Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived CD11b+CD14+ monocytes in a murine model of chronic liver damage.

METHODS

Chronic liver damage was induced in C57BL/6 mice by administration of carbon tetrachloride and ethanol for 6 mo. Bone marrow-derived monocytes isolated by immunomagnetic separation were used for therapy. The cell transplantation effects were evaluated by morphometry, biochemical assessment, immunohistochemistry and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

RESULTS

CD11b+CD14+ monocyte therapy significantly reduced liver fibrosis and increased hepatic glutathione levels. Levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1β, in addition to pro-fibrotic factors, such as IL-13, transforming growth factor-β1 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 also decreased, while IL-10 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 increased in the monocyte-treated group. CD11b+CD14+ monocyte transplantation caused significant changes in the hepatic expression of α-smooth muscle actin and osteopontin.

CONCLUSION

Monocyte therapy is capable of bringing about improvement of liver fibrosis by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, as well as increasing anti-fibrogenic factors.

Keywords: Monocytes, Bone marrow mononuclear cells, Cell therapy, Macrophages, Glutathione, Liver fibrosis

Core tip: Chronic inflammation is now recognized as a central player in the development of liver fibrosis. Studies have shown that activated macrophages establish a link between chronic inflammation and fibrosis in various organs. The present study evaluated the therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived CD11b+CD14+ monocytes in a murine model of liver damage. The results show that mice with transplants had improvement of liver fibrosis by way of a reduction in oxidative stress and inflammation and an increase in anti-fibrogenic factors. The study demonstrates the beneficial effects of cellular therapy in liver fibrosis and also reports on the important modulatory mechanisms involved.

INTRODUCTION

Abuse of alcohol, infections caused by hepatitis viruses B and C, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are the main causes of liver tissue damage[1]. These risk factors can lead to focal or diffuse hepatocellular degeneration and necrosis. Persistent inflammatory stimulus in the liver can induce the formation of fibrous tissue, and ultimately lead to the development of liver cirrhosis[2]. Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) play an important role in liver fibrogenesis because they are the main source of secreted extracellular matrix (ECM) components[3]. When severe liver damage occurs, HSCs are activated, mainly by the action of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by damaged hepatocytes or liver-resident macrophages[4].

The ECM components comprise various types of proteins, including osteopontin (OPN)[5], a pro-inflammatory cytokine that modulates the pro-fibrogenic phenotype of HSCs and is involved in many physiological and pathological processes, including inflammation, fibrosis and angiogenesis[5,6]. OPN has also been described as a mediator induced by the Hedgehog pathway and plays an important role in the repair of acute and chronic liver damage, both in humans and experimental models[7,8].

The remodeling of fibrous tissue is a complex mechanism by which multiple cell types, capable of producing molecules such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), play an important role in the synthesis and degradation of the ECM[9]. In chronic liver damage, the establishment of hepatic fibrosis is directly related to MMP/TIMP imbalance[10], thereby showing that MMPs and TIMPs may be potent therapeutic targets[11].

Although important advances in the knowledge of chronic liver diseases have been made, the existing treatments are still limited. New, more effective and less invasive therapeutic strategies are therefore needed. In this context, several studies of regenerative medicine have demonstrated the potential of cell therapy as a promising emerging treatment for liver diseases[12] and various cell populations have been investigated to this end[12,13]. Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs) have shown promising results in both experimental[14] and clinical[15,16] studies. Previous studies of experimental models of liver injury have demonstrated that cell therapy is able to decrease mortality[17] and levels of hepatic fibrosis[14], improve biochemical parameters[18], increase MMP-9 expression[19], and reduce levels of TGF-β1[20] and galectin-3 expression[14].

Identifying which components of the BMMC population are responsible for the beneficial effects of cell therapy is extremely important for clinical application. Recent studies have reported that monocytes may have important therapeutic potential in chronic liver diseases[21,22]. These cells are the precursors of the heterogeneous macrophage population involved in liver repair responses. In the liver, macrophages perform various functions, such as phagocytosis and cytokine production, which are important in the inflammatory response to damage, liver fibrosis and degradation of ECM[23,24]. In vitro assays have shown that monocytes maintained in culture supplemented with hepatocyte growth factor exhibited similar behavior to those hepatic cells obtained from the liver culture[21]. One preclinical study has shown that cellular therapy with cultured macrophages decreases murine liver fibrosis and this is followed by changes in the levels of some mediators involved in liver repair[22].

Although these findings are of great importance, information about the functions of monocyte/macrophage cell lineages in cell therapy for liver diseases is still limited. The present study evaluated the therapeutic potential of bone marrow-derived monocytes in a murine model of chronic liver damage induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and ethanol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (4-6 wk of age), weighing 20-23 g were obtained from the Animal Breeding Center Laboratory Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), and housed in the animal research facility in the Aggeu Magalhães Research Center (CPqAM; FIOCRUZ, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil). The animal protocol was designed to minimize pain or discomfort to the animals, which were maintained in rooms with a controlled temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and humidity (55% ± 10%) environment under continuous air renovation conditions. Animals were housed in a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle and free access to food (Nuvilab, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil) and water. Experimental procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation and approved by the Ethics Committee for the Certified Use of Animals (CEUA-CPqAM 15/2011).

Chronic liver damage and experimental design

Chronic liver damage was induced in the mice by orogastric administration of 200 μL of 20% CCl4 solution diluted in olive oil, in twice weekly doses[14]. The mice also received a 5% ethanol solution in water ad libitum. CCl4 treatment was carried out for 6 mo. The mice were randomly divided into four experimental groups with chronic hepatic damage: Group I: Control mice (normal mice) (n = 5); Group II: Saline-treated mice (n = 5); Group III: Mice treated with BMMCs (n = 5); Group IV: Mice treated with BMMC-derived monocytes (n = 5).

