Abstract

Background

Suicidal behaviour is frequent in psychiatric in-patients and much staff time and resources are devoted to assessing and managing suicide risk. However, little is known about staff experiences of working with in-patients who are suicidal.

Aims

To investigate staff experiences of working with in-patients who are suicidal.

Method

Qualitative study guided by thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews with mental health staff with experience of psychiatric in-patient care.

Results

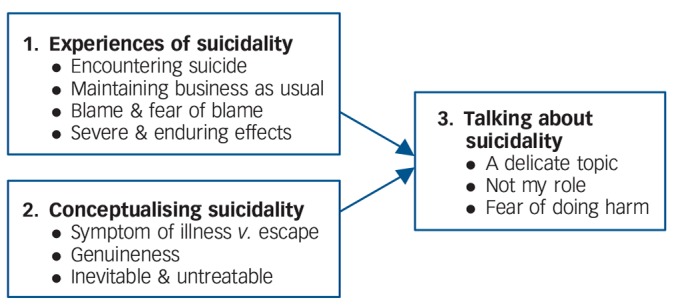

Twenty staff participated. All had encountered in-patient suicide deaths or attempts. Three key themes were identified: (a) experiences of suicidality, (b) conceptualising suicidality and (c) talking about suicide.

Conclusions

Suicidal behaviour in psychiatric wards has a large impact on staff feelings, practice and behaviour. Staff felt inadequately equipped to deal with such behaviours, with detrimental consequences for patients and themselves. Organisational support is lacking. Training and support should extend beyond risk assessment to improving staff skills in developing therapeutic interactions with in-patients who are suicidal.

The number of UK suicides has changed minimally over the past 30 years (6341 in 1983 and 6122 in 2014).1 Psychiatric in-patient suicides comprise 9% of these.2 Suicidal behaviour in psychiatric wards is common and is particularly prevalent soon after admission.3 In-patient suicides are arguably the most preventable of all because patients have continuous 24 h contact with staff,4 whose primary purpose is to maintain patient well-being.5 In-patient mental health wards are populated by patients who are acutely unwell with complex mental health needs, many of whom exhibit repetitive self-harm behaviour3 within an environment characterised by high bed occupancy, frequent staff turnover and poor staff morale.6 Staff well-being is a UK Department of Health7 priority known to present particular challenges for mental health staff and their employers.8 However, despite the stressful and demanding nature of their role5 little is known about how staff experience and perceive working with in-patients who are suicidal.9 Understanding the needs of those who work within this setting is key to maximising the opportunity to reduce suicidal behaviour. This study aimed to investigate the experiences and perceptions of staff working with in-patients who are suicidal.

Method

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 staff whose role involved working with psychiatric in-patients. This study was a component of research investigating the feasibility of delivering a novel psychological treatment for in-patients who are suicidal.10 Ethical approval was granted by a National Health Service (NHS) Research Ethics Committee (13/NW/0504).

Sampling

Participants were purposively sampled from an NHS mental health trust in Northern England. We aimed to recruit participants working with psychiatric in-patients from a range of roles and settings, thus affording maximum variance in the sample.11,12 Staff participants were recruited from ward- and community-based clinical teams following attendance at staff meetings where information about the study was offered. All participants provided written consent and were interviewed at a time and place of their choosing.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted by Y.A. or E.S.-N. following a flexible topic guide that explored participants' background experience, training to work with patients who are suicidal, understanding of mental health, suicidality and therapeutic approaches. A non-judgemental, open questioning style was adopted and participants were encouraged to introduce issues of importance not covered by the topic guide. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Identifying information was removed at transcription after which recordings were destroyed. Interviews averaged 64min duration (range 42–86). Data generation and analysis occurred in parallel using a constant comparative technique with incoming data informing subsequent interviews.11 Data collection continued until the point of theoretical saturation whereby no new relevant ideas emerged.13

Data analysis

Data were analysed using thematic analysis that offers a systematic method of identifying patterns across the data corpus.13 Initial familiarisation with the data was achieved by reading each transcript several times, followed by manual line-by-line coding and final clustering and synthesis of codes to form themes. Analysts (Y.A., S.P. and E.S.-N.) read all transcripts, with input from the wider research team who met regularly to review and discuss the evolving analysis. The team comprised academic researchers and clinicians, one of whom had personal experience of psychiatric in-patient treatment and suicidality. Drawing upon multiple researcher perspectives is advocated as a way of increasing the credibility, and therefore the trustworthiness, of the final analysis.11,12

Results

The sample included staff from a range of professions. Nursing comprised the largest group (qualified nurses n = 8; nursing assistants/support workers n = 2), followed by psychiatry (n = 4) and allied health professionals (AHP, n = 6), which included clinical psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists. Fourteen participants were female. Participants' professional experience in mental health settings ranged from 4 to 38 years.

