Abstract

The versatile and ubiquitous Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen causing acute and chronic infections in predisposed human subjects. Here we review recent progress in understanding P. aeruginosa population biology and virulence, its cyclic di-GMP-mediated switches of lifestyle, and its interaction with the mammalian host as well as the role of the type III and type VI secretion systems in P. aeruginosa infection.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, type III secretion system, T3SS, type VI secretion system, T6SS, c-di-GMP

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a metabolically versatile ubiquitous gamma-proteobacterium that thrives in soil and aquatic habitats and colonizes the animate surfaces of plants, animals, and humans 1. P. aeruginosa may cause multiple infections in man that vary from local to systemic and from benign to life threatening. During the last few decades, the cosmopolitan Gram-negative bacterium has become one of the most frequent causative agents of nosocomial infections associated with substantial morbidity and mortality 2. Pneumonia and sepsis in intensive care unit (ICU) patients still have a bleak prognosis 3. Chronic airway infections with P. aeruginosa are a major cause of morbidity in people with cystic fibrosis (CF) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 3– 5. Here we report on recent advances in the understanding of host–pathogen interactions with particular emphasis on infections with P. aeruginosa in humans.

Differential pathogenicity of clone types

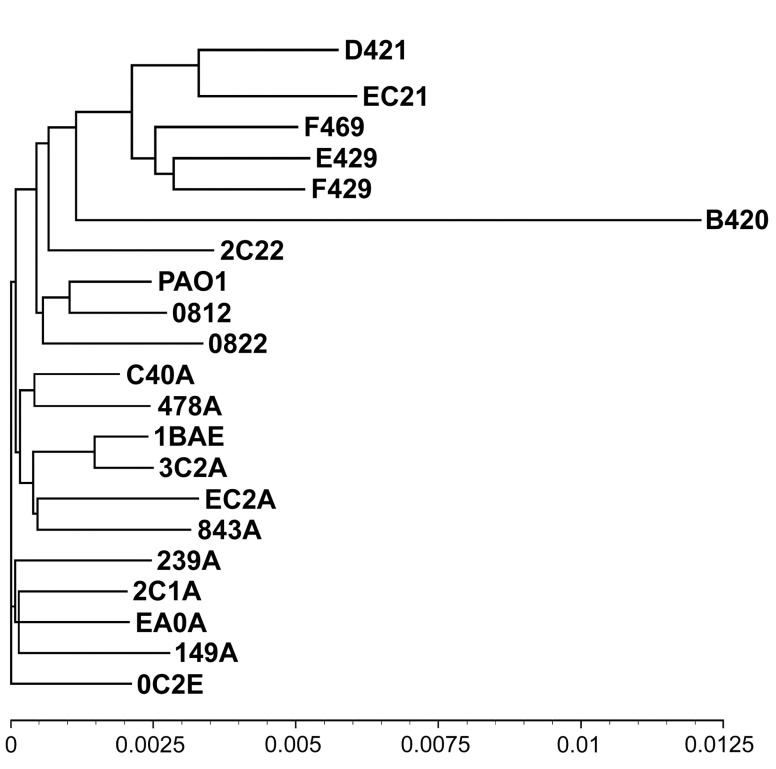

P. aeruginosa is equipped with a large repertoire of virulence determinants ( Table 1) and a complex regulatory network of intracellular and intercellular signals 6, 7 that allow the bacteria to adapt to and thrive in an animate niche and to escape host defence. This ability, however, varies from clone to clone and from strain to strain in the worldwide P. aeruginosa population. When representative isolates of the 20 most common clones in clinical and environmental habitats ( Figure 1) were tested in three established infection models, i.e. an acute infection of murine airways, lettuce, and wax moth larvae, an unexpected gradient of pathogenicity was observed 8. Under the conditions of the standardized acute airway infection model in the mouse, the full spectrum of possible host responses to P. aeruginosa was seen that ranged from unimpaired health to 100% lethality. Likewise, similar gradients of virulence were observed with plant and insect hosts whereby the pathogenicity of most strains differed by host. A strain could be innocuous for the mouse but highly pathogenic for the lettuce, and vice versa.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains representing the 20 most common clones in the global P. aeruginosa population 8, 9.

Clones are designated by a hexadecimal code representing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at seven conserved loci of the core genome and the subtypes of exoU/ exoS and fliC 9. The B420 clone represents the PA7-outlier group, D421, EC21, F469, E429, and F429 the ExoU-positive clade, and all other clones the ExoS-positive clade. The tree is based on paired genome-wide comparisons of SNPs in the core genome 8. The scale indicates the sequence diversity. Reproduced from Figure 5 of 8.

Table 1. Virulence effectors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa *.

| Name | Activity and function |

|---|---|

| ArpA | Alkaline protease, zinc metalloprotease; degrades host immune complements C1q, C2, and C3 and cytokines interferon

(IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α |

| Cif | Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) inhibitory factor, epoxide hydrolase; promotes sustained

inflammation by hydrolysing the paracrine signal 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid that stimulates neutrophils to produce the proresolving lipid mediator 15-epi lipoxin A 4; Cif increases the ubiquitination and lysosomal degradation of some ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC) including CFTR, P-glycoprotein, and TAP1 |

| ExlA | Exolysin A, a pore-forming toxin that induces plasma membrane rupture in epithelial, endothelial, and immune cells |

| ExoS | Bifunctional toxin with Rho GTPase-activating protein (RhoGAP) activity and ADP-ribosyltransferase (ADPRT) activity; it

blocks the reactive oxygen species burst in neutrophils by ADP-ribosylation of Ras, thereby preventing the activation of phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K), which is required to stimulate the phagocytic NADPH-oxidase |

| ExoT | Bifunctional toxin with RhoGAP activity and ADPRT activity; it impairs the production of reactive oxygen species burst

in neutrophils and promotes the apoptosis of host cells by transforming host protein Crk by ADP-ribosylation into a cytotoxin and by activation of the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway |

| ExoU | Phospholipase A

2, releases fatty acids from a broad range of phospholipids and lysophospholipids; it becomes

activated by interaction with ubiquitin or ubiquitinylated proteins in the cytosol of the host cell |

| ExoY | Nucleotidyl cyclase with preference for cGMP and cUMP production; it becomes activated by binding to filamentous

actin |

| LasA | Zinc metalloprotease of the M23A family; it enhances elastolytic activity of LasB |

| LasB | Zinc metalloprotease with strong elastolytic activity |

| PlcH | Haemolytic phospholipase C that releases phosphate esters from sphingomyelin and phosphatidylcholine |

| PlcN | Non-haemolytic phospholipase C that releases phosphate esters from phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylcholine |

| PldA | Trans-kingdom toxin, phospholipase D, facilitates intracellular invasion of host eukaryotic cells by activation of the PI3K/

Akt pathway |

| PldB | Trans-kingdom toxin, phospholipase D, facilitates intracellular invasion of host eukaryotic cells by activation of the PI3K/

Akt pathway |

| PrpL | Class IV protease, lysine endoproteinase, degrades proteins such as complement, immunoglobulins, elastin, lactoferrin,

and transferrin |

| Pyocyanin | Redox-active zwitterion that is cytotoxic |

| Rhamnolipids | Chemically heterogeneous group of monorhamnolipids and dirhamnolipids that are also biosurfactants and cause

haemolysis and lysis of immune effector cells |

| Tox A | Exotoxin A, a toxin with ADPRT activity; it mediates its entry into target host cells through its cell-binding domain, then

ADP-ribosylates host elongation factor 2 (EF-2) to block protein synthesis through its enzymatic domain |

| TplE | Trans-kingdom toxin, phospholipase A1, disrupts the endoplasmic reticulum and thereby promotes autophagy by the

activation of the unfolded protein response |

*The Table lists proven virulence effectors in infections of mammals

The differential genetic repertoire of clones maintains a host-specific gradient of virulence in the P. aeruginosa population whereby differential sets of pathogenicity factors and mechanisms are employed to conquer the diverse animate niches. In other words, the fitness of a clone to colonize and to persist differs by habitat. This conclusion is supported by real-world data. Close to 3,000 spatiotemporally unrelated isolates from the environment, acute human infection, and chronically colonized COPD and CF airways were genotyped with a marker microarray yielding 300-odd clone genotypes 9. The 20 most frequent clones had an absolute share of 44%, indicating that the P. aeruginosa population is dominated by few epidemic clonal lineages. The most abundant clones like C or PA14 were detected in all habitats, albeit at different frequencies 10. On the other hand, the proportion of habitat-specific clones was 25% in COPD, 32% in acute infections, 39% in the environment, and 54% in CF, indicating that the CF lungs select for rare clones that can withstand exposure to a hostile immune system and regular antimicrobial chemotherapy and that the soil and aquatic habitats accommodate a subgroup of clones that cannot colonize a human niche. The spectrum of clones was broader in COPD and CF lungs than in the multiple niches of acute infections, implying that the airways of a predisposed host can be colonized by more clone types than the organs of a previously healthy and immunocompetent host that suffers from an acute insult. In summary, a human habitat can be colonized by some generalists like clone C or PA14 and some minor clones that have a low prevalence in the global population but are endowed with clone-specific features of fitness and/or pathogenicity to become a dominant member in the particular human niche. Since most research has focused on clinical isolates, the analysis of isolates from non-clinical habitats may reveal features yet unknown for P. aeruginosa.

Non-coding RNAs

The Pseudomonas genome database 11 (20 June 2017) lists 37 non-coding RNAs in the genome of reference strain PAO1. These small RNAs (sRNA) have regulatory functions. Prominent examples are RsmY, RsmZ, or CrcZ, which are master regulators of bacterial lifestyle, biofilm formation, and carbon metabolism 12– 15. Recently, the first example of trans-kingdom biological activity of a regulatory P. aeruginosa sRNA was described 16. P. aeruginosa bacteria released outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) containing thousands of unique sRNA fragments. The OMVs fused with and delivered sRNAs into mammalian cells, thereby attenuating neutrophil recruitment and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Type III and type VI secretion systems

The type III secretion system (T3SS) and its effectors are the major virulence determinants of P. aeruginosa 17. The T3SS forms a needle that directly injects virulence effectors (ExoS, T, U, and Y) into the host cell. The ADP-ribosyltransferase (ADPRT) ExoS 18, 19 and the phospholipase A2 ExoU 20, 21 occur almost mutually exclusively in P. aeruginosa so that the population is currently differentiated into a major ExoS-positive clade, a minor ExoU-positive clade, and a minute T3SS-negative clade lacking both ExoS and ExoU 9, 22. ExoU and its homologue PlpD 23, 24, which is secreted through the type V secretion system, are lipolytic enzymes of the patatin-like protein family. ExoU is highly cytotoxic and more virulent than ExoS in infection models, which correlates with the higher morbidity of acute infections with ExoU-positive than with ExoS-positive strains. ExoS and ExoT consist of an N-terminal GTPase-activating protein (GAP) domain and a C-terminal ADPRT domain. Both ExoS and ExoT disrupt the signalling pathway responsible for the activation and assembly of the phagocytic NADPH oxidase and thereby block the production of reactive oxygen species ( Table 1) 25. ExoT moreover promotes the apoptosis of host cells. The GAP domain of ExoT triggers the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway of apoptosis 26, and ADPRT domain activity transforms the focal adhesion adaptor protein Crk of the host cell into a cytotoxin that induces a form of programmed cell death known as anoikis, which occurs in cells when they detach from the surrounding extracellular matrix 27. The pathogenicity of ExoS, ExoU, and ExoT is well established, but the role of ExoY during infections still needs to be elucidated 28– 31. ExoY synthesizes numerous cyclic nucleotides (cNMPs) 32. The uncommon cUMP turned out to be the most prominent cNMP generated in the lungs of mice infected with ExoY overexpressing P. aeruginosa. cUMP was detectable in body fluids, suggesting that this unusual cNMP in contrast to cAMP or cGMP is not rapidly degraded and thus may interfere with the second messenger signalling of the host.

