Abstract

Purpose

To determine the developmental sequence of retinal layers to provide information on where in utero pathologic events might affect retinal development.

Design

Qualitative and quantitative descriptive research.

Methods

A histology collection of human eyes from fetal week (Fwk) 8 to postnatal (P) 10 weeks was analyzed. The length of the nasal and temporal retina was measured along the horizontal meridian in 20 eyes. The location of the inner plexiform layer (IPL) and outer plexiform layer (OPL) was identified at each age, and its length measured.

Results

The human eye retinal length increased from 5.19 mm at Fwk 8 to 20.92 mm at midgestation to 32.88 mm just after birth. The IPL appeared in the presumptive fovea at Fwk 8, reached the eccentricity of the optic nerve by Fwk 12, and was present to both nasal and temporal peripheral edges by Fwk 18–21. By contrast, the OPL developed slowly. A short OPL was first present in the Fwk 11 fovea and did not reach the eccentricity of the optic nerve until midgestation. The OPL reached the retinal edges by Fwk 30. Laminar development of both IPL and OPL occurred before vascular formation.

Conclusions

In human fetal retina, the IPL reached the far peripheral edge of the retina by midgestation and the OPL by late gestation. Only very early in utero events could affect IPL lamination in the central retina, but events occurring after Fwk 20 in the peripheral retina would overlap OPL laminar development in outer retina.

The Primate Retina Develops Over Many Months both in utero and postnatally. Moreover, it has a prominent foveal-to-peripheral gradient such that points on the retina only 2 mm apart may be at strikingly different stages of development.1–4 This marked gradient is not mentioned or not recognized in many older papers, making it difficult to interpret the data presented. Moreover, having accurate timelines of human retinal development at known retinal loci is important for medicolegal issues as well as for knowledge of what regions and layers of the retina may be impacted by in utero events. The widespread use of optical coherence tomography to visualize the prenatal and postnatal human retina has greatly expanded our knowledge of foveal development,5–7 but there is little systematic information on laminar development outside of the fovea in humans. We have analyzed a large collection of human retinas from embryonic to infant, which provides well-preserved material from which such an assessment can be made morphologically.

METHODS

Qualitative and Quantitative Descriptive Analysis was done on 2 groups of human eyes. These were obtained with Human Subjects approval (0447-E/A07). Eyes from fetal week (Fwk) 6–22 were sourced from aborted fetuses obtained after consent by the Human Tissue Laboratory, University of Washington (UW), Seattle. Fetuses containing obvious abnormalities were excluded. Eyes from Fwk 24–40 and postnatal (P) infants were obtained through the support of the UW Neonatal Intensive Care Nursery and the Lions Eye Bank, Seattle. Infants containing obvious abnormalities or congenital conditions that might affect the eye, or eyes that had poor retinal structure, were not used in this study. Fetal age was determined by crown-rump and foot length, and should be taken to be 61 week.

Fetal eyes <Fwk 16 were fixed whole by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer pH 7.4; in older eyes, the cornea and lens were removed before fixation. Eyes were fixed overnight, washed in phosphate buffer, and measured using micrometer calipers for axial length and diameter. For the best morphology, the horizontal meridian containing fovea and optic nerve was embedded in glycol methacrylate, and serially sectioned at 2 μm using glass knives. For frozen sections to be used in other studies, the horizontal meridian was cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in phosphate buffer, and serially frozen sectioned at 12 μm. In both series, every 10th slide was stained with 1% azure II/methylene blue in pH 10.5 borax buffer to identify the fovea, and then additional sections within the fovea were stained for analysis.

