Abstract

Background

Despite proven efficacy and increased availability of therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), mortality for patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) remains high with a limited understanding of those at highest risk of death.

Study Design and Methods

This study utilized the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (2007–2012) to derive a prognostic score for mortality in hospitalized TTP patients. Odds ratios of death with various putative risk factors adjusted for age, gender and race were calculated (adjOR). Weighted average of adjOR estimates were incorporated in a risk stratified score.

Results

Among 8203 hospitalizations with TTP as primary admission diagnosis who underwent TPE, 613 deaths were identified (all-cause mortality 7.5%, median time-to-death 9 days with interquartile range 4–14 days). In multivariable logistic regression, arterial thrombosis (adjOR 6.7, 95%CI=1.1–40.9), intra-cranial hemorrhage (adjOR 6.1, 95%CI=1.6–23.2), age >=60 years (adjOR 3.5, 95%CI=2.1–5.6), renal failure (adjOR 2.6, 95%CI=1.5–4.5), ischemic stroke (adjOR 2.4, 95%CI=1.2–5.0), platelet transfusions (adjOR 2.2, 95%CI=1.2–4.1) and myocardial infarction (adjOR 2.3, 95%CI=1.2–4.6) were significant independent predictors of mortality in TTP patients who underwent TPE. A prognostic weighted mortality prediction scoring system incorporating arterial thrombosis, intracranial hemorrhage, age, renal failure, ischemic stroke, platelet transfusion and myocardial infarction showed very good discrimination and was predictive of 78.6% deaths.

Conclusions

Early and targeted therapy for high risk individuals should be used to guide management of TTP patients for improved survival outcomes.

Keywords: TTP, death, mortality, predictors, in-hospital

Introduction

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a clinico-pathological entity presenting as a severe thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) characterized by red cell fragmentation, profound thrombocytopenia, renal failure and neurologic involvement of variable severity due to accompanying microvascular thrombosis with tissue ischemia and infarction1–4. While TTP symptoms are classically defined as this pentad, many clinicians suspect TTP in patients with thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and elevated LDH5–7. Idiopathic TTP is primarily due to autoantibodies directed against ADAMTS13, while congenital TTP is characterized as a hereditary deficiency of ADAMTS13. TTP is a rare disease and thus the epidemiology is not very well characterized 1. Since the use of therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) or plasma infusion in the 1980s, mortality has substantially decreased from an extremely high rate of 90% reported in the 1960’s8 to 10–20%9,10. However, an analysis of U.S. multiple cause-of-death mortality data with TTP from 1968–1991 reported an increase in the TTP mortality rate over time despite the reports of significant improvement in survival associated with clinical use of plasma infusion and TPE11.

While it is widely recognized and accepted that TTP still has a high risk for in-hospital morbidity and mortality4,12,13, recent estimates of all-cause mortality in hospitalized TTP patients are not available. Additionally, survivors of TTP hospitalizations have been proposed to be at higher risk for long-term poor clinical outcomes and eventual premature death13,14. The French TMA group proposed predictors of mortality in the subgroup of TTP patients with severe ADAMTS13 deficiency13. However, a comprehensive prognostic risk predictive score of all-cause mortality in hospitalized patients with TTP remains elusive. This study aims to use a nationally representative database from six years to develop a prognostic risk stratified score aimed at identifying hospitalized TTP patients at the highest probability of a fatal outcome. Early and targeted aggressive therapy based on these factors could guide the management of hospitalized patients with TTP and warrant further studies to determine if these strategies can improve survival outcomes.

Methods

Data Source

Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) for the years 2007–2012 were merged and used for this study. We have previously reported the methodology for NIS database and its use for analysis15. The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the U.S., developed as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). NIS uses a multi-staged clustering design to provide a stratified probability sample of 20% of all hospital discharges among U.S. community hospitals (approximately 1000–1100 hospitals per year). Community hospitals, per definition of the American Hospital Association, are all non-federal, short-term general and specialty hospitals including academic medical centers. Children’s hospitals are also represented in the survey16. HCUP has selected hospitals in NIS to be maximally representative and generate nationally representative estimates such as to include 40–47 states and represent 90–97% of the US population over the different years.