Three themes were identified. Figure 1 illustrates how theme one (experiences of suicidality), together with theme two (conceptualising suicidality) have an impact on theme three (talking about suicide).

Fig. 1.

Thematic structure of findings.

Theme one: experiences of suicidality

Encountering suicide

All participants had encountered patients who had attempted or died by suicide. This could include direct involvement during a working shift with a current in-patient or being informed about a known patient after the event. Some also had personal experiences of attempted suicide by relatives or friends. Their descriptions of suicidal encounters were often extremely emotional and highly salient, even when the incidents had occurred several years ago. Participants reported that discovering a patient had died by suicide was not a routine clinical matter and that being told in a considerate way was important in minimising the distress experienced.

‘It's upsetting… you often hear third hand … I've come across a death by auditing case-loads and finding it had been reported on [electronic clinical records] and nobody had said … when you bring up your patient's notes that you have known for years and suddenly they're in red.’ (Psychiatrist: 17)

Maintaining business as usual

Participants described how, following an in-patient suicide, the ward atmosphere changed. Staff then had to maintain ‘usual’ ward activity, while also supporting other patients who were affected by the death and deal with their own and colleagues' feelings. Police would be present on the ward, it then being a potential crime scene. Participants reported little opportunity to pause, reflect and attempt to make sense of events within this context.

‘… we have had police activity on wards, searching, interviewing… I've just been through this, sorry … [participant becomes upset].’ (Nurse: 01)

Following a patient suicide the usual workload responsibilities of maintaining the service continued, often with little recognition of the impact of the additional professional and emotional demands on staff. Organisational support varied, some participants described formal opportunities to discuss their experiences and access additional resources, whereas others recalled little or no support being offered. This was particularly poor for senior staff, with some describing how the process of supporting junior staff after a suicide generated additional stresses.

‘I did, sort of, speak about it over supervision and just… knowing that my manager was there and she offered me support and I could access support and stuff, so… it was okay.’ (Nurse assistant/support worker: 02)

‘As for, like, me who had to deal with that, the aftermath and doing the reports about it and stuff, yet no one, spoke to me about it.’ (Nurse: 03)

Blame and fear of blame

Although some participants mentioned organisational policies purporting a ‘no blame/learning culture’, this was not always experienced.

‘So I was encouraging staff, saying, “look it's not meant about finding blame”… and actually, they were ripped to shreds in the investigation, I felt terrible… there was big blame there, um, I mean, finger-pointing.’ (Nurse: 01)

Indeed, locating ‘blame’ was often perceived as the organisational priority immediately after a suicide. Personal emotional reactions to the event were quickly superseded by concerns about impending recrimination and blame.

‘We all feel defensive when there's been a completed suicide, the first thing you do is to rack your brains to see what went wrong, erm, I talked to somebody recently about a suicide and the first thing was “What did I miss?”.’ (Psychiatrist: 17).

Participants feared being blamed for negligence with consequent loss of professional registration and livelihood as an additional burden in caring for in-patients who are suicidal.

‘It's awful but it's like well… who's to blame? … and people will be like oh God did you write that down, did you do this, did you do that? … you're looking after that person, you've got all your documentation because you've got to look after yourself and it is, it is a scary … because you know at the end of… you know you'd be sacked and you'd lose your job.’ (AHP: 10)

Severe and enduring effects

The aftermath of a patient suicide could involve prolonged distress for entire clinical teams. Staff sometimes felt excluded from investigations that could compound feeling unsupported by the organisation and further reduce opportunities to process the event and its consequences.

