Abstract

Objectives

Reflective writing has emerged as a solution to declining empathy during clinical training. However, the role for reflective writing has not been studied in a surgical setting. The aim of this proof-of-concept study was to assess receptivity to a reflective writing intervention among third-year medical students on their surgical clerkship.

Study Design

The reflective writing intervention was a one hour, peer-facilitated writing workshop. This study employed a pre-post-intervention design. Subjects were surveyed on their experience four weeks prior to participation in the intervention and immediately afterwards. Surveys assessed student receptivity to reflective writing as well as self-perceived empathy, writing habits and communication behaviors using a Likert response scale. Quantitative responses were analyzed using paired t-tests and linear regression. Qualitative responses were analyzed using an iterative consensus model.

Setting

Yale-New Haven hospital, a tertiary care academic center.

Participants

All Yale School of Medicine medical students rotating on their surgical clerkship during a 9 month period (74 in total) were eligible. In all, 25 students completed this study.

Results

The proportion of students desiring more opportunities for reflective writing increased from 32% to 64%. The proportion of students receptive to a mandatory writing workshop increased from 16% to 40%. These differences were both significant (p=0.003 and p = 0.001). 88% of students also reported new insight as a result of the workshop. 39% of students reported a more positive impression of the surgical profession after participation.

Conclusion

Overall, the workshop was well-received by students and improved student attitudes towards reflective writing and the surgical profession. Larger studies are required to validate the effect of this workshop on objective empathy measures. This study demonstrates how reflective writing can be incorporated into a pre-surgical curriculum.

Keywords: Narration, Empathy, Education (Medical — Undergraduate), Education (Medical — Graduate)

Introduction

Does surgery have an empathy problem? The answer, at least relative to other medical specialties, seems to be yes. Surgeons rank lowest on measures of empathy (1) and communication (2). Furthermore, surgery attracts the least empathetic medical students to the field (3). There may be good reasons for the discrepancy: surgeons spend more time in hospitals, deal with higher acuity of illness, and aren’t able to spend as much time in clinic forming relationships with patients compared with other specialties. There also may be a perception that empathy is neither required for a surgical trainee nor valued as an important trait and therefore is not modeled by faculty members. Nonetheless, a lack of empathy is unequivocally problematic for patient care. Lower empathy scores are associated decreased patient satisfaction (4), increased provider burnout (5) and worse patient outcomes (6, 7).

Why are empathy scores for surgeons so low? Studies on the subject report that empathy, for all medical specialties, depreciates during training, and in particular during medical school. In one longitudinal study, student empathy peaked in the preclinical years, followed by a considerable drop in the clinical year (3). The drop was particularly precipitous for those entering ‘technology-oriented specialties’, such as surgery. The authors conclude that pre-surgical trainees not only start out less empathetic, but have higher rates of empathy attrition during the clinical years in medical school.

Reflective writing, defined here as “writing with the goal of finding significance in personal experience”, has emerged as an intervention for preventing empathy decline among medical trainees (8). Reflective writing exercises have been studied in various forms, including personal incident reports (9), journal writing (10), or essay assignments (8). The rationale for incorporating reflective writing into medical training is that reflective writing may help trainees consider patient perspectives by dissecting individual patient encounters. Indeed, a meta-analysis of 8 studies supports this, finding a uniform increase in empathy among students after participation in a reflective writing intervention (11).

Despite the relative consensus in the utility of reflective writing in fostering empathy, little work has been done examining the role for such interventions in a surgical setting. Given the high attrition of empathy during the clinical year among pre-surgical trainees in medical school, we propose a novel writing workshop for medical students on their surgical clerkship. In this proof-of-concept study, the student response to this intervention and changes in student perception of surgery were examined over a 9 month period among 80 medical students.

Methods

Study participants

Participation was solicited by email among medical students on their surgical clerkship at the Yale School of Medicine (New Haven, CT) in a 9 month period (80 medical students total). The study was granted institutional exemption under code 45 CFR 46.101(b)(1): research investigating an educational practice in an educational setting.

