Using measurements of contractility, protein abundance, kinase activity, and confocal colocalization in fetal and adult ovine cerebral arteries, the present study demonstrates that long-term hypoxia diminishes the ability of cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) to cause vasorelaxation through suppression of its colocalization and interaction with large-conductance Ca2+-sensitive K+ (BK) channel proteins in cerebrovascular smooth muscle. These experiments are among the first to demonstrate hypoxic changes in BK subunit abundances in fetal cerebral arteries and also introduce the use of advanced methods of confocal colocalization to study interaction between PKG and its targets.

Keywords: cGMP, chronic hypoxia, guanylate cyclase, iberiotoxin, confocal, colocalization

Abstract

Long-term hypoxia (LTH) attenuates nitric oxide-induced vasorelaxation in ovine middle cerebral arteries. Because cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) is an important mediator of NO signaling in vascular smooth muscle, we tested the hypothesis that LTH diminishes the ability of PKG to interact with target proteins and cause vasorelaxation. Prominent among proteins that regulate vascular tone is the large-conductance Ca2+-sensitive K+ (BK) channel, which is a substrate for PKG and is responsive to phosphorylation on multiple serine/threonine residues. Given the influence of these proteins, we also examined whether LTH attenuates PKG and BK channel protein abundances and PKG activity. Middle cerebral arteries were harvested from normoxic and hypoxic (altitude of 3,820 m for 110 days) fetal and adult sheep. These arteries were denuded and equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2 in the presence of N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) to inhibit potential confounding influences of events upstream from PKG. Expression and activity of PKG-I were not significantly affected by chronic hypoxia in either fetal or adult arteries. Pretreatment with the BK inhibitor iberiotoxin attenuated vasorelaxation induced by 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)guanosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate in normoxic but not LTH arteries. The spatial proximities of PKG with BK channel α- and β1-proteins were examined using confocal microscopy, which revealed a strong dissociation of PKG with these proteins after LTH. These results support our hypothesis that hypoxia reduces the ability of PKG to attenuate vasoconstriction in part through suppression of the ability of PKG to associate with and thereby activate BK channels in arterial smooth muscle.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Using measurements of contractility, protein abundance, kinase activity, and confocal colocalization in fetal and adult ovine cerebral arteries, the present study demonstrates that long-term hypoxia diminishes the ability of cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) to cause vasorelaxation through suppression of its colocalization and interaction with large-conductance Ca2+-sensitive K+ (BK) channel proteins in cerebrovascular smooth muscle. These experiments are among the first to demonstrate hypoxic changes in BK subunit abundances in fetal cerebral arteries and also introduce the use of advanced methods of confocal colocalization to study interaction between PKG and its targets.

long-term hypoxia (LTH) triggers adaptive responses in the developing fetus that can enhance long-term risk for many pathologies (40). In particular, maternal and perinatal hypoxia induce changes in vascular structure and reactivity that manifest as reduced vascular compliance and capacity for vasorelaxation (37). Correspondingly, nitric oxide (NO) and the NO pathway, which potently influence vascular tone and vasorelaxation, appear quite vulnerable to modulation by LTH (21). Hypoxia can compromise multiple components of this pathway including vascular endothelial function and endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) activity, vascular soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) abundance and activity, and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) activity (38). Because PKG is a prominent end-point effector of the NO pathway, this investigation focused on the influence of LTH on the ability of activated PKG to modify its target proteins and regulate vascular tone.

Vascular tone is largely a product of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. Accordingly, acute regulation of tone by PKG involves both terms of this equation (33). PKG influences [Ca2+]i in the following ways: by inhibiting release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), by stimulating extrusion via plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase transport protein (PMCA) and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (15), and by stimulating sequestration via the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) into the SR (9). Also, PKG-mediated phosphorylation of the large-conductance Ca2+-sensitive K2+ (BK) channel α protein increases its Ca2+ sensitivity (25, 52) and thereby indirectly inhibits Ca2+ entry by promoting hyperpolarization and attenuating voltage-gated Ca2+ channel activity. PKG can further influence calcium entry by modulating spark activity secondary to action on ryanodine receptors (RyRs) (18, 22, 24). PKG also acutely influences myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity at numerous regulatory points, including activation of myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP) (34), phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) (28), phosphorylation of 20-kDa heat shock protein (HSP20) (6), and more. The BK channel is of particular interest as it is a dominant mediator of acute PKG-induced vasorelaxation (4) and is also vulnerable to the stress of LTH (44). Long-term influences of PKG involve its ability to promote and maintain the contractile vascular smooth muscle (VSM) phenotype, which is likewise vulnerable to LTH. PKG or PKA action at Ser133 on cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) promotes expression of VSM contractile proteins (7, 39). PKG also directly and indirectly regulates phenotype by influencing contractile gene expression via serum response factor (SRF) and myocardin (46). Published evidence has demonstrated that high PKG activity correlates with increased myocardin expression and that myocardin promotes SRF binding to CArG promoter sequences (51). Also, PKG phosphorylation of Ser104 on cysteine-rich protein-4 (CRP4) promotes cooperativity of GATA6 and SRF, which likewise leads to increased SRF binding to CArG (49). In turn, SRF binding to CArG domains activates a repertoire of VSM cell genes that characterize the contractile phenotype (49). More empirically, it has been shown that activation of PKG correlates with expression of VSM contractile proteins (29) and that hypoxia-induced attenuation of PKG leads to repression of VSM cell-specific genes (50), whereas overexpression of PKG reverses this. This implies a critical role for PKG in establishing and maintaining the contractile VSM phenotype.

It is apparent that PKG plays a prominent role in acute and long-term establishment and maintenance of the contractile VSM phenotype via multiple pathways that are vulnerable to the influence of LTH. Altered structure-function relations under hypoxic stress represent an adaptive homeostasis that favors near-term survival. Yet, mechanisms underlying the disruptive effects of LTH on the role of PKG in cerebral VSM remain largely unexplored. The observed loss of contractile function may represent a lower density of contractile proteins and therefore lower contractant efficacy; it could represent a shift within a subpopulation of contractile VSMs to a synthetic phenotype; or it could represent, not exclusively, a reorganization or inactivation of the existing contractile apparatus. The main hypothesis explored here is that hypoxia alters the ability of PKG to influence its target proteins, and the BK channel in particular, in part because of a structural reorganization of effector proteins. A corollary to this is that maturation from fetus to adult influences the response to hypoxic stress. To test these ideas, it was of interest to quantify the relative influence of the BK channel in cerebral VSM under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. To accomplish this, we used the selective BK channel inhibitor iberiotoxin to distinguish BK channel versus non-BK channel effects (8, 17, 41). Iberiotoxin is uniquely selective for the BK channel, in contrast with other commonly used channel blockers such as charybdotoxin and tetraethylammonium, which inhibit other K2+ channels (e.g., voltage-gated K2+ channel Kv1.3) nonselectively (41). It has been shown that iberiotoxin uniquely blocks the BK channel with high affinity by binding to and occluding the external aperture of the BK channel (17). In addition, our previous studies have demonstrated that iberiotoxin is highly efficacious against BK channels in ovine cerebral arteries (27, 42).

To study vasorelaxation, we used 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT; also known as serotonin) as a contractant, against which the effects of relaxation could be contrasted. Use of 5-HT required that we validate the effect of PKG and LTH independently on the 5-HT receptor (5-HTR) pathway; to this end, we examined the influence of PKG and hypoxia on 5-HTR affinity and receptor occupancy. In this study, we used middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) from fetal and adult sheep to examine two main end points: a functional end point, the 5-HT concentration response; and a structure-relational end point, which was the organization among vasorelaxant proteins (PKG, BKα, BKβ1, and RyRs) as measured with confocal microscopy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures in this study were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Loma Linda University and adhered strictly to the policies and practices set forth by the National Institutes of Health guide governing the care and use of laboratory animals.

Tissue harvest and preparation.

All MCAs used in this study were harvested from normoxic and chronically hypoxic term fetal (139–142 days gestation, where full term is 145 days) and young (18–24 mo old) nulliparous adult sheep. Normoxic animals were obtained (720-m altitude, Nebeker Ranch, Lancaster, CA) and brought to the Loma Linda University animal care facility (353-m altitude), where arterial Po2 () averaged 23 ± 1 and 102 ± 2 Torr in fetal and adult sheep, respectively (23). Chronically hypoxic sheep were maintained for ~110 days at high altitude (altitude of 3,820 m, Barcroft Laboratory, White Mountain Research Station, Bishop, CA). For pregnant ewes, the period at altitude corresponded to the final 110 days of gestation. At high altitude, values averaged 19 ± 1 and 64 ± 2 Torr for fetal and adult sheep, respectively. Sheep brought to our animal care facility from high altitude were maintained at low by placement of a tracheal catheter that was ventilated with an N2-enhanced mixture of breathing gas to maintain a of ~60 Torr. For hypoxic animals, arterial blood was obtained and monitored intermittently several times a day, and the breathing gas ratios were adjusted as necessary. Pregnant ewes were anesthetized with 30 mg/kg pentobarbital, intubated, and then placed on 1.5–2.0% isoflurane. The anesthetized fetus was then exteriorized through a midline vertical laparotomy and euthanized by rapid removal of the heart and exsanguination. Nonpregnant adult animals were euthanized by intravenous administration of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) and phenytoin sodium (10 mg/kg). Harvested MCAs were placed in sodium Krebs buffer solution containing (in mM) 122 NaCl, 25.6 NaHCO3, 5.17 KCl, 2.49 MgSO4, 1.60 CaCl2, 2.56 dextrose, 0.027 EGTA, and 0.114 ascorbic acid bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. Arteries were subsequently debrided of loose extravascular and connective tissue, and the endothelium was substantially disrupted (herein referred to as “denuded”) by passage of an abrasive tungsten wire through the lumen followed by irrigation with Krebs buffer. Because residual endothelial activity could potentially confound the results, 100 µM NG-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA) and 100 µM N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) were added to the Krebs buffer to inhibit endothelial NO release and minimize sGC activity. Functional experiments on these prepared arteries commenced without delay.