Data in NIS is de-identified and includes one primary or principal diagnosis and up to 24 total secondary diagnosis codes, one primary and up to 14 secondary procedure codes, admission and discharge status, demographic information and hospital characteristics. The principal diagnosis (the chief reason that was responsible for the admission) is coded in the first diagnosis field. All-listed diagnoses (Dx1–Dx25) include principal diagnosis plus additional conditions that either develop during the course of hospitalization or may co-exist at the time of admission. Data on laboratory values and pharmacological therapies administered during the course of an inpatient stay are not available in the NIS. The ‘unit of analysis’ is a hospital discharge and not a specific patient. Thus, the same patient could have had multiple hospitalizations in a specific year and will be captured each time as a separate hospitalization. However, our main outcome of mortality would be captured once only and there cannot be multiple hospitalizations with mortality. As HCUP-NIS is a de-identified, publicly available data set, informed consent was not obtained. HCUP guidelines in granting the authors access to NIS data set were followed, and all authors signed the data-use agreement.

Identification of discharges

TTP cases were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code 446.6. Only the hospital admissions with the “primary admitting diagnosis” of TTP were included in the analyses. We further restricted analyses only to the admissions with TPE listed as a concurrent procedure during the hospital stay with a goal to increase the specificity of the TTP diagnosis and treatment. We also excluded any cases with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (n=40) to exclude cases of transplant associated microangiopathy. There are no separate identified ICD-9 codes for HIV associated microangiopathy and quinine associated TMA.

Thrombotic events (arterial/venous) were identified using the available listing from AHRQ’s Patient Safety Indicators list (Appendix 1). Hospitalizations with reported prior ‘history of thrombosis’ identified by diagnosis codes V12.51, V12.52 or V12.55 were excluded. Using the ICD-9-CM coding, we identified cases of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), gastrointestinal bleed (GIB) and/or genitourinary bleed (GUB) as “bleeding” for the purpose of our analysis (Appendix 2).

Statistical Analyses

Data stratification and analysis was performed using SAS (Statistical Analysis Software Version 9.3.0, SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC). In accordance with HCUP NIS data use agreement, any tabulated data with ten or less than ten discharges were not reported. 17

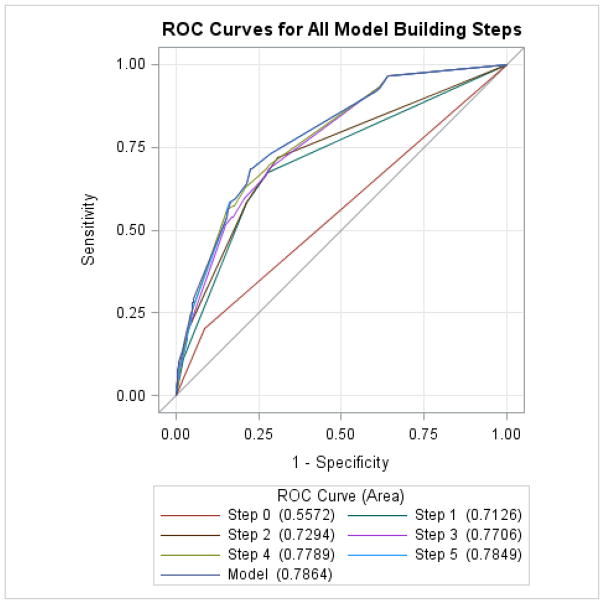

Quantitative variables were summarized by mean (standard deviation) and compared by the Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test; categorical data were summarized as count (%) and compared by the chi-square test. Univariate and stepwise multivariable logistic regression analyses with elimination were used for statistical analyses. Based on results of univariate analysis, the significant variables were added in a stepwise manner in a multivariable model. All variables selected for the multivariable model were tested for interaction with a significance threshold level of p<0.2. A Receiver Operator Characteristics (ROC) curve was constructed as each risk factor was added in multivariable analysis. All hypothesis testing was two tailed and p<0.05 was considered significant.

Using SAS PROC SURVEY and SUDAAN methodology, SAS 9.3.0 callable version, sampling weights were applied to represent all community hospital discharges in the U.S. in 2007–2012. As an average between these years, the sampling frame for the NIS is expected to represent 81% of community hospital discharges across various participating states and projected to cover 90–97% the U.S. population.

