Abstract

Objective: To obtain preliminary data on the effects of an auricular acupuncture protocol, Battlefield Acupuncture (BFA), on self-reported pain intensity in persons with chronic Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) and neuropathic pain.

Design: Pilot randomized delayed entry single center crossover clinical trial at an outpatient rehabilitation and integrative medicine hospital center.

Methods: Chronic (> one year post injury) ASIA impairment scale A through D individuals with SCI with injury level from C3 through T12 and below level neuropathic pain with at least five on the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) were recruited. Twenty-four subjects were randomized to either an eight-week once weekly ten-needle BFA protocol (n = 13) or to a waiting list followed by the BFA protocol (n = 11).

Outcome measures: The primary outcome measure was change in the pain severity NRS. Secondary outcome was the Global Impression of Change.

Results: Demographically there were no significant differences between groups. Mean pain scores at baseline were higher in acupuncture than control subjects (7.75 ± 1.54 vs. 6.25 ± 1.04, P = 0.027). Although both groups reported significant reduction in pain during the trial period, the BFA group reported more pain reduction than the delayed entry group (average change in NRS at eight weeks –2.92 ± 2.11 vs. −1.13 ± 2.14, P = 0.065). There was a significant difference in groups when a group-by-time interaction in a mixed-effect repeated measures model (P = 0.014).

Conclusion: This pilot study has provided proof of concept that BFA has clinically meaningful effect on the modulation of SCI neuropathic pain.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Auricular acupuncture, Battlefield acupuncture, Spinal cord injury, Neuropathic pain, Rehabilitation

Introduction

There is a heavy burden of suffering arising from neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury (SCI). Prevalence rates are reported to range widely from 26% to 96%,1 with the average being around 70%.2 With the prevalence of SCI in the United States estimated to be around 270,000,3 the number of individuals experiencing SCI-related pain is around 189,000. Finding effective treatments for neuropathic pain is a major concern expressed by persons with SCI.4,5 Current management of spinal cord damage-related pain still remains largely empirical, using data from small studies with no consensus on optimal management. Moreover, data from postal community surveys of adult persons with SCI and pain indicate a lack of pain relief from the use of several traditional and non-traditional treatments by a large majority of users.6–9 More than one third of persons with SCI pain have ongoing pain that is refractory to conventional treatments.10

Acupuncture has been used for treatment of persons with SCI, not just for pain but also for other SCI complications. In a recent review, sixteen randomized controlled trials in SCI were identified, with only two for pain control.11 One of these studies was considered to be of high quality based on the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale.12 In that study, seventeen manual wheelchair-using subjects with chronic musculoskeletal shoulder pain were randomly assigned to either shoulder acupuncture or invasive sham acupuncture consisting of light needling of non-acupuncture points. Shoulder pain intensity as measured on a 0–10 numeric rating scale (NRS) decreased significantly (P = 0.005) over the 10 treatments in both the acupuncture (66%) and sham (43%) groups. There was no statistical difference between the treatment and the sham groups, but the treatment group effect size was larger. The authors could not definitively conclude, however, that true acupuncture was better than what may have been a very strong placebo in the sham group.13 An earlier non-randomized study of SCI individuals who experienced at least six months of moderate to severe pain of various types found that about 50% of the enrollees reported substantial pain relief after treatment consisting of 15 acupuncture sessions over 7½ weeks. Some subjects, however (26%), experienced an increase in pain.14 Study of neuropathic pain related to SCI specifically using acupuncture has been limited.

A retrospective chart review of thirty-six patients with SCI and neuropathic pain by Rapson et al. suggests a beneficial effect of Electroacupuncture (EA) in 67% of the patients measured by the visual analog scale with this intervention.15 This protocol, developed at the Lyndhurst Centre in Canada, used low frequency EA (1–4 Hz) delivered for thirty minutes, on points along the Governing Vessel (GV) meridian. Three of these points were located along the midline of the scalp (GV 18, 20, and 21), and one in between the eyebrows (GV 24.5). Based on stereotactic mapping, the investigators postulated that this technique provides stimulation to the medial midbrain tegmentum, a region that has been shown to be sensitive to electrical stimulation in patients with neuropathic pain.

