Abstract

Airway remodeling, including increased airway smooth muscle (ASM) mass, is a hallmark feature of asthma and COPD. We previously identified the expression of bitter taste receptors (TAS2Rs) on human ASM cells and demonstrated that known TAS2R agonists could promote ASM relaxation and bronchodilation and inhibit mitogen-induced ASM growth. In this study, we explored cellular mechanisms mediating the antimitogenic effect of TAS2R agonists on human ASM cells. Pretreatment of ASM cells with TAS2R agonists chloroquine and quinine resulted in inhibition of cell survival, which was largely reversed by bafilomycin A1, an autophagy inhibitor. Transmission electron microscope studies demonstrated the presence of double-membrane autophagosomes and deformed mitochondria. In ASM cells, TAS2R agonists decreased mitochondrial membrane potential and increased mitochondrial ROS and mitochondrial fragmentation. Inhibiting dynamin-like protein 1 (DLP1) reversed TAS2R agonist-induced mitochondrial membrane potential change and attenuated mitochondrial fragmentation and cell death. Furthermore, the expression of mitochondrial protein BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (Bnip3) and mitochondrial localization of DLP1 were significantly upregulated by TAS2R agonists. More importantly, inhibiting Bnip3 mitochondrial localization by dominant-negative Bnip3 significantly attenuated cell death induced by TAS2R agonist. Collectively the TAS2R agonists chloroquine and quinine modulate mitochondrial structure and function, resulting in ASM cell death. Furthermore, Bnip3 plays a central role in TAS2R agonist-induced ASM functional changes via a mitochondrial pathway. These findings further establish the cellular mechanisms of antimitogenic effects of TAS2R agonists and identify a novel class of receptors and pathways that can be targeted to mitigate airway remodeling as well as bronchoconstriction in obstructive airway diseases.

Keywords: asthma, G protein-coupled receptor, TAS2R, mitochondria

airway inflammatory diseases such as asthma and COPD are characterized by inflammation, mucus production, airway remodeling, and hyperresponsiveness, resulting in severe bronchoconstriction (4, 32, 50). The chronic nature of these diseases leads to structural and functional changes in resident cells of the airway wall, including ASM cells (32, 33, 44, 45). Histological evaluation of asthmatic lung samples reveals a significant increase in the ASM mass (8, 21, 23, 29), which is correlated with asthma severity (2, 19, 60). Alterations in ASM mass and phenotype are now appreciated as pathogenic mechanisms of obstructive lung diseases (6).

G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling plays a vital role in the regulation of ASM contraction, relaxation, and proliferation (4, 10), and therefore, agonists/antagonists of GPCRs represent potentially efficacious anti-asthma medications. Current anti-asthma therapies, including β-agonists and corticosteroids, aim at alleviating bronchoconstriction and inflammation, respectively, but have a very limited effect on remodeling (4). Thus there is a pressing need for identifying new drugs that cause both ASM relaxation and inhibition of growth.

Recently, we identified the expression of type II taste receptors (TAS2Rs) on human ASM cells and characterized intracellular signaling mediated via these receptors using a panel of known TAS2R agonists (12, 55). Among the 25 known taste receptors are at least three subtypes that are highly expressed (T2R10, T2R14, and T2R31) and three more that are moderately expressed (T2R5, T2R4, and T2R19) in human ASM. Expression of TAS2Rs on guinea pig and murine ASM has also been demonstrated recently (39, 52). Extant TAS2R agonists include both synthetic and natural compounds. One group includes chloroquine and quinine, which activate T2R10, T2R14, and T2R31 expressed on human ASM cells (12, 40). Stimulation of ASM cells with TAS2R agonists resulted in an increase in intracellular calcium that was Gβγ, PLC, and IP3 dependent. Interestingly, elevation of calcium upon TASR stimulation was associated with a robust relaxation of ASM cells and airway rings. This relaxation effect of TAS2R agonists was confirmed by three independent laboratories using mouse, guinea pig, and human airways (12, 39, 52). Studies using lung slices (human and murine) and in vivo aerosol challenge in murine models have demonstrated efficacious bronchodilation by TAS2R agonists. These observations posit TAS2R agonists as a new class of bronchodilators for clinical use. A recent study from our laboratory demonstrated that TAS2R agonists such as chloroquine and quinine inhibit mitogen-induced human ASM growth (55). Furthermore, the antimitogenic effect of TAS2R agonist is mediated, at least partially, via inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway and arresting of cell cycle progression (55).

Increases in ASM mass could result from multiple mechanisms, including increases in cell number (hyperplasia), size (hypertrophy), and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) or a decrease in cell death. Inhibition of ASM growth by antimitogenic agents can occur via targeting of any of these mechanisms, including autophagy and mitochondrial-initiated cell death. In this study, we aimed to determine additional cellular mechanisms involved in the antimitogenic effect of TAS2R agonists chloroquine and quinine on human ASM cells. Using advanced microscopic imaging and biochemical tools herein, we demonstrate that TAS2R agonists modulate mitochondria dynamics and function, leading to ASM cell death. Chloroquine- and quinine-induced ASM cell death was reversed by pretreating cells with befilomycin A1, an autophagy inhibitor, suggesting the role of autophagy. Interestingly, the antimitogenic effect of TAS2R agonists on human ASM cells was attenuated by inhibiting Bnip3, a mitochondrial protein, using dominant-negative Bnip3 or a DLP1 inhibitor Mdivi-1, suggesting a central role for mitochondrial protein Bnip3 and autophagy in TAS2R agonist-mediated antimitogenic effect on human ASM.

