Here, we demonstrate that 1) stimulation of cAMP production deactivates ischemia-reperfusion-induced hyperpermeability in muscle and endothelial cells; 2) VEGF mRNA expression is not enhanced by brief ischemia, suggesting that VEGF mechanisms do not activate immediate postischemic hyperpermeability; and 3) deactivation mechanisms operate via cAMP-exchange protein activated by cAMP 1-Rap1 to restore integrity of the endothelial barrier.

Keywords: ischemia-reperfusion; inflammation; capillary permeability; endothelium, cAMP; Rap1; exchange protein activated by cAMP

Abstract

Approaches to reduce excessive edema due to the microvascular hyperpermeability that occurs during ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) are needed to prevent muscle compartment syndrome. We tested the hypothesis that cAMP-activated mechanisms actively restore barrier integrity in postischemic striated muscle. We found, using I/R in intact muscles and hypoxia-reoxygenation (H/R, an I/R mimic) in human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs), that hyperpermeability can be deactivated by increasing cAMP levels through application of forskolin. This effect was seen whether or not the hyperpermeability was accompanied by increased mRNA expression of VEGF, which occurred only after 4 h of ischemia. We found that cAMP increases in HMVECs after H/R, suggesting that cAMP-mediated restoration of barrier function is a physiological mechanism. We explored the mechanisms underlying this effect of cAMP. We found that exchange protein activated by cAMP 1 (Epac1), a downstream effector of cAMP that stimulates Rap1 to enhance cell adhesion, was activated only at or after reoxygenation. Thus, when Rap1 was depleted by small interfering RNA, H/R-induced hyperpermeability persisted even when forskolin was applied. We demonstrate that 1) VEGF mRNA expression is not involved in hyperpermeability after brief ischemia, 2) elevation of cAMP concentration at reperfusion deactivates hyperpermeability, and 3) cAMP activates the Epac1-Rap1 pathway to restore normal microvascular permeability. Our data support the novel concepts that 1) different hyperpermeability mechanisms operate after brief and prolonged ischemia and 2) cAMP concentration elevation during reperfusion contributes to deactivation of I/R-induced hyperpermeability through the Epac-Rap1 pathway. Endothelial cAMP management at reperfusion may be therapeutic in I/R injury.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Here, we demonstrate that 1) stimulation of cAMP production deactivates ischemia-reperfusion-induced hyperpermeability in muscle and endothelial cells; 2) VEGF mRNA expression is not enhanced by brief ischemia, suggesting that VEGF mechanisms do not activate immediate postischemic hyperpermeability; and 3) deactivation mechanisms operate via cAMP-exchange protein activated by cAMP 1-Rap1 to restore integrity of the endothelial barrier.

ischemia, a deficient supply of blood to an organ or limb, can be caused by several factors that disrupt normal circulation, including vascular surgery and organ transplantation. The goal of clinicians in treating ischemia is to reestablish blood flow (reperfusion) in a timely manner to preserve organ function. A major complication of reperfusion after ischemia is ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, which is characterized by a strong inflammatory response and places ischemic tissue at risk for further damage.

I/R-induced inflammation is characterized by a sustained increase in microvascular permeability (hyperpermeability) to macromolecules. We have demonstrated that I/R and agonist-induced inflammation increase microvascular hyperpermeability mainly at sites in postcapillary venules (2, 5, 10, 17, 30, 32, 50, 51). During acute inflammation, hyperpermeability leads to edema and promotes extravasation of immune cells, thus facilitating efficient clearance of cellular debris and repair of damaged tissue. However, a sustained hyperpermeability response can have deleterious effects on microvascular integrity, leading to endothelial dysfunction and chronic inflammation. Human skeletal muscle deprived of circulation for up to 3 h shows injury to the microvasculature within 30 min after reperfusion (8).

Ischemia causes tissue hypoxia, i.e., a decrease in O2 tension below the levels that can support oxidative cell metabolism. Hypoxic or injured tissues release VEGF as a repair mechanism to enhance nutrient delivery by increasing blood flow and microvascular permeability and by promoting angiogenesis (53). In addition, hypoxia is associated with impaired endothelial barrier function due to decreased adenylate cyclase activity and intracellular cAMP levels, which may contribute to increased vascular permeability (24, 40). Our laboratory has reported that iloprost, a prostacyclin analog, attenuates the hyperpermeability response caused by I/R in striated muscle (9). Upon binding to receptors on endothelial cells (ECs), prostacyclin and iloprost activate cAMP-dependent pathways, which may lead to the restoration of vascular integrity (6, 7). The classical paradigm of cAMP signaling follows the activation of PKA, leading to the dephosphorylation of myosin light chains and reduced actin/myosin contraction. However, direct inhibition of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) or Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) failed to block platelet-activating factor (PAF)-stimulated permeability in rat mesentery microvessels (1, 49), suggesting that PKA-dependent cAMP signaling is insufficient on its own to attenuate hyperpermeability and perhaps that another cAMP signaling pathway is responsible.

Exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac) is a cAMP-sensitive guanine-nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that activates the small GTPase Rap1 (11). Activated Rap1 interacts with the Rac-GEFs Vav2 and Tiam1 and promotes actin rearrangement and cell-cell adhesion (12). This is a potential pathway by which increased cAMP may restore the microvascular permeability barrier. Managing cAMP levels in ECs seems to be a viable target for microvascular barrier restoration, but current mechanistic understanding of cAMP signaling in I/R-induced barrier dysfunction is limited. In this work, we explored the time course of cAMP levels in the restoration of the microvascular barrier in vivo and explored the mechanisms of cAMP action on hyperpermeability in human microvascular ECs (HMVECs) in culture. Our findings support the concept that the cAMP-Epac-Rap1 pathway is an important endothelial barrier-enhancing mechanism in the context of I/R-induced inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

We used male Golden Syrian hamsters (100–150 g) for the intravital microscopy assessment of microvascular permeability and male Sprague-Dawley rats (150–290 g) for the experiments designed to assess the role of VEGF in I/R-induced hyperpermeability. Animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (hamsters: 50 mg/kg ip and rats: 60 mg/kg ip). Experimental protocols involving animal utilization were reviewed and approved by the New Jersey Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animals were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited animal facility at Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School.

Hamster cremaster muscle preparation.

We prepared the hamster cremaster muscle for intravital microscopy observation as previously described (10, 32, 50–52). Each cremaster preparation served as control and I/R subject. After obtaining control data, we cross clamped the cremasteric artery with an atraumatic vascular clamp to institute ischemia for 30 min. We achieved reperfusion by removing the vascular clamp and observed the preparation for additional 90–120 min. We measured microvascular permeability to FITC-dextran 70 by integrated optical intensity (IOI) (5, 33).

Rat gastrocnemius muscle preparation.

Animals were randomly assigned to control, ischemia, and I/R groups. After anesthesia, we exposed the abdomen, cross clamped the infrarenal aorta, and subsequently closed the abdomen. We instituted ischemia for 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, or 4 h. Animals assigned to ischemia groups were euthanized at the end of the assigned ischemic period. In animals assigned to reperfusion analysis, we released the vascular clamp at the end of ischemia to allow reperfusion for 1 h. After the assigned I/R periods, we euthanized the animals and extracted and snap froze the gastrocnemius muscle (200–450 mg) for biochemical analysis. We performed surgery without infrarenal aortic clamping in control groups. We euthanized the control animals after 5 h to extract and analyze the gastrocnemius muscle.

Chemicals, reagents, and antibodies.

Forskolin and FITC-dextran 70 were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Recombinant VEGF165 was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Rabbit polyclonal anti-Rap1 and anti-hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α were from Millipore (Temecula, CA). The active Rap1 detection kit was from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA). Goat polyclonal anti-vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Small interfering (si)RNA oligonucleotides nontargeting control and Rap1 targeting and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin were from Sigma. Control nontargeting and Epac1 targeting siRNAs were from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

RT-PCR.

