Abstract

Introduction

The lateral and third ventricles, as well as the corpus callosum (CC), are known to be affected in schizophrenia. Here we investigate whether abnormalities in the lateral ventricles (LVs), third ventricle, and corpus callosum are related to one another in first episode schizophrenia (FESZ), and whether such abnormalities show progression over time.

Methods

Nineteen FESZ and 19 age- and handedness-matched controls were included in the study. MR images were acquired on a 3-Tesla MRI at baseline and ~1.2 years later. FreeSurfer v.5.3 was employed for segmentation. Two-way or univariate ANCOVAs were used for statistical analysis, where the covariate was intracranial volume. Group and gender were included as between-subjects factors. Percent volume changes between baseline and follow-up were used to determine volume changes at follow-up.

Results

Bilateral LV and third ventricle volumes were significantly increased, while central CC volume was significantly decreased in patients compared to controls at baseline and at follow-up. In FESZ, the bilateral LV volume was also inversely correlated with volume of the central CC. This inverse correlation was not present in controls. In FESZ, an inverse correlation was found between percent volume increase from baseline to follow-up for bilateral LVs and lesser improvement in the Global Assessment of Functioning score.

Conclusions

Significant correlations were observed for abnormalities of central CC, LVs and third ventricle volumes in FESZ, suggesting a common neurodevelopmental origin in schizophrenia. Enlargement of ventricles was associated with less improvement in global functioning over time.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, ventricles, corpus callosum, neurodevelopment, Multi-atlas brain masking, FreeSurfer

Background

Increases in the volume of lateral ventricles (LVs) were among the first identified abnormalities in schizophrenia (Johnstone et al., 1976) and since that time increases in LVs volume remain among the most reliable volumetric abnormalities reported in schizophrenia (Kempton et al., 2010; Nakamura et al., 2007; Shenton et al., 2001). Such increases are present not only in chronic schizophrenia patients but also in the early stages of disease (Nakamura et al., 2007; Shenton et al., 2001). Changes in the corpus callosum (CC) are also described in schizophrenia, where the midsagittal area of the CC has been reported to be decreased in schizophrenia patients (Woodruff et al., 1995), with effects more detectable in first episode than chronic schizophrenia (Arnone et al., 2008). The diffusion tensor imaging significance of CC changes is being actively investigated (Fitzsimmons et al., 2013) (Whitford et al., 2012) (Kubicki and Shenton, 2015).

The CC is the largest white matter tract in the brain and is essential in facilitating communication between the left and right brain. Anatomically and developmentally it is close to the LVs. The tapetum portion of the CC, which includes most of the fibers connecting the left and right hemisphere, covers the central portion of the LVs. The roof of the occipital horn of the LV is formed by the fibers of the CC that pass to the temporal and occipital lobes. The occipital horns are shaped, in part, by myelination of the ventricular walls and association fibers of the CC. There is also close proximity between the CC and the third ventricle, as this ventricle rests on a narrow fissure below the CC (Lazo, 2014).

Although the ventricular system and the corpus callosum are anatomically intimately connected, and share a common genetic background (Pfefferbaum et al., 2000), no studies, to our knowledge, have explored the possibility that the ventricular system and the corpus callosum volume abnormalities are related in the early phase of schizophrenia.

Here we sought to identify co-variation in volume between the corpus callosum (CC) and the ventricles, and their correlations with clinical data in the early schizophrenia disease state. We studied first episode patients and age- and handedness-matched healthy controls at baseline and approximately 1.2-year follow-up.

Materials and methods

Participants

Thirty-eight individuals, 19 in their first episode schizophrenia (FESZ; 4 females), and 19 healthy controls (HC; 9 females), were recruited as part of the Boston Center for Intervention Development and Applied Research (CIDAR) study (www.bostoncidar.org), “Vulnerability to Progression in Schizophrenia”. HC were recruited from the general community via Internet advertisements. FESZ were recruited from local hospital and outpatient clinics affiliated with Harvard Medical School, or through referrals from clinicians. The study was approved by the local IRB committees at Harvard Medical School, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Veteran Affairs Boston Healthcare System (Brockton campus). All study participants gave written informed consent and received payment for participation.

HC were drawn from the same geographic base as the FESZ group with comparable age, gender, race and ethnicity, handedness, and parental socioeconomic status (PSES). No HC met criteria for any current major DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, or any history of psychosis, Major Depression (recurrent), Bipolar disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or developmental disorders. Controls were also excluded for any history of psychiatric hospitalizations, prodromal symptoms, schizotypal or other Cluster A personality disorders, first degree relatives with psychosis, or any current or past use of antipsychotics (other past psychotropic medication use was acceptable, but the subjects must have been off medicine for at least 6 months before participating in the study, except for as needed medications like sleeping medications or anxiolytic agents, such as beta-blockers for performance anxiety, tremors, etc.). Exclusion criteria for all participants were: sensory-motor handicaps, neurological disorders, medical illnesses that significantly impair neurocognitive function, diagnosis of mental retardation, education less than 5th grade if under 18 or less than 9th grade if 18 or above, not fluent in English, DSM-IV-TR substance abuse in the past month, DSM-IV-TR substance dependence, excluding nicotine, in the past 3 months, current suicidality, no history of ECT within the past five years for patients and no history of ECT ever for controls, or study participation by another family member. In addition, HC subjects, recruited from the general community, were screened to exclude individuals with Axis I disorder in themselves or in a first-degree relative.