The T3SS-negative clade represents three groups of taxonomic outliers with above-average sequence diversity 8, 22, 33. This, however, does not imply that these strains are innocuous. Firstly, isolates have transferred genomic islands to major ExoS-positive clonal lineages and thereby supplied the recipients with determinants of resistance to antimicrobials 34. Secondly, some strains harbour the recently discovered two-partner secretion system ExlAB 35, 36. ExlB exports a pore-forming toxin called exolysin (ExlA), which induces plasma membrane rupture in epithelial, endothelial, and immune cells but not in erythrocytes. Thirdly, these outliers, like all other ExoS- or ExoU-positive P. aeruginosa strains, possess type VI secretion systems (T6SS).

The T6SS is a bacterial nanomachine that shares similarity with the puncturing device of bacteriophages 37, 38. The three separate H1-, H2-, and H3-T6SS translocate proteins between cells by a mechanism analogous to phage tail contraction. The H1-T6SS delivers the three toxins Tse1–3, which kill bacterial competitors inhabiting the same niche. The H2- and H3-T6SS target both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, i.e. they translocate trans-kingdom effectors 39– 44. These toxins exert antibacterial activity and facilitate intracellular invasion of host eukaryotic cells ( Table 1). The phospholipase TplE, for example, disrupts the endoplasmic reticulum and thereby promotes autophagy by the activation of the unfolded protein response 40, 42– 44.

Control of lifestyle by cyclic di-GMP signalling

P. aeruginosa can switch between a motile and a sessile lifestyle and can modulate the secretion of virulence effectors by a plethora of transcription factors, two-component systems, non-coding RNAs, and quorum-sensing networks 6, 45. Research in the last few years has focused on the complex signalling pathways mediated by the second messenger cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) 46, 47. P. aeruginosa possesses more than 40 diguanylate cyclases and c-di-GMP-degrading phosphodiesterases, the specificities of which are currently under investigation 46, 47.

Elevated levels of c-di-GMP promote biofilm formation typical for chronic infections and repress flagellum-driven swarming motility typical for acute infections and vice versa. The master transcription regulator FleQ, for example, activates the transcription of flagellar genes when intracellular c-di-GMP levels are low, but upon binding of c-di-GMP FleQ converts to an activator of the expression of genes involved in biofilm formation such as the adhesin CdrAB or the exopolysaccharides Psl and Pel 48, 49. The binding of c-di-GMP leads to major conformational rearrangements in FleQ, which reasonably explains the dual role of FleQ in promoting both the sessile and the motile lifestyles dependent on c-di-GMP levels.

The third major exopolysaccharide in P. aeruginosa biofilms is alginate, a polymer of mannuronic and guluronic acid. Alginate secretion is promoted by the protein Alg44 upon the binding of two c-di-GMP molecules 50. The production of alginate is induced under microaerophilic or anaerobic conditions, as is typically the case for chronic infections of COPD and CF lungs 51. A recently discovered three-gene operon, sadC-odaA-odaI, controls the oxygen-dependent synthesis of alginate 52. During anaerobiosis, the diguanylate cyclase SadC produces c-di-GMP, but in the presence of oxygen OdaI inhibits c-di-GMP synthesis by SadC 52. Besides the induction of alginate biosynthesis, SadC inhibits swimming, swarming, and twitching motility, promotes the production of the exopolysaccharide Psl, and is a member of the RetS/LadS/Gac/Rsm regulatory network that constitutes the decision-making switch between sessile and motile lifestyles 53, 54.

The transition from the biofilm to the planktonic growth state is under the complex regulatory control of many other players influencing the intracellular c-di-GMP levels. The chemosensory protein BdlA, the diguanylate cyclase GcbA, and the c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases DipA, RbdA, and NbdA are known proteins that are required for dispersion to occur 55– 57.

Within-host evolution of P. aeruginosa

P. aeruginosa may persist for decades in the lungs of individuals with CF, which provides the rare opportunity to study the within-host evolution of a bacterial pathogen for an extended period of time 58. A single case who acquired P. aeruginosa in the neonatal period has already been analysed by whole genome sequencing of serial P. aeruginosa isolates more than 10 years ago 59. Subsequently, the genetic adaptation of P. aeruginosa to CF lungs has been investigated in carriers of major clones 60 or transmissible lineages 61– 65 and, more recently, in a cohort of CF children who were followed for the early phase of infection 66. This study of 474 longitudinal isolates from 34 CF patients seen at the Copenhagen CF clinic, representing 36 different clonal lineages of P. aeruginosa, showed evidence for positive selection at 52 genes, suggesting adaptive evolution to optimise pathogen fitness. Numerous genes encode traits known to be involved in CF lung infection, such as antibiotic resistance or biofilm formation. In our own ongoing work on serial P. aeruginosa isolates from patients seen at the Hannover CF clinic, we rediscovered just a quarter of these 52 candidate pathoadaptive genes to be frequently mutated, demonstrating the versatility of P. aeruginosa to conquer and persist in CF airways. This versatility also shows up in an extensive phenotypic diversity within the P. aeruginosa populations inhabiting CF airways. The analysis of 15 variable traits in 1,720 isolates collected from 10 carriers of the Liverpool epidemic strain revealed 398 unique subtypes 67. In summary, all of these cross-sectional and longitudinal studies demonstrated extensive genetic and phenotypic diversity of the P. aeruginosa populations in CF lungs 58– 72.

