Abstract

Melamine causes renal tubular cell injury through inflammation, fibrosis, and apoptosis. Although melamine affects the rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and proapoptotic pathway activation, the mechanism of upstream Ca2+ signaling is unknown. Because melamine has some structural similarities with l-amino acids, which endogenously activate Ca2+-sensing receptors (CSR), we examined the effect of melamine on CSR-induced Ca2+ signaling and apoptotic cell death. We show here that melamine activates CSR, causing a sustained Ca2+ entry in the renal epithelial cell line, LLC-PK1. Moreover, such CSR stimulation resulted in a rise in [Ca2+]i, leading to enhanced ROS production. Furthermore, melamine-induced elevated [Ca2+]i and ROS production caused a dose-dependent increase in apoptotic (by DAPI staining, DNA laddering, and annexin V assay) and necrotic (propidium iodide staining) cell death. Upon examining the downstream mechanism, we found that transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), which increases extracellular matrix genes and proapoptotic signaling, was also upregulated at lower doses of melamine, which could be due to an early event inducing apoptosis. Additionally, cells exposed to melamine displayed a rise in pERK activation and lactate dehydrogenase release resulting in cytotoxicity. These results offer a novel insight into the molecular mechanisms by which melamine exerts its effect on CSR, causing a sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i, leading to ROS generation, fibronectin production, proapoptotic pathway activation, and renal cell damage. Together, these results thus suggest that melamine-induced apoptosis and/or necrosis may subsequently result in acute kidney injury and promote kidney stone formation.

Keywords: melamine, kidney tubular cells, Ca2+-sensing receptor, intracellular Ca2+, apoptosis, cell cytotoxicity, acute kidney injury, kidney stone

melamine (2,4,6-triamino-1,3,5-triazine) is a versatile compound with many industrial applications and, when combined with formaldehyde, is included in laminates, adhesives, and cleaning materials (16). However, reported occurrences of kidney stones and acute kidney injury (AKI) have been found among children who ingested milk-based infant formula contaminated with melamine, which was used to falsely increase its protein value, thus increasing awareness of the nephrotoxic effects of melamine. Indeed, recent studies have provided evidence that melamine can cause nephrolithiasis, chronic kidney inflammation, and bladder carcinoma (22). Additionally, melamine was found to leak from melamine-lined tableware when in contact with hot foods or acids (30). Recent research has identified several potential pathways of melamine-induced renal cytotoxicity in kidney epithelial cell lines, resulting in increased inflammation and oxidative stress (29), elevated caspase-3 activity (25), and excessive intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (21), leading to apoptosis.

Excess intracellular calcium ion concentration ([Ca2+]i), has been shown to be involved in the modulation of apoptosis (6, 13, 34, 37, 53). For example, caspases, the apoptotic proteolytic cascades, have a demonstrated link to Ca2+ homeostasis; a disruption of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ homeostasis and the subsequent induction of ER stress are also shown to activate caspase-12 (34, 53), which acts downstream on effector caspases, i.e., caspase-3, to induce apoptosis (37). Furthermore, additional evidence has shown an increasing link between Ca2+ release from ER stores by 1,4,5-inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor (IP3R) ER channels and mitochondrial calcium overload, leading to multiple avenues of apoptosis (6). These studies suggest that a sustained increase in [Ca2+]i can induce such proapoptotic pathways and result in renal cell damage. Indeed, disturbances in Ca2+ homeostasis in renal epithelial cells can lead to apoptosis (13). Moreover, studies have demonstrated that increases in [Ca2+]i through Ca2+-signaling mechanisms (intracellular Ca2+ store-induced release and Ca2+ influx) can induce ER stress and caspase activation (11). Accordingly, we explored whether melamine could activate Ca2+ signaling mechanisms at the plasma membrane receptor level to increase [Ca2+]i and induce apoptosis.

Among the plasma membrane receptors, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the major regulator of Ca2+ signaling in different cell types. Calcium-sensing receptor (CSR), a member of subfamily 3 (or C) of GPCR, mediates Ca2+ signaling leading to the activation of G proteins in multiple cell types (9). This stimulates phospholipase Cβ (PLC-β) enzyme to cleave phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into IP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 then binds to IP3R, an ER channel, which subsequently releases Ca2+ from internal ER stores and increases [Ca2+]i (14). The depletion of ER Ca2+ stores and DAG subsequently triggers Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane by directly activating channels such as transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels (24, 28, 46), further elevating [Ca2+]i. We previously demonstrated that extracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]o) signaling in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells forms a functional TRPC-Ca2+ signaling complex (4). We further observe Ca2+ sensing in salivary ductal cells that mediate an allosteric modulation of CSR by l-amino acids such as l-phenylalanine (l-phe) (5). Among the l-amino acid allosteric modulators [such as l-phe and l-tryptophan (l-try)] of CSR, a common amine (NH2) functional group appears to be present (15). Although, the structure-function relationship among these CSR modulators remains to be established, melamine is structurally enriched with such NH2 functional groups and thus encouraged us to explore its effect on the functional activity of CSR. Therefore, the focus of this study was to show whether melamine can activate CSR and induce the rise in [Ca2+]i, which could help us find the mechanism of deleterious events caused by melamine, leading to apoptosis that may subsequently contribute to AKI and kidney stones. Here, we show a functional CSR in LLC-PK1 cells and that melamine can cause a sustained increase in [Ca2+]i, suggesting the prolonged elevation of [Ca2+]i via ER Ca2+ store release and subsequent Ca2+ influx, causing ER stress and apoptosis, which thus may predispose individuals to AKI and kidney stones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Melamine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Melamine stock solution (up to 25 mM) was prepared by dissolving it in deionized H2O at room temperature (25°C). Before application, melamine solution was warmed to 37°C. DMEM, FBS, antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin), and glutamine were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). NPS 2143 hydrochloride and SKF 96365 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluroesceindiacetate (H2DCFDA) was bought from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Thapsigargin and fura-2 AM were obtained from Invitrogen. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) solutions, and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

Cell culture and transfection.

The porcine renal proximal tubule cell line, LLC-PK1, was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). LLC-PK1 cells were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. LLC-PK1 cells were transiently transfected with cDNA and CSR-specific siRNA (siCSR) and a scrambled (control) siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) as described previously (5). We have tested these cells by expression (Western blots and antibody labeling by immunofluorescence) of megalin, a proximal tubule marker protein (data not shown).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

To observe gene expression, LLC-PK1 cells were treated with 1–10 mM melamine for 18 h. Total RNAs were isolated from these cells using TRIzol (Ambion, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as described (3). After extraction, DNAase I (Sigma) treatments were performed, and RNA concentrations were measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (ThemoFisher Scientific). RNA from each sample (1–2 µg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (Promega, Madison, WI). cDNAs were amplified using gene-specific primers of the target genes (Table 1) purchased from Invitrogen and Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) using ready-to-go master mix PCR amplification reagent (Promega). The PCR conditions were as follows (in sequential order): one initial cycle at 95°C for 3 min; 30–35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 45 s; an additional 5 min at 72°C; a final hold at 4°C. The thermal cycler used was a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| Gene | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| TGFβ1 | CTGAGGCTCAAGTTAAAAG | GAACCCGTTAATTTCCAC |

| BCL-2 | AGCGTCAACGGGAGATGTC | GTGATGCAAGCTCCCACCAG |

| BAX-1 | CAGCTCTGAGCAGATCATGAAGACA | GCCCATCTTCTTCCAGATGGTGAGC |

| GAPDH | TCCCTGAGCTGAACGGGAAG | GGAGGAGTGGGTGTCGCTGT |

Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, and confocal imaging.

To examine the localization of CSR in LLC-PK1 cells, polarized monolayers of cells were plated into a 12-mm or 24-mm Costar Transwell polycarbonate cell culture membrane (Martek, Ashland, MA) in DMEM with 10% FBS. Formation of tight junctions and the integrity of the monolayers were determined by serial measurement of transepithelial resistance (TER) at ~130 Ω. The area (cm2) across cell monolayers was measured as previously described to ensure the polarity (4) and then stained with anti-CSR antibody to determine the localization of CSR in these cells. LLC-PK1 cells were harvested by adding ice-cold 1× PBS, pH 7.4 containing 1% (vol/vol) aprotinin (Sigma), which was then immediately solubilized by adding RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors as described previously (31). Protein concentration was determined by using Bio-Rad protein assay (micro assay procedure). Proteins were detected by Western blotting as described previously (5) using anti-CSR (1:400 dilution) and p-ERK (1:1,000 dilution) primary antibodies, the required secondary antibody, and treatment with ThermoScientific Pierce SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrates for Western blot detection. For immunofluorescence detection, cells were rinsed (with 1× PBS; pH 7.4) and then fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (in 1× PBS), pH 7.4 for 30 min. Cells were rinsed again with 1× PBS and treated with 100 mM glycine in PBS for 20 min. Cells were then washed and permeabilized with methanol (80%)/DMSO (20%) at −20°C for 5 min. Following incubation with a blocking solution containing 5% donkey serum and 0.5% BSA in PBS (PBS-BSA) for 20 min, the cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, washed with PBS-BSA, and probed with the required FITC or rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA). The filters (containing the cells) were then excised and mounted onto a slide with antifade reagent (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) for detection of expression. Fluorescence images were taken using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Details of the images are marked in the figure legends.

Time-lapse [Ca2+]i fluorescence measurements.