Measurement of agonist binding affinity and receptor occupancy.

The 5-HTR dissociation constants were determined using the Furchgott method of partial irreversible blockade (14) with the alkylating agent phenoxybenzamine (50–150 nM), as previously described (20, 45). Using this method, pairs of artery segments were pretreated with the PKG activator 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)guanosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate (8-pCPT-cGMP) across a range of concentrations from 0 to 30 µM to determine the influence of PKG. The final concentration of phenoxybenzamine was chosen to achieve a 50% decrease in 5-HT efficacy with a 30-min incubation. Pairs of adjacent phenoxybenzamine-treated and untreated artery segments were then assayed to obtain concentration-response curves used to prepare double-reciprocal plots of 1/[A] vs. 1/[A′] (where A represents agonist) over a concentration range of 10−10−10−4 M 5-HT. From these, an association constant for the 5-HTR complex (Ka) was taken as slope – (1/intercept). Using this, a fractional receptor occupancy ([RA]/[RT]) was calculated using the method described by Parker and Waud (36), where [RA]/[RT] = [A]/([A] + Ka). Here, [RA] represents the concentration of the receptor-agonist complex and [RT] is the total receptor concentration.

PKG abundance and activity.

MCA segments were homogenized using glass-on-glass mortars and pestles in 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 2 mM magnesium acetate, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 520 μM 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF), 7.5 μM pepstatin-A, 7 μM E64, 20 μM bestatin, 100 μM leupeptin, and 0.4 μM aprotinin. Supernatants were collected after centrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C and analyzed for protein content using the Bradford assay, as previously described (3). Aliquots were then divided for separate analysis of PKG abundance by Western blot and PKG activity. Relative abundances of PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ isoforms were determined using SDS-PAGE separation and visualized using methods previously described in detail by our laboratory (44). Relative abundances of total PKG were normalized to standards prepared from arteries harvested from adult normoxic nonpregnant ewes. PKG activity was determined using aliquots of supernatants from the above homogenates (44). Briefly, samples were incubated for 30 min, added to a homogenizing reaction buffer in 96-well plates containing [γ-32P]ATP (Nen Life Science), the PKG substrate BPDEtide (200 μM, BMLP-112-0001, Enzo Life Sciences), and 8-pCPT-cGMP (10 µM). Timed reactions were terminated by the addition of phosphoric acid, and phosphorylated BPDEtide and unreacted [γ-32P]ATP were then separated using phosphocellulose filter paper. Washed filters were added to vials with a scintillation cocktail and assayed using a liquid scintillation counter. Counts were converted into picomoles of 32P using a calibration curve that was produced concurrently with the samples and normalized to sample protein content to obtain PKG activity, expressed as picomoles of 32P transferred per minute per milligram of protein. Each assay included controls using 1) no added 8-pCPT-cGMP, 2) no added BPDEtide substrate, and 3) neither 8-pCPT-cGMP nor BPDEtide to correct for total nonspecific background.

BK channel protein abundance.

MCAs from fetal and newborn sheep were harvested, debrided, rapid-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Tissues were subsequently homogenized using glass-on-glass in radioimmunoprecipitation assay extraction buffer containing 10 mM DTT and a protease inhibitor cocktail (M-1745, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). Samples were centrifuged at 5,000 g for 20 min, and supernatants were then collected and analyzed using SDS-PAGE along with reference control samples from pregnant adult sheep MCAs. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes at 200 mA for 90 min in Towbin buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, and 20% methanol). Membranes were blocked using 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline at pH 7.45 (M-TBS) for 1 h at room temperature with continuous shaking. Primary antibodies were incubated for 12 h at 4°C using the following dilutions: BKα, 300:1 (APC-021, Alomone, Jerusalem, Israel), and BKβ1, 300:1 (APC-036, Alomone). For visualization, membranes were incubated for 90 min with a secondary antibody conjugated to DyLight 800 (no. 46422, Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). Subsequently, membranes were stripped and reprobed using antibodies against β-actin (monoclonal anti-β-actin produced in mouse, clone AC-74, A-2228, Sigma-Aldrich) as a loading control. Anti-β-actin was diluted using a factor of 1:5,000 and incubated for 90 min in M-TBS buffer with 0.1% Tween 20. Membranes were imaged on Li-Cor Bioscience’s Odyssey system, and individual protein bands were quantified using Li-Cor Image Studio software. Protein abundance was normalized using β-actin as a loading control and expressed as a relative abundance compared with an arbitrary reference standard (pooled whole cell lysate obtained from adult sheep MCAs).

5-HT concentration response.

Denuded ovine MCAs were cut into segments of ~3 mm in length, mounted on tungsten wire loops, suspended from a force transducer in a sodium Krebs buffer solution (pH 7.4) at 38°C (ovine core temperature), and bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. l-NAME (100 µM) and l-NNA (100 µM) were added to the Krebs buffer solution to inhibit endogenous NO production and sGC activation. To selectively inhibit activation of α1-adrenergic receptors by 5-HT and synaptic uptake of 5-HT, 1.0 µM prazosin and 0.2 μM cocaine were added, respectively. In preliminary experiments, both endothelium-intact and endothelium-denuded segments were studied. Removal of the endothelium did not affect contractile efficacy but reduced its variability; therefore, further experiments were performed using endothelium-denuded segments. The denuded segments were equilibrated for 30 min and then stretched to a baseline tension of 0.75 g (fetal) or 1.5 g (adult), which corresponded with an optimal stretch ratio of ~1.8 times the unstressed diameter. Contractile force was measured directly using an isometric force transducer (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) and recorded directly by computer in real time using a LabView-based instrument interface. Concentration-response curves were obtained by cumulative addition of half-log concentrations of 5-HT across a range of 10−10−10−4 M. In these experiments, 5-HT was the contractant of choice, in part because it was previously validated in our laboratory (43) and because preliminary experiments using norepinephrine showed it to be significantly less potent, less efficacious, and more variable than 5-HT in producing contractions in cerebral VSM; therefore, all further experiments were performed using 5-HT. EC50 values (molar concentration at which the contractile response was half the maximal induced contraction) were expressed as pD2 values (−log EC50). All contractile responses were normalized to the maximum force produced by exposure to K+-Krebs solution containing (in mM) 5.17 NaCl, 25.6 NaHCO3, 122 KCl, 2.49 MgSO4, 1.60 CaCl2, 2.56 dextrose, and 0.027 EGTA. To measure the relative contribution of BK (KCa1.1) channels to 5-HT contractions, concentration-response experiments were performed in the presence or absence of the selective BK channel blocker iberiotoxin at a concentration (100 nM) that previous work has shown to be optimal (42). Iberiotoxin was added to the baths in both the presence and absence of 30 µM 8-pCPT-cGMP 20 min before the concentration-response measurements were started.

Confocal imaging microscopy.

Fetal and adult hypoxic and normoxic MCAs were harvested, debrided, and sectioned into 3-mm segments. Segments were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and then transferred to PBS until further processing. Fixed artery segments were then embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-µm sections, and mounted onto glass slides for immunohistochemistry processing and staining. BKα protein was labeled using a primary antibody [rabbit polyclonal (APC-021, Alomone) or goat polyclonal (catalog no. SC-14747, Santa Cruz Biotechnology)] and then counterstained using a fluorescent-tagged secondary antibody, donkey anti-rabbit (Alexa fluor 633, catalog no. NPB1-75638, Novus Biologicals) or donkey anti-goat (Alexa fluor 488, catalog no. A-11055, Thermo Fisher Scientific). BKβ1 protein was labeled using a primary antibody (SC-14749, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and counterstained using a fluorescent-tagged secondary antibody, donkey anti-goat (488 nm, catalog no. A-21206, Thermo Fisher Scientific). PKGα protein was labeled using a primary antibody specific for a 100-amino acid NH2-terminal epitope (rabbit polyclonal, catalog no. ADI-KAP-PK-005-F, Enzo Life Sciences) and counterstained using a fluorescent-tagged secondary antibody, donkey anti-rabbit (same as above). RyR protein was labeled using a primary antibody, which detects all three known isoforms (RyR-1, RyR-2, and RyR-3) in mammalian tissues (mouse monoclonal, catalog no. MA3-925, Invitrogen), and counterstained using a fluorescent-tagged secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse (catalog no. A-11001, Invitrogen). Stained tissues were illuminated at 488 nm with a krypton-argon laser and at 633 nm with a helium-neon laser. The emitted light was collected using a photomultiplier tube with a band-limited spectral grating in the range 500–600 nm for Alexa fluor 488 images (peak excitation/emission: 496/519 nm) and 600–700 nm for Alexa fluor 633 images (peak excitation/emission: 632/647 nm). Images were acquired using an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope and using Olympus FluoView imaging software (Olympus Scientific Solutions, Waltham, MA).

Determination of protein colocalization: quadrant analysis.