We performed RT-PCR according to the manufacturer's instructions in samples from the rat gastrocnemius muscle. We used primers specific for the cDNA reverse transcribed from the mRNA encoding for the VEGF164 isoform. Amplification of the target cDNA was quantified by plotting the target-to-competitor PCR band intensity ratio versus the initial competitor cDNA load for each PCR.

Cell culture.

We used HMVECs of dermal origin (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). We used HMVECs between passages 5 and 7 for experiments.

In vitro models of hypoxia/reoxygenation.

The sequence of hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) is accepted as an adequate model on the basis that the fall in tissue Po2 in ischemia and the rise in tissue Po2 upon reperfusion is a major event for the vascular and parenchymal cellular changes. For all experiments involving determination of proteins by Western blot or enzymatic immunoassays, we used a controlled-atmosphere chamber connected to an OxyCycler C42 unit (BioSpherix, Lacona, NY), which allowed for precise control of O2 concentration in the liquid phase using dissolved O2 sensors (Fig. 1A). For permeability experiments, we used Navicyte vertical diffusion chambers (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA), in which hypoxia was achieved by bubbling a mixture of 95% N2-5% CO2 into the media bathing the ECs and measured by an oxygen-sensitive electrode (Harvard Apparatus; Fig. 1B) while reoxygenation was established by bubbling balanced air (21% O2-5% CO2).

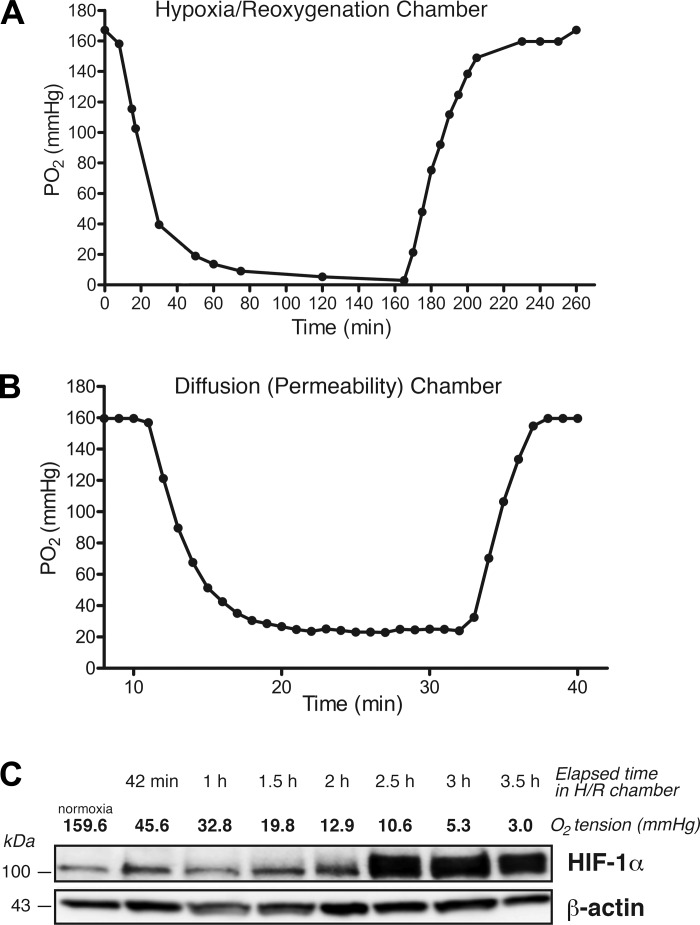

Fig. 1.

Measurement of hypoxia-reoxygenation (H/R) in cultured human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs). The time course of O2 depletion in endothelial cell culture medium was examined in two independent systems. A: controlled atmosphere chamber. O2 content was set to 0.1% for 3.5 h, and dissolved Po2 was measured with a fiber optics probe as a function of time. B: vertical diffusion chamber. Diffusion chambers were filled with culture medium and a 95% N2-5% CO2 mixture was bubbled to establish hypoxia. Dissolved Po2 was registered at 1-min intervals with an oxygen-sensitive electrode. The beginning of hypoxia and of reoxygenation is shown by the respective inflexion points in A and B. C: time course of hypoxia induced hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α in HMVECs (controlled atmosphere chamber). HIF-1 α expression peaked at 150 min of hypoxia (Po2: 10.6 mmHg) and remained elevated after 3.5 h (Po2: 3.0 mmHg). β-Actin served as a loading control.

Postcapillary venular Po2 varies between 33 and 35 mmHg (36), whereas tissue Po2 is ~25 mmHg in skeletal muscle (58). Thus, we set an operational threshold for hypoxia at Po2 < 20 mmHg. As an independent assessment of hypoxia, we evaluated the upregulation of HIF-1α by Western blot analysis in cells cultured in the OxyCycler C42 unit (Fig. 1C). HIF-1α levels peaked at Po2 of 10.6 mmHg and remained elevated and relatively constant despite further decreases in Po2 over time.

Endothelial monolayer permeability.

Permeability measurements were performed as previously described (34, 35, 42, 43, 55). Briefly, HMVECs were seeded on gelatin-coated polycarbonate membranes (pore size: 0.4 μm, Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY) and allowed to form a confluent monolayer. Transport of FITC-dextran 70 across the endothelial monolayer was measured with a Perkin-Elmer LS-55 spectrofluorometer. Permeability coefficients were calculated using Fick’s first law of diffusion.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis were performed according to established protocols. Forty micrograms from each sample of lysed HMVECs were loaded on precast gels and electrophoretically separated. Protein bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence, digitized using the Fujifilm LAS 4000 digital imaging system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) and analyzed with Fujifilm MultiGauge 3.1 software.

Measurement of cAMP.

cAMP measurements were performed using the cAMP Direct Biotrak EIA kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions on confluent HMVEC monolayers seeded on 35-mm dishes.

siRNA-mediated protein knockdown.

HMVECs were seeded on 35-mm dishes and incubated overnight at 37°C. We delivered siRNA using Oligofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) for 4–6 h at 37°C. We stopped transfection by replacing transfection medium with complete medium supplemented to 10–15% FBS. We trypsinized cells 24 h after transfection and seeded them on Snapwell inserts for measurements of permeability to FITC-dextran 70.

Statistical analysis.

All data are shown as means ± SE. We carried out statistical comparisons between two groups using two-tailed Student’s t-test and used one-way ANOVA for comparisons between three or more groups followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test. We accepted differences as significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Ischemic skeletal muscle upregulates VEGF expression after prolonged ischemia.

While the objective of our study was to identify mechanisms that terminate hyperpermeability, it is important to determine the main mechanism that activates hyperpermeability. We have observed that ischemic striated muscles develop hyperpermeability immediately upon the onset of reperfusion, independently of the duration of the ischemic period (9, 23, 50–52). Thus, to determine whether VEGF is the main factor responsible for the induction of hyperpermeability in I/R, we evaluated VEGF mRNA expression and protein synthesis using competitive RT-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively. While there are several VEGF isoforms, we focused on VEGF164 because neuropilin-1, a required step in promoting hyperpermeability via VEGF, binds VEGF164 and does not bind VEGF120 or VEGF188 (37, 41, 54, 56). VEGF164 mRNA expression was unchanged for ischemic periods of 15, 30, and 60 min, whereas it was significantly increased at 4 h of ischemia (Fig. 2A). Restoration of blood flow led to decrease of VEGF164 mRNA expression after 4-h ischemia; however, it remained significantly elevated at the end of the reperfusion period compared with control levels (Fig. 2A). Because upregulation of VEGF mRNA does not necessarily imply increased translation into the peptide, we analyzed VEGF164 peptide by Western blot analysis in gastrocnemius homogenates from rats subjected to either 4-h ischemia alone or 4-h ischemia followed by 1-h reperfusion. While 4-h ischemia significantly upregulated VEGF164 mRNA expression, it did not increase synthesis of the VEGF peptide (Fig. 2, A and C). A representative Western blot of VEGF164 as a function of ischemia and I/R, with actin as loading control, is shown in Fig. 2C.