Clinical diagnoses were based on interviews with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID), Research Version (First et al., 2002) or the Kid-SCID (Hien et al., 1994) for subjects <18, as well as information from available medical records. All FESZ participants met DSM-IV-TR criteria for either schizophrenia (N=16), or schizoaffective disorder (N=3). FESZ clinical symptoms were rated using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Andreasen, 1984) and Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen, 1984). For FESZ participants, the average time between first hospitalization and the baseline MRI scanning session was 0.7 ± 0.7 years (range 0.0–2.0 years).

All participants were evaluated using the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (Jones et al., 1995) (GAF). Parental socioeconomic status (PSES) was assessed using the Hollingshead four-factor index (Hollingshead, 1975). Premorbid intellectual abilities were estimated using the Reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test-4 (WRAT-4) (Wilkinson and Robertson, 2006) and current intellect was estimated using the Vocabulary and Block Design subtests of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (Wechsler, 1999). Fifteen of 19 FESZ were medicated at the time of testing. All subjects but one were medicated with second generation antipsychotics. Medication dosage was estimated using chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalents (see Table 1) (For further subjects’ information see (Del Re et al., 2014; del Re et al., 2015). All demographic and clinical data are summarized in Table 1.

Table I.

Socio-demographic and Clinical Information

| HC (N=19) | FESZ (N=19) | F | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 22.3 (3.8) | 22.3 (4.0) | 0.005 | 0.95 |

| Gender (male/female) | 10/9 | 15/4 | --- | 0.2 |

| Pre-morbid IQ (WRAT reading) | 108.0 (20.6) | 113 (13.9) | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| Current IQ (WASI) | 117.2 (15.0) | 109.7 (12.4) | 2.72 | 0.11 |

| Parental SES | 1.95 (0.9) | 2.2 (1.2) | 0.38 | 0.54 |

| Interval MRI-First Hospitalization (years) | --- | 0.7 (0.7) | --- | N.A. |

| CPZ Baseline | --- | 228.3 (196.5) | --- | N.A. |

| CPZ Follow-up | --- | 318.3 (371) | --- | N.A. |

| SAPS Baseline | --- | 18.4 (17.2) | --- | N.A. |

| SAPS Follow-up | --- | 9.6 (12.5) | --- | N.A. |

| SANS Baseline | --- | 28.7 (12.2) | --- | N.A. |

| SANS Follow-up | --- | 20.5 (17.8) | --- | N.A. |

| GAF Baseline | 82.1 (9.5) | 52.1 (9.0) | 97.4 | <0.01 |

| GAF Follow-up | 82.1 (10.9) | 63.3 (13.5) | 21.0 | <0.01 |

Values are mean (SD); HC, Healthy controls; FESZ, First episode schizophrenia patients; CPZ, Chlorpromazine; All antipsychotics but one were second generation; CPZ were calculated for FESZ on antipsychotic medication (14/19); SES, Socioeconomic Status; N.A., not applicable. CPZ equivalents were calculated according to Stoll (2009) and Woods (2003).

MRI Image Acquisition

MR images were acquired on a 3-Tesla whole body MRI Echospeed system General Electric scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee). An eight-channel coil was used in order to perform parallel imaging using ASSET (Array Spatial Sensitivity Encoding techniques, GE) with a SENSE acceleration factor of 2. The structural MRI acquisition protocol included the following pulse sequence and parameters: contiguous inversion-prepared spoiled gradient-recalled acquisition (fastSPGR), TR=7.4ms, TE=3ms, TI=600 ms, 10 degree flip angle, 25.6 × 25.6 field of view, and matrix=256×256. The voxel dimensions were 1×1×1 mm.

MRI Image Processing

Each MRI scan was visually inspected for movement artifacts. Images were realigned to the anterior commissure- posterior commissure (AC-PC) line and to the sagittal sulcus to correct for head tilt. Multi atlas brain segmentation (del Re et al., in press, J. Neuroimaging, 2015) was employed to automatically mask the brain. FreeSurfer 5.3 (Fischl et al., 2002) was employed to segment the scans and extract corpus callosum segmentations and ventricle sizes (Figures 1 and 2).

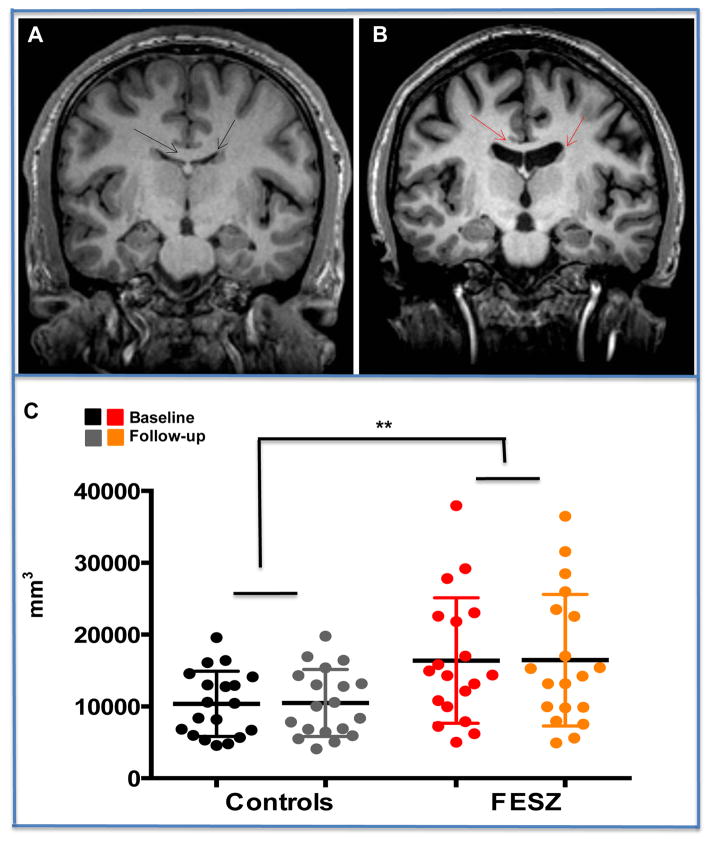

Figure 1.

