Highlights

-

•

Reassurance is a frequently utilized yet poorly understood clinical skill.

-

•

Emotional distress is an important driver of healthcare use.

-

•

Diagnostic test results are not reassuring.

-

•

Some attempts at reassurance can increase rather than decrease concern.

-

•

Patient education is a promising way for clinicians to manage emotional distress.

Keywords: Patient education, Preventive health services, Low back pain, Emotions

Abstract

Introduction

Reassurance is the removal of fears and concerns about illness. In practice reassurance for non-specific conditions, where a diagnosis is unclear or unavailable, is difficult and can have unexpected effects. Many clinical guidelines for non-specific conditions such as low back pain recommend reassurance. Until recently, there was little evidence on how to reassure patients effectively.

Results

High distress causes patients to consult more often for low back pain. To reduce distress, clinicians should provide structured education, which is effective in the short- and long-term. A newly developed online prognostic tool has the potential to improve the quality of reassurance and reduce the number of inappropriate interventions provided for low back pain.

Conclusion

Targeted reassurance, including enhanced, prognosis-specific education, could optimize reassurance and possibly prevent disabling symptoms.

Introduction

Reassurance is the removal of fears and concerns about illness.1 In medicine, reassurance can refer to the behavior of a caregiver,2 or to the response of a patient.3 Reassurance is said to have been successful if a patient responds to a clinical consultation with less fear and concern about their illness.4 Despite being a core aspect of medical care, and the cornerstone of management for a number of non-specific conditions,5, 6, 7 reassurance is a clinical skill that remains poorly understood. In non-specific conditions such as low back pain, where a diagnosis is unclear or unavailable, reassurance is particularly difficult. The success of primary health care relies on effective management of emotional distress in these patients.8 Historically, however, clinical observations, theoretical models and experimental data suggest the process of reducing emotional distress with reassurance is not straightforward.

Clinical observations

Reassurance has been the topic of clinical observation and commentary in general medical journals since the 1970s.9, 10 Authors such as Kessel9 and Sapira10 saw reassurance as essentially a psychotherapeutic technique rather than an inevitable byproduct of a medical consultation. As such, the clinical approach to formal reassurance at this time was based partly on psychotherapy principles and partly on clinical intuition: psychotherapeutic in that practitioners explored the patient's, often hidden, fears and concerns; and intuitive in that the natural desire of a caregiver was to alleviate a patient's concerns.10

There appears to be no consensus among clinicians over exactly how practitioners should behave in order to reassure a patient. Some authors believe practitioners should be primarily empathic and collaborative.10, 11 Sapira10 felt that a lack of empathy when attempting reassurance would ultimately cause patients to feel misunderstood and seek another opinion. Other authors consider authority, paternalism and objectivity to be the essential characteristics of a reassuring practitioner.9, 12 Kessel,9 for example, believed that “Sick people want their doctor to take charge”. There is debate about whether practitioners need to repeat reassurance because this could either reinforce a positive message9, 10 or, on the contrary, give the impression of uncertainty.13

Most authors agree that effective reassurance should, like any medical encounter, involve some form of data gathering followed by information giving.9, 10, 11, 14 Data gathering refers to when practitioners, through questioning, examination, and testing, collect data on the physical and emotional aspects of a patient's illness.11 Based on these findings, practitioners then provide the patient with information about the nature of their illness and decide on a management plan. While commentators have viewed these stages as essential aspects of the medical encounter,11 it is unclear to what extent these stages are important. For example, the manner in which a practitioner collects data, e.g. through taking a thorough history and performing a physical examination, might in itself be reassuring.9 Generic information giving through mass media campaigns might be reassuring even without the data gathering stage.15 Furthermore, there is no agreement on either the most important data to gather, or the most important information to give, during a consultation in order to optimize reassurance.