Fig. 2.

Prolonged ischemia induces VEGF expression in rat skeletal muscle. A: VEGF164 mRNA was significantly upregulated only after 4 h of ischemia relative to a competitor cDNA and remained elevated above control after 1-h reperfusion (*P < 0.05 relative to control). B: VEGF164 peptide expression in control, ischemic, and postischemic muscle was evaluated by Western blot analysis. VEGF peptide levels did not increase during ischemia compared with control. Reperfusion significantly upregulated VEGF164 expression versus control (2.5-fold upregulation; *P < 0.05 compared with control). C: representative Western blot of homogenized rat gastrocnemius muscle showing upregulation of VEGF peptide only after 4 h of ischemia followed by 1 h of reperfusion. β-Actin was used as a loading control. A–C: n = 5 for each group. A and B: means ± SE; one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

We interpret the preceding findings to indicate that 1) VEGF contributes to hyperpermeability only after prolonged ischemia and 2) approaches to counteract edemogenesis should be directed also against mechanisms that act earlier during ischemia.

H/R increases endothelial cAMP concentration.

Exogenous stimuli leading to increases of intracellular cAMP concentration ([cAMP]i) in ECs have been correlated with enhancement of endothelial barrier function (26, 44, 46). However, it is unclear whether or not cAMP concentration changes during I/R or its mimic H/R. To establish the relevance of cAMP as a potential agent to ameliorate I/R-induced vascular damage, we explored the time course of changes in endogenous cAMP triggered by H/R in HMVECs. Baseline cAMP levels remained relatively constant in HMVECs cultured under normoxic conditions (Fig. 3A). We exposed HMVECs to 30 min of hypoxia followed by 1.5 h of reoxygenation and measured [cAMP]i levels. Hypoxia elevated [cAMP]i from ~100 to ~160 fmol/105 cells, but the difference was not statistically significant. [cAMP]i increased significantly as soon as reperfusion started and reached a peak of ~330 fmol/105 cells after 45 min of reoxygenation (Fig. 3A). [cAMP]i declined afterward and approached near baseline levels by 60 min of reperfusion. In separate experiments, we measured total cAMP concentration (intracellular + medium) for 1 h after reperfusion. The time-course results of these measurements (not shown) were similar to those obtained by measuring only [cAMP]i. Thus, it appears that cAMP increases somewhat during hypoxia, but it undergoes a substantial transient increase during reoxygenation before returning to near normal levels.

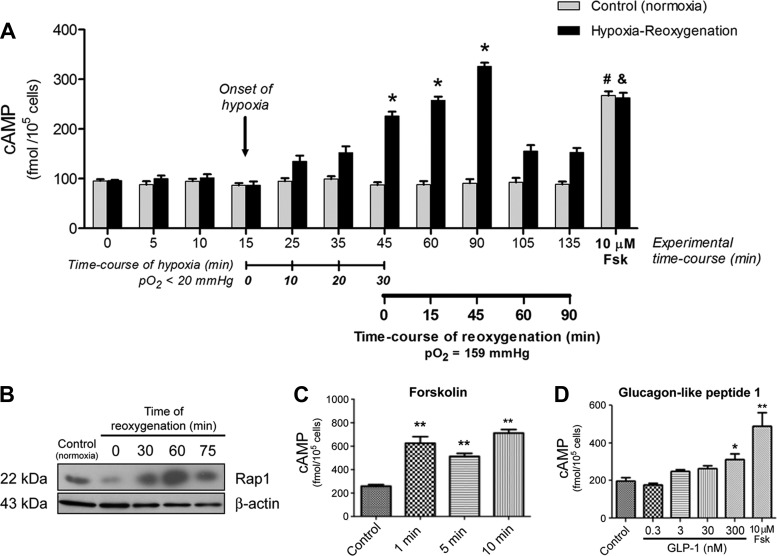

Fig. 3.

H/R increases endothelial cAMP. A: we determined intracellular cAMP levels in HMVEC monolayers under normoxia and throughout H/R. Intracellular cAMP levels remained relatively stable over time in cells exposed to a normoxic atmosphere. Hypoxia elevated but did not significantly increase intracellular cAMP levels. Reoxygenation significantly increased cAMP peaking at 45 min after the onset of reoxygenation. cAMP subsequently declined toward baseline. Data are mean ± SE; n = 5. *P < 0.05 vs. normoxic control; #&P < 0.05 compared with respective samples at 135 min (i.e., 90 min of reoxygenation). B: activation of Rap1 as a function of time after reperfusion. Time 0 (0’) indicates the end of hypoxia. Hypoxia was established by exposing HMVECs to 5% O2 for 30 min. Normoxia [control (Ctr)] and reoxygenation were established with 20% O2. β-Actin served as a loading control; n = 3. C: forskolin (10 µM) increased cAMP. D: cAMP as a function of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) concentration. C and D: n = 5 for each group. Data are means ± SE; n = 5. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, both compared with control. A, C, and D: one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

Since the cAMP concentration increased during reperfusion, we tested whether or not Rap1 also underwent changes due to H/R in HMVCs because Rap1 is the final step in the cAMP-Epac1-Rap1 pathway. Figure 3B shows the results of a representative experiment measuring activated Rap1 (Rap1-GTP) as a function of hypoxia and time after reoxygenation in HMVECs. Hypoxia (5% O2 for 30 min, shown as 0 min of reperfusion) reduced the signal for activated Rap1, whereas reoxygenation showed increased activated Rap1 at 30, 60, and 75 min of reoxygenation. While we did not pursue a time correlate between changes in cAMP concentration and Rap1, the results shown in Fig. 3B provide evidence that a temporal correlation exists.

Increases in cAMP have been reported to reduce endothelial permeability (26, 44, 46). To further explore the ability to reduce hyperpermeability through enhanced cellular cAMP concentration, we tested the capacity of forskolin and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) to increase cAMP in HMVECs. Forskolin is a cell-permeable direct activator of adenylyl cyclase that increases cAMP within 1 min of binding isoform 6 of adenylyl cyclase, which predominates in ECs and is sensitive to forskolin (14)]. The results shown in Fig. 3C confirm that forskolin increased cAMP concentration significantly and that the increase in cAMP concentration was independent of the duration of application at least up to 10 min. The results shown in Fig. 3D demonstrate that 300 nM GLP-1 increased cAMP concentration, whereas lower concentrations failed to enhance cAMP concentration. Figure 3D also shows that 10 µM forskolin was more efficacious than 300 nM GLP-1 in elevating cAMP concentration; thus, further experiments were performed using forskolin at 10 µM (in vitro) or 100 µM (in vivo).

Forskolin-induced increased cAMP concentration deactivates I/R-induced hyperpermeability in the hamster cremaster microcirculation.

The results shown in Fig. 3 demonstrate that H/R influences the time course of endothelial cAMP concentration and support a potential role of enhanced cAMP in the restoration of normal endothelial barrier properties. Because hyperpermeability occurs immediately upon reperfusion in striated muscle (21, 32), it is plausible that the onset of hyperpermeability is preactivated by ischemia. Based on the preceding considerations, we hypothesized that 1) hyperpermeability triggers a signaling mechanism that deactivates hyperpermeability and leads to the dynamic restoration of endothelial barrier function and 2) elevation of cAMP during reperfusion can deactivate hyperpermeability.