METHODS

Materials.

Antibodies against Mfn1, Mfn2, and Bnip3 were from Abcam (Burlingame, CA). DLP1 and Opa1 antibodies were from BD Bioscience (Franklin Lakes, NJ). VDAC, beclin-1, and ATG-5 antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). IRDye 680 or 800 secondary antibodies were from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA). Quantitative PCR arrays and SYBR green reagents were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). The MTT cell proliferation assay kit, MitoTracker Green, and MitoSox red are from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). siRNA oligos were obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). Rabbit-anti LC3-β, anti-β-actin, bafilomycin A1 (Baf A1), 3-methyl adenine (3-MA), chloroquine, quinine, saccharine, and other reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or from previously identified sources (12, 55). Wild-type and dominant-negative Bnip3 adeno-associated virus were from ViGene Bioscience (Rockville, MD).

Cell culture.

Human ASM cultures were established from human tracheae or primary bronchi using the enzyme dissociation method and were grown in F-12 medium with supplements, as described previously (11, 12, 42). Cell cultures were either generated at Thomas Jefferson University or obtained from Dr. Reynold Panettieri’s laboratory (Rutgers University). Studies performed with these cells isolated from deidentified human lungs have been determined as not human subjects by the Institutional Review Board at Thomas Jefferson University. ASM cells in subculture during the second through fifth cell passages were used. The cells were maintained in F-12 medium with no serum and supplemented with 1% insulin transferrin selenium (arresting medium) for 24–48 h before the experiments.

Isolation of mitochondria.

Mitochondria were isolated from ASM cells after the treatments with TAS2R agonists using the Mitochondria Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) (25, 41). Briefly, 1 × 107 ASM cells were collected, washed with PBS, and resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer. Cell homogenates were prepared using a dounce homogenizer and incubated with 50 μl of anti-Tom22 coated beads for 1 h with gentle shaking at 4°C. After the nonspecific binding was washed out in the magnetic field, mitochondria were isolated for analysis.

siRNA transfection and viral (adeno-associated virus) infection.

siRNA transfection was performed in human ASM cells, as described previously (54). Briefly, cells were seeded in six-well plates 1 day before transfection. Transfection mixture was prepared by adding 2–5 μl of 5 μM siRNA and 5 μl of DharmaFECT1 (GE Healthcare) reagent to serum-free medium. After being incubated at room temperature for 20 min, the mixture was transferred to a new tube containing 1 ml of complete medium (final siRNA concentration was 25 nM) and transferred to cells after 5 min. Adeno-associated virus AAV infection was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ViGene Bioscience). Briefly, cells were seeded on a six-well plate 1 day before the infection. On the following day, cells were infected with 105/cell AAV particles expressing either wild-type or dominant-negative (DN) Bnip3. After a 12-h incubation, virus-containing media were replaced with regular culture media. The success in infection was monitored by green fluorescence protein (GFP) expression using a fluorescence microscope. For confocal studies, cells were cultured on confocal dishes, serum starved, and treated with TAS2R agonists for 24 h before propidium iodide (PI) staining was performed.

PI staining.

Human ASM cells were incubated with 4 μl of PI (10 mg/ml) in 1 ml of medium in a CO2 incubator. The staining solution was removed after 5 min, followed by three washes with PBS. ASM cell images were acquired using a confocal (λex 535 nm, λem 617 nm) microscope.

MTT and CyQuant assay.

MTT and CyQuant assays were performed as described previously (16, 55). Human ASM cells were grown to subconfluence in 96-well cell culture plates before being switched to growth arrest media for 24 h (F-12 + 1% ITS) and then treated with TAS2R agonists in the presence or absence of PDGF (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. In some cases, cells were pretreated with 20 nM Baf A1 or 5 μM 3-MA for 15 min or 3 μM Mdivi-1 for 2 h before being treated with TAS2R agonists ± PDGF. In pilot studies, we treated cells with different concentrations of Baf A1, 3-MA, and Mdivi-1 and established the optimum concentration that inhibited autophagy without affecting viability in human ASM cells for all the studies. These inhibitors have been well characterized in previous studies on ASM cells (16–18). At the end of the treatment, media were removed and cells incubated with MTT or CyQuant reagent for 4 or 1 h, respectively, and absorbance or fluorescence was determined using a plate reader.

Immunostaining and light microscope imaging.