‘I had an incident when I was on the PICU [Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit] ward in [date] on nights that just left me absolutely, it was awful, and I was never debriefed, I was never involved in the SUI, [Serious Untoward Incident investigation] never asked what I thought, how I felt, how things could be done better.’ (Nurse: 07)

The process involved extensive investigations culminating with the coroner's hearing that usually occurred many months following the event.

‘Some girls [nurses] that were about to go to the coroner's… the team was ravaged by it. it was so toxic, they were depressed, they've been off sick, they had anxious somatic symptoms of anxiety. So it's not even just about the moment and what you do then, it goes on and on and on … and sometimes, I guess it never leaves some people, they take it with them.’ (Nurse: 01)

Theme two: conceptualising suicidality

Participants' accounts demonstrated a range of perspectives about suicidality that influenced their beliefs about effective clinical approaches and how sympathetic staff felt towards patients.

Symptom of illness v. means of escape

Participants held differing conceptual models of causes of suicidality. Several conceptualised suicidality as a symptom of an underlying psychiatric illness that should be managed with medication while protecting patients from themselves.

‘We're talking about a serotonin imbalance which causes the depression … if the person is presenting with a severe depressive episode and has suicidal ideas as part of it, erm, we then look at their antidepressant medication.’ (Psychiatrist: 11)

Others held more psychosocial conceptualisations viewing suicide as an individual's attempt to manage and escape intolerable situations, which appeared to generate more sympathy.

‘Suicide is an escape from what is going, from what is happening, they have a erm different understanding of what is going on around them or what is happening with them. They kind of sometimes catastrophise and most patients I've spoken with and are suicidal they see suicide as an escape … in one way I sympathise because some of them are very very depressed.’ (Psychiatrist: 16)

Genuineness

The authenticity of an in-patient's suicidality was frequently raised, with some participants viewing the necessity to be vigilant to this. Patients' lifestyles and social problems were judged as underlying reasons for their suicidality. Participants expressed that some patients had socially unacceptable, criminal lifestyles resulting in inappropriate use of the ward as a refuge. These patients were viewed as illegitimate users of health services attracting limited sympathy.

‘We've got a number of males who have been admitted with suicidal ideation, so they've been brought in for their own good to stop them committing suicide, but they have concurrent drug issues, they've spent all their money, they have no money left and their dealers are after them. So, it's very difficult to, well, I'd feel a bit suicidal to be honest with ya. It doesn't mean you can't man up and get on with your life.’ (Nurse: 05)

Some participants suggested that patients who frequently verbalised suicidal ideation, but did not progress to life-threatening self-harm, were not genuinely suicidal and this was sometimes viewed as manipulative.

‘Sometimes people with diagnosis, of say, personality disorder may, you know, voice suicidal ideation or wishes to end their own life … and they've not really made any serious attempts when they've had ample opportunities to do so… very tricky, tricky, tricky … sometimes it's quite challenging, you know, to pick up when people are maybe, are genuine and when people are not.’ (Nurse assistant/support worker: 04)

Suicide is inevitable and unbeatable

Past experiences of treating patients who ultimately killed themselves despite preventative efforts led some participants to develop fatalistic and defeatist attitudes towards suicide prevention.

‘There's very little you can do if somebody decides to kill themselves.’ (Psychiatrist: 16)

‘Schizophrenia, the suicide risk period is usually at point of recovery, erm, there are patients in acute psychosis who will kill themselves.’ (Psychiatrist: 17)

The frustration and hopelessness experienced when extensive efforts to support patients who repeatedly self-harmed were exhausted and ineffective led some staff to question their ability to help suicidal patients.

‘Cause if you get a client… that's got repeated suicidal ideation and that's repeating in trying to harm themselves… you can get to a stage when you think “I've tried it, I don't know what to do anymore, I've tried everything, I don't know whether what I'm doing is useful or whether ifs making it worse”.’ (Nurse: 03)

Theme three: talking about suicide

Together these experiences and beliefs influenced a reluctance to talk with patients about their suicidality. Conversations could be difficult and participants feared causing further distress. Moreover, some felt it was beyond their remit, particularly those with more direct patient contact.

A delicate topic

The topic of suicidality, even in in-patient settings where participants frequently encountered suicidal patients, was viewed as a delicate one. Participants expressed uncertainty about how to initiate and conduct useful conversations that would not cause further distress.