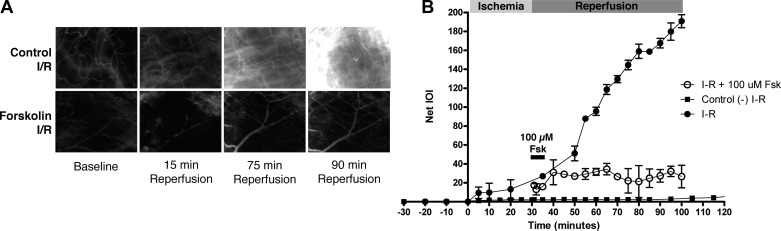

We first assessed whether stimulating an increase in cAMP would reduce the magnitude of hyperpermeability in vivo in the microcirculation of the hamster cremaster muscle. We used the hamster cremaster muscle as a model because the hamster microvasculature mimics the human vascular responses to proinflammatory agonists (10, 13, 17–19, 22, 29, 30). We used intravital microscopy to assess the response of the cremaster muscle microcirculation to elevated cAMP levels during I/R. After equilibration of the muscle preparation, we instituted ischemia for 30 min and observed reperfusion for 1 h (Fig. 4). Hyperpermeability occurred immediately upon reperfusion, confirming earlier reports (22, 23, 50–52). Figure 4 shows representative pictures of the hamster cremaster muscle microcirculation before I/R, during reperfusion, and during reperfusion in the presence of 100 μM forskolin. As shown in Fig. 4, there was a significant increase in permeability to FITC-dextran 70 in the reperfusion phase in control I/R preparations, as shown by the rise in net IOI from a baseline value of 9.8 ± 3.4 units to a peak value of 186.0 ± 7.3 units. To mimic clinical situations, we tested the role of cAMP signaling by acutely applying topical 100 μM forskolin at the time of reperfusion. This forskolin treatment greatly reduced the average IOI peak relative to I/R (25.6 ± 9.1 vs. 186.0 ± 7.3 in I/R, P < 0.05). Even though we applied forskolin only for the first 5 min of reperfusion, the deactivation of hyperpermeability was sustained for the duration of reperfusion. These results strongly suggest a role for cAMP in deactivating I/R-induced hyperpermeability.

Fig. 4.

Forskolin (Fsk) reduces ischemia-reperfusion (I/R)-induced microvascular hyperpermeability to FITC-dextran 70 in the hamster cremaster muscle. Integrated optical intensity (IOI; an index of permeability coefficient) of the interstitial space was quantified in 5 independent experiments per intervention by digital image analysis. A: representative images of the hamster cremaster microcirculation under baseline (control) and during reperfusion for muscles that underwent I/R (control I/R) and for muscles that underwent I/R and forskolin treatment at reperfusion (forskolin I/R; 5-min topical application of 100 μM forskolin at reperfusion). B: net IOI remained constant in control naïve cremaster muscles (no I/R; ■). Reperfusion caused a strong increase in IOI, indicating sustained hyperpermeability (●). Topical acute application of 100 μM forskolin for 5 min immediately upon release of the vascular clamp inhibited reperfusion-induced hyperpermeability (○). Net IOI baseline measurements before the onset of ischemia are displayed in the –30- to 0-min period. Topical application of forskolin is indicated by the solid bar starting at time = 30 min. Data are as means ± SE; n = 5 per intervention; one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

Forskolin-induced elevated cAMP concentration deactivates H/R-induced endothelial hyperpermeability in HMVECs.

To study the endothelial mechanisms underlying I/R-induced hyperpermeability, we subjected HMVECs to H/R and evaluated their responses to changes in Po2. To explore the potential benefits of forskolin-stimulated cAMP production on H/R-induced hyperpermeability in cultured ECs, we exposed HMVEC monolayers to H/R and measured permeability to FITC-dextran 70. While hypoxia failed to augment permeability, reoxygenation triggered significant hyperpermeability to FITC-dextran 70 (Fig. 5, A and B), recapitulating our in vivo observations in I/R. In parallel, we subjected HMVECs to the same H/R paradigm and applied 10 μM forskolin at the time of reoxygenation. Forskolin inhibited the reoxygenation-induced increase in permeability (Fig. 5A), confirming that enhanced endothelial cAMP signals deactivate barrier disruption in vitro. As an additional test, we explored whether GLP-1 would also inhibit the posthypoxia reoxygenation-induced hyperpermeability. As shown in Fig. 5B, 300 nM GLP-1 effectively reduced the hyperpermeability promoted by reoxygenation in hypoxic HMVECs. The beneficial action of both forskolin and GLP-1 can be reasonably attributed to their elevation of cAMP concentration in ECs (Fig. 3, C and D).

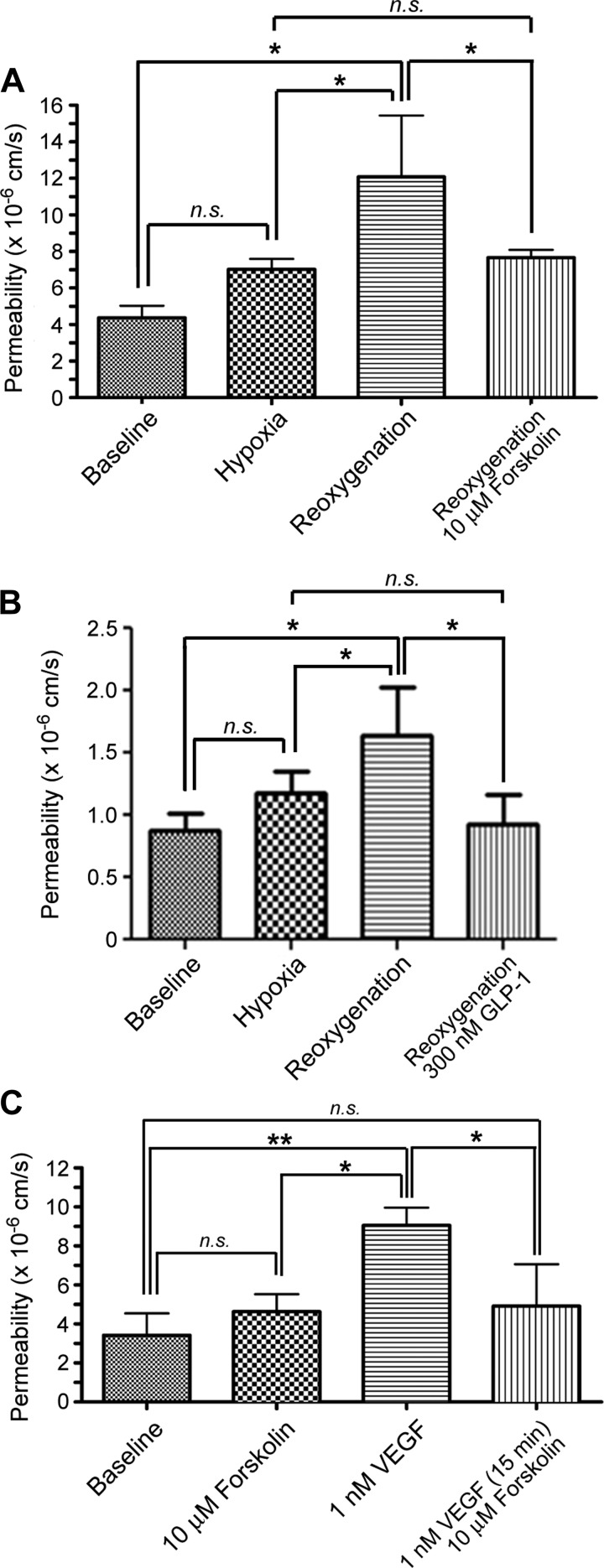

Fig. 5.

