Abstract

Existing metagenome datasets from many different environments contain untapped potential for understanding metabolic pathways and their biological impact. Our interest lies in the formation of trimethylamine (TMA), a key metabolite in both human health and climate change. Here, we focus on bacterial degradation pathways for choline, carnitine, glycine betaine and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) to TMA in human gut and marine metagenomes. We found the TMAO reductase pathway was the most prevalent pathway in both environments. Proteobacteria were found to contribute the majority of the TMAO reductase pathway sequences, except in the stressed gut, where Actinobacteria dominated. Interestingly, in the human gut metagenomes, a high proportion of the Proteobacteria hits were accounted for by the genera Klebsiella and Escherichia. Furthermore Klebsiella and Escherichia harboured three of the four potential TMA-production pathways (choline, carnitine and TMAO), suggesting they have a key role in TMA cycling in the human gut. In addition to the intensive TMAO–TMA cycling in the marine environment, our data suggest that carnitine-to-TMA transformation plays an overlooked role in aerobic marine surface waters, whereas choline-to-TMA transformation is important in anaerobic marine sediments. Our study provides new insights into the potential key microbes and metabolic pathways for TMA formation in two contrasting environments.

Keywords: Trimethylamine, Marine, gut microbiome, metagenome

Data Summary

The metagenomes examined in this study were downloaded from CAMERA (now iMicrobe) and MG-RAST [Data citation 1–22] detailed in Table S1.

Impact Statement

In this study we used the existing wealth of metagenome data to answer the question ‘which bacterial metabolic pathways are important in producing trimethylamine (TMA)?’ TMA has recently been demonstrated to play a vital role in both human health (linked to heart disease) and climate change (being a climate-active trace gas and precursor of the greenhouse gas methane). Previous studies have shown that both gut and marine sediment bacteria are capable of producing TMA, but no existing studies have looked at which bacterial genera or metabolic pathways contribute most. To this end we concentrated on two environments, where TMA-production has a critical impact, the human gut and marine environments. TMA is produced directly from choline, carnitine, glycine betaine (GBT) and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO). Our analysis of both the human gut and marine environments revealed that the previously overlooked TMAO–TMA pathway was the most abundant, by utilizing a combination of blast and profile-HMM gene similarity searches of metagenome datasets. Our data indicate that the TMAO–TMA pathway has the greatest therapeutic potential as a target for improving human health and mitigating climate change.

Introduction

In the last decade, meta-omics research has generated a wealth of data on the composition of microbial communities from diverse environments. We sought to use these data to analyze the distribution of microbial trimethylamine (TMA) formation pathways. In the human gut, TMA formation from choline and carnitine is linked to cardiovascular disease (CVD); through the hepatic formation of the proatherosclerosis compound, trimethylamine N-oxide [TMAO; (Wang et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2016; Koeth et al., 2013)]. TMA also plays an essential role in marine ecosystems, being a major precursor (35–90 %) of the greenhouse gas methane in coastal sediments (King, 1984), and a major carbon and energy source in surface waters for the marine heterotroph clades of Roseobacter and SAR11 (Lidbury et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2011). Although these disparate environments exhibit many fundamental differences, both the marine and human gut environments are subject to high osmotic stress. Furthermore marine sediments share low oxygen and high productivity with the gut. Whilst several marine sediment studies have evaluated which microbial species are involved in TMA formation (King, 1984, 1988), species information for gut TMA formation is lacking. Microorganisms in both marine and gut environments play essential roles in quaternary amine cycling and TMA-production, yet our understanding of the key microbes needs resolving. It leads us to ask which microorganisms and precursor molecules are key to TMA-production in these two contrasting ecosystems?