‘Should I ask? Shouldn't I ask? What kind of question should I ask? What kind of question shouldn't I ask?’ (AHP: 08)

Participants used euphemistic language (‘oh, well, you know, if you're not feeling right.’ (Nurse assistant/support worker: 02)) avoiding overt discussion about suicide. Distraction was also used to divert patients from talking about their suicidal feelings.

‘So usually during the course of conversation if someone says “I'm suicidal, I'm gonna die, I'm gonna do this” and then you kinda like… talk about something else… then say “oh, you're going on holiday next year?”, “you're doing something over the summer?”.’ (Nurse: 05)

There was a suggestion that avoidance of talking explicitly about suicide was reinforced within ward culture.

‘Everyone was like “you can't say words like that!” and I was like “well, I can say words like that”, because we're people and we're professional services. So I think, learning how to say those words, you know, “if you want to kill yourself, or if you're attempting suicide”, sometimes being stark about it is actually beneficial because I think … ifs putting a situation into reality.’ (Nurse assistant/support worker: 02)

Not my role to talk about suicide

Participants questioned whether it was their role to talk about suicide with in-patients, seeing it as the responsibility of others. This was partly attributed to lack of formal training and supervision.

‘I haven't had any specific training in dealing with [suicidal patients] because that wouldn't be my role to kind of, ehm, do that.’ (AHP: 09)

‘You know that you're going to have suicide risk but you think well, the psychologists will deal with that bit… so to want to deal with it, even as part of the overall care, I think you'd want some type of supervision…I think without that, I think you, you would feel like am I qualified to do this? Am I qualified enough?’ (AHP: 10)

Furthermore, some voiced that the responsibility for disclosing suicidal thoughts lay with the patient; hence it was not their role to initiate such conversations.

‘Basically, ifs down to them to tell us … we've no other way really unless they already told their relative so they're gonna have to be speaking about it.’ (Nurse: 05)

Where participants did feel they had a remit to explore and discuss suicidal thoughts with patients, most felt supervision was needed. Those who accessed supervision viewed it as beneficial, however others, even when available, did not view it as fundamental to routine clinical practice.

‘As someone that actually has clinical supervision I find it really quite helpful, so that's why I encourage people to go… I mean if you're a member of a profession I think you should take responsibility for your own development and progression and, and needs really.’ (Nurse: 03)

‘It's a historical thing. We never used to bother it was always “well, why do I need to talk about it?” … the excuse is always about time and space but, you know, we've got ways of working around that, if we want to do. There is no formal expectation that nurses get supervision in order to practice… it might be guided and recommended … but that's it… then what you get is a flurry of activity when people are really in crisis, really struggling … by the time they're saying “I need supervision, I need it quick”, ifs possibly a bit late. You know, they don't see it as things that sustains you, and maintains you, ifs just something that rescues you, sort of, you know, in a difficult time.’ (Nurse: 01)

More commonly, participants made their own arrangements for informal support from colleagues, friends or family to discuss experiences of working with in-patients who are suicidal.

Fear of causing harm

Participants were concerned about the potential to cause harm by discussing suicidality with patients which could inhibit such conversations. This view, though common, was not ubiquitous and some senior staff felt encouraging patients to talk about their distress was valuable.

‘I don't think it erm it negatively impacts on a patient… in fact, erm being more open and bringing that, you know, bring those words into the conversation makes it real and makes it easier for the patient to talk about it.’ (Psychiatrist: 11)

Nevertheless, staff were preoccupied with the need for detailed documentation to exonerate themselves of negligence should a suicide occur. This led to cautious and guarded conversations in case patients would reveal suicidal thoughts.

‘It can make them [staff] very risk-averse, it makes people defensive, not defensible… They will constantly exercise on the side of caution … to the detriment of the patient really… where they are actually almost inert… they're just… frozen.’ (Nurse: 01)

In particular, it was recognised that the vast majority of opportunities for interactions occurred with junior staff who were the most fearful of causing harm to patients and of consequences for themselves.