Cells were plated onto precleared glass coverslips in six-well culture dishes and fixed for 15 min at 4°C in 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and then permeabilized by incubation for 5 min at 4°C using 3% PFA and 0.3% Triton X-100. Fixed cells were first blocked for 2 h at room temperature in cyto-TBS buffer containing 1% BSA and 2% normal donkey serum. Incubation with primary antibody rabbit anti-LC3βII (1:100) occurred overnight at 4°C in cyto-TBST, followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. For negative controls, cells were incubated with either isotype-matched mouse IgG or rabbit antiserum. Coverslips were mounted using ProLong antifade medium (Molecular Probes). Fluorescent imaging of LC3 was performed by capturing a mid-cell section of 0.3-μm focal depth using an Olympus LX-70 FluoView Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (Olympus America, Melville, NY) equipped with a ×40 objective. Bright-field images were acquired to assess the morphology of the cell with treatment protocol.

Electron microscopy studies.

The ultrastructural details of the cell were assessed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to measure autophagosome formation and assess mitochondrial integrity (51). Cells were grown in six-well culture plates, treated as described above, and processed further for TEM. Imaging was performed at the core facility at the University of Maryland (Baltimore, MD) using a FEI Tecnai T12 high-resolution microscope.

Western blotting.

Western blotting (immunoblotting) was performed as described previously (47, 48). The images were acquired by Odessey image scanner (Li-Cor). Equal loading of protein was ensured by determining the expression of β-actin or tubulin.

RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and real-time PCR array.

Cells grown on six-well plates were treated with PDGF or vehicle with or without pretreatment with TAS2R agonists for 24 h, and total RNA was harvested as described in our previous studies (42, 55). Total RNA (1 μg) was converted to cDNA by RT reaction and the reaction stopped by heating the samples at 94°C for 5 min. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the RT2 Profiler PCR Array for mitochondria genes (PAHS-087Z), using an Applied Biosystems real-time PCR machine (Mx3005). Raw CT values were obtained using the software-recommended threshold fluorescence intensity. Gene expression data was calculated as described previously using expression of internal control gene (GAPDH) (12, 54).

Assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species generation.

Mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurements were performed as described previously (48). Briefly, after the treatment with TAS2R agonists, ASM cells were incubated with mitochondrial membrane potential dye tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) or mitochondrial ROS probe MitoSox red for 30 min and then washed with PBS to remove the unincorporated dyes. Mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS generation were monitored by live-cell imaging using a confocal microscope. Mitochondria images were acquired by Fluoview (Olympus) using a ×60 oil objective and analyzed using National Institutes of Health (NIH) ImageJ 1.44 software.

Statistical analyses.

Data are presented as means ± SE from at least three experiments, in which each experiment was performed using a different ASM culture derived from a unique donor; n represents the number of primary cell cultures used in the experiments obtained from different donors unless otherwise mentioned. Individual data points from a single experiment were calculated as the mean value from three replicate observations and reported as fold change from the vehicle-treated group. Statistically significant differences among groups were assessed by either Student’s t-test or ANOVA using Prism Graphpad Software 6.0 (Graphpad, La Jolla, CA), with values of P < 0.05 sufficient to reject the null hypothesis.

RESULTS

TAS2R agonists induce ASM cell death.

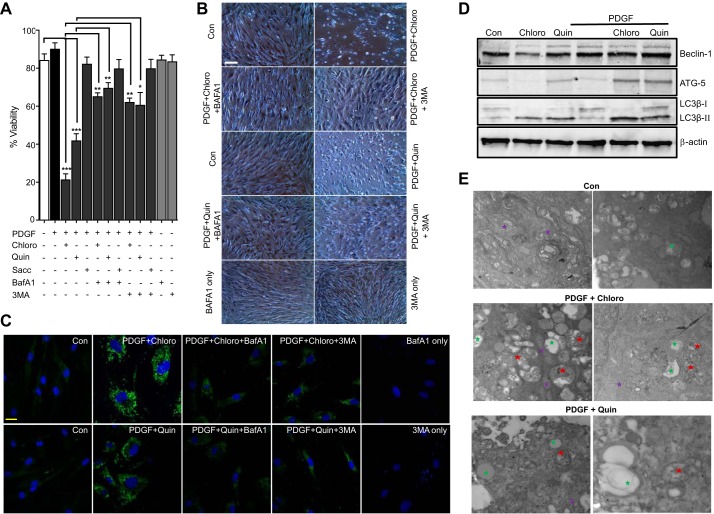

We used platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) to induce ASM growth and determined the effect of three different TAS2R agonists, chloroquine (chloro), quinine (quin), and saccharin (Sacc), on mitogen-induced ASM growth. ASM cell survival was significantly decreased by chloroquine and quinine (Fig. 1A), supporting the antimitogenic effect of TAS2R agonists on human ASM cells (55). Saccharine, a relatively weak TAS2R agonist, caused a modest inhibition of ASM growth that was not statistically different from vehicle-pretreated control. Furthermore, human ASM cells were pretreated with the autophagy inhibitor Baf A1, followed by TAS2R agonists. Baf A1 mitigated the cell death-inducing effect of chloroquine and quinine on human ASM cells (Fig. 1, A and B), suggesting a potential role of autophagy. Induction of autophagy in human ASM by Chloro and Quin was further confirmed by immunofluorescence and immunoblot detection of LC3β puncta formation and LC3β ΙΙ accumulation, respectively. LC3β accumulation in human ASM cells was significantly reduced in the presence of Baf A1 and 3-methyl adenine (3-MA) (Fig. 1, C and D). Transmission electron microscopy revealed accumulation of double-membrane autophagosomes, vesicles, and deformed mitochondria in human ASM cells upon treatment with the TAS2R agonists Chloro and Quin in the presence of PDGF (Fig. 1E). Collectively, these findings suggest the involvement of autophagy in TAS2R agonist-mediated antimitogenic effect on human ASM cells.