Isolation of BMMCs and monocytes

Bone marrow was harvested from the femurs and tibiae of donor C57BL/6 mice (n = 15) and BMMCs were purified by centrifugation in a Ficoll gradient (Histopaque 1119 and 1077; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States) at 1000 × g for 15 min. This protocol facilitates the rapid recovery of viable BMMCs using two ready-to-use separation mediums in conjunction. The BMMC preparation was used to isolate monocytes by way of the immunomagnetic cell separation system. For this, the BMMCs (approximately 107 cells/mL) were incubated with anti-CD11b antibodies conjugated to magnetic microbeads (MACS units; Miltenyi Biotec™, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), washed and passed through a magnetic column (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec™), where CD11b+ monocytes were retained and recovered in a buffer [0.5% PBS/0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) + 2 mmol/L EDTA]. Finally, the cells were washed and re-suspended in 0.9% sterile saline, which was later infused into the mice.

Cell characterization

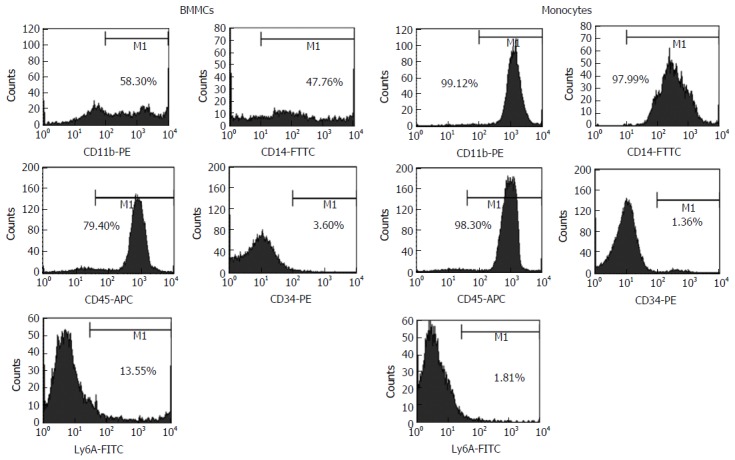

The BMMCs and monocytes obtained by immunomagnetic separation were first incubated with Anti-CD11b (PE Rat Anti-Mouse CD11b, M1/70 clone, BD Pharmingen™, San Jose, CA, United States), Anti-CD14 (FITC Rat Anti-Mouse CD14, rmC5-3 clone; BD Pharmingen™), Anti-CD45 (APC Rat Anti-Mouse CD45, 30-F11 clone; BD Pharmingen™), Anti-CD34 (PE Rat Anti-Mouse CD34, RAM34 clone; BD Pharmingen™) and Anti-Ly6A (FITC Rat Anti-Mouse Ly-6A/E, D& clone; BD Pharmingen™). After 30 min of incubation, cells were washed with 2 mL of PBS wash solution (PBS with 0.5% BSA + 0.1% sodium azide), centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min and then resuspended in 300 μL of the PBS wash solution.

The samples were then phenotypically characterized by flow cytometry (FACS Calibur; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, United States). A minimum of 10000 events/sample were collected. The cell population obtained by immunomagnetic separation presented the following phenotype distribution: 99.12% CD11b+; 97.99% CD14+; 98.3% CD45+; 1.36% CD34+; and 1.81% Ly6A+ cells; differing from those of BMMCs, which were: 58.3% CD11b+; 47.76% CD14+; 79.4% CD45+; 3.6% CD34+; and 13.55% Ly6A+ cells. These distinctive profiles demonstrated enrichment of homogeneous monocytes population in our cell preparation. Figure 1 shows representative FACS histograms of BMMCs and CD11b+ monocytes isolated by immunomagnetic separation.

Figure 1.

Representative FACS histograms of bone marrow mononuclear cells and CD11b+ monocytes isolated by immunomagnetic separation. BMMCs: Bone marrow mononuclear cells.

Cell infusion in mice with chronic liver damage

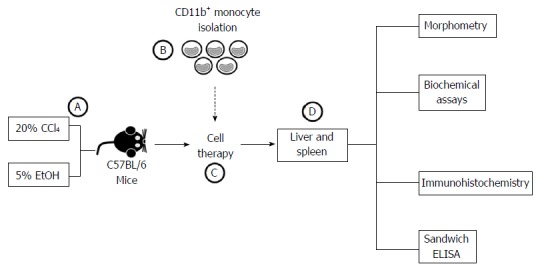

At 6 mo after treatment with CCl4/ethanol, bone marrow-derived CD11b+CD14+ monocytes and BMMCs were administered endovenously to the mice (106 cells/animal) for 3 consecutive wk. At 2 mo after transplantation, mice were euthanized and the liver and the spleen were extracted for further analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic flowchart of experimental design. A: Male C57BL/6 mice underwent chronic administration of CCl4 and EtOH solutions for 6 mo; B: Bone marrow mononuclear cells were harvested from C57BL/6 donor mice for CD11b+ monocyte isolation using immunomagnetic separation; C: Chronically liver-damaged mice underwent cell therapy; D: After 2 mo, effects of the treatment were evaluated using morphometric, biochemical, immunohistochemistry and sandwich ELISA analysis.

Morphometric evaluation

In order to characterize and quantify liver fibrosis, treated and non-treated samples were fixed for 24 h in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (5 μm) and stained with picro-Sirius. Images were obtained using an optical microscope (DM LB 2; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a JVC TK (model - C 1380; Leica, Allendale, NJ, United States) and analyzed using the Image Analysis Processing System Leica QWIN, version 2.6 MC (Leica, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Ten microscopic fields (100 × magnification) containing fibrous tissue areas were chosen for quantification. To detect and quantify Kupffer cells, the histological sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and observed under an optical microscope (DM LB 2; Leica Microsystems). The cell counts were performed in 10 fields/sections (400 × magnification).