Workshop administration

The intervention was a one hour, peer-led, real-time, reflective writing workshop. Author G. L. (a medical student at the time of data collection) led all workshops. The workshop was held during the surgical clerkship’s protected didactic time in the last three weeks of the twelve-week long clerkship to allow students to gather sufficient clinical experience upon which to reflect and represented a new addition to the Yale school of medicine didactic curriculum. All students on their surgical clerkship were required to attend. Approximately twenty five students were seated at a conference table, and no attending faculty were present. The contents of the workshop are depicted in detail (Table 1). Briefly, the workshop began with an introduction from the workshop facilitator. This introduction consisted of an explanation of the workshop and its rationale, as well as three rules for establishing a ‘safe space’ for reflection: 1) a confidentiality pledge 2) a commitment to active listening to peers and 3) a commitment to refrain from judging peers’ writing as “good” or “bad”. This introduction was followed by three phases of writing. Each phase called upon more detailed reflection from events that occurred more remotely in time. Thus, the first phase consisted of short-form (e.g. a few words or a sentence only) recollection of events from the day of the workshop. By contrast, the last phase consisted of a long-form (e.g. several paragraphs) of a patient encounter anytime since the beginning of the clerkship (up to 2 months prior). The rationale for this phasic format was to improve recall of repressed or forgotten experiences as well as decrease intimidation among those without writing experience. Additionally, students were given time to share writing at several junctures during the workshop. Finally, all writing was strictly timed to ensure that the workshop did not exceed the allotted one hour.

Table 1.

Writing workshop rubric.

| Phase | Workshop Item | Time allotment (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | 3 | |

| 1) Short-term recall | A) Prompt: Write about the most boring moment of your day. | 1 |

| B) Prompt: Write about the proudest moment of your day. | 1 | |

| C) Prompt: Write about the weirdest moment of your day. | 1 | |

| 2) Long-term short form recall | A) Complete this sentence with a list: since being on the surgical clerkship I have become more… | 1 |

| B) Complete this sentence with a list: since being on the surgical clerkship I have become less… | 1 | |

| Students share either 2A or 2B (all students) | 3 | |

| C) List some things that you’ve done on the surgical clerkship that you had never done before in your life. | 2 | |

| D) List the most rewarding moments you’ve had on the clerkship so far. | 2 | |

| Student shares either 2C or 2D (all students) | 3 | |

| 3) Long-term long form recall | A) List the initials of patients who have stood out to you in the last two months. If you can’t remember a patients initials, write some distinguishing feature that will jog your memory of them. | 2 |

| B) Next to each set of initials, write the first word that comes to mind. | 1 | |

| C) Circle one word that stands out to you. Write about that particular patient, using the circled word in the first sentence of your prompt. | 8 | |

| Students shares 3C (volunteer-basis) | 20 | |

| Closing comments from students (all students) | 10 | |

| Total: 60 |

Survey administration

To assess degree of change, student response was assessed in a pre-intervention/post-intervention study design. Four weeks prior to participation in the workshop, students were invited to participate in a survey (Table 2) by email. The survey consisted of a series of statements with which subjects rated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale. The responses were collected using the Web-based client Qualtrics (Qualtrics, inc; Provo, UT). The survey statements inventoried a number of domains including reflection, empathy, writing and communication. Also, the level of desire for reflective writing was assessed. Immediately following the workshop, a second post-intervention survey was circulated. The survey contained the same Likert statements, but additionally included three free-form responses.

Table 2.