Fig. 1.

TAS2R agonists induce human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell death. Human ASM cells were serum starved for 24 h and then treated with either vehicle or TAS2R agonists [chloroquine (chloro), quinine (quin), and saccharin (sacc)] at 125 μM in the presence of PDGF (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. A: a select set of cells were pretreated with the autophagy inhibitors baflomycin A (Baf A1; 20 nM) and 3-methyladenine (3-MA; 5mM). Cell viability was measured by MTT assay (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001; n = 5). B: light scope images showing cells treated with vehicle control (Con), chloro, quin, and chloro or quin + PDGF and cells pretreated with Baf A1 or 3-MA before the treatment with PDGF or chloro or quin (n = 4). C: a select set of cells were pretreated with either Baf A1 or 3-MA before the treatment with PDGF + chloro or quin. Cells were stained with anti-LC3 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100) followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Scale bars, 20 μm. Representative confocal images are presented (n = 4). D: immunoblotting showing results obtained after cells were treated with either chloro or quin or PDGF alone or chloro or quin + PDGF. Key autophagy marker proteins beclin-1, ATG-5, and LC3β II were found to be increased by treatment with TAS2R agonist in the presence of PDGF; results shown are representative of 5 independent experiments using 5 human primary ASM cells (n = 5). E: transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (×6,500 magnification) showing subcellular structural changes in ASM. Green, vesicles; red, autophagosome; purple, mitochondria. Note accumulation of empty vesicles, double-membrane autophagosomes, and deformed mitochondria in cells treated with TAS2R agonist in the presence of PDGF. Images shown are representative of n = 3 different experiments using primary human ASM cultures obtained from 3 different donors.

TAS2R agonists impair mitochondrial function in human ASM cells.

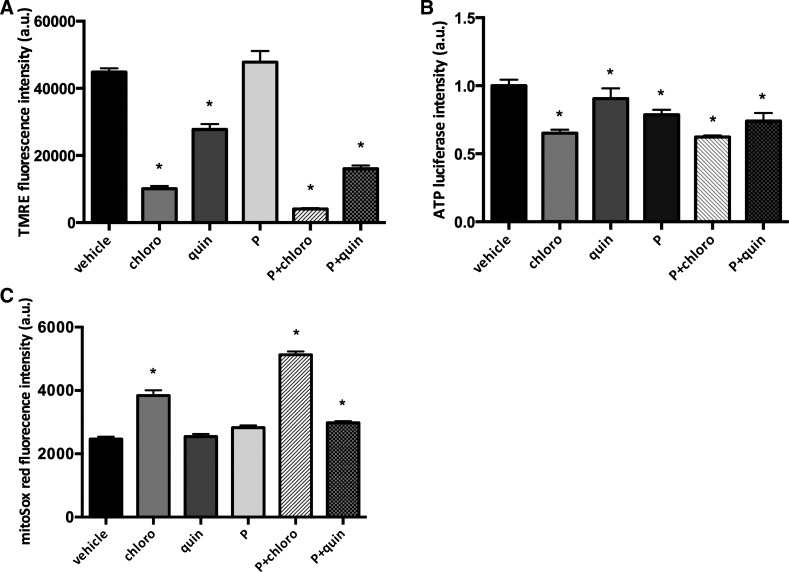

Our TEM studies demonstrated that treatment of human ASM cells with TAS2R agonists for 24 h increased accumulation of deformed mitochondria (Fig. 1E). Therefore, we next assessed whether mitochondrial function was altered by TAS2R agonists. Indeed, the mitochondrial membrane potential was significantly decreased after exposure to TAS2R agonists compared with vehicle-treated cells (4,078.89 ± 255.77, chloro + PDGF; 16,389.80 ± 973.86, quin + PDGF; and 44,871.11 ± 1,159.62, vehicle controls; P < 0.05, n = 9; Fig. 2A). Because mitochondrial membrane potential is the primary driver for ATP synthesis (13, 28), we further examined cellular ATP levels in ASM cells exposed to chloroquine and quinine. TAS2R agonists significantly decreased cellular ATP levels compared with vehicle-treated controls (0.62 ± 0.03-fold basal for chloro + PDGF; 0.74 ± 0.14-fold basal for quin + PDGF; P < 0.05, n = 3; Fig. 2B). Furthermore, mitochondrial ROS levels in human ASM cells were significantly increased by TAS2R agonists (5,128.66 ± 104.51, chloro + PDGF; 2,982.24 ± 254.28, quin + PDGF; and 2,467.8 ± 356.44, vehicle-treated controls; n = 24, P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). Collectively, these data strongly suggest that chronic exposure of human ASM cells to TAS2R agonists chloroquine and quinine results in mitochondrial dysfunction, as indicated by a significant decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and cellular ATP levels and a significant increase in mitochondrial ROS.