Forskolin deactivates H/R-induced hyperpermeability to FITC-dextran 70. A: hypoxia (30 min) did not significantly increase the permeability of HMVEC monolayers to FITC-dextran 70. In contrast, reoxygenation strongly increased endothelial permeability compared with baseline and with hypoxia alone (*P < 0.05). Stimulation of cAMP production with 10 μM forskolin applied at the onset of reoxygenation deactivated hyperpermeability. B: experiments similar to A except that GLP-1 was applied instead of forskolin. GLP-1 (300 nM), applied at reoxygenation, deactivated H/R-induced hyperpermeability. C: forskolin deactivated VEGF-induced hyperpermeability. Forskolin, applied at 10 µM, did not alter baseline permeability. One nanomole of VEGF significantly increased permeability. Ten micromoles of forskolin administered 15 min after the application of 1 nM VEGF deactivated VEGF-induced hyperpermeability. A–C: n = 5. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

To further examine the capacity of forskolin stimulated increases in cAMP concentration to reverse hyperpermeability, we evaluated in vitro whether increasing cAMP concentration deactivates VEGF-induced hyperpermeability. We stimulated HMVEC monolayers with 1 nM VEGF or with 1 nM VEGF followed by 10 μM forskolin after 15 min of VEGF application and calculated the permeability coefficient for FITC-dextran 70. VEGF significantly increased FITC-dextran 70 permeability in HMVEC monolayers compared with baseline levels (Fig. 5C). Forskolin did not change baseline permeability; however, forskolin applied 15 min after VEGF stimulation very efficiently and effectively deactivated the increase in permeability to FITC-dextran 70 (Fig. 5C).

The cAMP-Epac1-Rap1 pathway mediates forskolin-induced deactivation of endothelial hyperpermeability.

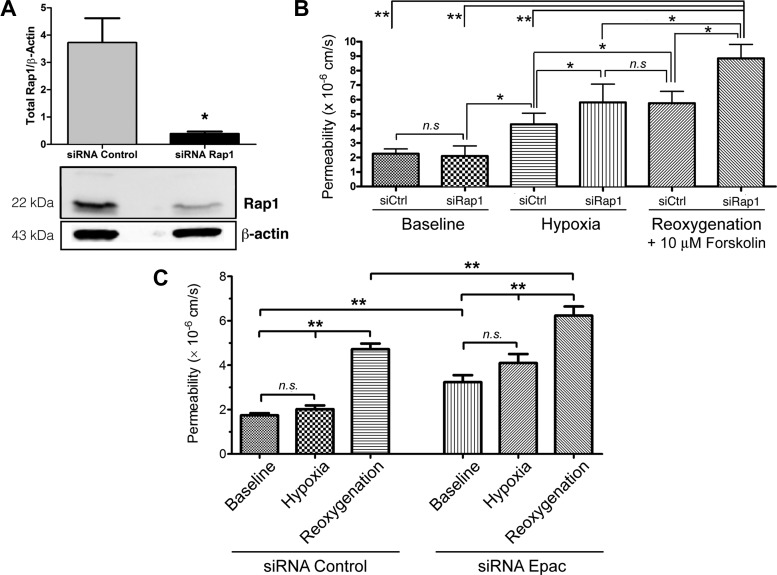

cAMP exerts its barrier-enhancing actions by activating multiple signaling pathways in ECs. Here, we evaluated the importance of the Epac1/Rap1 pathway in the cAMP-driven deactivation of endothelial hyperpermeability. To do so, we performed permeability measurements on HMVEC monolayers depleted of Rap1 by siRNA. We confirmed Rap1 depletion 72 h posttransfection by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6A). We exposed control and Rap1-depleted HMVEC monolayers to 30 min of hypoxia followed by 60 min of reoxygenation (Fig. 6B). Depletion of Rap1 did not alter baseline permeability in nonstimulated cells. Hypoxia caused a significant elevation in permeability in ECs transfected with nontargeting control siRNA and in ECs transfected with siRNA Rap1 relative to nonstimulated nontargeting siRNA and siRNA Rap1-transfected cells. This finding was unexpected as in previous experiments (in vivo and in vitro) hypoxia did not directly cause changes in permeability. The hypoxia-induced increase in permeability may simply reflect that siRNA transfection of ECs is not an innocuous intervention. We speculate that it is also possible that the nontargeting siRNA may accidentally undermine target elements that regulate cell adhesion. Hypoxia-induced increase in permeability in the ECs transfected with siRNA against Rap1 would be expected or could be anticipated because Rap1 is an important positive regulator of cell adhesion, and its depletion would render ECs vulnerable to challenges such as hypoxia. Consistent with this interpretation, hypoxia-induced hyperpermeability in siRNA Rap1 ECs was significantly greater than hypoxia-induced increase in permeability in siRNA nontargeting ECs. Reoxygenation increased permeability to FITC-dextran 70 in ECs transfected with nontargeting siRNA ECs relative to their hypoxia levels, but because 10 µM forskolin was administered at reoxygenation, the increase in permeability reached only values comparable with the level of hypoxia-induced hyperpermeability in siRNA Rap1 ECs. Importantly, the central observation in this series of experiments is that reoxygenation significantly stimulated hyperpermeability, relative to hypoxia and baseline controls, despite the application of 10 µM forskolin in Rap1-depleted ECs (Fig. 6B). Our combined findings, that Rap1 activity increases during reoxygenation (Fig. 3B) and that 10 µM forskolin failed to reduce reoxygenation-induced hyperpermeability in cells transfected with siRNA Rap1 (Fig. 6B), demonstrate that Rap1 activity is required for forskolin-stimulated deactivation of H/R-induced endothelial hyperpermeability.

Fig. 6.

cAMP operates via exchange protein activated by cAMP 1 (Epac1) and Rap1 to restore baseline permeability. A: significant depletion of Rap1 was obtained with specific Rap1 small interfering (si)RNA in HMVECs. β-Actin served as a loading control. B: Rap1 is required for forskolin-stimulated deactivation of H/R-induced endothelial hyperpermeability. HMVECs transfected with either nontargeting siRNA [control (siCtrl)] or Rap1-specific siRNA were subjected to normoxia (baseline) or 30 min of hypoxia (Po2 < 20 mmHg) followed by 60 min of normoxic reoxygenation (Po2 = 159 mmHg). Depletion of Rap1 did not change permeability compared with normoxic baseline. Hypoxia elevated basal permeability of control siRNA and Rap1 siRNA. Reoxygenation significantly increased hyperpermeability in HMVEC monolayers depleted of Rap1, despite the administration of forskolin (10 μM) upon the onset of reoxygenation. C: Epac1 and permeability in H/R. Hypoxia did not increase permeability in HMVECs transfected with nontargeting siRNA but caused hyperpermeability in Epac-depleted HMVECs. Reoxygenation caused significant hyperpermeability in nontargeting siRNA-transfected HMVECs. Depletion of Epac1 with Epac1 siRNA elevated baseline permeability and greatly enhanced H/R-induced hyperpermeability. A–C: data are means ± SE; n = 5. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. A: two-tailed Student’s t-test comparison. B and C: one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

To further support the preceding studies, we investigated the relevance of Epac1 in H/R. The rationale for these experiments was that Epac1 is directly stimulated by cAMP and, in turn, Epac1 activates Rap1. As in the preceding experiments, we exposed control and Epac1-depleted HMVEC monolayers to 30 min of hypoxia followed by 60 min of reoxygenation and measured the endothelial monolayer permeability to FITC-dextran 70 (Fig. 6C). Our results demonstrate that depletion of Epac1 elevates baseline permeability (loss of barrier integrity) relative to control baseline. These results also illustrate that transfection of ECs with siRNA against regulators of cell adhesion renders them vulnerable to hypoxia. Despite the elevation in baseline permeability, depletion of Epac1 led to a significant increase in reoxygenation-induced hyperpermeability compared with all other groups including cells transfected with nontargeting siRNA exposed to H/R (Fig. 6C).