The response of the mammalian immune system to P. aeruginosa

Innate immune defence molecules 73, 74, CD95-mediated apoptosis of epithelial cells 75, 76, and killing by polymorphonuclear neutrophilic granulocytes (PMNs) 77 play critical roles in fighting P. aeruginosa. PMNs are primarily recruited by chemokines to the diseased microenvironment. Upon chemokine binding, the chemokine receptor CXCR2 mediates the migration of the neutrophil to sites of inflammation and the chemokine receptor CXCR1 stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species to kill the P. aeruginosa bacteria 78. The clearance of the bacteria, however, should not be accompanied by excessive and systemic inflammation. Recent studies on the cytokines of the interleukin-17 (IL-17) family highlighted this delicate balance between antibacterial host response and inflammation-triggered organ pathology 79– 81. Through the use of a chronic murine pulmonary infection model, IL-17 cytokine signalling was found to be essential for mouse survival and the prevention of chronic infection with P. aeruginosa 79. On the other hand, IL-17A deficiency protected mice from an acute lethal P. aeruginosa lung infection 80. In the lung, IL-17A is released from numerous T-cell subtypes, innate lymphoid cells, and macrophages. IL-17A recruits inflammatory cells, but it also activates the airway epithelium to produce IL-17C. IL-17C increases the release of neutrophilic cytokines from alveolar epithelium and thus amplifies inflammation 81. IL-17C production is also directly induced by P. aeruginosa. Thus, epithelial cells activated by both the pathogen and the professional immune cells contribute to local and systemic inflammation during P. aeruginosa infection 81.

The IL-17 story demonstrates the context-dependent, subtle balance of harm and benefit of host defence mechanisms against P. aeruginosa. The ongoing race between pathogen and host has also resulted in highly specific host responses to individual bacterial components and vice versa. Some key mechanisms have recently been elucidated.

The secondary metabolite phenazine, for example, is recognised by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor AhR that triggers the recruitment of PMNs to the site of the bacterial insult 82, whereas the secondary metabolite pyocyanin induces the release of reactive oxygen species from mitochondria, which promotes the death of PMNs 83. These key cells of host defence not only eliminate P. aeruginosa by phagocytic killing but also trap and kill the microbes by neutrophilic extracellular traps (NETs), which are made up of DNA as the scaffold and neutrophilic granule components such as neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase 84, 85. The flagellum has been shown to be the main bacterial organelle that induces NET formation and thus triggers inflammation 86. Early growth phase P. aeruginosa are the strongest NET inducers. On the other hand, flagellar motility is downregulated and the flagellum is even lost during the course of chronic lung infections so that P. aeruginosa evades NET-mediated killing 86– 88.

If P. aeruginosa conquers a mammalian niche, it delivers the T3SS effector molecule ExoS directly into the cytosol of the host cell. In a mouse pneumonia model, phagocytes were targeted for injection of ExoS early during infection followed by injection of epithelial cells at later time points so that finally the pulmonary–vascular barrier was disrupted 89. This mechanism of stepwise inactivation of host defence cells first and the epithelial barrier thereafter makes it plausible that P. aeruginosa bacteria in the lung can gain access to the bloodstream and cause sepsis.

Looking back forward

P. aeruginosa has been and still is one of the medically most relevant opportunistic pathogens in man 2, 90, 91. The management of eye 92 and burn wound 93, 94 infections has made considerable progress, but the acute 95 and chronic 4, 5, 95– 99 pulmonary infections continue to be associated with substantial morbidity and mortality.

Thanks to the application of omics technologies, we have gained insight into P. aeruginosa’s genome organisation and diversity 8, 10, 11, 22, 100, habitat-specific transcriptome 101– 105, proteome 106– 108, and metabolome 108– 112 and the co-evolution of P. aeruginosa with competitors in human habitats such as Staphylococcus aureus 113– 115. The function of hundreds of previously uncharacterised “conserved hypotheticals” 11 and the structure of secretory nanomachines have been resolved 37, 41, 116– 121 and knowledge has been gained about the complex regulation of the release of exopolysaccharides, secondary metabolites, and virulence effectors 1. In other words, during the last few years, we have learnt a lot about the modules of bacterial pathogenicity 1, 122. In contrast, progress has been rather slow in the field of antipseudomonal host defence. The mechanisms that mediate bacterial clearance without causing excessive immune pathology deserve further investigation if we want to improve the management of Pseudomonas pneumonia and sepsis 123– 126. P. aeruginosa is an extremely versatile microorganism, and it will continue to surprise us with as-yet-unappreciated modes of niche adaptation, lifestyle, and pathogenicity.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Ina Attrée, Université Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France

Jürgen Heesemann, Max von Pettenkofer-Institute, Ludwig Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany

Craig Winstanley, Institute of Infection and Global Health, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

Funding Statement

The authors’ work on P. aeruginosa genomics, microevolution, and pathogenicity has been supported by the Bundesministerium für Forschung und Technologie BMBF (FKZ 0315827D) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 900, projects A2 and Z1).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; referees: 3 approved]

