Highlights

-

•

A clear definition and description of the interventions in randomized controlled trials are pre-requisites for implementation in clinical practice.

-

•

There is a trend among investigators to describe control group interventions poorly compared to the experimental group.

-

•

The readers would not be able to apply the findings of the trial to their clinical practice if the interventions are poorly described.

Keywords: Physical therapy journals, CONSORT, Control group, Description of interventions

Abstract

Background

Amongst several barriers to the application of quality clinical evidence and clinical guidelines into routine daily practice, poor description of interventions reported in clinical trials has received less attention. Although some studies have investigated the completeness of descriptions of non-pharmacological interventions in randomized trials, studies that exclusively analyzed physical therapy interventions reported in published trials are scarce.

Objectives

To evaluate the quality of descriptions of interventions in both experimental and control groups in randomized controlled trials published in four core physical therapy journals.

Methods

We included all randomized controlled trials published from the Physical Therapy Journal, Journal of Physiotherapy, Clinical Rehabilitation, and Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation between June 2012 and December 2013. Each randomized controlled trial (RCT) was analyzed and coded for description of interventions using the checklist developed by Schroter et al.

Results

Out of 100 RCTs selected, only 35 RCTs (35%) fully described the interventions in both the intervention and control groups. Control group interventions were poorly described in the remaining RCTs (65%).

Conclusions

Interventions, especially in the control group, are poorly described in the clinical trials published in leading physical therapy journals. A complete description of the intervention in a published report is crucial for physical therapists to be able to use the intervention in clinical practice.

Introduction

Amongst several barriers1, 2 to the application of evidence and clinical guidelines into routine daily practice, poor description of interventions reported in clinical trials has received less attention.3 It is difficult to implement novel exercise programs like graded exposure therapy, motor imagery, and cognitive behavioral interventions without sufficient details on the components that were planned and delivered. For example, we could not implement mime therapy as part of management strategy for facial paralysis, because the information provided in clinical trials about mime therapy was inadequate.4, 5 Even for traditional interventions, such as strength or endurance training programs for clinical populations, clinicians require specific and clear details on the dosage (type of exercise, intensity, frequency, duration, and progression criteria used) provided for the study participants to carry out the treatment based on the information provided in the published reports.

Physical therapy is recognized as one of the major non-pharmacological interventions and recommended for several health conditions. Its multifaceted nature necessitates detail and accurate description to replicate. Physical therapy interventions consist of several components, such as exercise, electrical modalities, manual techniques, and education, that are applied individually or in combination. Further, care providers’ (e.g., physical therapist) skills, experience, and training can influence the outcomes of the intervention.6 Several researchers have demonstrated treatment procedures in non-pharmacological trials are often inadequately described.7, 8, 9, 10 They have pointed out that the “how to” information required by clinicians11 and consumers12 to replicate and apply in practice is missing in the majority of the studies.8, 10

A complete published description of interventions is essential for policymakers, administrators, and researchers to assess the generalizability of findings, synthesize literature, design future trials, determine the feasibility of interventions, and to develop treatment guidelines. Non-pharmacological interventions like physical therapy are complex and often contain numerous components that need elaborate reporting to replicate and apply.13, 14 Although some studies have investigated the completeness of descriptions of non-pharmacological interventions in randomized trials, studies that exclusively analyze physical therapy interventions reported in published trials are scarce.15

A recent review of physical therapy interventions15 concluded that completeness of intervention reporting in physical therapy was poor. They reviewed a random sample of 200 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in 2013 using the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist. The RCTs were retrieved from the PEDro database,16 which includes physical therapy-related RCTs published in various types of journals including those journals not indexed in Medline and without a clear editorial policy that mandates adherence to standard reporting guidelines. We hypothesized that the quality of Medline indexed journals and the editorial policy of core physical therapy journals17 would influence the standards of reporting interventions in RCTs. More studies with varying focus are necessary for a comprehensive assessment of the completeness of intervention reporting. In this study, we reviewed RCTs published in core physical therapy journals. Our aim was to evaluate the quality of descriptions of interventions in both experimental and control groups of the randomized controlled trials published in four core physical therapy journals.