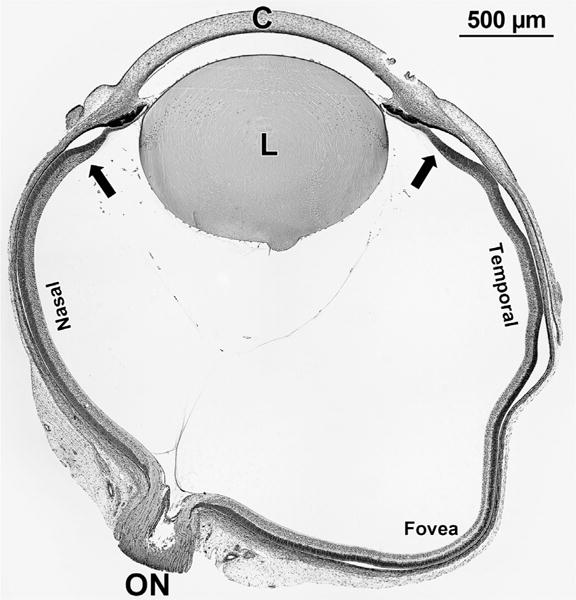

A stained section was selected from 1 well-preserved eye of infants from Fwk 8 to P 1 week; an example is shown in Figure 1. The section contained optic nerve, fovea, and the entire retina, including both nasal and temporal far peripheral edges. The far peripheral edge of the retina is called “edge” in the text and is indicated by arrows in Figure 1. The length of the nasal retina from optic nerve to edge; the nasal retina from optic nerve to foveal center; and the temporal retina from foveal center to edge was measured using a microscope ocular micrometer (Table 1). In selected sections, the inner plexiform layer (IPL) containing bipolar cell and amacrine synapses and outer plexiform layer (OPL) containing cone and rod synapses were identified and the distance from the center of the developing fovea was measured (Table 2). The amount of retina containing IPL and OPL was divided by the total length and expressed as “% coverage” for a given age (Table 2). Selected regions of well-preserved retinas were imaged digitally using a Nikon E1000 wide-field digital microscope. These images were processed in Adobe Photoshop CS5 for size, color balance, sharpness, and contrast.

FIGURE 1.

Section through the horizontal meridian of a fetal week (Fwk) 12 human eye. The cornea (C), lens (L), optic nerve (ON), and fovea are indicated. The peripheral edge of the retina, called “edge” in the text, is marked with arrows.

TABLE 1.

Growth of Human Retina From Fetal Week 8 to Birth

| Individual Eyes

|

Average of Age Groups

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Fetal Week | Nasal ON to Edgea (mm) | Nasal ON to Fovea (mm) | Temporal Fovea to Edgea (mm) | Total Length (mm) | Age Fetal Week | Nasal ON to Edgea (mm) | Nasal ON to Fovea (mm) | Temporal Fovea to Edgea (mm) | Total Length (mm) |

| 8 | 1.9 | 2.98 | 4.88 | ||||||

| 8.4 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 5.5 | 8.2 | 2.1 | 3.09 | 5.19 | ||

| 11.4 | 3.25 | 2.52 | 2.42 | 8.19 | |||||

| 11.4 | 5.05 | 3.35 | 3.24 | 11.64 | 11.4 | 2.95 | 2.66 | 3.40 | 9.02 |

| 12 | 3.70 | 2.75 | 4.45 | 10.9 | |||||

| 13 | 3.75 | 2.72 | 4.17 | 10.64 | 12.5 | 3.73 | 2.74 | 4.31 | 10.78 |

| 14 | 5.75 | 3.52 | 7.48 | 16.45 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | 6.16 | 3.90 | 7.17 | 17.23 | |||||

| 15 | 6.01 | 3.24 | 6.70 | 15.95 | 15 | 5.97 | 3.55 | 7.17 | 16.64 |

| 18 | 7.18 | 3.35 | 8.95 | 19.48 | |||||

| 18 | 8.13 | 4.18 | 9.06 | 21.37 | 18 | 7.66 | 3.77 | 9.01 | 20.43 |

| 21 | 8.66 | 4.36 | 8.25 | 21.27 | |||||

| 21 | 8.26 | 4.2 | 8.1 | 20.56 | 21 | 8.46 | 4.28 | 8.18 | 20.92 |

| 25 | 11.7 | 4.13 | 11.87 | 27.7 | |||||

| 26 | 12.23 | 3.17 | 13.41 | 28.81 | 25.5 | 11.97 | 3.65 | 12.64 | 28.26 |

| 35 | 13.36 | 3.16 | 14.07 | 30.59 | |||||

| 37 | 12.54 | 3.16 | 14.74 | 30.44 | 36 | 12.95 | 3.16 | 14.41 | 30.52 |

| 40 | 14.28 | 3.10 | 15.94 | 33.32 | |||||

| 41 | 13.8 | 2.93 | 15.71 | 32.24 | 40.5 | 14.04 | 3.02 | 15.83 | 32.88 |

ON = optic nerve.