References

- 1. Ramos JL.(ed.): Pseudomonas.Heidelberg: Springer;2004; 1–7 10.1007/978-1-4419-9086-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buhl M, Peter S, Willmann M: Prevalence and risk factors associated with colonization and infection of extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a systematic review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13(9):1159–70. 10.1586/14787210.2015.1064310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque CF, Silva AR, Burth P, et al. : Possible mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-associated lung disease. Int J Med Microbiol. 2016;306(1):20–8. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Talwalkar JS, Murray TS: The Approach to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Cystic Fibrosis. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37(1):69–81. 10.1016/j.ccm.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murphy TF: Pseudomonas aeruginosa in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15(2):138–42. 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328321861a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Balasubramanian D, Schneper L, Kumari H, et al. : A dynamic and intricate regulatory network determines Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(1):1–20. 10.1093/nar/gks1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reinhart AA, Oglesby-Sherrouse AG: Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence by Distinct Iron Sources. Genes (Basel). 2016;7(12): pii: E126. 10.3390/genes7120126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hilker R, Munder A, Klockgether J, et al. : Interclonal gradient of virulence in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa pangenome from disease and environment. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17(1):29–46. 10.1111/1462-2920.12606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiehlmann L, Cramer N, Tümmler B: Habitat-associated skew of clone abundance in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa population. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2015;7(6):955–60. 10.1111/1758-2229.12340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fischer S, Klockgether J, Morán Losada P, et al. : Intraclonal genome diversity of the major Pseudomonas aeruginosa clones C and PA14. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2016;8(2):227–34. 10.1111/1758-2229.12372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Winsor GL, Griffiths EJ, Lo R, et al. : Enhanced annotations and features for comparing thousands of Pseudomonas genomes in the Pseudomonas genome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D646–53. 10.1093/nar/gkv1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sonnleitner E, Haas D: Small RNAs as regulators of primary and secondary metabolism in Pseudomonas species. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;91(1):63–79. 10.1007/s00253-011-3332-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sonnleitner E, Bläsi U: Regulation of Hfq by the RNA CrcZ in Pseudomonas aeruginosa carbon catabolite repression. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(6):e1004440. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pusic P, Tata M, Wolfinger MT, et al. : Cross-regulation by CrcZ RNA controls anoxic biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep. 2016;6: 39621. 10.1038/srep39621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chambonnier G, Roux L, Redelberger D, et al. : The Hybrid Histidine Kinase LadS Forms a Multicomponent Signal Transduction System with the GacS/GacA Two-Component System in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(5):e1006032. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koeppen K, Hampton TH, Jarek M, et al. : A Novel Mechanism of Host-Pathogen Interaction through sRNA in Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(6):e1005672. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 17. Galle M, Carpentier I, Beyaert R: Structure and function of the Type III secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2012;13(8):831–42. 10.2174/138920312804871210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berube BJ, Rangel SM, Hauser AR: Pseudomonas aeruginosa: breaking down barriers. Curr Genet. 2016;62(1):109–13. 10.1007/s00294-015-0522-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Engel J, Balachandran P: Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III effectors in disease. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12(1):61–6. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sato H, Frank DW: ExoU is a potent intracellular phospholipase. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53(5):1279–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sawa T, Hamaoka S, Kinoshita M, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type III Secretory Toxin ExoU and Its Predicted Homologs. Toxins (Basel). 2016;8(11): pii: E307. 10.3390/toxins8110307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Freschi L, Jeukens J, Kukavica-Ibrulj I, et al. : Clinical utilization of genomics data produced by the international Pseudomonas aeruginosa consortium. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1036. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salacha R, Kovacić F, Brochier-Armanet C, et al. : The Pseudomonas aeruginosa patatin-like protein PlpD is the archetype of a novel Type V secretion system. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12(6):1498–512. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. da Mata Madeira PV, Zouhir S, Basso P, et al. : Structural Basis of Lipid Targeting and Destruction by the Type V Secretion System of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(9 Pt A):1790–803. 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vareechon C, Zmina SE, Karmakar M, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa Effector ExoS Inhibits ROS Production in Human Neutrophils. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21(5):611–618.e5. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 26. Wood SJ, Goldufsky JW, Bello D, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT Induces Mitochondrial Apoptosis in Target Host Cells in a Manner That Depends on Its GTPase-activating Protein (GAP) Domain Activity. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(48):29063–73. 10.1074/jbc.M115.689950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 27. Wood S, Goldufsky J, Shafikhani SH: Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT Induces Atypical Anoikis Apoptosis in Target Host Cells by Transforming Crk Adaptor Protein into a Cytotoxin. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(5):e1004934. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 28. Yahr TL, Vallis AJ, Hancock MK, et al. : ExoY, an adenylate cyclase secreted by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(23):13899–904. 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morrow KA, Seifert R, Kaever V, et al. : Heterogeneity of pulmonary endothelial cyclic nucleotide response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoY infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309(10):L1199–207. 10.1152/ajplung.00165.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morrow KA, Ochoa CD, Balczon R, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzymes U and Y induce a transmissible endothelial proteinopathy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;310(4):L337–53. 10.1152/ajplung.00103.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Belyy A, Raoux-Barbot D, Saveanu C, et al. : Actin activates Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoY nucleotidyl cyclase toxin and ExoY-like effector domains from MARTX toxins. Nat Commun. 2016;7: 13582. 10.1038/ncomms13582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bähre H, Hartwig C, Munder A, et al. : cCMP and cUMP occur in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;460(4):909–14. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.03.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huber P, Basso P, Reboud E, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa renews its virulence factors. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2016;8(5):564–571. 10.1111/1758-2229.12443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thrane SW, Taylor VL, Freschi L, et al. : The Widespread Multidrug-Resistant Serotype O12 Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clone Emerged through Concomitant Horizontal Transfer of Serotype Antigen and Antibiotic Resistance Gene Clusters. MBio. 2015;6(5):e01396–15. 10.1128/mBio.01396-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 35. Elsen S, Huber P, Bouillot S, et al. : A type III secretion negative clinical strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa employs a two-partner secreted exolysin to induce hemorrhagic pneumonia. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(2):164–76. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 36. Reboud E, Elsen S, Bouillot S, et al. : Phenotype and toxicity of the recently discovered exlA-positive Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains collected worldwide. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18(10):3425–39. 10.1111/1462-2920.13262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 37. Chen L, Zou Y, She P, et al. : Composition, function, and regulation of T6SS in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Res. 2015;172:19–25. 10.1016/j.micres.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lin J, Cheng J, Chen K, et al. : The icmF3 locus is involved in multiple adaptation- and virulence-related characteristics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;5:70. 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jiang F, Waterfield NR, Yang J, et al. : A Pseudomonas aeruginosa type VI secretion phospholipase D effector targets both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(5):600–10. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hu H, Zhang H, Gao Z, et al. : Structure of the type VI secretion phospholipase effector Tle1 provides insight into its hydrolysis and membrane targeting. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70(Pt 8):2175–85. 10.1107/S1399004714012899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang XY, Li ZQ, She Z, et al. : Structural analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa H3-T6SS immunity proteins. FEBS Lett. 2016;590(16):2787–96. 10.1002/1873-3468.12291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Flaugnatti N, Le TT, Canaan S, et al. : A phospholipase A 1 antibacterial Type VI secretion effector interacts directly with the C-terminal domain of the VgrG spike protein for delivery. Mol Microbiol. 2016;99(6):1099–118. 10.1111/mmi.13292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jiang F, Wang X, Wang B, et al. : The Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type VI Secretion PGAP1-like Effector Induces Host Autophagy by Activating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Cell Rep. 2016;16(6):1502–9. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bleves S: Game of Trans-Kingdom Effectors. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(10):773–4. 10.1016/j.tim.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jimenez PN, Koch G, Thompson JA, et al. : The multiple signaling systems regulating virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76(1):46–65. 10.1128/MMBR.05007-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 46. Ha DG, O'Toole GA: c-di-GMP and its Effects on Biofilm Formation and Dispersion: a Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Review. Microbiol Spectr. 2015;3(2): MB-0003-2014. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MB-0003-2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Valentini M, Filloux A: Biofilms and Cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) Signaling: Lessons from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Other Bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(24):12547–55. 10.1074/jbc.R115.711507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baraquet C, Harwood CS: FleQ DNA Binding Consensus Sequence Revealed by Studies of FleQ-Dependent Regulation of Biofilm Gene Expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2015;198(1):178–86. 10.1128/JB.00539-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 49. Matsuyama BY, Krasteva PV, Baraquet C, et al. : Mechanistic insights into c-di-GMP-dependent control of the biofilm regulator FleQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(2):E209–18. 10.1073/pnas.1523148113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 50. Whitney JC, Whitfield GB, Marmont LS, et al. : Dimeric c-di-GMP is required for post-translational regulation of alginate production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(20):12451–62. 10.1074/jbc.M115.645051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Worlitzsch D, Tarran R, Ulrich M, et al. : Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(3):317–25. 10.1172/JCI13870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schmidt A, Hammerbacher AS, Bastian M, et al. : Oxygen-dependent regulation of c-di-GMP synthesis by SadC controls alginate production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18(10):3390–402. 10.1111/1462-2920.13208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moscoso JA, Jaeger T, Valentini M, et al. : The diguanylate cyclase SadC is a central player in Gac/Rsm-mediated biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2014;196(23):4081–8. 10.1128/JB.01850-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhu B, Liu C, Liu S, et al. : Membrane association of SadC enhances its diguanylate cyclase activity to control exopolysaccharides synthesis and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18(10):3440–52. 10.1111/1462-2920.13263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 55. Basu Roy A, Sauer K: Diguanylate cyclase NicD-based signalling mechanism of nutrient-induced dispersion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2014;94(4):771–93. 10.1111/mmi.12802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li Y, Petrova OE, Su S, et al. : BdlA, DipA and induced dispersion contribute to acute virulence and chronic persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(6):e1004168. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Petrova OE, Cherny KE, Sauer K: The diguanylate cyclase GcbA facilitates Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm dispersion by activating BdlA. J Bacteriol. 2015;197(1):174–87. 10.1128/JB.02244-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 58. Winstanley C, O'Brien S, Brockhurst MA: Pseudomonas aeruginosa Evolutionary Adaptation and Diversification in Cystic Fibrosis Chronic Lung Infections. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(5):327–37. 10.1016/j.tim.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Smith EE, Buckley DG, Wu Z, et al. : Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(22):8487–92. 10.1073/pnas.0602138103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 60. Cramer N, Klockgether J, Wrasman K, et al. : Microevolution of the major common Pseudomonas aeruginosa clones C and PA14 in cystic fibrosis lungs. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13(7):1690–704. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02483.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yang L, Jelsbak L, Marvig RL, et al. : Evolutionary dynamics of bacteria in a human host environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(18):7481–6. 10.1073/pnas.1018249108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 62. Marvig RL, Johansen HK, Molin S, et al. : Genome analysis of a transmissible lineage of pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals pathoadaptive mutations and distinct evolutionary paths of hypermutators. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(9):e1003741. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 63. Williams D, Evans B, Haldenby S, et al. : Divergent, coexisting Pseudomonas aeruginosa lineages in chronic cystic fibrosis lung infections. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(7):775–85. 10.1164/rccm.201409-1646OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dettman JR, Rodrigue N, Aaron SD, et al. : Evolutionary genomics of epidemic and nonepidemic strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(52):21065–70. 