Fig. 2.

TAS2R agonists impair mitochondrial function and decrease cellular ATP levels. Human ASM cells were serum starved for 24 h and then treated with either vehicle or 125 μM TAS2R agonists (chloro and quin) in the absence and presence of 10 ng/ml PDGF (P) for 24 h. A: mitochondrial membrane potential was measured using tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE; *P < 0.05, n = 9; 3 measurements in each of 3 different cell cultures). B: cellular ATP levels were measured as luciferase intensity (*P < 0.05, n = 3). C: mitochondrial ROS was measured by confocal live-cell imaging using MitoSox Red (*P < 0.05, n = 24; 4 different ASM cell cultures and 6 measurements in each culture).

TAS2R agonists increase mitochondrial fragmentation in human ASM cells.

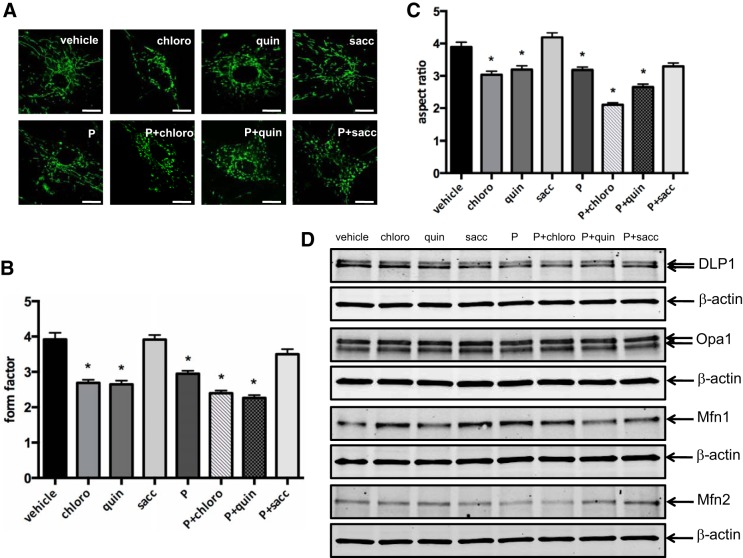

To further understand the subcellular effect of TAS2R agonists in human ASM cells, we determined the effect of chloroquine and quinine on mitochondrial dynamics. In control cells exposed to vehicle, mitochondria were interconnected and formed tubular and granular network. Exposure of cells to TAS2R agonists caused an increase in fragmented mitochondria, as determined by live-cell confocal imaging (Fig. 3A). The mitochondrial morphology data were further analyzed quantitatively using form factor (an indicator of mitochondria branching) and aspect ratio (an indicator of mitochondria length). Chloroquine and quinine significantly increased mitochondrial fragmentation (Fig. 3, A–C). The mitochondrial branches were significantly decreased by the exposure of ASM cells to chloroquine plus PDGF (2.40 ± 0.08; n = 5, P < 0.05) or quinine plus PDGF (2.26 ± 0.08; n = 5, P < 0.05) compared with vehicle control (3.92 ± 0.19) (Fig. 3B). Similarly, compared with vehicle control (3.89 ± 0.15), chloroquine or quinine plus PDGF significantly decreased length of mitochondria (2.1 ± 0.06 and 2.65 ± 0.09, respectively; n = 5, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, exposure of human ASM cells to TAS2R agonists did not significantly change expression levels of mitochondrial dynamics proteins, including dynamin-like protein 1 (DLP1), optic atrophy 1 (Opa1), mitofusin 1 (Mfn1), and mitofusin 2 (Mfn2), indicating that the alteration in mitochondrial dynamics is not due to the changes in the expression levels of the mitochondrial dynamic proteins (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that chronic exposure of human ASM cells to chloroquine and quinine alters mitochondrial dynamics, leading to mitochondrial fragmentation.

Fig. 3.

TAS2R agonists increase fragmented mitochondria. Human ASM cells were serum starved for 24 h and then treated with either vehicle or TAS2R agonists (chloro, quin, and sacc) at 125 μM in the absence and presence of 10 ng/ml PDGF (P) for 24 h. A: mitochondria morphology was monitored by confocal live-cell imaging using MitoTracker green. Shown are representative images obtained from n = 5 different ASM cell cultures. Scale bar, 40 μm. B and C: quantitative measurement of mitochondrial morphology using form factor (B) and aspect ratio (C) after TAS2R agonist treatment (*P < 0.05; n = 5). D: mitochondrial fission protein dynamin-like protein (DLP1) and mitochondrial fusion protein optic atrophy 1 (Opa1), mitofusin 1 (Mfn1), and mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) levels were measured by Western blot. Representative blots for DLP1, Opa1, Mfn1, and Mfn2 were obtained from n = 3 different ASM cultures. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

TAS2R agonists increase Bnip3 expression and DLP1 mitochondrial localization in human ASM cells.