Multivariable logistic regression was repeated with and without clustering for hospital effects. Clustering the patients by hospitals is expected to produce more reliable 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) by taking into account the inter-facility correlation of patient outcomes as outcomes are more likely to be similar within rather than across hospitals18 and has reliably been used in more recent publications using the NIS19.

Sensitivity Analysis

We merged the NIS severity files with the core hospital files and adjusted for 1) total number of chronic conditions/co-morbidities at the time of the admission and 2) severity/acuity using All Payer Refined-Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs) severity and mortality indices. APR-DRG’s are a validated inpatient classification system widely used in United States as a case-mix measure and account for severity of illness, risk of mortality, prognosis, treatment difficulty, need for intervention and resource intensity 20.

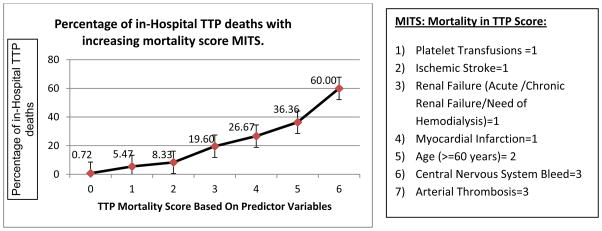

TTP Mortality Score Development

Using weighted averages of rounded coefficients from the multivariable analysis, we designed a Mortality In TTP Score (MITS) taking discrete values from 1 to 3 for each variable. Total scoring was calculated for each predictor variable being present or absent in a TTP admission and MITS score thus calculated. Area under the ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve was calculated to evaluate the discriminating power of the MITS score for predicting mortality.

Results

A total of 8,203 hospitalizations with TTP as the ‘primary admission diagnosis’ and also underwent TPE were identified nationwide over the 6 years (2007–2012) (Table 1). Overall, hospitalizations rates were fairly similar across the 6 years (1092, 1301, 1404, 1616, 1400, 1390 hospitalization for each year from 2007–2012 respectively). Of these, a total of 613 deaths were identified (all-cause in-hospital mortality rate 7.5% (613/8,203). The median time-to-death was 9 days with interquartile range of 4–14 days. The majority of deaths occurred in females (66.4%), whites (62.0%) and age 60 years or above (44.0%) (Table 1). Mean age for subjects who died was 60.1 years and significantly higher than the mean age of 45.6 years for subjects who survived (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Univariate associations of various putative predictor variables with in-hospital mortality in TTP patients who underwent TPE. (Using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2007–2012).

| All patients* | In-hospital Deaths* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of subjects | % | # of subjects | % | Odds Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value | |

| All TTP patients who underwent TPE | 8203* | 100.00 | 613* | 100.00 | ||||

| DEMOGRAPHICS | ||||||||

| Age Categories | ||||||||

| Children (<18 years old) | 109 | 1.3 | ** | ** | 1.47 | 0.19 | 11.42 | 0.63 |

| 18–44 years age (reference) | 3629 | 44.2 | 115 | 15.89 | 1 | |||

| 44–59 years old | 2616 | 31.9 | 160 | 39.25 | 2.05 | 1.19 | 3.53 | <0.01 |

| 60 years and above | 1849 | 22.5 | 333 | 44.0 | 6.78 | 4.15 | 11.08 | <0.0001 |

| GENDER | ||||||||

| Male | 2686 | 32.8 | 203 | 33.6 | 1 | |||

| Female | 5507 | 67.2 | 410 | 66.4 | 0.94 | 0.61 | 1.45 | 0.78 |

| RACE*** | ||||||||

| African-American (reference) | 2840 | 47.2 | 303 | 27.0 | 1 | |||

| Caucasian. | 3164 | 38.8 | 134 | 62.0 | 2.15 | 1.35 | 3.44 | <0.01 |

| Others**** | 948 | 14.0 | 56 | 11.0 | 1.22 | 0.59 | 2.51 | 0.58 |

| IN-HOSPITAL COMPLICATIONS | ||||||||

| CNS Bleed | 89 | 1.1 | 27 | 4.3 | 6.83 | 2.29 | 20.39 | <.001 |

| Non Central Nervous Bleeding. | 936 | 11.4 | 110 | 17.9 | 1.70 | 0.98 | 2.94 | 0.06 |

