Abstract

Background

Toxicity can lead to nonpersistence with adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET). We hypothesized that ET-induced change in grip strength would predict for early discontinuation of therapy because of musculoskeletal toxicity, and would be associated with BMI.

Patients and Methods

Postmenopausal women with breast cancer starting a new adjuvant ET were enrolled. Patients were monitored for 12 months to assess symptoms and ET adherence as well as change in grip strength and body mass index (BMI). The association between the change in grip strength and time to discontinuation was assessed using a joint longitudinal and survival model.

Results

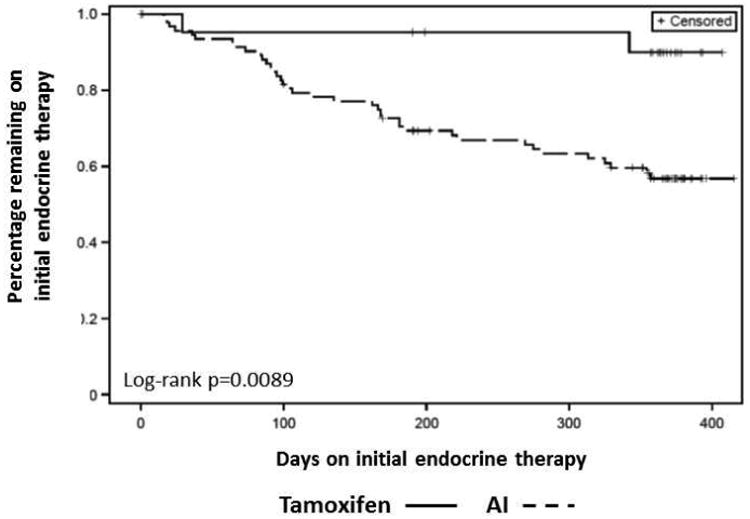

40.9% of 93 AI-treated and 9% of 22 tamoxifen-treated patients discontinued ET within 12 months because of toxicity (p=0.019). There was a trend towards a greater decrease in grip strength in AI-treated patients over time (p=0.055), which was not significantly associated with time to discontinuation (p=0.96). Receipt of an AI (HR 5.49, p= 0.019) and baseline pain (HR 1.19, p=0.004) significantly decreased the time to discontinuation.

Conclusion

In contrast with prior reports, change in grip strength was not associated with time to discontinuation of AI therapy. Future research should focus on proactive management of patients at increased risk of AI intolerance, such as those with high levels of pre-existing pain.

Keywords: breast cancer, anthropomorphic, nonpersistence, aromatase inhibitor, pain

Introduction

Adjuvant aromatase inhibitors (AI) and tamoxifen reduce recurrence and mortality in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.1 The three third-generation AIs in routine clinical use, including two nonsteroidal compounds (anastrozole and letrozole) and a steroidal compound (exemestane), have similar benefit and toxicity profiles based on direct and cross-trial comparisons.2

Despite the excellent disease outcomes with anti-endocrine therapy, up to 20% of patients are non-persistent with AI therapy, due primarily to toxicity of treatment.3, 4 AI-associated toxicity, which is primarily musculoskeletal in nature, negatively impacts the quality of life of breast cancer survivors,5 and can result in worse breast cancer outcomes.4, 6 Despite considerable research, the mechanism that underlies this AI-associated musculoskeletal syndrome (AIMSS) remains unknown. In addition, only a few predictors of developing toxicity have been identified, including prior treatment with chemotherapy, shorter time since menopause, and possibly obesity.3, 7-9

Tenosynovitis at the wrist and loss of grip strength following initiation of AI therapy was identified in a small cohort of AI-treated patients.10 Subsequently, associations between loss of grip strength and both musculoskeletal symptoms and extremes of body-mass index (BMI) were noted in AI-treated patients that were not evident in tamoxifen-treated patients.11, 12

