Although the role of wall shear stress (WSS) has been well investigated, the role of circumferential wall stresses (CWS) has not been well studied in provisional stenting with and without final kissing balloon. Both fluid and solids mechanics need to be evaluated when considering various stenting techniques at bifurcations. An integrative index of bifurcation mechanics is the stress ratio that considers both CWS and WSS.

Keywords: bifurcation provisional stenting, balloon dilatation, intramural stress, adverse events, target-vessel revascularization

Abstract

In-stent restenosis (ISR) and stent thrombosis remain clinically significant problems for bifurcations. Although the role of wall shear stress (WSS) has been well investigated, the role of circumferential wall stresses (CWS) has not been well studied in provisional stenting with and without final kissing balloon (FKB). We hypothesized that the perturbation of CWS at the SB in provisional stenting and balloon dilatation is an important factor in addition to WSS, and, hence, may affect restenosis rates (i.e., higher CWS correlates with higher restenosis). To test this hypothesis, we developed computational models of stent, FKB at bifurcation, and finite element simulations that considered both fluid and solid mechanics of the vessel wall. We computed the stress ratio (CWS/WSS) to show potential correlation with restenosis in clinical studies (i.e., higher stress ratio correlates with higher restenosis). Our simulation results show that stenting in the main branch (MB) increases the maximum CWS in the side branch (SB) and, hence, yields a higher stress ratio in the SB, as compared with the MB. FKB dilatation decreases the CWS and increases WSS, which collectively lowers the stress ratio in the SB. The changes of stress ratio were correlated positively with clinical data in provisional stenting and FKB. Both fluid and solid mechanics need to be evaluated when considering various stenting techniques at bifurcations, as solid stresses also play an important role in clinical outcome. An integrative index of bifurcation mechanics is the stress ratio that considers both CWS and WSS.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Although the role of wall shear stress (WSS) has been well investigated, the role of circumferential wall stresses (CWS) has not been well studied in provisional stenting with and without final kissing balloon. Both fluid and solid mechanics need to be evaluated when considering various stenting techniques at bifurcations. An integrative index of bifurcation mechanics is the stress ratio that considers both CWS and WSS.

bifurcations are among the most frequently encountered coronary complexities in everyday interventional practice. Risks of in-stent restenosis (ISR) and late-stent thrombosis remain as complications, especially for bifurcation lesions. Provisional stenting (PS) is currently the default approach in bifurcation stenting. The PS strategy first places a stent in the main branch, and a then second stent in the SB if necessary. Using the PS approach yields acceptable ISR rates in the MB, but the clinical results for the SB is not satisfactory with an ISR rate of ~15%, even for the drug-eluting stent (DES) (11). Stent struts may affect the flow, as well as the intramural stress at the bifurcation. Clinical findings indicate that side branch (SB) has a much higher restenosis rate than that of the main branch (MB) in provisional stenting (16). Postdilatation with final kissing balloon (FKB) has shown clinical benefits for dual stenting (11). Additionally, short-term and long-term clinical data suggest that FKB lowered SB restenosis rate (24). In the COBIS II trial, the FKB group had a lower incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), and target lesion revascularization in both vessels than in the non-FKB group (29).

Computational simulation is a very useful tool to evaluate the mechanical performance of stents. Compared with experimental studies, computational study allows prediction of the stenting procedure’s effects in lieu of expensive and time-consuming processes of making a device prototype and in vivo testing. Simulations also allow virtual testing of an intervention procedure for patients, or “virtual surgery”. Although the fluid shear stresses have been well investigated in bifurcations, the same is not true of intramural stresses (1, 4–6, 13). The objective of this study is to understand the role of fluid and solid mechanical disturbances caused by provisional stenting and FKB dilatation on ISR. We hypothesized that the perturbation of intramural stresses (i.e., circumferential wall stress, CWS) at the SB in provisional stenting and FKB dilatation is important in addition to the fluid wall shear stresses (WSS) and, hence, affect restenosis rates (i.e., higher CWS correlates with higher restenosis). To test this hypothesis, we developed computational models of stent at bifurcation and finite element simulations. The models were used to predict both CWS and WSS, and consequently, the stress ratio (CWS/WSS) as a potential biomechanical marker of ISR. We qualitatively compared the simulation results with relevant coronary interventional clinical data to evaluate potential correlations.