‘I think ifs scary because you don't want to be the last person having that conversation and they do something. You don't want to think you've done anything that could have erm, actually aggravated them or tipped them over the edge or you've said something that has made them think about something.’ (AHP: 10)

Discussion

Summary of findings

Staff working with psychiatric in-patients frequently encounter suicide. These experiences transcend all levels of seniority, have an impact both professionally and personally, with long-lasting effect. Dealing with the aftermath of events occurs alongside, and has an impact on, ongoing clinical practice.

Staff varied in their conceptualisations of suicidality. For some, their beliefs led them to question the legitimacy of patients' needs. Moreover, suicidality was seen by some as an inevitable feature of mental illness being essentially untreatable. These views influenced care, creating reluctance to initiate or pursue discussions with patients about suicidality. Junior staff, with the least training or opportunities for clinical supervision, spend the most time with patients, but felt that engaging in conversations about distress and suicidality was beyond their remit, might harm the patient and leave themselves professionally and personally vulnerable. Together these factors of high job demands, low autonomy and poor support may contribute to low staff morale recognised to be common in psychiatric ward staff.14

Comparisons with wider literature

The impact of bereavement by suicide has been described as a ‘tsunami’.15 Our findings confirm previous research where staff identified sadness, blame, low morale and inadequate support.14,16 Although literature on the impact of patient suicide on professionals also describes anger as an emotional response,17 our findings suggest that this was only expressed when talking about descriptions of their experiences of institutional reactions. It is possible that the questions used in our interviews might not have been sufficiently probing in this area, and this may be a limitation. Such perceptions potentially further compound the emotional trauma following a patient death by suicide. Indeed, the stress of being investigated after a serious incident has been cited in relation to ‘second victim’ clinician suicides.18 Organisations therefore, should consider how suicide events are managed and staff supported during the often lengthy investigations. Senior staff who had additional responsibilities for supporting junior staff following a suicide were the least supported in these situations.

An important finding is how the range of staff beliefs about suicidality had an impact on attitudes to patients and how this influenced patient care. For example, conceptualising suicidality as part of an illness resulted in some staff not addressing suicidality directly but in treating the underlying illness. Some staff viewed suicidality as an inevitable (and hence untreatable) feature of a condition. In contrast, a psychological conceptualisation that viewed suicidality as a response to modifiable thoughts resulted in more positive approaches and greater optimism for intervention. Where suicidality was perceived to result from an individual's ‘life choices’ and behaviours, such as illicit drug-taking, staff queried patients' legitimacy as healthcare users and were reluctant to engage with them. Hence, our findings indicate the potential that staff education towards more idiosyncratic and holistic conceptualisations of suicidality could counter fatalistic approaches to care.

Some staff feared that discussing suicidality with patients could create further distress making the patient worse. Concerns about discussing suicide with patients were also influenced by fears that, should a suicide occur, clinical records would be scrutinised identifying them as the last person to speak with a patient before the event. Further, that this would be investigated within a perceived ‘blame-seeking’ culture leaving them professionally vulnerable. In contrast, the evidence indicates that providing an opportunity to talk is clinically relevant19–22 and welcomed by patients as helpful in making sense of their situation.23,24

Avoidance behaviours may be particularly prevalent when staff resources are low and risk management procedure takes priority. For example, Bowers et al16 found that, faced with excess ward pressure, staff resort to increased use of risk-management practices including formal observation which, despite being enshrined in policy, has been criticised for how staff implement the procedural, but not the therapeutic engagement, ideals of observation.22 The irony is that it is often the more junior support staff, with least training, who have most direct contact with patients,25 and hence most opportunity to interact with them. We found staff often resorted to distraction and avoided talking about suicide with patients thereby missing potentially valuable contact opportunities.

Clinical supervision can help staff to reflect, understand and challenge unhelpful responses to patients, which improves therapeutic interactions.26 However, this was largely inaccessible to staff, or seen as unnecessary and only accessed in times of crisis. Research exploring in-patient nurses' views of clinical supervision similarly identifies a culture of passive-resistance fuelled by the concern that engaging in clinical supervision would imply weakness or poor coping.6 Developing a better understanding of the value of clinical supervision as a routine, rather than reactive, practice holds promise but requires organisational support.