The process of data gathering and information giving is particularly challenging in non-specific conditions. In these conditions, collecting the usual clinical data from routine diagnostic tests and investigations is not recommended by guidelines.5, 6, 7 Is it possible to confidently reassure these patients without having collected those data? In the information giving stage, Gask and Usherwood11 suggest that the information should at the very least be tailored to what the patient already knows, what they want to know, and what they need to know. Giving information on diagnosis, prognosis and the role of emotional factors appears to be important.16 However, if diagnosis and prognosis is unclear or unavailable, as is often the case in non-specific conditions such as low back pain, how should a practitioner proceed? Is it satisfactory to focus on the absence of disease,10 on alternative explanations for the symptoms,11 or perhaps a combination of the two?

Research to date has offered no clear guidance or consensus on what constitutes a reassuring consultation. There is, however, one consistently observed phenomenon: attempts at reassurance have the potential to increase concern.17, 18 To illustrate this point Fantry,12 a physician, reported on the effects of assurances from medical staff who were caring for her severely injured brother. She noted that regular emotional assurances such as “everything will be fine” and “his pupils seem more reactive today” could increase or decrease her family members’ emotional distress more than any objective medical data:

“[my family] “felt as if they were on a roller-coaster ride,” which is not because my brother's hospital course itself was filled with days of progress and setbacks. Rather, it was just the opposite. But their emotions were not based on a review of his most recent labs, CT scan, and coma score.” Fantry et al.12, Page 1338, Final paragraph.

From this experience on the other side of the patient-physician consultation, Fantry suggested that doctors should focus more on providing accurate prognostic and diagnostic information, and less on providing intuitively reassuring remarks such as knee-jerk platitudes and messages of hope.

Indeed, their narrative review of reassurance for painful conditions, Linton et al.4 question whether, because of its potential to increase concern, recommendations to reassure patients in pain might in fact be premature: “…the effects of reassurance on pain related problems are inconsistent, sometimes small, sometimes transient, and sometimes paradoxical. Thus, general recommendations for reassurance appear premature and a better understanding is needed.” Linton et al.4, Page 7, Paragraph 3.

Theoretical models of reassurance

Pincus et al.2 formalized some of the intuitive aspects of reassurance for patients with non-specific symptoms. These authors combined historical ideas such as the need to gather data from a patient and to provide information about their condition, with the role of empathy and some principles of persuasion, to propose a theoretical model of reassurance. The model, an extension of Coia and Morley's19 work in medical reassurance for psychosomatic illness, categorizes styles of reassurance as affective or cognitive. Affective reassurance aims to enhance the patient-practitioner relationship e.g. rapport building, empathic communication and simple assurances that everything will be ok. Cognitive reassurance aims to enhance a patient's knowledge and understanding of their health problem, for example using patient education to reduce worry and promote appropriate health service use. Pincus's model2 is yet to be formally tested.

For patients with low back pain, perhaps the most common example of a non-specific condition, the concept of reassurance aligns well with the Fear Avoidance Model.20 Until recently, the Fear Avoidance Model largely underpinned the recommendations to reassure patients with low back pain.4, 21 In contrast to Pincus's model, which does not address the role of pain-related fear, the Fear Avoidance Model outlines how fear, worry, and illness information can lead to chronic disability. However, rather than focus on reassurance per se, the Fear Avoidance Model outlines how fear and worry when left untreated or when worsened by harmful illness information leads to disability. For example, the model suggests providing harmful illness information to patients can increase worry, catastrophization (holding a catastrophic view of one's symptoms and prognosis), and negative affect. This in turn increases fear of pain/harm and leads to avoidance, disuse and depression.

Neither of these models of reassurance has been able to explain how to best reduce fear and concern about physical symptoms such as low back pain. How, for example, can a practitioner convince a patient that there is no serious illness or threat when that patient is experiencing severe pain? Pincus et al.2 provide no explanation for how reassurance might influence symptoms directly nor do they include the role of pain-related fear, despite there being clear evidence that contextual factors, such as fear and concern, directly influence pain and disability.22 Although the Fear Avoidance Model considers the role of fear and iatrogenesis in the development of disability, it does not consider how practitioners might change these factors. Furthermore, neither model postulates on the role of reassurance in the development of chronic pain.