Methods

In this study, we analyzed RCTs published in the four core physiotherapy journals for description of interventions using the checklist developed by Schroter et al.11 We decided to utilize the checklist by Schroter et al.11 since it not only captures major components of TIDieR,3 but also provides allowances for variations in reporting based on the nature of the underlying interventions. Physical therapy includes multifarious interventions ranging from simple to complex interventions traversing strictly mechanical interventions addressing physical problems to those addressing psychosocial domains. Currently, domain-specific checklists exist for describing interventions for individual interventions, e.g., the Guideline for Reporting Evidence-based practice Educational interventions and Teaching (GREET) checklist18 and the Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare (CReDECI 2).19 Additionally, separate intervention description checklists for behavioral interventions20 and electrotherapy interventions, such as LASER,21 are available. Lastly, many other similar, tailored checklists for manual therapy are under development (for details, refer to the Equator network for reporting guidelines). These checklists have identified a range of pointers, such as the reporting of theoretical basis, patient–provider interaction, intervention compliance, pre-evaluation findings, and dose-influencing factors that are specific to characteristics of the underlying interventions but are not currently demanded by generic checklists like the TIDieR checklist. Our pilot results identified different varieties of interventions within the journals we searched, hence we anticipated problems in using a generic and detailed but contextually less valid checklist, such as the TIDieR, utilized in a prior study for identification as opposed to using an unconstraining checklist like the one developed by Schroter et al.11 We perceived this would effectively reduce false positive results by preventing relevant reporting deficiencies and would not inadvertently discount adequate reporting. The feasibility of the TIDieR checklist in systematically describing physical therapy interventions is only currently being explored.22 van Vliet et al.22 identified few items in the TIDieR checklist as unclear and overlapping based on their recent study, which evaluated the TIDieR checklist to describe a therapy intervention used in the stroke rehabilitation trial.

Search strategy and selection of reports of trials

We selected four journals (Physical Therapy Journal [PTJ], Journal of Physiotherapy [JoP], Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation [APMR], and Clinical Rehabilitation [CR]) that we considered representative journals for published clinical trials in physical therapy. The selected journals are among the 22 journals identified by Costa et al.17 as core journals that publish physical therapy clinical trials.

Search strategy

We searched for randomized controlled trials published in the selected journals between June 2012 and December 2013. We used advanced search builder in Pubmed and performed journal-specific search using “randomized clinical trial”, “pragmatic trial”, “clinical trial”, “physiotherapy”, and “physical therapy”. Two authors also hand-searched each journal to cross-check for omissions.

We included all randomized control trials (RCTs) published in the selected journals during the period between June 2012 and December 2013. The description of physical therapy by the World Confederation of Physical Therapy's (WCPT) was used to classify the RCTs as focused on physical therapy.23 RCT protocols and studies which focused primarily on speech, drug therapy, and other behavioral therapies were excluded. A total of 176 RCTs (APMR [N = 57], CR [N = 73], JoP [N = 11], PTJ [N = 13]) were identified in accordance with our criteria.

Coding method

Each RCT was analyzed and coded for description of interventions using the checklist developed by Schroter et al.11 This checklist has seven items: setting, recipient, provider, procedure, materials, intensity and Schedule (Table 1). The items were marked as ‘Yes-if element of intervention clearly described’ or ‘No-if not adequately described’. Additionally for item procedure, materials, intensity and schedule were marked “yes” or “no” separately for the experimental group and control group. In case of trials comparing two active treatments, the second group was taken as control group. When there was more than one experimental group, the third or the last group was arbitrarily taken as control group and it was marked yes only when all the groups were adequately described. Eighth item of ‘overall’ was given ‘yes’-only if the all other items were marked ‘yes’ to denote the intervention is adequately described. In addition, we also rated “overall” separately for experimental and control group to find out if there is any change when control group was included or excluded.

Table 1.

Intervention description checklist.

| Setting | Is it clear where the intervention was delivered? | Yes/No |

| Recipient | Is it clear who is receiving the intervention? | Yes/No |

| Provider | Is it clear who delivered the intervention? | Yes/No |

| Procedure | Is the procedure (including the sequencing of the technique) of the intervention sufficiently clear to allow replication? | Yes/No |

| Materials | Are the physical or informational materials used adequately described? | Yes/No |

| Intensity | Is the dose/duration of individual sessions of the intervention clear? | Yes/No |

| Schedule | Is the schedule (interval, frequency, duration or timing) of the intervention clear? | Yes/No |

| Missing | Is there anything else missing from the description of the intervention? | Yes/No |

In the first stage, a pilot study was performed and 20 articles were randomly selected. Before coding, two authors (KH and JS) read the checklist, discussed each criterion and carried out pilot testing by independently coding each RCT using the checklist. We found substantial agreement between the two raters (κ = 0.74). Areas of disagreement were discussed again amongst the authors to achieve consensus. In the second stage, from 154 RCTs (excluding the 20 articles selected during stage 1) 100 studies were randomly selected using SPSS (version 23.0) and coded for description of interventions. Disagreements in ratings were resolved by discussion between raters.