We conducted a prospective observational study of postmenopausal women starting adjuvant endocrine therapy in order to validate these findings in a patient population with a higher proportion of obese patients. We hypothesized that patients with decreased grip strength during AI therapy would be more likely to discontinue treatment, and would be more likely to have either low or high BMI. We also examined the patient-reported symptom experience of patients treated with AIs versus tamoxifen, as well as endocrine therapy treatment patterns of patients who discontinued initially prescribed AI therapy because of toxicity.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were recruited at a single institution (University of Michigan) from September 2009 through July 2013 (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT01223833). Postmenopausal women with stage 0-III breast cancer who were planning to receive adjuvant endocrine therapy with tamoxifen (Novaldex) or a third-generation aromatase inhibitor (anastozole, exemestane, letrozole) were eligible. Choice of endocrine therapy was at the discretion of the patient and the treating provider. All surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy were completed prior to initiation of adjuvant endocrine therapy. Prior tamoxifen and AI therapy were permitted, although patients were required to discontinue the medication at least 4 weeks prior to enrollment. No enrolled patients had previously taken AI therapy. Patients were ineligible if they had a pre-existing major rheumatologic disorder or concomitant use of sex hormone-containing medications or luteinizing hormone receptor hormone agonist therapy. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, and all patients provided written informed consent prior to participation in any protocol-directed procedures.

Study Design

After enrollment all patients underwent baseline assessment prior to initiation of adjuvant endocrine therapy. The assessments included measurement of height, weight, hip and waist circumference, bilateral grip strength, questionnaires, and phlebotomy. Choice of endocrine therapy was at the discretion of the treating physician. Each assessment was repeated 3, 6, and 12 months following initiation of adjuvant endocrine therapy. If a patient changed from one AI to another during study participation, assessments were continued and timing was based on the original treatment start date.

Grip strength was measured using a modified sphygmomanometer (Martin Vigorimeter Measuring Instrument, Albert Waeschle Ltd, Dorset, UK). Patients squeezed the balloon of the instrument 3 times with each hand, and the maximal force from each of the 6 assessments was recorded. The maximum value for either the right or left hand at each time point was used.

At each time point patients rated their average pain over the past 7 days using an 11-point Likert scale. At months 3, 6, and 12 patients also completed a questionnaire to more comprehensively assess the musculoskeletal and menopausal symptoms experienced by patients, as well as their perception of the association between the symptoms and the endocrine therapy using a 5-point Likert scale (from “definitely not due to medication” to “definitely due to medication”). Adherence to therapy was also assessed using the MARS-5 questionnaire.13

Statistical methods

For continuous data, including grip strength, BMI, waist to hip ratio, and baseline demographics, between-group differences were assessed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Between-group differences for categorical variables were determined using chi-square or Fisher's exact tests. Spearman correlation assessed the association between right and left hand maximum grip strength, as well as baseline maximum grip strength and baseline values for BMI and waist to hip ratio. The Kaplan Meier method and log-rank test were used to compare the time to discontinuation of endocrine therapy (defined as the earlier of treatment discontinuation or end of the study at one year) between AI- and tamoxifen-treated patients. Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate associations between the time to discontinuation of ET therapy, and baseline anthropometric factors controlling for the type of endocrine therapy treatment.

The primary endpoint was the effect of BMI on grip strength after 12 months of therapy based on preliminary data.12 However, no effect of BMI or its quadratic term was identified when added to a multivariable model in the primary analysis. Therefore, the association between change in grip strength, baseline BMI and the time to discontinuation of first therapy was instead examined using a joint longitudinal and survival model that accounted for missing data. The association between change in grip strength and development of new or worsening musculoskeletal symptoms (defined as arthralgias or myalgias) was assessed using a generalized linear model (GEE estimation). The presence of patient-reported symptoms was compared between treatment groups using chi-square or Fisher's exact tests. For all p-values reported, no correction for multiple testing was applied.

Results

Patients

Of the 115 patients enrolled in the trial, 93 initiated therapy with an AI and 22 initiated tamoxifen (Table 1). Of those who started AI therapy, 76 (81.7%) received anastrozole, 16 (17.2%) received letrozole, and one (1.1%) received exemestane. Median age of all patients was 62 years (range 41-79). Average body mass index (BMI) was 30.1 (SD 7.1); 42% of AI-treated patients had a BMI of 30 or greater. Sixty-four percent of patients reported muscle or joint pain in the three months prior to enrollment. Average muscle and joint pain for all patients in the week prior to enrollment was 2.3 (SD 2.1) on an 11 point scale. In this postmenopausal population, all baseline patient characteristics were well-balanced between the two groups with the exception that more AI-treated patients had received adjuvant chemotherapy (p=0.004) and more tamoxifen-treated patients had a history of thyroid abnormalities (p=0.005).

