Abstract

Background

The reasons for increasing rates of bilateral mastectomy for unilateral breast cancer are incompletely understood and associations of disease stage with bilateral surgery have been inconsistent. We examined associations of clinical and sociodemographic factors, including stage, with surgery type and reconstruction receipt among women with breast cancer.

Patients/Methods

We surveyed a diverse population-based sample of women from northern California cancer registries with stage 0–III breast cancer diagnosed during 2010–2011 (participation rate=68.5%). Using multinomial logistic regression, we examined factors associated with bilateral and unilateral mastectomy (vs. breast conservation [BCS]), adjusting for tumor and sociodemographic characteristics. In a second model, we examined factors associated with reconstruction for mastectomy-treated patients.

Results

Among 487 participants, 58% had BCS, 32% had unilateral mastectomy, and 10% underwent bilateral mastectomy. In adjusted analyses, women with stage III (vs. stage 0) cancers had higher odds of bilateral mastectomy (odds ratio [O.R]=8.28; 95% Confidence Interval=2.32–29.50); women with stage II and III (vs. stage 0) disease had higher odds of unilateral mastectomy. Higher (vs. lower) income was also associated with bilateral mastectomy, while age ≥60 (vs. <50) was associated with lower odds of bilateral surgery. Among mastectomy-treated patients (n=206), bilateral mastectomy, unmarried status, higher education and income were all associated with reconstruction (Ps<0.05).

Conclusion

In this population-based cohort, women with the greatest risk of distant recurrence were most likely to undergo bilateral mastectomy despite a lack of clear medical benefit, raising concern for over-treatment. Our findings highlight the need for interventions to assure women are making informed surgical decisions.

Keywords: bilateral mastectomy, reconstruction, stage, breast cancer

INTRODUCTION

Rates of mastectomy and contralateral mastectomy for patients with cancer are on the rise1–11 despite strong evidence of equivalent long-term survival for breast preservation (BCS) and mastectomy,12, 13 international consensus for BCS as the preferred therapy when possible,14, 15 and initial increasing frequency of BCS following consensus statements.1, 2 Although the reasons for higher rates of unilateral and bilateral mastectomy are incompletely understood, younger patient age, peace of mind, higher socioeconomic status (SES), white race, regional variation, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), family history/genetics, celebrity/media impact, and cosmetic concerns/symmetry have been associated with bilateral mastectomy.5–11, 16–30 Past studies have varied in their sample size, geographic coverage, and information about reconstruction; they are also frequently registry-based and lacking individualized information on socio-demographic factors. Past studies have also had inconsistent findings for receipt of bilateral surgery by stage, and are limited by use of older data.9, 10, 29 Understanding how disease stage may impact surgical decision making may provide important information on how to best frame discussions with patients around risks and benefits of local therapy options.

In this study, we surveyed a diverse sample of women with breast cancer diagnosed in 2010–2011 in northern California about their cancer treatment. We examined patient clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with receipt of unilateral and bilateral mastectomy as well as reconstruction for mastectomy-treated patients.

METHODS

Study Population

As previously described31 we identified 1,118 white, black, or Hispanic women from Regions 1/8 (San Francisco/Santa Clara) and Region 3 (Sacramento) of the California Cancer Registry (CCR) who were diagnosed with stage 0-III breast cancer during 2010–2011. The study was approved by the CCR, the California Health and Human Services Agency Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, and Harvard Medical School’s Committee on Human Studies.

Survey Administration and Patient Enrollment

We mailed letters to eligible patients in English and Spanish inviting them to participate in a survey about their breast cancer care. Potential participants were interviewed by phone after providing verbal informed consent. Interviews were administered in English or Spanish by trained study staff using computer assisted telephone interview software; seventy of 136 Hispanic women were interviewed in Spanish. Participants received $20 upon interview completion.

Survey

Participants were asked general questions about their breast cancer diagnosis and treatment and also reported race/ethnicity, educational attainment,32 insurance coverage at diagnosis,32 health literacy,33 and comorbidity.32, 34 We obtained tumor and treatment information from the CCR, including surgical type and cancer stage. The survey instrument was published previously.35