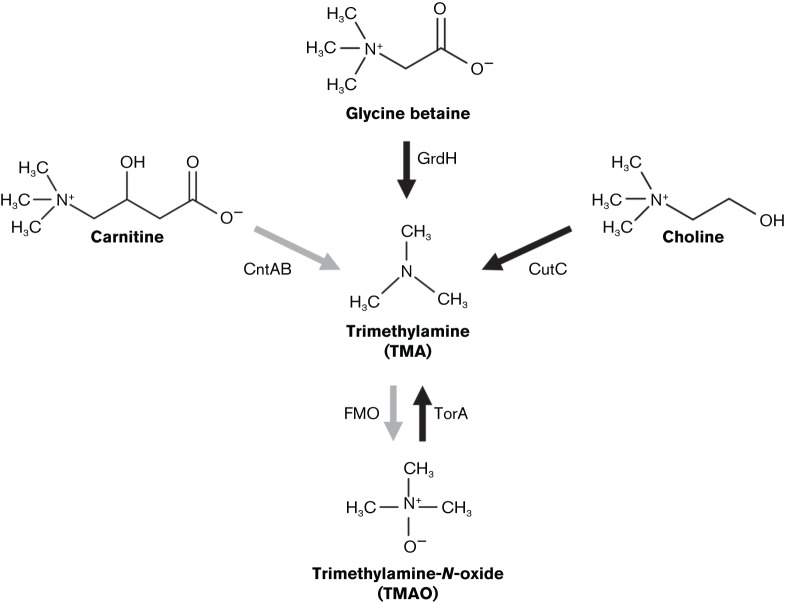

Several pathways for TMA formation are currently known (Fig. 1), involving choline–TMA lyase, CutC (Craciun & Balskus, 2012; Jameson et al., 2015), carnitine monooxygenase, CntAB (Zhu et al., 2014), glycine betaine (GBT) reductase, GrdH (Andreesen, 1994), and additionally via the reduction of TMAO, TorA/TorZ/DorA (hereafter referred to as TorA; Méjean et al., 1994; McCrindle et al., 2005). Here we investigate the abundance of potential TMA-production pathways, through targeted datamining of human gut and marine metagenomes, offering new insights into the potential major precursors and key microbial players in TMA formation in these contrasting environments.

Fig. 1.

Direct formation pathways of trimethylamine (TMA). Genes encoding the key enzymes indicated were targeted for the data-mining. Key enzymes: CntAB, carnitine monooxygenase (Zhu et al., 2014); CutC, choline-TMA lyase (Craciun & Balskus, 2012); GrdH, glycine betaine reductase (Andreesen, 1994); TorA, trimethylamine N-oxide reductase (Méjean et al., 1994). Additionally the TMAO formation pathway FMO (flavin-containing monooxygenase) is indicated as it is critical to TMA cycling (Chen et al., 2011). Black arrows denote anaerobic pathways and grey arrows denote aerobic pathways.

Methods

We retrieved 9 human gut and 13 marine metagenome studies, comprising 221 datasets from public databases (Table S1, available in the online Supplementary Material), selected for their depth of coverage, in environments where TMA is important. The gut metagenomes were divided into “stressed” (ICU patient, pregnancy and extreme aging) and “healthy” (variety of diets, no reported illnesses). We combined blast and profile Hidden Markov Models (profile-HMM) methods to determine the abundance of potential TMA pathway genes. The blastp searches were conducted using blast+ (NCBI) with a single representative protein sequence query (Fig. S1, available in the online Supplementary Material), with an E-value cut off of 1×10−5. The representative protein sequence queries were selected because they had proven functions. The profile-HMMs used representative protein alignments of 10–30 reference sequences (Fig. S1) spanning each key TMA-pathway protein (Fig. 1). HMM-based metagenomic searches and taxonomic annotations were performed using the MetAnnotate pipeline (Petrenko et al., 2015) with default parameters. Searches were performed using hmmsearch (HMMER 3.1b1) and USEARCH (Edgar, 2010) was used for best-hit classification, against the NCBI RefSeq database. Profile-HMMs attempted to negate the bias inherent in single sequence blast queries (Eddy, 2011). The resultant hits from both methods were used by MUSCLE 3.5 (Edgar, 2004) to build multiple protein alignments, then maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., 2010). Phylogenetic mapping of these hit sequences against reference datasets (Fig. S1) allowed validation of the results with false-positive hits rejected. Positive hits were normalized to gene length.

Results and Discussion

Human gut

Results of previous studies have indicated that choline is the major precursor of TMA in the gut (Wang et al., 2011; Craciun & Balskus, 2012; Tang et al., 2013; Martínez-del Campo et al., 2015; Ierardi et al., 2015; Romano et al., 2015). Our results support the idea of choline as the most important dietary contributor to TMA-production (e.g. higher than GrdH or CntA), however the TMAO (TorA-like) pathway had the highest detection rate. This high TorA-like abundance cannot be accounted for solely by dietary intake because TMAO is restricted primarily to marine fish (Mackay et al., 2011; Svensson et al., 1994). Alternatively we suggest an intensive cycling between TMA and TMAO within the gut environment, with TMAO being an important alternative electron receptor for anaerobic respiration by facultative gut microbiota (Winter et al., 2013).