Surveys administered prior to and after participation in the writing workshop.

| Survey | Survey Item |

|---|---|

| Pre and post-intervention surveys. “Please indicate your agreement with the following statements.” | I think reflection is one of the most important parts of medical training. |

| I find I have enough time during my third year clerkships to process my experiences. | |

| I consider myself to be an empathetic person. | |

| I have been writing reflectively (e.g. keeping a diary, writing notes) regularly during my clerkships. | |

| I would like to find more time to write reflectively. | |

| I often talk about troubling experiences in the hospital with others. | |

| I would like more opportunities for reflective writing during the clerkships. | |

| I would welcome a required writing workshop during didactic time in third year. | |

| Post-intervention survey only | Please specify something that you learned about yourself during this workshop. If you did not learn anything, please write “nothing”. |

| Please specify something that you learned about your peers during this workshop. If you did not learn anything, please write “nothing”. | |

| Did this workshop change your perception of the surgical clerkship? If it did, please specify the way(s) in which it did. If it did not, please write “it did not”. |

Qualitative analysis

An iterative consensus process was used to analyze free-form responses. Two reviewers (G. L. and O. J.) independently coded responses to form a set of themes. After independent coding, both reviewers met and arrived at a final set of themes. An additional rating was performed for one of the three free-form questions: “Did this workshop change your perception of the surgical clerkship? If it did not, please write ‘it did not’.” For this question, reviewers independently rated comments as positive change in perception, negative, or no change. For example, a comment about how the workshop humanized the perception of the surgical profession would be rated as positive change in perception, whereas a comment about how the workshop reminded them of the poor bedside manner of surgeons would be rated as negative. In the case of disagreement of ratings between reviewers, the response was placed in the more negative category.

Statistical analysis

Considerable debate exists as to the appropriateness of using parametric tests on ordinal variables such as Likert responses (12). However, the only study, to our knowledge, that calculates the alpha and beta error of parametric tests on ordinal variables finds lower rates of error in both categories as compared with their non-parametric equivalents in simulated datasets (13). For this reason, in this study, parametric tests were employed. Statistical tests were performed in the SPSS statistical package (IBM; Armonk, NY). Paired t-test statistics were calculated to assess differences among Likert responses before and after intervention and Pearson correlation to determine the relationship between Likert responses to individual statements. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used at the cutoff for significance. Divergent stacked bar charts to display raw Likert response data were generated in R (Free Software Foundation; Boston, MA) using the ‘HH’ statistics package. Scatterplot generated in SPSS (IBM; Armonk, NY). All other graphs were generated in Numbers (Apple Inc; Cupterino, CA).

Results

Participation was solicited from 80 medical students. Pre-intervention surveys were completed by 44 students. Of these 44 students, 25 students successfully completed the post-intervention surveys as well (31% total response rate). Data collected from these 25 students were used for analysis. One student who completed both surveys omitted responses to four questions in the post-intervention survey. This subject’s completed responses were used for analysis.

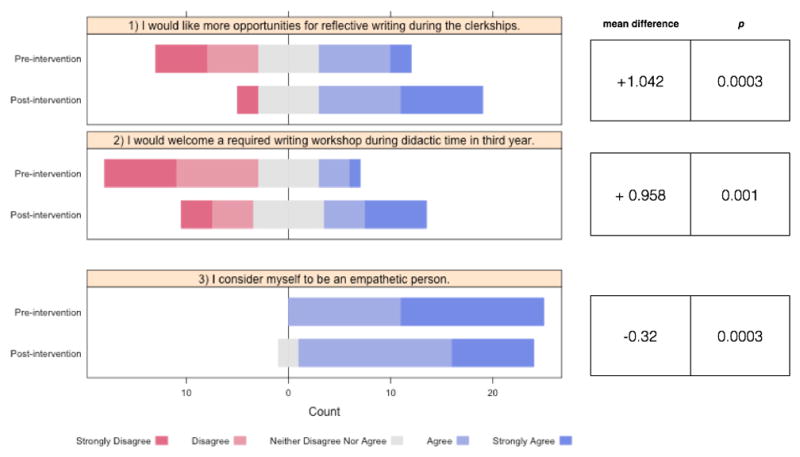

Desire for reflective writing increased after workshop intervention

To assess whether students found the workshop worthwhile, students were surveyed on the following statements:

I would like more opportunities for reflective writing.