DISCUSSION

Here, we demonstrate that 1) mechanisms involving upregulation of VEGF protein synthesis contribute to microvascular hyperpermeability in I/R after 4 h of ischemia but not for shorter times; this suggests that VEGF may be a significant player in vascular damage resulting from prolonged ischemia and that other proinflammatory factors regulate permeability in brief ischemia; 2) reoxygenation of hypoxic ECs causes a significant increase in cAMP concentration and in activation of Rap1; 3) stimulation of cAMP signaling pathways at the time of reperfusion deactivates I/R-induced and H/R-induced hyperpermeability in vivo and in vitro, respectively; and 4) Rap1 is required for forskolin-stimulated cAMP-induced restoration of endothelial barrier function after H/R. These findings suggest that targeted management of endothelial cAMP may serve as an adjunct therapeutic modality to prevent or minimize the development of compartment syndrome after revascularization and reinstitution of blood flow in I/R.

I/R alters VEGF expression and synthesis in a time-dependent manner.

Prolonged disruption of blood supply to skeletal muscle promotes the production and release of factors that increase vascular permeability. To date, the most potent permeability-inducing factor known is VEGF (16, 25, 48) and, specifically, VEGF164/165 (3, 41, 56). Once synthesized, VEGF induces permeability within a short time as VEGF-induced phosphorylation of the VEGF2 receptor leads to stimulation and activation of Vav2, Rac1, and PAK1 and internalization of VE-cadherin into clathrin-coated vesicles (4, 28). Consequently, our initial hypothesis to explore the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying I/R-induced hyperpermeability was that VEGF is an important agent that induces postischemic changes in microvascular permeability. Our observation that increased VEGF mRNA expression was not detected until 4 h after the onset of ischemia is significant since increases in hyperpermeability occur at much shorter ischemic periods in the cremaster muscle (9, 32, 50, 51), specifically after 30 min of ischemia when VEGF expression is at baseline levels (Fig. 2). This time difference between VEGF mRNA expression and the permeability response to H/R advances the concept that different time-dependent mechanisms exist in I/R that account for I/R-induced hyperpermeability observed immediately upon reperfusion versus prolonged hyperpermeability. In this context, we have shown that TNF-α and PAF mimic I/R (39, 52) and may represent leading candidates for being among the factors responsible for the hyperpermeability observed in reperfusion after short-duration ischemia, perhaps through S-nitrosylation of junctional proteins (31, 35).

Reoxygenation increases EC cAMP and activated Rap1.

Inflammatory molecules induce conformational changes at cell junctions and weaken the endothelial barrier by decreasing intracellular cAMP levels (45, 47). We tested whether ECs exposed to H/R deactivate hyperpermeability by increasing intracellular cAMP. We observed significant increases in cAMP concentration during reoxygenation (Fig. 3A). The data suggest that changes in cAMP during the reoxygenation period represent a dynamic mechanism to deactivate hyperpermeability. In addition, we observed that activated Rap1 increases during reoxygenation, probably as a consequence of stimulation by increased cAMP concentration.

Deactivation of I/R-induced hyperpermeability.

Vascular hyperpermeability is a hallmark of the endothelial inflammatory response to revascularization after ischemia. It is essential for the initiation of tissue repair, but if not resolved in a timely manner, it induces additional pathology (e.g., compartment syndrome in postischemic skeletal muscle) and delays homeostatic recovery. Much is known about the mechanisms involved in the onset of hyperpermeability; accordingly, therapeutic efforts have focused on identifying methods that interfere with onset mechanisms. However, since many negative effects of hyperpermeability are due to its persistence beyond what is required for preserving organ function, we endorse a targeted therapeutic approach focusing on mechanisms that terminate hyperpermeability and thereby restore microvascular barrier properties.

Despite many efforts to manage the hyperpermeability-induced edema associated with inflammation, there is currently no definitive clinical treatment for endothelial hyperpermeability or repair of endothelial damage (20). In our experiments, cAMP agonists restore barrier function after I/R injury and support the concept that cAMP reduces disruption of EC junctions (57). Forskolin, administered at the time of reperfusion (reoxygenation), efficiently deactivated the I/R- and H/R-induced large increases in permeability in the hamster cremaster and across ECs (Figs. 4 and 5). In concurrence with the changes in cAMP concentration (Fig. 3A) and in activated Rap1 (Fig. 3B), our in vivo and vitro data support the concept that restoration of barrier properties is a process of active deactivation of the hyperpermeability developed during I/R. While the complexity of downstream signaling pathways continues to be elucidated, our data show that a forskolin-induced elevation in cAMP is sufficient to deactivate I/R-induced hyperpermeability in vivo and to restore the EC barrier properties toward baseline in vitro.

cAMP inactivates hyperpermeability through Epac1/Rap1 activation.

Rap1 is a small GTPase that contributes to the normal function of ECs. Endothelial junctional proteins are regulated in part by Rap1 in response to cAMP activation through Epac1. Our experiments depleting Epac1 and Rap1 via siRNA in HMVECs demonstrate that Epac1 and Rap1 play a significant and fundamental role in restoring the barrier properties of the endothelium in the inflammatory phase of H/R. Depletion of Rap1 in ECs abolished the barrier-stabilizing effects of cAMP after H/R and prevented the deactivation of hyperpermeability caused by forskolin-enhanced cAMP production (Fig. 6B).

We did not explore simultaneously the influence of H/R on siRap1-transfected cells in the absence of forskolin. The only reason to do so would be to test whether forskolin could have somehow reduced H/R-stimulated hyperpermeability in siRap1 HMVECs in Fig. 6B. However, comparison of the ratio of H/R-stimulated hyperpermeability to baseline permeability in Figs. 5A and 6C (which yield ratios of ~3 to 1) to the same ratio in Fig. 6B (~4 to 1) fails to support the idea that forskolin reduces reoxygenation-induced hyperpermeability in HMVECs transfected with siRap1 or indeed has any effect when Rap1 is knocked down. Currently, the literature shows that cell adhesion and barrier integrity are regulated by cAMP through activation of the Epac1-Rap1 axis (15, 26, 38). Thus, while it is plausible that other mechanisms are also involved, our results demonstrate that stimulation of cAMP production in ECs deactivates hyperpermeability via Epac1/Rap1 in H/R in HMVECs and (by extrapolation) in postischemic striated muscle.