| Arterial Thrombosis | 35 | 0.4 | 15 | 2.5 | 13.47 | 2.68 | 67.61 | <0.001 |

| Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) | 463 | 5.6 | 103 | 16.7 | 3.61 | 1.97 | 6.61 | <.0001 |

| Ischemic Stroke | 460 | 5.6 | 96 | 15.6 | 3.67 | 2.00 | 6.74 | <.0001 |

| PROCEDURES | ||||||||

| Platelet Transfusion | 791 | 9.6 | 120 | 19.6 | 2.45 | 1.52 | 3.96 | <0.001 |

| RBC Transfusion | 3284 | 40.0 | 332 | 54.2 | 1.87 | 1.30 | 2.70 | <0.001 |

| COMORBIDITIES | ||||||||

| Renal Failure | 4432 | 54.0 | 494 | 80.6 | 3.88 | 2.46 | 6.13 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes | 1154 | 16.1 | 67 | 12.7 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 1.37 | 0.37 |

| Obesity | 903 | 12.6 | 54 | 10.2 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 1.49 | 0.46 |

| Hypertension | 3694 | 51.6 | 278 | 53.0 | 1.07 | 0.72 | 1.59 | 0.72 |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | 391 | 4.8 | 35.2 | 5.7 | 1.21 | 0.54 | 2.69 | 0.64 |

Subjects included in these analyses are defined as those with the ICD-9-CM discharge code of TTP who underwent TPE.

Data values <10 and not shown per HCUP guidelines.

Race has missing data on 15.4% (n=257) of the TTP subjects who underwent TPE

Other races include: Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islanders, Native Americans and other minority races.

The univariate (unadjusted) odds ratio estimates of various putative predictor variables for in-hospital mortality in TTP subjects who underwent TPE are also listed in Table 1. The following arterial ischemic/thrombotic complications were reported in TTP deaths: arterial thrombosis 2.5%, acute myocardial infarction 16.7% and ischemic stroke 15.6%. The following bleeding complications were reported in TTP deaths: CNS bleed 4.3%, gastrointestinal/genitourinary bleed 17.9%. We ran cross tabulations for subjects with ischemic stroke and CNS bleeding to see if they overlapped and thus could indicate that these were re-perfusion bleeds. However, there was overlap of diagnosis in only 1.6% of cases. A total of 19.6% and 54.2% of all TTP subjects who died received platelet and RBC transfusions respectively. Platelet transfusions, RBC transfusions, hemodialysis, renal failure (acute renal failure/chronic renal failure/hemodialysis) were significant predictors of TTP mortality. Other co-morbidities including female sex, obesity, hypertension, and systemic lupus erythematosus did not emerge as significant predictors of mortality.

In stepwise multivariable logistic regression analysis the following factors remained significant independent predictors of TTP mortality (Table 2): 1) arterial thrombosis (adjOR 6.73, 95%CI=1.11–40.91), 2) intra-cranial hemorrhage (adjOR 6.05, 95%CI=1.58–23.24), 3) age >=60 years (adjOR 3.47, 95%CI=2.14–5.63), 4) renal failure (adjOR 2.56, 95%CI=1.46–4.47), 5) ischemic stroke (adjOR 2.42, 95%CI=1.17–5.01), 6) platelet transfusions (adjOR=2.19, 95%CI=1.19–4.05) and 7) myocardial infarction (adjOR 2.32, 95%CI=1.16–4.63). The above model had an area under receiver operating characteristic curve of 78.6% (Figure 1). The model showed statistically significant calibration and fit per the Hosmer-Lemeshaw goodness-of-fit test.

Table 2.