Hydroxyproline assay

Liver samples (approximately 200 mg) were immersed in 6N HCl at approximately 120 °C for 18 h, followed by filtration. The hydroxyproline (Hyp) concentration was determined by a colorimetric assay at 558 nm as previously described[25] and expressed as nmol/g liver.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Immunohistochemistry was carried out to evaluate the activated HSCs (alpha-smooth muscle actin, α-SMA) and OPN. To stain α-SMA, liver sections (5 μm) were initially deparaffinized with xylene, dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol, incubated overnight with biotinylated antibody anti-α-SMA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, United States), and then incubated with streptavidin-peroxidase for 10 min. For OPN staining, the samples were incubated overnight with primary anti-OPN antibodies (AF808; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, United States), as previously described[5]. Thereafter, a secondary antibody bound to a synthetic polymer conjugate with peroxidase (horseradish peroxidase, HRP). 3,3’diaminobenzidine was used for staining. The sections were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin. The staining was measured in 10-fields/sections (200 × magnification) using the Image Analysis Processing System Leica QWIN, version 2.6 MC.

Glutathione measurement

To evaluate oxidative stress, the amount of glutathione (GSH) was quantified using liver fragments from mice submitted to the cell therapy and those that were not. The liver fragments were weighed, macerated in 5% metaphosphoric acid solution and centrifuged at 12000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. GSH was detected using the Glutathione Assay Kit (Sigma Aldrich) and measured with a microplate reader at 415 nm (BioRad, Hercules, CA, United States).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Frozen liver fragments (approximately 100 mg) were homogenized in a lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 300 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.02% sodium azide) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The lysates were centrifuged at 16000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and supernatants were used to quantify the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-13, IL-10, IL-17, IL-23, TGF-β1, MMP-9 and TIMP-1 by way of a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay assay following the manufacturers’ instructions (IL-13, IL-17, IL-23, MMP-9 and TIMP-1 by R&D Systems; TGF-β1: Human/Mouse TGF-beta1 by e-Bioscience, San Diego, CA, United States; TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-10 using the OptEIA Set for Mouse by BD Biosciences). Samples were read at a 450 nm wavelength using a microplate reader (Model 3550; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). The concentration of TGF-β1 was also determined from supernatants of splenocyte culture obtained from mice used in the study, as previously described[26]. The cytokine concentration was expressed in pg/mL.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were submitted to the normality test (Shapiro-Wilk’s). Differences were evaluated using the ANOVA test for parametric analysis, and the Kruskal-Wallis test with post-hoc Dunn’s test for non-parametric analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism Software (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States) and Bioestat 5.3 (Mamirauá Institute, Manaus, AM, Brazil). A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were expressed as mean values (mean ± SEM).

RESULTS

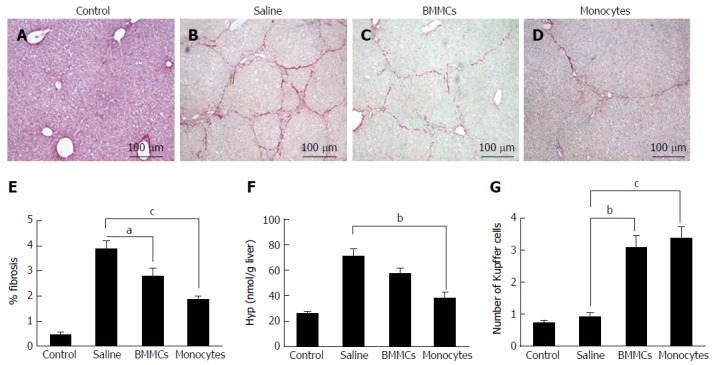

Monocyte therapy alters hepatic fibrosis

Morphometric analysis, 2 mo after therapy, showed a significant decrease in fibrotic areas in the liver from CD11b+CD14+ in the monocytes-treated group compared to the saline-treated group (P < 0.001; Figure 3B, D and E). This decrease was also found in mice treated with BMMCs (P < 0.05; Figure 3B, C and E). A marked reduction in the amount of Hyp was also observed in the group that received monocyte treatment (P < 0.01; Figure 3F). The number of Kupffer cells significantly increased in the monocyte-treated (P < 0.001) and BMMC-treated (P < 0.01) groups, when compared to the saline-treated group (Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of histological liver sections stained with picro-Sirius red. A-D: The figure shows hepatic collagens in (A) control mice, mice after CCl4 administration and treatment with (B) saline, (C) BMMCs and (D) BMMC-derived monocytes (picro-Sirius red; magnification × 100); E: Morphometric evaluation of picro-Sirius Red-stained sections; F: Hydroxyproline in liver fragments of mice undergoing cell transplantation; G: Kupffer cell count in hematoxylin-eosin-stained histological liver sections from mice who underwent CD11b+CD14+ monocyte therapy and BMMC-treated mice. aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; cP < 0.001. BMMCs: Bone marrow mononuclear cells.