10.1073/pnas.1307862110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sherrard LJ, Tai AS, Wee BA, et al. : Within-host whole genome analysis of an antibiotic resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain sub-type in cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172179. 10.1371/journal.pone.0172179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Marvig RL, Sommer LM, Molin S, et al. : Convergent evolution and adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa within patients with cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2015;47(1):57–64. 10.1038/ng.3148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 67. Mowat E, Paterson S, Fothergill JL, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa population diversity and turnover in cystic fibrosis chronic infections. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(12):1674–9. 10.1164/rccm.201009-1430OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Workentine ML, Sibley CD, Glezerson B, et al. : Phenotypic heterogeneity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations in a cystic fibrosis patient. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60225. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Clark ST, Diaz Caballero J, Cheang M, et al. : Phenotypic diversity within a Pseudomonas aeruginosa population infecting an adult with cystic fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10932. 10.1038/srep10932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Marvig RL, Sommer LM, Jelsbak L, et al. : Evolutionary insight from whole-genome sequencing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. Future Microbiol. 2015;10(4):599–611. 10.2217/fmb.15.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Andersen SB, Marvig RL, Molin S, et al. : Long-term social dynamics drive loss of function in pathogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(34):10756–61. 10.1073/pnas.1508324112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jorth P, Staudinger BJ, Wu X, et al. : Regional Isolation Drives Bacterial Diversification within Cystic Fibrosis Lungs. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18(3):307–19. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 73. Wnorowska U, Niemirowicz K, Myint M, et al. : Bactericidal activities of cathelicidin LL-37 and select cationic lipids against the hypervirulent Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain LESB58. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(7):3808–15. 10.1128/AAC.00421-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wonnenberg B, Bischoff M, Beisswenger C, et al. : The role of IL-1β in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in lung infection. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;364(2):225–9. 10.1007/s00441-016-2387-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Grassmé H, Kirschnek S, Riethmueller J, et al. : CD95/CD95 ligand interactions on epithelial cells in host defense to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science. 2000;290(5491):527–30. 10.1126/science.290.5491.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Grassmé H, Jendrossek V, Riehle A, et al. : Host defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires ceramide-rich membrane rafts. Nat Med. 2003;9(3):322–30. 10.1038/nm823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 77. Lovewell RR, Patankar YR, Berwin B: Mechanisms of phagocytosis and host clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306(7):L591–603. 10.1152/ajplung.00335.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Carevic M, Öz H, Fuchs K, et al. : CXCR1 Regulates Pulmonary Anti- Pseudomonas Host Defense. J Innate Immun. 2016;8(4):362–73. 10.1159/000444125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 79. Bayes HK, Ritchie ND, Evans TJ: Interleukin-17 Is Required for Control of Chronic Lung Infection Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 2016;84(12):3507–16. 10.1128/IAI.00717-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 80. Wonnenberg B, Jungnickel C, Honecker A, et al. : IL-17A attracts inflammatory cells in murine lung infection with P. aeruginosa. Innate Immun. 2016;22(8):620–5. 10.1177/1753425916668244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 81. Wolf L, Sapich S, Honecker A, et al. : IL-17A-mediated expression of epithelial IL-17C promotes inflammation during acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;311(5):L1015–L1022. 10.1152/ajplung.00158.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 82. Moura-Alves P, Faé K, Houthuys E, et al. : AhR sensing of bacterial pigments regulates antibacterial defence. Nature. 2014;512(7515):387–92. 10.1038/nature13684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 83. Managò A, Becker KA, Carpinteiro A, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyocyanin induces neutrophil death via mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial acid sphingomyelinase. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;22(13):1097–110. 10.1089/ars.2014.5979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. : Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–5. 10.1126/science.1092385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 85. Yoo DG, Floyd M, Winn M, et al. : NET formation induced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates measured as release of myeloperoxidase-DNA and neutrophil elastase-DNA complexes. Immunol Lett. 2014;160(2):186–94. 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Floyd M, Winn M, Cullen C, et al. : Swimming Motility Mediates the Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Induced by Flagellated Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(11):e1005987. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 87. Young RL, Malcolm KC, Kret JE, et al. : Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET)-mediated killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence of acquired resistance within the CF airway, independent of CFTR. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e23637. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Luzar MA, Thomassen MJ, Montie TC: Flagella and motility alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from patients with cystic fibrosis: relationship to patient clinical condition. Infect Immun. 1985;50(2):577–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Rangel SM, Diaz MH, Knoten CA, et al. : The Role of ExoS in Dissemination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during Pneumonia. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(6):e1004945. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 90. Kaye KS, Pogue JM: Infections Caused by Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: Epidemiology and Management. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(10):949–62. 10.1002/phar.1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Oliver A, Mulet X, López-Causapé C, et al. : The increasing threat of Pseudomonas aeruginosa high-risk clones. Drug Resist Updat. 2015;21–22:41–59. 10.1016/j.drup.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Willcox MD: Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and inflammation during contact lens wear: a review. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(4):273–8. 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3180439c3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, et al. : Burn wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(2):403–34. 10.1128/CMR.19.2.403-434.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Fournier A, Voirol P, Krähenbühl M, et al. : Antibiotic consumption to detect epidemics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a burn centre: A paradigm shift in the epidemiological surveillance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa nosocomial infections. Burns. 2016;42(3):564–70. 10.1016/j.burns.2015.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bassi GL, Ferrer M, Marti JD, et al. : Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(4):469–81. 