016). It would be of interest to determine whether the IUGR observed in Egfl7−/− embryos is linked to morbidities in the adult. Interestingly, elevated Egfl7 mRNA has been detected in maternal plasma of human pregnancies with early onset IUGR (Zanello et al., 2013). Given that EGFL7 is secreted, it will be important to determine whether the protein is detectable in the serum of pregnant women, and whether its expression is dysregulated in pregnancies with placental pathologies, including preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All animal protocols were approved and are in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Weill Cornell Medical College of Cornell University. C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Egfl7−/− mice were derived at the Mouse Genetics Core at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center from Egfl7 knockout embryonic stem cells (F1 [C57BL/6×126S6/SvEv] hybrid) provided by Nicholas Gale at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (VelociGene modified allele ID1501) through a Research Collaboration Agreement between Weill Medical College of Cornell University. A 13 bp region from the first ATG to 1 bp after the second ATG (5′-ATG CAG ACC ATG T-3′), was excised. See supplementary Materials and Methods for further information.

Founder mice were backcrossed into the C57BL/6J background for 10 generations to obtain congenic mice. For timed pregnancies, 8-10 week old mice were used with the date of the vaginal plug designated as E0.5.

Sequencing

Genomic DNA was amplified using specific primer sets surrounding the 13 bp deletion site, and purified samples were sequenced by the Cornell University Biotechnology Resource Center. See supplementary Materials and Methods for primer sequences and further information.

Immunohistochemistry

Placentas were isolated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in an OCT:30% sucrose mixture in PBS (2:1) or dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax for Hematoxylin and Eosin staining. For detailed staining protocols and antibody information, see supplementary Materials and Methods.

Microangiography

Females were sacrificed at E12.5 by cervical dislocation; conceptuses were isolated in L15 medium (Invitrogen) and umbilical arteries exposed. Tomato-lectin (Vector Labs, #DL-1177) (40 µl) in PBS containing heparin was injected into the umbilical artery. Each conceptus was incubated for 10 min at 37°C in L15 medium to allow the embryonic heart to circulate the injected dye throughout the feto-placental circulation. Placentas and embryos were then further dissected and fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde. Only conceptuses in which tomato-lectin had completely circulated through the placenta and reached the embryo were kept for analysis. Placentas were incubated in 5% low melt agarose for 2 h at 42°C, and embedded in 5% low melt agarose through solidification at room temperature. Blocks were cut on a vibratome at 100 µm. Agarose was removed and sections were either mounted in Prolong Gold (Life Technologies) using slide wells (Electron Microscopy Sciences) or processed for immunostaining. See supplementary Materials and Methods for further information regarding retrospective immunostaining.

Real-time RT-PCR

E8.5 pre-placental tissues (chorion, ectoplacental cone and decidua) and placentas (E9.5, E12.5) were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed using qScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Quanta Biosciences). Gene expression was measured quantitatively using PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix for iQ (Quanta Biosciences). Specific primer sets are listed in Table S1. For analysis of miR-126 expression, TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, 4366596) and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies, 4324018) were used. See supplementary Materials and Methods for further information on real time RT-PCR analyses.

EdU labeling

Proliferating cells were labeled using the Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit (Life Technologies, C10339) at E12.5 of gestation. See supplementary Materials and Methods for further information.

Placental and embryonic endothelial cell cultures

Placental and embryonic ECs were isolated and activated as previously described (Kobayashi et al., 2010; Poulos et al., 2015), from timed pregnancies of C57BL/6J control and Egfl7−/− matings at E10.5. Placentas and embryos were digested with Collagenase/Dispase (Roche) and ECs were immunopurified using CD31-captured magnetic beads (Life Technologies). Cultures were transduced with a myristoylated-Akt1 expressing lentivirus (Kobayashi et al., 2010), expanded and cultured on fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich)-coated plates. Purity was assessed by immunostaining. See supplementary Materials and Methods for further information.

Endothelial cell functional in vitro assays

Isolated endothelial cells were subjected to functional in vitro assays. For details on the scratch wound assay, the sprouting assay, the proliferation assay and the cord formation assay, see supplementary Materials and Methods.

Quantitative analysis of placental tissues

Fetal blood space area and morphological quantification was performed using Image J software. See supplementary Materials and Methods for further information.