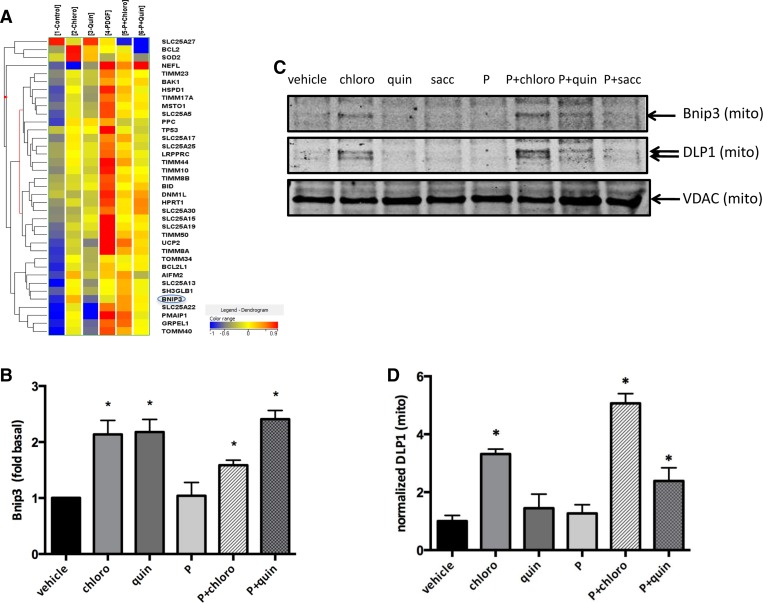

To determine the molecular mechanisms by which chloroquine and quinine change mitochondrial dynamics and function, we performed RT2 profiler PCR Array analysis (Fig. 4). Real-time PCR analysis revealed significant upregulation of Bnip3 expression in human ASM cells exposed to chloroquine and quinine (1.59 ± 0.05- and 2.41 ± 0.07-fold control, chloro and quin+PDGF, respectively; P < 0.05, n = 4; Fig. 4, A and B).

Fig. 4.

TAS2R agonists increase BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (Bnip3) gene expression and DLP1 mitochondrial localization. Human ASM cells were serum starved for 24 h and then treated with either vehicle or 125 μM TAS2R agonists (chloro and quin) in the absence and presence of 10 ng/ml PDGF (P) for 24 h. A: RT2 profiler PCR array showing mitochondrial gene expression profile (n = 4). B: Bnip3 expression levels after TAS2R agonist treatment (*P < 0.05; n = 4). C: mitochondrial DLP1 and Bnip3 protein levels assayed by Western blot using isolated mitochondrial protein lysates. Voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) was used as internal control for mitochondrial proteins. D: quantified data from C showing mitochondrial DLP1 protein levels normalized to VDAC (*P < 0.05; n = 3).

To explore the molecular mechanisms by which chloroquine and quinine alter mitochondria morphology and function, we isolated mitochondria from human ASM cells exposed to TAS2R agonists. Western blotting of lysates from isolated mitochondria demonstrated significantly increased levels of DLP1 in the mitochondrial fraction upon treatment with chloroquine or quinine plus PDGF compared with vehicle controls (Fig. 4, C and D). There was no significant change in the protein levels of other mitochondrial proteins, such as voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC; Fig. 4C, bottom). Other studies have demonstrated that Bnip3 increases DLP1 in mitochondria (34). Our data support a model in which TAS2R agonists upregulate Bnip3 expression, which increases DLP1 levels in mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction.

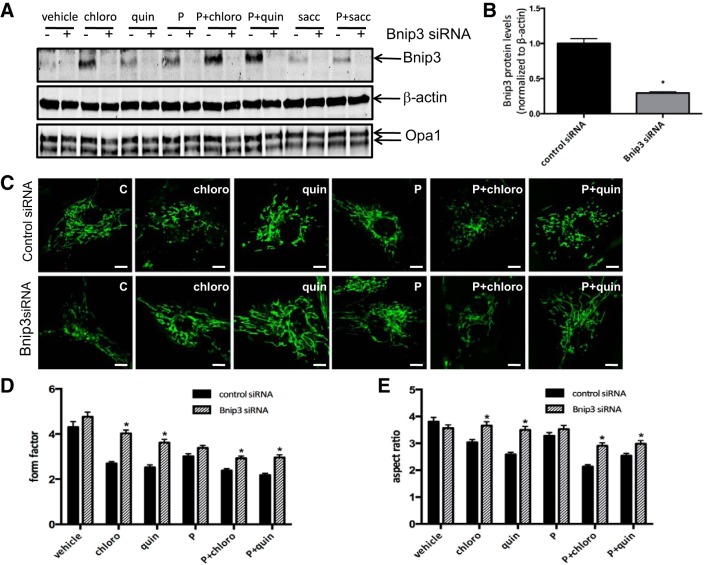

Bnip3 siRNA partly reverses TAS2R agonist-induced mitochondrial fragmentation.

