Abstract

In contrast to the general belief, endothelial cell (EC) metabolism has recently been identified as a driver rather than a bystander effect of angiogenesis in health and disease. Indeed, different EC subtypes present with distinct metabolic properties, which determine their function in angiogenesis upon growth factor stimulation. One of the main stimulators of angiogenesis is hypoxia, frequently observed in disease settings such as cancer and atherosclerosis. It has long been established that hypoxic signalling and metabolism changes are highly interlinked. In this review, we will provide an overview of the literature and recent findings on hypoxia‐driven EC function and metabolism in health and disease. We summarize evidence on metabolic crosstalk between different hypoxic cell types with ECs and suggest new metabolic targets.

Keywords: cancer, cardiovascular disease, endothelial cell, hypoxia, metabolism

Subject Categories: Metabolism, Molecular Biology of Disease, Vascular Biology & Angiogenesis

Endothelial cell function and vessel formation in health

Endothelial cells (ECs) line the vessels of the (cardio)‐vascular systems and play a major role in maintaining oxygen and nutrient supply to all tissues in the body. Normal adult ECs remain largely quiescent in health, but can become rapidly activated in response to injury or pathological conditions, where angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels) is required to facilitate delivery of oxygen and nutrients to (hypoxic) tissues. Angiogenesis is governed by three main EC subtypes, which carry out specialized tasks in angiogenesis and EC function (Potente et al, 2011): migratory tip cells, which guide the growing vascular sprout in response to growth factors; stalk cells, which proliferate and elongate the sprout; and quiescent phalanx cells, identified by their cobblestone‐like shape, which are present in established vessels and function to regulate vascular homeostasis and endothelial barrier function (Fig 1A) (Carmeliet, 2005; Mazzone et al, 2009; Potente et al, 2011).

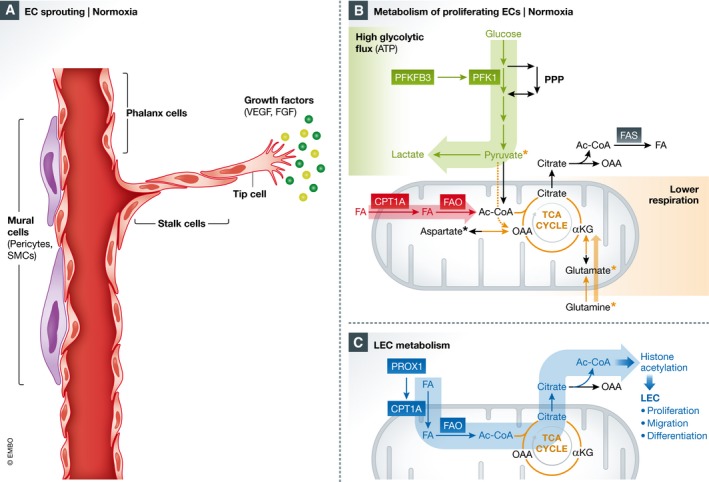

Figure 1. Endothelial and lymphatic cell metabolism in normoxia.

(A) Endothelial cells (ECs) line blood vessels and remain quiescent for years. In these vessels, ECs, termed phalanx cells, are maintained in a quiescent state, in part through the interaction of mural cells such as pericytes and smooth muscle cells (SMCs), which stabilize the vessel, strengthening intercellular junctions and improving barrier function. Upon stimulus to extracellular cues such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or fibroblast growth factor (FGF), ECs switch to an angiogenic phenotype towards the growth factor gradient. (B) In normoxia, endothelial cells (ECs) are characterized by high rates of glycolytic flux, where glucose is metabolized to pyruvate and lactate. 6‐phosphofructokinase/2,6‐bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) is upregulated during angiogenesis and regulates glycolytic flux through the production of fructose 2,6‐bisphosphate, an allosteric regulator of phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1), a rate‐limiting step of glycolysis. Glucose intermediates are also used to fuel the side‐glycolytic pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), important for redox homeostasis. ECs also utilize fatty acids (FAs), which are transported to the mitochondria by carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (CPT1A), a rate‐controlling step of fatty acid β‐oxidation (FAO). FAO produces acetyl‐CoA (Ac‐CoA), which contributes to sustaining the TCA cycle, in conjunction with anaplerotic substrates such as pyruvate, glutamate/glutamine or aspartate (as indicated with *). (C) During venous EC‐to‐lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC) differentiation, prospero homeobox transcription factor 1 (PROX1), an essential transcription factor necessary for LEC differentiation, directly binds to the CPT1A gene/promoter, increasing FA mitochondrial import and FAO. This increased FAO in LECs is utilized to fuel histone acetylation through the export of citrate, where it regenerates Ac‐CoA in the cytosol. This histone acetylation is targeted towards lymphatic genes necessary for LEC differentiation, proliferation and migration. α‐KG, α‐ketoglutarate; FAS, fatty acid synthesis; OAA, oxaloacetate.

The most well‐characterized activator of angiogenesis is the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF receptor (VEGFR) 2 is the primary receptor mediating angiogenic signalling, whereas VEGFR1 has primarily been characterized as a decoy receptor (Meyer et al, 2006). VEGF contains a hypoxia‐responsive element (HRE), which is activated in situations of reduced oxygen availability, allowing hypoxic tissues to stimulate angiogenesis to restore oxygen and nutrient supply to hypoxic areas. In the resultant growth factor gradient, VEGF binds to VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) on ECs and induces tip cell formation. Tip cells express delta‐like ligand 4 (DLL4), which binds Notch receptors on neighbouring cells, inducing stalk cell formation. DLL4 signalling induces Notch‐intracellular domain (NICD) to be cleaved in stalk cells, which then reprogrammes the cell to produce VEGFR1 instead of VEGFR2. VEGFR1 has greatly reduced sensitivity to VEGF, thus ensuring stalk cell behaviour (Phng & Gerhardt, 2009). This interaction between tip and stalk cells is dynamic, and continuous cell shuffling from tip to stalk position ensures the most competitive cell, with the highest levels of VEGFR2, to be located at the tip of the sprout (Jakobsson et al, 2010). When two adjacent tip cells come in contact, they can fuse and a lumenized, perfused vessel is formed. Upon maturation of the vessel, ECs then regain a quiescent non‐proliferative phenotype (phalanx cells), with high VEGFR1 levels (Potente et al, 2011).

Endothelial cell metabolism

Glycolysis and glucose metabolism

In recent years, our understanding of EC metabolism has exponentially increased, with cellular metabolic pathways positioned as central mediators of signalling and angiogenesis induction in health and disease. Independent of the EC subtype, arterial, venous, lymphatic and microvascular ECs are highly glycolytic, comparable to the glucose utilization by some cancer cells (De Bock et al, 2013). As well, tumour ECs (TECs) have further increased glycolytic flux compared to normal ECs (Cantelmo et al, 2016). Conceptually, it could be expected that ECs do not rely on oxygen‐dependent metabolism for biomass and energy production in hypoxic areas, in order to minimize oxygen consumption (which would be limited in hypoxia) and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Yet, even in healthy quiescent vasculature with abundant oxygen availability, ECs show high rates of glycolysis, although the status of other metabolic pathways remains to be largely characterized. Glycolysis in ECs is modulated by the enzyme 6‐phosphofructo‐2‐kinase/fructose‐2,6‐bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), an activator of phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1), a rate‐limiting enzyme of glycolysis (Fig 1B). Upon angiogenic stimuli, such as VEGF, ECs nearly double their glycolytic flux, particularly in tip cells (Peters et al, 2009; Parra‐Bonilla et al, 2010; De Bock et al, 2013). This effect is mediated by an upregulation of PFKFB3, which, in turn, can overrule stalk cell‐promoting Notch signalling (De Bock et al, 2013) (Fig 1B). PFKFB3 is the most abundant PFKFB isoenzyme in all EC subtypes studied thus far (venous, arterial, microvascular and haemangioma ECs) and when silenced, the levels of the PFKFB3 catalysed product fructose 2,6‐bisphosphate (F2,6BP) decrease, resulting in a reduction in glycolytic flux by about 35% (De Bock et al, 2013). In concert, DII4 stimulation reduces glycolytic flux by downregulating PFKFB3 protein levels (De Bock et al, 2013). Additionally, PFKFB3 and other glycolytic enzymes compartmentalize in lamellipodia and filopodia, where they can associate with F‐actin (De Bock et al, 2013). This enables rapid and localized ATP production during glycolysis in these regions, needed for cytoskeleton remodelling during cell migration and angiogenesis (De Bock et al, 2013). This central role of glycolysis in angiogenesis and EC function makes it an attractive anti‐angiogenic target.

Indeed, ECs rely heavily on glucose but have lower oxidative phosphorylation compared to other oxidative cell types (De Bock et al, 2013). ECs possess only 6–18% of the mitochondrial volume per total cellular volume, compared to cardiomyocytes, which have ~32% mitochondrial volume (reviewed in Tang et al, 2014). As an exception, the mitochondrial content in cerebrovascular ECs at the blood–brain barrier is almost double that of other vascular ECs (Oldendorf et al, 1977), and these ECs can elevate their aerobic respiration in response to shear stress, which induces increased tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycling (Cucullo et al, 2011). Thus, mitochondria in ECs are functional, a finding that has been confirmed in isolated mitochondria when tested for mitochondrial activity and uncoupling (Koziel et al, 2012). In general, ECs are suggested to experience the Crabtree effect, meaning that high glucose levels repress carbohydrate‐ or glutamine‐driven mitochondrial respiration and in some cell lines may increase the oxidation of fatty acids (FAs) (Krutzfeldt et al, 1990; Dagher et al, 2001; Koziel et al, 2012). Another reason why ECs do not have heavy dependence on mitochondrial respiration may be that nitric oxide (NO), predominantly produced in ECs by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), competes with cellular oxygen for the terminal electron transport chain enzyme cytochrome C oxidase, thereby potentially reducing mitochondrial respiration (Brown & Cooper, 1994; Clementi et al, 1998; Galkin et al, 2007).