Multivariable Analyses: Predictors of Hospital Mortality in Patients with a Primary Diagnosis of TTP (only subjects who underwent TPE are included in this analysis.)

| Predictor variables in the multivariable model | Odds Ratio Estimates | 95% Wald Confidence Limits | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet Transfusion | 2.19 | 1.19 | 4.05 | <0.05 |

| Intracranial Hemorrhage | 6.05 | 1.58 | 23.24 | <0.01 |

| Arterial Thrombosis | 6.73 | 1.11 | 40.91 | <0.05 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 2.32 | 1.16 | 4.63 | <0.05 |

| Ischemic Stroke | 2.42 | 1.17 | 5.01 | <0.05 |

| Age (>=60 years) | 3.47 | 2.14 | 5.63 | <.0001 |

| Renal Failure | 2.56 | 1.46 | 4.47 | <0.01 |

| Non Central Nervous System Bleeding** | 1.21 | 0.62 | 2.38 | 0.57 |

| Gender** | 1.10 | 0.67 | 1.79 | 0.71 |

| Race (Caucasians versus African Americans)** | 1.47 | 0.88 | 2.45 | 0.14 |

Area under receiver operating characteristic curve: 78.6%

Significant factors are in boldface type. Model is also adjusted for Gender, Non Central Nervous System Bleeding and Race (Caucasian versus African American)

Good model calibration and fit per the hosmer-lemeshaw goodness-of-fit test

Figure 1.

Receiving Operator Character (ROC) Curve with each factor being added to the stepwise logistic regression model. Final area under the ROC curve after all model building steps: 78.6%.

We used a weighted average of the beta coefficients estimates from the above multivariable predictor model and incorporated the 7 predictor variables to calculate the MITS score in TTP patients who underwent TPE. The followings scoring schema was used: platelet transfusions =1, CNS bleed=3, arterial thrombosis=3, age (60 years or above) =2, acute myocardial infarction=1, ischemic stroke=1 and renal failure (Acute Renal Failure/Chronic/Hemodialysis) =1.

There was significant upward trend in observed TTP mortality with each gradient of increase in TTP score by 2 points (p-value for trend <0.001) (Figure 2). Using the sensitivity and specificity for each possible mortality score for all patients, the AUC of the mortality score was 78.6% showing a very good discriminatory power between predicting death versus survival.

Figure 2.

Mortality in TTP score (MITS): Total TTP mortality score and corresponding observed percentage of in-hospital TTP deaths in patients who underwent TPE (Using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2007–2012). Total mortality score was calculated based on a weighted average of the odds ratio estimates from the multivariable model for TTP patients who underwent TPE and corresponding reported percentage of deaths. There were too few to report numbers and percentages at TTP score of 7 and results are not shown per HCUP data use guidelines.

In sensitivity analyses of a) excluding individuals co-diagnosed with hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) (Supplemental Table 1a) and b) adjusting for the total number of chronic conditions/chronic co-morbidities documented for the patient during the hospitalization in the model, the model remains robust and all the factors remained significant (Supplemental Table 1b). We also adjusted for the APR-DRG severity index, all factors remained significant in the model except renal failure (Supplemental Table 1c). There was collinearity with renal failure as the majority of patients were in the highest grade of severity of illness itself.

Discussion

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is a life-threatening clinic-pathological disorder involving multiple organ systems, which remains a management challenge to physicians. If not treated promptly, TTP typically follows a progressive deteriorating course with irreversible renal failure, progressive neurologic deterioration, cardiac ischemia, and death1,21. Overt signs of end-organ damage such as brain or cardiac infarction may present late. Here we present a set of independent clinical predictors of poor outcome in hospitalized TTP patients despite undergoing TPE and derive a weighted prognostic scoring schema based on these factors to identify patients at highest risk for an adverse outcome.

While early diagnosis of the condition combined with rapid TPE/plasma infusion has led to a dramatic improvement in overall prognosis from earlier reported 90% mortality8, TTP still has poor overall survival1,9. Not only does the disease entail high risk of imminent death, long term follow up data from the Oklahoma TTP registry provides evidence that TTP survivors may have greater risk for poor health and premature death as compared with US general population14.

TPE is the currently accepted mainstay in TTP management and should be instituted even if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis as the potential risks of rapid deterioration with delayed treatment much exceed the procedural risks associated with TPE2,22,23. In the absence of TPE, early mortality of clinical presentation remains an issue22,24. However, it is also critical to identify which patients are at highest risk of adverse outcomes despite initiation of TPE therapy2,12,22. For this reason as well as to increase the specificity of diagnosis of TTP, we restricted our further analyses only to TTP admissions with TPE as a documented procedure.