Images that were acquired using confocal microscopy were analyzed to determine protein colocalization using Colocalizer Pro software (CoLocalization Research Software). These tagged image file format (TIFF) images contained separate plates for each fluorochrome, and thus each separate protein of interest, as well as a merged image that artificially appeared as yellow and represented a spatial colocalization of the two proteins within each separate voxel [146 × 146 × 545 nm at 488 nm (green) and 185 × 185 × 693 nm at 633 nm (red)]. Although this colocalization did not prove a functional relationship, it did provide a solid quantitative basis for any potential cooperativity between any two given proteins. Individual red and green pixels from these images were separately quantified and plotted on a two-dimensional grid (Fig. 7A). Background noise intensities were removed using a 12% (31/255 instrument range) threshold on both axes, based on the pixel intensity distribution of control samples and apparent population boundaries. High- and low-intensity thresholds were set at 50% (128/256 instrument range) for both red and green axes based on a median population distribution of a set of reference control samples. This 50% high-low threshold was maintained consistently throughout all subsequent analyses. The two-dimensional distribution and the 50% threshold boundaries thus defined a four-quadrant grid (see grid at bottom left of Fig. 7B). Given that voxel dimensions for the separate wavelengths were not identical, this presents a volume accessible to the longer wavelength (red) that is not accessible to the shorter wavelength (green). To eliminate this bias, we limited the analysis to only colocalized pixels above the 12% threshold for both markers. Pixels where one or both wavelength signal intensities were below the 12% threshold were not considered in the analysis. Thus, the sum of all colocalized pixels above the 12% threshold represents a denominator for calculating the relative fraction of colocalized pixels in each representative quadrant for each study group [fetal normoxic (FN), fetal hypoxic (FH), adult normoxic (AN), and adult hypoxic (AH)]. Quadrant 1 (Q1) represented the fraction of pixels with simultaneous high red and high green intensities. Likewise, quadrants 2 and 4 (Q2 and Q4) represented low green/high red and high green/low red, respectively. Quadrant 3 (Q3) was low intensity on both axes. Using this approach, separate images were analyzed for each protein pair of interest (BKα with BKβ1, PKG with BKα, and PKG with BKβ1).

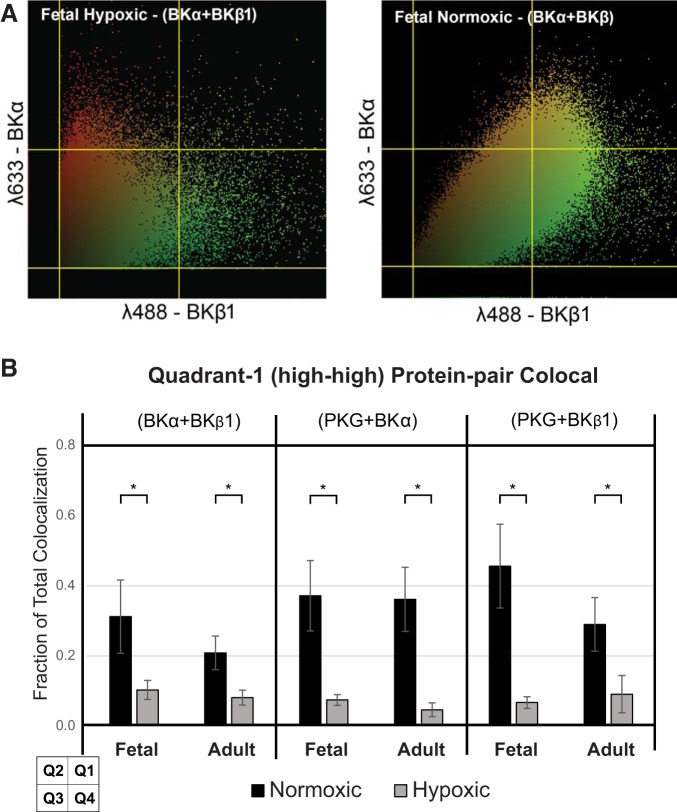

Fig. 7.

Quadrant analysis. A: representative scattergrams for fetal normoxic and hypoxic middle cerebral arteries illustrate a substantial loss of protein colocalization secondary to chronic hypoxia. Likewise, each of the six protein pairs exhibited qualitatively similar scattergrams (not shown). For the protein pair shown (BKα with BKβ1, fetal normoxic and hypoxic), the vertical axis (λ633, red) represents BKα and the horizontal axis (λ488, green) represents BKβ1 across the full resolution (intensities 0–255) of the analysis software. B: quadrant 1 (Q1; top right in each scattergram) colocalization expressed as a fraction of the total shows that chronic hypoxia had a significant effect on all three protein pairs (BKα with BKβ1, PKG with BKα, and PKG with BKβ1) in both fetal and adult arteries. Age (fetal vs. adult) displayed a modest but not significant trend in colocalization of BKα-with-BKβ1 and PKG-with-BKβ1 protein pairs in normoxic cerebral arteries (black bars). Age had no significant effect on colocalization of these protein pairs among hypoxic arteries (gray bars). *Significance (P < 0.05).

Determination of protein proximity index.

A protein proximity index (PPI) was calculated for each protein pair of interest using the method described earlier by Zinchuk et al. (53) together with the Protein Proximity Analyzer software (PPA, kindly provided by the Department of Anesthesiology, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA). Each of the two methods (quadrant analysis and PPI analysis) used different algorithms for eliminating noise. Using PPI analysis, ratios of autocorrelation to cross-correlation parameters were taken as a measure of true protein-protein proximity within the boundaries of each voxel dimension (47). Noise was eliminated by an algorithm that recognized a “slow-decay” surface on a three-dimensional mesh plot. Calculated PPI values for each protein pair were represented wherein each protein appeared in the denominator separately, in a manner reminiscent of classical Mander’s correlation coefficients, e.g., [P1 + P2]/P1TOT, and [P1 + P2]/P2TOT, where [P1 + P2] represents the colocalized protein signal within a given quadrant and P1,2TOT represents the total protein signal for a given wavelength above the 12% threshold. In ideal conditions where statistical noise and pseudocolocalization were perfectly eliminated, the PPI would represent the actual ratio of colocalized protein.

Data analysis and statistics.

Significant differences in contractile variables were determined using Behrens-Fischer tests for two-group comparisons and ANOVA followed by Duncan’s post hoc simultaneous comparisons of >2 groups. Analyses using SPSS software (SPSS version 22, IBM, Armonk, NY) confirmed homogeneity of variance and normal data distributions in all reported data sets. Determinations of binding affinity (pKa) values were based on double-reciprocal plots from which slopes were determined by linear regression as described by Furchgott (14). Contractile forces were normalized relative to the contraction produced by exposure to isotonic 120 mM K2+-Krebs buffer in the same artery segment. The relative influence of PKG stimulation on the BK channel compared with all other downstream targets was estimated using an algebraic model introduced previously (44) where a is maximum response to 5-HT in control arteries (untreated), b is total maximum response to 5-HT in the presence of PKG stimulation by 8-pCPT-cGMP, c is maximum response to 5-HT in presence of iberiotoxin, and d is the maximum response to 5-HT in the presence of iberiotoxin and with pretreatment using 8-pCPT-cGMP. The total effect of PKG activation was defined as (a − b), and the effect of PKG activation independent of BK channel activity was defined as (c − d). The BK channel-dependent effect of PKG activation was calculated as (a − b) – (c − d). Maximum efficacy of 5-HT was calculated using SPSS and GraphPad (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) with a nonlinear regression model using the following four-parameter Hill equation for a concentration-response curve:

where e represents the estimated baseline response, f represents the estimate maximal response, g represents the agonist concentration that yields the half-maximal response, and h represents the Hill coefficient.

RESULTS

A total of 50 sheep were used in this study, of which 24 were term fetal lambs, including 13 that were from high altitude and 11 that were from low altitude, and 26 were adult sheep, of which 13 were from high altitude and 13 from low altitude. From these animals, we harvested a total of 272 MCA segments, including 132 fetal segments and 140 adult segments. A total of 104 segments were used for functional experiments to measure contractile force, and 168 segments were used for confocal imaging. Throughout the text, n represents the number of animals and not the number of segments used in each experiment. Statistical significance implies P < 0.05. All values are given as means ± SE.

Effects of hypoxia, age, and 8-pCPT-cGMP on 5-HT concentration-response relations.

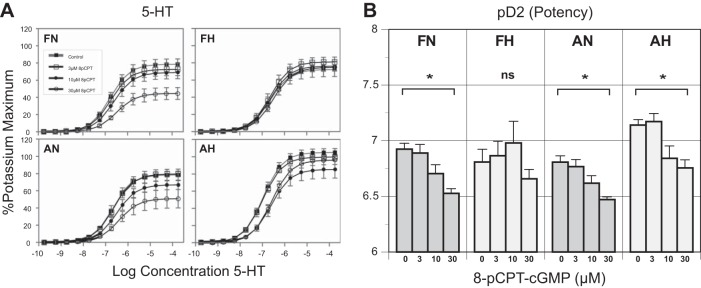

Hypoxia had a strong effect on the maximal vasorelaxation in response to treatment with graded concentrations of 8-pCPT-cGMP up to the maximum of 30 µM in both fetal and adult arteries (Fig. 1A, left). Hypoxia did not significantly affect the response to the maximal 5-HT concentration (Emax) in untreated fetal arteries (69.7 ± 3.8 normoxic vs. 77.2 ± 2.9 hypoxic; Fig. 1A, top) but had a modest effect in adult arteries (69.9 ± 16.8 normoxic vs. 96.7 ± 17.7 hypoxic; Fig. 1A, bottom). In contrast, age had a significant effect on Emax among hypoxic (77.2 ± 16.7 fetal vs. 96.7 ± 17.7 adult) but not normoxic (69.7 ± 24.1 fetal vs. 69.8.7 ± 16.8 adult) arteries (Fig. 1A, top vs. bottom). Loss of 8-pCPT-cGMP-dependent vasorelaxation potential among both hypoxic fetal and adult arteries was the main finding of this experiment. Owing to the robust response to 30 µM 8-pCPT-cGMP, this concentration was used in subsequent experiments throughout.