Glycolytic intermediates can be also shunted to the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (Fig 1B). The HBP uses glucose, glutamine, acetyl‐CoA and uridine to mediate O‐glycosylation and N‐glycosylation and is upregulated both in diabetes and cancers (as reviewed in Slawson et al, 2010). The PPP can also provide ribose units necessary for nucleotide synthesis and produces NADPH, which is used for ROS scavenging (we refer the reader to Riganti et al, 2012). Decreasing the activity of the PPP by targeting its rate‐controlling enzyme glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) using an anti‐sense oligonucleotide reduced VEGF‐induced proliferation, migration and tube formation capacity in ECs (Leopold et al, 2003a). Also, by generating NADPH, the pentose phosphate shunt induces NO production by eNOS and enhances ROS scavenging capacity of ECs (Leopold et al, 2003b).

Endothelial cells can also store excess intracellular glucose in glycogen (Vizan et al, 2009). This excess glycogen is then mobilized in conditions of glucose deprivation, independent of hypoxia. The role of glycogen metabolism in ECs remains obscure, but EC migration and viability are impaired upon inhibition of the rate‐limiting enzyme in glycogen degradation (glycogen phosphorylase) (Vizan et al, 2009).

Glutamine metabolism

Next to glucose‐derived carbons, glutamine metabolism can serve as an anaplerotic substrate for the TCA cycle (DeBerardinis et al, 2008) (Fig 1B). Anaplerosis is the process where glucose, glutamine or amino acids replenish the TCA cycle (Pavlova & Thompson, 2016). In ECs, highest oxidation rates can be observed for glutamine, glutamate and aspartate (Krutzfeldt et al, 1990) (Fig 1B). Glutaminase (GLS) catalyses the conversion of glutamine to glutamate, and increased GLS flux has been observed in cultured ECs from various vascular beds, including microvascular, aortic and venous ECs (Wu et al, 2000). ECs express about 20‐fold higher GLS activity as compared to other cell types with established glutaminolysis rates, such as lymphocytes (Leighton et al, 1987), though this single finding requires confirmation. GLS inhibition, in turn, induces a senescent phenotype in ECs, supporting an EC‐activating role of glutamine metabolism (Unterluggauer et al, 2008). Additionally, glutamine can serve as a source of nitrogen for nucleotide synthesis (reviewed in Cory & Cory, 2006), though this has not been studied in ECs. In other cell types, glutamine contributes to protein synthesis (Hosios et al, 2016). However, overall, aside from these fragmentary reports, the precise role and relevance of glutamine metabolism in vessel sprouting in physiological conditions and in pathological angiogenesis remain unknown.

Fatty acid utilization

In ECs, FAs are metabolized to acetyl‐CoA, which helps to sustain the TCA cycle and dNTP synthesis for EC proliferation in conjunction with an anaplerotic substrate (Schoors et al, 2015) (Fig 1B). Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (CPT1A) is the most abundant isoform of the CPT1 family in ECs and facilitates the transport of FAs into mitochondria for fatty acid β‐oxidation (FAO) (Schoors et al, 2015). Silencing of CPT1A in ECs decreases FAO and dNTP synthesis, resulting in proliferation and vascular sprouting defects in vitro and in vivo (Schoors et al, 2015). ECs differ hereby from multiple other healthy and malignant cell types, which rely mainly on glucose and glutamine metabolism for nucleotide synthesis.

Endothelial cells can synthesize FAs through FA synthesis, which is also important for EC function. Fatty acid synthase (FASN)‐mediated de novo lipogenesis is required for vascular sprouting and permeability and eNOS palmitoylation (Wei et al, 2011). Whether FASN‐dependent palmitoylation also occurs in other targets requires further investigation. Next to FA synthesis, ECs express FA transfer proteins (FATPs) and CD36, which can mediate the active transport of FAs into ECs or across the endothelium. Additionally, FAs can also be taken up from the blood by passive diffusion (Schoors et al, 2015; Wong et al, 2017). However, the balance between endothelial FA utilization and endothelial FA transport to surrounding tissues requires further clarification. Also, whether the utilization of FAs is altered in proliferative and migratory ECs in angiogenesis (i.e. tip and stalk cells) versus quiescent ECs (i.e. phalanx cells) remains to be elucidated.

In lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), the role of FA utilization and FAO has recently been described to differ from blood vascular ECs (Wong et al, 2017) (Fig 1C). LECs line lymphatic vessels, which are important in fluid homeostasis, lipid transport, immune modulation, and are a primary route of metastasis in certain cancer types (Alitalo, 2011). As in blood vascular ECs, LECs also utilize FAO for dNTP synthesis (Wong et al, 2017). Moreover, during venous EC‐to‐LEC differentiation, PROX1 binds to the CPT1A gene and upregulates FAO in LEC differentiation to promote acetyl‐CoA production, not for energy production or redox homeostasis, but rather to support histone acetylation, specifically at lymphatic genes through a PROX1/p300‐dependent interaction (Wong et al, 2017). This FAO‐dependent mechanism is necessary to support lymphatic development and lymphangiogenesis in vivo (Wong et al, 2017). In fact, in addition to its traditional role as bona fide transcription factor promoting lymphatic development via enhancing lymphatic gene transcription, PROX1 is a “smart” transcription factor, as it “hijacks” (fatty acid) metabolism to generate a metabolite (acetyl‐CoA), which is then used for epigenetic modification of lymphatic genes via histone acetylation to increase the accessibility of PROX1 to its target genes, thereby further enhancing its transcriptional activity (Fig 1C). Whether there is a similar role to support histone acetylation in vascular ECs remains to be determined.

Pharmacological inhibition of FA synthesis in LECs has also been shown to reduce migration and promote apoptosis (Bastos et al, 2017), although additional mechanistic insight and verification with genetic models are required.

Hypoxia signalling in endothelial cells

Hypoxia and HIF signalling regulate multiple aspects of EC biology, including cell survival and growth, cell invasion and glucose metabolism, overall, contributing to an induction in angiogenesis. Dysregulation of these pathways is frequently observed in disease settings such as cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD), which will be the focus of the coming sections. While the effect of hypoxia on cancer cell metabolism has received increasing attention (Box 1), the role of hypoxia and HIFs in EC metabolism remains poorly studied. Here, we will first briefly describe general effects of hypoxia on EC function. We will then elaborate on the convergence of hypoxia and metabolic signalling in TECs, followed by how hypoxic signalling affects tumour angiogenesis. We also provide perspectives for studying endothelial metabolism in cardiovascular disease (CVD; Box 2).

Box 1:Metabolic response of cancer cells to hypoxia.

Restricted and intermittent blood supply in tumour tissue results in periodical oxygen shortage and reoxygenation, leading to oxidative stress and hypoxia in the tumour microenvironment. Tumour hypoxia, HIF stabilization and lactate accumulation in turn have been associated with worsened disease outcome for tumours (Hirschhaeuser et al, 2011), making hypoxia a hallmark of cancer (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011). Notably, HIF stabilization can also occur in response to genetic alterations (reviewed in Semenza, 2010). Rather than providing a complete historical overview, we provide here a brief summary of some recent key insights in cancer cell metabolism in hypoxia, which have been studied in more detail in cancer cells, but deserve further attention in ECs (Box 1 Figure).

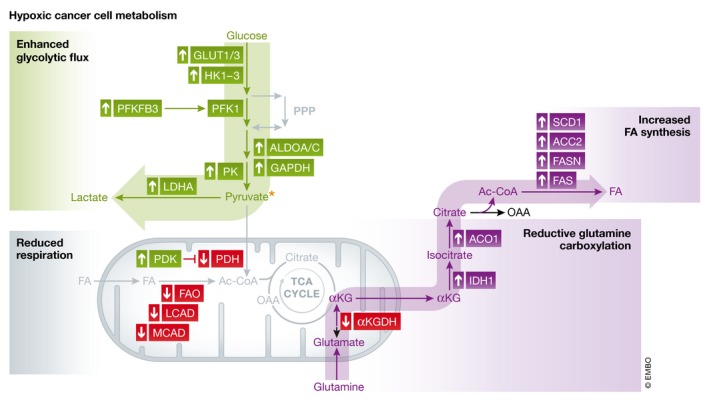

Box 1 Figure.

Hypoxic cancer cell metabolism In hypoxia, cancer cells are characterized by particular changes in their basal metabolism. While many cancer cells are intrinsically glycolytic (characterized by the Warburg effect), in hypoxia, they upregulate glycolysis‐promoting genes including glucose transporters GLUT1/3, hexokinases (HK1‐3), 6‐phosphofructokinase/2,6‐bisphosphatase 3 [PFKFB3; activating the glycolysis rate‐limiting enzyme phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1)], aldolase A/C (ALDOA/C), glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and pyruvate kinase (PK). These facilitate the production of high levels of the glycolytic end‐product pyruvate, which is converted to lactate via lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), also upregulated by hypoxia. HIF1α stabilization also promotes pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) expression, which downregulates pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), the enzyme directing pyruvate to the TCA cycle. Hypoxia decreases fatty acid oxidation (FAO) by lowering medium‐ and long‐chain acetyl‐CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD; LCAD), while fatty acid (FA) synthesis is boosted in cancer cells. This phenomenon involves upregulation of FA synthase (FASN), stearoyl‐CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) and activating acetyl‐CoA carboxylase 2 (ACC2). Hypoxic cancer cells undergo inhibition of glutamine oxidation by α‐ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (αKGDH), which divert glutamine to reductive glutamine carboxylation, thereby producing citrate by upregulating isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and aconitase 1 (ACO1). Altogether, these all contribute to increased glycolytic flux, reductive glutamine carboxylation and FA synthesis, while downregulating respiration in hypoxic cancer cells. Ac‐CoA, acetyl‐CoA; FASN, fatty acid synthase; FAS, fatty acid synthesis; OAA, oxaloacetate.