The glycine betaine (GrdH) pathway was detected at relatively low levels, which may be attributed to its requirement for the trace element, selenium, for enzyme activity (Freudenberg et al., 1989). Clinical studies found a link between low plasma concentrations of selenium and CVD, while selenium supplementation trials did not improve outcomes (Flores-Mateo et al., 2006; Fairweather-Tait et al., 2011); potentially indicating a selenium requirement by a CVD-inducing GrdH containing bacterial community (Freudenberg et al., 1989). It is also likely that low abundance of GrdH in the gut metagenome was due to GBTs importance as a compatible solute. Accumulation of compatible solutes is necessary to combat stresses in the small intestine, such as volatile fatty acids, bile salts, high osmolarity and low oxygen (Sleator & Hill, 2002; Beumer et al., 1994). De novo synthesis of compatible solutes, e.g. GBT and carnitine, are generally energy-expensive, therefore, their catabolism is likely to be rare in the gut, compounding the scarcity of the GrdH-like and CntA-like pathways. Additionally, the limited oxygen availability in the gut may contribute to the low abundance of the O2-dependent CntA pathway (Zhu et al., 2014).

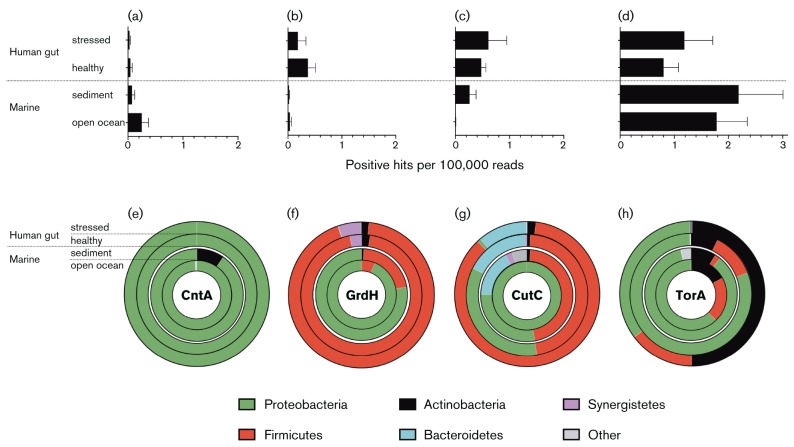

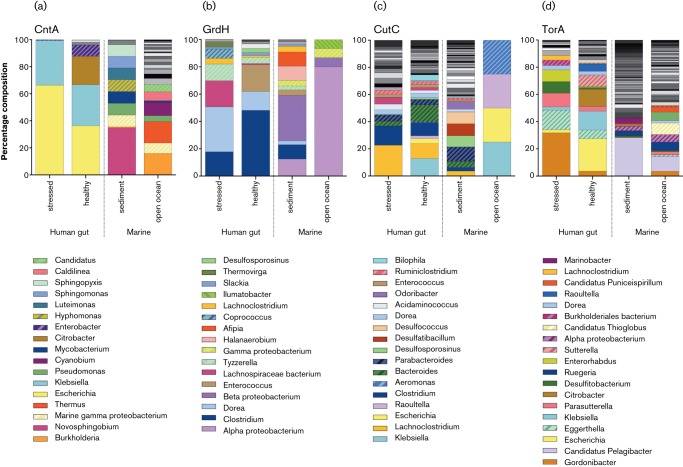

The positive hits for the CntA and GrdH pathways were both dominated by single phyla, Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, respectively (Fig. 2e, f); however, key phylogenetic variations were observed between stressed and healthy gut datasets in CutC and TorA (Fig. 2g, h). For CutC 46 % hits were Firmicutes in the healthy gut, rising to 86 % in stressed datasets (Fig. 2g) whereas for TorA hits, Actinobacteria rose from 7 % in the healthy gut to 50 % in the stressed gut (Fig. 2h). Notably, at the genus level (Fig. 3), Klebsiella and Escherichia harboured three of the four potential TMA-production pathways, accounting for approximately 13 % and 4 % of CutC, approximately 30 % and 36 % of CntA and approximately 14 % and 24 % TorA in the healthy and stressed datasets, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Data-mining of TMA pathway positive hits, combined blastp and profile-HMM searches of human gut and marine metagenomes. (a–d) represent positive, phylogenetically confirmed hits, normalized to gene length (CntA, 1116 bp; GrdH, 1314 bp; CutC, 3432 bp; TorA, 2529 bp). Error bars represent sem. Bar charts (a–d) represent relative abundance of hits: (a), CntA; (b), GrdH; (c), CutC; (d), TorA. Donut charts (e–h) shown the relative abundance (per 100 000 reads) of phylum-level classification of sequences obtained from blastp and profile-HMMs combined: (e), CntA; (f), GrdH; (g), CutC; (h), TorA. The outer rings represent stressed human gut (32 datasets); the second rings, represent healthy human gut (135 datasets); the third rings marine sediment (36 datasets) and the inner rings open ocean metagenomes (18 datasets; details in Table S1).