Fig. 1.

Effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP and hypoxia on 5-HT potency and concentration-response relations. A: pretreatment with graduated concentrations of 8-pCPT-cGMP determined the optimal concentration for investigating attenuation of vascular tone in ovine middle cerebral arteries. This approach demonstrated that hypoxia attenuated 5-HT-induced contraction in both fetal and adult arteries at the optimal concentration of 30 µM. B: adult hypoxic arteries exhibited modestly greater contractile responses and 5-HT potency compared with normoxic arteries. Increasing 8-pCPT-cGMP concentrations significantly attenuated 5-HT potency in all but the fetal hypoxic arteries. FN, fetal normoxic; FH, fetal hypoxic; AN, adult normoxic; AH, adult hypoxic. *P < 0.05. ns, Not significant.

Effects of hypoxia, age, and 8-pCPT-cGMP on 5-HT agonist potency.

The potency (pD2 or −log EC50) of 5-HT was significantly and similarly attenuated by 8-pCPT-cGMP in both fetal and adult arteries (Fig. 1B). Hypoxia increased the pD2 values for 5-HT in untreated adult but not fetal arteries. Correspondingly, 8-pCPT-cGMP did not significantly affect 5-HT pD2 values in hypoxic fetal arteries but significantly decreased these values in hypoxic adult arteries (Fig. 1B). The 5-HT pD2 values were similar in untreated normoxic fetal and adult arteries but were significantly less in untreated hypoxic fetal than in hypoxic adult arteries (6.8 ± 0.3 fetal vs. 7.2 ± 0.13 adult).

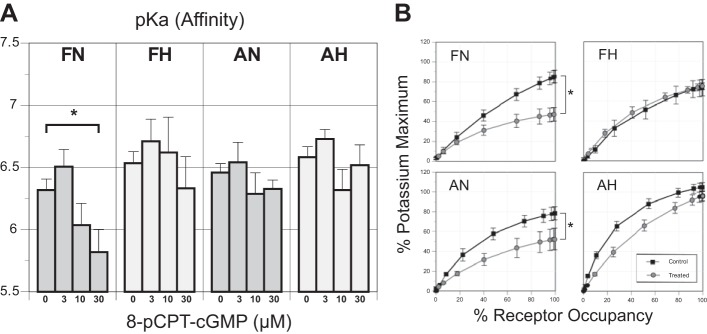

Effects of hypoxia, age, and 8-pCPT-cGMP on 5-HT receptor binding affinity.

Values for 5-HT binding affinity (pKa) as a function of 8-pCPT-cGMP concentration were significantly altered only in normoxic fetal arteries (6.32 ± 0.23 untreated vs. 5.82 ± 0.49 at 30.0 µM 8-pCPT-cGMP treated; Fig. 2A, first panel). Long-term hypoxia attenuated this depressant influence of 8-pCPT-cGMP on 5-HT binding affinity in fetal arteries. Adult arteries were unaffected by hypoxia with regard to any influence of 8-pCPT-cGMP on 5-HT binding affinity.

Fig. 2.

Effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP and hypoxia on occupancy-response relations for 5-HT. A: 5-HT receptor affinity (pKa) was determined for each experimental group using the Furchgott method. The 5-HT concentration-response relations were converted to occupancy-response relations using pKa values to correct for differences in agonist binding affinity. *P < 0.05. B: the resulting occupancy-response relations revealed that compared with untreated control arteries, pretreatment with 30 µM 8-pCPT-cGMP significantly reduced maximum efficacy for 5-HT in normoxic (left) but not hypoxic (right) arteries from both age groups. *Significant differences (P < 0.05, repeated-measures ANOVA) between untreated and treated (30 µM 8-pCPT-cGMP) arteries. Error bars indicate means ± SE for n ≥ 5 for all groups.

Effects of hypoxia, age, and 8-pCPT-cGMP on 5-HT receptor occupancy-response relations.

To correct for the observed differences in 5-HT receptor binding affinity, particularly with fetal arteries, the concentration-response relations for 5-HT were converted to occupancy-response relations by the method described by Parker and Waud (36) and using the experimentally determined pKa values (Fig. 2A). Any differences attributable solely to the effects of hypoxia on receptor affinity were fully compensated by this correction for receptor occupancy. In the converted occupancy-response curves, the effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP on contractile responses persisted in normoxic arteries but were still attenuated in hypoxic arteries, indicating that the observed changes in the influence of 8-pCPT-cGMP on vasorelaxation involved effects independent of changes in receptor binding affinity and that hypoxia acted downstream from the 5-HT receptor-binding event. The 8-pCPT-cGMP-induced decrease in contractile responses to 5-HT as a function of receptor occupancy was significant in both fetal and adult normoxic arteries (38.0 ± 12.1 and 26.05 ± 9.7, respectively; Fig. 2B, left); whereas in hypoxic arteries, induced vasorelaxation was not significantly different compared with controls (−1.4 ± 10.2 and 8.9 ± 7.0, respectively; Fig. 2B, right) at maximum receptor occupancy.

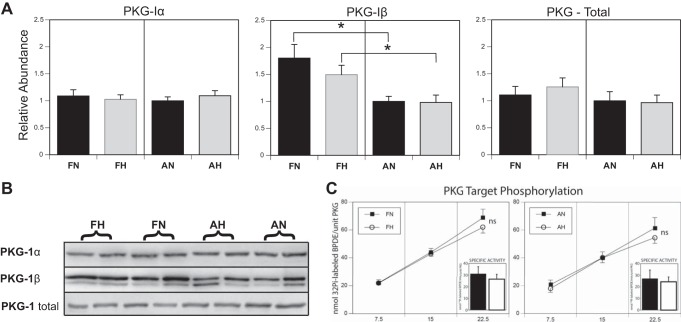

Effects of hypoxia and age on PKG abundance and specific activity.

PKG-I exists in two splice variant isoforms, designated PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ. Total PKG was determined by Western blot using an antibody that recognized a common epitope. Relative abundances were further normalized to adult normoxic values (AN = 100%) to emphasize similarities and differences in protein expression. Total PKG abundance showed only slight and nonsignificant variation among the four study groups (FN, FH, AN, and AH), as did the PKG-Iα isoform (Fig. 3A). The PKG-Iβ isoform was significantly more abundant in fetal compared with adult arteries but was not significantly affected by LTH. Although the fetal PKG-Iβ isoform was of higher abundance compared with adult arteries, the influence of PKG-Iβ on total PKG abundance was minimal, implying that it was of lower overall abundance compared with PKG-Iα and contributed less to the measure of total PKG expression.

Fig. 3.

PKG isoforms. A and B: abundance of total PKG was determined by Western blot analysis using an antibody against a PKG-I epitope common to both the Iα and Iβ isoforms. All abundances were calculated relative to known amounts of a standard pool prepared from normoxic adult arteries. Each gel included lanes with seven standards ranging from 1.0 to 15.0 µg and two samples for each of the four groups: normoxic fetal, hypoxic fetal, normoxic adult, and hypoxic adult. This approach evenly balanced the effects of gel-to-gel variation among all the experimental groups. B shows a group of contiguous unknown bands taken from a single gel-membrane image, for each antibody used. Relative abundance of PKG-Iβ was significantly (*P < 0.05) greater in fetal than adult arteries but was not affected by hypoxia. C: whole artery PKG activity in middle cerebral arteries (line graphs, pmol Pi/unit PKG) was not significantly affected by hypoxia in either fetal (left) or adult (right) homogenates. When whole artery PKG activity was normalized relative to PKG abundance (insets), estimates of specific activity (pmol Pi/min/unit PKG) did not vary significantly with hypoxia or between fetal and adult artery homogenates. These data indicate that the ability of hypoxia to ablate the effects of PKG on 5-HT contractions was not due to changes in PKG abundance or kinase activity. Error bars indicate means ± SE for n ≥ 6.

Whole artery PKG activity was unaffected by age (fetal vs. adult) or by LTH. The timed kinetic assay showed no significant differences in kinase activity, expressed as nanomoles of 32Pi-labeled BPDEtide per unit PKG (Fig. 3C). The kinetic rates (specific activity) were likewise nearly identical among the four study groups (AN, FH, AN, and AH), expressed as nanomoles of 32Pi-labeled BPDE per minute per unit PKG. Importantly, any differences in PKG abundances as previously measured (above) were not reflected in their functional kinase activity. Neither PKG abundance nor activities were able to account for hypoxic attenuation of PKG-induced depression of contractile responses to 5-HT.

Interactive effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP and iberiotoxin on 5-HT-induced contraction.