METHODS

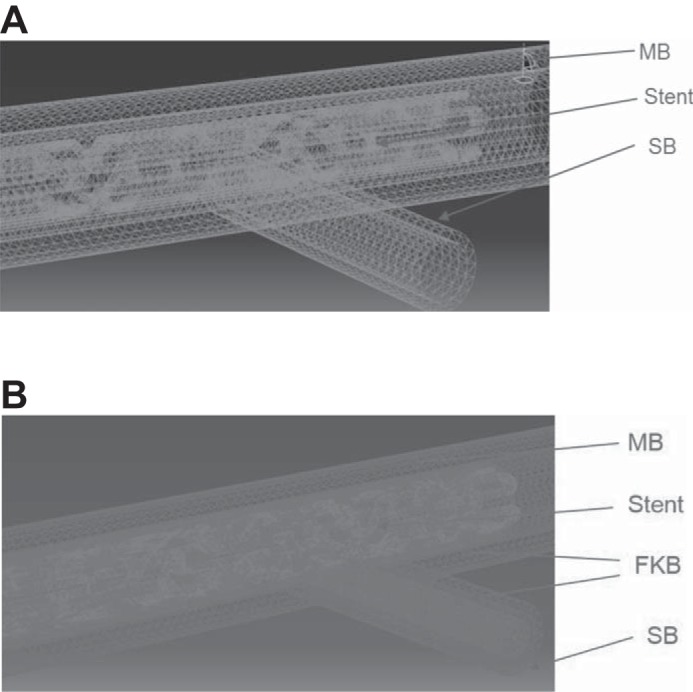

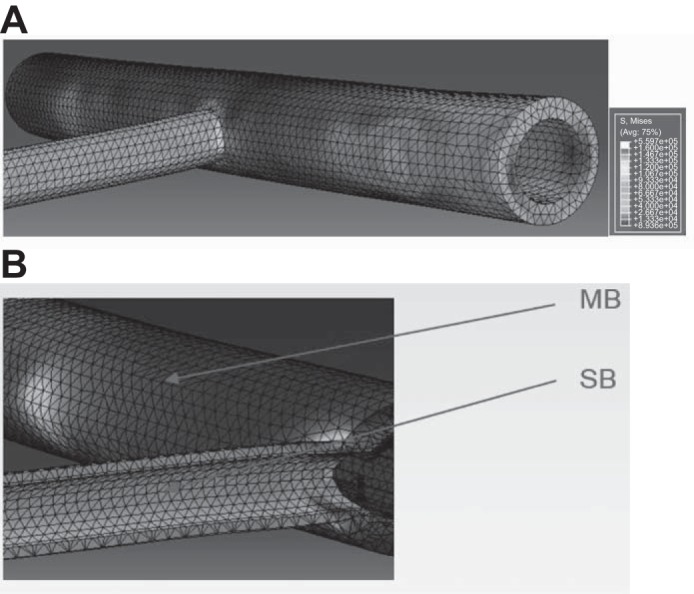

Three-dimensional computational models of stent, FKB balloons, and bifurcation were created in CREO (Pro/Engineer, Needham, MA), which is a computer-assisted design package. The models were then interfaced, meshed, and solved in Abaqus (Johnston, RI) (Fig. 1). The Abaqus implicit solver was applied because it has a stable contact algorithm. FKB consisted of balloon in both SB and MB, immediately following provisional stenting to ensure that the branches were dilated. The relative positions of stent, FKB, and the bifurcation are indicated in the figure (Fig. 1B). The meshes consisted of structured and refined elements to ensure convergence and accuracy of simulation results (Fig. 1, A and B).

Fig. 1.

The highly structured and refined mesh of stent, first kissing balloon (FKB) and vessel bifurcation: with provisional stenting (A) and FKB (B). The relative positions of stent, FKB balloon in both main branch (MB) and side branch (SB), and the bifurcation are indicated in the figure.

The stent struts interact and deform the vessel wall by the augmented Lagrangian contact algorithm. Penetration between the stent, FKB, and vessel elements was not allowed by the contact algorithm. If penetration was detected, the overlapping elements were returned to their positions at the previous time step. A large deformation analysis was performed and solved using a Newton-Raphson's method. To model interactions between specific model portions, contact surfaces were introduced. The bifurcation was constrained in the proximal and distal sections to prevent rotations.