Ratiometric (340/380) measurements of [Ca2+]i were performed as described previously (4, 5, 31). Fura-2 AM loaded cells were placed on an IX81 motorized inverted microscope equipped with an IX2-UCB control box (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). For time-lapse fluorescence/ratiometric measurements, the IX81 microscope images were fed into a C9100-02 electron multiplier CCD camera with an AC adaptor A3472-07 (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). A Lambda-LS xenon arc lamp and 10-2 optical filter changer (Sutter Instruments Novato, CA) were used as an illuminator capable of light output from 340 and 380 nm to a cutoff of 700 nm. All experiments were conducted in a microincubator, and cells were maintained at 37°C in a gas mixture of 95% air-5% CO2 at all times during the measurement. Ratiometric measurements of [Ca2+]i were obtained using digital microscopy imaging software (SlideBook version 5.0, 3i; Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). Fura-2 AM fluorescence was excited at a wavelength of 500 nm with peak absorbance shifted alternatively at wavelengths of 340 nm and 380 nm as described (4, 5, 31). Cells were brought into focus using a differential interference contrast (DIC) channel. Time lapse was set at 200–500 time points and 1-s intervals to measure 50–150 cells selected as regions of interest (background fluorescence automatically subtracted before 340/380 ratio calculation and graphing). Analysis was performed offline using SlideBook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations).

Electrophysiology.

Whole cell patch-clamp technique was employed to measure ion currents from single cells as described previously (3, 31). Cells were bathed in a solution containing the following (in mM): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 d-glucose monohydrate, and 10 HEPES (NaOH, pH 7.4). Intracellular solution contained the following (in mM): 50 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 60 CsF, 20 EGTA, and10 HEPES (CsOH, pH 7.2). Whole cell recordings were performed with EPC-10 digitally controlled amplifier and Patchmaster software (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Current-voltage (I/V) relationships were measured every 3 s by applying voltage ramps (300 ms) from −100 mV to +100 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. Data were acquired at 5.000 kHz and filtered with 2.873 kHz. After establishment of the whole cell configuration, the series resistance was >500 MW. All experiments were done at a constant room temperature (25°C).

Detection of ROS.

LLC-PK1 cells were treated with melamine (0.3–10.0 mM) in a serum-free medium for 18 h. H2O2 (100 µM) was used a positive control. NPS 2143 and SKF 96365 concentrations used were 10 nM and 100 nM, respectively. At the end of the treatment, ROS were measured using a cell-permeable fluorescent probe H2DCFDA (43). Briefly, cells were incubated with H2DCFDA (10 µM) final concentration in colorless HBSS (Invitrogen) medium for 30 min at 37°C in dark conditions. Afterward, the media were removed, and the cells were washed with 1× PBS and analyzed under a Zeiss LSM710 laser-scan fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss).

DAPI staining.

Apoptotic nuclei were detected using DAPI (Sigma) staining of melamine-treated cells (44). Cell culture and treatment followed the same procedure as described earlier. After treatment with melamine and other stimuli, cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.01% Triton X-100 in 0.1% BSA for 2 min, washed with 1× PBS once, and incubated with DAPI (1 μg/ml in 1× PBS pH 7.4) in 500 µl for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. After staining, the DAPI solution was removed; cells were washed two to three times with 1× PBS and visualized under fluorescence microscopy (Axiovision, Carl Zeiss).

DNA laddering.

The internucleosomal DNA fragmentations in melamine-treated LLC-PK1 cells (19) were examined using the Quick Apoptotic DNA Ladder Detection Kit (Invitrogen). Briefly after treatment, LLC-PK1 cells (5–10 × 105) were harvested and centrifuged at 2,000 g for 5 min. The pelleted cells were then washed with ice-cold 1× PBS and treated with cell lysis buffer and other reagents provided in the kit. DNA was precipitated using 100% ethanol, which was then air dried and suspended in elution buffer supplied by the detection kit. To enhance the solubility, samples were incubated at 37°C for 10 min. The DNA samples were loaded onto a 1% agarose gel containing 0.5 µg/ml ethidium bromide and were run with 0.5× TBE running buffer. The DNA was visualized by a UV transilluminator, and the images were captured with a camera system (Fluor Chem TM 8800; Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Annexin V/PI staining for apoptosis necrosis assay.

Cell culture and treatments have been described in earlier sections. Apoptotic and necrotic cells were detected with the Alexa Fluor 488 annexin V/Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) (45). After treatment, cells were washed with 1× binding buffer, which was supplied by the kit, and incubated with annexin V/PI for 15 min at room temperature according to the protocol described by the manufacturer. Thereafter, cells were washed with 1× binding buffer twice and were analyzed using a Zeiss LSM710 laser-scan fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Lactate dehydrogenase release measurements.

Melamine-induced cell cytotoxicity was determined by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from cells into the culture media (56) using a Cytotoxicity Assay Kit, CytoTox-ONE (Promega). Briefly, cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 as indicated in the kit manual. The cultured media were collected, and 50 µl was added in each well of a 96-well plate. The reaction mixture (50 μl/well) was then added and incubated without exposure to light for 60 min at room temperature. The fluorescence was measured with an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm using a SpectraMax M5e Multimode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Data were compiled using SoftMax Pro Software, version 5.4 (Molecular Devices). Cytotoxicity was determined by subtracting the value obtained with media and reagent only.

Statistical analysis.

Experimental data were plotted, and curve-fitting was performed using Origin 6.1. The data were expressed routinely as means ± SE. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student’s unpaired t-test (two-tailed) or ANOVA as appropriate, in Origin 6.1. Statistically significant comparisons were accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Melamine-induced Ca2+ signaling in LLC-PK1 cells.

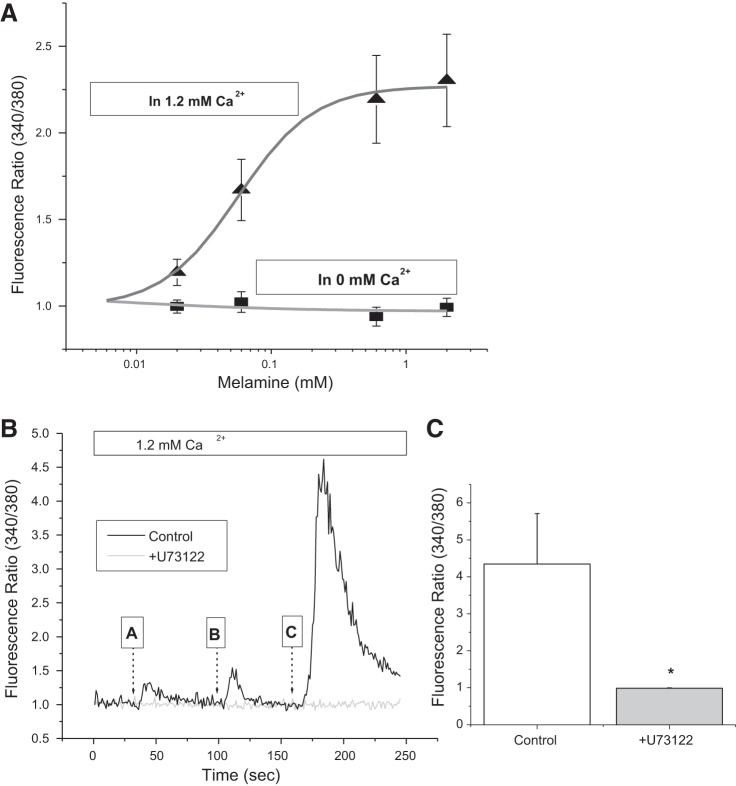

To delineate the mechanism of melamine-induced Ca2+ signaling, we have used LLC-PK1 cells, a cell line derived from pig kidneys, which exhibit features of kidney proximal tubular epithelia (8). The concentrations of melamine used in this study are based on several in vitro and in vivo preclinical and clinical studies justifying the amount of caused oxidative stress-induced cell death and stone-forming features (21, 25, 26, 50). Our experiments using melamine with a [Ca2+]o free media on these cells failed to produce any effect; however, they did induce a rise in [Ca2+]i that was dependent on the prevailing [Ca2+]o (Fig. 1A), similar to activation by CSR (42). Interestingly, melamine mobilizes [Ca2+]i (as indicated by the peak fluorescence ratios of increasing melamine concentrations in Fig. 1A) at near physiological [Ca2+]o (1.2 mM). A concentration-dependent effect of melamine in [Ca2+]i rise was nearly abolished by a PLC inhibitor, U73122 (33), and thus confirms the GPCR involvement (Fig. 1, B and C). The inhibition of [Ca2+]i increase indicates the contribution of the PLC pathway, inducing ER release of internal Ca2+ stores after GPCR activation.

Fig. 1.

Melamine activates Ca2+ mobilization in LLC-PK1 cells. A: concentration-dependent [Ca2+]i rise by melamine (0.03 mM, 0.10 mM, 0.30 mM, and 3.00 mM) in Ca2+-free (gray trace) and 1.2 mM Ca2+ (black trace) media. Mean fluorescence traces of fura-2 AM-loaded LLC-PK1 cells were bathed in 1.2 mM Ca2+ media showing changes in the fluorescence ratio (340/380 excitation). B: with the application of increasing doses of melamine [(in mM) 0.5 at 30s, 2.0 at 100 s, 3.0 at 160 s] incubated with phospholipase (PLC) inhibitor, U73122 (gray trace), and without (control, black trace). C: peak fluorescence ratio values after 3 mM melamine application, without any inhibitor (control, open bar) and incubated in PLC inhibitor, U73122 (shaded bar). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

[Ca2+]o-dependent effect of melamine in LLC-PK1 cells.