Statistics

Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. The data were analyzed using Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. Statistical significance was defined as *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, or ****P<0.0001.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Nicholas W. Gale at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals for the mouse ESC clone containing the Egfl7 knockout allele. We thank members of the Stuhlmann Laboratory, including Abhijeet Sharma, Kathryn Bambino, Lissenya B. Argueta and Trevor Lee, as well as Drs Nicholas Gale, Jenna Schmahl, David Frendewey, Doris Herzlinger and Luisa Campagnolo for comments on the manuscript. We thank Drs Ian Tattersall and Jan Kitajewski for advice on the fibrin gel bead assay, and Drs Paula Cohen and Miguel Brieno Enriquez for advice on sex determination. Technical support was provided by the MSK Mouse Genetics Core Facility, Cornell University Biotechnology Resources Center and WCMC Optical Microscopy Core facility.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: L.A.L., H.S.; Methodology: L.A.L., R.H., S.H., M.G.P., J.M.B., H.S.; Software: L.A.L.; Validation: L.A.L., H.S.; Formal analysis: L.A.L., H.S.; Investigation: L.A.L., R.H., S.H., M.G.P., J.M.B., H.S.; Resources: R.H., H.S.; Data curation: L.A.L., R.H., H.S.; Writing - original draft: L.A.L., H.S.; Writing - review & editing: L.A.L., R.H., M.G.P., J.M.B., H.S.; Visualization: L.A.L.; Supervision: H.S.; Project administration: H.S.; Funding acquisition: R.H., H.S.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32 HD060600 to L.A.L., R01 HL082098 to H.S., and P20-103072 and R01-DK45218 to R.H.) and by the March of Dimes Foundation (6-FY14-411 to H.S.) Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.147025.supplemental