Until now, a comprehensive risk score predicting all-cause mortality in hospitalized patients with TTP has not been proposed. The ability to identify accurate prognostic factors in TTP has been limited due to small sample sizes/case series being available. Registry level data is being increasingly used successfully in studying outcomes in these rare diseases25. Using data from the Canadian Apheresis Group registry, Wyllie et al proposed a new index predicting 6 month mortality based on clinical variables at presentation including fever, low platelet count, low hemoglobin and advanced age26. Recognizing the need for a predictive model for mortality in TTP, a French group recently proposed that individuals who were older, had arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, cerebral manifestations, increased creatinine levels and increased lactate dehydrogenase levels were more likely to die among a cohort of about 30 deaths in TTP patients with confirmed severe ADAMTS13 deficiency13. The primary predictors of mortality identified from our model included increasing age especially ≥60 years, platelet transfusions, central nervous system bleeding, renal failure, arterial thrombosis, acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Increasing age was an important predictor of survival with older patients showing worse outcomes. In particular, age ≥60 years was most susceptible to increased mortality even after adjusting for other comorbidities, as also shown in other studies13,27. Platelet transfusions were also an independent risk factor for mortality. While there is biological plausibility to the relationship, there has essentially been case report or small case series level evidence supporting the relationship 28,29. Our group has recently published data demonstrating an association of platelet transfusions with arterial thrombosis and higher odds of death in TTP patients 15. While platelet transfusions could themselves be associated with thrombotic events 30,31, arterial thrombosis as well as ischemic stroke continue to remain significant independent predictors of mortality in TTP patients. There is recent evidence suggesting that cryptogenic stroke with vascular distributions suggesting a distal micro-embolic pattern and other neurovascular complications of TTP may actually develop before the onset of profound hematologic abnormalities32,33. Central nervous system (CNS) bleeding is not commonly reported in TTP subjects. However, we found almost 5 times higher incidence of CNS bleeding in TTP subjects who died. We also identified myocardial infarction as an independent predictor of death in TTP patients. It has previously been reported that these patients frequently die from a specific arrhythmia (pulseless electrical activity) that is likely due to ischemia34. In addition, post mortem studies of patients with TTP report myocardial infarction as the most common autopsy finding suggesting that the mechanism of death is commonly cardiac in origin 35,36. It is notable that ischemic stroke, AMI as well as arterial thrombosis were seen in our data more in the middle age (44–59 years age) and elderly (60 years or above in age). Renal failure (acute/chronic and with dialysis dependence) was also associated with worse outcome in TTP patients and higher adjusted odds of death. Varying degrees of renal dysfunction ranging from elevated creatinine to renal failure warranting dialysis have previously been reported as being associated with adverse outcomes in TTP patients but not death13,27. In our data, renal failure was seen in the sickest TTP patients with >3/4th of the subjects being in the highest grade of severity of illness by the APR-DRG severity scoring and was identified as a significant independent predictor of death. The MITS score derived from above listed factors showed a significant upward trend in observed TTP mortality with each gradient of increase in total score and showed a very good discriminatory power between predicting death versus survival. However, renal failure is often a late finding with TTP and a recent consensus conference noted that renal failure at time of initial diagnosis should be taken as a cautionary note regarding the diagnosis of TTP 6.

There are a few limitations of this study. TTP can be idiopathic or secondary, and there are several causes of secondary TTP. As the case identification is based on ICD-9-CM discharge coding for thrombotic microangiopathy, and there are no individual codes yet for primary/secondary TTP, so we cannot distinguish these cases. The NIS database unfortunately does not include ADAMTS13 data or particular treatments such as rituximab. However, to increase specificity of the TTP diagnoses, we restricted the analysis to individuals who had a primary diagnosis of TTP and also received TPE. The median time to death was 9 days among individuals diagnosed with TTP and initiated TPE. However, the increased specificity of requiring TPE for the TTP diagnosis in this cohort may artificially be inflating the time to death by excluding individuals who died prior to TPE initiation. We also excluded the hematopoietic stem cell transplant cases and identified that Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS) was simultaneously coded in only 10% cases; the mortality score holds robust after excluding the HUS cases in a sensitivity analysis. In addition, the ICD-9-CM coding permits large numbers of individuals to be evaluated. Our study provides the largest cohort of mortality in TTP patients to date with estimated >1000 TTP-related deaths identified over 6 years across approximately 1100 hospitals nationwide to propose a set of clinical predictors of mortality.