I would welcome a required writing workshop during didactic time in the third year.

Increased scores on both questions were assumed to indicate that students found the workshop worthwhile. By contrast, a decreased score on both questions was taken to indicate that students did not find the workshop worthwhile. Responses from 24 subjects were analyzed. Prior to intervention, 32% of subjects agreed with statement 1 and 16% of subjects agreed with statement 2. After intervention, the proportion of subjects agreeing with both statements increased to 64% and 40% respectively. Overall, this increase in agreement after intervention was significant for responses to both statements (p=0.0003 and p=0.001; figure 1-(1&2)).

Figure 1-(1–3).

Student agreement with survey statements, rated on a Likert scale, before and after intervention.

Self-reported empathy decreased after participation in the workshop

Given the previously reported positive relationship between reflective writing and empathy (11), the effect of this writing workshop on empathy was also determined. Given constraints, validated empathy inventories such as the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (14) could not be employed. Instead, empathy was assessed by self-report by measuring agreement with the following statement:

I consider myself to be an empathetic person.

100% of subjects agreed with the statement prior to intervention, with 56% of those endorsing strong agreement. After intervention, the proportion of students reporting strong agreement decreased (32%), and the proportion of students reporting neutrality towards the statement (which was not present in the initial sample) increased to from 0 to 8%. Overall, there was a significant decrease in agreement (p = 0.0003) suggesting that students perceived themselves as less empathetic after the writing workshop (figure 1–3).

Figure 3.

Scatterplot depicting student Likert response to two statements.

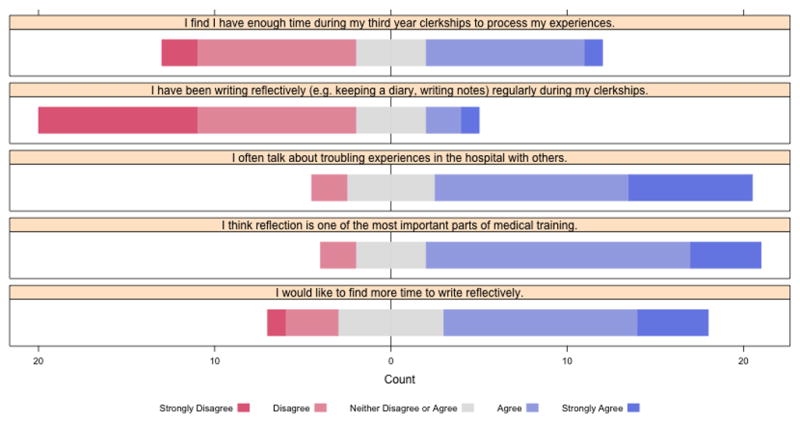

Valuing reflection was correlated with desire for reflective writing

The desire to engage in reflective writing varied considerably prior to participation in the writing workshop (figure 1-(1–2)). We sought to explain this variation by assessing correlation with other subject variables such as writing habits, reflective attitudes and communication behaviors. An inventory of Likert statements was collected targeting each of the above domains (reflection, communication, writing; figure 2). Using Pearson correlation, the associations between this inventory and the statement, “I would welcome a required writing workshop during didactic time in the third year” were examined. Subjects who agreed with the statement “I think reflection is one of the most important aspects of medical training” tended to be more receptive to reflective writing (R = 0.468, p = 0.018; figure 3). Interestingly, other measures assessing writing and communication habits were not significantly correlated with desire for reflective writing (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Inventory of reflection, communication, and writing habits in medical students, rated on a Likert scale, prior to participation in the workshop.

Table 3.