Table 1. Baseline demographic and medical characteristics.

| Characteristic | Total (n=115) | AI (n=93) | Tamoxifen (n=22) | P value# |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, years; median (range) | 62 (41-79) | 62 (41-79) | 62 (44-69) | 0.41 |

|

| ||||

| BMI, kg/m2; mean (SD) | 30.1 (7.1) | 30.4 (7.1) | 29.0 (7.0) | 0.40 |

|

| ||||

| WHR; mean (SD) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.49 |

|

| ||||

| Maximum grip strength, kPa; mean (SD) | ||||

| - right hand | 57.3 (11.5) | 57.5 (11.7) | 56.4 (10.9) | 0.83 |

| - left hand | 54.6 (10.8) | 54.8 (10.9) | 53.7 (10.7) | 0.76 |

|

| ||||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy; n (%) | ||||

| - Yes, any | 54 (47.0) | 50 (53.8) | 4 (18.2) | 0.004 |

| - Taxane-based | 50 (43.5) | 46 (49.5) | 4 (18.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Adjuvant radiotherapy; n (%) | 85 (73.9) | 72 (77) | 13 (59) | 0.10 |

|

| ||||

| Prior tamoxifen; n (%) | 9 (9.7) | 9 (9.7) | N/A | N/A |

|

| ||||

| Average musculoskeletal pain (0-10); mean (SD) | 2.3 (2.1) | 2.3 (2.1) | 2.4 (1.9) | 0.72 |

|

| ||||

| Initial therapy | N/A | |||

| - Anastrozole | 76 (66.1) | 76 (81.7) | ||

| - Exemestane | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| - Letrozole | 16 (13.9) | 16 (17.2) | ||

| - Tamoxifen | 22 (19.1) | 22 (100) | ||

|

| ||||

| Comorbidities (self-reported) | ||||

| - Osteoarthritis | 57 (50.4) | 44 (47.8) | 13 (61.9) | 0.24 |

| - Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (4.8) | 0.34 |

| - Carpal tunnel syndrome | 25 (21.7) | 20 (21.5) | 5 (22.7) | 1.0 |

| - Tendinitis | 17 (14.8) | 13 (14.0) | 4 (18.2) | 0.74 |

| - Rotator cuff injury | 24 (21.4) | 20 (22.2) | 4 (18.2) | 0.78 |

| - Plantar fasciitis | 27 (24.1) | 22 (24.4) | 5 (22.7) | 1.0 |

| - Diabetes mellitus | 16 (13.9) | 13 (14.0) | 3 (13.6) | 1.0 |

| - Stroke | 4 (3.5) | 4 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| - Hypertension | 47 (40.9) | 38 (40.9) | 9 (40.9) | 1.0 |

| - Thyroid abnormalities | 34 (30.1) | 22 (24.2) | 12 (54.5) | 0.005 |

p-value denotes statistically significant difference between those on an AI versus those on tamoxifen; calculated using Wilcoxon rank sum, chi-square or Fisher's exact tests

At baseline, grip strength in the right and left hands were strongly correlated (Spearman correlation, r=0.79, p<0.001). No correlations between baseline maximum grip strength and either BMI (r=0.01, p=0.94) or waist/hip ratio (r=-0.15, p=0.10) at baseline were identified.

Adherence and Persistence with endocrine therapy

Adherence was assessed using the MARS-5 questionnaire. Two-thirds of patients (66/99) reported always taking the medication as prescribed at all assessed timepoints. Of those who reported not always taking it as prescribed 78.8% (26/33) reported forgetting to take the medication rarely or sometimes, 15.2% (5/33) reported intentionally missing a dose rarely, and 4 patients either stopped taking the medication for a while or altered the dose. Rates of nonadherence were similar between AI and tamoxifen treated patients (36% vs 32%, respectively).