For blood, a non-Newtonian Carreau model was used to account for the shear thinning behavior of blood. The model has been known to accurately describe the behavior of red blood cell suspensions, and the viscosity matched closely with experimental measurements (5, 7). The density of the blood was taken as 1,060 kg/m3. The blood was modeled as incompressible with pulsatile flow based on human left coronary artery velocity measurements applied at the inlet of the vessel (7, 9). For the outlet of the vessels, a traction-free boundary condition was imposed (5, 7). At the wall interface, no slip was assumed between blood and the endothelium, and the vessel wall was considered to be impermeable. The flow was assumed to be nonturbulent.

To evaluate both the solid and fluid effects, we used a stress ratio defined as solid CWS/fluid WSS. This stress ratio was previously validated for evaluation of mechanical disturbances caused by a coronary artery stent (8). It was found that the disturbances in solid stress and fluid shear act in synergy, since the combination of these two forces due to stent radial stretch and strut flow disturbances resulted in more highly significant correlations to intimal hyperplasia (IH) than each individual effect (8).

RESULTS

The simulation results were independent of the computational time steps, as the resulting solid and fluid stress patterns and magnitudes were very similar for various time steps. The Reynolds number for the computational models was ~110. This is an order of magnitude smaller than the Reynolds number for transition to turbulence (2,300–4,000) and, hence, justifies the current nonturbulent models. The Womersley number was ~2.1, which indicates that the importance of flow inertia force was greater than viscous forces.