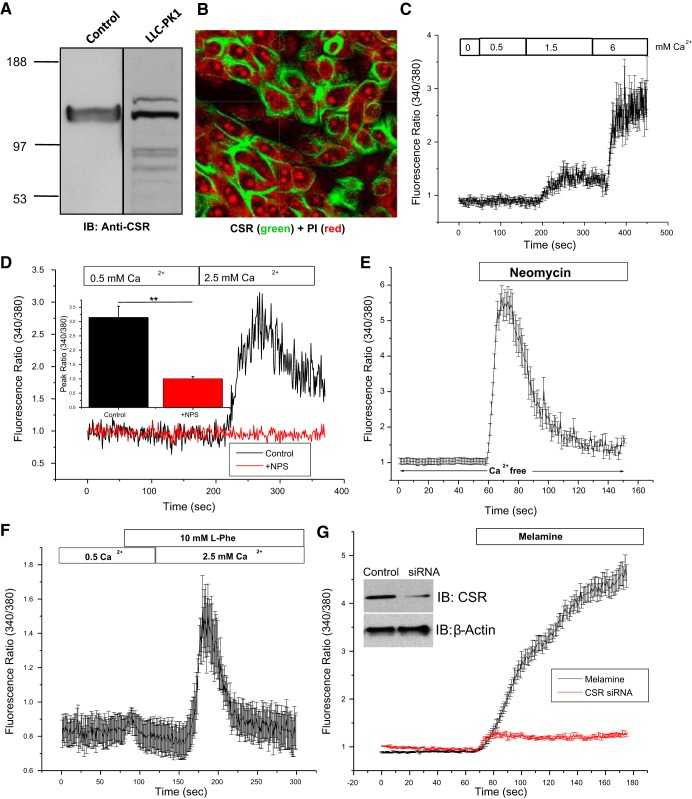

Because the melamine-induced effect in Ca2+ signaling depends on [Ca2+]o, and CSR has been reported to exert such an effect in several absorptive epithelial cell types (3, 4), we have examined the possibility of CSR involvement in melamine-induced rise in [Ca2+]i to explore the downstream effects such as apoptosis. We found that CSR is expressed on LLC-PK1 cells using both immunoblotting (Fig. 2A) and immunofluorescence (Fig. 2B) experiments and thus supports our claim that CSR might be involved in mediating Ca2+ signaling in LLC-PK1 cells. Thus, to define the CSR activation in LLC-PK1 cells, CSR agonists and antagonist were applied to measure [Ca2+]i mobilization. A concentration-dependent (0.5–6.0 mM) rise in [Ca2+]i, was seen when [Ca2+]o was applied (Fig. 2C). In contrast, CSR inhibitor, NPS 2143 (54), abolished such response in [Ca2+]i rise (Fig. 2D). The application of a potent CSR agonist, neomycin (500 µM), in Ca2+-free medium led to a sharp rise in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2E) attributable to a release of [Ca2+]i from ER store and neomycin binding directly to the Ca2+-binding site of CSR (42). In contrast, l-phe (10 mM) activation of CSR required the presence of [Ca2+]o (Fig. 2F), suggesting binding to the allosteric site of CSR that could modulate the CSR sensitivity to Ca2+ (7). Finally, treatment of CSR siRNA (5) to LLC-PK1 cells drastically reduced such Ca2+ response, confirming the effect of melamine on CSR in LLC-PK1 cells (Fig. 2G). Thus our data provide both molecular and pharmacological evidence of CSR activation in LLC-PK1 cells, which could have a functional significance in transcellular Ca2+ transport within the kidney (20).

Fig. 2.

Melamine induced a Ca2+ sensing in LLC-PK1 cells. A: immunoblotting (IB) using anti-calcium-sensing receptor (CSR) antibody (rabbit, 1:500 dilution) showing the expression of exogenous CSR protein in HEK (lane 1; control) and LLC-PK1 (lane 2). B: representative image of confocal XY sections of LLC-PK1 cells shows expression of CSR (green signal) and nuclei stained with propidium iodide (PI; red signal). C–F: mean fluorescence traces of fura-2 AM-loaded LLC-PK1 cells showing changes in fluorescence ratio (340/380 excitation) measured to assess the changes in [Ca2+]i evoked by elevating [Ca2+]o to cells bathed in Ca2+-free media. C: cells were bathed in Ca2+-free media and then exposed to a Ca2+ gradient (0.5–6.0 mM [Ca2+]o). D: cells were bathed in 0.5 mM Ca2+, and then 2.5 mM [Ca2+]o was applied with (NPS 2143, red trace) and without (control, black) CSR inhibitor. Inset: bar diagram of peak fluorescence ratio values in response to 2.5 mM [Ca2+]o. E: CSR activator, neomycin (500 µM), was added to cells in a Ca2+-free medium, causing a [Ca2+]i rise attributable to G protein-coupled receptor activation. F: l-phe (10 mM) induced activation of CSR, leading to intracellular release of Ca2+ in 0.5 mM Ca2+ media, followed by Ca2+ entry after application of 2.5 mM [Ca2+]o. G: melamine (3 mM) induces activation of CSR in LLC-PK1 cells in the presence of in 1.2 mM [Ca2+]o, which is further blocked by CSR-specific siRNA-treated LLC-PK1 cells (red trace). Cells were transiently transfected with CSR-specific siRNA (siCSR) and a scrambled (control) siRNA as described (5). Changes in [Ca2+]o and other conditions are indicated in the figure. Western blot (inset in G) using anti-CSR antibody confirms the inhibition of CSR proteins, where β-actin antibody labeling was used as a loading control. Values are means ± SE. **P < 0.01.

Melamine-induced CSR activation in LLC-PK1 cells causes prolonged Ca2+ entry.

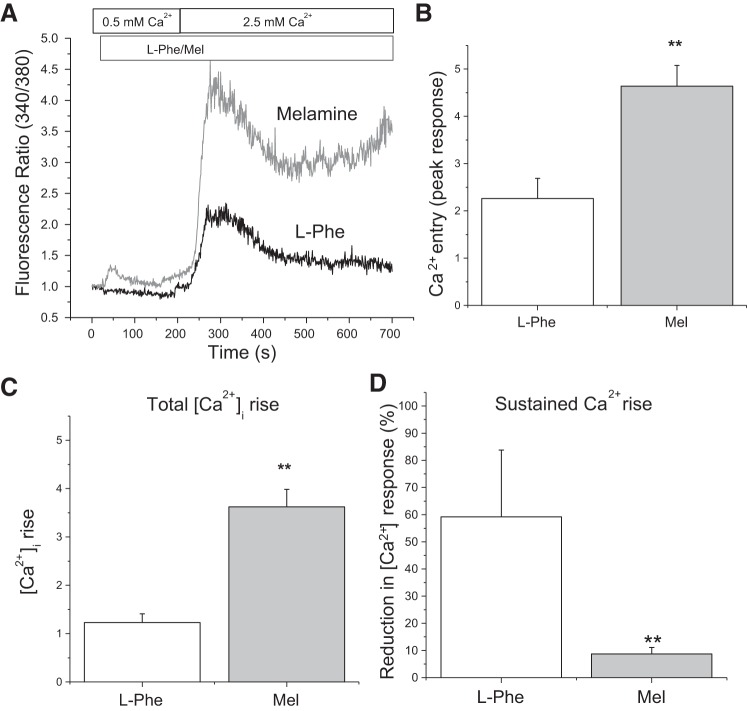

To explore the effects of melamine on Ca2+ signaling in LLC-PK1 cells, we performed Ca2+ imaging experiments to measure [Ca2+]i transients (Fig. 3). Our results from a Ca2+ readdition experiment in a minimally Ca2+-containing media (0.5 mM) show a rise in [Ca2+]i induced by melamine (3 mM) attributable to Ca2+ release, followed by a marked increase in [Ca2+]i after application of 2.5 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 3A), indicating Ca2+ entry (Fig. 3B represents peak response). Interestingly, application of melamine produced a prolonged Ca2+ response in which the [Ca2+]i normalization period was much greater than the time for l-phe-treated cells (Fig. 3C). l-phe (10 mM) was used as a control (an allosteric activator of CSR), which we have previously shown is involved in salivary ductal cell-transient Ca2+ entry (5). In contrast, Ca2+ entry induced by melamine in these cells was persistent and is characterized by a prolonged [Ca2+]i rise, suggesting sustained Ca2+ entry (Fig. 3D), whereas the cells treated with l-phe began to normalize rapidly with peak fluorescence ratios in contrast to cells treated with melamine.

Fig. 3.

CSR activation induced Ca2+ signaling by melamine in LLC-PK1 cells. A: mean fluorescence traces of fura-2 AM-loaded LLC-PK1 cells. Changes in the fluorescence ratio (340/380 excitation) were measured in cells bathed in 0.5 mM Ca2+-containing media; then 3 mM melamine (Mel; gray trace) and 10 mM l-phe (black trace) were applied, followed by a readdition of 2.5 mM [Ca2+]o in the media. Bar diagrams of the fluorescence ratio (340/380) in response to applied [Ca2+]o at peak (B) and at the conclusion of the experiment (C) represent a sustained [Ca2+]i rise in l-phe-treated (open bar) and melamine-treated (shaded bar) conditions. D: percentage reduction in l-phe-treated (open bar) and melamine-treated (shaded bar) cells between the peak 340/380 fluorescence ratio and end of Ca2+ imaging session. Values are means ± SE. **P < 0.01.

Melamine induced a Ca2+ current in LLC-PK1 cells.