References

- Anson-Cartwright L., Dawson K., Holmyard D., Fisher S. J., Lazzarini R. A. and Cross J. C. (2000). The glial cells missing-1 protein is essential for branching morphogenesis in the chorioallantoic placenta. Nat. Genet. 25, 311-314. 10.1038/77076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutova I. and Kleinman H. K. (2010). In vitro angiogenesis: endothelial cell tube formation on gelled basement membrane extract. Nat. Protoc. 5, 628-635. 10.1038/nprot.2010.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambino K., Lacko L. A., Hajjar K. A. and Stuhlmann H. (2014). Epidermal growth factor-like Domain 7 is a marker of the endothelial lineage and active angiogenesis. Genesis 52, 657-670. 10.1002/dvg.22781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braghetta P., Ferrari A., De Gemmis P., Zanetti M., Volpin D., Bonaldo P. and Bressan G. M. (2004). Overlapping, complementary and site-specific expression pattern of genes of the emilin/multimerin family. Matrix Biol. 22, 549-556. 10.1016/j.matbio.2003.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnolo L., Leahy A., Chitnis S., Koschnick S., Fitch M. J., Fallon J. T., Loskutoff D., Taubman M. B. and Stuhlmann H. (2005). Egfl7 is a chemoattractant for endothelial cells and is up-regulated in angiogenesis and arterial injury. Am. J. Pathol. 167, 275-284. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62972-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnolo L., Moscatelli I., Pellegrini M., Siracusa G. and Stuhlmann H. (2008). Expression of egfl7 in primordial germ cells and in adult ovaries and testes. Gene Expr. Patterns 8, 389-396. 10.1016/j.gep.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E., Wong F. Y., Horne R. S. C. and Yiallourou S. R. (2016). Intrauterine growth restriction: impact on cardiovascular development and function throughout infancy. Pediatr. Res. 79, 821-830. 10.1038/pr.2016.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombatti A., Doliana R., Bot S., Canton A., Mongiat M., Mungiguerra G., Paron-Cilli S. and Spessotto P. (2000). The emilin protein family. Matrix Biol. 19, 289-301. 10.1016/S0945-053X(00)00074-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombatti A., Spessotto P., Doliana R., Mongiat M., Bressan G. M. and Esposito G. (2011). The Emilin/Multimerin family. Front Immunol 2, 93 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross J. C., Nakano H., Natale D. R. C., Simmons D. G. and Watson E. D. (2006). Branching morphogenesis during development of placental villi. Differentiation 74, 393-401. 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs K. M. and Gardner R. L. (1995). An investigation into early placental ontogeny: allantoic attachment to the chorion is selective and developmentally regulated. Development 121, 407-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A., Marceau G., Vernochet C., Bénit L., Kanellopoulos C., Sapin V. and Heidmann T. (2005). Syncytin-a and syncytin-b, two fusogenic placenta-specific murine envelope genes of retroviral origin conserved in muridae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 725-730. 10.1073/pnas.0406509102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A., Vernochet C., Bawa O., Harper F., Pierron G., Opolon P. and Heidmann T. (2009). Syncytin-a knockout mice demonstrate the critical role in placentation of a fusogenic, endogenous retrovirus-derived, envelope gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12127-12132. 10.1073/pnas.0902925106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A., Vernochet C., Harper F., Guégan J., Dessen P., Pierron G. and Heidmann T. (2011). A pair of co-opted retroviral envelope syncytin genes is required for formation of the two-layered murine placental syncytiotrophoblast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, E1164-E1173. 10.1073/pnas.1112304108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J. E., Santoro M. M., Morton S. U., Yu S., Yeh R.-F., Wythe J. D., Ivey K. N., Bruneau B. G., Stainier D. Y. R. and Srivastava D. (2008). Mir-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev. Cell 15, 272-284. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch M. J., Campagnolo L., Kuhnert F. and Stuhlmann H. (2004). Egfl7, a novel epidermal growth factor-domain gene expressed in endothelial cells. Dev. Dyn. 230, 316-324. 10.1002/dvdy.20063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeimy S. B., Fuller N., Tasneem S., Segers K., Stafford A. R., Weitz J. I., Camire R. M., Nicolaes G. A. and Hayward C. P. (2008). Multimerin 1 binds factor V and activated factor V with high affinity and inhibits thrombin generation. Thromb. Haemost. 100, 1058-1067. 10.1160/th08-05-0307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junus K., Centlow M., Wikström A.-K., Larsson I., Hansson S. R. and Olovsson M. (2012). Gene expression profiling of placentae from women with early- and late-onset pre-eclampsia: down-regulation of the angiogenesis-related genes ACVRL1 and EGFL7 in early-onset disease. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 18, 146-155. 10.1093/molehr/gar067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H., Butler J. M., O'donnell R., Kobayashi M., Ding B.-S., Bonner B., Chiu V. K., Nolan D. J., Shido K., Benjamin L et al. . et al. (2010). Angiocrine factors from akt-activated endothelial cells balance self-renewal and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 1046-1056. 10.1038/ncb2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y., Kleinman H. K., Martin G. R. and Lawley T. J. (1988). Role of laminin and basement membrane in the morphological differentiation of human endothelial cells into capillary-like structures. J. Cell Biol. 107, 1589-1598. 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnert F., Mancuso M. R., Hampton J., Stankunas K., Asano T, Chen C.-Z. and Kuo C. J. (2008). Attribution of vascular phenotypes of the murine Egfl7 locus to the microrna mir-126. Development 135, 3989-3993. 10.1242/dev.029736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacko L. A., Massimiani M., Sones J. L., Hurtado R., Salvi S., Ferrazzani S., Davisson R. L., Campagnolo L. and Stuhlmann H. (2014). Novel expression of Egfl7 in placental trophoblast and endothelial cells and its implication in preeclampsia. Mech. Dev. 133, 163-176. 10.1016/j.mod.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelièvre E., Hinek A., Lupu F., Buquet C., Soncin F. and Mattot V. (2008). Ve-statin/Egfl7 regulates vascular elastogenesis by interacting with lysyl oxidases. EMBO J. 27, 1658-1670. 10.1038/emboj.2008.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C.-C., Park A. Y. and Guan J.-L. (2007). In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2, 329-333. 