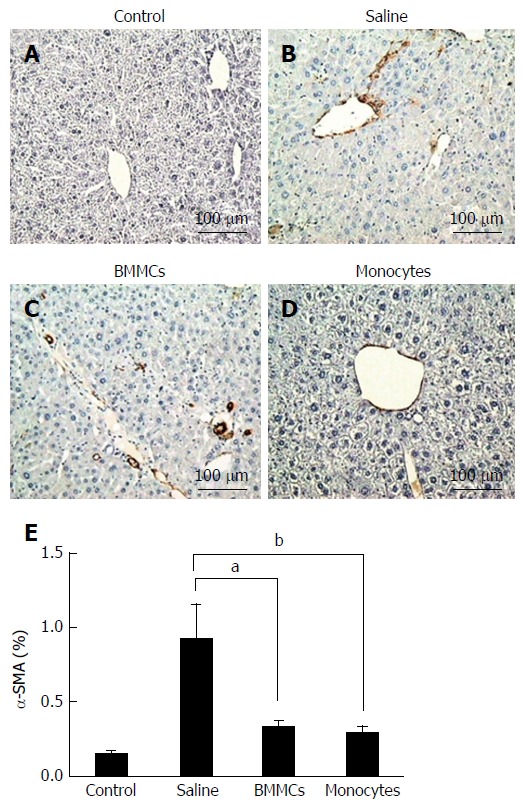

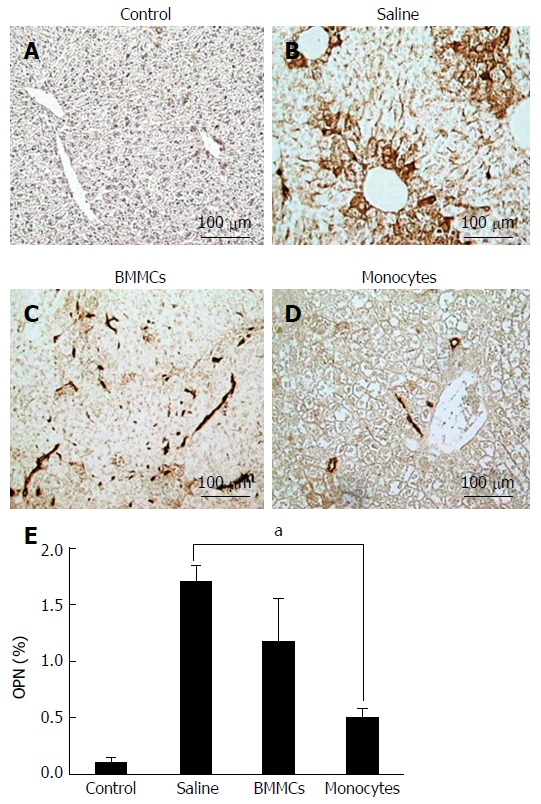

To test whether CD11b+CD14+ monocyte transplantation was able to alter the number of activated HSCs, α-SMA-positive cells were assessed by immunohistochemistry. As shown in Figure 4, α-SMA-positive cells in the hepatic parenchyma were decreased in the mice that received monocytes (P < 0.01; Figure 4D and E) as well as in the BMMC-treated group (P < 0.05; Figure 4C and E) compared with the group treated with saline (Figure 4B and E). Furthermore, OPN also decreased after CD11b+CD14+ monocyte therapy (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry for detection of α-SMA+ hepatic stellate cells in histological sections. A-D: Control (A), saline-treated (B), BMMCs-treated (C) and CD11b+CD14+ monocyte-treated (D) groups of mice (magnification × 200); E: Measurement of α-SMA+ hepatic stellate cells at 2 mo after treatment with CD11b+CD14+ monocytes and BMMCs. aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01. BMMCs: Bone marrow mononuclear cells.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry for detection of osteopontin in histological sections. A-D: Control (A), saline-treated (B), BMMCs-treated (C) and CD11b+CD14+ monocyte-treated (D) groups of mice (magnification × 200); E: Levels of hepatic OPN at 2 mo after treatment with CD11b+CD14+ monocytes. aP < 0.05. OPN: Osteopontin. BMMCs: Bone marrow mononuclear cells.

Monocyte transplantation reduces hepatic inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokine levels

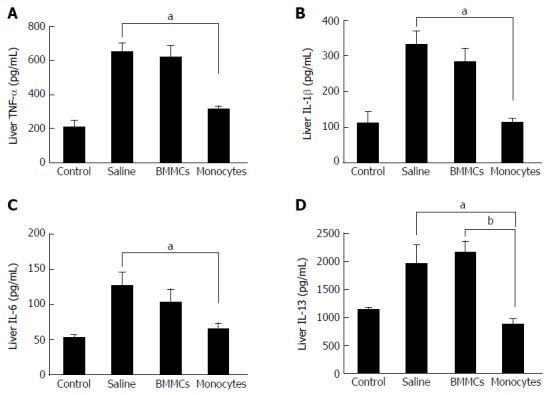

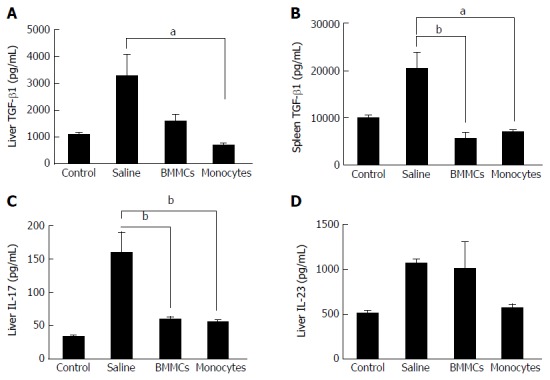

To investigate the mechanisms involved in the improvement of hepatic fibrosis after CD11b+CD14+ monocyte therapy, the levels of hepatic inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokine were quantified. The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in liver lysates were significantly lower in the CD11b+CD14+ monocytes-treated group (P < 0.05; Figure 6A-C). IL-13 (Figure 6D) and TGF-β1 (Figure 7A), important fibrogenic mediators, were significantly lower compared to those in mice treated with saline (P < 0.05). In the supernatant splenocyte culture obtained from the monocyte- and BMMC-treated groups, there was a significant decrease in TGF-β1 compared with the saline-treated mice (P < 0.05; Figure 7B). IL-17 cytokine levels were also lower in animals undergoing cell transplantation (P < 0.01; Figure 7C). A trend was also observed for decreased IL-23 cytokine levels (Figure 7D).