In this study, we considered intervention reporting as complete when both control and experimental group satisfied the given criteria. Therefore, to determine the completeness of intervention, we calculated the proportion of RCTs satisfying each criteria of the checklist for both control and experimental group taken together. We also compared description of interventions for each checklist items between experimental and control groups.

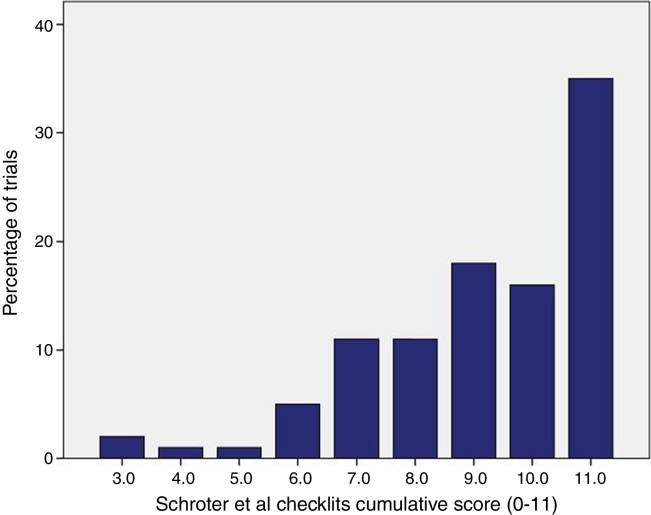

Results

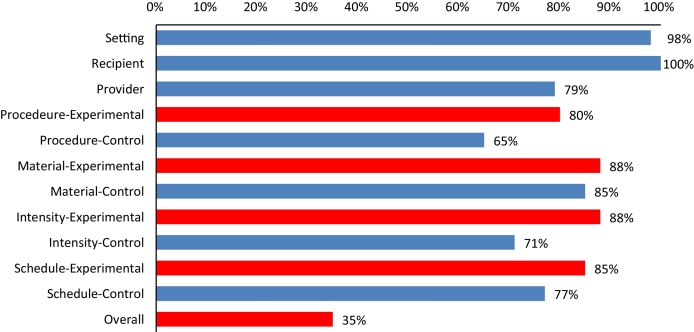

A total of 218 intervention groups were reviewed, out of which 116 as an experimental group and 102 as a control group. Out of 100 RCTs selected, only in 35 (35%) RCTs interventions are completely described for both control and experimental group, i.e., all the checklist items (11 items) were marked as “yes” (Fig. 1). Fig. 1 shows, for each of the checklist items, the percentage of interventions that were clearly described in the journal article. Control group interventions specific to the details on procedure, are described poorly (65%). Recipient (100%) and Setting (98%) were the clearly described items in the trials (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Percentages of selected clinical trials fulfilling each checklist items of Schroter et al.11

Figure 2.

Comparison of percentage of checklist items fulfilled between experimental and control group interventions.

Discussion

We aimed to investigate whether physical therapy interventions tested in clinical trials are adequately described for clinicians to implement in practice and for researchers to replicate or verify the findings. We found that the majority of the trials described physical therapy interventions inadequately. Studies did not report all information identified as essential for successful implementation in clinical practice. The majority of the studies clearly described the setting and patient characteristics, however important information regarding the procedure was unclear. We found a trend among investigators to describe control group interventions more poorly than experimental group interventions, therefore readers would not be able to apply the findings of the trial to their clinical practice.

In several studies included in our analysis, investigators used terms ‘usual or standard care’ to describe control group. This could lead to confusion as it may vary across geographic regions and treatment settings or change over time. In trials comparing an intervention to an active control or usual care, a clear description of the rationale for the comparator intervention would facilitate understanding of its appropriateness.