Upper Panel (A) Coronal T1-weighted MRI slice of a representative control subject and (B) a representative FESZ patient at Baseline. Arrows indicate lateral ventricles and the corpus callosum. Lower Panel. (C) Mean and S.D. of bilateral lateral ventricles in controls at baseline and at follow-up (black and gray circles, respectively); and in FESZ at baseline and at follow-up (red and orange circles, respectively). Volume of bilateral lateral ventricles of first episode schizophrenia subjects (FESZ) was significantly increased compared to volume of bilateral lateral ventricles in controls. The increase remained stable at follow-up.

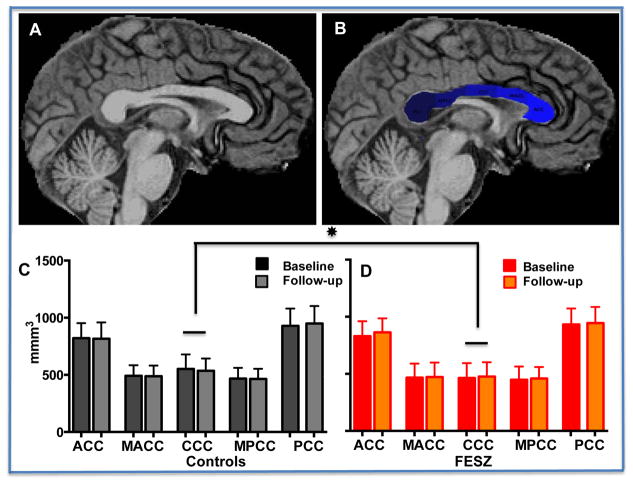

Figure 2.

Upper panel (A) Sagittal view of a representative T1-weighted MRI of control subject and (B) same view showing FreeSurfer v. 5.3 segmentation of the corpus callosum. Lower panel. (C) Volumes of corpus callosum sub-regions in controls at baseline (black columns) and follow-up (gray columns); (D) Volumes of corpus callosum sub-regions in FESZ at baseline (red columns) and follow-up (orange columns). In first episode schizophrenia subjects (FESZ) the central corpus callosum volume was significantly decreased with comparison to the central corpus callosum volume measured in controls. The decrease was stable at follow-up. Key for Abbreviations: ACC, anterior part of the corpus callosum; MACC, middle anterior part; CCC, central corpus callosum; MPCC, mid posterior corpus callosum; PCC, posterior corpus callosum.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS v. 22, the exception being effect sizes, which were calculated with G*Power 3.1, 2009 (Faul et al., 2007).

MRI volume analyses

Repeated measures two-factors ANCOVA or univariate ANCOVA (for the third ventricle) were used with Group and Gender as a between-subjects factors to determine group differences in volumes at baseline. The lateral ventricle analysis included Hemisphere as a within-subjects factor (right versus left), and the corpus callosum analysis included the five segmentations of the corpus callosum.

For all of these analyses, intracranial content volume was used as a covariate.

In order to determine volumetric changes between baseline and follow-up, percent change in volume between follow-up and baseline was calculated for each ROI according to the formula [(Value Follow-up -Value Baseline/Value Baseline)*100]. The percent changes of the volumes, now standardized, were all analyzed in one repeated measures ANCOVA (including eight ROIs as follows: right and left lateral ventricles, third ventricle, and the five segments of the corpus callosum). For this analysis the percent change in intracranial volume was used as a covariate.

Please note that separate right and left LV percent volume changes were used in this analysis to determine whether the left and the right ventricles might have different percent volume changes between baseline and follow-up. Gender was included to determine whether different percent changes between baseline and follow-up would be present.

Correlation analyses

Correlations among MRI volumetric measures, and correlations between MRI volumetric measures and clinical/functional measures were computed using Spearman’s rho. We kept the number of correlations to a minimum in order to control for multiple correlations. For the LVs, the sum of right and left lateral ventricles, referred to as bilateral lateral ventricle, was employed in the correlation analyses as no main effect or significant interaction of Hemisphere had been found. Bonferroni correction was applied to all correlations as detailed below. For correlations between volumes, Bonferroni corrected threshold p value was set as follows: 0.05/3 correlations=0.017 (bilateral LV, third ventricle, and central CC). For the clinical/functional data, the Bonferroni corrected threshold p value was calculated as follows: 0.05/12 correlations=0.0042 and the variables were: Total SAPS, total SANS, GAF, CPZ equivalents and three regions, LV, central CC and third ventricle. A Chi-square test was used to compare categorical data.

Results

Subject group characteristics

FESZ and control groups did not differ in age, years of education, premorbid IQ, or current IQ, as summarized in Table 1. Significant group differences were, however, found for the GAF (Table 1).