Developing effective relationships is fundamental for safe and supportive care of suicidal patients.21 A non-judgemental accepting approach is essential to facilitate engagement with individuals who are suicidal.27 However, our findings revealed several factors operating within in-patient settings that prevent or reduce opportunities for therapeutic interactions. Staff perceptions of professional vulnerability, feeling unsupported, questioning the legitimacy of patients care needs, and concerns about causing harm, led staff to avoid conversations about suicide with patients. Staff training should therefore focus on developing greater understanding of the psychosocial factors that contribute to suicidality and the value of enabling patients to communicate their distress.20

Training should extend beyond procedural aspects of completing risk assessment forms. Evidence suggests that most patients who died by suicide had been assessed as ‘no or low-risk’22 demonstrating inadequate and unsafe predictive validity of commonly used ‘tick-box’ forms. These have been discredited by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence who recommend formulation-based psychosocial assessment conducted collaboratively with the patient.28 Patients who received a psychosocial assessment had 40% reduction in repetition of self-harm over the ensuing 12 months.29 Our study indicates that staff would require broader understandings of suicidality and communication skills to facilitate the frank discussions necessary to conduct formulation-based psychosocial assessment.28

Strengths and limitations

Our sample comprised mental health staff from a range of professions and roles, within which it is likely that different attitudes prevail. The limited numbers of participants in specific professional groups prohibited any analysis of differences in beliefs and attitudes between professions and roles, however, this would be an area for further investigation. The study setting comprised one NHS trust serving a population with high levels of socioeconomic deprivation and mental health morbidity with one of the highest suicide rates in UK, 2 consequently staff experiences may be different elsewhere. It is possible that some participants may have been concerned about disclosing such sensitive information during the interviews although the richness of data obtained suggests that this was unlikely to have been so. In this study participants mainly talked about patient suicides, there may be differences in how staff experience and perceive suicide attempts compared with actual suicides.

Clinical and research recommendations

Several recommendations for clinical practice and training arise from the study, which is summarised in the Appendix. Specifically, organisational strategies should support cultural change recognising the emotional labour of caring for patients who are suicidal by actively encouraging staff uptake of training and clinical supervision. Treatment protocols for the care of patients who are suicidal should prioritise proactive therapeutic communication interventions.28

Further research is required to understand the impact of organisational culture and context on staff perceptions of suicidality and clinical interactions. Participatory methodologies enabling active staff involvement in the research process may help determine how best to intervene to create effective change. Larger studies are required to investigate whether profession or role-specific training interventions would be more effective. Normalisation of new initiatives (such as clinical supervision and psychosocial formulation) is crucial to ensure uptake and implementation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of this study who provided accounts of the realities of their everyday working life by generously sharing some very personal and often traumatic experiences, we are grateful to members of our Service User Reference Group (INSURG) who provided advice throughout the study and to Stockport and District Mind and the Samaritans who provided further consultation. We are also grateful to Isabelle Hunt for comments on an early draft.

Appendix

Implications and recommendations

| Staff experience and perception | Implications for staff, patients and clinical practice | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Repeated exposure to suicidality | Normalisation of suicidality (acclimatisation, blunting of empathic capacity) Emotional toll on staff (burnout and reduced morale, sickness absence, high staff turnover, reduced stability of ward teams, increased National Health Service recruitment costs) |

Structured peer support to create culture of support Mandatory clinical supervision to allow staff time to reflect and receive support in developing personal resilience and self-care strategies Support for staff at all levels of seniority following serious incidents (for example patient death/serious attempt) |

| Organisational blame | Staff fear negative impact on career/livelihood Increased risk-aversive practices Training limited to mandatory organisational risk assessment/management procedures |

Organisational strategy/culture shift towards a genuine ‘no blame’/learning organisation Active encouragement of staff to uptake support resources (training and supervision) Involvement of staff in investigations Protocols for ensuring that staff are supporting following an event |

| Conceptualising suicide as inevitable and untreatable |

Management options viewed as limited Learned helplessness by staff |

Training in (a) broader holistic models of suicidality and (b) formulation-based psychosocial assessment Wards to have access to effective psychological interventions for in-patients who are suicidal |

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

Y.A. is a trustee for a North-west England branch of the charity Mind.

Funding

This research was funded by NIHR Research for Patient Benefit programme (PB-PG-111–26026).