Evidence on how to provide reassurance

Perhaps the most widely investigated method of reassurance has been the use of negative diagnostic test results. Many practitioners order diagnostic tests because they expect evidence of no serious disease will be reassuring.3 A number of randomized trials have now investigated how patients respond after they have been provided with negative diagnostic tests. As predicted by Warwick and Salkovskis13 back in 1985, the effects of diagnostic tests on measures of concern are at best unpredictable.23 In low back pain there is high quality evidence that providing radiological reports does not reduce concern3, 24 and might worsen disability outcomes.25 Although MRI results showing no serious pathology can be reassuring for patients with headache, results are not maintained in the long term.26 There is convincing evidence from systematic reviews in mixed non-specific conditions3, 24 that negative diagnostic tests do not lead patients to respond with less fear or concern about illness.

Another practitioner behavior that has been investigated by clinical trials, and where the goal is reassurance, is patient education. There is preliminary evidence that cognitive reassurance (information, education), but not affective reassurance (rapport building, empathy), can reduce fears and concerns in the long term.2 Modern education techniques, such as those focused on pain biology,27 also appear to reduce catastrophizing more than conventional education.28 Our recent systematic review found high quality evidence (14 trials, n = 4872) that patient education can reduce fears about back pain and subsequent health services use.29 Interventions that were as short as 5-min duration had reassuring effects for up to 12-months. There was also evidence that the professional background of the educator could influence outcomes: physicians were more effective than physical therapists or nurses.

Optimizing patient education to reassure patients

While patient education appears to be an effective method of reassurance, the effect sizes are small. Other studies have investigated strategies that could increase the effects of patient education. For example, after noting the influence of professional background on the effectiveness of reassurance, we attempted to enhance the credibility, or believability, of a physical therapist providing patient education.30 This randomized trial found that dressing in formal attire did not influence the credibility of patient education and was therefore unlikely to optimize the effects of these treatments in primary care.

A second strategy for optimizing reassurance has been to target patient education to patients with a poor prognosis. For example, we have developed a prognostic model – the PICKUP (Preventing the Inception of Chronic Pain) model – that can successfully predict the onset of chronic low back pain. The results of the PICKUP research suggested that to date, this model has the highest predictive accuracy of any currently available model for patients with acute low back pain. We found evidence that using the model in Australian primary care could lead a 40% reduction in unnecessary interventions for patients with a good prognosis.31 We also investigated the causal role of emotional distress in health services overuse for low back pain.32 The results showed that, after controlling for known confounding factors, emotional distress was an important cause of ongoing health services use after an episode of low back pain. Together these findings suggest that targeting emotional distress in patients with a poor prognosis with reassurance could be an effective way to prevent problematic low back pain. The Prevent Trial,33 a large multi-center randomized trial has investigated that very question. This trial compared two distinct types of reassurance: one focused on listening and data gathering (sham education), and the other focused on information giving (pain biology education). Although the final results of this study are yet to be published, this will be the first placebo-controlled trial of reassurance for low back pain.