Volumetric analyses at baseline

Left and right lateral ventricles

Findings showed a main effect of Group [F(1,33)=9.7; p=0.004] (Figure 1), with no main effect of Hemisphere [F(1,33)=3.55; p=0.07) and no significant Group X Hemisphere interaction [F(1,33)=3.96; p=0.06].

There was also no main effect of Gender [F(1,33)=0.174; p=0.69] and no significant interaction of Group by Gender [F(1,33)=0.242; p=0.63]. In addition, there were no significant three-way interactions found.

The lack of hemisphere effect on LVs volumes prompted us to create one ROI comprised of the sum of the right and left LVs volumes, hereafter referred to as bilateral LVs, to be used in the correlational analyses. To confirm the appropriateness of this approach, a univariate ANCOVA of bilateral LVs was run. Results confirmed a significant main effect of Group [F(1,33)=9.6; p=0.004] and a lack of other significant interactions.

Third Ventricle

Univariate ANCOVA indicated a significant main effect of Group [F(1,33)=4.11; p=0.05), with no significant main effect of Gender [F(1,33)=0.16; p=0.7] or other significant interactions.

Segmentation of the corpus callosum

Repeated measures ANCOVA of the CC (Figure 2) did not show a main effect of Group [F(1,33)=0.011; p=0.9], or a main effect of Gender [F(1,33)=0.17; p=0.68]. No other statistically significant interactions were observed except for a significant interaction of ROIs X Group [F(4,132)=3.7; p=0.015].

Post-hoc analysis of the ROIs demonstrated a statistically significant main effect of Group for the central CC [F(1,35)=5.6; p=0.024].

Volumetric Analyses at Follow-up: Percent Changes over Baseline

Percent Volume Changes were not different for the eight ROIs entered into the analysis [F(7,238)=0.92; p=0.37]. In addition, no interaction for Percent Volume Changes X Group was found [F(7,238)=1.2; p=0.3]. There was also no significant main effect for Group [F(1,33)=0.24; p=0.63] or for Gender [F(1,33)=1.1; p=0.31]. Finally, there were no significant interactions for Gender X Group [F(1,33)=0.6; p=0.44], and no other statistically significant two-ways or three-ways interactions.

Correlations between volumes

To determine the relationship between LV, third ventricle and central CC, Spearman’s rho correlation analyses were carried out in both controls and FESZ at baseline. In controls, volumes of the bilateral LV positively correlated with volume of the third ventricle (rho=0.672, p<0.05). In controls, there were no significant correlations between the volumes of the central corpus callosum and volume of the ventricles.

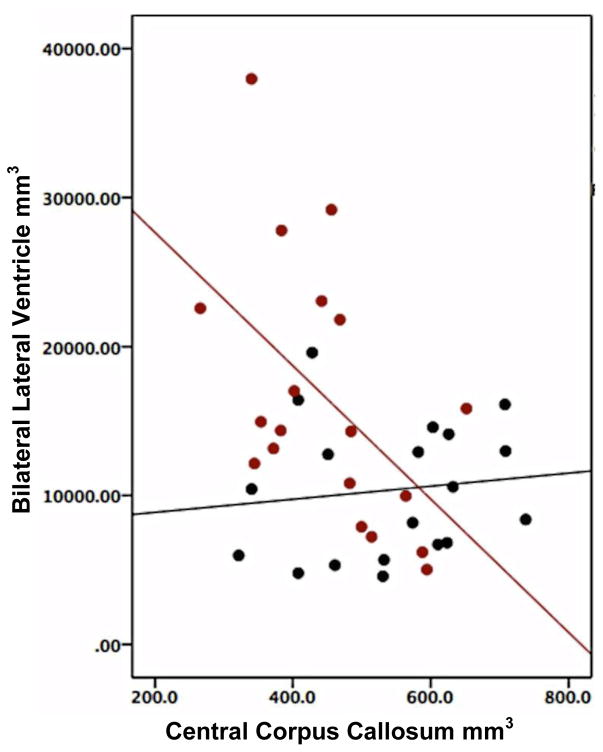

In FESZ, a positive, statistically significant correlation was found between the volumes of bilateral LVs and third ventricle (rho=0.62, p<0.05). At baseline, a statistically significant inverse correlation was also found between the volume of the bilateral LV and that of the central CC (rho=−0.59, p<0.05) (Figure 3), and between the volume of the third ventricle and the volume of the central CC (rho=−0.681, p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Correlation between volumes of bilateral lateral ventricle and central corpus callosum in controls and FESZ. Volume of the Bilateral lateral ventricle in FESZ is highly and inversely correlated with volume of the central corpus callosum (red dots and red least squares fit). There is no correlation between volume of the bilateral lateral ventricle and central corpus callosum in controls (black dots and black least square fit).

Correlation between volumes and clinical and functional scales in FESZ

No significant correlations were found between volumes of the central CC, the bilateral LV or the third ventricle with SAPS and SANS total scores or GAF. There were no significant correlations between volumes and CPZ equivalents.