Although several previous studies have documented similar deficiencies in the descriptions of interventions such as patient education, music therapy, and surgery,6, 9, 10, 11 a recent study specifically analyzed the description of interventions in physical therapy trials.15 Similar to the finding of previous studies, in our study on physical therapy trials we found information about the procedure description is most commonly missing. More than half (65%) of the physical therapy RCTs included in this study has failed to describe complete information, i.e., scored “yes” for all checklist items for both control and experimental group (Fig. 2). The study by Yamato et al.,15 though similar to our study in terms of design, analyzed and only reported the completeness of interventions individually for experimental and control groups, whereas we considered intervention reporting is only complete when both groups are reported adequately in an RCT. Yamato et al. reported 75% of control groups of RCTs are incomplete, i.e., more than half of the items in the TIDieR is not reported, which is higher than our findings. The quality of the journal and the editorial policy can be potential confounders explaining poor reporting of intervention details in the RCTs. We included studies that are published in Medline-indexed, core physical therapy journals, whereas Yamato et al. retrieved RCTs from the PEDro database, which does not control for journal quality for inclusion in the database. Differences in the checklist used and having 25% of RCTs with no intervention provided to the control group in the study by Yamato et al.15 might have also contributed to the differences in the results.

Hoffmann et al.8 contacted corresponding authors as part of their study, which analyzed trials of non-pharmacological intervention. Study authors reported several reasons for not reporting details of interventions such as legal copyright restrictions and “tailored interventions so it's difficult to disseminate”. Hoffmann et al.8 further reported that comments from some authors suggested a lack of awareness of the importance of making intervention materials available. This could be one of the major reasons leading to poor description of interventions found in this study and in other previous studies too.

For the physical therapy profession to become more evidence-based, provision of sufficient details about the intervention is vital. RCTs have been exponentially growing worldwide24, 25; however, it has been suggested most of the findings are not acted upon.13 Problems encountered by clinicians in replicating the intervention due to poor description of intervention could be one of the reasons. The CONSORT statement for RCTs of non-pharmacological interventions26 has been endorsed by three journals included in this study. Only CR does not explicitly give instruction to authors on the need to follow the CONSORT guidelines. Yet, we found the majority of the articles have issues with reporting the intervention, especially in the control group. For this study, we analyzed clinical trials published only in four journals during a year; therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to trials published in other relevant physical therapy journals.

A clear definition and full description of the treatment assessed are prerequisites of therapeutic evaluation. Even for studies that conclude that an intervention is not effective, complete intervention descriptions are needed for other researchers to replicate and build on these findings. It is recognized that many scientific journals have a conventional focus on internal validity reporting, and many authors are restricted by word limits. More efficient methods of reporting in non-pharmacological treatment have been put forth, including graphic representation,27 hyperlinks to online materials (i.e., videos and intervention material),11 and a checklist8, 26 for intervention reporting. The different types of interventions can be categorized and that mode of documenting intervention can be matched. For example, interventions that introduce a novel exercise can be documented with video; behavioral interventions, with exemplars; and electrotherapy interventions, with graphic documentation of mode of application. Researchers have also come up with solutions specifically describing complex physical therapy treatment sessions13, 14 such as using a systematically developed form to record the treatment schedule with instructions and glossary of terms. These ideas can be implemented to improve the reproducibility and applicability of research findings in clinical practice. Finally, the completeness of physiotherapy intervention reporting in future publications would be greatly improved by implementing the recently developed reporting guidelines TIDieR7 and other checklists18, 19, 20, 21 developed specifically for different types of physical therapy interventions and by including a statement in the instructions to authors requiring them to make intervention protocols available when submitting intervention studies.3, 28