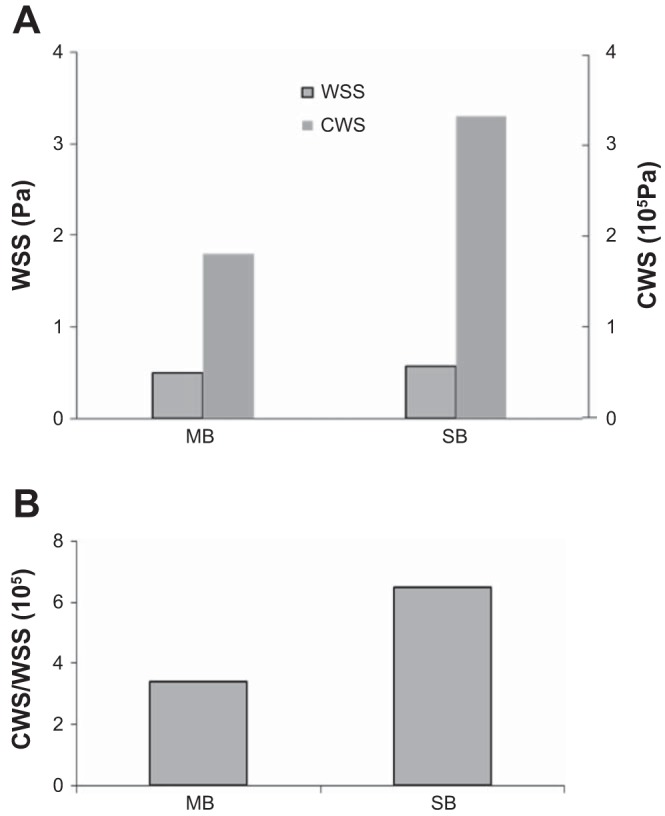

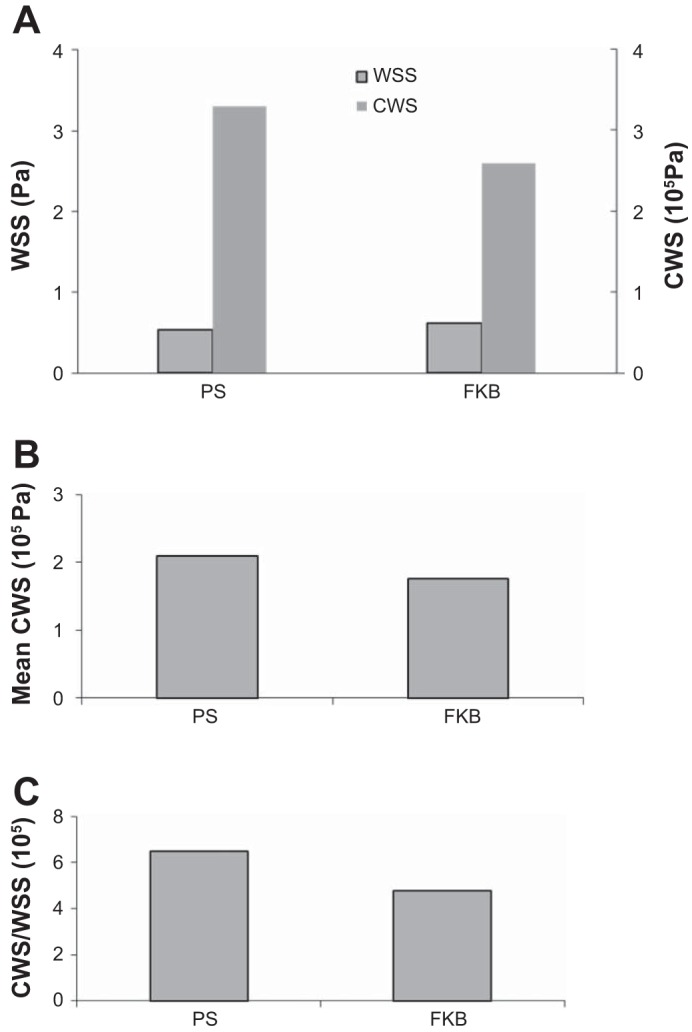

Stenting in MB resulted in nearly double the maximum solid wall stress in SB. The difference in fluid WSS was less pronounced, suggesting in PS, the difference was more due to the solid mechanics (Fig. 2A). The simulations predict the SB to have nearly twice as large a stress ratio as the MB (6.4 × 105 vs. 3.5 × 105) (Fig. 2B). The maximum CWS was higher in PS compared with FKB, even though the mean CWS was not significantly different (Fig. 3). With FKB, the maximum solid CWS decreased, while the fluid WSS increased in the SB. Overall, FKB lowered the stress ratio in the SB (4.8 × 105 vs. 6.4 × 105), as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

A: stenting in MB resulted in nearly double the maximum solid stress in SB. The difference in fluid wall shear stress (WSS) was less pronounced, suggesting in this case, the difference was more due to the solid mechanics. B: simulations predict the SB to have a nearly twice as large stress ratio [circumferential wall stress (CWW)/WSS] as the MB.

Fig. 3.

A: provisional stenting (PS) resulted in higher maximum solid stress in SB than FKB. Additionally, PS resulted in lower fluid WSS in SB. B: FKB dilatation reduced the maximum CWS compared with PS, even though the mean CWS were not as different. C: the simulations predicted an ~40% larger stress ratio for provisional stenting than FKB.

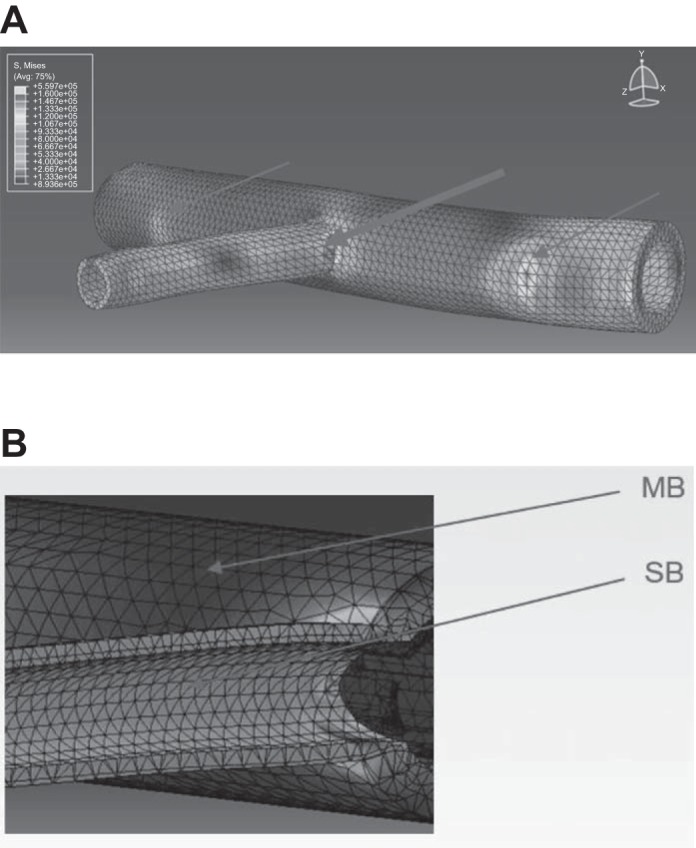

For provisional stenting, the stress distribution shows stress concentration at the SB, near the intersection of branches, as indicated by a large arrow in Fig. 4A. Additionally, there were also minor stress concentrations (as indicated by small arrows) at the ends of the stent. The stress distribution at the SB was smoother and nearly uniform after FKB (Fig. 5). Less stress concentration is observed in the SB. The fluid WSS distributions in the case of provisional stenting and after FKB are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 4.