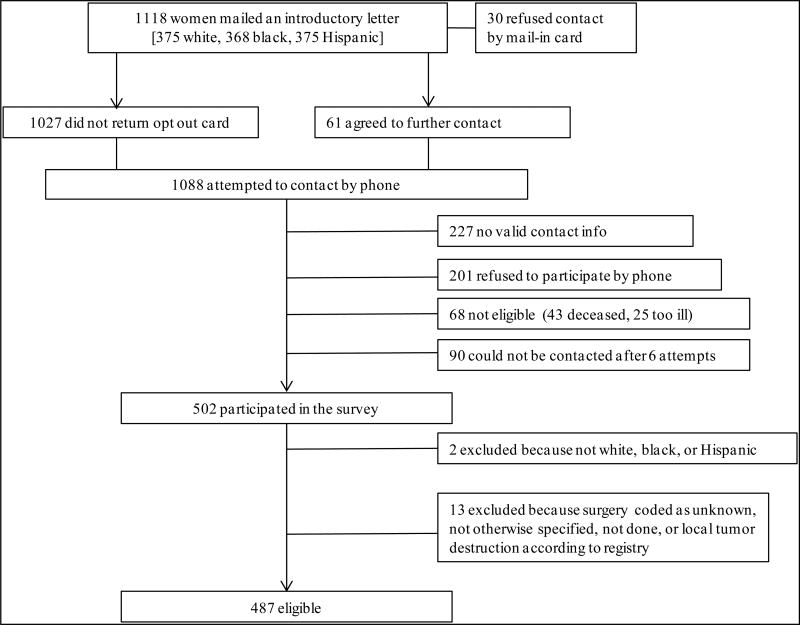

Survey Response Rates

As shown in Figure 1, among 1,118 patients, 231 refused participation (30 sent opt out card, 201 refused by phone), 317 could not be reached (227 no valid contact information, 90 could not be contacted after 6 attempts), and 68 were deceased/too ill; 502 women responded, for an American Association for a Public Opinion Research36 response rate of 47.8%. The participation rate among those for whom we had contact information was 68.5%. Respondents had similar baseline demographic and tumor characteristics as non-respondents, except respondents were younger (mean age=58 vs. 64; p<.0001). Because our survey focused on care for white, black, and Hispanic patients, two women who self-identified as Asian were excluded. We excluded 13 women whose type of cancer-directed surgery was coded as unknown, not otherwise specified (NOS), not done, or local tumor destruction according to the CCR. The final analytic cohort included 487 women, all of whom had unilateral cancers according to the CCR. Interviews for the 502 women were conducted between 1/17/02 and 12/3/13 with a mean time from diagnosis to interview of 2.4 years (range 0.2–4.7 years).

Figure 1. Schema for study enrollment.

American Association for a Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Response Rate36 = 502/(1118-68) = 47.8% Participation Rate = 502/(1118-68-317) = 68.5%

Variables of Interest

The outcome of interest was the type of surgery received as defined by the CCR. We categorized surgery as (1) BCS (partial mastectomy, less than total mastectomy, lumpectomy or excisional biopsy, re-excision of biopsy site, segmental mastectomy), (2) unilateral mastectomy with reconstruction (total [simple] mastectomy, modified radical mastectomy [MRM], or radical mastectomy all either with reconstruction, tissue, implant, or combined tissue/implant and without removal of the contralateral breast), (3) unilateral mastectomy without reconstruction (subcutaneous mastectomy, total [simple] mastectomy MRM, radical mastectomy, extended radical mastectomy all without reconstruction or removal of contralateral breast, (4) bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction (total [simple] mastectomy or MRM with removal of contralateral breast, all with reconstruction, tissue, implant, or combined tissue/implant), and (5) bilateral mastectomy without reconstruction. We examined receipt of BCS, unilateral mastectomy, and bilateral mastectomy (regardless of reconstruction). We also assessed reconstruction among women who underwent bilateral or unilateral mastectomy.

Independent Variables

We defined American Joint Commission on Cancer, 6th edition stage using CCR data. Control variables of interest were selected a priori based on clinical relevance to surgery selection and/or previously reported associations with bilateral surgery and were categorized as per Table 1. These variables included self-reported race/ethnicity, age, marital status, insurance status at diagnosis, number of comorbidities32, 34 (prior other cancer, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, chronic lung disease, kidney problem, depression/psychiatric problems), educational attainment, household income over the last year, and mean health literacy score.33