Hypoxia promotes glycolysis: Stabilization of HIF1α results in a switch from oxidative phosphorylation towards glycolysis (Seagroves et al, 2001), by upregulating glycolysis‐promoting genes, including glucose transporters (GLUT)1 and GLUT3, glycolytic enzymes such as hexokinase (HK) 1, HK3, aldolase A and C and glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase, lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) (Schofield & Ratcliffe, 2004) (Box 1 Figure). PDK1 phosphorylates and thereby inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which mediates the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl‐CoA and subsequent entry into the TCA cycle (Kim et al, 2006) (Box 1 Figure). LDHA in turn promotes the conversion of pyruvate to lactate, using glycolysis‐derived NADH, again directing pyruvate away from the TCA cycle (Semenza et al, 1996). As a result, glucose oxidation is limited, shifting the source of acetyl‐CoA generation to other substrates in hypoxia (see below). Catabolism of NADH to NAD+ in this reaction is essential, as NAD+ levels are required for sustaining glycolysis. In addition, PHD3, which is upregulated upon hypoxia, binds to pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), thereby co‐activating HIF1α for further amplification of glycolysis and tumour growth (Semenza, 2010; Chen et al, 2011). In conditions of low glucose, cancer cells attempt to evade metabolic crisis and metabolize intracellular glycogen storages. In fact, cancer cells accumulate glycogen during hypoxia (Pescador et al, 2010). In cancers that do not purely rely on glycolysis, such as prostate cancers and oxidative phosphorylation‐dependent B‐cell lymphomas, FAO is the primary metabolic pathway for ATP production and ROS scavenging, particularly in hypoxic conditions (Liu et al, 2010; Caro et al, 2012; Li & Cheng, 2014).

Hypoxia promotes glutamine metabolism: Hypoxic cells or cells with dysfunctional mitochondrial and TCA cycling can increase reductive glutamine flux for cell proliferation and viability (Metallo et al, 2011; Wise et al, 2011; Mullen et al, 2011). Reductive carboxylation of glutamine refers to the production of citrate by the enzymes isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 and 2, and aconitase (ACO) 1 and 2. Mechanistically, inhibition of the mitochondrial enzyme complex α‐ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (αKGDH), responsible for oxidative glutamine metabolism, upon hypoxia and HIF stabilization, was suggested to underlie the switch towards reductive carboxylation in cancer cells (Sun & Denko, 2014) (Box 1 Figure). Indeed, HIF1α stabilization results in SIAH2‐mediated ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of the E1 subunit of the αKGDH complex, and knockdown of SIAH2 and thus removal of this degradation mechanism restore glutamine oxidation and reduce reductive carboxylation and glutamine‐dependent lipid synthesis (Sun & Denko, 2014). However, in normoxic cells with HIF stabilization induced by VHL deficiency, citrate levels and citrate/α‐ketoglutarate ratio seem to determine reductive carboxylation activity (Gameiro et al, 2013). Reductive glutamine carboxylation can ultimately promote the generation of acetyl‐CoA, which can be used for the de novo synthesis of FAs.

Hypoxia and fatty acid metabolism: Cancer cells have an increased need for FAs, which may be either uptaken from extracellular sources or synthesized within the cell (Box 1 Figure) (Ackerman & Simon, 2014). Alterations in FA synthesis, storage, uptake/transport and utilization in hypoxia have been described for numerous cancer types (Beloribi‐Djefaflia et al, 2016). Oncogenic transformations (such as oncogenic Ras) can increase their FA uptake and render cancer cells resistant to stearoyl‐CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) inhibition, a critical enzyme necessary for FA synthesis (Kamphorst et al, 2013). Oncogenic signalling via mTORC1 can activate sterol regulatory element‐binding protein (SREBP)‐mediated activation of FA synthesis through the upregulation of SCD1 and FASN (Ackerman & Simon, 2014). Further, hypoxia and HIF signalling promote many of the lipid metabolism pathways that are dysregulated in cancer (Masson & Ratcliffe, 2014), including increased lipid uptake and the induction of lipid kinases and oxidases, such as sphingosine kinase 1 and 12‐lipoxygenase (Ader et al, 2008; Krishnamoorthy et al, 2010). Indeed, genes in FA synthesis, including FASN, are upregulated in cancers and correlate with worse prognosis in various cancers (Beloribi‐Djefaflia et al, 2016) (Box 1 Figure). In particular, FASN is upregulated in hypoxic cell cultures and co‐localized with hypoxic breast tumour areas in vivo (Furuta et al, 2008). Certain hypoxic cancer cells can also accumulate FAs in lipid droplets upon hypoxia for ATP production and for protection against hypoxia–reoxygenation‐induced oxidant stress (Bensaad et al, 2014).

In general, hypoxia increases the intracellular levels of total FAs, as well as omega‐3 FAs, and mono‐, di‐ and poly‐unsaturated FAs, and loss of HIF1α signalling suppressed their levels, as shown in HIF1α−/− hypoxic cancer cells (Valli et al, 2015). The limitation of unsaturated FAs (through nutrient or oxygen deprivation) can induce programmed cell death, as shown in multiple cancer cell lines and in vivo (Duvel et al, 2010; Young et al, 2013), likely through the requirement of oxygen for the desaturation of lipids by SCD1, required for oleic acid synthesis (Kamphorst et al, 2013). Additionally, there is HIF1‐dependent reduction in acetyl‐CoA carboxylase (ACC1) expression (Valli et al, 2015).

As another metabolic substrate for FA synthesis, acetate has been shown to contribute to acetyl‐CoA synthesis in hypoxic cancer cell lines (Kamphorst et al, 2014), though this may not occur generally. Downregulation of the enzyme responsible for the conversion of acetate to acetyl‐CoA, acetyl‐CoA synthetase 2 (ACSS2), in turn has been associated with advanced tumour stage and worse prognosis in certain cancer types (Bae et al, 2017).

Current evidence points to an overall induction of FA synthesis in tumours (Currie et al, 2013), and hypoxic cancer cells can even increase reductive carboxylation of glutamine to increase FA biosynthesis (Metallo et al, 2011) (Box 1 Figure). In general, hypoxic cancer cells upregulate FA uptake or FA synthesis for membrane synthesis, lipid signalling or as energy source (when oxidized) (Currie et al, 2013). HIF1α can, however, reduce FAO by lowering medium‐ and long‐chain acetyl‐CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD and LCAD) expression (Huang et al, 2014). Reduced FAO promotes tumour progression by lowering the expression of the tumour suppressor PTEN, though the mechanism remains unknown (Huang et al, 2014). Upregulation of PHD3 in hypoxia serves to further repress FAO by binding and activating acetyl‐CoA carboxylase 2 (ACC2), which generates malonyl‐CoA, a repressor of FAO (German et al, 2016). The intricate regulation of FA uptake and metabolism in hypoxia highlights its importance in multiple cancer cell types.

Tumour metabolism is cancer cell‐type‐specific: The diversity of nutrients that cancer cells can use suggests changes in metabolism based on microenvironmental availability. Indeed, lung metastases in a metastatic breast cancer model increase pyruvate carboxylase‐dependent anaplerosis using pyruvate derived from the lung microenvironment as well as the metabolism of intracellular glycolysis, as compared to the primary tumour (Christen et al, 2016). While the effect of tumour oxygenation on metabolite utilization was not studied, the presence or absence of oxygen in metastatic sites is likely to also impact the metabolism of metastatic cancer cells. Also, dependent on the organ of origin of the cancer, tumour metabolism can differ, supporting the idea of environment‐ and availability‐driven metabolic adjustments and evasion in cancer (Elia et al, 2016).

Overall, it would be of great interest to assess whether ECs similarly adapt their metabolism to hypoxia or local microenvironment, as in cancer cells. Intriguingly, however, recent work indicates that ECs metabolically differ from cancer cells and might even have a specific (unique?) metabolic properties, as was shown for the use of FAO for nucleotide synthesis (Schoors et al, 2015). Additionally, as tumour metabolism largely depends on the cancer cell type, in addition to the microenvironment, it would be of interest to investigate whether there is heterogeneity in endothelial metabolism based on organ‐specific ECs.

Box 2:Prospects for studying EC metabolism in cardiovascular disease.

Endothelial cell perturbations, ranging from excessive EC growth to dysfunction, have been implicated in patients with a high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), including atherosclerosis, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke (Matsuzawa et al, 2013; Daiber et al, 2017). Previous reviews overviewed the metabolic perturbations in atherosclerotic and diabetic ECs (Rodrigues et al, 1997; Eelen et al, 2015; de Zeeuw et al, 2015; Pircher et al, 2016); however, EC metabolism in CVD in response to hypoxia has not been extensively studied. Given the recent progress in targeting proliferating EC metabolism in tumour biology, further investigation into EC metabolism in CVD is warranted. Here, we will focus on atherosclerosis and pulmonary hypertension (conditions which can result in ischaemic heart disease and heart failure), for which EC metabolism in response to hypoxia has been described so far, even though only in a limited fashion. Additionally, we will briefly describe alterations in diabetic EC metabolism in response to hypoxia, as diabetes is a major risk factor for macro‐ and microvascular disease. While direct evidence for a role of EC metabolic perturbations is often lacking, circumstantial evidence, gathered from other (patho)‐biological processes, is highly suggestive for a similar role of perturbed EC metabolism in CVD. The next paragraphs are enclosed to prime interest and inspiration for future research.

Atherosclerosis: Perturbations in blood flow are an important initiating factor of EC dysfunction preceding atherogenesis (Rodrigues et al, 1997; Cunningham & Gotlieb, 2005; Suo et al, 2007). Laminar shear stress, which elevates the expression of Krüppel‐like factor 2 (KLF2) in ECs, downregulates glycolytic enzymes, including PFKFB3 (Doddaballapur et al, 2015) (Box 2 Figure). As atherosclerotic neovessels are often exposed to flow turbulence, it is tempting to speculate that these flow perturbations might elevate PFKFB3 levels and thereby contribute to increased plaque neovascularization and EC activation, a hypothesis requiring further validation.