A: for provisional stenting, the stress distribution shows stress concentration at the SB, near the carina (indicated by thick arrow). Additionally, at the ends of stent, there were also minor stress concentrations (thin arrows). B: detailed view of the local stress concentrations in the case of PS. Localized stress concentrations are observed at the side branch (SB), near the intersection with the main branch (MB).

Fig. 5.

A: stress distribution on the side branch (SB) was smooth and nearly uniform after FKB. B: detailed view of the local stress distributions after FKB. Less stress concentration is observed and stress distribution was smooth in the SB. MB, main branch.

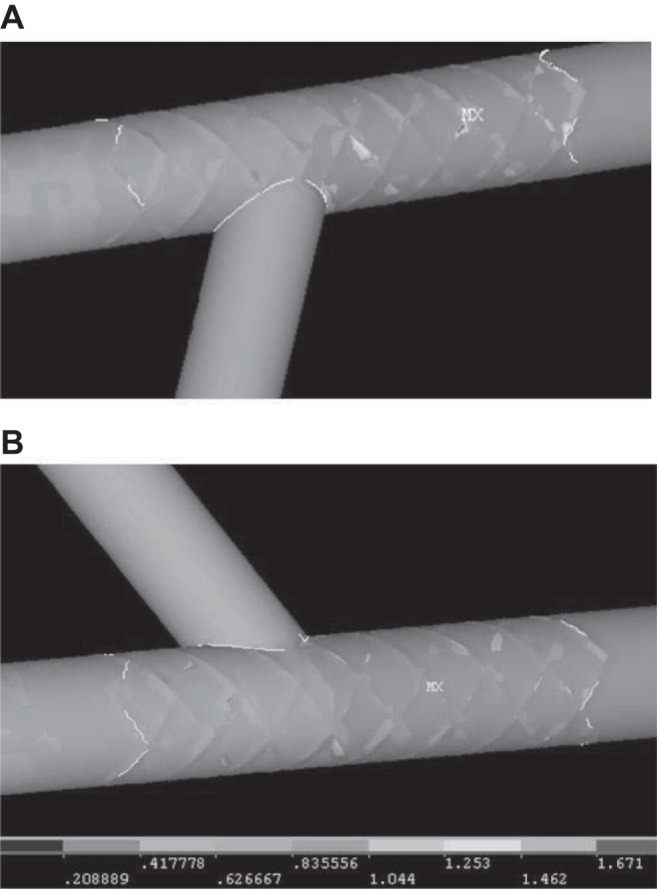

Fig. 6.

The fluid WSS distributions in the cases of provisional stenting (A) and after FKB (units in pascals) (B). The WSS at SB is slightly higher after FKB.

DISCUSSION

This study found that the increase in intramural stresses is higher at SB than MB during provisional stenting. The simulations predict the SB to have a larger stress ratio than the MB. Higher restenosis rate at SB was found clinically. The restenosis rate at SB was 8.3%, while much lower at 2.8% for the MB. This is consistent with simulation findings that the SB has a larger stress ratio than the MB (Fig. 2). Additionally, in the case of FKB, the stresses decreased, while the WSS increased. Overall, the stress ratio decreased (Fig. 3). These findings are consistent with clinical findings that higher restenosis rates (15% long term, 5.6% short term) were in the case of PS, while significantly lower (8% long term, 2.8% short term) for FKB (16, 24). Furthermore, the FKB group had a lower incidence of MACE and target lesion revascularization in both vessels than in the non-FKB group in the COBIS II trial (29). The maximum CWS was higher in PS as compared with FKB, even though the mean CWS was not dramatically different (Fig. 3B). This is likely due to the hard metal struts having small contact areas with the vessel wall, hence, affecting the maximum stresses more significantly, whereas the balloon has a smooth surface and larger contact area. Both fluid and solid mechanics need to be evaluated when considering various interventional techniques at bifurcations.