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by surgery received (n=487)

| Characteristic | Breast-conserving surgery (n=281) |

Unilateral mastectomy a (n=155) |

Bilateral Mastectomy a (n=51) |

P-value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Stagec | <0.0001 | |||

| 0 [n=86] | 59 (69) | 21 (24) | 6 (7) | |

| I [n=198] | 134 (68) | 49 (25) | 15 (8) | |

| II [n=157] | 76 (48) | 61 (39) | 20 (13) | |

| III [n=46] | 12 (26) | 24 (52) | 10 (22) | |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.028 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white [n=220] | 126 (57) | 61 (28) | 33 (15) | |

| Non-Hispanic black [n=132] | 73 (55) | 50 (38) | 9 (7) | |

| Hispanic [n=135] | 82 (61) | 44 (33) | 9 (7) | |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 0.012 | |||

| <50 [n=124] | 60 (48) | 42 (34) | 22 (18) | |

| 50–59 [n=152] | 90 (59) | 46 (30) | 16 (11) | |

| 60+ [n=211] | 131 (62) | 67 (32) | 13 (6) | |

|

| ||||

| Marital status | 0.109 | |||

| Married [n=277] | 154 (56) | 87 (31) | 36 (13) | |

| Unmarried/unknown [n=210] | 127 (60) | 68 (32) | 15 (7) | |

|

| ||||

| Comorbidity score d | 0.884 | |||

| 0 [n=195] | 112 (58) | 62 (32) | 21 (11) | |

| 1 [n=178] | 101 (57) | 56 (31) | 21 (12) | |

| 2+ [n=114] | 68 (60) | 37 (32) | 9 (8) | |

|

| ||||

| Educational attainment | 0.018 | |||

| High school or less [n=163] | 89 (55) | 63 (39) | 11 (7) | |

| Some college [n=153] | 96 (63) | 44 (29) | 13 (9) | |

| College graduate [n=171] | 96 (56) | 48 (28) | 27 (16) | |

|

| ||||

| Household Income | 0.002 | |||

| <$20,000 [n=97] | 55 (57) | 38 (39) | 4 (4) | |

| $20,000-$39,999 [n=89] | 51 (57) | 33 (37) | 5 (6) | |

| $40,000-$59,999 [n=73] | 44 (60) | 22 (30) | 7 (10) | |

| ≥$60,000 [n=178] | 100 (56) | 45 (25) | 33 (19) | |

| Don’t know [n=50] | 31 (62) | 17 (34) | 2 (4) | |

|

| ||||

| Insurance at diagnosis | 0.148 | |||

| Yes [n=460] | 270 (59) | 142 (31) | 48 (10) | |

| No [n=27] | 11 (41) | 13 (48) | 3 (11) | |

|

| ||||

| Average health literacy scoree (SD) | 1.80 (1.07) | 1.82 (1.02) | 1.57 (1.00) | 0.293 |

Abbreviations: SD=standard deviation

With or without reconstruction

Using chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for the health literacy score; bolded results are significant with P<0.05

Using cancer registry data; one case reported as stage IV was categorized as stage III

Comorbidity was assessed by adding the number of self-reported medical conditions32, 34 including other cancers, diabetes, heart attack, stroke, emphysema/chronic bronchitis/asthma/other chronic lung disease, kidney problems, depression/other psychiatric illness.

Health literacy was defined using a validated, 3-item screening tool:33 (1) “How confident are you filling out medical forms,” (2) “How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition?,” and (3) “How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials?” Responses used a 5-item Likert scale. After reversing responses for the first item, we assigned each answer a score of 1–5 (lower numbers reflect most confidence/fewest problems) and averaged the three scores. Lower scores indicate better literacy.

Statistical Analysis

We used χ2 tests to assess differences in surgical procedures by baseline characteristics, and Kruskal Wallis tests to assess differences by mean health literacy scores. We used multinomial logistic regression to assess the probability of having unilateral or bilateral mastectomy versus BCS, adjusting for the control variables listed above.

In a second model, we used logistic regression to examine receipt of reconstruction among mastectomy-treated patients (n=206), adjusting for the same variables listed above and also including a variable for bilateral (vs. unilateral) mastectomy.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