After 1 year of study participation, 65.2% (75/115) of patients reported still taking the initially prescribed endocrine therapy. Of the 93 patients treated with an AI, 38 (40.9%) discontinued the initial AI medication during the first year, whereas of the 22 patients treated with tamoxifen, 2 (9.0%) stopped taking it (p=0.019) (Supplemental Figure 1). Seventy-three percent of AI-treated patients who discontinued their initial therapy reported doing so at least in part because of arthralgia or other musculoskeletal symptoms.

Of the 38 patients who discontinued initial AI medication within the first year of therapy, 31 (82%) initiated treatment with a second AI, 4 started tamoxifen, and 3 opted for no endocrine therapy (Supplemental Figure 1A). One tamoxifen-treated patient switched to AI therapy, and the other discontinued endocrine therapy entirely (Supplemental Figure 1B). Eighteen (51%) patients discontinued treatment from the second endocrine therapy within the first year of therapy; 76% reported musculoskeletal symptoms as one of the reasons for discontinuation.

Associations between baseline factors and time to AI discontinuation

AI-treated patients had a significantly increased risk of discontinuing their initial treatment than tamoxifen-treated patients (HR 5.49, 95% CI 1.32-22.80, p=0.019, Figure 1). Controlling for the difference between treatment types, only higher baseline pain was significantly associated with a higher risk of discontinuing therapy (HR 1.19, 95% CI 1.06-1.35, p=0.004) (Table 2). Neither age nor prior taxane chemotherapy was associated with time to AI discontinuation.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier plot of treatment discontinuation by initial adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Tamoxifen is indicated by the solid line, and aromatase inhibitors (AI) are indicated by the dashed line.

Table 2. Associations between discontinuation of AI therapy during the first year of therapy and baseline anthropometric factors; CI confidence interval.

| Baseline condition | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum grip strength (5 mmHg) | 0.96 | 0.87 | 1.14 | 0.94 |

| BMI | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.03 | 0.42 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.26 | 0.008 | 8.6 | 0.45 |

| Use of prior taxane chemotherapy | 0.80 | 0.42 | 1.50 | 0.48 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.56 |

| Self-reported pain | 1.19 | 1.06 | 1.35 | 0.004 |

P-value from Cox Proportional Hazards Models controlling for treatment

Association of grip strength, BMI and time to discontinuation of initial endocrine therapy

Average maximum grip strength gradually decreased between baseline and 12 months for those with measurements treated with AI but not in tamoxifen-treated patients (Table 3). Baseline BMI was not associated with the change in grip strength (p=0.88). Although there was a borderline significant difference in the change in grip strength over the study between those on tamoxifen versus those on AI (p=0.055) such that grip strength decreased more over time for those on AI therapy, the change in grip strength over the study period was not significantly associated with time to discontinuation of first therapy (p=0.96) or with new or worsened musculoskeletal symptoms (p=0.87).

Table 3.

Change in maximum grip strength from baseline over time, by endocrine therapy.

| Aromatase Inhibitor (n=93) | Tamoxifen (n=22) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) |

| 3 | 88 | -1.5 (11.9) | 19 | -0.6 (8.9) |

| 6 | 81 | -3.6 (13.9) | 19 | -0.8 (10.9) |

| 12 | 70 | -7.0 (15.9) | 19 | 0.6 (10.2) |

SD: standard deviation.

Patient-reported symptoms on endocrine therapy

More than 80% of patients reported pain during treatment with either AI or tamoxifen, with similar rates for all sites of pain reported for the two classes of medication (Supplemental Table S1-S3). However, a higher proportion of patients reported that their aches and pains were probably or definitely related to the AI medication compared to tamoxifen (53.5% vs 13.3%, p=0.005). Similar findings were noted for joint stiffness, but not for myalgias or carpal tunnel syndrome. In contrast to the similar incidence of pain between the two cohorts, more patients reported new or worsening numbness during AI therapy compared to tamoxifen (39.5% vs 15%, p=0.041).

Of the other assessed symptoms, only the incidence of vaginal discharge was different between the two cohorts, with a higher rate in tamoxifen-treated patients (35% vs 8%, p=0.004), although the attribution to drug was similar between the two medications. Although the incidence of hot flashes was similar between the two cohorts, more patients attributed hot flashes to taking tamoxifen than to AI therapy (100% vs 72.6%, p=0.017).