Battlefield Acupuncture (BFA) was first developed by Niemtzow as an attempt to design an auriculotherapy protocol for rapid relief of pain.16 Five acupoint zones are stimulated sequentially in both ear (cingulate gyrus, thalamus, omega-2, point zero and shen men). Both ears are used, and the patient's response determines the need for further needle insertion. Semi-permanent needles are used that can stay in place for three to seven days and are pushed out spontaneously with normal epidermal turnover. Selection of these points is based on data from fMRI studies that demonstrate the role of the cingulate gyrus and thalamus in central pain modulation,17–20 as well as on traditional teachings claiming that master points (point zero, shen men and omega-2) have an effect on relaxation, and on balancing the autonomic and neuro-endocrine systems. Benefits of stimulating two of these points (cingulate gyrus and thalamus) have been reported in a small, randomized trial on acute pain syndromes.21 Additionally, stimulation of certain ear acupuncture points has been shown to correlate with fMRI activation of cortical and limbic regions that are part of the pain matrix.22 The benefit of using the full BFA protocol, sequential stimulation of five acupoint zones in both acute and chronic pain conditions, have been reported in a case series.16 This protocol is simple to use, requires no undressing or positioning of the patient, and does not require the patient to remain in one position for an extended period of time during treatment. This translates to greater ease of use for both the person with SCI and the clinician.

We conducted this study to obtain preliminary data on the effects of this auricular acupuncture protocol, BFA, on the self-reported pain intensity of persons with chronic SCI and neuropathic pain to inform the design of future clinical trials.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a randomized delayed entry single center crossover pilot clinical trial. The University of Maryland Baltimore Institutional Review Board and the University of Maryland Rehabilitation and Orthopaedic Institute (UMROI, formerly Kernan Hospital) Medical Executive Committee approved this protocol.

Individuals were recruited as a convenience sample from the outpatient spinal cord injury clinics at UMROI and the VA Maryland Healthcare System, Baltimore Division that provide both rehabilitative and medical services to persons with acute and chronic SCI. IRB-approved flyers, posters, mailers, and an SCI patient database were used for recruitment. The study investigators conducted a medical record review to obtain the principal neurologic diagnosis, neuropathic pain diagnosis, other co-existing medical diagnoses, date and mechanism of injury, and other patient demographic data at the time of enrollment.

The study inclusion criteria included persons aged 18–65, with a complete or incomplete SCI of at least 12 months duration. All had a diagnosis of SCI neuropathic pain, defined as diffuse pain below the level of injury in areas without normal sensation and not affected by position, for at least six months. The pain intensity based on the NRS had to be of five or higher, experienced for most of the day, reported on two separate occasions, in spite of appropriate pharmacologic therapy. They must not have not received any acupuncture treatment in the past and be able to complete data collection instruments or have sufficient assistance to do so. The exclusion criteria included presence of skin breakdown or infection in the external ears, and active participation in other research studies using investigational anti-spasticity drugs, anabolic steroids, psychotropic medications, antidepressants, or analgesics.

All participants reviewed and signed a written IRB-approved consent form. The verification of informed consent included an item specific for participants who were unable to sign due to a motor deficit. All applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human subjects were followed. Compensation was given for each of the study participants to partially cover the expense of their travel, and for completing study instruments (i.e. pain scores, medication logs).

The participants underwent a complete history and physical examination, including a neurological examination following based on the International Standards for the Neurological and Functional Classification of SCI (ISNCSCI).23 The Bryce/Ragnarsson SCI Pain Taxonomy (BR-SCI-PT) was used to further classify neuropathic pain as above level, at-level, and below-level pain.24 Participants in the acupuncture group received weekly sessions for eight (8) weeks. Four weeks after termination of acupuncture (week 12), a follow-up visit was done to determine presence of any sustained effects on pain and medication usage in the absence of acupuncture. The participants in the treatment group were followed for an additional four weeks after cessation of the BFA as a washout period. After an eight-week observation period, the delayed entry control group crossed over to an eight week BFA intervention.