This study provides prognostic factors for patients with TTP at highest risk of death. Early and empiric TPE remains the mainstay of therapy. However, despite TPE, if any of the adverse criteria included in the MITS score develop, it should alert the treating physician to have a higher index of suspicion for adverse outcomes including mortality. Variables seen at presentation, besides older age, alone may not be sufficient to predict in-hospital mortality as various complications that develop during the course of hospitalization may significantly alter the clinical course and prognosis. Platelet transfusions should be avoided in patients with TTP. In addition, patients with TTP would likely benefit from empiric and proactive monitoring for intracranial hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, arterial thrombosis, myocardial infarction and renal failure. We believe the mortality score should be applicable at each point of the treatment course ranging from diagnosis through the entire range of the treatment course including remission, relapse or refractory disease as complications can develop at any point of the clinical course. We have also shown a progressively higher probability of death as adverse factors accumulate and the total MITS score increases. Thus development of additional adverse events in a patient should alert the clinician for the possibility of a deteriorating course or a poorer outcome. Patients identified at high risk of mortality from the MITS score despite performing TPE may signify aggressive or refractory disease and may be candidates for intensive care monitoring and/or early institution additive therapies, such as standard treatments of glucocorticoids and rituximab or newer therapies of caplacizumab, N-acetylcysteine, eculizumab, and bortezomib.37

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: A.A.R.T. was supported by the NIH 1K23AI093152-01A1

Footnotes

Conflicts: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.George JN. Clinical practice. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1927–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp053024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: 2010. Blood. 2010;116:4060–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-271445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadler JE, Moake JL, Miyata T, George JN. Recent advances in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2004:407–23. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2004.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamski J. Thrombotic microangiopathy and indications for therapeutic plasma exchange. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014;2014:444–9. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raval JS, Mazepa MA, Brecher ME, Park YA. How we approach an acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura patient. Transfusion. 2014;54:2375–82. doi: 10.1111/trf.12794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarode R, Bandarenko N, Brecher ME, Kiss JE, Marques MB, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Winters JL. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: 2012 American Society for Apheresis (ASFA) consensus conference on classification, diagnosis, management, and future research. J Clin Apher. 2014;29:148–67. doi: 10.1002/jca.21302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandarenko N, Brecher ME. United States Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura Apheresis Study Group (US TTP ASG): multicenter survey and retrospective analysis of current efficacy of therapeutic plasma exchange. J Clin Apher. 1998;13:133–41. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1101(1998)13:3<133::aid-jca7>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox EC. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: report of three additional cases and a short review of the literature. J S C Med Assoc. 1966;62:465–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, Blanchette VS, Kelton JG, Nair RC, Spasoff RA. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Canadian Apheresis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:393–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108083250604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell WR, Braine HG, Ness PM, Kickler TS. Improved survival in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clinical experience in 108 patients. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:398–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108083250605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torok TJ, Holman RC, Chorba TL. Increasing mortality from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in the United States--analysis of national mortality data, 1968–1991. Am J Hematol. 1995;50:84–90. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kremer Hovinga JA, Vesely SK, Terrell DR, Lammle B, George JN. Survival and relapse in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2010;115:1500–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-243790. quiz 662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benhamou Y, Assie C, Boelle PY, Buffet M, Grillberger R, Malot S, Wynckel A, Presne C, Choukroun G, Poullin P, Provot F, Gruson D, Hamidou M, Bordessoule D, Pourrat J, Mira JP, Le Guern V, Pouteil-Noble C, Daubin C, Vanhille P, Rondeau E, Palcoux JB, Mousson C, Vigneau C, Bonmarchand G, Guidet B, Galicier L, Azoulay E, Rottensteiner H, Veyradier A, Coppo P Thrombotic Microangiopathies Reference C. Development and validation of a predictive model for death in acquired severe ADAMTS13 deficiency-associated idiopathic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: the French TMA Reference Center experience. Haematologica. 2012;97:1181–6. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.049676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deford CC, Reese JA, Schwartz LH, Perdue JJ, Kremer Hovinga JA, Lammle B, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, George JN. Multiple major morbidities and increased mortality during long-term follow-up after recovery from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2013;122:2023–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496752. quiz 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goel R, Ness PM, Takemoto CM, Krishnamurti L, King KE, Tobian AA. Platelet transfusions in platelet consumptive disorders are associated with arterial thrombosis and in-hospital mortality. Blood. 2015;125:1470–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-605493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Association AH. Fast Facts on US Hospitals. 2014 http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/fast-facts.shtml [monograph on the internet]

- 17.agreement Hdu. HCUP data use agreement. 2014 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/team/NationwideDUA.jsp.