Implications of recent findings on reassurance

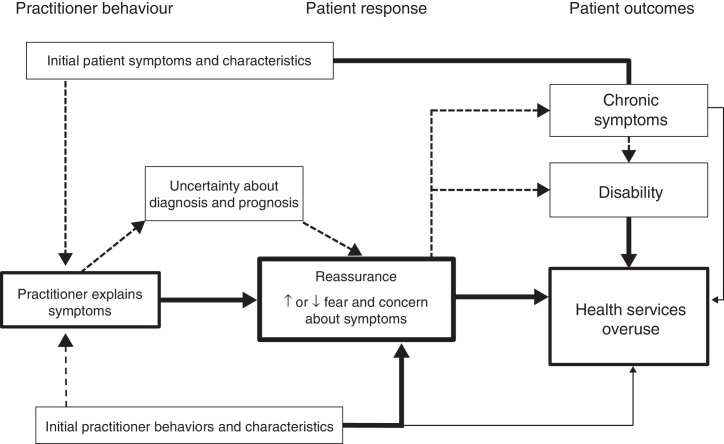

Because emotional distress causes increased healthcare use, reducing emotional distress through effective reassurance is likely to reduce the health services overuse problem in low back pain (Fig. 1). There is also potential for this finding to generalize to other health conditions. For example, areas where health service overuse is problematic include antibiotic use for the common cold,34 arthroscopic knee surgery for degenerative meniscus tears,35 and prostatectomy for low-risk prostate cancer.36 Identifying and treating emotional distress in patients seeking these services, for example through patient education, might be a worthwhile research endeavor in the campaign to reduce overuse. Unfortunately, while it is brief and easy to implement, patient education alone has only modest effects. Attempting to optimize these effects is also not straight forward; long, multi-session interventions are not more reassuring than a single consultation, and modern biopsychosocial content is not more reassuring than traditional biomedical content. Furthermore, the credibility of reassurance cannot be improved by manipulating simple characteristics of a practitioner such as their professional attire. When taken together, these findings suggest that reassurance is a clinical skill that is probably more important, and more difficult, than practitioners and researchers might expect.

Figure 1.

Model of reassurance and health services overuse for acute non-specific symptoms. Solid arrows = evidence of a causal relationship. Broken arrows = hypothesized causal relationship. Figure should be read from left to right. Explaining symptoms can lead to reduced uncertainty, reduced fear and concern, and thereby reduce health services use. Explaining symptoms might reduce health services use directly through symptom reappraisal, or indirectly through reducing symptoms that drive health services use. Practitioners can influence health services overuse by using explanations that aim to reduce fear and concern.

Recommendations for practice

The PICKUP prognostic model is a ready-to-use clinical tool that can identify patients who are likely to recover quickly and those who are at high-risk of chronic pain. Patients identified as being high-risk of chronic pain may need more sophisticated reassurance than basic information about the benign nature of low back pain. In fact, one could argue that assuring patients in this high-risk group that low back pain is benign, would constitute false reassurance. These patients have a high symptom burden and a high level of emotional distress. Because emotional distress is causally related to health outcomes, namely health services use, structured interventions to reduce emotional distress, such as cognitive behavioral therapy,37 and mindfulness-based stress reduction,38 could therefore be useful early intervention options for this high-risk group. Unfortunately, these interventions are resource intensive and only likely to be beneficial for those with a very poor prognostic profile. A key advantage of the pain biology education approach is that practitioners can provide that intervention in two consultations. Results from the Prevent Trial will provide much needed data on whether pain biology education is adequate to manage emotional distress in this high-risk group.

Practitioners should expect patient education to reduce some, but not all, aspects of emotional distress. Education that was brief and accompanied by written information yielded the largest effects on the ‘fear’ component of emotional distress. Interestingly, patient education did not change the ‘concern’ component of emotional distress (anxiety, worry, catastrophization), which suggests other strategies are needed to manage these factors. Pain biology education, which has been shown to reduce catatrophising,39 is a promising option. Furthermore, there is no evidence that conventional patient education can change depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms are an important prognostic factor and they are particularly influential on long-term health services overuse. While cognitive behavioral therapy is perhaps the most well-known strategy for reducing depressive symptoms in primary care, simpler strategies delivered by non-psychologists are needed and might be an equally effective alternative.40

Professional background has the potential to suppress or enhance the effects of reassurance. Allied health practitioners should also consider ways to boost their credibility. Although the positioning of medical equipment in a clinic room has been shown to boost believability in one study,41 these findings have not been replicated. Alternatively, practitioners could try shifting the focus of education to what the patient really wants to know about.11 Practitioners who focus more on the data gathering stage of the consultation and target their education to the specific concerns of the patient, could be more successful that those who provide generic educational messages. Reducing the threat value of these data, such as thoughts and beliefs about low back pain, can reduce pain intensity.42 Communication skills are likely to be important and formal training in providing a “good back consultation” might enhance the effects reassurance. It is also plausible that allied health practitioners might benefit from Kessel's9 idea of the reassuring doctor, who:

“…appears strong, firm in his [sic] purpose, absolutely dependable, unable to be upset by anything the patient may say or do, unflustered, unembarrassable, unassailable, free from weakness.” Kessel9, Page 1129, Paragraph 2.