To confirm the role of Bnip3 in TAS2R-induced mitochondrial fragmentation, we downregulated Bnip3 in human ASM cells, using a siRNA approach. Transfection of human ASM cells with Bnip3 siRNA significantly decreased Bnip3 levels without affecting other mitochondrial proteins, such as Opa1 (Fig. 5, A and B). More importantly, transfection with Bnip3 siRNA partly reversed mitochondrial fragmentation induced by chloroquine or quinine plus PDGF, as indicated by confocal imaging as well as the analysis of form factor and aspect ratio (Fig. 5, C–E). In Bnip3 siRNA-transfected human ASM cells, mitochondrial branches and length were significantly increased compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 5, C–E). Downregulation of Bnip3 expression by siRNA did not have significant effects on the protein levels of DLP1 (data not shown). These data strongly suggest that Bnip3 plays a role in TAS2R agonist-induced mitochondrial fragmentation. However, current siRNA/shRNA approaches (that work in primary ASM) are not amenable to analyses of ASM growth, and we were not able to demonstrate the role of Bnip3 in the regulation of ASM growth by TAS2R agonists. Therefore, we used additional approaches to downregulate mitochondrial Bnip3 levels.

Fig. 5.

Bnip3 siRNA partly reverses TAS2R agonist-induced mitochondrial fragmentation. Human ASM cells were transfected with Bnip3 siRNA and then treated with either vehicle or 125 μM TAS2R agonists (chloro, quin, and sacc) in the absence and presence of 10 ng/ml PDGF (P) for 24 h. A and B: Bnip3 siRNA significantly decreased Bnip3 protein levels (*P < 0.05; n = 3). β-Actin was used as loading control. C: representative confocal images of MitoTracker-labeled mitochondria. Scale bar, 50 μm. D and E: quantitative analysis of mitochondria images using form factor (D) and aspect ratio (E). *P < 0.05; n = 4.

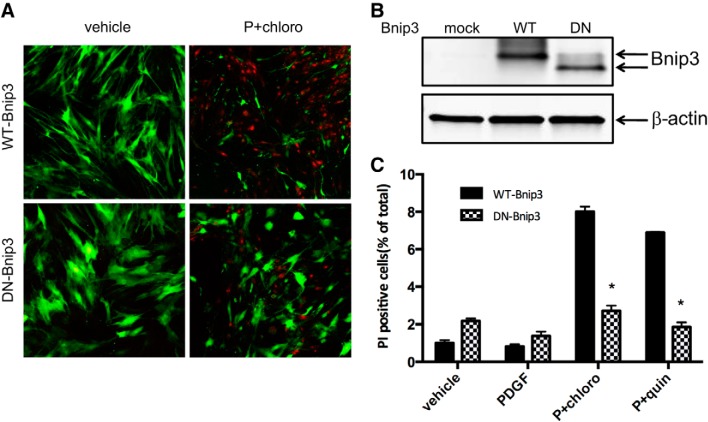

Dominant-negative Bnip3 inhibits TAS2R agonist-induced cell death in human ASM cells.

We have demonstrated that TAS2R agonist-induced increase in mitochondrial fragmentation and cell death in human ASM cells is associated with increased Bnip3 expression. To further understand the role of Bnip3 in TAS2R agonist-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and cell death in ASM cells, we generated adeno-associated virus (AAV) expressing wild-type (WT) or dominant-negative (DN) Bnip3 lacking the COOH-terminal mitochondrial localization domain. The truncated Bnip3 does not localize to mitochondria and functions as the dominant-negative form of Bnip3. The infection efficiency was determined by GFP fluorescence (Fig. 6A). The expression of WT and DN Bnip3 was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 6B). Using this approach, we determined the role of Bnip3 in TAS2R agonist-induced cell death in Bnip3-expressing human ASM cells (Fig. 6C). TAS2R agonist-induced cell death was significantly decreased in human ASM cells transfected with DN-Bnip3 compared with cells transfected with WT-Bnip3 (a 66% decrease in the chloro + PDGF group and a 73% decrease in quin + PDGF group; n = 4, P < 0.01 for both). These findings demonstrate that TAS2R agonist-induced ASM cell death is mediated via Bnip3 localization to mitochondria and mitochondrial mechanisms.

Fig. 6.

Dominant-negative Bnip3 inhibits TAS2R agonist-induced human ASM cell death. Wild-type and dominant-negative Bnip3 were transiently expressed in human ASM cells. After serum starvation for 24 h, cells were treated with vehicle, PDGF, or 125 μM TAS2R agonists (chloro or quin) in the presence of 10 ng/ml PDGF (P) for 24 h. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)- and propidium iodide (PI)-positive cells were recorded by confocal imaging. A: representative confocal images indicating the live (GFP positive; green) as well as dead (PI positive; red) cells. B: representative Western blot confirming the successful expression of wild-type Bnip3 (WT) and dominant-negative (DN) Bnip3 in human ASM cells. C: human ASM cell survival assay measured by PI staining. These studies were performed using 3–4 different ASM cell cultures obtained from different donors. *P < 0.05.