Fig. 3.

Bar charts depicting the genus-level assignments for confirmed hits. These illustrate relative percentage abundances of phylogenetically confirmed sequence hits at genus-level classification for sequences obtained from both blastp and profile-HMM combined.

Marine

Paralleling the results from the gut, there was a high prevalence of TorA hits in the marine datasets indicating that TMAO also has a pivotal role in marine TMA cycling (Fig. 2a–d). This was somewhat surprising in the open-ocean since TMAO reduction is primarily considered an anaerobic pathway; however, the TorA enzyme has been shown to be active under aerobic conditions (Ansaldi et al., 2007). TMAO formation from TMA can be attributed to widespread flavin-containing monooxygenase activity (Fig. 1) in a variety of marine biota (Chen et al., 2011; Gibb & Hatton, 2004). As theorised for the gut, intensive TMA–TMAO cycling may also be important in marine systems.

The next most abundant TMA-production pathway varied between the marine sediment and open ocean datasets (Fig. 2). There appears to be a level of mutual exclusivity between the potential CntA- and CutC-pathways related to oxygen requirement, resulting in higher abundance of the CntA-like pathway in the aerobic open ocean and conversely the CutC-like pathway is more prevalent in anaerobic sediments (Fig. 2a–c).

The GrdH-like pathway was detected at the lowest abundances in the marine datasets, as described for the gut, and this could indicate the importance of GBT as a key compatible solute for marine microorganisms (Andreesen, 1994; Andreesen et al., 1999).

Phylogenetically, all four genes showed dominance by Proteobacteria in the marine datasets, however Firmicutes made a significant contribution to GrdH- and CutC-hits in sediments and TorA-hits in open ocean datasets. At the genus level (Fig. 3), numerous diverse genera were detected, resulting in no notable overlaps of dominant genera between marine datasets, which is hardly surprisingly since sediments and the open oceans have distinct environmental characteristics.

Conclusion

Our quantitative analyses of genes encoding TMA formation pathways in contrasting ecosystems imply that the TMAO reduction (TorA) pathway was the most prevalent TMA formation pathway in both the marine and gut environments, indicating intensive cycling between TMAO and TMA. These TorA-like enzymes have previously been detected in the human gut (Ravcheev & Thiele, 2014) and the marine environment (Dos Santos et al., 1998), but this cycle has been overlooked in TMA-related CVD studies (Tang & Hazen, 2014). With regard to diet-derived TMA, our results corroborate findings that choline is the most important dietary component (compared with GBT and carnitine), because CutC was the most abundant pathway for TMA formation in the gut. The anaerobic GrdH-like and aerobic CntA-like pathways were detected at the lowest levels across the environments, potentially due to their roles as compatible solutes (Andreesen et al., 1999; Beumer et al., 1994). The gut is largely anaerobic and this appeared to be reflected in the higher prevalence of the anaerobic pathways (TorA, CutC, GrdH). In the marine datasets, we split the metagenomes into low-oxygen sediments and high-oxygen open ocean, and these analyses suggest some mutual exclusion between oxygen-dependent carnitine and oxygen-free choline transformation to TMA.

Supplementary Data

Abbreviations:

- FMO

flavin-containing monooxygenase

- TMAO

trimethylamine N-oxide

- GBT

glycine betaine

- HMM

Hidden Markov Models

- TMA

trimethylamine

References

- Andreesen J. R.(1994). Glycine metabolism in anaerobes. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 66223–237. 10.1007/BF00871641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreesen J. R., Wagner M., Sonntag D., Kohlstock M., Harms C., Gursinsky T., Jäger J., Parther T., Kabisch U., et al. (1999). Various functions of selenols and thiols in anaerobic Gram-positive, amino acids-utilizing bacteria. Biofactors 10263–270. 10.1002/biof.5520100226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansaldi M., Théraulaz L., Baraquet C., Panis G., Méjean V.(2007). Aerobic TMAO respiration in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 66484–494. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05936.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beumer R. R., Te Giffel M. C., Cox L. J., Rombouts F. M., Abee T.(1994). Effect of exogenous proline, betaine, and carnitine on growth of Listeria monocytogenes in a minimal medium. Appl Environ Microbiol 601359–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Patel N. A., Crombie A., Scrivens J. H., Murrell J. C.(2011). Bacterial flavin-containing monooxygenase is trimethylamine monooxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci 10817791–17796. 10.1073/pnas.1112928108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciun S., Balskus E. P.(2012). Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci 10921307–21312. 10.1073/pnas.1215689109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos J. P., Iobbi-Nivol C., Couillault C., Giordano G., Méjean V.(1998). Molecular analysis of the trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) reductase respiratory system from a Shewanella species. J Mol Biol 284421–433. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy S. R.(2011). Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput Biol 7e1002195. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C.(2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 321792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C.(2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than blast. Bioinformatics 262460–2461. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairweather-Tait S. J., Bao Y., Broadley M. R., Collings R., Ford D., Hesketh J. E., Hurst R.(2011). Selenium in human health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 141337–1383. 10.1089/ars.2010.3275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Mateo G., Navas-Acien A., Pastor-Barriuso R., Guallar E.(2006). Selenium and coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 84762–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg W., Hormann K., Rieth M., Andreesen J.(1989). Involvement of a selenoprotein in glycine, sarcosine, and betaine reduction by Eubacterium acidaminophilum. Selenium in Biology and Medicine. 25–28. Edited by Wendel A.Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb S. W., Hatton A. D.(2004). The occurrence and distribution of trimethylamine-N-oxide in Antarctic coastal waters. Marine Chemistry 9165–75. 10.1016/j.marchem.2004.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J.-F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O.(2010). New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic biology. 59307–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ierardi E., Sorrentino C., Principi M., Giorgio F., Losurdo G., Di leo A.(2015). Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine: a novel insight in the cardiovascular risk scenario. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 4289–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson E., Fu T., Brown I. R., Paszkiewicz K., Purdy K. J., Frank S., Chen Y.(2015). Anaerobic choline metabolism in microcompartments promotes growth and swarming of Proteus mirabilis. Environ Microbiol. 10.1111/1462-2920.13059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G. M.(1984). Metabolism of trimethylamine, choline, and glycine betaine by sulfate-reducing and methanogenic bacteria in marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 48719–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G. M.(1988). Distribution and metabolism of quaternary amines in marine sediments. Nitrogen Cycling in Coastal Marine Environments, 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- Koeth R. A., Wang Z., Levison B. S., Buffa J. A., Org E., Sheehy B. T., Britt E. B., Fu X., Wu Y., et al. (2013). Intestinal microbiota metabolism of l-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med 19576–585. 10.1038/nm.3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidbury I. D., Murrell J. C., Chen Y.(2015). Trimethylamine and trimethylamine N-oxide are supplementary energy sources for a marine heterotrophic bacterium: implications for marine carbon and nitrogen cycling. ISME J 9760–769. 10.1038/ismej.2014.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay R. J., McEntyre C. J., Henderson C., Lever M., George P. M.(2011). Trimethylaminuria: causes and diagnosis of a socially distressing condition. Clin Biochem Rev 3233–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-del Campo A., Bodea S., Hamer H. A., Marks J. A., Haiser H. J., Turnbaugh P. J., Balskus E. P.(2015). Characterization and detection of a widely distributed gene cluster that predicts anaerobic choline utilization by human gut bacteria. MBio 6e00042–15. 10.1128/mBio.00042-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccrindle S. L., Kappler U., McEwan A. G.(2005). Microbial dimethylsulfoxide and trimethylamine-N-oxide respiration. Adv Microb Physiol 50147–201. 10.1016/S0065-2911(05)50004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méjean V., Iobbi-Nivol C., Lepelletier M., Giordano G., Chippaux M., Pascal M. C.(1994). TMAO anaerobic respiration in Escherichia coli: involvement of the tor operon. Mol Microbiol 111169–1179. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrenko P., Lobb B., Kurtz D. A., Neufeld J. D., Doxey A. C.(2015). MetAnnotate: function-specific taxonomic profiling and comparison of metagenomes. BMC Biol 1392. 10.1186/s12915-015-0195-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravcheev D. A., Thiele I.(2014). Systematic genomic analysis reveals the complementary aerobic and anaerobic respiration capacities of the human gut microbiota. Front Microbiol 5674. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano K. A., Vivas E. I., Amador-Noguez D., Rey F. E.(2015). Intestinal microbiota composition modulates choline bioavailability from diet and accumulation of the proatherogenic metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. MBio 6e02481–14. 10.1128/mBio.02481-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleator R. D., Hill C.(2002). Bacterial osmoadaptation: the role of osmolytes in bacterial stress and virulence. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2649–71. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Steindler L., Thrash J. C., Halsey K. H., Smith D. P., Carter A. E., Landry Z. C., Giovannoni S. J.(2011). One carbon metabolism in SAR11 pelagic marine bacteria. PLoS One 6e23973. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson B.‐G., Akesson B., Nilsson A., Paulsson K.(1994). Urinary excretion of methylamines in men with varying intake of fish from the Baltic Sea. J Toxicol Environ Health 41411–420. 10.1080/15287399409531853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. H., Hazen S. L.(2014). The contributory role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest 1244204–4211. 10.1172/JCI72331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. H., Wang Z., Levison B. S., Koeth R. A., Britt E. B., Fu X., Wu Y., Hazen S. L.(2013). Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 3681575–1584. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Klipfell E., Bennett B. J., Koeth R., Levison B. S., Dugar B., Feldstein A. E., Britt E. B., Fu X., et al. (2011). Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 47257–63. 10.1038/nature09922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter S. E., Lopez C. A., Bäumler A. J.(2013). The dynamics of gut-associated microbial communities during inflammation. EMBO Rep 14319–327. 10.1038/embor.2013.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Gregory J. C., Org E., Buffa J. A., Gupta N., Wang Z., Li L., Fu X., Wu Y., et al. (2016). Gut microbial metabolite TMAO enhances platelet hyperreactivity and thrombosis risk. Cell 165111–124. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Jameson E., Crosatti M., Schafer H., Rajakumar K., Bugg T. D. H., Chen Y.(2014). Carnitine metabolism to trimethylamine by an unusual Rieske-type oxygenase from human microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1114268–4273. 10.1073/pnas.1316569111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Data Bibliography