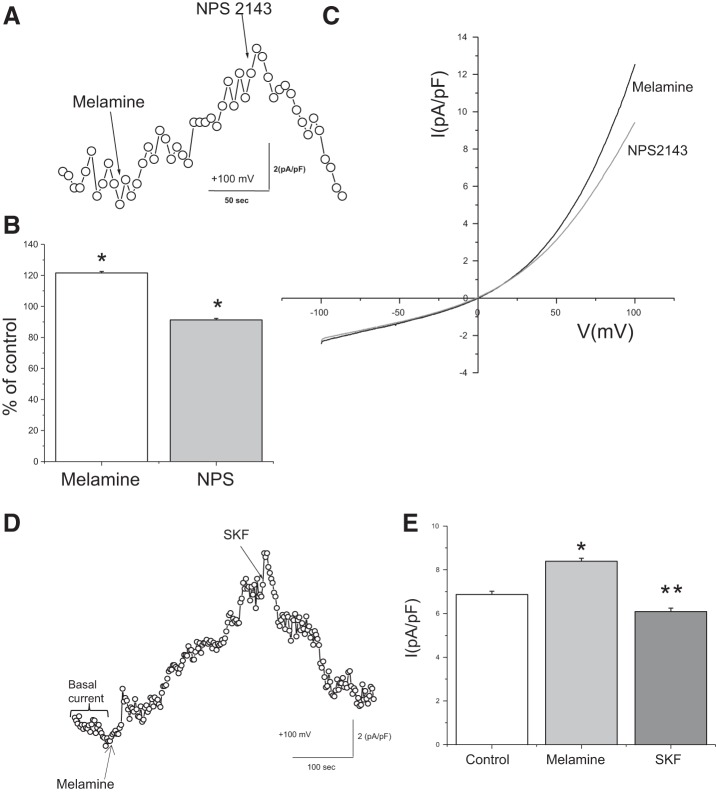

We also performed electrophysiology (patch-clamp) experiments to further observe the effect of melamine on Ca2+ entry in LLC-PK1 cells. Application of melamine (1–3 mM) in the presence of [Ca2+]o (1.2 mM) induced a nonselective cation current, which was blocked by CSR inhibitor NPS 2143 (1 µM; Fig. 4, A and B), suggesting that melamine-induced current had been generated as a result of the allosteric modulation of the CSR. I/V relationship of melamine-induced nonselective cation current shows (Fig. 4C) an outward rectification, typical for TRPC channels. Thus we performed electrophysiology experiments to examine whether such nonselective cation current is in fact attributable to the activation of TRPC channels. Application of SKF 96365, a general TRPC channel antagonist commonly used to characterize the physiological functions mediated by TRPC channels (40), significantly reduced melamine-induced current (Fig. 4, D and E), suggesting that melamine induced a TRPC current in LLC-PK1 cells.

Fig. 4.

Melamine generated a Ca2+ current in LLC-PK1 cells. A: whole cell patch-clamp recording (average data of 4 separate experiments) of LLC-PK1 cells, shown after application of melamine (3 µM) and its inhibition by CSR blocker (NPS 2143; 1 µM). B: bar diagram represents the current densities of melamine and NPS 2143 compared with the basal current at +100 mV after melamine (open bar) application and its effects on NPS 2143 (shaded bar). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05. C: average (3–4 separate experiments) data represent the I/V relationship of ramps from −100 mV to +100 mV before (control, black) and after (gray) melamine application. D: time course of whole cell current measurements in LLC-PK1 cells with Ca2+ (1.2 mM) containing extracellular solution are showing currents at +100 mV after exposure to melamine and SKF 96365 [transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channel blocker]. E: bar diagram represents current densities [compared with the basal current at +100 mV (open bar)] attributable to melamine (shaded bar) and the application of TRPC inhibitor (SKF 96365; dark shaded bar). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Melamine-induced CSR stimulation leading to enhanced ROS production.

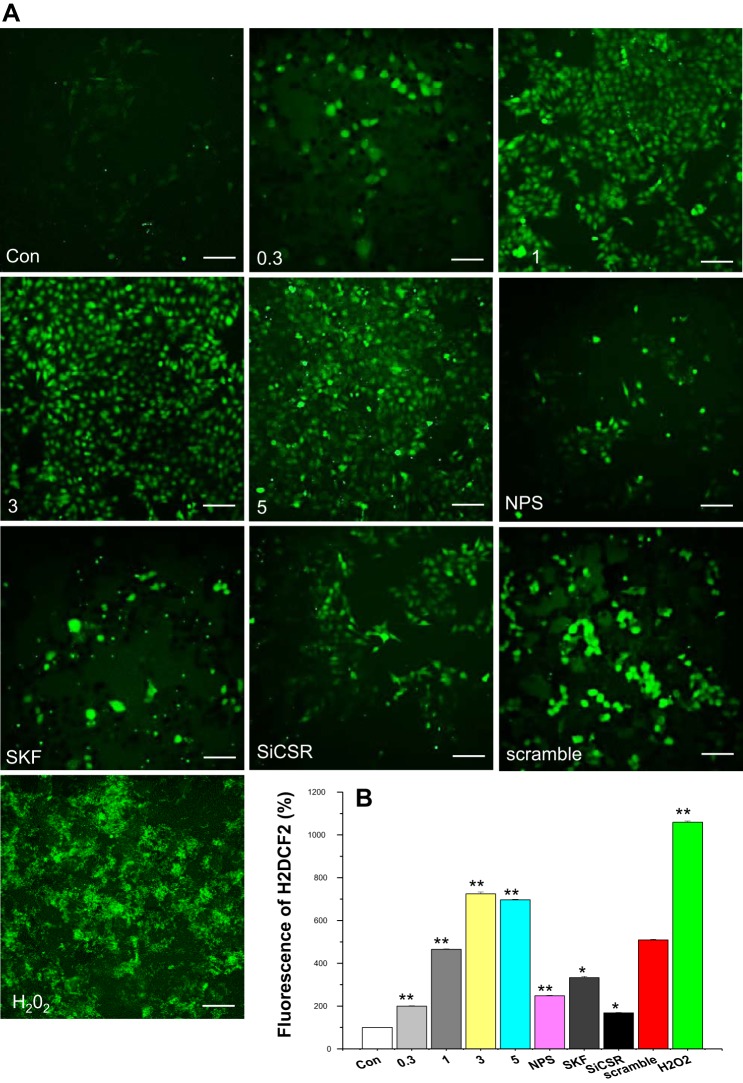

As above, our data show that melamine produced a sustained [Ca2+i] rise, which can develop ER stress-induced oxidative stress (18, 36). Oxidative stress has been described as a common regulator of melamine-induced ROS production in human renal tubular cells (25). Therefore, we examined whether melamine-stimulated Ca2+ signaling can regulate ROS generation in LLC-PK1 cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, the applications of melamine dose dependently (0.3–3.0 mM) increase the positive staining of H2DCFDA (green fluorescence), suggesting the rise in ROS production. Furthermore, to link the mechanism of melamine-induced CSR-stimulated Ca2+ signaling and ROS production, we used NPS 2143 as a pharmacological blocker for CSR and SKF 96365 as a TRPC channel blocker. Our data show that H2DCFDA fluorescence was significantly reduced in both cases (Fig. 5, A and B), suggesting that melamine exerts its effect on ROS production via CSR-stimulated TRPC-mediated Ca2+ signaling and ER stress response (18). We confirmed these results by blocking of ROS generation (Fig. 5B) using specific (scramble siRNA did not block) siRNA inhibitors of CSR (siCSR).

Fig. 5.

Melamine-induced CSR stimulated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in LLC-PK1 cells. A: cells were treated with 0.3–5.0 mM (0.3, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0 as indicated) of melamine in the presence and absence of 10 nM NPS 2143 (NPS), 100 nM SKF 96365 (SKF), CSR-specific siRNA (siCSR), and control siRNA (scramble) for 18 h before incubation with 10 μM H2DCFDA. Untreated cells were used as negative control (Con), and the cells treated with H2O2 (100 μM) were used as positive control. H2DCFDA fluorescence was examined under a microscope, and the data were quantified as indicated in materials and methods. Representative images of cells are from 3 independent experiments. Scale bar = 90 μm. B: bar diagram represents fluorescence intensity percentage change indicator of ROS production in treated cells compared with control (untreated cells) and calculated as described in materials and methods. Each reported value represents the mean ± SE from 3 to 4 independent experiments (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with untreated control). NPS-, SKF-, and siRNA-treated cells, including control (scramble) siRNA, were compared with 3 mM melamine-treated cells.

Melamine induces apoptosis in LLC-PK1 calls via CSR-mediated Ca2+ signaling pathway.

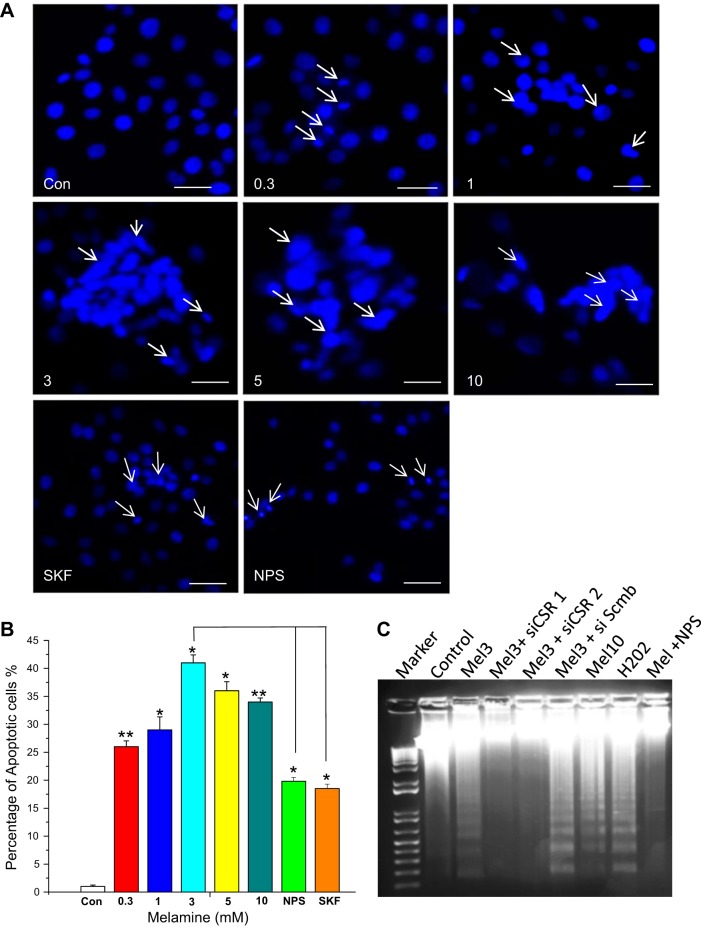

DNA fragmentations, apoptotic body formations, and nuclear condensations are known as hallmarks of apoptosis, which are usually determined by the examination of DNA laddering and DAPI staining methods (19, 23). Therefore, to understand the upstream mechanism of melamine-induced apoptosis, we performed DAPI staining by treating the LLC-PK1 cells with several doses of melamine (0.3–10.0 mM). Our data show that melamine produced a dose-dependent (0.3–5.0 mM) increase in apoptotic cells (Fig. 6, A and B). However, those apoptotic cells were slightly decreased from 3 to 10 mM, suggesting that the apoptosis process starts at a low dose (0.3) of melamine and reached a maximum at 3 mM of melamine. Most nuclear condensations and apoptotic body formations were also detected in cells treated with 3 mM melamine. Furthermore, to link the mechanism of melamine-induced CSR-stimulated Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis, we used a pharmacological blocker for CSR (NPS 2143) and a TRPC channel blocker, SKF 96365, to examine the apoptotic cell formation. Apoptotic cells were reduced significantly in both cases (Fig. 6, A and B), indicating that melamine-stimulated TRPC-mediated Ca2+ signaling contributes to apoptosis in LLC-PK1 cells.