Correlation between baseline/follow-up volume changes and baseline/follow-up clinical and functional scales changes

Correlations between percent changes of clinical scales between baseline and follow-up with the percent changes in volumes for each region studied were also investigated. In FESZ, an inverse correlation was found between the percent volume change between baseline and follow-up of bilateral LV and the percent change in GAF (rho=−0.65, p<0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Percent volume change was calculated according to the formula [(Value Follow-up −Value Baseline/Value Baseline)*100]. Percent GAF change was calculated with same formula.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of both the ventricular system and CC in the same investigation in first episode SZ, a surprising fact considering that both LVs and CC abnormalities are hallmark features of the disease and intimately associated. Abnormalities of both CC and LVs appear together in neurodevelopmental syndromes such as agenesis, or partial agenesis of the CC, developmental disorders, which are themselves highly heritable (Bergen and Petryshen, 2012).

Thus, the goal of the present investigation was to explore the relationship between the corpus callosum and third and lateral ventricles’ volumetric changes in first episode schizophrenia patients as the disease progressed. We hypothesized the existence of correlations between the volumes of the ventricular system and that of the corpus callosum in an early schizophrenia disease state (Alexander-Bloch et al., 2013; Pfefferbaum et al., 2000). The first episode schizophrenia subjects were initially assessed about 0.7 years after first hospitalization, and again longitudinally at 1.2 years after baseline assessment, providing data on early disease and early progression beyond the acute psychotic outbreak. With the aim of standardizing the partitioning of the corpus callosum, we adopted FreeSurfer v5.3 automatic segmentation as this has been successfully used in several studies (Johnson et al., 2013) (Francis et al., 2011) (Salat et al., 2005) and very closely approximate other accepted corpus callosum segmentations (Hofer and Frahm, 2006) (Witelson, 1989).

At baseline, the volumes of the lateral and third ventricles were found to be significantly increased in FESZ compared to healthy controls. At follow-up, the initial volume increase found in the ventricles at baseline remained stable without change, i.e. there was no significant main effect of Time and no significant interaction of Group by Time. In the same population at baseline, there was a significantly smaller volume of the central part of the corpus callosum in FESZ with comparison to healthy controls. The decreased CC volume in FESZ compared to controls was also present at follow-up without significant effects of Time or significant interaction of Time by Group.

The relationship between ventricular system and corpus callosum was explored by employing correlation analysis (Narr et al., 2002). Strong positive correlations were found between volumes of the lateral and third ventricles in both controls and FESZ. A strong inverse correlation between volumes of the lateral ventricles and central corpus callosum, and an inverse correlation between volumes of the third ventricle and central corpus callosum were also found in FESZ. This inverse correlation between ventricles and CC was not present in controls.

Volume increases of the LVs are characteristic of schizophrenia (Brent et al., 2013; Kempton et al., 2010; Shenton et al., 2001) together with schizophrenia-associated changes of the corpus callosum (Arnone et al., 2008); Woodruff et al., 1995). Nonetheless, research on the relation between abnormalities of the two structures in schizophrenia is very scant.

In chronic schizophrenia patients, morphology of the corpus callosum has been found to be related to structural differences in surrounding neuroanatomical regions, including volume of the lateral ventricles (Narr et al., 2000).

Using a classic twin study design, only a few studies have focused on the genetic relationship between the corpus callosum and lateral ventricle volume. An investigation of a large sample of older monozygotic and dizygotic healthy male twins (Pfefferbaum et al., 2004; Pfefferbaum et al., 2000) has demonstrated that strong genetic (rg =.68) and environmental (re = .58) correlations explain the relationship between corpus callosum height and lateral ventricle size (Pfefferbaum et al., 2000). In a younger population of mono- and dizygotic schizophrenia twins, no difference in callosal area was found between affected and unaffected twins, nonetheless callosal displacement and curvature were found to be related to lateral and third ventricles enlargement (Narr et al., 2002). Interestingly, in this latter study, displacement of the dorsal surface of the CC was present in affected dizygotic twin compared to healthy siblings, while the same was found but half of the time in mono-zygotic affected twin with comparison to their healthy siblings, indicating that genetic influences rather than environmental ones contribute to callosal displacement in affected and un-affected monozygotic twins (Narr et al., 2002).

More recently, a schizophrenia-associated single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the microRNA 137 (MIR137) -- one of the most significantly schizophrenia-associated SNPs from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, 2014) -- has been shown to associate with enlarged lateral ventricles and decreased white matter integrity. The two measures were correlated in schizophrenia patients (Lett et al., 2013). MIR137 regulates adult neural stem cell maturation and migration in the subventricular zone in close proximity to the lateral ventricles (Wright et al. 2015). It also regulates gliogenesis, essential to white matter development (Silber et al., 2008). Of note, in a completely independent study from that of Lett and colleagues (2013), MIR137 has also been associated with worse functioning and severe cognitive deficits in schizophrenia (Green et al., 2013).

Abnormal volumetric enlargement of the ventricular system has been shown to index and possibly predict what is defined as poor outcome Kraepelinian schizophrenia, characterized by severe lack of self-care, severe disturbance in socio-sexual functioning and severe negative symptoms (Mitelman and Buchsbaum, 2007) (Cahn et al., 2006; DeLisi et al., 1992). Within FESZ it has been shown that the greater the bilateral lateral ventricle progressive enlargement, the greater the change in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale withdrawal-retardation score (Nakamura et al., 2007). In a longitudinal MRI and clinical measures study with follow-up at five years, patients with schizophrenia were sub-grouped into poor GAF score (N=47) and good GAF score (N=47) at the 5 year follow-up point, where GAF was the outcome variable of the longitudinal assessment. The poor outcome group, defined as poor GAF score, showed a larger increase in lateral ventricle volume (van Haren et al., 2008).