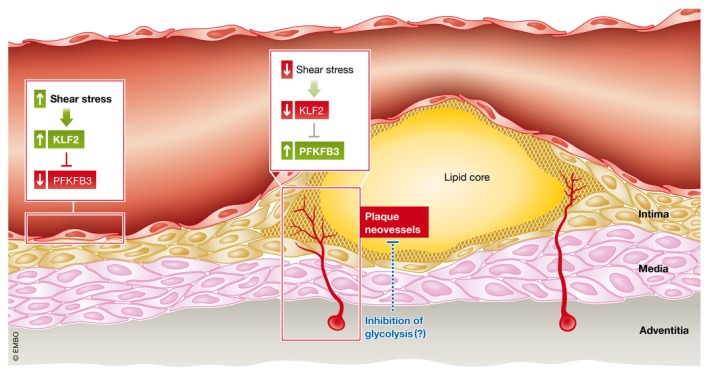

Box 2 Figure.

EC metabolism in atherosclerosis Conditions of high shear stress activate the transcription factor Krüppel‐like factor 2 (KLF2), which serves to repress the expression of the glycolytic regulator 6‐phosphofructokinase/2,6‐bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) in normal, quiescent endothelial cells (ECs), limiting glycolytic flux. In atherosclerosis, alterations to flow in macrovessels, caused by atherosclerotic plaque encroachment into the blood vessel lumen, or in atherosclerotic plaque neovessels, which like tumour vessels, are often leaky and hypoperfused, to the cessation of KLF2‐mediated repression of PFKFB3, thus enhancing glycolytic flux, perturbing macrovascular barrier function and promoting plaque angiogenesis. Limiting glycolysis by targeting PFKFB3 may be a promising therapeutic strategy to limit pathological endothelial alterations in atherosclerosis.

Endothelial cell metabolism in hypoxic atherosclerotic plaques has been challenging to study. While plaque hypoxia increases overall atheroma glucose uptake (Folco et al, 2011), in particular in macrophage‐rich and hypoxic areas, the effect of hypoxia on plaque EC metabolism has not been studied. Overall, EC‐specific HIF1α deficiency reduces atherosclerosis development in apolipoprotein E (apoE)−/− mice (Akhtar et al, 2015). Mechanistically, inflammation and macrophage recruitment via endothelial CXCL1 were reduced, dependent on availability of miR‐19a (Akhtar et al, 2015), suggesting reduced EC dysfunction with respect to vessel wall inflammation influx upon reduction in hypoxic signalling. While EC metabolism was not studied, ECs upregulate glycolysis in response to pro‐inflammatory atherosclerosis‐relevant cytokine stimuli (Folco et al, 2011) and PFKFB3‐driven glycolysis promotes vascular EC inflammation (Cantelmo et al, 2016). It is thus tempting to speculate that inhibition of hypoxia signalling might reduce EC pro‐inflammatory activation in part by reducing EC glycolysis.

Similar to TECs, plaque ECs are exposed to hypoxia and inflammatory cytokines, known to elevate PFKFB3‐driven glycolysis in TECs and atherosclerotic macrophages (Rodrigues et al, 1997; Tawakol et al, 2015; Cantelmo et al, 2016). Further, competition for glucose availability between ECs and macrophages, as occurs in the tumour setting (Wenes et al, 2016), would be of interest to study. Given that plaque vessels are structurally and functionally abnormal (reviewed in Jain et al, 2007) and endothelial PFKFB3 haplodeficiency or pharmacological inhibition normalizes tumour vessels (Cantelmo et al, 2016), it would be interesting to explore whether PFKFB3 blockade might also have anti‐atherosclerotic effects. Also, glycolysis inhibition might improve EC function at the luminal barrier. As HIF induces PFKFB3 expression in hypoxia, the finding that KLF2 can inhibit HIF1α in HUVECs, in vitro (Kawanami et al, 2009), further supports the notion that either directly targeting PFKFB3 or promoting vessel normalization to improve blood flow and shear stress‐mediated KLF2 expression may be promising therapeutic avenue for further investigation (Box 2 Figure).

Pulmonary hypertension: Sustained pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a common complication of chronic lung disease (Howell et al, 2004). In these patients, chronic hypoxia is thought to be a major stimulus of PH development and vascular remodelling of pulmonary arteries and has direct effects on ECs, affecting permeability, coagulation, inflammation and other processes (Stenmark et al, 2006). Next to the originally believed vasoconstriction, excessive angiogenesis upon EC hyperproliferation and suppression of EC apoptosis is now considered to underlie PH (Masri et al, 2007; Duong et al, 2011). Hence, EC function and proliferation in response to hypoxia have recently been studied in pulmonary arterial ECs (PAECs). Indeed, chronic hypoxia induced PAEC proliferation by inducing arachidonate 5‐lipoxygenase metabolites in response to hypoxia‐induced hydrogen peroxide release (Porter et al, 2014). Also, HIF stabilization induced by oxidative stress and low NO levels is observed in PAECs and results in a decrease in the number of mitochondria per cell (Fijalkowska et al, 2010), and also PAECs isolated from idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients (a subgroup of PH) showed reduced oxygen consumption and mitochondrial numbers per cell (Xu et al, 2007). This translated to in vivo, lungs of PAH patients showed greater glucose uptake as measured by FDG‐PET scan compared to controls (Xu et al, 2007). These data suggest that also in PAECs, HIF contributes again to a shift in cellular metabolism away from oxidative phosphorylation towards anaerobic glycolysis, thereby potentially forwarding the EC hyperproliferative phenotype in PH. Targeting glycolysis and normalizing EC proliferation and vessel integrity as shown for PFKFB3 inhibition in tumours (Cantelmo et al, 2016) might thus present an attractive therapy for hypoxia‐induced PH. However, it has been recently demonstrated that both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation are essential for purinergic‐mediated angiogenic responses in vasa vasorum ECs from pulmonary artery adventitia of chronically hypoxic calves (Lapel et al, 2017), suggesting that further study is necessary to determine the role of oxidative EC metabolism in the pathogenesis of PH in vivo.

Interestingly, PAH disease‐causing mutations in the bone morphogenic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2) result in an upregulation of key glycolytic enzymes and GLUT1 in human pulmonary microvascular ECs (PMVECs) with upregulation of the PPP and reduced FAO (Fessel et al, 2012). Though the authors did not study the effect of hypoxia on these cells and PAH has not been mechanistically linked to hypoxia (compared with PH), this metabolic profile seems in line with the hyperproliferative PAEC phenotype, though the significance of the alterations in FAO require further study. Thus, even in BMPR2‐driven PAH, limiting EC glycolysis might prove a useful therapy to prevent EC hyperproliferation and reduce PAH development.

In addition to effects on EC proliferation and in line with the vasoconstriction seen in PH, hypoxia seems to affect vasoconstriction by reducing eNOS function in PAECs (Chalupsky et al, 2015). Vice versa, eNOS function in hypoxic PAECs could be improved upon folate supplementation‐induced dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR)‐mediated regeneration of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) (Chalupsky et al, 2015). In line, statins and oral BH4 supplementation have been shown to reduce PH development by protecting eNOS function in hypoxia‐induced PH in rats and pigs, respectively (Murata et al, 2005; Dikalova et al, 2016). Next to direct metabolic effects of hypoxia in PAECs, metabolite release in PAECs upon hypoxia has also been shown to affect neighbouring cells in PH. In response to ischaemia/oxidative stress, flow and mechanical stretch, vascular cells release ATP as a stress signal (Pearson & Gordon, 1979; Hamada et al, 1998; Graff et al, 2000). PAECs release ATP upon acute hypoxia, which can be utilized by adjacent fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells for migration and proliferation, in an autocrine and paracrine manner (Gerasimovskaya et al, 2002, 2005). Thus, therapies affecting EC metabolism might also beneficially affect metabolism of neighbouring cells, a hypothesis that remains to be validated.

Diabetes: Diabetes is an independent risk factor of several CVDs, including atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction and stroke (Grundy et al, 1999). The ability of hypoxic tissue to improve perfusion in response to an ischaemic event is majorly impaired in diabetes (Howangyin & Silvestre, 2014b). Perturbations of EC metabolism are in part related to hyperglycaemia‐induced ROS and advanced glycosylation end (AGE)‐product formation (Rodrigues et al, 1997; Tan et al, 2002; Mapanga & Essop, 2016), and to other maladaptations (for reviews, see 1999; Sena et al, 2013), including reduced HIF stabilization and response in diabetic tissue (Gunton et al, 2005; Xiao et al, 2013; Howangyin & Silvestre, 2014b). In line with the observation that systemic HIF stabilization by genetically or pharmacologically interfering with PHDs can precondition to ischaemia–reperfusion injury (reviewed in Eltzschig & Eckle, 2011), reduced HIF in diabetes has also been linked to its role as a risk factor for CVD. Indeed, improving HIF stabilization improved post‐ischaemic revascularization in PHD2‐silenced diabetic mice (HoWangYin et al, 2014a). Next to that, systemic HIFα stabilization, in vivo, improves systemic glucose metabolism in PHD2‐hypomorphic diabetic and PHD1‐deficient atherosclerotic mouse models (Rahtu‐Korpela et al, 2014; Marsch et al, 2016). While the underlying mechanisms remain to be established and vascularization was not studied in these models, increased cellular glucose utilization in these models might imply a link between hypoxia signalling and cardiovascular complications in diabetes. Further, PHD2 hypomorphic mice have reduced acetyl‐CoA levels and expression of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis, overall resulting in decreased de novo lipogenesis (Rahtu‐Korpela et al, 2014). These data suggest that reduction in PHD‐isoform signalling, leading to systemic HIF stabilization, may provide protection from diabetes, possibly due to improved tissue glucose consumption and lipid dynamics. In vitro, EC proliferation is impaired upon hyperglycaemia‐mediated reduction in HIF stabilization (Gao et al, 2014), suggesting direct effects of HIF on EC angiogenic capacity. Clearly, the effect of EC‐specific HIF stabilization on revascularization and glucose metabolism in hyperglycaemic environments (and diabetes) remains to be elucidated.