Studies have found that the disturbances in solid stress and fluid shear act synergistically, since the combination of these two forces due to stent radial stretch and strut flow disturbances has been found to result in more highly significant correlations to IH than each individual effect (7, 8). Intramural stress is known to be a stimulus for tissue remodeling; i.e., vessels develop hyperplasia to reduce wall stresses. Higher restenosis rate up to 15% in the SB was reported in a clinical trial using DES (11).

The stress distribution shows stress concentration at the SB, near the intersection of branches (Fig. 4A). Additionally, the minor stress concentrations at the edges of stent may contribute to the edge restenosis phenomenon (Fig. 4A).

Provisional stenting is the current default approach for treating bifurcations, as clinical data comparing PS with double stenting found that dual stents did not offer significant advantage (2, 23). FKB has been shown to improve clinical outcome following PS (19). In the Nordic III bifurcation trial, nearly 500 patients were randomized into FKB and non-FKB groups, and it was found at long-term follow-up, FKB significantly reduced SB restenosis rate from 15.4% to 7.9%, P < 0.05. It may be inferred that SB balloon dilatation is better than stenting of the SB, as in the dual-stent approach. Dual stents lower fluid WSS in the SB, as the struts disrupt smooth WSS distribution, which also increases WSS gradient (5). Flow stagnations can also occur at malapposed struts due to suboptimal stent deployment (5, 6).

For bifurcations with certain diameter ratios and angles, the optimal intervention technique may vary, especially where the plaque shift, resulting from stenting the MB, may cause severe stenosis in the SB. The effects of SB balloon are not dramatic on the fluid WSS, as there is no plaque at the carina in the current model. Plaque at the carina may lead to carina shift during FKB, which reduces flow to the SB. Carina shift is more frequent in thin carina in bifurcation with acute angle (22). As carina is most frequently free of atheroma, plaque shift stems from the proximal main vessel (28). Plaque shift from the proximal vessel, associated with carina shift, may occlude the SB (18). The clarification of these issues requires a systemic computational analysis to investigate the effects of various interventional techniques on the solid stress and fluid shear. Longer-term clinical study on stent thrombosis is also needed when considering the optimal intervention techniques, as bifurcations are predictive of very late-stent thrombosis after DES implantation (3, 17).

In line with our previously published study (8), wall stress decreases and shear stress increases (hence, the stress ratio decreases) result in less intimal hyperplasia (8). Therefore, this is expected to lead to less adverse biology responses. Normal arteries experience shear stresses in the range of 0.8 to 1.5 Pa (10, 12, 21). Studies found that fluid shear has an inverse relation with intimal hyperplasia (25, 26). Therefore, higher fluid shear leads to less IH. As for wall stress, the physiological range is ~100 kPa; thus, the stress level after stenting is significantly higher than physiological value and likely to stimulate smooth muscle cell proliferation and IH development. These reported physiological values of wall shear stress and circumferential stress lead to a stress ratio of 0.67 to 1.2 × 105, which is smaller than values obtained with the stent in the vessel.

It has been proposed that the function of vascular remodeling is to restore changes in stresses to their natural physiological state (14). The physical principle that governs the growth and remodeling of the vessel wall is to restore the homeostatic mechanical state (14, 15). Therefore, the closer the stress and shear levels toward the physiological level, the less adverse remodeling and IH growth. The SB dilatation results in wall stress decrease from 330 to 260 kPa, and shear stress increases from 0.5 to 0.6 Pa. These are biologically meaningful and consistent with clinical data (24, 29).

Ideally, the vessel segment modeled should be much longer than the stented portion. As the modeled vessel is proximal in the left coronary tree, the length there is limited. The deformations and stresses are influenced by the surrounding tissue. As the proximal part of the left coronary is only partially embedded by cardiac tissue, the effect is expected to be less than completely embedded vessels. It should be noted that FKB may cause additional endothelial damage in the SB. Endothelial damage is known to have implications on thrombosis and atherogenesis (20). Bifurcation geometries affect the local biomechanics. The main vessel is modeled as cylindrical geometry. Future development can include patient-specific geometries segmented from clinical imaging, such as high-resolution intravascular ultrasound, angiogram, and OCT (27). This will make the device simulations specific to the patient, which may aid the preoperative surgical planning.

Conclusion.

The simulations of provisional stenting and balloon dilatation predicted the solid/fluid stress ratios, which correlated with clinical trials data. Both fluid and solids mechanics need to be evaluated when considering various intervention techniques at coronary or carotid bifurcations.