The data presented here support those findings of the ventricular system as an index of functioning. In particular we demonstrate that changes in ventricular volumes between baseline and reassessment denote changes in global functioning measures.

With respect to the corpus callosum, volume of this tract has most often been found to correlate with positive symptoms (Nasrallah et al., 1985; Rotarska-Jagiela et al., 2008; Serpa et al., 2012; Whitford et al., 2010), however, correlations have not necessarily been found with the body of the corpus callosum, the portion of the corpus callosum that was found to be abnormal in this investigation.

All in all, we speculate that these converging data may suggest that in schizophrenia shared relationships between corpus callosum and ventricles might be related by specific schizophrenia-associated mechanisms, possibly by gene polymorphisms such as, for example, the schizophrenia-associated variant of the MIR137 gene (Lett et al., 2013; Narr et al., 2000) (Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study, 2011).

No progression of ventricular or corpus callosum volume abnormalities was found at one year follow-up in this investigation, perhaps because of the relatively short test-retest interval. In fact, comprehensive meta-analyses of longitudinal studies have unequivocally shown progressive enlargement of lateral ventricles in schizophrenia but progression was evaluated in studies where follow-up reassessment was considered in a range of one up to many years after baseline evaluation (Fusar-Poli et al., 2013; Kempton et al., 2010; van Haren et al., 2008). The possibility that medication might slow the rate of ventricular enlargement in our particular sample of schizophrenia subjects was explored, but no correlations were found between volumes of the ventricles and chlorpromazine equivalents at baseline or follow-up. Indeed, ventricular enlargement in schizophrenia has been shown to be mostly independent from cumulative anti-psychotic treatment (Fusar-Poli et al., 2013). With respect to the corpus callosum size, progression has been demonstrated in chronic schizophrenia but re-assessment was carried out at four years after baseline measurement (Mitelman et al., 2009). We hypothesize that the rate of progression of ventricle volume enlargement and corpus callosum volume is slower in the phase of early, stable schizophrenia, and too subtle to be detected at one year follow-up. Furthermore, the complex interplay between schizophrenia, volumetric changes, age at MRI assessment and time interval to reassessment makes it difficult to compare longitudinal studies.

There are limitations to the research data presented here. The sample size is relatively small, and almost all of the schizophrenia subjects were medicated. However, no medication effects could be demonstrated through correlation analyses between chlorpromazine equivalents and volumetric measures of the ventricles or the corpus callosum. Nonetheless, future studies in larger schizophrenia samples and in clinical high-risk subjects will be important for validating the present results.

In summary, we have demonstrated stable volumetric enlargement of the ventricular system that correlates inversely with stable volumetric decreases of the central corpus callosum in first episode schizophrenia patients assessed ~0.7 years after first hospitalization. Our data support a model that implicates schizophrenia specific mechanisms in shaping the relationship between the ventricle system and the corpus callosum. We hypothesize that the relationship might be due to schizophrenia-associated common genetic mechanisms. As the ventricular system is easily identified and easily measurable on MRI, we propose that monitoring changes in ventricle volumetric features might help understand global functioning in schizophrenia patients. Thus, it will be important to further investigate the relationship between ventricles and corpus callosum, diffusion tensor measures related to the corpus callosum and especially the central portion of it, environmental insults, and their genetic and clinical correlates in a very large sample of schizophrenia subjects.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

This study was conducted in part by the P50 MH080272 Boston Center for Intervention Development and Applied Research (Boston CIDAR; RWM PI, MES, LJS, RI-M-G, JG, TLP), entitled: “Longitudinal Assessment and Monitoring of Clinical Status and Brain Function in Adolescents and Adults.” This work was also supported in part by R01 MH40799 (RWM) and R01MH092380 (TLP) from National Institutes of Health, by the Commonwealth Research Center (SCDMH82101008006, LJS), and by a Clinical Translational Science Award UL1RR025758 to Harvard University and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center from the National Center for Research Resources (LJS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We thank all subjects who participated in the study. We also thank the clinical, research assistant, and data management staff from the Boston CIDAR study, including Ann Cousins, PhD, APRN, Michelle Friedman-Yakoobian, PhD, Anthony J. Giuliano, PhD, Matcheri Keshavan, MD, Janine Rodenhiser-Hill, PhD, Kristen A. Woodberry, MSW, PhD, Andréa Gnong-Granato,MSW, Lauren Gibson, EdM, Sarah Hornbach, BA, Julia Schutt,BA, Kristy Klein, PhD, Maria Hiraldo, PhD, Grace Francis, PhD, Corin Pilo, LMHC, Rachael Serur, BS, Reka Szent-Imry, BA, Shannon Sorenson, BA, Grace Min, EdM, Alison Thomas, BA, Chelsea Wakeham, BA, Caitlin Bryant, BS, and Molly Franz, BA. Finally, we are grateful for the hard work of many research volunteers, including Zach Feder, Elizabeth Piazza, Julia Reading, Devin Donohoe, Sylvia Khromina, Alexandra Oldershaw, and Olivia Schanz.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

All authors declare that they do not have conflicts of interest.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, and the applicable revisions at the time of the investigation. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Contributors

E.C. del Re designed this study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; J. Konishi helped with data analysis; S. Bouix helped with MRI tools and edited the manuscript; G. Blokland, O. Pasternak, J. Goldstein, M. Kubicki, Y. Hirayasu and Margaret Niznikiewicz edited the manuscript; R. Mesholam-Gately and L. Seidman recruited the subjects, collected clinical data, edited the manuscript and contributed funding (LJS); T. Petryshen edited the manuscript and contributed funding for this project; M. Shenton and R. McCarley contributed funding for this research project and contributed to manuscript writing and data analysis.