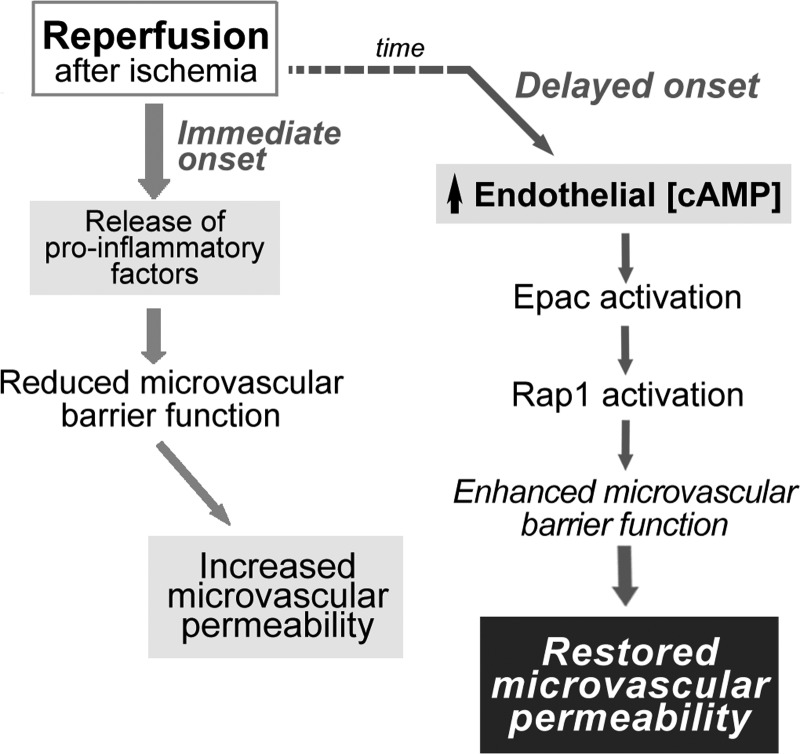

In summary, our data demonstrate that different mechanisms operate to increase microvascular permeability in response to ischemia, depending on the duration of the ischemic period. In addition, as shown in Fig. 7, we propose that I/R promotes at least two processes concerning microvascular transport of macromolecules 1) hyperpermeability, which is physiologically important to rebuild and repair damaged tissue, and 2) an active process that leads to the deactivation of hyperpermeability and restoration of barrier integrity to reestablish homeostasis. Postischemic hyperpermeability to macromolecules is triggered immediately by the release of proinflammatory agents (possibly PAF, TNF-α, and/or other mediators). Deactivation of hyperpermeability has a delayed onset, probably to facilitate blood-tissue exchange of macromolecules needed for tissue repair. The deactivation process involves an increase in cAMP concentration with activation of Epac1 and Rap1 to stimulate cell adhesion and restore barrier integrity of the endothelial vascular layer (Fig. 7). Investigation of the interesting hypothesis that there is a cellular integrating center that regulates the onset of hyperpermeability in response to inflammatory agonists and determines the timing of its deactivation is beyond the scope of the present work. Because compartment syndrome is a major obstacle for restoration of function in postischemic muscle, we suggest, as translational potential, that interventions that increase cAMP, by stimulation of endothelial adenylyl cyclase, may serve as adjuvant therapy during the revascularization of postischemic organs to prevent the development of compartment syndrome.

Fig. 7.

Schematic illustration of fundamental processes in reperfusion of postischemic striated muscle and reoxygenation of endothelial cells. Release of proinflammatory factors [platelet-activating factor (PAF), TNF-α, etc. for short ischemia or VEGF164/165 for long ischemia] occurs immediately upon reestablishment of blood flow (reperfusion) or reoxygenation. The functional initial hyperpermeability promotes and facilitates repair of tissue damage. The onset of deactivation of hyperpermeability is a delayed process. The potential regulatory role of cAMP via Epac1 and Rap1 is highlighted.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants 5-R01-HL-070634 and 5-R01-HL-088479 and Chile's Fondecyt 1130769.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.H.K., F.A.S., and W.N.D. conceived and designed research; A.H.K., P.E.M., H.A., and R.G.D. performed experiments; A.H.K., P.R.N., D.D.K., F.A.S., and W.N.D. analyzed data; A.H.K., H.A., R.G.D., D.D.K., A.L.H., F.A.S., and W.N.D. interpreted results of experiments; A.H.K., P.E.M., R.G.D., P.R.N., and W.N.D. prepared figures; A.H.K. and W.N.D. drafted manuscript; A.H.K., P.E.M., H.A., R.G.D., P.R.N., D.D.K., A.L.H., F.A.S., and W.N.D. approved final version of manuscript; P.E.M., A.L.H., and W.N.D. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of A. H. Korayem: Dept. of Surgery, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029.