Figure 6.

Effects of monocyte therapy on the cytokine profile of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (A), interleukin-1β (B), interleukin-6 (C) and interleukin-13 (D), as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are represented graphically as the mean ± SEM of 5 mice/group. aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01. BMMCs: Bone marrow mononuclear cells; IL: Interleukin; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Figure 7.

Effects of monocyte-based therapy on chronically liver-damaged mice. A: Hepatic levels of TGF-β1; B: Splenic levels of TGF-β1; C and D: Hepatic levels of IL-17 (C) and IL-23 (D). aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01. TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-beta; IL: Interleukin; BMMCs: Bone marrow mononuclear cells.

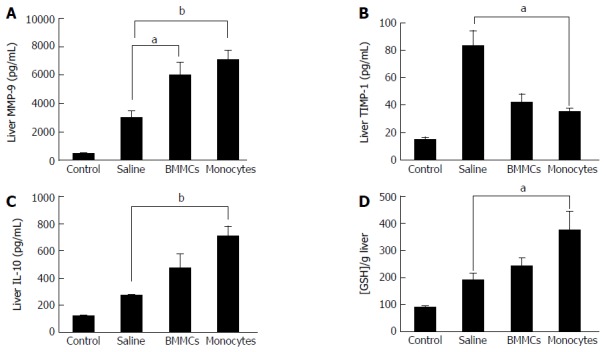

Monocyte therapy altered MMP-9, TIMP-1 and IL-10 hepatic levels

The levels of MMP-9 and TIMP-1, two relevant factors associated with liver fibrosis, were evaluated. A significant increase in the production of MMP-9 was found in animals treated with CD11b+CD14+ monocytes and BMMCs (P < 0.05; Figure 8A). Interestingly, TIMP-1 levels were significantly lower in CD11b+CD14+ monocyte-treated mice (P < 0.05; Figure 8B). The monocyte-treated group also showed significantly increased levels of IL-10 in comparison with the saline-treated group (P < 0.05; Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Effects of monocyte-based therapy on hepatic levels of matrix metalloproteinases-9 (A), tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase-1 (B), interleukin-10 (C) and glutathione (D), in chronically liver-damaged mice. aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01. MMP-9: Matrix metalloproteinases-9; TIMP: Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase; IL: Interleukin; GSH: Glutathione; BMMCs: Bone marrow mononuclear cells.

Monocyte therapy increases GSH levels

GSH levels were determined to evaluate the influence of CD11b+CD14+ monocyte therapy on oxidative stress. Monocyte-treated mice with chronic liver damage had significantly higher levels of this antioxidant molecule than the saline-treated group (P < 0.05; Figure 8D).

DISCUSSION

The present study corroborates the importance of monocytes/macrophages in liver repair. These may act to regulate some significant fibrogenic pathways, in a murine model of chronic liver damage. Monocytes/macrophages are cells with great plasticity and, depending on the tissue microenvironment, may be caused to adopt a profile that contributes to resolution/regression of experimental hepatic fibrosis[24].

The results of the present study demonstrate that transplantation of BMMC-derived CD11b+CD14+ monocytes had beneficial effects on liver lesions, thereby causing a significant reduction in fibrosis, mainly by regulating important cytokines involved in the liver repair process. Previous work carried out by our group has already shown a decrease in collagen levels in a liver undergoing BMMC therapy[14]. However, the results obtained in the present study demonstrated an improvement in these parameters on BMMC-derived CD11b+CD14+ monocyte infusion, with an almost 2-fold decrease in the collagen levels using the same experimental model.

Macrophages, important mediators of inflammatory responses, have a dichotomous response when activated, assuming a classical (M1) or alternative (M2) pathways phenotype depending on the environmental stimulus[27]. The increase in the number of hepatic resident macrophages (Kupffer cells) after cell therapy observed in our study suggests that the subsets of restorative macrophages are involved in the tissue repair by inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6)[28]. Previous studies have reported the role of macrophages in mediating liver fibrogenesis, and have proposed using macrophage subpopulations during liver damage and repair[23,29]. Treatments carried out in experimental models have shown that the infusion of bone marrow-derived macrophages decreases fibrous tissue, and enhances hepatic regeneration[22,30,31].

The decrease in fibrous liver tissue observed in the present study may be associated with the lower number of activated HSCs found. The pro-fibrogenic role of this cell type has been already reported in the literature, indicating a direct relationship between murine liver fibrosis and the rise in the number of activated HSCs[3,4]. In this regard, some studies have reported a decrease in the number of α-SMA+ cells in murine models of liver damage treated with BMMCs. This decrease is probably due to an alteration in the modulation of HSCs by specific cytokines and growth factors, including TGF-β1, TNF-α and ROS, produced by hepatocytes in a damaged liver[32]. As activation of HSCs is mediated by autocrine and paracrine signaling and these cells not only secrete cytokines but also respond to them[32], it was hypothesized that BMMC-derived CD11b+CD14+ monocytes modulate the activity of HSCs by regulating the secretion of cytokines and growth factors.

Production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine profiles of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were inhibited in mice submitted to liver damage and treated with CD11b+CD14+ monocytes. Furthermore, there was an increase in the synthesis of IL-10 cytokine, which is known for its T helper (Th)2 profile and anti-inflammatory activity[33]. These results show the influence of CD11b+CD14+ monocyte infusion in the hepatic production of inflammation and fibrogenesis mediators. The modulation of inflammation during liver repair processes by way of increased expression of IL-10 and inhibition of the production of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 is well described in the literature[34]. Because of their role in activating and proliferating HSCs, these cytokines have been implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic liver inflammation, mainly by increasing the production of collagen and regulating MMPs and TIMPs in liver damage[35,36]. Gene therapy studies have shown that the overexpression of IL-10 reduces the expression of pro-fibrotic molecules such as TGF-β1 and TNF-α[36], thereby down-regulating the inflammatory response and reducing activated HSCs, which ultimately leads to the reestablishment of liver function[35,36].