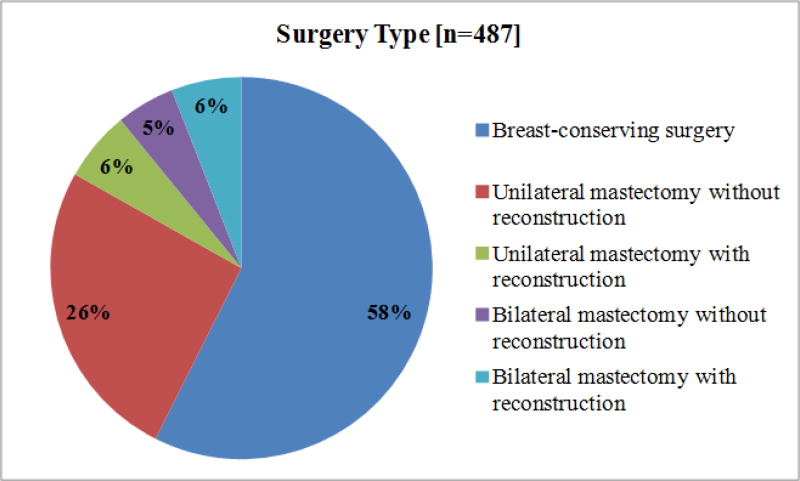

Baseline characteristics by surgery type for the 487 participants are shown in Table 1. Most women underwent BCS (58%), 32% underwent unilateral mastectomy, and 10% had bilateral mastectomy. Figure 2 shows surgery type and whether reconstruction was performed. Among the 206 mastectomy-treated patients, 25% had bilateral mastectomy and 27% of all mastectomy-treated women underwent reconstruction. For those who underwent unilateral mastectomy (n=155), 28 (18%) had reconstruction while 27 of the 51 patients (53%) having bilateral mastectomy had reconstruction.

Figure 2. Proportion of patients who underwent each type of surgery, including reconstruction a.

a Note, because of rounding, the total percentage of women undergoing bilateral mastectomy is 10%

Unadjusted results for surgery type

In unadjusted results (Table 1), more advanced stage was associated with higher rates of both unilateral and bilateral mastectomy, with 74% of women with stage III disease undergoing these procedures. Among mastectomy-treated patients with stage III disease, 29% had bilateral mastectomy. Hispanic patients had the highest rates of BCS (61%), blacks had the highest rates of unilateral mastectomy (38%), and whites had the highest rates of bilateral surgery (15%, p=0.028). Patients aged <50 had higher rates of bilateral surgery than other age groups (18% vs. 6% in women ages ≥60, p=0.012) and those with higher educational attainment and household income also had more bilateral surgery than women of lower SES, who had higher rates of unilateral mastectomy than other groups. The differences in procedures by income were primarily observed among those undergoing mastectomy (i.e. unilateral vs. bilateral surgery), with relatively equal numbers of women undergoing BCS across income groups (56–60%).

Adjusted results for surgery type

In adjusted analyses (Table 2), stage II disease (vs. 0) was statistically significantly associated with higher odds for unilateral (OR=2.21, 95% CI=1.19–4.11) but not bilateral mastectomy (OR=2.48, 95% CI=0.88–6.96) and stage III disease (vs. 0) was strongly associated with both unilateral (OR=5.31, 95% CI=2.20–12.80) and bilateral (OR=8.28, 95% CI=2.32–29.50) mastectomy. We also observed lower odds of bilateral surgery for women aged ≥60 ([adjusted odds ratio] OR=0.35, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]=0.15–0.84 vs. ages <50]) and higher odds of bilateral surgery for women with household incomes ≥$60,000/year (vs. incomes <$20,000/year; OR=5.19, 95% CI=1.18–22.82).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds for receipt of unilateral mastectomy or bilateral mastectomy (vs. breast-conserving surgery) [left columns] and for receipt of reconstruction [right columns] a, b

| Unilateral Mastectomy | Bilateral Mastectomy | Reconstruction receipt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N=483 [entire cohort] |

N=206 [mastectomy treated] |

|||||

|

| ||||||

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

|

| ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- |

| I | 0.95 | 0.51–1.75 | 1.31 | 0.46–3.70 | 1.43 | 0.45–4.57 |

| II | 2.21 | 1.19–4.11 | 2.48 | 0.88–6.96 | 0.52 | 0.16–1.63 |

| III | 5.31 | 2.20–12.80 | 8.28 | 2.32–29.50 | 1.09 | 0.27–4.45 |

|

| ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.48 | 0.87–2.50 | 0.61 | 0.25–1.46 | 0.34 | 0.11–1.04 |

| Hispanic | 0.94 | 0.53–1.66 | 0.44 | 0.17–1.10 | 2.30 | 0.75–7.04 |

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <50 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- |

| 50–59 | 0.84 | 0.48–1.49 | 0.52 | 0.24–1.13 | 0.47 | 0.18–1.22 |

| 60+ | 0.87 | 0.49–1.53 | 0.35 | 0.15–0.84 | 0.40 | 0.14–1.13 |

|

| ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- |

| Unmarried/unknown | 0.69 | 0.42–1.12 | 0.96 | 0.43–2.11 | 3.71 | 1.37–10.06 |

|

| ||||||

| Comorbidity score | ||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- |

| 1 | 1.06 | 0.66–1.71 | 1.42 | 0.69–2.92 | 1.44 | 0.61–3.39 |

| 2+ | 1.06 | 0.60–1.87 | 1.29 | 0.51–3.27 | 0.59 | 0.18–1.91 |

|

| ||||||

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| High school or less | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- |