Present address of H. Aramoto: Div, of Vascular Surgery, Dept. of Surgery, Sakakibara Heart Institute, Tokyo 183-0003, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson RH, Ly JC, Sarai RK, Lenz JF, Altangerel A, Drenckhahn D, Curry FE. Epac/Rap1 pathway regulates microvascular hyperpermeability induced by PAF in rat mesentery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1188–H1196, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00937.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aramoto H, Breslin JW, Pappas PJ, Hobson RW 2nd, Durán WN. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates differential signaling pathways in in vivo microcirculation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1590–H1598, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00767.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker PM, Waltenberger J, Yachechko R, Mirzapoiazova T, Sham JS, Lee CG, Elias JA, Verin AD. Neuropilin-1 regulates vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated endothelial permeability. Circ Res 96: 1257–1265, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000171756.13554.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckers CM, van Hinsbergh VW, van Nieuw Amerongen GP. Driving Rho GTPase activity in endothelial cells regulates barrier integrity. Thromb Haemost 103: 40–55, 2010. doi: 10.1160/TH09-06-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bekker AY, Ritter AB, Durán WN. Analysis of microvascular permeability to macromolecules by video-image digital processing. Microvasc Res 38: 200–216, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birukova AA, Fu P, Xing J, Birukov KG. Rap1 mediates protective effects of iloprost against ventilator-induced lung injury. J Appl Physiol (1985) 107: 1900–1910, 2009. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00462.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birukova AA, Wu T, Tian Y, Meliton A, Sarich N, Tian X, Leff A, Birukov KG. Iloprost improves endothelial barrier function in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. Eur Respir J 41: 165–176, 2013. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00148311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaisdell FW. The pathophysiology of skeletal muscle ischemia and the reperfusion syndrome: a review. Cardiovasc Surg 10: 620–630, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0967-2109(02)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blebea J, Cambria RA, DeFouw D, Feinberg RN, Hobson RW 2nd, Durán WN. Iloprost attenuates the increased permeability in skeletal muscle after ischemia and reperfusion. J Vasc Surg 12: 656–665, 1990. 10.1067/mva.1990.25129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borić MP, Roblero JS, Durán WN. Quantitation of bradykinin-induced microvascular leakage of FITC-dextran in rat cremaster muscle. Microvasc Res 33: 397–412, 1987. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(87)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bos JL. Epac proteins: multi-purpose cAMP targets. Trends Biochem Sci 31: 680–686, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bos JL. Linking Rap to cell adhesion. Curr Opin Cell Biol 17: 123–128, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslin JW, Pappas PJ, Cerveira JJ, Hobson RW 2nd, Durán WN. VEGF increases endothelial permeability by separate signaling pathways involving ERK-1/2 and nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H92–H100, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00330.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundey RA, Insel PA. Adenylyl cyclase 6 overexpression decreases the permeability of endothelial monolayers via preferential enhancement of prostacyclin receptor function. Mol Pharmacol 70: 1700–1707, 2006. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cullere X, Shaw SK, Andersson L, Hirahashi J, Luscinskas FW, Mayadas TN. Regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function by Epac, a cAMP-activated exchange factor for Rap GTPase. Blood 105: 1950–1955, 2005. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Detmar M, Brown LF, Berse B, Jackman RW, Elicker BM, Dvorak HF, Claffey KP. Hypoxia regulates the expression of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (VPF/VEGF) and its receptors in human skin. J Invest Dermatol 108: 263–268, 1997. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12286453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dillon PK, Durán WN. Effect of platelet-activating factor on microvascular permselectivity: dose-response relations and pathways of action in the hamster cheek pouch microcirculation. Circ Res 62: 732–740, 1988. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.62.4.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dillon PK, Fitzpatrick MF, Ritter AB, Durán WN. Effect of platelet-activating factor on leukocyte adhesion to microvascular endothelium. Time course and dose-response relationships. Inflammation 12: 563–573, 1988. doi: 10.1007/BF00914318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dillon PK, Ritter AB, Durán WN. Vasoconstrictor effects of platelet-activating factor in the hamster cheek pouch microcirculation: dose-related relations and pathways of action. Circ Res 62: 722–731, 1988. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.62.4.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dozier KC, Cureton EL, Kwan RO, Curran B, Sadjadi J, Victorino GP. Glucagon-like peptide-1 protects mesenteric endothelium from injury during inflammation. Peptides 30: 1735–1741, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durán WN, Breslin JW, Sánchez FA. The NO cascade, eNOS location, and microvascular permeability. Cardiovasc Res 87: 254–261, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durán WN, Dillon PK. Acute microcirculatory effects of platelet-activating factor. J Lipid Mediat 2, Suppl: S215–S227, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durán WN, Dillon PK. Effects of ischemia-reperfusion injury on microvascular permeability in skeletal muscle. Microcirc Endothelium Lymphatics 5: 223–239, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion–from mechanism to translation. Nat Med 17: 1391–1401, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fava RA, Olsen NJ, Spencer-Green G, Yeo KT, Yeo TK, Berse B, Jackman RW, Senger DR, Dvorak HF, Brown LF. Vascular permeability factor/endothelial growth factor (VPF/VEGF): accumulation and expression in human synovial fluids and rheumatoid synovial tissue. J Exp Med 180: 341–346, 1994. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukuhara S, Sakurai A, Sano H, Yamagishi A, Somekawa S, Takakura N, Saito Y, Kangawa K, Mochizuki N. Cyclic AMP potentiates vascular endothelial cadherin-mediated cell-cell contact to enhance endothelial barrier function through an Epac-Rap1 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol 25: 136–146, 2005. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.136-146.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrett TA, Van Buul JD, Burridge K. VEGF-induced Rac1 activation in endothelial cells is regulated by the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav2. Exp Cell Res 313: 3285–3297, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gawlowski DM, Durán WN. Dose-related effects of adenosine and bradykinin on microvascular permselectivity to macromolecules in the hamster cheek pouch. Circ Res 58: 348–355, 1986. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.58.3.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gawlowski DM, Ritter AB, Durán WN. Reproducibility of microvascular permeability responses to successive topical applications of bradykinin in the hamster cheek pouch. Microvasc Res 24: 354–363, 1982. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(82)90022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guequén A, Carrasco R, Zamorano P, Rebolledo L, Burboa P, Sarmiento J, Boric MP, Korayem A, Durán WN, Sánchez FA. S-nitrosylation regulates VE-cadherin phosphorylation and internalization in microvascular permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H1039–H1044, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatakeyama T, Pappas PJ, Hobson RW 2nd, Boric MP, Sessa WC, Durán WN. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulates microvascular hyperpermeability in vivo. J Physiol 574: 275–281, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim D, Armenante PM, Durán WN. Mathematical modeling of mass transfer in microvascular wall and interstitial space. Microvasc Res 40: 358–378, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(90)90033-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lal BK, Varma S, Pappas PJ, Hobson RW 2nd, Durán WN. VEGF increases permeability of the endothelial cell monolayer by activation of PKB/akt, endothelial nitric-oxide synthase, and MAP kinase pathways. Microvasc Res 62: 252–262, 2001. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marín N, Zamorano P, Carrasco R, Mujica P, González FG, Quezada C, Meininger CJ, Boric MP, Durán WN, Sánchez FA. S-nitrosation of β-catenin and p120 catenin: a novel regulatory mechanism in endothelial hyperpermeability. Circ Res 111: 553–563, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.274548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nase GP, Tuttle J, Bohlen HG. Reduced perivascular Po2 increases nitric oxide release from endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H507–H515, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00759.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ng YS, Rohan R, Sunday ME, Demello DE, D’Amore PA. Differential expression of VEGF isoforms in mouse during development and in the adult. Dev Dyn 220: 112–121, 2001. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noda K, Zhang J, Fukuhara S, Kunimoto S, Yoshimura M, Mochizuki N. Vascular endothelial-cadherin stabilizes at cell-cell junctions by anchoring to circumferential actin bundles through alpha- and beta-catenins in cyclic AMP-Epac-Rap1 signal-activated endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 21: 584–596, 2010. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noel AA, Hobson RW 2nd, Durán WN. Platelet-activating factor and nitric oxide mediate microvascular permeability in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Microvasc Res 52: 210–220, 1996. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogawa S, Koga S, Kuwabara K, Brett J, Morrow B, Morris SA, Bilezikian JP, Silverstein SC, Stern D. Hypoxia-induced increased permeability of endothelial monolayers occurs through lowering of cellular cAMP levels. Am J Physiol 262: C546–C554, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roth L, Prahst C, Ruckdeschel T, Savant S, Weström S, Fantin A, Riedel M, Héroult M, Ruhrberg C, Augustin HG. Neuropilin-1 mediates vascular permeability independently of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 activation. Sci Signal 9: ra42, 2016. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aad3812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sánchez FA, Rana R, González FG, Iwahashi T, Durán RG, Fulton DJ, Beuve AV, Kim DD, Durán WN. Functional significance of cytosolic endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS): regulation of hyperpermeability. J Biol Chem 286: 30409–30414, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.234294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sánchez FA, Rana R, Kim DD, Iwahashi T, Zheng R, Lal BK, Gordon DM, Meininger CJ, Durán WN. Internalization of eNOS and NO delivery to subcellular targets determine agonist-induced hyperpermeability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 6849–6853, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812694106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sayner SL. Emerging themes of cAMP regulation of the pulmonary endothelial barrier. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300: L667–L678, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00433.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schick MA, Wunder C, Wollborn J, Roewer N, Waschke J, Germer CT, Schlegel N. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition as a therapeutic approach to treat capillary leakage in systemic inflammation. J Physiol 590: 2693–2708, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.232116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlegel N, Waschke J. cAMP with other signaling cues converges on Rac1 to stabilize the endothelial barrier- a signaling pathway compromised in inflammation. Cell Tissue Res 355: 587–596, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1755-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlegel N, Waschke J. Impaired cAMP and Rac 1 signaling contribute to TNF-alpha-induced endothelial barrier breakdown in microvascular endothelium. Microcirculation 16: 521–533, 2009. doi: 10.1080/10739680902967427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science 219: 983–985, 1983. doi: 10.1126/science.6823562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen Q, Rigor RR, Pivetti CD, Wu MH, Yuan SY. Myosin light chain kinase in microvascular endothelial barrier function. Cardiovasc Res 87: 272–280, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suval WD, Durán WN, Borić MP, Hobson RW 3rd, Berendsen PB, Ritter AB. Microvascular transport and endothelial cell alterations preceding skeletal muscle damage in ischemia and reperfusion injury. Am J Surg 154: 211–218, 1987. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suval WD, Hobson RW 2nd, Borić MP, Ritter AB, Durán WN. Assessment of ischemia reperfusion injury in skeletal muscle by macromolecular clearance. J Surg Res 42: 550–559, 1987. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(87)90031-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takenaka H, Oshiro H, Kim DD, Thompson PN, Seyama A, Hobson RW 2nd, Durán WN. Microvascular transport is associated with TNF plasma levels and protein synthesis in postischemic muscle. Am J Physiol 274: H1914–H1919, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toth A, Pal M, Tischler ME, Johnson PC. Are there oxygen-deficient regions in resting skeletal muscle? Am J Physiol 270: H1933–H1939, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Usui T, Ishida S, Yamashiro K, Kaji Y, Poulaki V, Moore J, Moore T, Amano S, Horikawa Y, Dartt D, Golding M, Shima DT, Adamis AP. VEGF164(165) as the pathological isoform: differential leukocyte and endothelial responses through VEGFR1 and VEGFR2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45: 368–374, 2004. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varma S, Breslin JW, Lal BK, Pappas PJ, Hobson RW 2nd, Durán WN. p42/44MAPK regulates baseline permeability and cGMP-induced hyperpermeability in endothelial cells. Microvasc Res 63: 172–178, 2002. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang L, Zeng H, Wang P, Soker S, Mukhopadhyay D. Neuropilin-1-mediated vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent endothelial cell migration. J Biol Chem 278: 48848–48860, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waschke J, Drenckhahn D, Adamson RH, Barth H, Curry FE. cAMP protects endothelial barrier functions by preventing Rac-1 inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2427–H2433, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00556.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whalen WJ, Buerk D, Thuning C, Kanoy BE Jr, Durán WN. Tissue PO2, VO2, venous PO2 and perfusion pressure in resting dog gracilis muscle perfused at constant flow. Adv Exp Med Biol 75: 639–655, 1976. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3273-2_75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]