The present study found a significant decrease in TGF-β1 levels in both the extracts of liver protein and the supernatant of cultured splenocytes. These results corroborate other findings of the study, thereby indicating that transplanted monocytes play an important anti-fibrogenic role. TGF-β1 is a growth factor which plays a crucial role in initiating and maintaining liver fibrogenesis[4]. This factor is directly involved in activating HSCs and synthesizing ECM components, mostly in type I collagen[4]. It also plays an important role in inhibiting the degradation of ECM, stimulating the decrease of MMP synthesis and increasing the production of TIMPs, which leads to excessive deposition of collagen and the establishment of hepatic fibrosis[2]. Previous studies have associated the improvement of experimental liver fibrosis after BMMC-treatment with the reduction in TGF-β1 levels[20,22]. The results of the present study suggest that monocyte therapy acts through this fibrogenic pathway, thereby contributing to reducing liver fibrosis in mice.

The present investigation showed that cell transplantation caused a significant decrease in IL-17 levels, an effector pro-inflammatory cytokine, produced by CD4+ T cells[37]. This mediator induces the recruitment of inflammatory factors into liver cells and also directly activates natural hepatic immunity systems, such as those mediated by neutrophils and dendritic cells, to release cytokines that perpetuate chronic inflammation[38]. Previous reports have reported that Th17 cells are able to participate in the pathogenesis of hepatic lesions associated with hepatitis B virus[39]. Recently, emerging evidence has indicated that IL- 17 may be implicated in the induction of liver fibrosis, contributing to the activation of HSCs in vitro[39].

OPN is a glycoprotein expressed in a variety of tissues, mainly found in ECM and sites of healing wounds[40]. Studies have shown that this protein is highly expressed in fibrotic liver tissue and influences the function of hepatic progenitors[41]. Under this condition, increases in the level of TGF-β and activation of HSCs could be also observed[6,41]. It thus seems reasonable to suppose that deactivation of OPN could lead to attenuation of liver fibrosis[1,8]. The results of the present study accordingly showed a significant decrease in the production of OPN and in the number of activated HSCs.

GSH is an important antioxidant molecule that acts as a modulator of redox signaling, cell proliferation, apoptosis, immune responses and fibrogenesis[42,43]. Reduced levels of this molecule have been found in preclinical fibrosis models and in human fibrotic diseases[42]. A previous study has shown that higher GSH production inhibits the fibrogenic activity of TGF-β1[43]. The present study also found an increase in this molecule after CD11b+CD14+ monocyte transplantation, suggesting an association between the anti-fibrotic effects observed in the monocyte-treated group and increased antioxidant activity of this cell population.

Alterations in the quantities of some molecules involved in fibrogenesis, as well as fibrous tissue remodeling, were assayed in this study. The CD11b+CD14+ monocyte therapy in mice with chronic liver damage caused an increase in MMP-9 hepatic levels. Previous studies have associated reduced liver fibrosis with fibrous tissue degradation[3]. MMP-9 plays an important role in resolving liver fibrosis and has been considered a potent therapeutic target[11]. Yang et al[44] suggest that, in the hepatic microenvironment, macrophage subpopulations play an anti-fibrotic role, as they express several MMPs, including MMP-9, which are directly involved in degrading ECM, facilitating the resolution of hepatic fibrosis.

CD11b+CD14+ monocyte transplantation gave rise to a reduction in hepatic TIMP-1 and IL-13, two important pro-fibrogenic mediators. TIMPs are involved in the regulation of fibrogenic response by inhibiting the enzymatic activity of MMPs, having an anti-apoptotic effect on HSCs[9]. The presence of high quantities of these inhibitors in chronically damaged hepatic tissue may contribute to the establishment of liver fibrosis[45]. IL-13 is a cytokine associated with severe forms of schistosomal liver fibrosis as well as non-schistosomiasis liver diseases[46]. IL-13 is considered one of the central mediators in liver pathogenesis and is involved in TGF-β1 production by liver cells, besides its ability to induce progenitor cells to transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts, which produce collagen[47]. The data produced by the present study corroborates the protective role of monocytes/macrophages in tissue repair processes, by way of fibrogenic pathways.

Several studies have attempted to identify and to correlate different macrophage profiles to tissue repair processes[29,30,48]. Ramachandran et al[29] found that Ly6Clow macrophages secrete large amounts of fibrolytic MMPs such as MMP-9 and MMP-13, as well as IL-10. Therefore, the increase in secretion of MMP-9 and IL-10 observed in this study suggests a down-regulation of the activation pathways that lead to the chronic inflammatory response.

In conclusion, the present study shows the important contribution of bone marrow-derived monocyte/macrophage cell therapy for improving the state of liver fibrosis in a murine model of chronic liver damage. These cells act to modulate inflammation and fibrogenesis and regulate the oxidative stress caused by damaged tissue. Further studies should be conducted to establish a promising therapeutic tool for treating chronic liver diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr Roni E. Araujo for the preparation of histological sections, and the animal facility of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and Aggeu Magalhães Research Center, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, in Recife, Brazil.

COMMENTS

Background

Chronic liver disease is characterized by alterations in the process of tissue repair, such as the excessive deposition of fibrous tissue and the inhibition of the dynamics of regeneration. The knowledge on bone marrow cell therapy has opened new perspectives towards treatment of hepatic diseases. However, the cell types involved in liver recovery have not been fully elucidated. Monocytes have emerged as one set of potential candidates, due to their plasticity and involvement in inflammation and tissue repair.