Edge refers to far peripheral retinal edge (Figure 1, arrows).

TABLE 2.

Human Prenatal Retinal Development of Inner Plexiform and Outer Plexiform Layers

| Age Fetal Week | Total Length Retina (mm) | Inner Plexiform Layer

|

Outer Plexiform Layer

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal ON to Edgea (mm) | Nasal ON to Fovea (mm) | Temporal Fovea to Edgea (mm) | Length IPL (mm) | % Coverageb IPL | Nasal ON to Edgea (mm) | Nasal ON to Fovea (mm) | Temporal Fovea to Edgea (mm) | Length OPL (mm) | % Coverageb OPL | ||

| 8 | 4.88 | – | 1.24 | 0.5 | 1.74 | 36 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8.4 | 5.5 | – | 1.11 | 0.4 | 1.51 | 28 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11.4 | 8.19 | 0.65 | 2.3 | 0.55 | 3.5 | 43 | – | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 9 |

| 12 | 10.64 | 0.47 | 2.25 | 0.91 | 3.63 | 34 | – | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 7 |

| 13 | 10.9 | 1.65 | 2.75 | 3.11 | 7.51 | 69 | – | 1.55 | 1.26 | 2.81 | 26 |

| 15 | 17.23 | 4.91 | 3.9 | 6.52 | 15.33 | 89 | – | 2.4 | 2.89 | 5.29 | 31 |

| 15 | 15.95 | 5.51 | 3.24 | 5.92 | 14.67 | 92 | 5.97 | 1.95 | 1.97 | 9.88 | 62 |

| 18 | 19.48 | 7.18 | 3.35 | 7.75 | 18.28 | 94 | 1.6 | 3.11 | 3.84 | 8.55 | 44 |

| 18 | 21.37 | 6.53 | 4.18 | 8.3 | 19.41 | 89 | 0.35 | 3.27 | 4.09 | 7.71 | 36 |

| 21 | 22.56 | 8.26 | 4.2 | 8.1 | 20.56 | 91 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 3.38 | 6.98 | 31 |

| 25 | 27.7 | 10 | 4.13 | 11.67 | 25.8 | 93 | 11.5 | 4.13 | 12.41 | 27.3 | 98 |

| 26 | 28.81 | 12.23 | 3.17 | 13.41 | 28.11 | 98 | 11.4 | 3.65 | 11.2 | 26.25 | 92 |

IPL = inner plexiform layer; ON=optic nerve; OPL = outer plexiform layer.

Edge refers to the far peripheral retinal edge (Figure 1, arrows).

Coverage refers to the percentage of the total retina that contains each layer.