Recommendations for research

Discussing risk using prognostic models can reduce distress in conditions such as breast cancer,43 and reduce the likelihood of unnecessary, invasive intervention in other cancers.44 Prognostic profiling in primary care could be a useful starting point for improving the effects of reassurance. Risk communication also has the potential to fulfill a fundamental requirement of effective reassurance: removing uncertainty. Using a clinical tool such as PICKUP can help identify trial participants who would be appropriate for minimal intervention. These are patients that a practitioner could confidently reassure of a positive prognosis, and support this assurance with evidence in the form of individualized risk data. A website that accompanies the PICKUP publications (http://myback.neura.edu.au/)45 will facilitate formal testing of this approach.

Future randomized trials should test novel methods to alleviate emotional distress in patients with physical symptoms. The model presented in Fig. 1 can also be used to guide research. Keys areas of uncertainty include the mediating role of reassurance and the effect of practitioners providing different explanations of symptoms, on functional outcomes. Patient decision aids and infographics have been shown to inform health decision-making and motivate behavior change across multiple medical conditions44 but are largely untested in low back pain. Combining personalized educational content with novel information delivery methods, e.g. via social media platforms such as Twitter, has the potential to provide reassurance on a global scale.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

AT is supported by an NHMRC PhD Scholarship. JM, EO, and AC are supported by NHMRC Project Grants 1047827 and 1087045.