- 1.Rampelli, S. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=2558 (2013)

- 2.Buelow, E. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=2851 (2012)

- 3.Ley, R. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=265 (2008)

- 4.De Tender, C. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=8939 (2009)

- 5.Hattori, M. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=4778 (2007)

- 6.Gordon, J. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=98 (2012)

- 7.Hattori, M. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=29 (2007)

- 8.Gordon, J. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=10 (2008)

- 9.Hayashi, T. & Hattori, M. iMicrobe http://data.imicrobe.us/project/view/33 (2007)

- 10.Stal, L. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=7332 (2013)

- 11.Parker, R. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=3910 (2013)

- 12.Wilbanks, E. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=3755 (2014)

- 13.Meyer, F. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=119 (2007)

- 14.Biddle, J. F., Fitz-Gibbon, S., Schuster, S. C., Brenchley, J. E. & House C. H. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=105 (2013)

- 15.Schunck, H., Lavik, G., Desai, D. K., Großkopf, T., Kalvelage, T., Löscher, C. R., Paulmier, A., Contreras, S., Siegel, H., Holtappels, M., Rosenstiel, P., Schilhabel, M. B., Graco, M., Schmitz, R. A., Kuypers, M. M. M. & LaRoche J. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=6556 (2013)

- 16.Thompson, C. E., Beys-da-Silva, W. O., Santi, L., Berger, M., Vainstein, M. H. & Vasconcelos, A. T. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=6544 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Andreote, F. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=134 (2011)

- 18.Delong, E. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=38 (2010)

- 19.Mou, X., Sun, S., Edwards, R. A., Hodson, R. E. & Moran, M. A. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=46 (2007)

- 20.Mou, X., Sun, S., Edwards, R. A., Hodson, R. E. & Moran, M. A. MG-RAST http://metagenomics.anl.gov/metagenomics.cgi?page=MetagenomeProject&project=19 (2007)

- 21.Yutin, N., Suzuki, M. T., Teeling, H., Weber, M., Venter, J. C., Rusch, D. B. & Béjà, O iMicrobe http://data.imicrobe.us/project/view/26 (2008) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Lin, Y. C., Campbell, T., Chung, C. C., Gong, G. C., Chiang, K. P. & Worden, A. Z. CAMERA North Pacific metagenomes from Monterey Bay to Open Ocean (CalCOFI Line 67) (2007)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.