RESULTS

EYE GROWTH

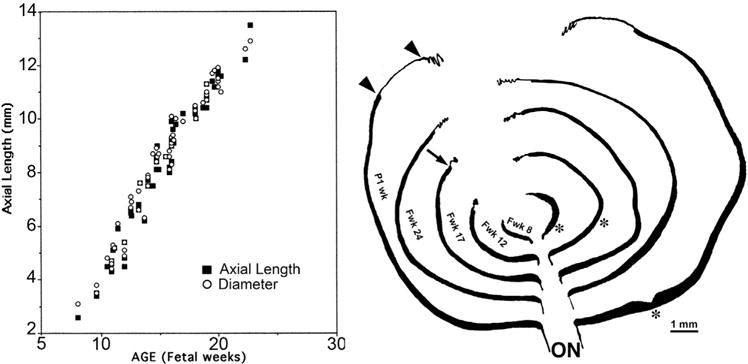

Both axial length and eye diameter almost doubled between Fwk 7 and Fwk 11, doubled again by Fwk 14, and increased another 75% by the end of our measurements at Fwk 27 (Figure 2, Left). Retinal growth along the horizontal meridian from Fwk 8 to P 1 week is depicted schematically in Figure 2, Right. Note the bulge where the fovea is developing in young fetal eyes (Figure 2, Right, asterisks). After midgestation, elongation of the pars plana (Figure 2, Right, double arrows) occurs as part of the eye growth process. Measurements are given in Table 1. At Fwk 8 the human retina averages slightly more than 5 mm long, but by Fwk 11 it has almost doubled in length to 9 mm. At Fwk 11 the retina nasal to the optic nerve is only ~3 mm long while the retina temporal to the optic nerve is twice as long. This is the first age when a fovea can be reliably identified because it is the only retinal region with 5 layers (Figure 4, Left).

FIGURE 2.

Growth of the prenatal human eye. (Left) Gross measurements of axial length and diameter of human eyes from fetal week (Fwk) 7–27. (Right) Schematic drawings showing the elongation of the human horizontal meridian from Fwk 8 (innermost) to postnatal 1 week (outermost). The eyes are aligned on the optic nerve (ON). The asterisks mark the bulge in which the fovea develops. The arrowheads indicate the proximal and distal edge of the nasal pars plana; note its increase in length between Fwk 17 and birth.

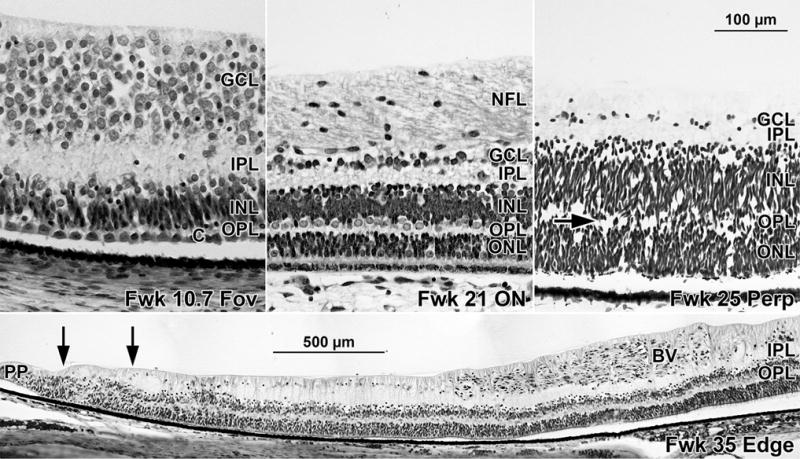

FIGURE 4.

Development of the outer plexiform layer (OPL) in the human retina. (Top right) The fetal week (Fwk) 10.7 fovea is the earliest age that all 5 layers are present. Note the single layer of cones (c) and the thin OPL compared to the thick inner plexiform layer (IPL). (Top middle) Fwk 21 retina temporal to the optic nerve (ON); this region now contains 5 mature layers. (Top right) The developing OPL in the Fwk 25 peripheral retina. The first step involves a gap appearing in the thick outer retina (arrow), dividing it into outer nuclear (ONL) and inner nuclear (INL) layers. Compare the immature OPL with the well-developed IPL at this point. Scale bar in Top right for Top left, middle, and right. (Bottom) Far temporal retina at Fwk 35 with edge of the retina and the pars plana (PP) to the left. The advancing blood vessel front (BV) has not yet reached the retinal edge. All layers are complete close to the edge with an unlaminated region (double arrows) near the PP; this persists until after birth.

After Fwk 11 the nasal retina peripheral to the optic nerve grows steadily, increasing to 6 mm by Fwk 15, 8 mm by Fwk 21, 13 mm by Fwk 26, and 14 mm by birth (Table 1). By contrast, the nasal retina between fovea and optic nerve is never more than 4 mm long and seems to stabilize around 3 mm shortly before birth (Table 1). Up to Fwk 15, the temporal retina from fovea to peripheral edge is longer than from nasal optic nerve to retinal edge (~7 mm vs ~6 mm), and it remains so until late gestation (Figure 2, Right).