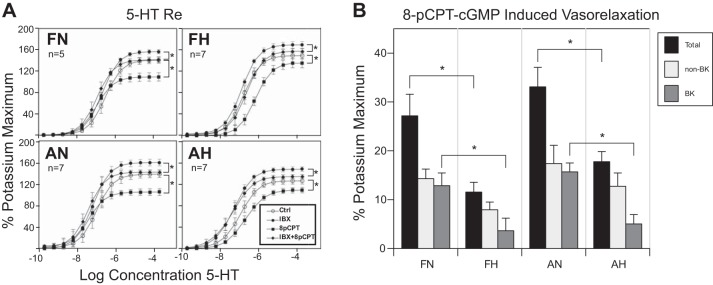

Treatment of arteries with 8-pCPT-cGMP significantly attenuated 5-HT efficacy in all study groups (Fig. 4A, control vs. 8-pCPT-cGMP). Pretreatment with iberiotoxin alone increased 5-HT efficacy in all arteries, but the addition of 8-pCPT-cGMP to iberiotoxin-treated arteries demonstrated a persistent but diminished vasorelaxation, indicating a significant component of non-BK channel-mediated vasorelaxation (Fig. 4A, iberiotoxin vs. iberiotoxin + 8-pCPT-cGMP). The relative contributions of BK channel- versus non-BK channel-mediated vasorelaxation were quantified using our algebraic model. This showed that in hypoxic arteries the BK-independent component had a small but not significant attenuation. In contrast, BK-dependent PKG-mediated vasorelaxation was strongly reduced in both fetal and adult arteries (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Concentration-response relations for 5-HT. A: effects of iberiotoxin, 8-pCPT-cGMP, age, and hypoxia on 5-HT concentration-response relations. Maximum contractile responses to graded concentrations of 5-HT varied moderately with age and hypoxia in untreated arteries. Maximum contractile responses in iberiotoxin-treated arteries were significantly greater in adult normoxic arteries compared with adult hypoxic arteries. Pretreatment with 30 µM 8-pCPT-cGMP significantly (*P < 0.05) attenuated 5-HT efficacy in a concentration-dependent manner in normoxic fetal and adult arteries. In arteries pretreated with 30 μM 8-pCPT-cGMP, 5-HT efficacy was greater in hypoxic compared with normoxic arteries for fetal but not adult arteries. Ctrl, control; IBX, iberiotoxin. B: vasorelaxation attributable to BK channel vs. non-BK channel vasorelaxation was determined using an algebraic model. Non-BK channel influence was of greater magnitude in all subgroups (FN, FH, AN, and AH), whereas BK channel effects were more sensitive to long-term hypoxia (LTH), particularly in fetal arteries. Error bars indicate means ± SE for n ≥ 6 for all groups. *Significance (P < 0.05).

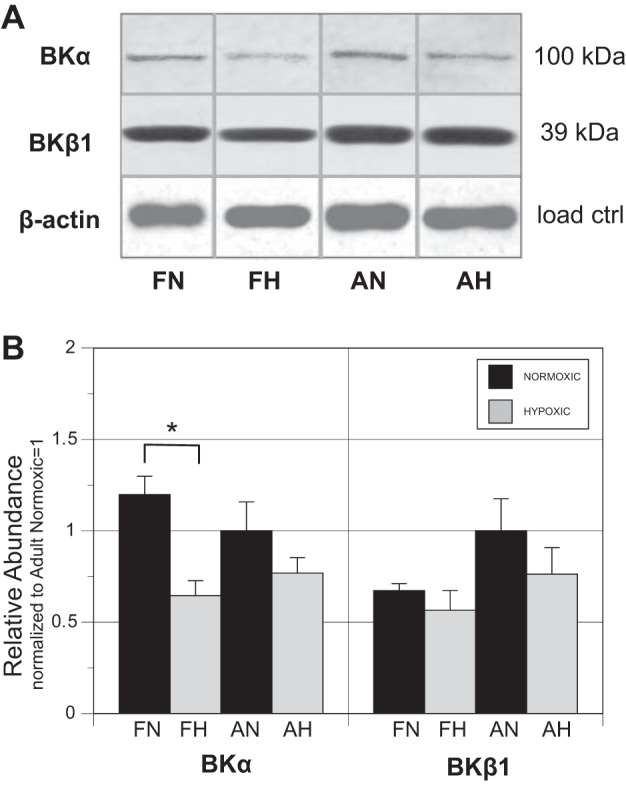

Effects of hypoxia and age on BK protein isoform abundance.

The abundance of BKα and BKβ1 was measured by Western blot (Fig. 5A). Across both age groups, ANOVA revealed a significant depression in abundance for BKα that was individually significant by Student’s t-test in fetal (1.20 ± 0.10 FN vs. 0.67 ± 0.08 FH, P < 0.02) but not adult (2.46 ± 0.51 vs. 1.89 ± 0.51, not significant) arteries (Fig. 5B). The effects of hypoxia on BKβ1 abundance were not significant in either age group.

Fig. 5.

BKα and BKβ1 isoforms. A: abundance of total BKα and BKβ1 isoforms was determined by Western blot analysis using an antibody against a specific epitope in both α- and β1-isoforms. B: all abundances were calculated relative to known amounts of a standard pool prepared from normoxic adult arteries. Relative abundance of BKα was significantly (*P < 0.05) attenuated (46%) by hypoxia in fetal cerebral arteries. Abundance of BKβ1 was not significantly influenced by chronic hypoxia. ANOVA showed a significant influence of hypoxia on fetal BKα abundance but no significant interactions of age with hypoxia for either BKα or BKβ1 protein abundances. Error bars indicate means ± SE for n ≥ 6.

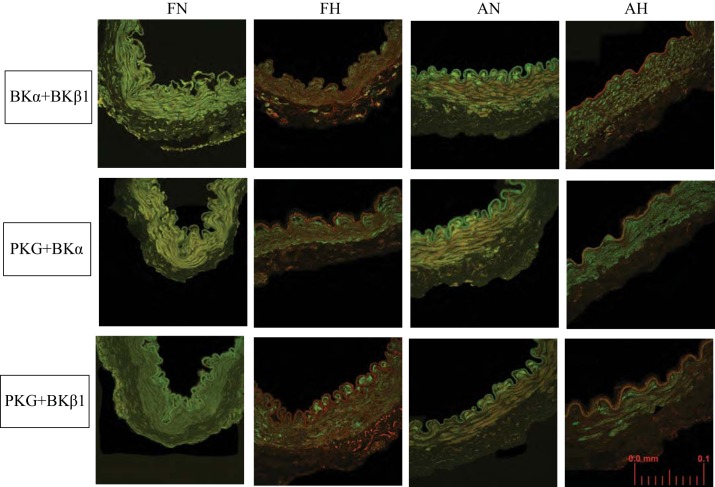

Effects of hypoxia and age on protein colocalization.

Visual inspection of merged confocal images provided insight into the extent and magnitude of protein colocalization between PKG and BK subunits, where red or green represented individual proteins of interest and yellow shades (artificially) represented a spatial convergence of separate red and green pixels (Fig. 6). Normoxic artery images among all four study groups, and for each of the three protein pairs, contained noticeably more yellow-shaded pixels within the medial layer compared with their hypoxic counterparts. Representative scattergrams for fetal normoxic and hypoxic middle cerebral arteries demonstrated a substantial loss of protein colocalization secondary to LTH (Fig. 7A). “Colocalization” in this context was defined as a concurrency of two separate proteins within the confines of each voxel interrogated. This defined a linear separation range of 0–583 nm, i.e., the extreme corners of each individual rectangular 146 × 146 × 545-nm voxel. Each of the six protein pairs examined showed qualitatively similar scattergrams (not shown). For the protein pair BKα with BKβ (Fig. 7A), the vertical axis [wavelength of 633 nm (λ633), red] represented BKα, and the horizontal axis (λ488, green) represented BKβ1 across the full resolution (intensities of 0–255) of the analysis software. Q1 (high BKα, high BKβ1) was nearly depleted of colocalized pixels in the fetal hypoxic panel. Q1 colocalization expressed as a fraction of the total revealed that LTH significantly affected all three protein pairs (BKα with BKβ1, PKG with BKα, and PKG with BKβ1) in both fetal and adult arteries (Fig. 7B, histogram). Age (fetal vs. adult) displayed a modest but not significant effect on colocalization of BKα with BKβ1 and PKG with BKβ1 in normoxic cerebral arteries. Age had no significant effect on colocalization of any protein pairs among hypoxic arteries.

Fig. 6.

Confocal microscopy. Top panels represent the distribution of BKα protein (red) and BKβ1 protein (green). The merged images appear as shades of yellow where the two proteins are colocalized within the resolution of the acquired images. Voxel dimensions were ≈146 × 146 × 545 nm at 488 nm (red) and ≈185 × 185 × 693 nm at 633 nm (green). Hypoxic artery segments in both fetal and adult arteries appeared visibly less yellow and thus represented less colocalization in that protein pair. Middle panels represent PKG (red) and BKα (green). These merged images likewise appeared visually to possess less colocalized protein for both fetal and adult hypoxic arteries. Bottom panels represent PKG (red) with BKβ1 (green) protein. Images represent a field of ~180 × 180 µm (scale, bottom right panel). Histological changes in the hypoxic arteries were also apparent; the medial layer was thinner and less invested in fusiform cell morphology, suggesting a probable shift in smooth muscle phenotype.