Description of the intervention

An adapted BFA protocol was used for this study. Gold sterile Auguille Semipermanent (ASP) needles were placed on both ears at all the five acupoint zones described previously (anterior cingulate, thalamus, omega-2, Shen Men, point zero). The needles employed were housed in a specifically designed plastic injector or plunger that was used for the needle placement. These were 2 mm in length and inserted approximately 1 mm. These were expected to fall off with the normal epidermal skin turnover within three to seven days. Participants were given written instructions on needle care. All subjects received a new set of needles weekly for 8 weeks. Two study acupuncturists performed all acupuncture procedures. The project consultant and developer of the BFA protocol (Niemtzow) reviewed and verified point location and needle placement with the study acupuncturists at project commencement.

Outcome measures and data collection

The primary outcome measure is the change of the average pain intensity score (NRS)25,26 at week 8 from baseline. Participants were instructed to use this scale to rate their average pain intensity for the past seven days, and also the pain intensity they experience at the time of the acupuncture visit. Other outcome measures used included the 7-Point Guy-Farrar Patient Global Impression of Change,27 and symptom questionnaires. Data on the period of time, measured in days, that the ASP needles remained in the ears was also noted at each acupuncture research visit. Data for NRS scores were collected at baseline/pretreatment, mid-treatment (4 weeks), post-treatment (8 weeks), and at follow-up (12 weeks). Pain medication logs were collected at baseline, each of their weekly treatment sessions, (weeks 1–8) and at 12 weeks. Symptom questionnaires were collected weekly form week 1–8. Data from the Patient Global Impression of Change scale were collected on weeks 8 and 12.

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographic data was compared between treatment and delayed entry control groups using Student's t tests. The primary outcome measure, namely the change in NRS at eight weeks compared to baseline was compared between groups also using Student's t testing. Further analysis was performed using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the primary outcome with time and group as predictors. This mixed effect model (i.e. generalized estimate equation) was used to assess reduction in pain in consideration of repeated measures and dropout by taking all available data points (intent-to-treat analysis). The perceived global impression of change scores were assessed with a t-test comparison.

Results

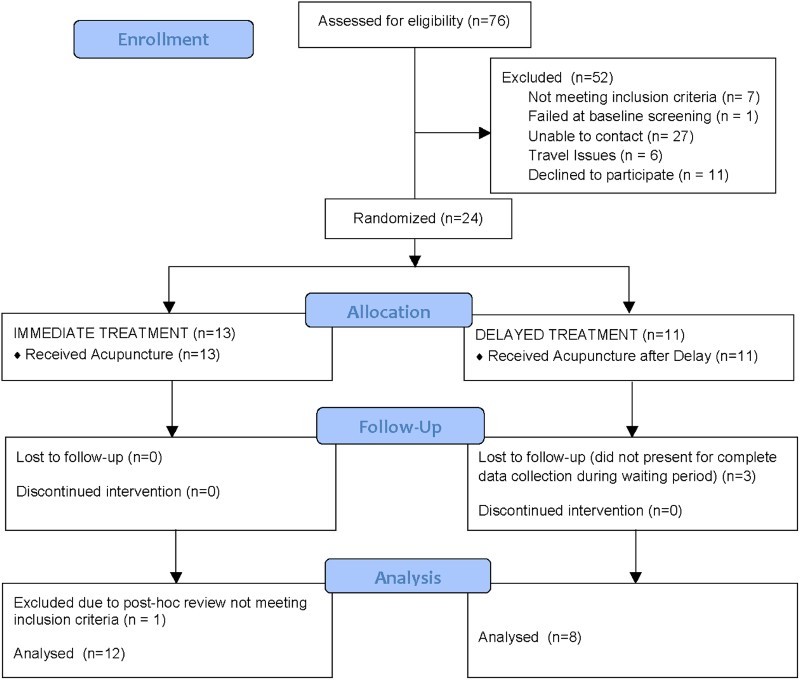

Figure 1 provides a CONSORT diagram of the enrollment process. There were 24 individuals that were randomized and received treatment in the study. Of those individuals, 18 were men and 6 were women. For the purposes of analysis, one of the individuals (a woman) was excluded from the immediate treatment group because post hoc review of her screening information identified that she did not meet the precise inclusion criteria of neuropathic pain below the level of the spinal cord injury. Three subjects in the delayed treatment group were also excluded from the principal analysis because primary outcome data (i.e. pain score at eight weeks) was not available. These individuals could be included in some of the other analyses.