Fig. 6.

Melamine-induced DNA damage and fragmentation influenced by CSR-mediated pathway. A: to examine the DNA damage, LLC-PK1 cells were exposed to melamine for 18 h with 0.3–10.0 mM (0.3, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0 and 10.0 as indicated), in the presence and absence of inhibitors of CSR (300 nM NPS 2143) and TRPC channels (100 nM SKF 96365), before staining with DAPI (1 μg/ml). White arrows indicate apoptotic nuclei. Untreated cells were used as control. Scale bar = 100 μm. B: bar diagram represents percentage of apoptotic cells as an indicator of apoptosis compared with control and calculated as described in materials and methods. Each reported value represents the mean ± SE from 3 to 4 independent experiments (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01compared with untreated control). NPS- and SKF-treated cells were compared with 3 mM melamine-treated cells. C: detection of DNA fragmentation by agarose gel electrophoresis in LLC-PK1 cells induced by melamine. Lanes are marked as indicated; Control, untreated cells; Mel3, 3 mM melamine; Mel10, 10 mM melamine; siCSR, CSR-specific siRNA; siCSR 2, CSR-specific siRNA 2; si Scmb, control (nonspecific) siRNA; NPS, NPS 2143 (CSR inhibitor); H2O2 (100 μM) was used as positive control. Cells were transiently transfected with siCSR. DNA was isolated and subjected to ethidium bromide 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Details are described in materials and methods. Typical fragmented DNA in gel electrophoresis image shown is the representation of 3 independent experiments.

Because the laddering of DNA has been found in almost all apoptotic cells, DNA fragmentation is the strongest marker for apoptosis (19). Thus, to determine such apoptosis-induced DNA damage, we treated LLC-PK1 cells with melamine to perform the DNA laddering experiment. Our results in Fig. 6C show a very visible DNA laddering with 3 and 10 mM of melamine. Such DNA fragmentation was blocked by using specific siRNA inhibitors of CSR (siCSR) (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, using pharmacological blocker of CSR (NPS 2143), also blocked the DNA fragmentation (Fig. 6C), suggesting CSR as a regulator of melamine-induced apoptotic process.

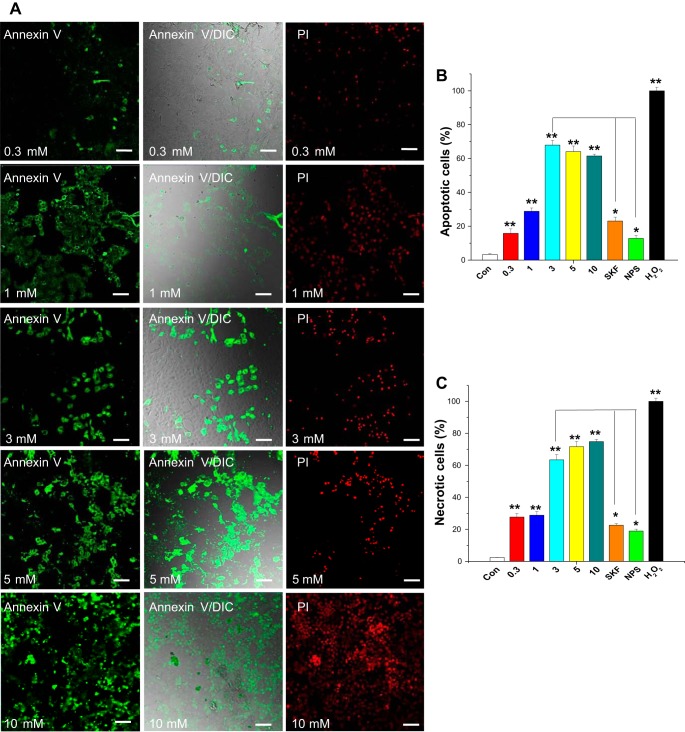

Melamine-induced CSR activation leads to apoptosis.

Melamine can initiate and induce apoptosis (21, 25); however, the mechanism of such induction in the apoptotic process is unknown. Activation of CSR has been shown to induce apoptosis in different cell types via [Ca2+]i pathway (47). Therefore, to link the upstream mechanism, i.e., CSR-induced [Ca2+]i rise and to what extent such pathway leads to apoptosis, we used Alexa Fluor 488-labeled annexin-V and PI labeling in LLC-PK1 cells with several doses of melamine (0.3–10.0 mM) and the presence of melamine under different physiological conditions that influence the CSR pathway (Fig. 7A). We found that melamine induced a dose-dependent increase in apoptotic and necrotic cells, which was greatly reduced by addition of NPS 2143 (Fig. 7, B and C), indicating melamine acting through CSR to mediate those effects. Furthermore, to confirm whether the regulation of apoptotic and necrotic cell death are through CSR-mediated Ca2+ signaling pathway, we used SKF 96365. Our data show a marked reduction in both apoptotic and necrotic cell death (Fig. 7, A–C), suggesting that melamine-stimulated CSR is the upstream mechanism of melamine-induced cell death.

Fig. 7.

Melamine induces apoptosis through CSR-mediated Ca2+ signaling in LLC-PK1 cells. A: representative images show LLC-PK1 cells undergoing both apoptosis [using Alexa Fluor 488-labeled annexin V (green signal; left)] and necrosis [using PI (red signal; right). Differential staining was performed to determine melamine-induced apoptosis and necrosis in live cells. Middle: overlay of differential interference contrast (DIC) pictures with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled annexin V. LLC-PK1 cells were exposed to melamine for 18 h with 0.3–10.0 mM (0.3, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, and 10.0 as indicated). Cells are also treated with 3 mM melamine in the presence and absence of inhibitors of CSR (300 nM NPS 2143) and TRPC channels (100 nM SKF 96365), before staining with annexin-V/PI. Untreated cells were used as control. Scale bar = 100 μm. B: bar diagram represents percentage of apoptotic cells (bright green fluorescence) as an indicator of apoptosis compared with control and calculated as described in materials and methods. C: quantification of necrosis shown in bar diagram shown as percentage of necrotic cells (red fluorescence) compared with control. Images are from 3 independent experiments showing cell populations undergoing apoptosis and necrosis, which were quantified and expressed as percentage of total cells. Each value represents the mean ± SE (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01) compared with control (untreated). NPS- and SKF-treated cells were compared with cells treated with 3 mM melamine. H202-treated (100 μM) cells were used as positive control.

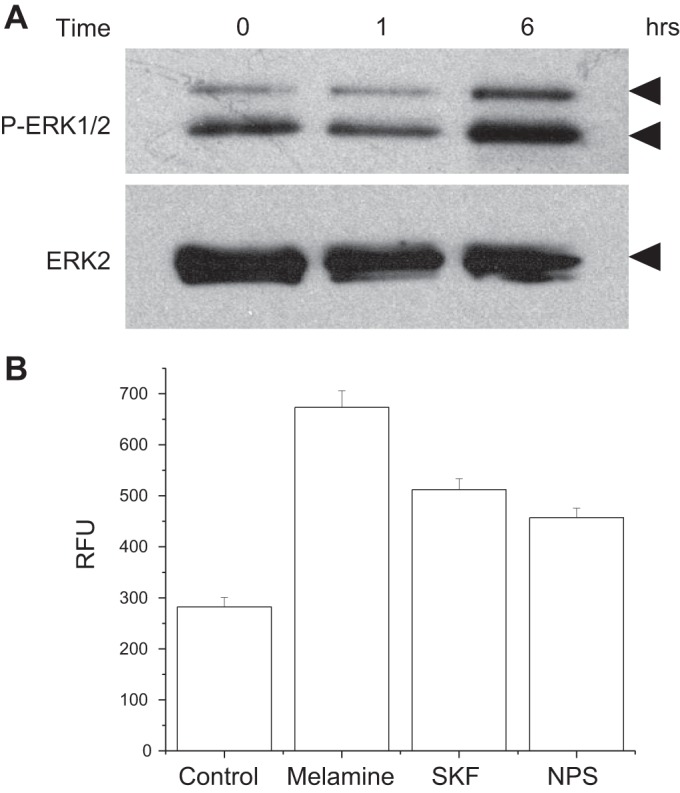

Melamine-induced pERK activation and LDH activity.

To further explore the pathway of melamine-induced apoptosis downstream from [Ca2+]i increase, we looked at the ERK activation, which is also linked to apoptosis (35). A time-dependent increase of ERK phosphorylation was observed following treatment of 3 mM melamine (Fig. 8A), suggesting that melamine can exert its effect on apoptosis in LLC-PK1 cells via a pERK activation. To further determine whether melamine can induce necrosis through the activation of CSR, we measured LDH activity (10). Enhanced LDH activity was shown in rat proximal tubular epithelial cells treated with melamine (25). Figure 8B represents increased LDH production in melamine-treated LLC-PK1 cells, which was released in the culture media of cells. LDH production was significantly reduced when both CSR inhibitor (NPS 2143) and a TRPC channel inhibitor were included with melamine (3 mM), suggesting that melamine activation of CSR-mediated Ca2+ signaling can lead to cellular cytotoxicity and necrosis (10).