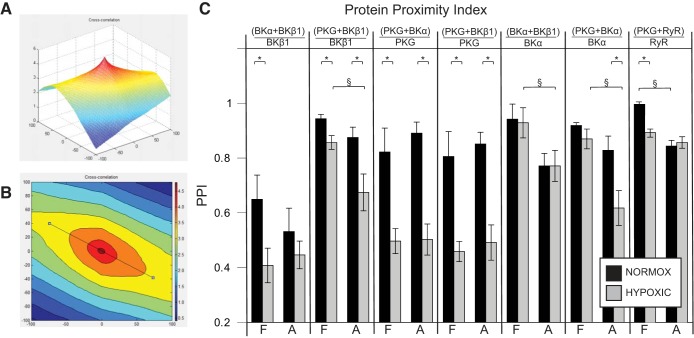

A calculated PPI using these same images corroborated the results from the above quadrant analysis (Figs. 8, A and B). A histogram of PPI results (Fig. 8C) likewise showed that LTH significantly depressed colocalization of BKα with BKβ1 as a ratio of total BKβ1 protein [(BKα + BKβ1)/BKβ1] in both fetal and adult arteries (Fig. 8C, first panel). LTH also depressed [(PKG + BKα)/PKG] and [(PKG + BKβ1)/PKG] PPI in both fetal and adult arteries (Fig. 8C, third and fourth panels). LTH had less influence on the PPI of BKα colocalized with BKβ1 expressed as a ratio to total BKα [(BKα + BKβ1)/BKα] (Fig. 8C, fifth panel). However, maturity had a small but significant influence on [(PKG + BKβ1)/BKβ1] PPI as well as [(BKα + BKβ1)/BKα)] and [(PKG + BKα)/BKα] indexes among LTH but not normoxic arteries (Fig. 8C, second, fifth, and sixth panels).

Fig. 8.

Protein proximity index (PPI). A: a three-dimensional mesh plot depicting the cross-correlation surface from an adult normoxic artery image stained for BKα and BKβ1. The horizontal scales represent a measure of Gaussian shift ±100 units from the peak intensity; the vertical scale represents signal intensity. The slow-decay portion of this surface (blues and yellows) represents a pseudocorrelation subset and was filtered from further analysis. The rapid-decay surface (oranges and reds) represents presumed protein-protein interactions (53). This cross-correlation surface, plus the autocorrelation surface for each individual protein of interest (not shown), provides a basis for computing the PPI. B: contour plot from the same data as above, showing the “slice” (straight black line) that defines a cross section for purposes of equation fitting of the grid data. The cross section always bisects the peak of each mesh plot and includes the rapid-decay surface. C: this PPI histogram shows that LTH significantly (*P < 0.05) depressed colocalization of BKα with BKβ1 as a ratio of total BKβ1 protein [(BKα + BKβ1)/BKβ1] in both fetal (F) and adult (A) arteries (1st panel). LTH also depressed the [(PKG + BKα)/PKG] and [(PKG+ BKβ1)/PKG] PPI in both fetal and adult arteries (3rd and 4th panels). LTH had less influence on the PPI of BKα colocalized with BKβ1 expressed as a ratio to total BKα [(BKα + BKβ1)/BKα] (5th panel). Age showed a small but significant (§P < 0.05) influence on the [(PKG + BKβ1)/BKβ1] PPI as well as the [(BKα + BKβ1)/BKα] and [(PKG + BKα)/BKα] indexes among hypoxic but not normoxic arteries (2nd, 5th, and 6th panels). Values of the PPI for [(PKG + RyR)/RyR] were significantly greater in normoxic fetal than normoxic adult arteries (§P < 0.05) and were significantly depressed by chronic hypoxia in fetal (*P < 0.05) but not adult arteries.

Values of PPI calculated for colocalization of PKG with the RyR in cerebral arteries revealed that colocalization was significantly greater in normoxic fetal than in normoxic adult arteries (Fig. 8C, seventh panel). In addition, chronic hypoxia significantly depressed colocalization of PKG with the RyR in fetal but not adult cerebral arteries.

DISCUSSION

This study on the effects of long-term hypoxia in endothelium-denuded ovine cerebral arteries offers five main observations: 1) the PKG influence on 5-HTR affinity was diminished with LTH, but this represented only a minor effect; 2) activation of PKG to induce vasorelaxation was significantly less effective in both fetal and adult LTH-acclimatized cerebral arteries; 3) PKG abundance and specific activity were unaffected by LTH; 4) BK channel protein abundances were modestly downregulated with LTH, BKα more than BKβ1, and fetal more than adult; and 5) structural organization of key vascular proteins was strongly affected by LTH and may have accounted partially for the observed functional loss of PKG-mediated vasorelaxation. These studies build on our previous work by demonstrating hypoxic changes in BK subunit abundances in fetal cerebral arteries and through introduction of the use of advanced methods of confocal colocalization to study interaction between PKG and its targets.

The role of the vascular endothelium and NO pathway as a mediator of vasorelaxation has been well studied. This work has consistently shown that the role of the endothelium as a master regulator of vascular tone is reliant on PKG within smooth muscle, which serves as the main end effector of this pathway. Previous work in carotid arteries (44) has shown that a substantial component of the loss of PKG influence after hypoxic adaptation occurs independently of the endothelium and NO pathway. Of greater clinical importance are the hypoxic adaptations within cerebral arteries, and cerebrovascular VSM in particular. To this end, we set about to directly examine the role of PKG, as well as those of its target proteins, to identify specific mechanisms responsive to hypoxic stress. As a first approach, completion of 5-HT concentration-response experiments yielded insights into the contractile effects of PKG activation under varying conditions of O2 availability and developmental maturity.

Influence of PKG on 5-HTR binding and coupling.

The 5-HT2 receptor (5-HT2R) is a member of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily (10). Phosphorylation of the 5-HT2R by cyclic nucleotide-dependent kinases and G protein receptor kinases (GRKs) can promote binding of β-arrestins that influence receptor behavior including agonist binding affinity and intracellular coupling (19, 32). Furthermore, affinity is biologically regulated, which establishes a rationale for examining effects of PKG on pKa (31). These experiments demonstrated an influence of PKG on 5-HT2R ligand binding affinity, albeit of low magnitude (Fig. 2A). However, the observed efficacy of 5-HT is a product of binding affinity (pKa), membrane receptor density, and coupling efficiency. To correct for variations in observed 5-HT2R affinity, we converted 5-HT concentration-response curves to receptor occupancy curves. If the loss of PKG-induced vasorelaxation, which was prominent in hypoxic arteries (Fig. 1), was attributable to alterations in receptor binding affinity, this correction would abolish the effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP on 5-HT-induced contraction. In contrast, the effects of PKG persisted (Fig. 2B), indicating that the effects of hypoxia on PKG-mediated inhibition of vasoconstriction were predominantly downstream from the 5-HTR-binding event. This raised a more obvious question: could changes in PKG abundance or activity account for the observed loss of its influence in LTH acclimatized arteries?

Effects of hypoxia on PKG abundance and specific activity.

Differentiated VSM expresses PKG predominantly as two splice variant isoforms: PKG-Iα and PKG-Iβ, which exclusively express the first (1α) or second (1β) coding exon of the PRKG1 gene (35). Because only the PKG-Iα isoform typically is associated with regulation of cytosolic Ca2+ and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (2, 16), the observed minor variations in PKG-Iβ abundance (Fig. 3) probably had little influence on the vasorelaxant effects of 8-pCPT-cGMP, suggesting that changes in overall PKG abundance could not account for the observed loss of PKG-mediated inhibition of contraction in LTH-adapted arteries. Given that PKG has multiple phosphorylation sites that influence its catalytic activity (13), it was conceivable that LTH could influence PKG specific activity independent of its abundance. However, measurement of PKG total and specific activity revealed no significant effects of LTH in either fetal or adult arteries (Fig. 3C). Because neither PKG abundance nor activity were altered by LTH, the focus of this study next shifted to identification of one or more PKG substrates that might be altered by LTH.

Effects of LTH on 8-pCPT-cGMP-mediated attenuation of 5-HT-induced contraction.

Prominent among PKG substrates is the BK channel, which has a major role in mediating vasorelaxation (25). Pretreatment with iberiotoxin, a BK channel antagonist, can identify the influence of the BK channel apart from the collective non-BK channel components of vasorelaxation (8, 17, 48). We have previously used this principle to develop an algebraic model that can quantify the relative importance of the BK channel in PKG-mediated vasorelaxation (44). When we used this approach with LTH-acclimatized MCAs, two main observations emerged. First, PKG activation induced significant vasorelaxation in both normoxic and hypoxic arteries from both fetuses and adults, but the magnitude of this effect was strongly diminished in hypoxic arteries only (Figs. 4, A and B). Second, iberiotoxin revealed that hypoxia independently downregulated both BK channel- and non-BK channel-mediated components of vasorelaxation but had considerably more influence on the BK component. Given the demonstrated importance of the BK channel in mediating vasorelaxation, and its sensitivity to hypoxia, our experimental approach next determined whether LTH-mediated decreases in BK channel protein abundances might help explain hypoxic inhibition of PKG-induced attenuation of 5-HT contractions.

Moderate effects of hypoxia on BK channel protein abundances.

While the observed hypoxic decreases in BKα abundance might contribute to the observed loss of PKG regulatory influence, especially in fetal hypoxic arteries, the magnitude of this decrease was not proportional to the magnitude of the loss of vasorelaxation secondary to hypoxia (Fig. 4B). This suggested that alterations in BK protein expression may influence vascular responses to PKG activation after LTH acclimatization, but these decreases were probably not the dominant effect of LTH, particularly in adult arteries. Other possible effects of LTH on the vascular influences of PKG independent of PKG activity include changes in its trafficking and subcellular localization as well as the proximity and affinity for possible substrates. For example, PKC has been shown to influence the ability of PKG to recognize, bind, and then phosphorylate BKα protein (52). How LTH modulates the vascular influences of PKG through changes in its trafficking and subcellular organization remains largely unstudied. To gain insights into the possible effects of LTH on cellular protein organization, we next examined the structural-spatial relations of PKG with BK channel proteins using confocal microscopy.

Effects of LTH on the cellular organization and confocal colocalization of vascular proteins.