Figure 1.

CONSORT (CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) flow chart of enrollment for Acupuncture Study.

Demographically, there were no significant differences between the immediate treatment and the delayed treatment groups (Table 1). Neurologically, the treatment group (n = 12) consisted of 25% cervical level injuries and 33% complete injuries. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the presence of other types of pain other than neuropathic pain below the level of the injury (#14), and only a small number of subjects (25% at the most for each classification) reported additional pain types.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics between immediate treatment and delayed treatment groups

| Immediate Treatment N = 12 | Delayed Treatment N = 8 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.1 | 46.1 | 0.470 |

| % Male | 83.3% | 75.0% | 0.535 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.354 | ||

| Caucasian | 8.3% | 37.5% | |

| African American | 75.0% | 50.0% | |

| Hispanic | 8.3% | 12.5% | |

| Asian | 8.3% | 0.0 | |

| Education | 0.083 | ||

| High School or Less | 8.3% | 50.0% | |

| College | 83.3% | 37.5% | |

| Graduate school | 8.3% | 12.5% | |

| Post injury time (years) | 7.6 | 13.0 | 0.349 |

| Level of injury: % Paraplegia | 75% | 25% | 0.262 |

| ASIA Impairment Scale (%) | 0.597 | ||

| A | 33.3% | 12.5% | |

| B | 8.3% | 12.5% | |

| C | 33.3% | 25.0% | |

| D | 25.0% | 50.0% | |

| Bryce Ragnarsson Pain Taxonomy at baseline (%) | |||

| 1 (Above/noc/mechanical) | 8.3% | 12.5% | 0.761 |

| 4 (At/neuro/compressive) | 8.3% | 0.0 | 0.402 |

| 5 (At/neuro/other) | 8.3% | 0.0 | 0.402 |

| 6 (Below/noc/mechanical) | 8.3% | 12.5% | 0.761 |

| 8 (Below/neuro/radic) | 25.0% | 0.0 | 0.125 |

| 9 (Below/neuro/compressive) | 0.0 | 25.0% | 0.068 |

| 12 (Below/noc/mechanical) | 25.0% | 12.5% | 0.494 |

| 14 (Below/neuro/central) | 100% | 100% |

ASIA = American Spinal Injury Association; Above = Above level of injury; At = At level of injury; Below = Below level of injury; noc = nociceptive; neuro = neuropathic