Fig. 8.

Melamine-induced ERK pathway activation and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release. A: Western blots showing that melamine activates the pERK pathway. LLC-PK1 cells were exposed to 3 mM melamine in a physiological Ca2+-containing media for various durations (0–6 h), and the results were analyzed by Western blots using antibodies to phospho-ERK1/2 and ERK2 (control) antibodies. B: to determine the LDH release, LLC-PK1 cells were treated with 3 mM melamine, 3 mM melamine plus 100 nM SKF 96365, or 3 mM melamine with 300 nM NPS 2143 over 12 h. Untreated cells were used as control. LDH activity is shown as relative fluorescence units (RFU). Data represent means ± SE.

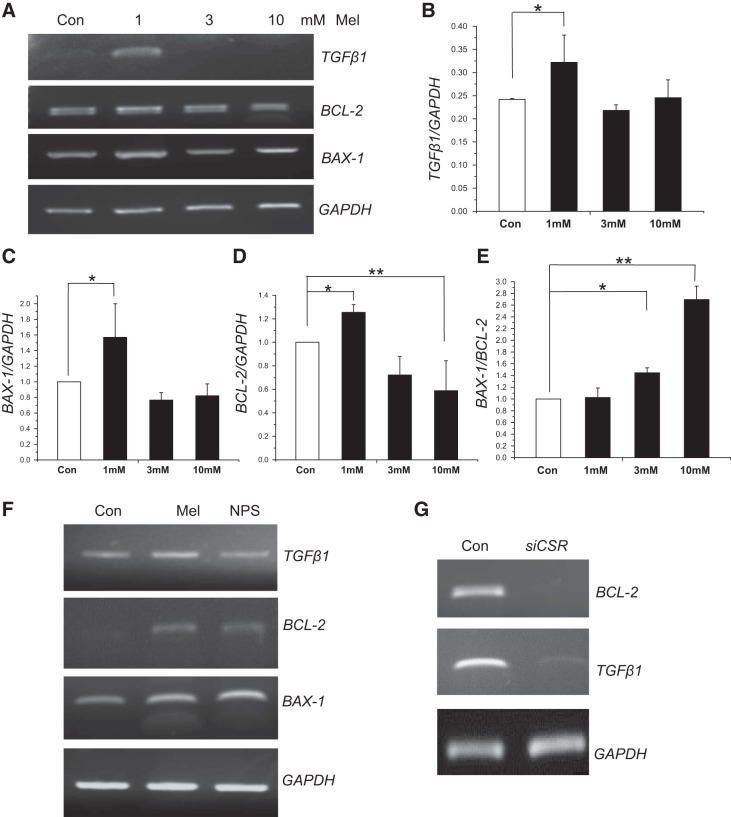

Melamine-induced Ca2+signaling and proapoptotic pathway activation.

Both BCL-2 and BAX-1 are the transcriptional regulators of apoptosis in response to DNA damage and ER stress (18). BCL-2 binds to and inactivates BAX-1 and other proapoptotic proteins, thereby inhibiting apoptosis through caspase-mediated pathway (49). Melamine was shown to induce such a proapoptotic pathway in HK2 cells; however, the mechanism of melamine-induced Ca2+ signaling in this process is unknown. Melamine also induces the expression of TGF-β1 to promote fibronectin production leading to renal tubular cell injury (25). Therefore, to delineate the mechanism of CSR-stimulated Ca2+ signaling and how this process may be connected to proapoptotic pathway activation, we performed RT-PCR experiments to examine the mRNA expression of TGF-β1, BAX-1 and BCL-2 (Fig. 9, A–D). Melamine induced TGF-β1 expression (Fig. 9, A and B) only at low doses (1 mM), which have been shown to release profibrotic cytokines to cause renal tubular cell damage, upregulated by oxidative stress (17, 51), whereas, in higher doses melamine may be causing necrosis, which could be independent of TGF-β1 pathway. Figure 9, A and C, shows an induction in apoptosis-triggering gene, BAX-1, in response to apoptotic stimuli, which was increased in low doses and decreased in high doses of melamine, possible attributable to switching to a necrotic pathway. An upregulation of expression of antiapoptotic gene, BCL-2 in Fig. 9, A and D, indicates that mitochondria-mediated apoptosis may not be turned on in the presence of low doses of melamine. Interestingly, Fig. 9E shows an upregulation in the BAX-1/BCL-2 ratio, which can activate mitochondria-mediated apoptosis as shown during increased mitochondrial stress, resulting in renal injury. Melamine treatment in LLC-PK1 cells shows a dose-dependent (1–10 mM) increase of such BAX-1/BCL-2 ratio, indicating the activation of mitochondria apoptosis. To confirm the mechanism of melamine-induced CSR-stimulated proapoptotic pathway activation, we used NPS 2143 as a pharmacological inhibitor of CSR (Fig. 9F) and siRNA inhibitors (Fig. 9G) in the presence (3 mM) and absence (control) of melamine. We found that the mRNA expressions of both TGF-β1 and BCL-2 were markedly reduced under those melamine-induced conditions, suggesting that melamine activates both profibrotic and mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway, leading to renal tubular cell damage (25, 48).

Fig. 9.

Melamine-induced fibrotic and apoptotic gene expression in LLC-PK1 cells. To observe the melamine-induced fibrotic (transforming growth factor β1, TGF-β1) and apoptotic (BCL-2 and BAX-1) gene expression, cells were treated with 1 mM, 3 mM, and 10 mM of melamine for 18 h. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The mRNA was detected by semiquantitative RT-PCR. The PCR products were examined on a 1% agarose gel with ethidium bromide (A). The intensities of PCR products were determined by densitometric analysis. B–E: bar diagrams are the relative mRNA expression of the genes TGFβ1 (B), BAX-1 (C), BCL-2 (D), and BAX-1/BCL-2 (E) as apoptotic index. The error bar indicates the variation of the experiments. Data represent means ± SE. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with control. F and G: agarose gel images of semiquantitative RT-PCR experiments using pharmacological (NPS 2143) and siRNA inhibitors of inhibitor of CSR. The PCR products were examined on a 1% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining. Expressions are of GAPDH used as an internal control. mRNA expressions of both TGFβ1 and BCL2 were markedly reduced in NPS 2143-treated condition, which were confirmed by CSR-specific siRNA treatment.

DISCUSSION

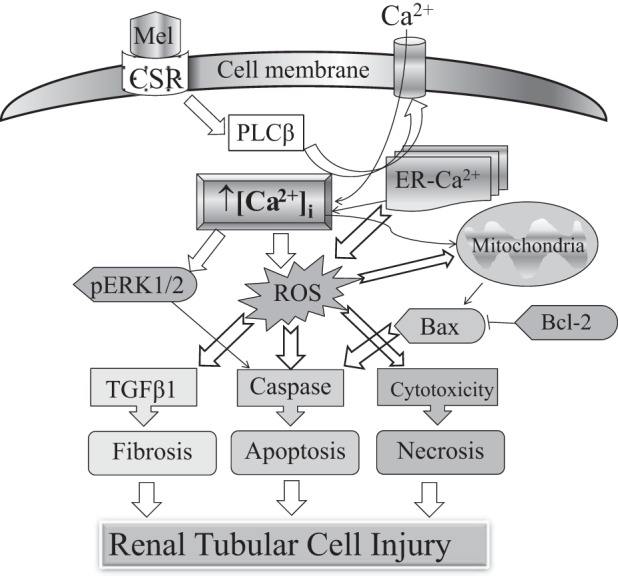

These data presented above show for the first time using porcine renal tubular cells that melamine can allosterically activate CSR and generate a PLC-β-mediated ER store release followed by Ca2+ entry, leading to a rise in [Ca2+]i. Such elevation of [Ca2+]i, possibly caused by a TRPC channel-mediated Ca2+ entry, could be due to an ER store release or via a direct activation. Unlike l-phe, melamine-stimulated CSR-mediated Ca2+ signaling resulted in a sustained Ca2+ entry, which can prolong the rise in [Ca2+]i. This mechanism might produce an ER stress response, thus resulting in ROS generation. Such an increase in [Ca2+]i and ROS generation further initiate the downstream DNA damage resulting in apoptotic and necrotic cell death. We propose that melamine induced a sustained rise in [Ca2+]i together with ROS generation to produce a caspase-mediated apoptosis pathway leading to tubular cell injury. Such cell damage could be also be mediated through 1) activation of mitochondrial proapoptotic (BAX-1/BCL-2) pathway, 2) expression of TGF-β1, promoting fibronectin production, and 3) ROS-mediated cytotoxicity resulting in necrosis. Furthermore, melamine-induced sustained [Ca2+]i increase can also cause ER stress response to activate pERK1/2, leading to tubular cell damage. A schematic diagram (Fig. 10) summarizes a possible mechanism of action of melamine.

Fig. 10.

A schematic diagram summarized as a possible mechanism of action of melamine causing tubular cell injury via CSR-mediated Ca2+ signaling pathway. Melamine activates CSR and generates a PLC-β-mediated Ca2+ entry, leading to a rise in [Ca2+]i, causing sustained Ca2+ entry, which could be attributable to an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) store depletion. Such prolonged elevation in [Ca2+]i can in turn produce an ER stress response, subsequently induce ROS generation, which further can initiate the downstream DNA damage, resulting in apoptotic and necrotic cell death, leading to tubular cell injury. Melamine-induced CSR activation leads to ROS generation that subsequently activates(AKI the following pathways to mediate tubular cell death: 1) activation of mitochondrial proapoptotic (BAX/BCL-2) pathway, 2) expression of TGF-β1, promoting fibronectin production, 3) cytotoxicity resulting in necrosis, and 4) caspase activation via pERK1/2.