MORPHOLOGIC RESULTS

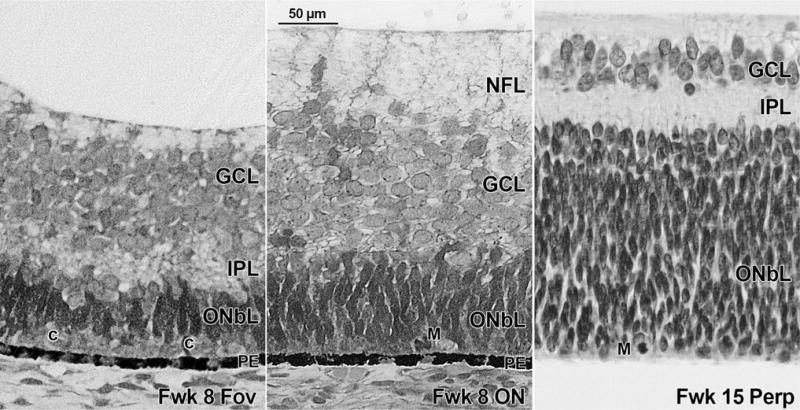

At Fwk 8 the first layers appear in the incipient fovea ~2 mm temporal to the optic nerve (Figure 3, Left). This region is marked by a “bulge” (Figure 1, fovea; Figure 2, Right, asterisks) in eyes before midgestation. A narrow IPL separates the pale ganglion cell layer from the dense thick basophilic outer neuroblastic layer, which later will become the inner nuclear layer and photoreceptor layer. These outer layers are not obvious at this age, although a single layer of large pale cones is present at the outer retina (indicated by “c” in Figure 3, Left). The Fwk 8 IPL covers 1.6 mm of foveal retina and extends farther into nasal than temporal retina, with 32% coverage (Table 2). Most of the remaining retina is divided into an inner layer composed of large pale neurons and an outer layer composed of smaller, densely basophilic neurons with no obvious separating zone (Figure 3, Middle) and many mitotic figures at the outer edge (Figure 3, Middle, right; indicated by “m”). There is a nerve fiber layer (NFL) on the temporal side of the Fwk 8 optic nerve (Figure 3, Middle), suggesting that by this age foveal ganglion cells have extended their axons centrally.

FIGURE 3.

Development of the inner plexiform layer in the human retina. (Left) Fetal week (Fwk) 8 future foveal region showing a narrow inner plexiform layer (IPL) and a thick ganglion cell layer (GCL). Although there are no layers in the outer neuroblastic layer (ONbL), cones (c) can be identified. (Middle) Fwk 8 nasal retina near the optic nerve (ON). Ganglion cell axons (GCL) form a narrow nerve fiber layer (NFL) on the temporal side of the ON. No IPL is present. Mitotic figures (M) are present at the retinal outer surface. (Right) The midperipheral retina at Fwk 15 showing a distinct thick IPL separating the GCL and the thick ONbL. The outer plexiform layer is not yet present, and mitotic figures (M) are numerous at the outer surface. Scale bar in Middle for all.

After Fwk 8 the IPL extends rapidly away from the fovea so that by Fwk 11–12 a distinct IPL is present nasal to the optic nerve. By Fwk 15 it extends 6 mm into both nasal and temporal retina with a coverage of 91% (Figure 3, Right; Table 2). By Fwk 18–21 the IPL is close to the far peripheral edges of both nasal and temporal retina with a coverage of 96%. Thus the IPL covers most of the fetal retina in the 10 weeks between Fwk 8 and Fwk 18.