10.1038/nprot.2007.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimiani M., Vecchione L., Piccirilli D., Spitalieri P., Amati F., Salvi S., Ferrazzani S., Stuhlmann H. and Campagnolo L. (2015). Epidermal growth factor-like domain 7 promotes migration and invasion of human trophoblast cells through activation of mapk, Pi3k and notch signaling pathways. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 21, 435-451. 10.1093/molehr/gav006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu M. N. and Hughes C. C. W. (2008). An optimized three-dimensional in vitro model for the analysis of angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol. 443, 65-82. 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02004-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehls V. and Drenckhahn D. (1995). A novel, microcarrier-based in vitro assay for rapid and reliable quantification of three-dimensional cell migration and angiogenesis. Microvasc. Res. 50, 311-322. 10.1006/mvre.1995.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol D. and Stuhlmann H. (2012). Egfl7: a unique angiogenic signaling factor in vascular development and disease. Blood 119, 1345-1352. 10.1182/blood-2011-10-322446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol D., Shawber C., Fitch M. J., Bambino K., Sharma A., Kitajewski J. and Stuhlmann H. (2010). Impaired angiogenesis and altered notch signaling in mice overexpressing endothelial Egfl7. Blood 116, 6133-6143. 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan D. J., Ginsberg M., Israely E., Palikuqi B., Poulos M. G., James D., Ding B.-S., Schachterle W., Liu Y., Rosenwaks Z. et al. (2013). Molecular signatures of tissue-specific microvascular endothelial cell heterogeneity in organ maintenance and regeneration. Dev. Cell 26, 204-219. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmond C. and Barker D. J. (2000). Fetal, infant, and childhood growth are predictors of coronary heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension in adult men and women. Environ. Health Perspect 108 Suppl 3, 545-553. 10.1289/ehp.00108s3545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker L. H., Schmidt M., Jin S.-W., Gray A. M., Beis D., Pham T., Frantz G., Palmieri S., Hillan K., Stainier D. Y. R. et al. (2004). The endothelial-cell-derived secreted factor Egfl7 regulates vascular tube formation. Nature 428, 754-758. 10.1038/nature02416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos M. G., Crowley M. J. P., Gutkin M. C., Ramalingam P., Schachterle W., Thomas J.-L., Elemento O. and Butler J. M. (2015). Vascular platform to define hematopoietic stem cell factors and enhance regenerative hematopoiesis. Stem Cell Reports 5, 881-894. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossant J. and Cross J. C. (2001). Placental development: lessons from mouse mutants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 538-548. 10.1038/35080570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi A., Kontarakis Z., Gerri C., Nolte H., Hölper S., Krüger M. and Stainier D. Y. (2015). Genetic compensation induced by deleterious mutations but not gene knockdowns. Nature 524, 230-233. 10.1038/nature14580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K. and Miyazaki J.-i. (1997). A transgenic mouse line that retains cre recombinase activity in mature oocytes irrespective of the Cre transgene transmission. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 237, 318-324. 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. H. H., Bicker F., Nikolic I., Meister J., Babuke T., Picuric S., Müller-Esterl W., Plate K. H. and Dikic I. (2009). Epidermal growth factor-like domain 7 (Egfl7) modulates notch signalling and affects neural stem cell renewal. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 873-880. 10.1038/ncb1896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D., Shastri S., Farahbakhsh N. and Sharma P. (2016a). Intrauterine growth restriction - Part 1. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 29, 3977-3987. 10.3109/14767058.2016.1152249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D., Shastri S. and Sharma P. (2016b). Intrauterine growth restriction: antenatal and postnatal aspects. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 10, 67-83. 10.4137/CMPed.S40070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soncin F., Mattot V., Lionneton F., Spruyt N., Lepretre F., Begue A. and Stehelin D. (2003). Ve-statin, an endothelial repressor of smooth muscle cell migration. EMBO J. 22, 5700-5711. 10.1093/emboj/cdg549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasneem S., Adam F., Minullina I., Pawlikowska M., Hui S. K., Zheng S., Miller J. L. and Hayward C. P. (2009). Platelet adhesion to multimerin 1 in vitro: influences of platelet membrane receptors, von Willebrand factor and shear. J. Thromb. Haemost. 7, 685-692. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tattersall I. W., Du J., Cong Z., Cho B. S., Klein A. M., Dieck C. L., Chaudhri R. A., Cuervo H., Herts J. H. and Kitajewski J. (2016). In vitro modeling of endothelial interaction with macrophages and pericytes demonstrates notch signaling function in the vascular microenvironment. Angiogenesis 19, 201-215. 10.1007/s10456-016-9501-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela D. M., Murphy A. J., Frendewey D., Gale N. W., Economides A. N., Auerbach W., Poueymirou W. T., Adams N. C., Rojas J., Yasenchak J. et al. (2003). High-throughput engineering of the mouse genome coupled with high-resolution expression analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 652-659. 10.1038/nbt822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Aurora A. B., Johnson B. A., Qi X., Mcanally J., Hill J. A., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R. and Olson E. N. (2008). The endothelial-specific microrna Mir-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev. Cell 15, 261-271. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson E. D. and Cross J. C. (2005). Development of structures and transport functions in the mouse placenta. Physiology (Bethesda) 20, 180-193. 10.1152/physiol.00001.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young B. C., Levine R. J. and Karumanchi S. A. (2010). Pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 5, 173-192. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanello M., Desanctis P., Pula G., Zucchini C., Pittalis M. C., Rizzo N. and Farina A. (2013). Circulating Mrna for epidermal growth factor-like domain 7 (Egfl7) in maternal blood and early intrauterine growth restriction. a preliminary analysis. Prenat. Diagn. 33, 168-172. 10.1002/pd.4034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]