Research frontiers

Previous experiments have already shown that bone marrow cell transplantation promotes improvement in the experimental model of liver fibrosis. The monocyte/macrophage lineage may have important therapeutic potential in chronic liver diseases.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is an innovative study that evaluated the effects of monocyte transplantation isolated from bone marrow mononuclear cells, by morphological, biochemical and immunological assays.

Applications

Experimental hepatic fibrosis improvement after cell therapy reinforces the potential involvement of monocytes/macrophages in liver repair, being able to acquire pro-resolute profile, acting in the regulation of some relevant inflammatory and fibrogenic pathways.

Terminology

Bone marrow mononuclear cells are used to collectively denominate bone marrow cells, whose nuclei are unilobulated and which lack granules in the cytoplasm. This cell population includes hematopoietic progenitor cells, lymphoid cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells) and monocytes.

Peer-review

The authors addressed an interesting, clinically relevant and important issue aiming to modify the state of chronic liver disease. To approach this goal, the authors purified bone marrow-derived CD11bhigh monocytes, which were transfused to mice prior to the administration of the provoking agents, i.e., ethanol and carbon tetrachloride. Using a C57BL/6 mouse model system, they showed that the transfusion of monocytes was more effective to decrease IL-13 levels in the liver as compared to the infusion of BMMCs. The authors also demonstrated that monocyte transfusion could reduce the size of the fibrotic area, the amount of hydroxyproline and the concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines, while the levels of interleukin-10 cytokine and the number of Kupffer cells in the liver were increased as compared to saline transfusion. Due to the limited information of cell-based therapies in chronic inflammatory diseases, the identification of immunostimulatory and regulatory pathways in a preclinical setting and in the context of liver metabolism is of high importance.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional animal care and use committee statement: All procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Aggeu Magalhães Research Center (Protocol No. 15/2011).

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no actual or potential conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: January 4, 2017