- 18.Localio AR, Berlin JA, Ten Have TR, Kimmel SE. Adjustments for center in multicenter studies: an overview. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:112–23. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hicks CW, Hashmi ZG, Velopulos C, Efron DT, Schneider EB, Haut ER, Cornwell EE, 3rd, Haider AH. Association Between Race and Age in Survival After Trauma. JAMA Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Software MAD. 3M™ APR DRG Software. 2014 http://solutions.3m.com/wps/portal/3M/en_US/Health-Information-Systems/HIS/Products-and-Services/Products-List-A-Z/APR-DRG-Software/ [monograph on the internet]

- 21.Kiss JE. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: recognition and management. Int J Hematol. 2010;91:36–45. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0478-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scully M, Hunt BJ, Benjamin S, Liesner R, Rose P, Peyvandi F, Cheung B, Machin SJ British Committee for Standards in H. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and other thrombotic microangiopathies. Br J Haematol. 2012;158:323–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Baeyer H. Plasmapheresis in thrombotic microangiopathy-associated syndromes: review of outcome data derived from clinical trials and open studies. Ther Apher. 2002;6:320–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2002.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brailey LL, Brecher ME, Bandarenko N. Apheresis and the thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura syndrome: current advances in diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management. Ther Apher. 1999;3:20–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.1999.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George JN, Vesely SK, Terrell DR, Deford CC, Reese JA, Al-Nouri ZL, Stewart LM, Lu KH, Muthurajah DS The Oklahoma Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura-haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome Registry. A model for clinical research, education and patient care. Hamostaseologie. 2013;33:105–12. doi: 10.5482/HAMO-12-10-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyllie BF, Garg AX, Macnab J, Rock GA, Clark WF Members of the Canadian Apheresis G. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/haemolytic uraemic syndrome: a new index predicting response to plasma exchange. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:204–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balasubramaniyam N, Kolte D, Palaniswamy C, Yalamanchili K, Aronow WS, McClung JA, Khera S, Sule S, Peterson SJ, Frishman WH. Predictors of in-hospital mortality and acute myocardial infarction in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med. 2013;126:1016e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harkness DR, Byrnes JJ, Lian EC, Williams WD, Hensley GT. Hazard of platelet transfusion in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. JAMA. 1981;246:1931–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ridolfi RL, Bell WR. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Report of 25 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1981;60:413–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wongwiangjunt S, Poungvarin N. Extensive bilateral ischemic stroke after platelet transfusion in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP): a case report. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95(Suppl 2):S256–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tripathi SP, Deshpande AS, Khadse S, Kulkarni RK. Case of TTP with cerebral infarct secondary to platelet transfusion. Indian J Pediatr. 2011;78:109–11. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0224-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rojas JC, Banerjee C, Siddiqui F, Nourbakhsh B, Powell CM. Pearls and oy-sters: acute ischemic stroke caused by atypical thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Neurology. 2013;80:e235–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Downes KA, Yomtovian R, Tsai HM, Silver B, Rutherford C, Sarode R. Relapsed thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura presenting as an acute cerebrovascular accident. J Clin Apher. 2004;19:86–9. doi: 10.1002/jca.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brecher ME. How I approach a thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura patient. Transfusion. 2006;46:687–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nichols L, Berg A, Rollins-Raval MA, Raval JS. Cardiac injury is a common postmortem finding in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura patients: is empiric cardiac monitoring and protection needed? Ther Apher Dial. 2015;19:87–92. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosler GA, Cusumano AM, Hutchins GM. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic uremic syndrome are distinct pathologic entities. A review of 56 autopsy cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:834–9. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-834-TTPAHU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veyradier A. Von Willebrand Factor--A New Target for TTP Treatment? N Engl J Med. 2016;374:583–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1515876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.