Conclusions

Interventions, especially in the control group, are poorly described in the clinical trials published in leading physical therapy journals. Information regarding the comparator or the control group intervention is vital for the clinicians to understand the difference and value of the experimental intervention. A complete description of the intervention in a published report is necessary for clinicians to be able to use interventions appropriately.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mr. R. Vasanthan for his significant inputs in writing an earlier version of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Silva T.M., Costa L.C.M., Costa L.O.P. Evidence-Based Practice: a survey regarding behavior, knowledge, skills, resources, opinions and perceived barriers of Brazilian physical therapists from São Paulo state. Braz J Phys Ther. 2015;19(4):294–303. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Silva T.M., Costa L., da C.M., Garcia A.N., Costa L.O.P. What do physical therapists think about evidence-based practice? A systematic review. Man Ther. 2015;20(3):388–401. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamato T., Maher C., Saragiotto B. The TIDieR checklist will benefit the physical therapy profession. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(3):191–193. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beurskens C.H., Devriese P.P., Heiningen I.V., Oostendorp R.A. The use of mime therapy as a rehabilitation method for patients with facial nerve paresis. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2004;11(5):206–210. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beurskens C.H.G., Heymans P.G. Mime therapy improves facial symmetry in people with long-term facial nerve paresis: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52(3):177–183. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(06)70026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacquier I., Boutron I., Moher D., Roy C., Ravaud P. The reporting of randomized clinical trials using a surgical intervention is in need of immediate improvement. Ann Surg. 2006;244(5):677–683. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000242707.44007.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann T.C., Glasziou P.P., Boutron I. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann T.C., Erueti C., Glasziou P.P. Poor description of non-pharmacological interventions: analysis of consecutive sample of randomised trials. BMJ. 2013;347:f3755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pino C., Boutron I., Ravaud P. Inadequate description of educational interventions in ongoing randomized controlled trials. Trials. 2012;13:63. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasziou P., Meats E., Heneghan C., Shepperd S. What is missing from descriptions of treatment in trials and reviews? BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1472–1474. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39590.732037.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroter S., Glasziou P., Heneghan C. Quality of descriptions of treatments: a review of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001978. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayo-Wilson E. Reporting implementation in randomized trials: proposed additions to the consolidated standards of reporting trials statement. Am J Public Health. 2007 Apr;97(4):630–633. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pomeroy V.M., Cooke E., Hamilton S., Whittet A., Tallis R.C. Development of a schedule of current physiotherapy treatment used to improve movement control and functional use of the lower limb after stroke: a precursor to a clinical trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2005;19(4):350–359. doi: 10.1177/1545968305280581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeJong G., Horn S.D., Gassaway J.A., Slavin M.D., Dijkers M.P. Toward a taxonomy of rehabilitation interventions: using an inductive approach to examine the “black box” of rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamato T.P., Maher C.G., Saragiotto B.T., Hoffmann T.C., Moseley A.M. How completely are physiotherapy interventions described in reports of randomised trials? Physiotherapy. 2016;102(2):121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elkins M.R., Moseley A.M., Pinto R.Z. Usage evaluation of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) among Brazilian physical therapists. Braz J Phys Ther. 2015;19(4):320–328. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa L.O.P., Moseley A.M., Sherrington C., Maher C.G., Herbert R.D., Elkins M.R. Core journals that publish clinical trials of physical therapy interventions. Phys Ther. 2010;90(11):1631–1640. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips A.C., Lewis L.K., McEvoy M.P. Development and validation of the guideline for reporting evidence-based practice educational interventions and teaching (GREET) BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:237. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Möhler R., Köpke S., Meyer G. Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2) Trials. 2015;16:204. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0709-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Des Jarlais D.C., Lyles C., Crepaz N. TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):361–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins P.A., Carroll J.D. How to report low-level laser therapy (LLLT)/photomedicine dose and beam parameters in clinical and laboratory studies. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29(12):785–787. doi: 10.1089/pho.2011.9895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Vliet P., Hunter S.M., Donaldson C., Pomeroy V. Using the TIDieR checklist to standardize the description of a functional strength training intervention for the upper limb after stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2016;40(3):203–208. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Policy statement: Description of physical therapy | World Confederation for Physical Therapy [Internet]. [cited 2014 Feb 02]. Available from: http://www.wcpt.org/policy/ps-descriptionPT.

- 24.Hariohm K., Prakash V., Saravankumar J. Quantity and quality of randomized controlled trials published by Indian physiotherapists. Perspect Clin Res. 2015;6(2):91–97. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.154007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maher C.G., Moseley A.M., Sherrington C., Elkins M.R., Herbert R.D. A description of the trials, reviews, and practice guidelines indexed in the PEDro database. Phys Ther. 2008;88(9):1068–1077. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boutron I., Moher D., Altman D.G., Schulz K.F., Ravaud P. CONSORT Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perera R., Heneghan C., Yudkin P. Graphical method for depicting randomised trials of complex interventions. BMJ. 2007;334(7585):127–129. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39045.396817.68. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Field-Fote E. Translation, implementation replication, and the documentation of interventions. J Neurol Phys Ther JNPT. 2016;40(3):163–164. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]