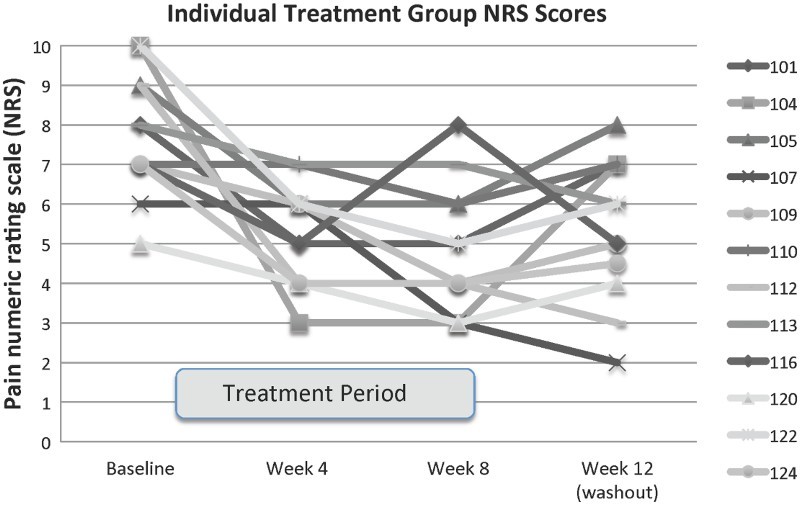

The primary outcome measure was the change in the pain severity NRS. Repeated measures (four and eight week data) analysis of the NRS pain scores was performed with a mixed-effect model. Mean pain scores at baseline were higher in acupuncture than control subjects (7.75 ± 1.54 vs 6.25 ± 1.04, P = 0.027). Table 2 represents the NRS values for the acupuncture and the delayed entry control group. Although both groups reported significant reduction in pain during the trial period, the BFA group reported significantly more pain reduction than the delayed entry group (average change in NRS at eight weeks –2.92 ± 2.11 vs. –1.13 ± 2.14, P = 0.065), which was also reflected in the significant group-by-time interaction in the mixed-effect model (P = 0.014). This statistic is a repeated measures analysis and includes the available four week data. The effect size of the treatment group from baseline to eight weeks was 1.84 (using Cohen's d), and the effect size of the delayed entry control group was 0.76. Therefore the difference in effect sizes is calculated as 1.08. It was also observed that 1) there was an overall worsening of average pain scores four weeks after discontinuation of the eight weeks of therapy, although week 12 pain scores only reverted on average 19% back to baseline and 2) there was an 0.75 point reduction in pain on average from week 8 to week 16 after the control group crossed over to treatment at the end of their eight week waiting list period. Figure 2 details individual pain scores for the treatment group during the eight weeks of treatment and after a four-week washout period.

Table 2.

Pain numeric rating scales for both groups over time (± standard deviation). N values at different at certain time intervals in the control group because of missing data. BFA = Battlefield Acupuncture

| Baseline | Week 4 | Week 8 | Crossover Week 12 | Crossover Week 16 | Washout 4 weeks after BFA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 7.75 ± 1.54 | 5.25 ± 1.29 | 4.83 ± 1.64 | — | — | 5.38 ± 1.80 |

| n | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | ||

| Delayed Entry | 6.25 ± 1.04 | 7.0 ± 0.0 | 5.13 ± 1.81 | 5.09 ± 1.51 | 4.38 ± 1.30 | 5.50 ± 1.69 |

| n | 8 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 |

| Change from baseline to 8 weeks | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | –2.92 ± 2.11 | |||||

| Delayed Entry | –1.13 ± 2.14 | |||||

Figure 2.

Pain numeric rating scores for the subjects randomized to immediate treatment both during the eight-week intervention and after 4 weeks without BFA therapy. Each line represents a different subject in the group randomized to treatment first. The treatment period is indicated by the grey rectangle along the x-axis.

The Guy-Farrar Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) was also used in this trial. The data collected at the end of week eight showed a mean improvement score compared to baseline for the BFA group of 4.62 ± 1.04 (n = 12) whereas the control group PGIC was 2.25 ± 1.98 (n = 8). The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.011) even with this small sample size using a two-tailed Students t-test.

Discussion

This pilot controlled clinical trial provides preliminary evidence that BFA has a beneficial effect on below level neuropathic pain in individuals with spinal cord injury. Our results in a fairly small number of subjects documented improvement in pain numeric rating scores in those who underwent the treatment greater than those that had delayed intervention. Using a repeated measures analysis that allowed for pooling of both the four and eight week data, the difference between the two groups reached statistical significance. Follow up data four weeks after completion of the BFA intervention, although not statistically significant, suggested a trend to return towards baseline pain. Patient global impression of change measures at eight weeks demonstrated a significant difference between the immediate and the delayed treatment groups.