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed the high rate of initial endocrine therapy discontinuation due to toxicity in postmenopausal women treated with AI therapy. Poor adherence and non-persistence with treatment have implications for breast cancer outcomes, since both have been shown to be associated with increased breast cancer mortality.4, 6 However, no reliable predictors of intolerance have yet been identified. We confirmed that baseline pain is a predictor of treatment discontinuation. However, we were unable to confirm our hypothesis that those patients who experienced more loss of grip strength during therapy would be more likely to discontinue treatment early. In addition, neither baseline grip strength nor BMI were predictive of treatment discontinuation. Therefore, use of either baseline grip strength or change in grip strength during treatment cannot be used to predict which patients are likely to have poor tolerance of AI therapy.

This study was performed to validate a prior report that decreased grip strength and discontinuation of AI therapy because of AIMSS were associated with extremes of BMI.12 However, although we identified a borderline significant decrease in grip strength in AI-treated patients compared to tamoxifen-treated patients, we were unable to validate the previously reported association with BMI. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, although one potential explanation is differences in BMI distribution among enrolled patients in the two studies. In the prior study the average BMI was 26 and the maximum BMI was 41, whereas in this report the average was more than 30 and the maximum was 50. An additional possible reason for the discrepancy is differences in clinical practice. Since the endpoint was discontinuation of therapy due to toxicity, providers at one institution may be more likely to recommend treatment discontinuation compared to another, which would influence the findings. Only 15% of patients in the original University of Leuven study discontinued AI therapy, in contrast with 40% in the current report of patients treated at the University of Michigan. This decrease in medication persistence could result in dilution of the perceived effect on discontinuation by BMI if patients with less severe symptoms discontinued therapy.

In this study of a postmenopausal cohort of women with early stage breast cancer we demonstrated a statistically significant greater rate of early discontinuation of AI therapy compared to tamoxifen. However, it is important to consider that this observational study was not randomized, and there were presumably reasons such as co-morbidities that one drug was chosen over the other as initial therapy. Importantly, previously identified potential predictors of developing musculoskeletal toxicity, including median age, average BMI, and average pain at the time of treatment initiation, were similar between the two groups. This finding suggests that aromatase inhibition causes more bothersome toxicities than does treatment with tamoxifen.

Interestingly, discontinuation of AI therapy continued throughout the study period and did not plateau. This is similar to other previously reported trials of AI therapy including the Arimidex Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination Trial, which demonstrated a continued increase in discontinuation throughout the 5 years of therapy, especially in the first year.9 However, it remains unclear whether the symptoms that develop early in the treatment course have a different etiology compared with those that become bothersome later, and whether alternative management approaches are required.

Efforts to improve tolerance of and persistence with AI therapy is critical to optimizing breast cancer outcomes. This is particularly important in light of the newer data supporting extended adjuvant endocrine therapy, as well as the superiority of AI therapy in combination with ovarian suppression or ablation for premenopausal women at high risk of breast cancer recurrence.14, 15 As studies have previously reported,3, 16 we demonstrated that some patients who are unable to tolerate the first AI medication switched to a second AI medication and a minority were able to persist with the second therapy. This suggests that one potential option for patient management could be intermittent discontinuation of therapy, although the implications of this approach on risk of disease recurrence are unknown. In addition, more than half subsequently discontinued the second AI as well because of toxicity, so this strategy is not likely to be successful for the majority of patients.

Reducing the toxicity of AI therapy has been challenging. The only randomized interventions that have demonstrated improvement are acupuncture and exercise, both of which resulted in moderate improvements in symptoms.17, 18 In addition, we have reported encouraging phase II results with duloxetine. This observation is currently being tested in a phase III randomized clinical trial (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01598298).19 However, the majority of interventions tested are implemented at the time a patient reports treatment-emergent symptoms. It is unknown whether upfront management of pre-existing symptoms in this population with a high prevalence of baseline musculoskeletal symptoms may result in better long-term tolerance of therapy. Efforts to use educational interventions to improve adherence have been tested, but thus far have been unsuccessful.20-22 More research is needed to identify effective prevention and management strategies for this vexing toxicity.