10.1055/s-0034-1384752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Novosad SA, Barker AF: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19(2):133–9. 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835d8312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Döring G, Parameswaran IG, Murphy TF: Differential adaptation of microbial pathogens to airways of patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35(1):124–46. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Langan KM, Kotsimbos T, Peleg AY: Managing Pseudomonas aeruginosa respiratory infections in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015;28(6):547–56. 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Elborn JS: Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2016;388(10059):2519–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00576-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Klockgether J, Cramer N, Wiehlmann L, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa Genomic Structure and Diversity. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:150. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Wurtzel O, Yoder-Himes DR, Han K, et al. : The single-nucleotide resolution transcriptome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in body temperature. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(9):e1002945. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 102. Turner KH, Everett J, Trivedi U, et al. : Requirements for Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute burn and chronic surgical wound infection. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(7):e1004518. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Dötsch A, Schniederjans M, Khaledi A, et al. : The Pseudomonas aeruginosa Transcriptional Landscape Is Shaped by Environmental Heterogeneity and Genetic Variation. MBio. 2015;6(4):e00749. 10.1128/mBio.00749-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kruczek C, Kottapalli KR, Dissanaike S, et al. : Major Transcriptome Changes Accompany the Growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Blood from Patients with Severe Thermal Injuries. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149229. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Karna SL, D'Arpa P, Chen T, et al. : RNA-Seq Transcriptomic Responses of Full-Thickness Dermal Excision Wounds to Pseudomonas aeruginosa Acute and Biofilm Infection. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165312. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kamath KS, Pascovici D, Penesyan A, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cell Membrane Protein Expression from Phenotypically Diverse Cystic Fibrosis Isolates Demonstrates Host-Specific Adaptations. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(7):2152–63. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Krueger J, Pohl S, Preusse M, et al. : Unravelling post-transcriptional PrmC-dependent regulatory mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18(10):3583–92. 10.1111/1462-2920.13435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Lassek C, Berger A, Zühlke D, et al. : Proteome and carbon flux analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from different infection sites. Proteomics. 2016;16(9):1381–5. 10.1002/pmic.201500228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Frimmersdorf E, Horatzek S, Pelnikevich A, et al. : How Pseudomonas aeruginosa adapts to various environments: a metabolomic approach. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12(6):1734–47. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Behrends V, Bell TJ, Liebeke M, et al. : Metabolite profiling to characterize disease-related bacteria: gluconate excretion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants and clinical isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(21):15098–109. 10.1074/jbc.M112.442814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Tielen P, Rosin N, Meyer AK, et al. : Regulatory and metabolic networks for the adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to urinary tract-like conditions. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71845. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Okon E, Dethlefsen S, Pelnikevich A, et al. : Key role of an ADP - ribose - dependent transcriptional regulator of NAD metabolism for fitness and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Med Microbiol. 2017;307(1):83–94. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Limoli DH, Whitfield GB, Kitao T, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa Alginate Overproduction Promotes Coexistence with Staphylococcus aureus in a Model of Cystic Fibrosis Respiratory Infection. MBio. 2017;8(2): pii: e00186-17. 10.1128/mBio.00186-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 114. Tognon M, Köhler T, Gdaniec BG, et al. : Co-evolution with Staphylococcus aureus leads to lipopolysaccharide alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ISME J. 2017. 10.1038/ismej.2017.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 115. Noto MJ, Burns WJ, Beavers WN, et al. : Mechanisms of pyocyanin toxicity and genetic determinants of resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2017; pii: JB.00221-17. 10.1128/JB.00221-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 116. Koo J, Lamers RP, Rubinstein JL, et al. : Structure of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type IVa Pilus Secretin at 7.4 Å. Structure. 2016;24(10):1778–87. 10.1016/j.str.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 117. Izoré T, Perdu C, Job V, et al. : Structural characterization and membrane localization of ExsB from the type III secretion system (T3SS) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Mol Biol. 2011;413(1):236–46. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Gendrin C, Contreras-Martel C, Bouillot S, et al. : Structural basis of cytotoxicity mediated by the type III secretion toxin ExoU from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(4):e1002637. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Discola KF, Förster A, Boulay F, et al. : Membrane and chaperone recognition by the major translocator protein PopB of the type III secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(6):3591–601. 10.1074/jbc.M113.517920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Lu D, Shang G, Zhang H, et al. : Structural insights into the T6SS effector protein Tse3 and the Tse3-Tsi3 complex from Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveal a calcium-dependent membrane-binding mechanism. Mol Microbiol. 2014;92(5):1092–112. 10.1111/mmi.12616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Ge P, Scholl D, Leiman PG, et al. : Atomic structures of a bactericidal contractile nanotube in its pre- and postcontraction states. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(5):377–82. 10.1038/nsmb.2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 122. Lorenz A, Pawar V, Häussler S, et al. : Insights into host-pathogen interactions from state-of-the-art animal models of respiratory Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. FEBS Lett. 2016;590(21):3941–59. 10.1002/1873-3468.12454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Micek ST, Wunderink RG, Kollef MH, et al. : An international multicenter retrospective study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa nosocomial pneumonia: impact of multidrug resistance. Crit Care. 2015;19:219. 10.1186/s13054-015-0926-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Micek ST, Kollef MH, Torres A, et al. : Pseudomonas aeruginosa nosocomial pneumonia: impact of pneumonia classification. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(10):1190–7. 10.1017/ice.2015.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Cillóniz C, Gabarrús A, Ferrer M, et al. : Community-Acquired Pneumonia Due to Multidrug- and Non-Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chest. 2016;150(2):415–25. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Fernández-Barat L, Ferrer M, de Rosa F, et al. : Intensive care unit-acquired pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa with and without multidrug resistance. J Infect. 2017;74(2):142–52. 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]