References

- 1. Office for National Statistics Statistical Bulletin: Suicides in the United Kingdom: 2014 Registrations. ONS, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. National confidential inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCISH) Annual Report: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and wales, university of Manchester, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stewart D, Ross J, Watson C, James K, Bowers L. Patient characteristics and behaviours associated with self-harm and attempted suicide in acute psychiatric wards. J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 1104–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Appleby L, Shaw J, Kapur N, Windfuhr K, Ashton A, Swinson N, et al. Avoidable Deaths: Five-year Report of the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCISH). University of Manchester, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowers L, Banda T, Nijman H. Suicide inside. A systematic review of inpatient suicides. J Nerv Ment Dis 2010: 198: 315–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cleary M, Hunt G, Horsfall J, Deacon M. Ethnographic research into nursing in acute mental health units: a review. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2011; 32: 424–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Department of Health NHS Staff Health and wellbeing: Final Report Department of Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson S, Osborn D, Araya R, Wearn E, Paul M, Stafford M, et al. Morale in the English mental health workforce: questionnaire survey. Br J Psychiatry 2012; 201: 239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cutcliffe J, Stevenson C. Feeling our way in the dark: the psychiatric nursing care of suicidal people – a literature review. Int J Nurs Studies 2008: 45: 942–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haddock G, Davies L, Evans E, Emsley R, Gooding P, Heaney L, et al. A study to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of a cognitive behavioural suicide prevention therapy for people in acute psychiatric wards: the rationale and design of the ‘INSITE’ randomised control trial. Trials 2016; 17: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peters S. Qualitative research methods in mental health. Evid Based Ment Health 2010; 13: 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tracey S. Qualitative quality: Eight “Big tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual Inq 16: 837–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jenkins R, Elliott P. Stressors, burnout and social support: nurses in acute mental health settings. J Adv Nurs 2014; 48: 622–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grad O. The sequelae of suicide: survivors. In International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice (eds O'Connor R, Platt S, Gordon J.): 561–76. Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bowers L, Simpson A, Eyres S, Nijman H, Hall C, Grange A, et al. Serious untoward incidents and their aftermath in acute inpatient psychiatry: the Tompkins Acute Ward Study. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2006; 15: 226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wurst F, Mueller S, Petitjean S, Euler S, Thon N, Wiesbeck G. Patient suicide: a survey of therapist's reactions. Suicide and Life-Threat Behav 2010; 40: 328–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strobl J, Panesar S, Carson-Stevens A, Mclldowie B, Ward H, Cross H, et al. Suicide by Clinicians involved in Serious Incidents in the NHS: A Situational Analysis. Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust Clinical Leaders Network, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bowles N, Dodds P, Hackney D, Sunderland C, Thomas P. Formal observations and engagement: a discussion paper. J Psychiatr Ment Health 2002; 9: 255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cole-King A, Green G, Gask L, Hines K, Platt S. Suicide mitigation: a compassionate approach to suicide prevention. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2013; 19: 276–83. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gilburt H, Rose D, Slade M. The importance of relationships in mental health care: a qualitative study of service users' experiences of psychiatric hospital admission in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res 2008; 8: 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCISH) In-patient Suicide Under Observation. University of Manchester, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mind Listening to Experience: An Independent Inquiry into Acute and Crisis Mental healthcare. Mind Publications, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taylor PJ, Awenat Y, Gooding P, Johnson J, Pratt D, Wood A, et al. The subjective experience of participation in schizophrenia research: a practical and ethical issue. J Nerv Ment Dis 2010; 198: 343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bee P, Richards D, Loftus P, Baker J, Bailey L, Lovell K, et al. Mapping nursing activity in acute inpatient mental healthcare settings. J Ment Health 2006; 15: 217–26. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cleary M, Freeman A. The cultural realities of clinical supervision in an acute inpatient mental health setting. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2015; 25: 489–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tarrier N, Kelly J, Gooding P, Pratt D, Awenat Y, Maxwell J. Cognitive Behavioural Prevention of Suicide in Psychosis: A Treatment Manual. Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28. National institute for Health and care Excellence Self-Harm: Longer-Term Management (CG133). NICE, 2011. (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG133). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kapur N, Stegg S, Turnbull P, Webb R, Bergen H, Hawton K, et al. Hospital management of suicidal behaviour and subsequent mortality: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2015; 2: 809–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]