Ischaemic conditions: Conditions such as vessel occlusion or thrombotic events as a consequence of atherosclerosis can cause ischaemic heart disease, also known as myocardial infarction, whereas thrombosis or emboli are the most common causes of ischaemic brain injury also known as stroke. Myocardial infarction (Moran et al, 2014) and stroke (Koton et al, 2013; Chin & Vora, 2014) contribute to a significant socioeconomic burden and have been proposed to become the leading causes of death and disability worldwide by 2020 (Fuster, 2014). Ischaemia results from restriction of blood supply to tissues, limiting oxygen and glucose availability. In particular, ischaemia–reperfusion injury increases ROS production, disrupts NO bioavailability and causes Ca2+ imbalances, leading to endothelial dysfunction and EC apoptosis (Singhal et al, 2010). Excess ROS formation is induced in ECs exposed to prolonged hypoxia or ischaemia–reperfusion injury (Therade‐Matharan et al, 2004, 2005). This excess ROS overwhelms the endogenous scavenging capacity of ECs, and strategies to promote the production/function of ROS scavengers such as NADPH and GSH through enhancing metabolic pathways such as the PPP and FAO may provide protection in this context and warrant further investigation.

Hypoxia‐sensing mechanisms

Tissue hypoxia is sensed by the hypoxia‐inducible factor (HIF)‐prolyl hydroxylase family of enzymes (PHD1‐3). PHDs require oxygen for their enzymatic activity to hydroxylate hypoxia‐inducible factor α (HIFα) subunits, which targets these subunits for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation via von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) factor (Epstein et al, 2001). During hypoxia, PHDs lose their ability to hydroxylate HIF due to their enzymatic dependence on oxygen, and the loss of this degradation mechanism results in the activation of a HIF‐mediated transcriptional programme, which includes the induction of angiogenesis, glucose metabolism, and cancer cell growth, survival, invasion and metastasis (Semenza, 2003b).

HIFα subunits (HIF1‐3α) are a family of basic helix–loop–helix/PAS transcription factors. HIF functions transcriptionally as a heterodimer, composed of HIFα and HIFβ subunits (with all three HIFα homologues sharing the same β‐subunit), which binds to a hypoxia response element (HRE) in the promoter of target genes (Wang et al, 1995). In most cell types, HIF1α is stabilized upon acute hypoxia. HIF2α and HIF3α have a more restricted expression pattern in acute hypoxia and partially share target genes with HIF1α. With respect to the regulation of cellular metabolism, HIF1α is the predominant subunit that induces glycolysis and other metabolic changes (Hu et al, 2003).

Endothelial phenotypes in response to hypoxia

During development, oxygen gradients during tissue/organ growth trigger physiological hypoxia signalling, which is an important cue for blood vessel growth in development (to provide oxygen and nutrients for cellular metabolism), but hypoxia can also be present in certain organs in healthy adults (i.e. intestinal mucosa, kidney, bone marrow) (Giaccia et al, 2004; Simon & Keith, 2008; Semenza, 2012). Such hypoxic niches can harbour stem cells, which have increased glycolysis rates and reduced oxidative metabolism, which in part help to maintain their undifferentiated state (Folmes et al, 2012; Ito & Suda, 2014; Kocabas et al, 2015). The metabolic properties of ECs exposed to these physiological hypoxic microenvironments remain to be determined.

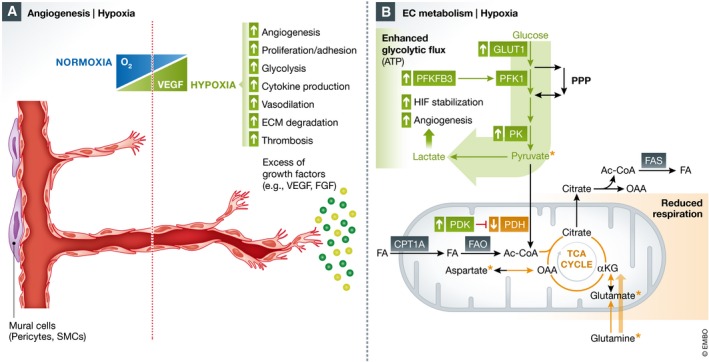

Hypoxia and HIF signalling impact EC function and angiogenesis in multiple ways. On one hand, hypoxia induces transcriptional activation of angiogenic genes [including, e.g. VEGF, placental growth factor (PlGF), platelet‐derived growth factor B (PDGFB), angiopoietins (ANGPT1 and ANGPT2)] (Liu et al, 1995; Semenza, 2003a), but also post‐transcriptionally regulates pro‐angiogenic chemokines and receptors, thus promoting EC progenitor migration to the site of angiogenesis (Ceradini et al, 2004). Of note, angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF, which are further stabilized in hypoxia (Jazwa et al, 2016; Shima et al, 1995), can increase glycolytic flux in ECs (De Bock et al, 2013). Additionally, hypoxia stimulates EC proliferation (Li et al, 2007) and sprouting (Manalo et al, 2005) and promotes vascular remodelling through extracellular matrix remodelling (Faller et al, 1997; Faller, 1999) (Fig 2A). Hypoxia thus regulates EC function and behaviour during the multistep process of angiogenesis.

Figure 2. Oxygen sensing and EC metabolism adaptation to hypoxia.

(A) The hypoxic microenvironment contributes to abnormal sprouting angiogenesis in part via excessive growth factor production (i.e. VEGF, FGF), and oxygen‐responsive genes regulate EC proliferation, glycolysis, cytokine production, thrombosis, prostaglandin synthesis and vasodilation. (B) In hypoxia, HIF signalling upregulates genes involved in glycolysis, including glucose import via GLUT1, PFKFB3 and pyruvate kinase (PK), while downregulating pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), limiting glucose oxidation in the mitochondria. Moreover, lactate production from the increased glycolytic flux can further stabilize HIF and has also been demonstrated to have a direct pro‐angiogenic action on ECs. FA, fatty acid; FAS, fatty acid synthesis; OAA, oxaloacetate; PFK1, phosphofructokinase 1; PDK, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase.

In addition to modulating angiogenesis, hypoxia affects vessel function by increasing vasodilatory responses (Busse et al, 1985; Greenberg & Kishiyama, 1993). In most hypoxic tissues (except for the lungs), hypoxia induces vasodilation to increase blood flow and oxygen/nutrient delivery at the site of hypoxia (Kulandavelu et al, 2015), in part via upregulation of eNOS through binding of HIF to a HRE in the eNOS promoter (Coulet et al, 2003), or via other transcriptional mechanisms (Min et al, 2006), overall resulting in increased NO production/release, promoting vasodilation in vascular smooth muscle cells (Chan & Vanhoutte, 2013).

In a zebrafish model of lymphatic development, hypoxia actually inhibited lymphatic (thoracic duct) formation and inhibited the expression of pro‐lymphangiogenic factors such as PROX1, VEGF‐C and VEGFR3 (Ernens et al, 2017). Profiling of human LECs in hypoxia revealed increased extracellular matrix attachment, decreased proliferation and reduced ROS generation in LECs, increased cancer cell adhesion to LECs in a CXCR4‐dependent manner (Irigoyen et al, 2007). Overall, hypoxia causes dysregulation in lymphangiogenesis, and further investigation is warranted to better understand the alterations that may occur in the context of cancer and CVD.

Endothelial cell metabolism in cancer: influence of hypoxia

The effect of hypoxia on cancer cell metabolism has received increasing attention (Box 1); however, the role of hypoxia and HIFs in EC metabolism remains poorly studied. ECs are often subjected to hypoxic environments in health and disease, for example embryonic development, tissue ischaemia (heart, peripheral limbs upon vessel occlusion), but also tumour development (Carmeliet et al, 1998; Ryan et al, 1998; Jurgensen et al, 2004). In general, a hypoxic environment stimulates EC proliferation and angiogenesis (Carmeliet et al, 1998; Semenza, 2003b). Hypoxia is a characteristic feature in tumour growth, and neovessels within the tumour microenvironment are often exposed to lower oxygen tensions (Brown & Wilson, 2004; Bache et al, 2008). Notably, tumour‐derived ECs have higher rates of glycolysis than normal ECs in healthy tissues (Cantelmo et al, 2016), likely due to a combination of hypoxia‐dependent modifications in the expression of glycolytic enzymes, as well as the secretion of pro‐angiogenic/pro‐glycolytic growth factors such as VEGF. The levels of VEGF secreted in pathological conditions exceed levels produced during physiological states of hypoxia (Matsuyama et al, 2000; Li et al, 2004), and these excessive levels of VEGF have been shown to cause abnormal EC behaviour, perturbing cell rearrangement, which can be normalized by targeting PFKFB3 (Cruys et al, 2016). Also, pro‐inflammatory cytokines present in the tumour microenvironment can upregulate glycolysis in ECs (Cantelmo et al, 2016).

When studying metabolic gene expression in ECs in response to acute hypoxia, alternative splicing and upregulation of genes involved in pyruvate metabolism and glucose transport have been identified (Weigand et al, 2012), supporting the increased rates of glycolysis seen in hypoxic ECs. ECs also upregulate PFKFB3 upon exposure to hypoxia (Xu et al, 2014), potentially via HIF stabilization, as observed in human hepatoma and retinal pigment epithelial cell lines (Minchenko et al, 2002) (Fig 2B), further enhancing the effect of hypoxia on EC proliferation and angiogenesis observed (Carmeliet et al, 1998; Semenza, 2003b). In line, metabolic pathway analysis of ECs exposed to chronic hypoxia revealed increased activity of glycolysis, biosynthesis of amino acids, carbon metabolism, PPP, fructose/mannose and cysteine/methionine metabolism, effects which could be restored to basal levels by silencing HIF2α (Nauta et al, 2017). However, chronic hypoxia in ECs may not resemble the intermittent hypoxia conditions used to study hypoxic responses in tumours and other tissues. Thus, metabolic changes observed upon chronic hypoxia need to be confirmed in settings of alternating oxygen concentration.