Likert statement correlation with baseline receptivity for a writing workshop.

| Survey Statement | I would welcome a required writing workshop during didactic time in third year. | |

|---|---|---|

| Pearson coefficient | p - value | |

| I consider myself to be an empathetic person. | 0.253 | 0.223 |

| I find I have enough time during my third year clerkships to process my experiences. | −0.273 | 0.187 |

| I have been writing reflectively (e.g. keeping a diary, writing notes) regularly during my clerkships. | 0.077 | 0.714 |

| I often talk about troubling experiences in the hospital with others. | 2.38 | 0.251 |

| I think reflection is one of the most important parts of medical training. | 0.468 | 0.018* |

The workshop improved the perception of the surgical clerkship for some students

As a part of the post-intervention survey, subjects submitted free-form feedback, consisting of responses to two questions (Table 2):

What did you learn from this workshop?

Have your perceptions of the surgical clerkship changed after participation in this workshop?

Responses from 24 participants (1 subject omitted answers to all free-form questions) were analyzed for emerging themes. The results of this analysis are depicted (Table 4). The majority of subjects reported finding ‘new significance in experiences’ (n = 14). Often, this recasting of experiences yielded some insight into their own character, for example:

I tend to lose sight of myself when inundated with new and stressful experiences.

I am someone that carries guilt for a long time.

Table 4.

| Table 4a: Themes derived from free-form response to question: what did you learn about yourself from this workshop? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Theme | Count | Example |

| Found new significance in experiences | 14 | I learned that while I try to process a lot of the thoughts and emotions I have during clerkships on a regular basis, not a whole lot of that reflection is centered around the patient, rather, mostly around me. I think I’d like to improve on that, if I can, now that I’ve realized it. |

| Enjoyed self-reflection | 4 | I enjoy reflection whenever I’m forced to engage in it, but rarely think to make time for it. |

| New connectedness with peers | 3 | Hearing my classmates’ reflections on their experiences on the wards is extremely meaningful to me. |

| Nothing | 3 | |

| Declined to answer | 1 | |

| Table 4b: Themes derived from free-form response to question: did your perceptions of the surgical clerkship change after the workshop? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Theme | Count | Example |

| No | 9 | |

| Gave new perspective | 4 | It did. It illustrated that there is room for personal reflection even in surgery, a clerkship where there isn’t much encouragement to speak about emotions. |

| Reinforced expectation | 4 | It highlighted some of the stereotypical flaws of surgery (less time spent with pt, occasionally putting pts down), which is not exactly new but it was something that was not as salient to me before. |

| Humanized the clerkship | 3 | I helped me to better appreciate the humanity of the surgeons I worked with on the clerkship. |

| Perception more positive | 2 | Helped me draw out positive experiences. |

| Reminded of personal accomplishments | 2 | It helped to highlight the aspects of personal growth and social learning that are a big part of the surgical clerkship rather than just knowledge based learning. |

| Decline to answer | 1 | |

Other themes which emerged included feeling more connected with peers and enjoyment, often unexpectedly, of self-reflection.

In response to the question of whether the workshop changed the perception of the surgical clerkship, the largest group reported no change in perception (43%, figure 4). However, a considerable minority (39%) of students reported a more positive perception following the workshop. This positive response was reducible to four categories: the workshop (1) humanized the clerkship, (2) gave new perspective, (3) was more positive than anticipated or (4) reminded students of their personal accomplishments. The remaining students (17%) who reported more negative perceptions of surgery after the workshop wrote that the workshop reminded them of experiences which reinforced negative stereotypes about the surgical specialty.

Figure 4.

Distribution of student response to the question “did the workshop change your perception of the surgical clerkship?”

Discussion

Reflective writing has emerged as a tool to foster empathy and insight in medical trainees (8, 15). However, there have been no formal studies, to our knowledge, examining the role for reflective writing in a surgical setting. In this proof-of-concept study, we analyzed medical student response to a novel reflective writing workshop during the surgical clerkship. The results of this study indicate that the workshop was generally well-received by students. Specifically, student desire for reflective writing and student receptivity to a required writing workshop increased significantly after participation. Furthermore, the majority of students (88%) surveyed report having had some insight as a result of this workshop.