| Some college | 0.59 | 0.33–1.06 | 0.55 | 0.20–1.51 | 1.55 | 0.47–5.03 |

| College graduate | 0.65 | 0.36–1.18 | 0.92 | 0.36–2.40 | 4.33 | 1.37–13.71 |

|

| ||||||

| Household Income | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- |

| $20,000-$39,999 | 1.06 | 0.54–2.06 | 1.66 | 0.38–7.31 | 7.89 | 1.35–46.12 |

| $40,000-$59,999 | 0.93 | 0.42–2.06 | 3.31 | 0.70–15.64 | 9.86 | 1.34–72.83 |

| ≥$60,000 | 0.75 | 0.35–1.60 | 5.19 | 1.18–22.82 | 14.95 | 2.11–105.88 |

| Don’t know | 0.83 | 0.36–1.92 | 1.06 | 0.15–7.44 | 1.64 | 0.10–25.75 |

|

| ||||||

| Insurance at diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- |

| No | 1.49 | 0.58–3.78 | 2.98 | 0.64–13.95 | 3.56 | 0.63–20.10 |

|

| ||||||

| Average health literacy score | 0.95 | 0.75–1.19 | 1.04 | 0.69–1.55 | 0.95 | 0.60–1.53 |

|

| ||||||

| Bilateral mastectomy | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| No | 1.00 | -- | ||||

| Yes | 3.53 | 1.52–8.18 | ||||

Abbreviation: CI=confidence interval

Adjusted for all variables in the table

Bold = P<0.05

Reconstruction

In models examining receipt of reconstruction among 206 mastectomy-treated patients (Table 2), women who were unmarried (vs. married, OR=1.37, 95% CI=1.37–10.06), college graduates (vs. high school, OR=4.33, 95% CI=1.37–13.71), had higher income (vs. <$20,000, OR=7.89, 95% CI=1.35–46.12 for $20,000–39,999; OR=9.86, 95% CI=1.34–72.83 for $40,000–59,999; OR=14.95, 95% CI=2.11–105.88 for ≥$60,000) and had bilateral (vs. unilateral, OR=3.53, 95% CI=1.52–8.18) mastectomy were more likely to have reconstruction. Stage was not significantly associated with reconstruction.

DISCUSSION

Rates of bilateral mastectomy for unilateral breast cancer have been increasing in recent years despite consistent evidence that this procedure does not improve long term outcomes for most patients8, 37, 38 and may lead to long term issues with body image.39, 40 In a large, diverse and modern cohort of breast cancer patients, we observed relatively high rates of bilateral mastectomy for women with unilateral, stage 0-III breast cancers: 10% underwent bilateral mastectomy and 25% of all patients undergoing mastectomy had bilateral surgery. Approximately 18% of women had reconstruction for unilateral mastectomy, whereas nearly 53% of patients with bilateral mastectomy had reconstruction. For women with stage III disease, the rates of bilateral mastectomy among mastectomy-treated patients was even higher than the overall sample, with 29% having bilateral surgery. Prior studies have reported rates of bilateral mastectomy ranging from 3–30%, 8, 9, 18, 19 and likely differ due to differences in settings (i.e. single institution, population-based, hospital-based), ages of women included, and the time periods analyzed. In addition, direct comparisons of surgical procedures across studies are limited by differences in the surgical outcomes of interest, with some studies examining bilateral mastectomy for those who undergo mastectomy only while other studies compare all procedures separately. Consistent with prior work, we observed higher rates of bilateral mastectomy for young women, white women, and those with higher income7, 10 and strong associations for reconstruction with higher educational attainment and annual income.41–43