References

- Alexander-Bloch AF, Vertes PE, Stidd R, Lalonde F, Clasen L, Rapoport J, et al. The anatomical distance of functional connections predicts brain network topology in health and schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(1):127–138. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms. Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D, McIntosh AM, Tan GM, Ebmeier KP. Meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies of the corpus callosum in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1–3):124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balevich EC, Haznedar MM, Wang E, Newmark RE, Bloom R, Schneiderman JS, et al. Corpus callosum size and diffusion tensor anisotropy in adolescents and adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2015;231(3):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen SE, Petryshen TL. Genome-wide association studies of schizophrenia: does bigger lead to better results? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):76–82. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835035dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokland GA, de Zubicaray GI, McMahon KL, Wright MJ. Genetic and environmental influences on neuroimaging phenotypes: a meta-analytical perspective on twin imaging studies. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2012;15(3):351–371. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent BK, Thermenos HW, Keshavan MS, Seidman LJ. Gray matter alterations in schizophrenia high-risk youth and early-onset schizophrenia: a review of structural MRI findings. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013;22(4):689–714. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahn W, van Haren NE, Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Caspers E, Laponder DA, et al. Brain volume changes in the first year of illness and 5-year outcome of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:381–382. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.015701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Re EC, Bergen SE, Mesholam-Gately RI, Niznikiewicz MA, Goldstein JM, Woo TU, et al. Analysis of schizophrenia-related genes and electrophysiological measures reveals ZNF804A association with amplitude of P300b elicited by novel sounds. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e346. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Re EC, Spencer KM, Oribe N, Mesholam-Gately RI, Goldstein J, Shenton ME, et al. Clinical high risk and first episode schizophrenia: auditory event-related potentials. Psychiatry Res. 2015;231(2):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Re EC, Gao Y, Eckbo R, Petryshen TL, Blokland GAM, Seidman LJ, Konishi J, Goldstein JM, McCarley RW, Shenton ME, Bouix S. A new MRI masking technique based on multi-atlas brain segmentation in controls and schizophrenia: a rapid and Viable alternative to manual masking. J Neuroimaging. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jon.12313. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi LE, Hoff AL, Kushner M, Calev A, Stritzke P. Left ventricular enlargement associated with diagnostic outcome of schizophreniform disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;32(2):199–201. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90025-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downhill JE, Jr, Buchsbaum MS, Wei T, Spiegel-Cohen J, Hazlett EA, Haznedar MM, et al. Shape and size of the corpus callosum in schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder. Schizophr Res. 2000;42(3):193–208. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Pincus HA. The DSM-IV Text Revision: rationale and potential impact on clinical practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(3):288–292. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons JM, Kubicki M, Shenton E. Review of functional and anatomical brain connectivity findings in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(2):172–187. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835d9e6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis AN, Bhojraj TS, Prasad KM, Kulkarni S, Montrose DM, Eack SM, et al. Abnormalities of the corpus callosum in non-psychotic high-risk offspring of schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res. 2011;191(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Smieskova R, Kempton MJ, Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Borgwardt S. Progressive brain changes in schizophrenia related to antipsychotic treatment? A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(8):1680–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goghari VM, Lang DJ, Flynn SW, Mackay AL, Honer WG. Smaller corpus callosum subregions containing motor fibers in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;73(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, Cairns MJ, Wu J, Dragovic M, Jablensky A, Tooney PA, et al. Genome-wide supported variant MIR137 and severe negative symptoms predict membership of an impaired cognitive subtype of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(7):774–780. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien D, Matzner FJ, First MB, Sptizer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-child edition (version 1.0) New York: Columbia University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer S, Frahm J. Topography of the human corpus callosum revisited--comprehensive fiber tractography using diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2006;32(3):989–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Two-factor index of social position. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Mandl RC, Cahn W, Collins DL, Evans AC, et al. Focal white matter density changes in schizophrenia: reduced inter-hemispheric connectivity. Neuroimage. 2004;21(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Schizophrenia C. Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O’Donovan MC, et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460(7256):748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Greenstein D, Clasen L, Miller R, Lalonde F, Rapoport J, et al. Absence of anatomic corpus callosal abnormalities in childhood-onset schizophrenia patients and healthy siblings. Psychiatry Res. 2013;211(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone EC, Crow TJ, Frith CD, Husband J, Kreel L. Cerebral ventricular size and cognitive impairment in chronic schizophrenia. Lancet. 1976;2(7992):924–926. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90890-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SH, Thornicroft G, Coffey M, Dunn G. A brief mental health outcome scale-reliability and validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(5):654–659. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.5.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempton MJ, Stahl D, Williams SC, DeLisi LE. Progressive lateral ventricular enlargement in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1–3):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Diwadkar VA, Harenski K, Rosenberg DR, Sweeney JA, Pettegrew JW. Abnormalities of the corpus callosum in first episode, treatment naive schizophrenia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72(6):757–760. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen WS, Fennema-Notestine C, Eyler LT, Panizzon MS, Chen CH, Franz CE, et al. Genetics of brain structure: contributions from the Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162B(7):751–761. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki M, Shenton ME. Editorial to special issue on “white matter pathology”. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazo DL. Fundamentals of sectional anatomy: an imaging approach. 1st. Stamford: Cengage Learning; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lencz T, Smith CW, McLaughlin D, Auther A, Nakayama E, Hovey L, et al. Generalized and specific neurocognitive deficits in prodromal schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(9):863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lett TA, Chakravarty MM, Felsky D, Brandl EJ, Tiwari AK, Goncalves VF, et al. The genome-wide supported microRNA-137 variant predicts phenotypic heterogeneity within schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(4):443–450. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman SA, Buchsbaum MS. Very poor outcome schizophrenia: clinical and neuroimaging aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):345–357. doi: 10.1080/09540260701486563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman SA, Nikiforova YK, Canfield EL, Hazlett EA, Brickman AM, Shihabuddin L, et al. A longitudinal study of the corpus callosum in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;114(1–3):144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Salisbury DF, Hirayasu Y, Bouix S, Pohl KM, Yoshida T, et al. Neocortical gray matter volume in first-episode schizophrenia and first-episode affective psychosis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(7):773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narr KL, Thompson PM, Sharma T, Moussai J, Cannestra AF, Toga AW. Mapping morphology of the corpus callosum in schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10(1):40–49. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narr KL, van Erp TG, Cannon TD, Woods RP, Thompson PM, Jang S, et al. A twin study of genetic contributions to hippocampal morphology in schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;11(1):83–95. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah HA, Jacoby CG, Chapman S, McCalley-Whitters M. Third ventricular enlargement on CT scans in schizophrenia: association with cerebellar atrophy. Biol Psychiatry. 1985;20(4):443–450. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(85)90046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Johnson JK, McKinley M, Loewy R, O’Brien M, et al. Neurocognitive performance and functional disability in the psychosis prodrome. Schizophr Res. 2006;84(1):100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, Gorham DR, Shawver JR. Basic dimensions of change in the symptomatology of chronic schizophrenics. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1961;63:597–602. doi: 10.1037/h0039893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Westin CF, Bouix S, Seidman LJ, Goldstein JM, Woo TU, et al. Excessive extracellular volume reveals a neurodegenerative pattern in schizophrenia onset. J Neurosci. 2012;32(48):17365–17372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2904-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul LK. Developmental malformation of the corpus callosum: a review of typical callosal development and examples of developmental disorders with callosal involvement. J Neurodev Disord. 2011;3(1):3–27. doi: 10.1007/s11689-010-9059-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Carmelli D. Morphological changes in aging brain structures are differentially affected by time-linked environmental influences despite strong genetic stability. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(2):175–183. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Swan GE, Carmelli D. Brain structure in men remains highly heritable in the seventh and eighth decades of life. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotarska-Jagiela A, Schonmeyer R, Oertel V, Haenschel C, Vogeley K, Linden DE. The corpus callosum in schizophrenia-volume and connectivity changes affect specific regions. Neuroimage. 2008;39(4):1522–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Tuch DS, Greve DN, van der Kouwe AJ, Hevelone ND, Zaleta AK, et al. Age-related alterations in white matter microstructure measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(8):1215–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scamvougeras A, Kigar DL, Jones D, Weinberger DR, Witelson SF. Size of the human corpus callosum is genetically determined: an MRI study in mono and dizygotic twins. Neurosci Lett. 2003;338(2):91–94. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study C. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):969–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpa MH, Schaufelberger MS, Rosa PG, Duran FL, Santos LC, Muray RM, et al. Corpus callosum volumes in recent-onset schizophrenia are correlated to positive symptom severity after 1 year of follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1–3):258–259. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49(1–2):1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silber J, Lim DA, Petritsch C, Persson AI, Maunakea AK, Yu M, et al. miR-124 and miR-137 inhibit proliferation of glioblastoma multiforme cells and induce differentiation of brain tumor stem cells. BMC Med. 2008;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Haren NE, Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Cahn W, Brans R, Carati I, et al. Progressive brain volume loss in schizophrenia over the course of the illness: evidence of maturational abnormalities in early adulthood. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(1):106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatasubramanian G, Jayakumar PN, Reddy VV, Reddy US, Gangadhar BN, Keshavan MS. Corpus callosum deficits in antipsychotic-naive schizophrenia: evidence for neurodevelopmental pathogenesis. Psychiatry Res. 2010;182(2):141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walterfang M, McGuire PK, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Velakoulis D, Wood SJ, et al. White matter volume changes in people who develop psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(3):210–215. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. New York: Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Whitford TJ, Ford JM, Mathalon DH, Kubicki M, Shenton ME. Schizophrenia, myelination, and delayed corollary discharges: a hypothesis. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(3):486–494. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford TJ, Kubicki M, Schneiderman JS, O’Donnell LJ, King R, Alvarado JL, et al. Corpus callosum abnormalities and their association with psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(1):70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide range achievement test. Fourth. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Witelson SF. Hand and sex differences in the isthmus and genu of the human corpus callosum. A postmortem morphological study. Brain. 1989;112(Pt 3):799–835. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.3.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff PW, McManus IC, David AS. Meta-analysis of corpus callosum size in schizophrenia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(4):457–461. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.4.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright C, Calhoun VD, Ehrlich S, Wang L, Turner JA, Bizzozero NI. Meta gene set enrichment analyses link miR-137-regulated pathways with schizophrenia risk. Frontiers in Genetics. 2015;6:147. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]