In addition to having been well-received by students, the workshop may also have improved student perception of the surgical profession. After participation in the workshop, a proportion of students (39%) reported a more positive perception of surgery, including that the workshop helped to humanize the surgeons with whom they had worked, as well as reminded them of their own accomplishments. This finding raises the possibility that this workshop may assist in bolstering recruitment to surgical specialties. For example, surgical culture is often perceived, correctly or otherwise, as malignant. In one survey of medical students, the majority of graduating seniors found surgeons to be pessimistic and cynical (16). Another report found that students often feel alienated by surgical personalities (17). These negative perceptions are problematic for recruitment to the surgical specialty, especially given that personality fit is the most important factor for students when deciding on their specialty (18). Participation in this writing workshop may help improve perceived personality fit among students valuing reflection, as reflected in this student comment:

[This workshop] illustrated that there is room for personal reflection even in surgery, a clerkship where there isn’t much encouragement to speak about emotions.

One limitation of our study was the high attrition rate. 44% of those that completed the first survey did not complete the second, raising the possibility of a sampling bias in our data. In particular, it is plausible that only the students who enjoyed the workshop completed both surveys, artificially inflating the positive response that was observed. However, if this scenario were true, one would expect student attitudes towards reflective writing to skew positive in the post-intervention survey, which they did not. In fact, in the post-intervention survey, student agreement with the statement “I would welcome a required reflective writing workshop” (figure 1–2) was nearly normally distributed. While selection bias is nevertheless a theoretical possibility, we do not believe it significantly impacted our conclusions.

Two secondary findings merit further discussion. The first finding is that students were, at baseline, not receptive to reflective writing. Prior to participation in the workshop, only 16% of respondents agreed with the statement ‘I would welcome a required writing workshop’ (figure 1–2). This negative attitude among medical students towards reflective writing is well-documented (19–21), with various explanations for why medical students resist reflective writing having been put forward (21). The most plausible explanations include: 1) reflection’s perceived lack of importance relative to hard skills (e.g. clinical reasoning, procedural skills) 2) the sentiment that teaching reflection is patronizing, since most medical students feel they are already competent in this arena. In this study, we find evidence to support the first explanation. Specifically, prior to intervention, students who were unreceptive to reflective writing also tended to disagree that reflection was an important value in medical training. Further investigation into the reasons for reflection’s perceived lack of importance may be helpful for improving medical student engagement in a reflective writing skills curriculum.

The second finding is that self-reported empathy decreased after participation in the workshop. This finding contradicts the literature, which finds that empathy increases after reflective writing interventions (11). One reason for the discrepancy lies in the differing outcome measures. In our study, we measured student subjective self-perception (students reported how much they agreed with the statement “I consider myself to be an empathetic person”). By contrast, studies which use formal empathy scales, such as the 20-point Jefferson Scale of Empathy, attempt to measure a student’s objective level of empathy by probing the student’s beliefs and values (e.g. gauging student belief in the importance of emotions in the patient encounter, comfort with perspective-taking) (22). Follow-up studies examining the effect of this writing workshop on a formal (i.e. objective) empathy inventory would be worthwhile, since it is the formal empathy score which has been correlated with improved patient outcomes (6, 7). Nonetheless, why subjective self-perception of empathy deflates after participation in the workshop remains an interesting question. One possibility is that after having observed peers reflect on their empathetic interactions with patients, students rate their own empathy lower. This deflation of self-perception may not necessarily be detrimental. For one, a deflated self-perception may challenge students to improve their behaviors and habits.

Given that this was a proof-of-concept study, further investigations will be necessary to validate this intervention. As mentioned above, it will be worthwhile to investigate the effects of this workshop on a formal empathy inventory, as well as closer dissection of those students in particular resistant to the idea of reflection: is it because they feel that they are already competent in this arena or is it because they don’t value reflection as compared with other domains? In addition to these studies, further investigation into the differential effect on presurgical vs. non-presurgical trainees would be valuable. Since this workshop is intended primarily as prophylaxis against empathy attrition in pre-surgical trainees, it is important to establish that pre-surgical trainees, in particular, see benefits.