Overall, our data reveal a mechanism for melamine-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i and apoptosis through the activation of CSR. Disturbance in [Ca2+]i homeostasis and the subsequent ER stress have been shown to induce apoptosis and/or necrosis (1). For example, albumin induced the activation of Ca2+-signaling mechanisms, increasing [Ca2+]i levels through Ca2+ store release and Ca2+ entry, and triggering ER stress and apoptosis (11). Interestingly, melamine induced a sustained [Ca2+]i response, a component that can cause ER stress (2). In our comparative experiment between melamine and l-phe, a known activator and modulator of CSR (5, 15), melamine-induced [Ca2+]i rise was sustained for a longer period. Such a process can cause a disturbance in apico-basal [Ca2+]i mobilization required for transepithelial Ca2+ transport (4), which we did not explore because of the limited scope of this study. Indeed, such a consequent compromise in Ca2+ clearance attributable to the exposure of melamine from contaminated food could have an implication in noncyanurate stone formation, such as the calcium phosphate/calcium oxalate stones (41). Furthermore, the oxidative stress, lipids, and cell debris are all factors to crystal growth in such noncyanurate kidney stone formation (27). Although some clinical studies indicate the predisposing scenario (16, 32), future studies are required to explore these additional effects of melamine exposure and its pathophysiological relevance. Furthermore, a melamine-induced continuous rise in [Ca2+]i-exhausting ER Ca2+ stores could stimulate capacitive Ca2+ influx and thus can lead to prolonged Ca2+ entry (47) and initiate [Ca2+]i-mediated apoptosis (35). Melamine-induced ROS generation and caspase activation leading to apoptosis are the known indicators of renal tubular cell injury (21, 25). However, there is an open possibility that the melamine-induced rise in sustained [Ca2+]i may further prolong ER Ca2+ to activate apoptotic machinery that could operate well by a store-operated Ca2+ entry mechanism (39), exploration of which can add additional knowledge to the mechanism. In addition, the [Ca2+]o signaling effect of melamine might have the possibility to open a new door toward finding the new modulators of CSR. However, such exploration to find a melamine-like compound may have hurdles to cross to reduce the toxic effect of melamine.

Although the downstream mechanisms of melamine-induced apoptosis and necrosis have been extensively studied, our results show for the first time a critical role of Ca2+ influx in this process. Indeed, our approach was to understand how melamine regulates the process of apoptosis/necrosis by involving Ca2+ influx and [Ca2+]i accumulation. We show a drastic reduction in the number of apoptotic and necrotic cells because of the inhibition of CSR and CSR-stimulated Ca2+ signaling pathway. Similarly, melamine-treated cells exhibited an increase in LDH release, which were also dampened by the inhibitors of CSR-induced Ca2+ signaling pathway. Moreover, comparison between doses of melamine-treated cells shows greater incidences of apoptosis then necrosis at lower doses, whereas necrosis starts during exposure to higher doses (23, 52). Our explanation is that the first phase of melamine activation at low to moderate doses may deplete ER Ca2+ stores and further stimulate Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane, thus producing a prolonged [Ca2+]i rise in the cytosol attributable to sustained Ca2+ entry, leading to ER stress and apoptosis (55). In contrast, moderate to high doses of melamine induce cytotoxicity, resulting in necrosis. This could be involved in the ER mitochondria Ca2+ transfer mechanism (38), activating the mitochondrial cell death pathway. Because we used LLC-PK1 cells, a proximal tubular cell line, we propose that such tubular cell injury and cell death can produce cell debris, which can well be a contributing factor in the downstream process of the growth phase of stone formation (41).

In our search for the clinical relevance of melamine-induced renal toxicity, we found that crystal formation occurs when melamine is mixed with cyanuric acid or uric acid (16). However, increasing evidence has shown that melamine itself has toxic effects. Guo et al. (21) have found that ~1,000 μg/ml melamine can lead to excess intracellular ROS production, resulting in apoptosis in the rat renal proximal tubule cell line, NRK-52e. Additionally, some others have reported that 250 μg/ml melamine increases ROS production and expression of the genes before apoptosis in a human proximal tubular cell line, HK2 (25). However, all these in vitro studies tried to clarify the long-term exposure of melamine. In our experiments, we tested the 3 mM (~378 mg/l) melamine effect on CSR because in our previous study we used 5–20 mM structurally similar l-amino acids such as l-phe and l-try to activate CSR to observe the physiological effect in similar tubular epithelial cells (5). In addition, we also have tested a wide range of concentrations (0.3–10.0 mM) to map out the Ca2+ signaling-mediated apoptotic and necrotic effects. Our results show that 3 mM is near the optimum concentration to cause those effects of tubular cell injury. Moreover, the basis of melamine concentrations used in this study are also based on several in vitro and in vivo preclinical and clinical studies (21, 25, 26, 50). Accordingly, in a melamine toxicity study, the serum mean concentration was 1295.3 mg/kg in children exposed to formula contaminated with melamine, resulting in high toxicities with stone-forming features (26), which is much higher than what we have used. We propose that melamine should act similar to those l-amino acids, to which kidney proximal tubular cells are exposed apically. However, it would be difficult to estimate such an amount present in proximal tubular fluid until an in vivo measurement is performed, which is beyond the scope of the present study. We proposed that persistent exposure to low levels of melamine from sources we use daily (such as plastic ware) could also pose a risk to adults and form stones.

When combined with cyanuric acid, a melamine analog, melamine has a greater nephrotoxic effect (16), which is shown to form crystals in both the proximal and distal tubules in rats (12). Interestingly, when cyanuric acid is not present, melamine and uric acid combine in the urine and form melamine–uric acid stones (16). Thus, in addition to the melamine-induced apoptosis in proximal tubular cells, further studies are required to understand the melamine-related crystal injury, which could further enhance cell death and may increase the risk of noncyanurate stone formation. Pathogenesis of stone formation is a multistep process in which the proximal tubule cell injury attributable to melamine exposure and also the cells from downstream tubular segments can be damaged. Thus the exploration of those events is necessary to determine the overall role of melamine exposure in invoking the injury to those tubular epithelial linings, such as in the distal tubules and the collecting ducts, and contributing anchoring crystals to facilitate the process of kidney stone formation.