In addition to direct effects of hypoxia on ECs, cancer cell hypoxia can signal to ECs to alter their metabolism. Lactate accumulation in the (hypoxic) tumour environment can result in lactate uptake by ECs, with subsequent conversion to pyruvate for further oxidation (Fig 3). Additionally, lactate uptake by ECs induces a ROS‐mediated NF‐κB and interleukin (IL)‐8 induction (Vegran et al, 2011). Moreover, in MCF‐7 cells, lactate has also been reported to directly modulate receptor tyrosine kinases (including VEGFR2) in ECs, promoting angiogenesis (Ruan & Kazlauskas, 2013), and can also protect N‐Myc downstream‐regulated gene 3 (NDRG3) protein, a putative tumour suppressor, from PHD2/VHL‐dependent degradation in hypoxia, which in turn promoted angiogenesis during hypoxia (Lee et al, 2015). In line with this observation, NDRG3 depletion in HUVECs reduced tube formation (Lee et al, 2015), suggesting lactate can independently act as a pro‐angiogenic stimulus.

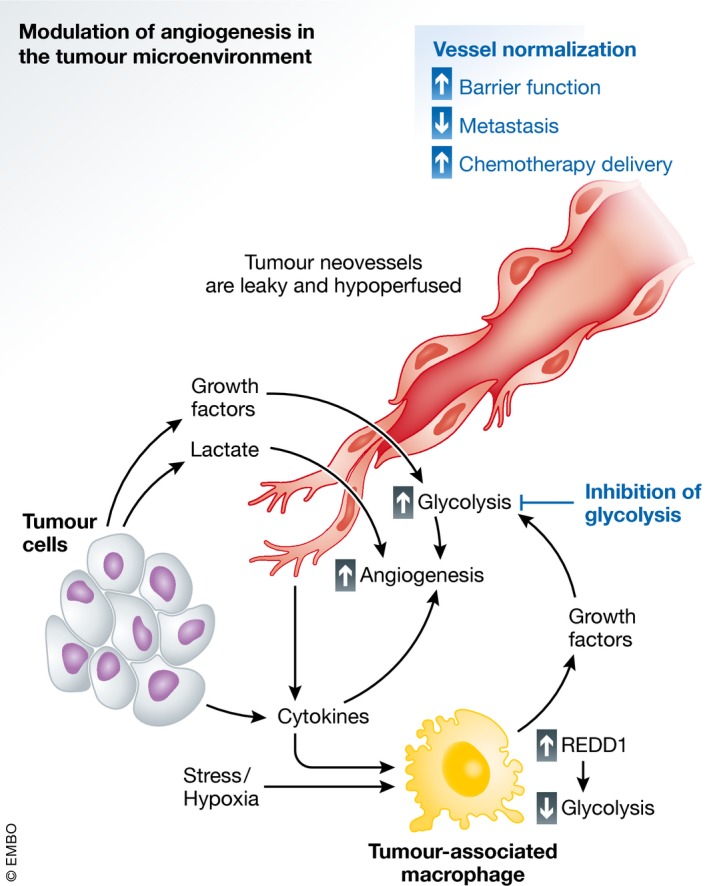

Figure 3. Modulation of angiogenesis in the tumour microenvironment.

Endothelial cells play a central role in the microenvironment in disease and can be modulated by parenchymal and immune cells. In the tumour setting, the hypoxic microenvironment stimulates cancer cells to produce growth factors, cytokines and lactate. The same holds true for tumour‐associated macrophages (TAMs), which release high levels of pro‐angiogenic factors in response to the extracellular milieu and cancer cells. Moreover, in TAMs, tumour‐derived cytokines and hypoxia induce the expression of “regulated in development and DNA damage response 1” (REDD1) which reduces TAM glycolysis, therefore saving more glucose access for tumour ECs (TECs). These all contribute to increased angiogenesis in TECs, which are characterized by increased glycolytic flux, and result in vessels that are leaky and hypoperfused, due in part to pathological levels of VEGF. Limiting glycolysis in TECs can revert these changes, resulting in normalized vessels characterized by improved barrier function, limiting tumour cell metastasis and improving chemotherapeutic delivery.

Another example of tumour microenvironment‐mediated modulation of EC metabolism is highlighted by a recent report of crosstalk between tumour‐associated macrophage (TAM) glycolysis and EC function (Wenes et al, 2016). Hypoxia upregulates the expression of the “regulated in development and DNA damage response 1” (REDD1) gene, an inhibitor of mTOR activation. In a REDD1 knockout mouse model, where glycolysis in tumour‐associated macrophages (TAMs) is enhanced in a mTOR‐dependent manner, competition for extracellular glucose between macrophages and TECs results in a reduction in glycolytic flux in ECs (Wenes et al, 2016). This promoted a more quiescent EC phenotype with continuous VE‐cadherin junctions (Wenes et al, 2016), overall resulting in tumour vessel normalization (Fig 3). Hypoxia in ECs can also impact macrophage behaviour and recruitment, as EC‐specific HIF1α deficiency reduces CXCL1‐mediated macrophage recruitment, further altering the dynamics of the interaction between macrophages and ECs in the tumour microenvironment (Akhtar et al, 2015) (Fig 3). Interestingly, alterations in cellular metabolism can also impact pro‐inflammatory anti‐tumoural macrophages (so‐called M1‐like) versus the M2‐like immunosuppressive, pro‐tumoural and pro‐angiogenic macrophages (O'Neill & Pearce, 2016b; O'Neill et al, 2016a). Indeed, activation of M1‐like macrophages by LPS leads to a stalled TCA cycle, and an increase in glycolysis, while M2‐like macrophages display intact TCA cycle, with reliance on oxidative phosphorylation (Tannahill et al, 2013; Galvan‐Pena & O'Neill, 2014; Jha et al, 2015). Succinate accumulation in M1‐like macrophages further sustains hypoxia‐driven effects by stabilizing HIF1α via the inhibition of PHDs, increasing HIF‐responsive genes including the pro‐angiogenic/pro‐glycolytic VEGF, and pro‐inflammatory cytokines (i.e. IL‐1β) that can also increase glycolysis in ECs (Infantino et al, 2011; Tannahill et al, 2013; Cantelmo et al, 2016). Further, citrate accumulation induces the release of pro‐inflammatory molecules such as ROS, NO and prostaglandins.

Hypoxic signalling in ECs: effect on tumour angiogenesis

Hypoxia in ECs has been primarily studied through targeting of PHD‐ and/or HIF‐mediated signalling. EC‐specific HIF1α stabilization promotes EC migration and proliferation in vitro and in vivo (Tang et al, 2004; Takeda & Fong, 2007). The induction of angiogenesis by hypoxia and HIF is largely VEGF dependent. HIF directly induces VEGF in ECs (Manalo et al, 2005) (and other cells), and in turn, VEGF acts as the primary regulator of angiogenesis, inducing subsequent activation of other pro‐angiogenic growth factors such as PlGF and fibroblast growth factor (Forsythe et al, 1996). Thereby, HIF both directly and indirectly promotes angiogenesis (Li et al, 2002).

Indeed, endothelial HIF1α deficiency in vivo decreased the number of tumour vessels, which reduced tumour growth and enhanced tumour necrosis as a consequence of lack of nutrient and oxygen delivery to the tumour core (Tang et al, 2004). Similar effects were seen for endothelial HIF2α deficiency, which reduced vessel integrity in ischaemia/reperfusion and tumour models (Skuli et al, 2009, 2012; Gong et al, 2015), with a reduction in tumour growth (Skuli et al, 2009). In contrast, PHD2 haplodeficiency mediates HIF2α stabilization in ECs, which normalizes TECs, reverting tumour hypoxia and reducing cancer cell metastasis (Mazzone et al, 2009). Thus, HIF1α stabilization and HIF2α stabilization seem to differentially regulate vessel growth and vessel integrity/normalization. Tumour vessels are functionally and structurally perturbed, which impairs perfusion, thereby creating a nutrient/oxygen‐deprived hostile milieu, from which cancer cells attempt to escape and metastasize to other sites in the body (Carmeliet & Jain, 2011) (see more below). In addition, impaired tumour perfusion also impedes the delivery of chemo‐ and immunotherapeutics (Carmeliet & Jain, 2011; Cantelmo et al, 2016). Thus, while on the one hand, inhibition of hypoxic signalling and mainly HIF1α in ECs prunes tumour vessels and reduces tumour growth (but increases tumour necrosis), targeted stimulation of hypoxic signalling via HIF2α in ECs improves tumour oxygenation and limits tumour growth via tumour vessel normalization. This has led to the paradigm shift that tumour vessel normalization [which also improves therapeutic responses to chemo‐ and radiation therapy (Carmeliet & Jain, 2011)] might represent a therapeutic alternative (or complementation) to anti‐angiogenic strategies resulting in vessel pruning.

As an important confirmation of the contextual role and importance of hypoxia signalling in ECs, in spontaneously arising and metastasizing tumour models, both EC‐specific PHD2 haplodeficiency and cancer cell‐specific PHD2 haplodeficiency improve tumour vessel normalization via HIF2α stabilization but also decrease cancer‐associated fibroblast activation and metastasis formation (Mazzone et al, 2009; Leite de Oliveira et al, 2012; Kuchnio et al, 2015), making malignant and stromal PHD2 blockade a promising strategy in oncotherapy. Further, EC‐specific PHD2 deficiency HIF‐dependently normalizes tumour vessels and increases chemotherapy delivery to the tumour (Leite de Oliveira et al, 2012), supportive of further development of (EC‐specific) PHD2 interventions in cancer.