Homogenization of vascular tissue for the purpose of measuring kinase activity disrupts protein organization, scaffolding, and protein-protein relationships that may be essential for in vivo behavior. To explore the importance of physiological conditions that might reflect vascular adaptation to LTH, we measured in whole arteries the structural proximity of four highly interactive proteins that govern vascular tone: PKG, BKα, BKβ1, and RyR. These proteins rely on direct contact and interactions to effect changes in vascular tone. PKG has a substrate recognition domain that mediates substrate binding and is distinct from its catalytic domain (13). Loss or diminution of direct contact between PKG and its target substrates predict a loss of kinase activity and function. Similarly, direct association of BKβ1 with its BKα counterpart within the plasmalemma increases Ca2+ sensitivity of the BK channel and increases K+ conductance (30). Loss of direct association of BKβ1 with BKα predicts a diminution of Ca2+ sensitivity and thus attenuation of channel function, hyperpolarization, and vasorelaxation. Although PKG does not directly phosphorylate BKβ1, PKG and Rho kinase can both phosphorylate Ras-related protein-11a (RAB11a), which promotes rapid trafficking of BKβ1 to the plasmalemma and binding to BKα (26). Alternatively, the BK channel is closely regulated by the activity of nearby ryanodine receptors, whose activity can also be modulated by PKG (18, 22, 24).

Our working hypothesis was that protein colocalization represents the potential for protein-protein interaction and therefore function. Correspondingly, any change in structural organization that results in a loss of colocalization should represent a loss of potential for protein-protein interaction and decreased function. To test this idea, we used confocal microscopy to measure protein colocalization and thereby estimate the potential for protein-protein interaction within the limits of voxel resolution (≈146 × 146 × 545 nm). Pairs of proteins tagged with 488-nm (green) or 633-nm (red) fluorochromes were visualized in separate confocal images and in merged images wherein coincident red and green pixels appeared yellow (Fig. 6). Owing to the functional dependence of the labeled proteins on close proximal relationships, we interpreted loss of colocalization to imply a loss of PKG function in LTH arteries. To this end, the extent of protein colocalization was quantified nonparametrically using quadrant analysis (5, 11) and parametrically by determination of PPI.

Quadrant analysis of colocalization between PKG, BKα, and BKβ.

To obtain a nonparametric analysis of colocalization, the experimental approach employed a quadrant analysis of confocal images as previously described (1, 12). Using this method, individual pixels were assigned to a quadrant on the basis of their separate red (low or high) or green (low or high) signal intensities. Pixels thus grouped were weighted equally; differences in signal intensities within a quadrant were not considered. The power of this analytic technique was most useful in visualizing and quantifying shifts between quadrants and changes in population distributions under varying conditions. For each of the protein pairs examined, the effect of LTH on MCAs showed a strong shift from Q1 (high red, high green) to Q3 (low red, low green), indicating a large reduction in colocalization of these proteins in response to hypoxic stress (Fig. 7). This was observed for both fetal and adult arteries; each of the normoxic-hypoxic contrasts for each of the six protein pairs shown in Fig. 7 were strongly significant, suggestive of an important structural reorganization in response to LTH. This finding was consistent with a reduced ability of PKG to depress contractile tone following LTH.

PPI analysis of colocalization for PKG with BKα, BKβ, and the RyR receptor.

To corroborate the above nonparametric quadrant analysis, we also performed a parametric PPI analysis using the same images used for the quadrant analysis. This approach enhanced the rigor of the colocalization analysis because the two methods relied on distinctly separate algorithms and underlying assumptions. As such, the PPI method was designed to be more sensitive to the full range of signal intensities and thus constituted a fully parametric analysis. The calculated PPI values revealed that chronic hypoxia caused a strong loss of colocalization in the majority of protein ratios examined (Fig. 8C) and largely corroborated the quadrant analysis. The PPI analysis also revealed that chronic hypoxia depressed colocalization between PKG and the RyR in fetal but not adult arteries, which helps explain why the magnitude of hypoxic attenuation of PKG-dependent attenuation of contractile tone was more pronounced in fetal than adult arteries (Figs. 1 and 2). Interestingly, hypoxic changes in the PPI ratio were most robust when the denominator values were associated with proteins, including PKG and BKβ1, which did not change in response to LTH. Overall, two quite distinct and independent analytical methods, quadrant and PPI analysis, supported a similar interpretation: LTH strongly attenuated colocalization among three highly interactive proteins that together governed the effects of PKG on vascular tone.

Perspectives and significance.

The present study addresses our hypothesis that hypoxia reduces the ability of PKG to attenuate vasoconstriction in part through suppression of the ability of PKG to associate and interact with BK channels in cerebrovascular smooth muscle. The experiments also addressed the corollary hypotheses that hypoxic inhibition of the vasorelaxant efficacy of PKG was due to 1) decreased PKG abundance, 2) decreased PKG catalytic activity, 3) decreased BK subunit abundance, 4) decreased colocalization of PKG with BK subunits, and 5) decreased colocalization of PKG with RyRs. This investigation revealed that acclimatization to long-term hypoxia depressed PKG-mediated attenuation of vasoconstriction in cerebral arteries through significant effects on BKα abundance and BKα/BKβ1/PKG colocalization with a modest age-dependent effect on colocalization between PKG and the RyR, suggesting a possible change in Ca2+ spark activity. In turn, these results predict that PKG-dependent phosphorylation of BK subunits would be depressed by chronic hypoxia. Preliminary measurements of PKG-dependent BK phosphorylation, measured by changes in phosphoserine immunoreactivity, are consistent with this prediction but require further study and verification, ultimately by mass spectrometry. The results also demonstrate that non-BK mechanisms were responsible for the majority of PKG-dependent relaxation in all groups examined but were generally less sensitive to hypoxia than BK-dependent mechanisms. Overall, loss of PKG-mediated attenuation of vasoconstriction after acclimatization to LTH appears to involve multiple factors, the most important of which is decreased interactions of PKG with its targets for phosphorylation. Correspondingly, the aggregate results predict a hypoxic loss of efficacy for therapeutic strategies reliant on the NO pathway for which PKG is the main end-point effector. These include exogenous NO, its precursors, and phosphodiesterase inhibitors, all of which are commonly prescribed. Hypoxic loss of PKG efficacy could potentially affect individuals acclimatized to chronic hypoxia, either by extended excursion to high altitude or by predisposing medical conditions that include perinatal hypoxic stress, such as maternal smoking, placental insufficiency, or lung disease. Treatment and management of these pathologies deserve further investigation, particularly in relation to therapeutic manipulation of the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway.

The analytic utility of confocal microscopy has evolved dramatically during the past decade, and an ever-growing armamentarium of new tools has facilitated novel insights into the important relations between protein organization and cell function. In the present study, the use of confocal microscopy helped demonstrate that three key proteins that govern cerebrovascular tone disengage spatially under conditions of LTH and that this loss of organization correlates strongly with attenuation of their known functions. These findings augment an emerging awareness in vascular biology of regulatory systems that rely on changes in molecular trafficking and dynamic subcellular organization. Although the present results strongly suggested hypoxic changes in vascular protein organization, the findings were limited by the voxel dimensions of the analyzed images, which were an order of magnitude larger than the size of the proteins being studied. Clearly, changes in colocalization alone do not definitively prove changes in direct protein interaction. Such proof will require higher-resolution measurements of protein-protein proximities by use of fluorescence resonance energy transfer, proximity ligation assays, or superresolution microscopy. Aside from these limitations, this present investigation introduces a new paradigm for hypoxic adaptation, namely, that apart from changes in abundance and phospho-status, changes in subcellular protein location, trafficking, and temporospatial relationships represent a dominant mechanism whereby chronic hypoxia regulates vascular reactivity, remodeling, and structure-function relations.