References

- 1.Oxford University Press . 2000. The Oxford English Dictionary Online. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/44108?redirectedFrom=credibility-eid Accessed 14.06.16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pincus T., Holt N., Vogel S. Cognitive and affective reassurance and patient outcomes in primary care: a systematic review. Pain. 2013;154(11):2407–2416. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolfe A., Burton C. Reassurance after diagnostic testing with a low pretest probability of serious disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):407–416. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linton S.J., McCracken L.M., Vlaeyen J.W. Reassurance: help or hinder in the treatment of pain. Pain. 2008;134(1–2):5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koes B.W., van Tulder M., Lin C.W., Macedo L.G., McAuley J., Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(12):2075–2094. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan S., Chang L. Diagnosis and management of IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(10):565–581. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’ Flynn N., Timmis A., Henderson R., Rajesh S., Fenu E. Management of stable angina: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;343:d4147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Declaration of Alma-Ata. Paper Presented at: International Conference on Primary Health Care; Alma-Ata, USSR; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessel N. Reassurance. Lancet. 1979;313(8126):1128–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)91804-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sapira J.D. Reassurance therapy. What to say to symptomatic patients with benign diseases. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77(4):603–604. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gask L., Usherwood T. ABC of psychological medicine. The consultation. BMJ. 2002;324(7353):1567–1569. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7353.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fantry A. Say what you mean, mean what you say. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1337–1338. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warwick H., Salkovskis P.M. Reassurance. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 1985;290(6474):1028. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6474.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchsbaum D.G. Reassurance reconsidered. Soc Sci Med. 1986;23(4):423–427. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchbinder R., Jolley D., Wyatt M. Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: effects of a media campaign on back pain beliefs and its potential influence on management of low back pain in general practice. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26(23):2535–2542. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laerum E., Indahl A., Skouen J. What is “the good back-consultation”? A combined qualitative and quantitative study of chronic low back pain patients’ interaction with and perceptions of consultations with specialists. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38(4):255. doi: 10.1080/16501970600613461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rief W., Heitmuller A.M., Reisberg K., Ruddel H. Why reassurance fails in patients with unexplained symptoms—an experimental investigation of remembered probabilities. PLOS Med. 2006;3(8):e269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucock M.P., Morley S., White C., Peake M.D. Responses of consecutive patients to reassurance after gastroscopy: results of self administered questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1997;315(7108):572–575. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7108.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coia P., Morley S. Medical reassurance and patients’ responses. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45(5):377–386. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vlaeyen J.W., Linton S.J. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85(3):317–332. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholas M.K., George S.Z. Psychologically informed interventions for low back pain: an update for physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):765–776. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Blasi Z., Harkness E., Ernst E., Georgiou A., Kleijnen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2001;357(9258):757–762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald I., Daly J., Jelinek V., Panetta F., Gutman J. Opening Pandora's box: the unpredictability of reassurance by a normal test result. BMJ. 1996;313(7053):329–332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7053.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Ravesteijn H., van Dijk I., Darmon D. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chou R., Fu R., Carrino J.A., Deyo R.A. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):463–472. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard L., Wessely S., Leese M. Are investigations anxiolytic or anxiogenic? A randomised controlled trial of neuroimaging to provide reassurance in chronic daily headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(11):1558–1564. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.057851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moseley G.L., Butler D.S. Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future. J Pain. 2015;16(9):807–813. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moseley G.L., Nicholas M.K., Hodges P.W. A randomized controlled trial of intensive neurophysiology education in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(5):324–330. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traeger A.C., Hubscher M., Henschke N., Moseley G.L., Lee H., McAuley J.H. Effect of primary care-based education on reassurance in patients with acute low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):733–743. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traeger A.C., Skinner I.W., Hubscher M., Henschke N., Moseley G.L., McAuley J.H. What you wear does not affect the credibility of your treatment: a blinded randomized controlled study. Patient Educ Couns. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Traeger A.C., Henschke N., Hubscher M. Estimating the risk of chronic pain: development and validation of a prognostic model (PICKUP) for patients with acute low back pain. PLOS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Traeger A.C., Hubscher M., Henschke N. Emotional distress drives health services overuse in patients with acute low back pain: a longitudinal observational study. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(9):2767–2773. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Traeger A.C., Moseley G.L., Hubscher M. Pain education to prevent chronic low back pain: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005505. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adriaenssens N., Coenen S., Versporten A. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): outpatient antibiotic use in Europe (1997–2009) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(suppl 6):vi3–vi12. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim S., Bosque J., Meehan J.P., Jamali A., Marder R. Increase in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: a comparison of National Surveys of Ambulatory Surgery, 1996 and 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(11):994–1000. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamdy F.C., Donovan J.L., Lane J.A. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamb S.E., Hansen Z., Lall R. Group cognitive behavioural treatment for low-back pain in primary care: a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9718):916–923. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cherkin D.C., Sherman K.J., Balderson B.H. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(12):1240–1249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H., McAuley J.H., Hubscher M., Kamper S.J., Traeger A.C., Moseley G.L. Does changing pain-related knowledge reduce pain and improve function through changes in catastrophizing? Pain. 2016;157(4):922–930. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richards D.A., Ekers D., McMillan D. Cost and Outcome of Behavioural Activation versus Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression (COBRA): a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10047):871–880. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31140-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiwa M., Millett S., Meng X., Hewitt V.M. Impact of the presence of medical equipment in images on viewers’ perceptions of the trustworthiness of an individual on-screen. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(4):e100. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moseley G.L., Arntz A. The context of a noxious stimulus affects the pain it evokes. Pain. 2007;133(1–3):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butow P.N., Lobb E.A., Meiser B., Barratt A., Tucker K.M. Psychological outcomes and risk perception after genetic testing and counselling in breast cancer: a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2003;178(2):77–81. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stacey D., Legare F., Col N.F. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:Cd001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.PICKUP Research Team. http://myback.neura.edu.au/; 2016 Accessed 22.11.16.