We also noted strong associations for bilateral surgery with stage III (vs. stage 0) disease, which has been less consistently observed by others. For example, Yao et al.10 and Ashfaq et al.29 reported lower odds of bilateral surgery with increasing stage and Tuttle et al.9 observed higher rates of bilateral surgery for stage III vs. I disease; several other papers have shown no association of stage with bilateral mastectomy. Our findings for stage are similar to the Tuttle findings but are in a more recent population-based cohort. The higher rates of bilateral mastectomy among stage III patients with unilateral breast cancer are surprising given the well documented lack of survival advantage for bilateral surgery.8, 37, 38 Furthermore, patients with higher-stage disease may be least likely to benefit from contralateral breast surgery because their greatest risk is distant recurrence rather than new, contralateral disease, in contrast to the negligible competing systemic recurrence risks for patients with DCIS. This finding may be explained by women with higher-risk disease wishing to be as ‘aggressive’ as possible to eliminate future risk or having more anxiety-driven decisions.26, 30 It may also derive from a desire to avoid ever again going through the aggressive systemic treatment they need for their higher risk index cancer.26 Past research suggests that even though women may know that bilateral mastectomy will not improve survival across populations, they cite improvement in survival as a reason for choosing bilateral surgery,26 suggesting a possible disconnect in processing the facts and emotions surrounding surgical decision-making. Patients should be counseled about these issues during the decision-making process, with conversations tailored to an individual’s potential risk and benefit of bilateral surgery, particularly for those with who have a higher risk for distant recurrence.

An alternate explanation for our finding of higher rates of bilateral mastectomy among stage III patients may be related to improved reconstructive options and insurance coverage for reconstructive procedures in recent years, making bilateral mastectomy followed by reconstruction more appealing than unilateral mastectomy, and essentially replacing the unilateral mastectomy option for some women.5, 29 In other words, if a woman requires a mastectomy or chooses mastectomy for a higher-risk tumor, she is more likely to consider contralateral surgery than a woman undergoing BCS. The higher odds of reconstruction we observed for women undergoing bilateral (vs. unilateral) mastectomy are consistent with this hypothesis.

Our results add to the literature supporting a need to better understand the breast surgery decision-making process and to design interventions in this area. Patients considering bilateral surgery should be counseled about the additional risks associated with more aggressive surgical procedures,44–46 the burdens of multi-stage surgeries required during the reconstructive process, the potential impact on sexuality and body image,39, 40 and the lack of clear medical benefits for most patients.8, 37, 38 Recent evidence showing higher rates of BCS for women seen in a multidisciplinary setting (vs. individual providers) suggests that a team of providers may reduce the number of women receiving bilateral mastectomy.47 Decision tools may also be effective interventions;48 large-scale studies examining the utility of such tools are underway. Insurers are now playing a larger role in these decisions as well; some payers have restricted coverage for bilateral mastectomy to women with a clear ‘medical necessity’ (e.g. a known genetic mutation or history of chest irradiation, who have markedly increased risk for contralateral cancers).49–51 In a climate where reducing health care costs is increasingly important, more insurers may impose similar restrictions.

We recognize several study limitations. First, we lacked information on patient preferences, genetic testing results, family history, provider recommendations, surgical options provided to patients, and whether patients met with a plastic surgeon. Second, surveyed patients resided in northern California only and may not be generalizable to other regions. Furthermore, regional and institutional variation in availability of plastic surgeons and differing care styles are well documented and may not be well represented in this study where many women were treated in two large hospital systems.5, 41, 52, 53 Third, although registry data have been demonstrated to accurately capture surgical treatments,54 it is possible that some procedures were miscoded or missed because they were completed long after a patient’s diagnosis (i.e. delayed reconstruction occurring more than a year after diagnosis). Nevertheless, our survey included a large and diverse, recently diagnosed population-based sample of women with individual information on SES, health literacy, insurance, and reconstruction, allowing for exploration of these important outcomes.

In conclusion, we observed relatively high rates of bilateral mastectomy for women with stage 0-III breast cancer. Among other previously described factors associated with bilateral mastectomy, stage III disease was significantly associated with bilateral mastectomy. Given the lack of medical benefits for contralateral surgery, these findings highlight the need for enhanced discussions and decision tools during the surgical decision-making process, and particularly for women with higher-stage cancers.

CLINICAL PRACTICE POINTS.

Rates of bilateral mastectomy for unilateral breast cancer are increasing nationwide and the reasons for this are incompletely understood. Past associations of disease stage with receipt of bilateral surgery for unilateral cancers are inconsistent. We surveyed a diverse sample of 483 women in northern California registries and examined factors associated with receipt of unilateral and bilateral mastectomy compared with breast conversation (BCS), including disease stage. In this cohort, 10% of women underwent bilateral mastectomy, 58% had BCS, and 32% had unilateral mastectomy. In adjusted analyses, among other factors previously reported to be associated with bilateral mastectomy, we noted significantly higher odds of bilateral mastectomy for stage III (vs. stage 0) cancers. This raises concern for over-treatment given that most women will not derive a clear medical benefit with bilateral mastectomy. Our findings highlight the need for interventions to assure women are making informed surgical decisions.