GRANTS

The work reported in this manuscript was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-54120, HD-31266, and HL-64867 and the Loma Linda University School of Medicine (LLUSM). Imaging was performed in the LLUSM Advanced Imaging and Microscopy Core with the support of National Science Foundation Grant MRI-DBI 0923559 and the LLUSM.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.B.T, J.M.W., and W.J.P. conceived and designed research; R.B.T., M.C.H., J.S., and J.M.W. performed experiments; R.B.T., J.M.W., and W.J.P. analyzed data; R.B.T., M.C.H., J.M.W., and W.J.P. interpreted results of experiments; R.B.T., J.M.W., and W.J.P. prepared figures; R.B.T. drafted manuscript; R.B.T. and W.J.P. edited and revised manuscript; R.B.T., M.C.H., J.S., J.M.W., and W.J.P. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adeoye OO, Bouthors V, Hubbell MC, Williams JM, Pearce WJ. VEGF receptors mediate hypoxic remodeling of adult ovine carotid arteries. J Appl Physiol (1985) 117: 777–787, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00012.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alioua A, Tanaka Y, Wallner M, Hofmann F, Ruth P, Meera P, Toro L. The large conductance, voltage-dependent, and calcium-sensitive K+ channel, Hslo, is a target of cGMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation in vivo. J Biol Chem 273: 32950–32956, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angeles DM, Williams J, Zhang L, Pearce WJ. Acute hypoxia modulates 5-HT receptor density and agonist affinity in fetal and adult ovine carotid arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H502–H510, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archer SL, Huang JM, Hampl V, Nelson DP, Shultz PJ, Weir EK. Nitric oxide and cGMP cause vasorelaxation by activation of a charybdotoxin-sensitive K channel by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 7583–7587, 1994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagwell CB, Hudson JL, Irvin GL III. Nonparametric flow cytometry analysis. J Histochem Cytochem 27: 293–296, 1979. doi: 10.1177/27.1.374589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brophy CM, Whitney EG, Lamb S, Beall A. Cellular mechanisms of cyclic nucleotide-induced vasorelaxation. J Vasc Surg 25: 390–397, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(97)70361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bullock BP, Habener JF. Phosphorylation of the cAMP response element binding protein CREB by cAMP-dependent protein kinase A and glycogen synthase kinase-3 alters DNA-binding affinity, conformation, and increases net charge. Biochemistry 37: 3795–3809, 1998. doi: 10.1021/bi970982t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Candia S, Garcia ML, Latorre R. Mode of action of iberiotoxin, a potent blocker of the large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Biophys J 63: 583–590, 1992. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81630-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casteels R, Wuytack F, Raeymaekers L, Himpens B. Ca2+-transport ATPases and Ca2+-compartments in smooth muscle cells. Z Kardiol 80, Suppl 7: 65–68, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers JJ, Nichols DE. A homology-based model of the human 5-HT2A receptor derived from an in silico activated G-protein coupled receptor. J Comput Aided Mol Des 16: 511–520, 2002. doi: 10.1023/A:1021275430021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charles SM, Zhang L, Cipolla MJ, Buchholz JN, Pearce WJ. Roles of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and myofilament Ca2+ sensitization in age-dependent cerebrovascular myogenic tone. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H1034–H1044, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00214.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durrant LM, Khorram O, Buchholz JN, Pearce WJ. Maternal food restriction modulates cerebrovascular structure and contractility in adult rat offspring: effects of metyrapone. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 306: R401–R410, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00436.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis SH, Corbin JD. Structure and function of cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. Annu Rev Physiol 56: 237–272, 1994. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furchgott RF. The pharmacological differentiation of adrenergic receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci 139: 553–570, 1967. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1967.tb41229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garay RP. [Cellular mechanisms of smooth muscle contraction]. Rev Mal Respir 17: 531–533, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerzanich V, Ivanov A, Ivanova S, Yang JB, Zhou H, Dong Y, Simard JM. Alternative splicing of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I in angiotensin-hypertension: novel mechanism for nitrate tolerance in vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res 93: 805–812, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000097872.69043.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giangiacomo KM, Garcia ML, McManus OB. Mechanism of iberiotoxin block of the large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel from bovine aortic smooth muscle. Biochemistry 31: 6719–6727, 1992. doi: 10.1021/bi00144a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gollasch M, Löhn M, Fürstenau M, Nelson MT, Luft FC, Haller H. Ca2+ channels, Ca2+ sparks, and regulation of arterial smooth muscle function. Z Kardiol 89, Suppl 2: 15–19, 2000. doi: 10.1007/s003920070095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanley NR, Hensler JG. Mechanisms of ligand-induced desensitization of the 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300: 468–477, 2002. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.2.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu XQ, Yang S, Pearce WJ, Longo LD, Zhang L. Effect of chronic hypoxia on alpha-1 adrenoceptor-mediated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling in ovine uterine artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 288: 977–983, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter CJ, Blood AB, White CR, Pearce WJ, Power GG. Role of nitric oxide in hypoxic cerebral vasodilatation in the ovine fetus. J Physiol 549: 625–633, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.038034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshi S, Nelson MT, Werner ME. Amplified NO/cGMP-mediated relaxation and ryanodine receptor-to-BKCa channel signalling in corpus cavernosum smooth muscle from phospholamban knockout mice. Br J Pharmacol 165: 455–466, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamitomo M, Longo LD, Gilbert RD. Right and left ventricular function in fetal sheep exposed to long-term high-altitude hypoxemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H399–H405, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khavandi K, Baylie RL, Sugden SA, Ahmed M, Csato V, Eaton P, Hill-Eubanks DC, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Greenstein AS. Pressure-induced oxidative activation of PKG enables vasoregulation by Ca2+ sparks and BK channels. Sci Signal 9: ra100, 2016. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyle BD, Hurst S, Swayze RD, Sheng J, Braun AP. Specific phosphorylation sites underlie the stimulation of a large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channel by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. FASEB J 27: 2027–2038, 2013. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-223669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leo MD, Bannister JP, Narayanan D, Nair A, Grubbs JE, Gabrick KS, Boop FA, Jaggar JH. Dynamic regulation of β1 subunit trafficking controls vascular contractility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 2361–2366, 2014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317527111. [Corrigendum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111 (May): 7879, 2014. doi:.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin MT, Hessinger DA, Pearce WJ, Longo LD. Developmental differences in Ca2+-activated K+ channel activity in ovine basilar artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H701–H709, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00138.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lincoln TM, Dey N, Sellak H. Invited review: cGMP-dependent protein kinase signaling mechanisms in smooth muscle: from the regulation of tone to gene expression. J Appl Physiol 91: 1421–1430, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lincoln TM, Wu X, Sellak H, Dey N, Choi CS. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype by cyclic GMP and cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase. Front Biosci 11: 356–367, 2006. doi: 10.2741/1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu HW, Hou PP, Guo XY, Zhao ZW, Hu B, Li X, Wang LY, Ding JP, Wang S. Structural basis for calcium and magnesium regulation of a large conductance calcium-activated potassium channel with β1 subunits. J Biol Chem 289: 16914–16923, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.557991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luttrell LM. Transmembrane signaling by G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Mol Biol 332: 3–49, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lymperopoulos A, Bathgate A. Arrestins in the cardiovascular system. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 118: 297–334, 2013. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394440-5.00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgado M, Cairrão E, Santos-Silva AJ, Verde I. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent relaxation pathways in vascular smooth muscle. Cell Mol Life Sci 69: 247–266, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0815-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura K, Koga Y, Sakai H, Homma K, Ikebe M. cGMP-dependent relaxation of smooth muscle is coupled with the change in the phosphorylation of myosin phosphatase. Circ Res 101: 712–722, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orstavik S, Natarajan V, Taskén K, Jahnsen T, Sandberg M. Characterization of the human gene encoding the type I alpha and type I beta cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PRKG1). Genomics 42: 311–318, 1997. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker RB, Waud DR. Pharmacological estimation of drug-receptor dissociation constants. Statistical evaluation. I. Agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 177: 1–12, 1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearce WJ. Mechanisms of hypoxic cerebral vasodilatation. Pharmacol Ther 65: 75–91, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00058-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearce WJ, Williams JM, Hamade MW, Chang MM, White CR. Chronic hypoxia modulates endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation through multiple independent mechanisms in ovine cranial arteries. Adv Exp Med Biol 578: 87–92, 2006. doi: 10.1007/0-387-29540-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pilz RB, Casteel DE. Regulation of gene expression by cyclic GMP. Circ Res 93: 1034–1046, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000103311.52853.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raman L, Georgieff MK, Rao R. The role of chronic hypoxia in the development of neurocognitive abnormalities in preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Dev Sci 9: 359–367, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroeder N, Mullmann TJ, Schmalhofer WA, Gao YD, Garcia ML, Giangiacomo KM. Glycine 30 in iberiotoxin is a critical determinant of its specificity for maxi-K versus KV channels. FEBS Lett 527: 298–302, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teng GQ, Nauli SM, Brayden JE, Pearce WJ. Maturation alters the contribution of potassium channels to resting and 5HT-induced tone in small cerebral arteries of the sheep. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 133: 81–91, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(01)00304-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teng GQ, Williams J, Zhang L, Purdy R, Pearce WJ. Effects of maturation, artery size, and chronic hypoxia on 5-HT receptor type in ovine cranial arteries. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275: R742–R753, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thorpe RB, Stockman SL, Williams JM, Lincoln TM, Pearce WJ. Hypoxic depression of PKG-mediated inhibition of serotonergic contraction in ovine carotid arteries. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R734–R743, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00212.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams JM, White CR, Chang MM, Injeti ER, Zhang L, Pearce WJ. Chronic hypoxic decreases in soluble guanylate cyclase protein and enzyme activity are age dependent in fetal and adult ovine carotid arteries. J Appl Physiol 100: 1857–1866, 2006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00662.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong JC, Bathina M, Fiscus RR. Cyclic GMP/protein kinase G type-Iα (PKG-Iα) signaling pathway promotes CREB phosphorylation and maintains higher c-IAP1, livin, survivin, and Mcl-1 expression and the inhibition of PKG-Iα kinase activity synergizes with cisplatin in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Cell Biochem 113: 3587–3598, 2012. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu Y, Eghbali M, Ou J, Lu R, Toro L, Stefani E. Quantitative determination of spatial protein-protein correlations in fluorescence confocal microscopy. Biophys J 98: 493–504, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu M, Sun CW, Maier KG, Harder DR, Roman RJ. Mechanism of cGMP contribution to the vasodilator response to NO in rat middle cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1724–H1731, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00699.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang T, Zhuang S, Casteel DE, Looney DJ, Boss GR, Pilz RB. A cysteine-rich LIM-only protein mediates regulation of smooth muscle-specific gene expression by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 282: 33367–33380, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou W, Dasgupta C, Negash S, Raj JU. Modulation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype in hypoxia: role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L1459–L1466, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00143.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou W, Negash S, Liu J, Raj JU. Modulation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype in hypoxia: role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase and myocardin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L780–L789, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90295.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou XB, Arntz C, Kamm S, Motejlek K, Sausbier U, Wang GX, Ruth P, Korth M. A molecular switch for specific stimulation of the BKCa channel by cGMP and cAMP kinase. J Biol Chem 276: 43239–43245, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zinchuk V, Wu Y, Grossenbacher-Zinchuk O, Stefani E. Quantifying spatial correlations of fluorescent markers using enhanced background reduction with protein proximity index and correlation coefficient estimations. Nat Protoc 6: 1554–1567, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]