Nonetheless, despite these convincing genetic data in spontaneously developing mouse models, it would be wise to keep in mind that hypoxia signalling has been reported to induce contextual effects, depending on the tumour model and type, the method and cell type of targeting, etc., and PHDs can have HIF‐independent effects. For instance, PHD2 interference in cancer cells reduced tumour vessel growth in experimental tumour models in a HIF‐independent manner (Chan et al, 2009; Klotzsche‐von Ameln et al, 2011). Overall, PHD2 inhibition shows HIF‐dependent and HIF‐independent effects on tumour growth, depending on tumour type and site of interference. Interestingly, tumour EC HIF1α and HIF2α also differentially affected metastasis formation. While HIF1α interference reduced NO synthesis, cancer cell migration and metastasis, loss of HIF2α resulted in the opposite phenotype in a mouse model of mammary cancer (Branco‐Price et al, 2012).

Translational implications

The original paradigm for anti‐angiogenic therapies was based upon the blockade of tumour vascular supply (i.e. by blocking VEGF), to “starve” the tumour of nutrients and oxygen necessary for growth (Folkman, 1971). However, work over the past decades has revealed that escape mechanisms in tumours ensure tumour angiogenesis, in part through expression of alternative angiogenic factors (i.e. growth factors, cytokines), in response to targeted anti‐growth factor therapies. Furthermore, pronounced inhibition of tumour angiogenesis can increase tumour hypoxia, reducing radio‐ and chemotherapy delivery/sensitivity (Jain, 2014). An emerging alternative is to focus on vessel normalization rather than destruction.

As mentioned briefly above, tumour vessels are structurally and functionally highly abnormal and disorganized, resulting in impaired—rather than improved—tumour perfusion and oxygenation, and reduced delivery and response to chemo‐ and immunotherapy (Cantelmo et al, 2016). This creates a hostile milieu, deprived of oxygen and nutrients, from where cancer cells attempt to escape. In addition, tumour vessels are leaky with dysfunctional junctions and immature because pericytes become detached, all facilitating cancer cell intravasation and dissemination (Cantelmo et al, 2016). Initial studies documented that PHD2 targeting promoted tumour vessel normalization (see above). As an extension of these observations, recent findings indicate that endothelial PFKFB3 haplodeficiency improves tumour vessel normalization, thereby reducing cancer cell invasion and metastasis in murine metastasis models (Cantelmo et al, 2016). Mechanistically, lowering PFKFB3‐driven glycolysis in TECs reduces the (glycolytic) ATP‐consuming endocytosis process and turnover of VE‐cadherin, thereby stabilizing VE‐cadherin‐positive adherens junctions and tightening the endothelial barrier in tumour vessels, and impairing cancer cell intravasation and metastasis (Cantelmo et al, 2016; Cruys et al, 2016). In addition, decreasing tumour EC glycolysis reduces NF‐κB‐dependent vascular inflammation, thereby impairing cancer cell adhesion to and transmigration through ECs (Cantelmo et al, 2016). Furthermore, using a pharmacological inhibitor of PFKFB3 inhibitor (3PO) also improved pericyte coverage of vessels via lowering of glycolysis in pericytes, promoting quiescence (Cantelmo et al, 2016). In line with this, treatment with 3PO increased chemotherapy delivery to tumours, improving efficacy of standard dose chemotherapy regimens. As mentioned above, mTOR activation in hypoxic TAMs has been shown to reduce glucose availability to ECs, another mechanism of promoting tumour vessel normalization (Wenes et al, 2016) (Fig 3). Recently, the study of cellular metabolism in immune cells, termed “immunometabolism”, has emerged, and studies have demonstrated the central role of metabolic changes in immune cell activation and functions (reviewed in O'Neill et al, 2016a; O'Neill & Pearce, 2016b), providing a striking parallel between immune and EC metabolism. Indeed, glycolysis and fatty acid synthesis are signatures of certain T‐cell subsets (T helper) (Michalek et al, 2011), while truncation of the TCA cycle is characteristic in M1‐like macrophages (see above, Tannahill et al, 2013) and PPP flux is required for their polarization (Haschemi et al, 2012). In activated effector CD8+ T cells, an increase in glycolysis is required to sustain sufficient ATP levels for immune cells to fulfil their effector functions (Shi et al, 2011). As it is the case in tip versus phalanx cells in ECs, the metabolic pathways utilized by activated T cells and M1‐like versus M2‐like macrophages (different “activated” or polarized states of macrophages) are dynamically altered (see above). Together, these studies highlight the impact of stromal and immune cells, which can modulate EC function in a disease context (Ghesquiere et al, 2014).

In cancer cells, PFKFB3 inhibition decreases glucose uptake and proliferation (Clem et al, 2008; O'Neal et al, 2016). Also, PFKFB3 inhibition, in concert with HIF1α stabilization, has been described to reduce glycolytic flux and pro‐inflammatory activation in macrophages (Tawakol et al, 2015) and T cells (Telang et al, 2012). PFKFB3 inhibition could thus have beneficial effects on both cancer cells and other stromal cells in the tumour microenvironment, overall hampering tumour progression. As a note of caution, anti‐tumour effects of glycolysis inhibition can be counteracted by survival pathways in cancer cells, in part through ATP depletion. Along these lines, PFKFB3 induces cell cycle progression and suppresses apoptosis in a Cdk1‐dependent manner in cancer cells (Yalcin et al, 2014), while PFKFB3 inhibition induces autophagy as a survival mechanism in cancer cells (Klarer et al, 2014). As ECs are much more sensitive to PFKFB3 blockade than cancer cells (Clem et al, 2008; Cantelmo et al, 2016), additional investigation is required to optimally translate this preclinical observation to a safe and efficacious therapeutic implementation in the clinic.

Our knowledge and understanding of the biology of EC metabolism are rapidly expanding, and recent publications have highlighted the efficacy of targeting EC metabolism in the context of pathological and tumour angiogenesis (De Bock et al, 2013; Schoors et al, 2014a,b, 2015; Cantelmo et al, 2016; Wenes et al, 2016) and broaden these findings into the investigation of CVD yields great translational prospect. As well, as hypoxia signalling in ECs modulates major metabolic pathways (i.e. glycolysis) and is intimately involved in pathological angiogenesis, targeted studies investigating how hypoxia in physiological and pathological contacts modulates EC metabolism and function are of high priority to unlock the potential of EC metabolism‐focused anti‐angiogenic therapeutics.

Author contributions

BWW, EM, LT, MB and PC contributed to the conception, literature review and writing of the topics covered in this review article. BWW made the figures.

Conflict of interest

PC declares to be named as inventor on patent applications, claiming subject matter related to the results described in this paper. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from FWO Postdoctoral Fellowships (BWW; EM) and Marie Skłodowska‐Curie Postdoctoral Fellowships (BWW; LT). Supporting grants, PC: IUAP P7/03, long‐term structural Methusalem funding by the Flemish Government, FWO G.0598.12, G.0532.10, G.0817.11, G.0834.13, 1.5.202.10.N, G0B1116N Krediet aan navorsers, Leducq Transatlantic Network Artemis, AXA Research Fund (1465), Foundation against Cancer, ERC Advanced Research Grant (EU‐ERC269073, PC).