This study, although controlled, was not a blinded investigation. Indeed, blinded trials involving acupuncture are difficult to accomplish. Clinical trials involving acupuncture for chronic pain are challenging in that the choice of control measures for the comparison group can influence the effect size of the treatment.28,29 Several choices for control measures exist. There can be an active control that consists of a sham procedure. Sham procedures can include non-needle sham, penetrating sham needles and non-penetrating sham needles. There can also be a non-sham control that includes non-specified routine care, protocol-guided care, or no care, which may be followed later by the treatment being trialed (e.g. delayed entry crossover or waitlist control as was done in this study). In the individual patient data meta-analysis mentioned above of subjects in high quality trials for four sources of chronic pain (back and neck, osteoarthritis, chronic headache and shoulder pain), acupuncture reduced pain scores by 0.15 to 0.23 standard deviations in comparison to sham acupuncture. In contrast, in meta-analysis of studies that utilized non-sham controls, the effect sizes ranged from 0.42 to 0.57.28 Therefore, a non-sham controlled trial often results in a larger effect size, suggesting a greater placebo effect. In this study our effect size was 1.84 points on the NRS compared to that of 0.76 for the delayed entry group, or a difference of 1.08. Therefore, compared to other non-sham controls, our study resulted in quite a robust effect size. Future studies might need to further address the placebo control issues through the use of some sort of simulated acupuncture intervention such as the placement of beads over the relevant auricular sites. This has also been termed “sham” acupuncture by some authors in that it may provide a mock treatment that is believed by the subject to be an acupuncture treatment, but is missing the theorized active needling component.30

A minimal clinically meaningful difference in pain control due to any intervention has been generally established to be about two points on the NRS.31 Specifically in the spinal cord injury population, a report based on reanalysis of prior data indicated that an average decrease of 1.80 points and percentage decrease of 36% corresponded to patient report of a meaningful change in pain.32 Our study, albeit small, certainly achieved this open label threshold.

The study was limited by a number of lost data points, especially in the control or delayed treatment arm of the study. This methodological problem may have been related to the lack of incentive on the part of the patients randomized to delayed entry to participate in all of the data collection points. Design of future studies will need to address this issue so as to minimize this problem.

Conclusion

Auricular acupuncture with semipermanent needles in specific points, also known as BFA, provided weekly to patients with below level neuropathic pain due to a chronic spinal cord injury provided clinically meaningful reduction in pain. This pain reduction was significantly better than that seen in delayed entry controls in a repeated measures comparison across an eight week trial with measures at both four and eight weeks. There was also a statistically significant improvement in patient global impression of change in the treatment group compared to the delayed entry control group. Our findings confirm the safety and feasibility of this protocol and can be used to inform the design of larger clinical trials. This study provides proof of concept that a BFA protocol has a clinically meaningful effect on modulation of SCI neuropathic pain.

Acknowledgments

Study consultant: Richard Niemtzow, MD Study acupuncturists: B. Jackson, M. Hsu Study coordinators: D. Taber, M. Zheng, J. Perreault Study physical therapists: K. Romero, J. Stacey, A. Bankard

Disclaimer statements

Funding Paralyzed Veterans of America Research Foundation, Grant # 2806.

Conflicts of interest None.