GRANTS

This study was supported in part by a Joseph M. Krainin, M.D. Memorial Young Investigator Award from National Kidney Foundation of the National Capital Area and National Institutes of Health Grant DK-102043 (to B. Bandyopadhyay). Both funding sources had no involvement in the preparation of the article, study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.C.B. conceived and designed research; A.J.Y., C.-L.I., S.K.R., and B.C.B. performed experiments; A.J.Y., C.-L.I., S.K.R., and B.C.B. analyzed data; A.J.Y., C.-L.I., S.K.R., and B.C.B. interpreted results of experiments; A.J.Y., C.-L.I., S.K.R., and B.C.B. prepared figures; A.J.Y. and B.C.B. drafted manuscript; A.J.Y., C.-L.I., S.K.R., and B.C.B. edited and revised manuscript; A.J.Y., C.-L.I., S.K.R., and B.C.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ajay Potluri and Linda Mbianda for technical help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bahar E, Kim H, Yoon H. ER Stress-mediated signaling: action potential and Ca(2+) as key players. Int J Mol Sci 17: E1558, 2016. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahar E, Lee GH, Bhattarai KR, Lee HY, Choi MK, Rashid HO, Kim JY, Chae HJ, Yoon H. Polyphenolic extract of euphorbia supina attenuates manganese-induced neurotoxicity by enhancing antioxidant activity through regulation of ER stress and ER stress-mediated apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci 18: E300, 2017. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandyopadhyay BC, Pingle SC, Ahern GP. Store-operated Ca2+ signaling in dendritic cells occurs independently of STIM1. J Leukoc Biol 89: 57–62, 2011. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0610381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandyopadhyay BC, Swaim WD, Liu X, Redman RS, Patterson RL, Ambudkar IS. Apical localization of a functional TRPC3/TRPC6-Ca2+-signaling complex in polarized epithelial cells. Role in apical Ca2+ influx. J Biol Chem 280: 12908–12916, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandyopadhyay BC, Swaim WD, Sarkar A, Liu X, Ambudkar IS. Extracellular Ca(2+) sensing in salivary ductal cells. J Biol Chem 287: 30305–30316, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.394122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bánfi B, Tirone F, Durussel I, Knisz J, Moskwa P, Molnár GZ, Krause KH, Cox JA. Mechanism of Ca2+ activation of the NADPH oxidase 5 (NOX5). J Biol Chem 279: 18583–18591, 2004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bräuner-Osborne H, Jensen AA, Sheppard PO, O’Hara P, Krogsgaard-Larsen P. The agonist-binding domain of the calcium-sensing receptor is located at the amino-terminal domain. J Biol Chem 274: 18382–18386, 1999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brismar H, Asghar M, Carey RM, Greengard P, Aperia A. Dopamine-induced recruitment of dopamine D1 receptors to the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 5573–5578, 1998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown EM, Gamba G, Riccardi D, Lombardi M, Butters R, Kifor O, Sun A, Hediger MA, Lytton J, Hebert SC. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca(2+)-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature 366: 575–580, 1993. doi: 10.1038/366575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan FK, Moriwaki K, De Rosa MJ. Detection of necrosis by release of lactate dehydrogenase activity. Methods Mol Biol 979: 65–70, 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-290-2_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen S, He FF, Wang H, Fang Z, Shao N, Tian XJ, Liu JS, Zhu ZH, Wang YM, Wang S, Huang K, Zhang C. Calcium entry via TRPC6 mediates albumin overload-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in podocytes. Cell Calcium 50: 523–529, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YT, Jiann BP, Wu CH, Wu JH, Chang SC, Chien MS, Hsuan SL, Lin YL, Chen TH, Tsai FJ, Liao JW. Kidney stone distribution caused by melamine and cyanuric acid in rats. Clin Chim Acta 430: 96–103, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu WT, Wang YH, Tang MJ, Shen MR. Soft substrate induces apoptosis by the disturbance of Ca2+ homeostasis in renal epithelial LLC-PK1 cells. J Cell Physiol 212: 401–410, 2007. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell 131: 1047–1058, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conigrave AD, Quinn SJ, Brown EM. L-amino acid sensing by the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4814–4819, 2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalal RP, Goldfarb DS. Melamine-related kidney stones and renal toxicity. Nat Rev Nephrol 7: 267–274, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Disel U, Paydas S, Dogan A, Gulfiliz G, Yavuz S. Effect of colchicine on cyclosporine nephrotoxicity, reduction of TGF-beta overexpression, apoptosis, and oxidative damage: an experimental animal study. Transplant Proc 36: 1372–1376, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong M, Hu N, Hua Y, Xu X, Kandadi MR, Guo R, Jiang S, Nair S, Hu D, Ren J. Chronic Akt activation attenuated lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac dysfunction via Akt/GSK3β-dependent inhibition of apoptosis and ER stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832: 848–863, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Mouedden M, Laurent G, Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Tulkens PM. Gentamicin-induced apoptosis in renal cell lines and embryonic rat fibroblasts. Toxicol Sci 56: 229–239, 2000. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/56.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goel M, Sinkins WG, Zuo CD, Estacion M, Schilling WP. Identification and localization of TRPC channels in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1241–F1252, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00376.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo C, Yuan H, He Z. Melamine causes apoptosis of rat kidney epithelial cell line (NRK-52e cells) via excessive intracellular ROS (reactive oxygen species) and the activation of p38 MAPK pathway. Cell Biol Int 36: 383–389, 2012. doi: 10.1042/CBI20110504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hau AK, Kwan TH, Li PK. Melamine toxicity and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 245–250, 2009. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008101065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Healy E, Dempsey M, Lally C, Ryan MP. Apoptosis and necrosis: mechanisms of cell death induced by cyclosporine A in a renal proximal tubular cell line. Kidney Int 54: 1955–1966, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature 397: 259–263, 1999. doi: 10.1038/16711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh TJ, Hsieh PC, Tsai YH, Wu CF, Liu CC, Lin MY, Wu MT. Melamine induces human renal proximal tubular cell injury via transforming growth factor-β and oxidative stress. Toxicol Sci 130: 17–32, 2012. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu P, Wang J, Hu B, Lu L, Zhang M. Clinical observation of childhood urinary stones induced by melamine-tainted infant formula in Anhui province, China. Arch Med Sci 9: 98–104, 2013. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.33350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonassen JA, Cao LC, Honeyman T, Scheid CR. Intracellular events in the initiation of calcium oxalate stones. Nephron Exp Nephrol 98: e61–e64, 2004. doi: 10.1159/000080258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiyonaka S, Kato K, Nishida M, Mio K, Numaga T, Sawaguchi Y, Yoshida T, Wakamori M, Mori E, Numata T, Ishii M, Takemoto H, Ojida A, Watanabe K, Uemura A, Kurose H, Morii T, Kobayashi T, Sato Y, Sato C, Hamachi I, Mori Y. Selective and direct inhibition of TRPC3 channels underlies biological activities of a pyrazole compound. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5400–5405, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808793106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo FC, Tseng YT, Wu SR, Wu MT, Lo YC. Melamine activates NFκB/COX-2/PGE2 pathway and increases NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS production in macrophages and human embryonic kidney cells. Toxicol In Vitro 27: 1603–1611, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu CC, Wu CF, Chen BH, Huang SP, Goggins W, Lee HH, Chou YH, Wu WJ, Huang CH, Shiea J, Lee CH, Wu KY, Wu MT. Low exposure to melamine increases the risk of urolithiasis in adults. Kidney Int 80: 746–752, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Bandyopadhyay BC, Singh BB, Groschner K, Ambudkar IS. Molecular analysis of a store-operated and 2-acetyl-sn-glycerol-sensitive non-selective cation channel. Heteromeric assembly of TRPC1-TRPC3. J Biol Chem 280: 21600–21606, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu X, Wang J, Cao X, Li M, Xiao C, Yasui T, Gao B. Gender and urinary pH affect melamine-associated kidney stone formation risk. Urol Ann 3: 71–74, 2011. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.82171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mogami H, Lloyd Mills C, Gallacher DV. Phospholipase C inhibitor, U73122, releases intracellular Ca2+, potentiates Ins(1,4,5)P3-mediated Ca2+ release and directly activates ion channels in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Biochem J 324: 645–651, 1997. doi: 10.1042/bj3240645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, Li E, Xu J, Yankner BA, Yuan J. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature 403: 98–103, 2000. doi: 10.1038/47513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nawaz M, Manzl C, Lacher V, Krumschnabel G. Copper-induced stimulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in trout hepatocytes: the role of reactive oxygen species, Ca2+, and cell energetics and the impact of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling on apoptosis and necrosis. Toxicol Sci 92: 464–475, 2006. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ong HL, Liu X, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Singh BB, Bandyopadhyay BC, Swaim WD, Russell JT, Hegde RS, Sherman A, Ambudkar IS. Relocalization of STIM1 for activation of store-operated Ca(2+) entry is determined by the depletion of subplasma membrane endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) store. J Biol Chem 282: 12176–12185, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609435200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B, Nicotera P. Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 552–565, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nrm1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinton P, Giorgi C, Siviero R, Zecchini E, Rizzuto R. Calcium and apoptosis: ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer in the control of apoptosis. Oncogene 27: 6407–6418, 2008. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Putney JW., Jr Capacitative calcium entry revisited. Cell Calcium 11: 611–624, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90016-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rae MG, Hilton J, Sharkey J. Putative TRP channel antagonists, SKF 96365, flufenamic acid and 2-APB, are non-competitive antagonists at recombinant human α1β2γ2 GABA(A) receptors. Neurochem Int 60: 543–554, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Renkema KY, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. Role of the calcium-sensing receptor in reducing the risk for calcium stones. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2076–2082, 2011. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00480111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riccardi D, Hall AE, Chattopadhyay N, Xu JZ, Brown EM, Hebert SC. Localization of the extracellular Ca2+/polyvalent cation-sensing protein in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F611–F622, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satoh T, Numakawa T, Abiru Y, Yamagata T, Ishikawa Y, Enokido Y, Hatanaka H. Production of reactive oxygen species and release of L-glutamate during superoxide anion-induced cell death of cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurochem 70: 316–324, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70010316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Servais H, Van Der Smissen P, Thirion G, Van der Essen G, Van Bambeke F, Tulkens PM, Mingeot-Leclercq MP. Gentamicin-induced apoptosis in LLC-PK1 cells: involvement of lysosomes and mitochondria. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 206: 321–333, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shino Y, Itoh Y, Kubota T, Yano T, Sendo T, Oishi R. Role of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase in cisplatin-induced injury in LLC-PK1 cells. Free Radic Biol Med 35: 966–977, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soboloff J, Spassova M, Hewavitharana T, He LP, Luncsford P, Xu W, Venkatachalam K, van Rossum D, Patterson RL, Gill DL. TRPC channels: integrators of multiple cellular signals. Handb Exp Pharmacol 179: 575–591, 2007. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun YH, Liu MN, Li H, Shi S, Zhao YJ, Wang R, Xu CQ. Calcium-sensing receptor induces rat neonatal ventricular cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 350: 942–948, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan RJ, Zhou D, Liu Y. Signaling crosstalk between tubular epithelial cells and interstitial fibroblasts after kidney injury. Kidney Dis (Basel) 2: 136–144, 2016. doi: 10.1159/000446336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teijido O, Dejean L. Upregulation of Bcl2 inhibits apoptosis-driven BAX insertion but favors BAX relocalization in mitochondria. FEBS Lett 584: 3305–3310, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.ten Cate MG, Omerović M, Oshovsky GV, Crego-Calama M, Reinhoudt DN. Self-assembly and stability of double rosette nanostructures with biological functionalities. Org Biomol Chem 3: 3727–3733, 2005. doi: 10.1039/b508449k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe J, Takiyama Y, Honjyo J, Makino Y, Fujita Y, Tateno M, Haneda M. Role of IGFBP7 in diabetic nephropathy: TGF-β1 induces IGFBP7 via Smad2/4 in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. PLoS One 11: e0150897, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiegele G, Brandis M, Zimmerhackl LB. Apoptosis and necrosis during ischaemia in renal tubular cells (LLC-PK1 and MDCK). Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 1158–1167, 1998. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.5.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu CT, Weng TI, Chen LP, Chiang CK, Liu SH. Involvement of caspase-12-dependent apoptotic pathway in ionic radiocontrast urografin-induced renal tubular cell injury. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 266: 167–175, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang W, Wang Y, Roberge JY, Ma Z, Liu Y, Michael Lawrence R, Rotella DP, Seethala R, Feyen JH, Dickson JK Jr. Discovery and structure-activity relationships of 2-benzylpyrrolidine-substituted aryloxypropanols as calcium-sensing receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 15: 1225–1228, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu CC, Chou CT, Sun TK, Liang WZ, Cheng JS, Chang HT, Wang JL, Tseng HW, Kuo CC, Chen FA, Kuo DH, Shieh P, Jan CR. Effect of melamine on [Ca(2+)]i and viability in PC3 human prostate cancer cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 38: 800–806, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zimmerhackl LB, Mesa H, Krämer F, Kölmel C, Wiegele G, Brandis M. Tubular toxicity of cyclosporine A and the influence of endothelin-1 in renal cell culture models (LLC-PK1 and MDCK). Pediatr Nephrol 11: 778–783, 1997. doi: 10.1007/s004670050389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]