Given the promising results of this study, this workshop has become a permanent session in the Yale school of Medicine’s surgical clerkship didactic curriculum. Now in it’s second year, there is a cadre of student facilitators who are able to facilitate such workshops, with the hopes of continuing these sessions as long as student continue to benefit from them.

Conclusion

In summary, this reflective writing workshop improves attitudes towards reflective writing and the surgical profession. These findings suggest that this workshop may bolster student insight and recruitment to surgical specialties. Larger studies that examine objective measures of empathy will help determine whether empathy is improved after participation in this workshop.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Anna Reisman, M. D. for her assistance with incorporating these workshops into Yale School of Medicine’s curriculum.

Footnotes

ACGME competencies addressed: 1) Patient Care 2) Professionalism 3) Interpersonal Communication 4) Practice-based learning

This work has not been presented at any meetings as of time of submission. There are no financial relationships, conflicts of interest or sources of support to disclose.

Bibliography

- 1.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, et al. Physician empathy: Definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1563–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnsley J, Williams AP, Cockerill R, Tanner J. Physician characteristics and the physician-patient relationship: Impact of sex, year of graduation, and specialty. Canadian Family Physician. 1999;45:935–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009;84:1182–91. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Evaluation & the health professions. 2004;27:237–51. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamothe M, Boujut E, Zenasni F, Sultan S. To be or not to be empathic: the combined role of empathic concern and perspective taking in understanding burnout in general practice. BMC family practice. 2014;15:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, et al. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2011 Mar;86(3):359–64. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canale SD, Louis DZ, Maio V, et al. The Relationship Between Physician Empathy and Disease Complications. Academic Medicine. 2012:1243–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2004;79:351–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branch W, Pels RJ, Lawrence RS, Arky R. Becoming a doctor. Critical-incident reports from third-year medical students. The New England journal of medicine. 1993 Oct 7;329(15):1130–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310073291518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong FK, Kember D, Chung LY, Yan L. Assessing the level of student reflection from reflective journals. Journal of advanced nursing. 1995;22:48–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22010048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen I, Forbes C. Reflective writing and its impact on empathy in medical education : systematic review. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions. 2014;6:1–6. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2014.11.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamieson S. Likert scales: How to (ab)use them. Medical Education. 2004;38:1217–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norman G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2010;15:625–32. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen DCR, Kirshenbaum DS, Yan J, et al. Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school. Medical teacher. 2012;34:305–11. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.644600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro J, Rucker L, Boker J, Lie D. Point-of-view writing: A method for increasing medical students’ empathy, identification and expression of emotion, and insight. Education for Health: Change in Learning and Practice. 2006;19:96–105. doi: 10.1080/13576280500534776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naylor Ra, Reisch JS, Valentine RJ. Do Student Perceptions of Surgeons Change during Medical School? A Longitudinal Analysis during a 4-Year Curriculum. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2010;210:527–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barshes NR, Vavra AK, Miller A, et al. General surgery as a career: A contemporary review of factors central to medical student specialty choice. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2004;199:792–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.05.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cochran A, Melby S, Neumayer La. An Internet-based survey of factors influencing medical student selection of a general surgery career. American Journal of Surgery. 2005;189:742–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rees C, Rees C, Sheard C, Sheard C. Undergraduate medical students’ views about a reflective portfolio assessment of their communication skills learning. Medical Education. 2004;38:125–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross S, Maclachlan A, Cleland J. Students’ attitudes towards the introduction of a Personal and Professional Development portfolio: potential barriers and facilitators. BMC medical education. 2009;9:69. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song P, Stewart R. Reflective writing in medical education. Medical teacher. 2012:1–2. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.716552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001:349–65. [Google Scholar]