Acknowledgments

We thank all women who participated in interviews, the Cancer Registry of Greater California, and Ana Guerrero for assistance with interviews.

FUNDING: Susan G. Komen. Support also received by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant (RAF) and a K24CA181510 (NLK) from the National Cancer Institute.

DATA: The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement U58DP003862-01 awarded to the California Department of Public Health. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: none

References

- 1.Dragun AE, Pan J, Riley EC, et al. Increasing use of elective mastectomy and contralateral prophylactic surgery among breast conservation candidates: a 14-year report from a comprehensive cancer center. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36(4):375–380. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318248da47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dragun AE, Huang B, Tucker TC, Spanos WJ. Increasing mastectomy rates among all age groups for early stage breast cancer: a 10-year study of surgical choice. Breast J. 2012;18(4):318–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2012.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuire KP, Santillan AA, Kaur P, et al. Are mastectomies on the rise? A 13-year trend analysis of the selection of mastectomy versus breast conservation therapy in 5865 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(10):2682–2690. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0635-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahmood U, Hanlon AL, Koshy M, et al. Increasing national mastectomy rates for the treatment of early stage breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(5):1436–1443. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2732-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kummerow KL, Du L, Penson DF, Shyr Y, Hooks MA. Nationwide trends in mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA surgery. 2015;150(1):9–16. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tracy MS, Rosenberg SM, Dominici L, Partridge AH. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with breast cancer: trends, predictors, and areas for future research. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140(3):447–452. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2643-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawley ST, Jagsi R, Morrow M, et al. Social and Clinical Determinants of Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy. JAMA surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurian AW, Lichtensztajn DY, Keegan TH, Nelson DO, Clarke CA, Gomez SL. Use of and mortality after bilateral mastectomy compared with other surgical treatments for breast cancer in California, 1998–2011. JAMA. 2014;312(9):902–914. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuttle TM, Habermann EB, Grund EH, Morris TJ, Virnig BA. Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: a trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5203–5209. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao K, Stewart AK, Winchester DJ, Winchester DP. Trends in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for unilateral cancer: a report from the National Cancer Data Base, 1998–2007. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(10):2554–2562. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yakoub D, Avisar E, Koru-Sengul T, et al. Factors associated with contralateral preventive mastectomy. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2015;7:1–8. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S72737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arriagada R, Le MG, Rochard F, Contesso G. Conservative treatment versus mastectomy in early breast cancer: patterns of failure with 15 years of follow-up data. Institut Gustave-Roussy Breast Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(5):1558–1564. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr; NIH Consensus Development Conference on the Treatment of Early-Stage Breast Cancer; June 18–21, 1990; 1992. pp. 1–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA; NIH consensus conference; 1991. pp. 391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinell-White XA, Kolegraff K, Carlson GW. Predictors of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and the impact on breast reconstruction. Annals of plastic surgery. 2014;72(6):S153–157. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutter CE, Park HS, Killelea BK, Evans SB. Growing Use of Mastectomy for Ductal Carcinoma-In Situ of the Breast Among Young Women in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arrington AK, Jarosek SL, Virnig BA, Habermann EB, Tuttle TM. Patient and surgeon characteristics associated with increased use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in patients with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(10):2697–2704. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0641-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuttle TM, Jarosek S, Habermann EB, et al. Increasing rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1362–1367. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans DG, Barwell J, Eccles DM, et al. The Angelina Jolie effect: how high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(5):442. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0442-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nancy Reagan's choice of mastectomy seems to have influenced many breast cancer patients. Oncology (Williston Park) 1998;12(5):668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz SJ, Morrow M. The challenge of individualizing treatments for patients with breast cancer. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1379–1380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewster AM, Parker PA. Current knowledge on contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among women with sporadic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2011;16(7):935–941. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson CT, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Choosing where to have major surgery: who makes the decision? Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):242–246. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pesce CE, Liederbach E, Czechura T, Winchester DJ, Yao K. Changing surgical trends in young patients with early stage breast cancer, 2003 to 2010: a report from the National Cancer Data Base. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg SM, Tracy MS, Meyer ME, et al. Perceptions, knowledge, and satisfaction with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among young women with breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(6):373–381. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-6-201309170-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Killelea BK, Long JB, Chagpar AB, et al. Trends and clinical implications of preoperative breast MRI in Medicare beneficiaries with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141(1):155–163. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2656-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nattinger AB, Hoffmann RG, Howell-Pelz A, Goodwin JS. Effect of Nancy Reagan's mastectomy on choice of surgery for breast cancer by US women. JAMA. 1998;279(10):762–766. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.10.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashfaq A, McGhan LJ, Pockaj BA, et al. Impact of breast reconstruction on the decision to undergo contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(9):2934–2940. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker PA, Peterson SK, Bedrosian I, et al. Prospective Study of Surgical Decision-making Processes for Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy in Women With Breast Cancer. Ann Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freedman RA, Kouri EM, West DW, Keating NL. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Knowledge about One’s Breast Cancer Characteristics. Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28977. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34(1):73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freedman RA, Kouri E, West C, Keating NL. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Patients’ Selection of Surgeons and Hospitals for Breast Cancer Surgery. JAMA Oncology. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.20. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Association for Public Opinion Research. [Accessed October 2, 2014]; Response rate: an overview. http://www.aapor.org/Response_Rates_An_Overview1/3720.htm#.VAXD503D–fA.