First decision: February 9, 2017

Article in press: April 12, 2017

P- Reviewer: Huber R, Rajnavolgyi E S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Wang P, Koyama Y, Liu X, Xu J, Ma HY, Liang S, Kim IH, Brenner DA, Kisseleva T. Promising Therapy Candidates for Liver Fibrosis. Front Physiol. 2016;7:47. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou WC, Zhang QB, Qiao L. Pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7312–7324. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Troeger JS, Mederacke I, Gwak GY, Dapito DH, Mu X, Hsu CC, Pradere JP, Friedman RA, Schwabe RF. Deactivation of hepatic stellate cells during liver fibrosis resolution in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1073–1083.e22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang JX, Török NJ. Liver Injury and the Activation of the Hepatic Myofibroblasts. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2013;1:215–223. doi: 10.1007/s40139-013-0019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira TA, Syn WK, Machado MV, Vidigal PV, Resende V, Voieta I, Xie G, Otoni A, Souza MM, Santos ET, et al. Schistosome-induced cholangiocyte proliferation and osteopontin secretion correlate with fibrosis and portal hypertension in human and murine schistosomiasis mansoni. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015;129:875–883. doi: 10.1042/CS20150117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seth D, Duly A, Kuo PC, McCaughan GW, Haber PS. Osteopontin is an important mediator of alcoholic liver disease via hepatic stellate cell activation. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13088–13104. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.13088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pritchett J, Harvey E, Athwal V, Berry A, Rowe C, Oakley F, Moles A, Mann DA, Bobola N, Sharrocks AD, et al. Osteopontin is a novel downstream target of SOX9 with diagnostic implications for progression of liver fibrosis in humans. Hepatology. 2012;56:1108–1116. doi: 10.1002/hep.25758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coombes JD, Choi SS, Swiderska-Syn M, Manka P, Reid DT, Palma E, Briones-Orta MA, Xie G, Younis R, Kitamura N, et al. Osteopontin is a proximal effector of leptin-mediated non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1572–1585. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das SK, Vasudevan DM. Genesis of hepatic fibrosis and its biochemical markers. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2008;68:260–269. doi: 10.1080/00365510701668516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pham Van T, Couchie D, Martin-Garcia N, Laperche Y, Zafrani ES, Mavier P. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 and of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in liver regeneration from oval cells in rat. Matrix Biol. 2008;27:674–681. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarygin KN, Lupatov AY, Kholodenko IV. Cell-based therapies of liver diseases: age-related challenges. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1909–1924. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S97926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chistiakov DA. Liver regenerative medicine: advances and challenges. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;196:291–312. doi: 10.1159/000335697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Oliveira SA, de Freitas Souza BS, Sá Barreto EP, Kaneto CM, Neto HA, Azevedo CM, Guimarães ET, de Freitas LA, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos R, Soares MB. Reduction of galectin-3 expression and liver fibrosis after cell therapy in a mouse model of cirrhosis. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:339–349. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.637668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyra AC, Soares MB, da Silva LF, Braga EL, Oliveira SA, Fortes MF, Silva AG, Brustolim D, Genser B, Dos Santos RR, et al. Infusion of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells through hepatic artery results in a short-term improvement of liver function in patients with chronic liver disease: A pilot randomized controlled study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22 Suppl 1:33–42. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832eb69a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bai YQ, Yang YX, Yang YG, Ding SZ, Jin FL, Cao MB, Zhang YR, Zhang BY. Outcomes of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in decompensated liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8660–8666. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Freitas Souza BS, Nascimento RC, de Oliveira SA, Vasconcelos JF, Kaneto CM, de Carvalho LF, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos R, Soares MB, de Freitas LA. Transplantation of bone marrow cells decreases tumor necrosis factor-α production and blood-brain barrier permeability and improves survival in a mouse model of acetaminophen-induced acute liver disease. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:1011–1021. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.684445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali G, Masoud MS. Bone marrow cells ameliorate liver fibrosis and express albumin after transplantation in CCl4-induced fibrotic liver. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:263–267. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.98433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roderfeld M, Rath T, Pasupuleti S, Zimmermann M, Neumann C, Churin Y, Dierkes C, Voswinckel R, Barth PJ, Zahner D, et al. Bone marrow transplantation improves hepatic fibrosis in Abcb4-/- mice via Th1 response and matrix metalloproteinase activity. Gut. 2012;61:907–916. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliveira SA, Souza BS, Guimaraes-Ferreira CA, Barreto ES, Souza SC, Freitas LA, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos R, Soares MB. Therapy with bone marrow cells reduces liver alterations in mice chronically infected by Schistosoma mansoni. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5842–5850. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan L, Han Y, Wang J, Liu J, Hong L, Fan D. Peripheral blood monocytes from patients with HBV related decompensated liver cirrhosis can differentiate into functional hepatocytes. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:949–954. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas JA, Pope C, Wojtacha D, Robson AJ, Gordon-Walker TT, Hartland S, Ramachandran P, Van Deemter M, Hume DA, Iredale JP, et al. Macrophage therapy for murine liver fibrosis recruits host effector cells improving fibrosis, regeneration and function. Hepatology. 2011;53 Suppl 6:2003–2015. doi: 10.1002/hep.24315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, Clay S, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, Wu S, Lang R, Iredale JP. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wynn TA, Vannella KM. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity. 2016;44:450–462. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergman I, Loxley R. Two improved and simplified methods for the spectrophometric determination of hydroxyproline. Ann Chem. 1963;35:1961–1965. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barros AF, Oliveira SA, Carvalho CL, Silva FL, Souza VC, Silva AL, Araujo RE, Souza BS, Soares MB, Costa VM, et al. Low transformation growth factor-β1 production and collagen synthesis correlate with the lack of hepatic periportal fibrosis development in undernourished mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109:210–219. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276140266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahbub S, Deburghgraeve CR, Kovacs EJ. Advanced age impairs macrophage polarization. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32:18–26. doi: 10.1089/jir.2011.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ju C, Tacke F. Hepatic macrophages in homeostasis and liver diseases: from pathogenesis to novel therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:316–327. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramachandran P, Pellicoro A, Vernon MA, Boulter L, Aucott RL, Ali A, Hartland SN, Snowdon VK, Cappon A, Gordon-Walker TT, et al. Differential Ly-6C expression identifies the recruited macrophage phenotype, which orchestrates the regression of murine liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E3186–E3195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119964109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suh YG, Kim JK, Byun JS, Yi HS, Lee YS, Eun HS, Kim SY, Han KH, Lee KS, Duester G, et al. CD11b(+) Gr1(+) bone marrow cells ameliorate liver fibrosis by producing interleukin-10 in mice. Hepatology. 2012;56:1902–1912. doi: 10.1002/hep.25817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore JK, Mackinnon AC, Wojtacha D, Pope C, Fraser AR, Burgoyne P, Bailey L, Pass C, Atkinson A, Mcgowan NW, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of macrophages with therapeutic potential generated from human cirrhotic monocytes in a cohort study. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:1604–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jang YO, Jun BG, Baik SK, Kim MY, Kwon SO. Inhibition of hepatic stellate cells by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in hepatic fibrosis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21:141–149. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2015.21.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao L, Xing S, Fu X, Song H, Wang Z, Tang J, Zhao Y. Association between interleukin-10 gene promoter polymorphisms and susceptibility to liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:11680–11684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma HC, Wang X, Wu MN, Zhao X, Yuan XW, Shi XL. Interleukin-10 Contributes to Therapeutic Effect of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Acute Liver Failure via Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Signaling Pathway. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129:967–975. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.179794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robert S, Gicquel T, Bodin A, Lagente V, Boichot E. Characterization of the MMP/TIMP Imbalance and Collagen Production Induced by IL-1β or TNF-α Release from Human Hepatic Stellate Cells. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hung KS, Lee TH, Chou WY, Wu CL, Cho CL, Lu CN, Jawan B, Wang CH. Interleukin-10 gene therapy reverses thioacetamide-induced liver fibrosis in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weaver CT, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Harrington LE. IL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T cell lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yasumi Y, Takikawa Y, Endo R, Suzuki K. Interleukin-17 as a new marker of severity of acute hepatic injury. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L, Chen S, Xu K. IL-17 expression is correlated with hepatitis Brelated liver diseases and fibrosis. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27:385–392. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subraman V, Thiyagarajan M, Malathi N, Rajan ST. OPN -Revisited. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:ZE10–ZE13. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12872.6111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lancha A, Rodríguez A, Catalán V, Becerril S, Sáinz N, Ramírez B, Burrell MA, Salvador J, Frühbeck G, Gómez-Ambrosi J. Osteopontin deletion prevents the development of obesity and hepatic steatosis via impaired adipose tissue matrix remodeling and reduced inflammation and fibrosis in adipose tissue and liver in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu RM, Gaston Pravia KA. Oxidative stress and glutathione in TGF-beta-mediated fibrogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu SC. Glutathione synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3143–3153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang L, Kwon J, Popov Y, Gajdos GB, Ordog T, Brekken RA, Mukhopadhyay D, Schuppan D, Bi Y, Simonetto D, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes fibrosis resolution and repair in mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1339–1350.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elpek GÖ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis: An update. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7260–7276. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Munker S, Müllenbach R, Weng HL. IL-13 Signaling in Liver Fibrogenesis. Front Immunol. 2012;3:116. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pellicoro A, Ramachandran P, Iredale JP, Fallowfield JA. Liver fibrosis and repair: immune regulation of wound healing in a solid organ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:181–194. doi: 10.1038/nri3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tacke F, Zimmermann HW. Macrophage heterogeneity in liver injury and fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1090–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]