GRANTS

This research was supported in part by the National Institute of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-117990.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.Y.C. and G.S.K. conceived and designed research; H.Y.C. performed experiments; H.Y.C., K.A.-S., Y.L., and G.S.K. analyzed data; H.Y.C., K.A.-S., Y.L., and G.S.K. interpreted results of experiments; H.Y.C. prepared figures; H.Y.C. drafted manuscript; H.Y.C., K.A.-S., Y.L., and G.S.K. edited and revised manuscript; H.Y.C., K.A.-S., Y.L., and G.S.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antoniadis AP, Giannopoulos AA, Wentzel JJ, Joner M, Giannoglou GD, Virmani R, Chatzizisis YS. Impact of local flow haemodynamics on atherosclerosis in coronary artery bifurcations. EuroIntervention 11, Suppl V: V18–V22, 2015. doi: 10.4244/EIJV11SVA4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assali AR, Assa HV, Ben-Dor I, Teplitsky I, Solodky A, Brosh D, Fuchs S, Kornowski R. Drug-eluting stents in bifurcation lesions: to stent one branch or both? Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 68: 891–896, 2006. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camenzind E, Steg PG, Wijns W. Stent thrombosis late after implantation of first-generation drug-eluting stents: a cause for concern. Circulation 115: 1440–1455, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, Edelman ER, Feldman CL, Stone PH. Role of endothelial shear stress in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling: molecular, cellular, and vascular behavior. J Am Coll Cardiol 49: 2379–2393, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen HY, Koo BK, Kassab GS. Impact of bifurcation dual stenting on endothelial shear stress. J Appl Physiol (1985) 119: 627–632, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00082.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen HY, Koo BK, Bhatt DL, Kassab GS. Impact of stent mis-sizing and mis-positioning on coronary fluid wall shear and intramural stress. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 285–292, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00264.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen HY, Moussa ID, Davidson C, Kassab GS. Impact of main branch stenting on endothelial shear stress: role of side branch diameter, angle and lesion. J R Soc Interface 9:1187–1193, 2012. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen HY, Sinha AK, Choy JS, Zheng H, Sturek M, Bigelow B, Bhatt DL, Kassab GS. Mis-sizing of stent promotes intimal hyperplasia: impact of endothelial shear and intramural stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H2254–H2263, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00240.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen HY, Kassab GS. Computational modeling of coronary stents. In: Computational Biomechanics, edited by Mofrad MR and Guilak FS. New York: Springer, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chien S, Li S, Shyy YJ. Effects of mechanical forces on signal transduction and gene expression in endothelial cells. Hypertension 31: 162–169, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.31.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombo A, Bramucci E, Saccà S, Violini R, Lettieri C, Zanini R, Sheiban I, Paloscia L, Grube E, Schofer J, Bolognese L, Orlandi M, Niccoli G, Latib A, Airoldi F. Randomized study of the crush technique versus provisional side-branch stenting in true coronary bifurcations: the CACTUS (Coronary Bifurcations: Application of the Crushing Technique Using Sirolimus-Eluting Stents) Study. Circulation 119: 71–78, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies PF. Endothelial mechanisms of flow-mediated athero-protection and susceptibility. Circ Res 101: 10–12, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giannoglou GD, Antoniadis AP, Koskinas KC, Chatzizisis YS. Flow and atherosclerosis in coronary bifurcations. EuroIntervention 6, Suppl J: J16–J23, 2010. doi: 10.4244/EIJV6SUPJA4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassab GS. Biomechanics of the cardiovascular system: the aorta as an illustratory example. J R Soc Interface 3: 719–740, 2006. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kassab GS. Mechanical homeostasis of cardiovascular tissue. In: Bioengineering in Cell and Tissue Research, edited by Artmann G, Shu C. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 2008. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75409-1_15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YH, Lee JH, Roh JH, Ahn JM, Yoon SH, Park DW, Lee JY, Yun SC, Kang SJ, Lee SW, Lee CW, Seung KB, Shin WY, Lee NH, Lee BK, Lee SG, Nam CW, Yoon J, Yang JY, Hyon MS, Lee K, Jang JS, Kim HS, Park SW, Park SJ. Randomized comparisons between different stenting approaches for bifurcation coronary lesions with or without side branch stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 8: 550–560, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koo BK, Park KW, Kang HJ, Cho YS, Chung WY, Youn TJ, Chae IH, Choi DJ, Tahk SJ, Oh BH, Park YB, Kim HS. Physiological evaluation of the provisional side-branch intervention strategy for bifurcation lesions using fractional flow reserve. Eur Heart J 29: 726–732, 2008. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JM, Hahn JY, Kang J, Park KW, Chun WJ, Rha SW, Yu CW, Jeong JO, Jeong MH, Yoon JH, Jang Y, Tahk SJ, Gwon HC, Koo BK, Kim HS. Differential prognostic effect between first- and second-generation drug-eluting stents in coronary bifurcation lesions: patient-level analysis of the Korean bifurcation pooled cohorts. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 8: 1318–1331, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefèvre T, Louvard Y, Morice MC, Dumas P, Loubeyre C, Benslimane A, Premchand RK, Guillard N, Piéchaud JF. Stenting of bifurcation lesions: classification, treatments, and results. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 49: 274–283, 2000. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim SY, Jeong MH, Hong SJ, Lim DS, Moon JY, Hong YJ, Kim JH, Ahn Y, Kang JC. Inflammation and delayed endothelization with overlapping drug-eluting stents in a porcine model of in-stent restenosis. Circ J 72: 463–468, 2008. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. JAMA 282: 2035–2042, 1999. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medina A, Suárez de Lezo J, Pan M. [A new classification of coronary bifurcation lesions]. Rev Esp Cardiol 59: 183, 2006. doi: 10.1157/13084649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niccoli G, Ferrante G, Porto I, Burzotta F, Leone AM, Mongiardo R, Mazzari MA, Trani C, Rebuzzi AG, Crea F. Coronary bifurcation lesions: to stent one branch or both? A meta-analysis of patients treated with drug eluting stents. Int J Cardiol 139: 80–91, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niemelä M, Kervinen K, Erglis A, Holm NR, Maeng M, Christiansen EH, Kumsars I, Jegere S, Dombrovskis A, Gunnes P, Stavnes S, Steigen TK, Trovik T, Eskola M, Vikman S, Romppanen H, Mäkikallio T, Hansen KN, Thayssen P, Aberge L, Jensen LO, Hervold A, Airaksinen J, Pietilä M, Frobert O, Kellerth T, Ravkilde J, Aarøe J, Jensen JS, Helqvist S, Sjögren I, James S, Miettinen H, Lassen JF, Thuesen L; Nordic-Baltic PCI Study Group . Randomized comparison of final kissing balloon dilatation versus no final kissing balloon dilatation in patients with coronary bifurcation lesions treated with main vessel stenting: the Nordic-Baltic Bifurcation Study III. Circulation 123: 79–86, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.966879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedersen EM, Oyre S, Agerbaek M, Kristensen IB, Ringgaard S, Boesiger P, Paaske WP. Distribution of early atherosclerotic lesions in the human abdominal aorta correlates with wall shear stresses measured in vivo. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 18: 328–333, 1999. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.1999.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen EM, Agerbæk M, Kristensen IB, Yoganathan AP. Wall shear stress and early atherosclerotic lesions in the abdominal aorta in young adults. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 13: 443–451, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S1078-5884(97)80171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenekecioglu E, Albuquerque FN, Sotomi Y, Zeng Y, Suwannasom P, Tateishi H, Cavalcante R, Ishibashi Y, Nakatani S, Abdelghani M, Dijkstra J, Bourantas C, Collet C, Karanasos A, Radu M, Wang A, Muramatsu T, Landmesser U, Okamura T, Regar E, Räber L, Guagliumi G, Pyo RT, Onuma Y, Serruys PW. Intracoronary optical coherence tomography: Clinical and research applications and intravascular imaging software overview. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 89: 679–689, 2017. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yazdani SK, Vorpahl M, Ladich E, Virmani R. Pathology and vulnerability of atherosclerotic plaque: identification, treatment options, and individual patient differences for prevention of stroke. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 12: 297–314, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s11936-010-0074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu CW, Yang JH, Song YB, Hahn JY, Choi SH, Choi JH, Lee HJ, Oh JH, Koo BK, Rha SW, Jeong JO, Jeong MH, Yoon JH, Jang Y, Tahk SJ, Kim HS, Gwon HC. Long-term clinical outcomes of final kissing ballooning in coronary bifurcation lesions treated with the 1-stent technique: results from the COBIS II registry (Korean coronary bifurcation stenting registry). JACC Cardiovasc Interv 8: 1297–1307, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]