- 37.Pesce C, Liederbach E, Wang C, Lapin B, Winchester DJ, Yao K. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy provides no survival benefit in young women with estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(10):3231–3239. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3956-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Portschy PR, Kuntz KM, Tuttle TM. Survival outcomes after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a decision analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(8) doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unukovych D, Sandelin K, Liljegren A, et al. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in breast cancer patients with a family history: a prospective 2-years follow-up study of health related quality of life, sexuality and body image. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(17):3150–3156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frost MH, Slezak JM, Tran NV, et al. Satisfaction after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: the significance of mastectomy type, reconstructive complications, and body appearance. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7849–7856. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenberg CC, Schneider EC, Lipsitz SR, et al. Do variations in provider discussions explain socioeconomic disparities in postmastectomy breast reconstruction? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(4):605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christian CK, Niland J, Edge SB, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of the socioeconomic determinants of breast reconstruction: a study of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Ann Surg. 2006;243(2):241–249. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197738.63512.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrow M, Mujahid M, Lantz PM, et al. Correlates of breast reconstruction: results from a population-based study. Cancer. 2005;104(11):2340–2346. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller ME, Czechura T, Martz B, et al. Operative risks associated with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a single institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(13):4113–4120. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osman F, Saleh F, Jackson TD, Corrigan MA, Cil T. Increased postoperative complications in bilateral mastectomy patients compared to unilateral mastectomy: an analysis of the NSQIP database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(10):3212–3217. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unukovych D, Sandelin K, Wickman M, et al. Breast reconstruction in patients with personal and family history of breast cancer undergoing contralateral prophylactic mastectomy, a 10-year experience. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(7):934–941. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.666000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomez CL, Wang P-C, Dawson NA, et al. Multidisciplinary breast cancer care is associated with higher rate of breast conservation in comparison with non-multidisciplinary care; Presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December. 2014; 2014. Abstract P1-16-02. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waljee JF, Rogers MA, Alderman AK. Decision aids and breast cancer: do they influence choice for surgery and knowledge of treatment options? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(9):1067–1073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Florida Blue, in the pursuit of health. Medical Coverage Guidelines (Medical Policies) [accessed 3/5/15];Subject: Prophylactic Mastectomy. http://mcgs.bcbsfl.com/?doc=Prophylactic%20Mastectomy.

- 50.BlueCross BlueShieild of Mississippi. [accessed April 15, 2015];Prophylactic Mastectomy. https://www.bcbsms.com/index.php?q=provider-medical-policy-search.html&action=viewPolicy&path=%2Fpolicy%2Femed%2FProphylactic_Mastectomy.html.

- 51.Blue Cross of Idaho. [Accessed April 15, 2015];Prophylactic Mastectomy. https://www.bcidaho.com/providers/medical_policies/sur/mp_70109.asp.

- 52.In H, Jiang W, Lipsitz SR, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Greenberg CC. Variation in the utilization of reconstruction following mastectomy in elderly women. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(6):1872–1879. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2821-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenberg CC, Lipsitz SR, Hughes ME, et al. Institutional variation in the surgical treatment of breast cancer: a study of the NCCN. Ann Surg. 2011;254(2):339–345. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182263bb0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malin JL, Kahn KL, Adams J, Kwan L, Laouri M, Ganz PA. Validity of cancer registry data for measuring the quality of breast cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(11):835–844. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]