References

- 1.Dijkers M, Bryce T, Zanca J.. Prevalence of chronic pain after traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Rehabil Res Dev 2009;46(1):13–29. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2008.04.0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardenas DD, Felix ER.. Pain after spinal cord injury: a review of classification, treatment approaches, and treatment assessment. PM R 2009;1(12):1077–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. J Spinal Cord Med 2014;37(5):659–60. doi: 10.1179/1079026814Z.000000000341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estores IM. The consumer's perspective and the professional literature: what do persons with spinal cord injury want? J Rehabil Res Dev 2003;40(4 Suppl 1):93–8. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2003.08.0093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Widerstrom-Noga EG, Turk DC.. Types and effectiveness of treatments used by people with chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: influence of pain and psychosocial characteristics. Spinal Cord 2003;41(11):600–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norrbrink C, Lofgren M, Hunter JP, Ellis J.. Patients’ perspectives on pain. Top iSpinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2012;18(1):50–6. doi: 10.1310/sci1801-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravenscroft A, Ahmed YS, Burnside IG.. Chronic pain after SCI. A patient survey. Spinal Cord 2000;38(10):611–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner JA, Cardenas DD, Warms CA, McClellan CB.. Chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: a community survey. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2001;82(4):501–9. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.21855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy D, Reid DB.. Pain treatment satisfaction in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2001;39(1):44–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardenas DD, Jensen MP.. Treatments for chronic pain in persons with spinal cord injury: a survey study. J Spinal Cord Med 2006;29(2):109–17. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2006.11753864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heo I, Shin BC, Kim YD, Hwang EH, Han CW, Heo KH.. Acupuncture for spinal cord injury and its complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:364216. doi: 10.1155/2013/364216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M.. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther 2003;83(8):713–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyson-Hudson TA, Kadar P, LaFountaine M, Emmons R, Kirshblum SC, Tulsky D, et al. Acupuncture for chronic shoulder pain in persons with spinal cord injury: a small-scale clinical trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88(10):1276–83. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nayak S, Shiflett SC, Schoenberger NE, Agostinelli S, Kirshblum S, Averill A, et al. Is acupuncture effective in treating chronic pain after spinal cord injury? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82(11):1578–86. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.26624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapson LM, Wells N, Pepper J, Majid N, Boon H.. Acupuncture as a promising treatment for below-level central neuropathic pain: a retrospective study. J Spinal Cord Med 2003;26(1):21–6. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2003.11753655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niemtzow Battlefield Acupuncture. Medical Acupuncture. 2007;19(4):225–8. doi: 10.1089/acu.2007.0603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho SY, Jahng GH, Park SU, Jung WS, Moon SK, Park JM.. fMRI study of effect on brain activity according to stimulation method at LI11, ST36: painful pressure and acupuncture stimulation of same acupoints. J Altern Complement Med 2010;16(4):489–95. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hui KK, Marina O, Liu J, Rosen BR, Kwong KK.. Acupuncture, the limbic system, and the anticorrelated networks of the brain. Auton Neurosci 2010;157(1–2):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui KK, Liu J, Marina O, Napadow V, Haselgrove C, Kwong KK, et al. The integrated response of the human cerebro-cerebellar and limbic systems to acupuncture stimulation at ST 36 as evidenced by fMRI. NeuroImage 2005;27(3):479–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui KK, Liu J, Makris N, Gollub RL, Chen AJ, Moore CI, et al. Acupuncture modulates the limbic system and subcortical gray structures of the human brain: evidence from fMRI studies in normal subjects. Hum Brain Mapp 2000;9(1):13–25. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goertz CM, Niemtzow R, Burns SM, Fritts MJ, Crawford CC, Jonas WB.. Auricular acupuncture in the treatment of acute pain syndromes: a pilot study. Mil Med 2006;171(10):1010–4. doi: 10.7205/MILMED.171.10.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romoli M, Allais G, Airola G, Benedetto C, Mana O, Giacobbe M, et al. Ear acupuncture and fMRI: a pilot study for assessing the specificity of auricular points. Neurol Sci 2014;35 Suppl 1:189–93. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1768-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dvorak MF, Wing PC, Fehlings MG, Vaccaro AR, Itshayek E, Biering-Sørensen F, et al. International spinal cord injury spinal column injury basic data set. Spinal Cord 2012;50(11):817–21. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryce TN, Dijkers MP, Ragnarsson KT, Stein AB, Chen B.. Reliability of the Bryce/Ragnarsson spinal cord injury pain taxonomy. J Spinal Cord Med 2006;29(2):118–32. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2006.11753865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2005;113(1–2):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bryce TN, Budh CN, Cardenas DD, Dijkers M, Felix ER, Finnerup NB, et al. Pain after spinal cord injury: an evidence-based review for clinical practice and research. Report of the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Spinal Cord Injury Measures meeting. J Spinal Cord Med 2007;30(5):421–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Farrar JT, Young JP Jr., LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM.. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001;94(2):149–58. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(19):1444–53. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacPherson H, Vertosick E, Lewith G, Linde K, Sherman KJ, Witt CM, et al. Influence of control group on effect size in trials of acupuncture for chronic pain: a secondary analysis of an individual patient data meta-analysis. PloS One 2014;9(4):e93739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langevin HM, Wayne PM, Macpherson H, Schnyer R, Milley RM, Napadow V, et al. Paradoxes in acupuncture research: strategies for moving forward. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011;2011:180805. doi: 10.1155/2011/180805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, Ciapetti A, Grassi W.. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain 2004;8(4):283–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanley MA, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Robinson LR, Cardenas DD, Turner JA, et al. Clinically significant change in pain intensity ratings in persons with spinal cord injury or amputation. Clin J Pain 2006;22(1):25–31. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000148628.69627.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]