The EMBO Journal (2017) 36: 2187–2203

References

- (1999) Diabetes mellitus: a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. A joint editorial statement by the American Diabetes Association; The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; The Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International; The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; and The American Heart Association. Circulation 100: 1132–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman D, Simon MC (2014) Hypoxia, lipids, and cancer: surviving the harsh tumor microenvironment. Trends Cell Biol 24: 472–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ader I, Brizuela L, Bouquerel P, Malavaud B, Cuvillier O (2008) Sphingosine kinase 1: a new modulator of hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha during hypoxia in human cancer cells. Cancer Res 68: 8635–8642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar S, Hartmann P, Karshovska E, Rinderknecht FA, Subramanian P, Gremse F, Grommes J, Jacobs M, Kiessling F, Weber C, Steffens S, Schober A (2015) Endothelial hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1alpha promotes atherosclerosis and monocyte recruitment by upregulating microRNA‐19a. Hypertension 66: 1220–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alitalo K (2011) The lymphatic vasculature in disease. Nat Med 17: 1371–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bache M, Kappler M, Said HM, Staab A, Vordermark D (2008) Detection and specific targeting of hypoxic regions within solid tumors: current preclinical and clinical strategies. Curr Med Chem 15: 322–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae JM, Kim JH, Oh HJ, Park HE, Lee TH, Cho NY, Kang GH (2017) Downregulation of acetyl‐CoA synthetase 2 is a metabolic hallmark of tumor progression and aggressiveness in colorectal carcinoma. Mod Pathol 30: 267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos DC, Paupert J, Maillard C, Seguin F, Carvalho MA, Agostini M, Coletta RD, Noel A, Graner E (2017) Effects of fatty acid synthase inhibitors on lymphatic vessels: an in vitro and in vivo study in a melanoma model. Lab Invest 97: 194–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloribi‐Djefaflia S, Vasseur S, Guillaumond F (2016) Lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Oncogenesis 5: e189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensaad K, Favaro E, Lewis CA, Peck B, Lord S, Collins JM, Pinnick KE, Wigfield S, Buffa FM, Li JL, Zhang Q, Wakelam MJ, Karpe F, Schulze A, Harris AL (2014) Fatty acid uptake and lipid storage induced by HIF‐1alpha contribute to cell growth and survival after hypoxia‐reoxygenation. Cell Rep 9: 349–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco‐Price C, Zhang N, Schnelle M, Evans C, Katschinski DM, Liao D, Ellies L, Johnson RS (2012) Endothelial cell HIF‐1alpha and HIF‐2alpha differentially regulate metastatic success. Cancer Cell 21: 52–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GC, Cooper CE (1994) Nanomolar concentrations of nitric oxide reversibly inhibit synaptosomal respiration by competing with oxygen at cytochrome oxidase. FEBS Lett 356: 295–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Wilson WR (2004) Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 437–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse R, Trogisch G, Bassenge E (1985) The role of endothelium in the control of vascular tone. Basic Res Cardiol 80: 475–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantelmo AR, Conradi LC, Brajic A, Goveia J, Kalucka J, Pircher A, Chaturvedi P, Hol J, Thienpont B, Teuwen LA, Schoors S, Boeckx B, Vriens J, Kuchnio A, Veys K, Cruys B, Finotto L, Treps L, Stav‐Noraas TE, Bifari F et al (2016) Inhibition of the glycolytic activator PFKFB3 in endothelium induces tumor vessel normalization, impairs metastasis, and improves chemotherapy. Cancer Cell 30: 968–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, Fukumura D, Brusselmans K, Dewerchin M, Neeman M, Bono F, Abramovitch R, Maxwell P, Koch CJ, Ratcliffe P, Moons L, Jain RK, Collen D, Keshert E (1998) Role of HIF‐1alpha in hypoxia‐mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature 394: 485–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P (2005) Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 438: 932–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK (2011) Principles and mechanisms of vessel normalization for cancer and other angiogenic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10: 417–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro P, Kishan AU, Norberg E, Stanley IA, Chapuy B, Ficarro SB, Polak K, Tondera D, Gounarides J, Yin H, Zhou F, Green MR, Chen L, Monti S, Marto JA, Shipp MA, Danial NN (2012) Metabolic signatures uncover distinct targets in molecular subsets of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell 22: 547–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, Tepper OM, Bastidas N, Kleinman ME, Capla JM, Galiano RD, Levine JP, Gurtner GC (2004) Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF‐1 induction of SDF‐1. Nat Med 10: 858–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalupsky K, Kracun D, Kanchev I, Bertram K, Gorlach A (2015) Folic acid promotes recycling of tetrahydrobiopterin and protects against hypoxia‐induced pulmonary hypertension by recoupling endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Antioxid Redox Signal 23: 1076–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DA, Kawahara TL, Sutphin PD, Chang HY, Chi JT, Giaccia AJ (2009) Tumor vasculature is regulated by PHD2‐mediated angiogenesis and bone marrow‐derived cell recruitment. Cancer Cell 15: 527–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CK, Vanhoutte PM (2013) Hypoxia, vascular smooth muscles and endothelium. Acta Pharm Sin B 3: 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Rinner O, Czernik D, Nytko KJ, Zheng D, Stiehl DP, Zamboni N, Gstaiger M, Frei C (2011) The oxygen sensor PHD3 limits glycolysis under hypoxia via direct binding to pyruvate kinase. Cell Res 21: 983–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin JH, Vora N (2014) The global burden of neurologic diseases. Neurology 83: 349–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen S, Lorendeau D, Schmieder R, Broekaert D, Metzger K, Veys K, Elia I, Buescher JM, Orth MF, Davidson SM, Grunewald TG, De Bock K, Fendt SM (2016) Breast cancer‐derived lung metastases show increased pyruvate carboxylase‐dependent anaplerosis. Cell Rep 17: 837–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clem B, Telang S, Clem A, Yalcin A, Meier J, Simmons A, Rasku MA, Arumugam S, Dean WL, Eaton J, Lane A, Trent JO, Chesney J (2008) Small‐molecule inhibition of 6‐phosphofructo‐2‐kinase activity suppresses glycolytic flux and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther 7: 110–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi E, Brown GC, Feelisch M, Moncada S (1998) Persistent inhibition of cell respiration by nitric oxide: crucial role of S‐nitrosylation of mitochondrial complex I and protective action of glutathione. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7631–7636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory JG, Cory AH (2006) Critical roles of glutamine as nitrogen donors in purine and pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis: asparaginase treatment in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In Vivo 20: 587–589 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulet F, Nadaud S, Agrapart M, Soubrier F (2003) Identification of hypoxia‐response element in the human endothelial nitric‐oxide synthase gene promoter. J Biol Chem 278: 46230–46240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruys B, Wong BW, Kuchnio A, Verdegem D, Cantelmo AR, Conradi LC, Vandekeere S, Bouche A, Cornelissen I, Vinckier S, Merks RM, Dejana E, Gerhardt H, Dewerchin M, Bentley K, Carmeliet P (2016) Glycolytic regulation of cell rearrangement in angiogenesis. Nat Commun 7: 12240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucullo L, Hossain M, Puvenna V, Marchi N, Janigro D (2011) The role of shear stress in Blood‐Brain Barrier endothelial physiology. BMC Neurosci 12: 40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KS, Gotlieb AI (2005) The role of shear stress in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Lab Invest 85: 9–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie E, Schulze A, Zechner R, Walther TC, Farese RV Jr (2013) Cellular fatty acid metabolism and cancer. Cell Metab 18: 153–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagher Z, Ruderman N, Tornheim K, Ido Y (2001) Acute regulation of fatty acid oxidation and amp‐activated protein kinase in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Circ Res 88: 1276–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiber A, Steven S, Weber A, Shuvaev VV, Muzykantov VR, Laher I, Li H, Lamas S, Munzel T (2017) Targeting vascular (endothelial) dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol 174: 1591–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bock K, Georgiadou M, Schoors S, Kuchnio A, Wong BW, Cantelmo AR, Quaegebeur A, Ghesquiere B, Cauwenberghs S, Eelen G, Phng LK, Betz I, Tembuyser B, Brepoels K, Welti J, Geudens I, Segura I, Cruys B, Bifari F, Decimo I et al (2013) Role of PFKFB3‐driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell 154: 651–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB (2008) The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab 7: 11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalova A, Aschner JL, Kaplowitz MR, Summar M, Fike CD (2016) Tetrahydrobiopterin oral therapy recouples eNOS and ameliorates chronic hypoxia‐induced pulmonary hypertension in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 311: L743–L753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doddaballapur A, Michalik KM, Manavski Y, Lucas T, Houtkooper RH, You X, Chen W, Zeiher AM, Potente M, Dimmeler S, Boon RA (2015) Laminar shear stress inhibits endothelial cell metabolism via KLF2‐mediated repression of PFKFB3. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong HT, Comhair SA, Aldred MA, Mavrakis L, Savasky BM, Erzurum SC, Asosingh K (2011) Pulmonary artery endothelium resident endothelial colony‐forming cells in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ 1: 475–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvel K, Yecies JL, Menon S, Raman P, Lipovsky AI, Souza AL, Triantafellow E, Ma Q, Gorski R, Cleaver S, Vander Heiden MG, MacKeigan JP, Finan PM, Clish CB, Murphy LO, Manning BD (2010) Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol Cell 39: 171–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eelen G, de Zeeuw P, Simons M, Carmeliet P (2015) Endothelial cell metabolism in normal and diseased vasculature. Circ Res 116: 1231–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia I, Schmieder R, Christen S, Fendt SM (2016) Organ‐specific cancer metabolism and its potential for therapy. Handb Exp Pharmacol 233: 321–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig HK, Eckle T (2011) Ischemia and reperfusion–from mechanism to translation. Nat Med 17: 1391–1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O'Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, Tian YM, Masson N, Hamilton DL, Jaakkola P, Barstead R, Hodgkin J, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ (2001) C. elegans EGL‐9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 107: 43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernens I, Lumley AI, Zhang L, Devaux Y, Wagner DR (2017) Hypoxia inhibits lymphatic thoracic duct formation in zebrafish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 482: 1129–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller DV, Weng H, Choi SY (1997) Activation of collagenase IV gene expression and enzymatic activity by the Moloney murine leukemia virus long terminal repeat. Virology 227: 331–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller DV (1999) Endothelial cell responses to hypoxic stress. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 26: 74–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessel JP, Hamid R, Wittmann BM, Robinson LJ, Blackwell T, Tada Y, Tanabe N, Tatsumi K, Hemnes AR, West JD (2012) Metabolomic analysis of bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 mutations in human pulmonary endothelium reveals widespread metabolic reprogramming. Pulm Circ 2: 201–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fijalkowska I, Xu W, Comhair SA, Janocha AJ, Mavrakis LA, Krishnamachary B, Zhen L, Mao T, Richter A, Erzurum SC, Tuder RM (2010) Hypoxia inducible‐factor1alpha regulates the metabolic shift of pulmonary hypertensive endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 176: 1130–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folco EJ, Sheikine Y, Rocha VZ, Christen T, Shvartz E, Sukhova GK, Di Carli MF, Libby P (2011) Hypoxia but not inflammation augments glucose uptake in human macrophages: implications for imaging atherosclerosis with 18fluorine‐labeled 2‐deoxy‐D‐glucose positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J (1971) Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med 285: 1182–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmes CD, Dzeja PP, Nelson TJ, Terzic A (2012) Metabolic plasticity in stem cell homeostasis and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 11: 596–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, Semenza GL (1996) Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia‐inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol 16: 4604–4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta E, Pai SK, Zhan R, Bandyopadhyay S, Watabe M, Mo YY, Hirota S, Hosobe S, Tsukada T, Miura K, Kamada S, Saito K, Iiizumi M, Liu W, Ericsson J, Watabe K (2008) Fatty acid synthase gene is up‐regulated by hypoxia via activation of Akt and sterol regulatory element binding protein‐1. Cancer Res 68: 1003–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster V (2014) Global burden of cardiovascular disease: time to implement feasible strategies and to monitor results. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: 520–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galkin A, Higgs A, Moncada S (2007) Nitric oxide and hypoxia. Essays Biochem 43: 29–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan‐Pena S, O'Neill LA (2014) Metabolic reprograming in macrophage polarization. Front Immunol 5: 420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]