Conclusion

Persistence with adjuvant endocrine therapy continues to be less than optimal. Identification of both predictors of and mechanisms underlying development of toxicity is important for the design of preventative approaches. Based on these findings, neither assessment of grip strength nor BMI appears to be a useful surrogate for increased risk of developing bothersome AI toxicity. However, in this study we confirmed that pre-existing pain at AI initiation is associated with increased risk of treatment discontinuation, and should be a focus of future management approaches. Lessening toxicity will lead to increased persistence with therapy, which in turn may lead to improved breast cancer outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Practice Points.

Musculoskeletal pain is prevalent in postmenopausal women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant endocrine therapy

Non-persistence with AI therapy because of toxicity is common

This study demonstrated that patients with pre-existing pain may be at increased risk for intolerance of AI therapy

Future research should focus on pro-active management of patients at high risk of nonpersistence

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation [grant number CI-53-10]; the National Institutes of Health [grant number 5T32-CA083654]; and the Fashion Footwear Association of New York/QVC Shoes on Sale. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burstein HJ, Prestrud AA, Seidenfeld J, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline: update on adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3784–3796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Ingle J, et al. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:509–518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry NL, Azzouz F, Desta Z, et al. Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation due to treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:936–942. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chirgwin JH, Giobbie-Hurder A, Coates AS, et al. Treatment adherence and its impact on disease-free survival in the Breast International Group 1-98 trial of tamoxifen and letrozole, alone and in sequence. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2452–2459. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.8619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadakia KC, Snyder CF, Kidwell KM, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and early discontinuation in aromatase inhibitor-treated postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21:539–546. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:529–537. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crew KD, Greenlee H, Capodice J, et al. Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3877–3883. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao JJ, Stricker C, Bruner D, et al. Patterns and risk factors associated with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:3631–3639. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sestak I, Cuzick J, Sapunar F, et al. Risk factors for joint symptoms in patients enrolled in the ATAC trial: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:866–872. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morales L, Pans S, Verschueren K, et al. Prospective Study to Assess Short-Term Intra-Articular and Tenosynovial Changes in the Aromatase Inhibitor-Associated Arthralgia Syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3147–3152. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lintermans A, Van Calster B, Van Hoydonck M, et al. Aromatase inhibitor-induced loss of grip strength is body mass index dependent: hypothesis-generating findings for its pathogenesis. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1763–1769. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lintermans A, Van Asten K, Wildiers H, et al. A prospective assessment of musculoskeletal toxicity and loss of grip strength in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen, and relation with BMI. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:109–116. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2986-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horne R. The medication adherence report scale. Brighton, UK: University of Brighton; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burstein HJ, Temin S, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2255–2269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burstein HJ, Lacchetti C, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update on ovarian suppression. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1689–1701. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.9573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briot K, Tubiana-Hulin M, Bastit L, Kloos I, Roux C. Effect of a switch of aromatase inhibitors on musculoskeletal symptoms in postmenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer: the ATOLL (articular tolerance of letrozole) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0692-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crew KD, Capodice JL, Greenlee H, et al. Randomized, blinded, sham-controlled trial of acupuncture for the management of aromatase inhibitor-associated joint symptoms in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1154–1160. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irwin ML, Cartmel B, Gross CP, et al. Randomized exercise trial of aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1104–1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry NL, Banerjee M, Wicha M, et al. Pilot study of duloxetine for treatment of aromatase inhibitor-associated musculoskeletal symptoms. Cancer. 2011;117:5469–5475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neven P, Markopoulos C, Tanner MME, et al. The impact of educational materials on compliance and persistence with adjuvant aromatase inhibitors: 2 year follow-up and final results from the CARIATIDE study. Cancer Res, abstract P5-16-02. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadji P, Blettner M, Harbeck N, et al. The Patient's Anastrozole Compliance to Therapy (PACT) Program: a randomized, in-practice study on the impact of a standardized information program on persistence and compliance to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1505–1512. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu KD, Zhou Y, Liu GY, et al. A prospective, multicenter, controlled, observational study to evaluate the efficacy of a patient support program in improving patients' persistence to adjuvant aromatase inhibitor medication for postmenopausal, early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.