OPL formation lags well behind the IPL in the young fetal eye. A distinct OPL could not be identified before Fwk 11, although cones are present by Fwk 8 (Figure 3, Left, indicated by “c”). The OPL could only be identified in ~800 μm of the foveal center at Fwk 11, with a single layer of large cones separated by a narrow clear band, the OPL, from the large horizontal cells underneath (Figure 4, Top left). In central retina, cones and rods are beginning to separate from underlying horizontal cells at Fwk 13, but this happens slowly so that at Fwk 18 the OPL still only has a coverage of 44% (Table 2). The OPL is not a fully formed regular layer around the optic nerve until Fwk 18 (Figure 4, Top middle; and Table 2). Thus it is not until midgestation that all layers are present in the 20 degrees of retina central to the optic nerve.

After midgestation the OPL develops more rapidly in peripheral retina. First, a pale gap splits the thick outer neuroblastic layer (Figure 4, Top right, arrow) into photoreceptor and inner nuclear layers, and then the immature OPL widens and becomes free of cells. The OPL is close to both edges by Fwk 30 (96% coverage) and reaches the edge by Fwk 35 (Figure 4, Bottom). Both peripheral retinas have complete lamination before inner retinal vascularization reaches the peripheral edge (Figure 4, Bottom, indicated by “BV”). Because a short length of retina adjacent to the pars plana (Figure 4, Bottom, arrows) remains unlaminated until several months after birth, prenatal coverage never reaches 100%. Data from monkeys indicate that this edge is a mitotically active zone that generates neurons and Müller glia in the far periphery.8

DISCUSSION

Our Data Show that the Human Eye Grows steadily in axial length and diameter until after midgestation, in agreement with earlier studies.9 This indicates that the retina must add new neurons and Müller glia throughout fetal life. The most important conclusion from this study is the strikingly different stages of development in central, midperipheral, and far peripheral retina over much of human prenatal life. The IPL forms first in the fovea at Fwk 8 and then rapidly develops across the retina, reaching both nasal and temporal edges around midgestation. By contrast, the OPL is much slower to appear. It is a narrow, clear layer in the foveal center at Fwk 11–13 when the fovea is the only retinal region containing all 5 adult layers. Over the next 2 months, the OPL develops slowly outside the fovea, not covering the ~3 mm from fovea to the nasal side of the optic nerve until ~Fwk 20. This is 4–6 weeks after the IPL is present near the optic nerve. However, once the OPL reaches the 20 degree eccentricity of the optic nerve, it develops rapidly, covering the peripheral retina by Fwk 30. This is accompanied somewhat later by maturation of the photoreceptors. In the periphery, the subretinal space contains a mature interphotoreceptor matrix with short photoreceptor inner segments but no outer segments and a thin OPL at Fwk 28.10 Outer segments on both rods and cones are not present near the retinal edge until around birth3,4 and these continue to grow in length for some months after birth.11 Thus all retinal layers are present to the far periphery before birth, but are far from mature.

Given the difficulty in obtaining normal, well-preserved human prenatal eyes, we are forced to work with small numbers. In addition, aging of fetuses is dependent on the source and can vary by 1–2 weeks. However, given these factors, most of our data are quite consistent (Figure 1, Left; Tables 1 and 2). In Table 2, 1 Fwk 15 eye that had a relatively short retinal length but excellent preservation showed an accelerated OPL development, for which we have no explanation.

What are the factors encouraging IPL and OPL development? Neuronal generation definitely shows a foveal-to-peripheral pattern. LaVail and associates8 demonstrated in Macaca monkey using tritiated thymidine labeling in utero that all neurons and Müller glia are generated first in the fovea. Cell generation moves sequentially more peripherally until the last neurons are generated at the retinal edges several months after birth. Provis and associates12 determined the sequence of disappearance of mitotic figures in human retina, which tracks the cessation of neuronal generation. They find that mitotic figures are absent from the fovea and adjacent 0.5 mm by Fwk 14–15, indicating that all cells have been generated in the most central retina. Mitoses are absent in the central 20 degrees by Fwk 20–21. This is the earliest age at which we find that both IPL and OPL are present across central retina. At Fwk 24, the oldest age in the study by Provis and associates,12 many mitotic figures are still present in the peripheral half of the retina, indicating that neuronal generation will occur for some weeks. Thus in both Macaca and human retina cell generation begins very early in the fovea and continues up to or after birth in the far periphery.

These centroperipheral patterns are consistent with layers only forming after all neurons are generated. However, the sequence in which neuronal types are generated does not explain lamination. LaVail and associates8 find that the first generated neurons are cones and horizontal cells, both related to the OPL, and ganglion cells, related to the IPL. The last generated are rods, related to the OPL, and bipolar cells, related to both the OPL and IPL. Thus birth sequence for neuronal types does not seem to drive lamination.

The presence of inner retinal blood vessels is not related to IPL formation because the IPL is near the edge of the retina when the inner retinal blood vessels first emerge from the optic nerve and begin to grow across the retinal surface.13,14 A causal relationship between deeper blood vessels and OPL development is also unlikely because the deep capillaries are still 5–6 mm from the retinal edge at birth.14

In summary, in human retina the IPL reaches the edge by Fwk 18–20 and the OPL by Fwk 30. Only very early in utero events could affect lamination in central retina, but events occurring after Fwk 20 overlap peripheral laminar development, especially of the outer retina.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING/SUPPORT: THIS WORK WAS PARTIALLY SUPPORTED BY THE VISION CORE NIH GRANT EY0001730 TO THE UNIVERSITY of Washington. Financial disclosures: The following author has no financial disclosures: Anita Hendrickson. All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

The technical support of Daniel Possin and Toni Haun, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Washington, is greatly appreciated.

Biography

Anita Hendrickson is Professor Emerita of Biological Structure and Ophthalmology at the University of Washington—Seattle. She joined the latter in 1967, rose through the ranks to Professor, then chaired the Department of Biological Structure up to 2000. She has done extensive research on primate retinal development including human foveal development. Honors include the Proctor Medal from the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology and the Retina Research Award of the International Society for Eye Research.

References

- 1.Mann I. The Development of the Human Eye. 3rd. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuodelis C, Hendrickson A. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of the human fovea during development. Vision Res. 1986;26(6):847–855. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(86)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao M, Hendrickson A. Spatial and temporal expression of short, long/medium or both opsins in human fetal cones. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425:545–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendrickson A, Bumsted-O’Brien K, Natoli R, Ramamurthy V, Possin D, Provis J. Rod photoreceptor differentiation in fetal and infant human retina. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87(5):415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrickson A, Possin D, Vajzovic L, Toth CA. Histologic development of the human fovea from midgestation to maturity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(5):767–778.e762. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vajzovic L, Hendrickson AE, O’Connell RV, et al. Maturation of the human fovea: correlation of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings with histology. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(5):779–789.e772. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubis AM, Costakos DM, Subramaniam CD, et al. Evaluation of normal human foveal development using optical coherence tomography and histologic examination. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(10):1291–1300. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Vail MM, Rapaport DH, Rakic P. Cytogenesis in the monkey retina. J Comp Neurol. 1991;309:86–114. doi: 10.1002/cne.903090107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehlers N, Matthiessen ME, Andersen H. The prenatal growth of the human eye. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1968;46(3):329–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1968.tb02813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson AT, Kretzer FL, Hittner HM, Glazebrook PA, Bridges CD, Lam DM. Development of the subretinal space in the preterm human eye: ultrastructural and immunocytochemical studies. J Comp Neurol. 1985;233(4):497–505. doi: 10.1002/cne.902330409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendrickson A, Drucker D. The development of parafoveal and mid-peripheral human retina. Behav Brain Res. 1992;49(1):21–31. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Provis JM, van Driel D, Billson FA, Russell P. Development of the human retina: patterns of cell distribution and redistribution in the ganglion cell layer. J Comp Neurol. 1985;233(4):429–451. doi: 10.1002/cne.902330403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes S, Yang H, Chan-Ling T. Vascularization of the human fetal retina: roles of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(5):1217–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Provis JM. Development of the primate retinal vasculature. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20(6):799–821. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]