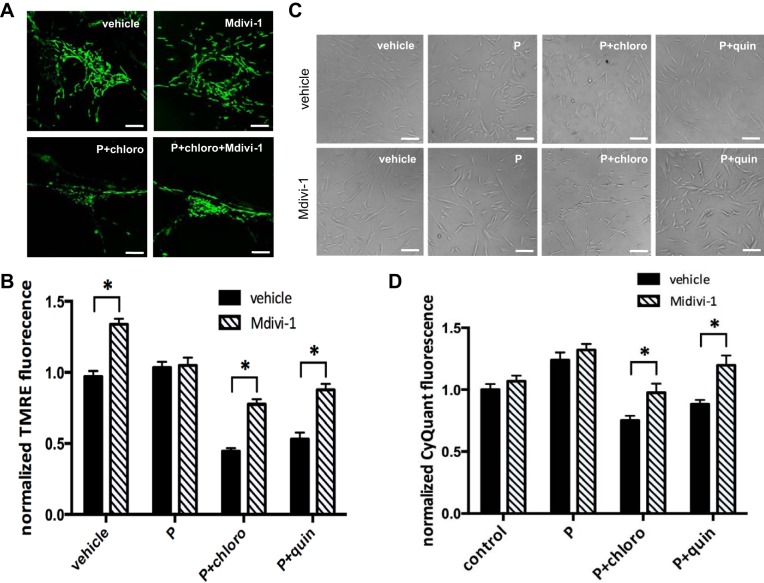

Inhibition of mitochondrial fission by DLP1 inhibitor Mdivi-1 attenuates TAS2R agonist-induced mitochondrial fragmentation, decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, and cell death in human ASM cells.

Our data suggest that chronic exposure of human ASM cells to TAS2R agonists increases mitochondrial fragmentation. Because excessive mitochondrial fission causes mitochondrial depolarization and cell death (27, 63), we hypothesized that inhibition of mitochondrial fission using the DLP1 inhibitor Mdivi-1 would rescue loss of mitochondrial functions and cell death induced by TAS2R agonists. Preincubation of ASM cells with 3 μM Mdivi-1 for 2 h, a well-established inhibitor of DLP1, decreased chloroquine- and quinine-induced mitochondrial fragmentation (Fig. 7A). Mdivi-1 pretreatment significantly reversed the decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential induced by TAS2R agonists (69% increase vs. chloro + PDGF and 62.1% increase vs. quin + PDGF; n = 10, P < 0.05 for both; Fig. 7B). Furthermore, pretreatment with Mdivi-1 significantly decreased TAS2R agonist-induced cell death (30% increase in cell survival vs. chloro + PDGF and 35.4% increase vs. quin + PDGF; n = 3, P < 0.05 for both; Fig. 7, C and D). These data suggest that TAS2R agonists increase mitochondrial DLP1 accumulation, leading to mitochondrial fragmentation and cell death.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of mitochondrial fission by Mdivi-1 increased mitochondrial membrane potential and decreased TAS2R agonist-induced cell death. Human ASM cells were serum starved for 24 h and preincubated with either vehicle or 3 μM Mdivi-1 for 2 h. Following the incubation of vehicle or Mdivi-1, cells were treated with vehicle, PDGF, or 125 μM TAS2R agonists (chloro or quin) in the presence of 10 ng/ml PDGF (P) for 24 h. A: confocal live-cell imaging showing mitochondria labeled with MitoTracker Green. B: mitochondrial membrane potential as measured by TMRE fluorescence (*P < 0.05, n = 10; 5 different ASM cultures with 2 measurements in each cell culture). C: representative light scope images of human ASM cells 24 h after treatment. D: human ASM cell viability measured by CyQuant fluorescence (*P < 0.05; n = 3).

DISCUSSION

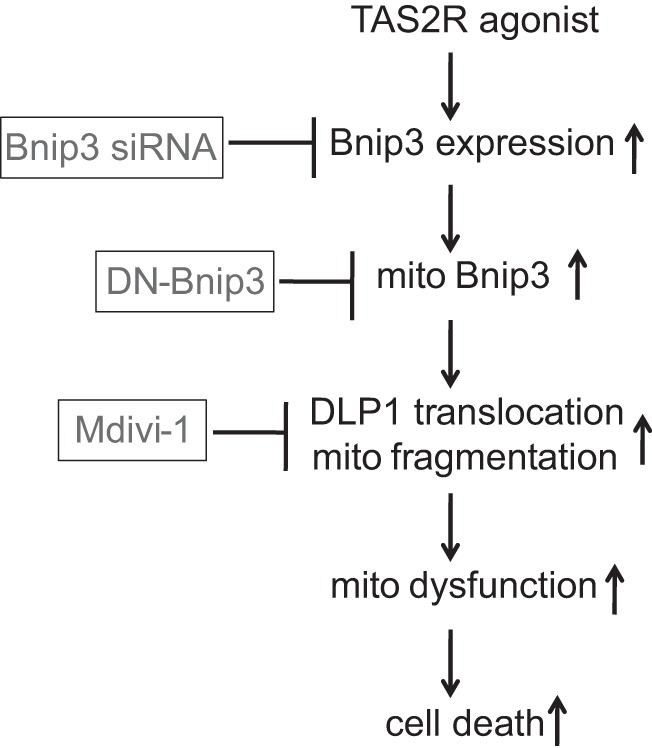

In this study, we established that chronic exposure of human ASM cells to the TAS2R agonists chloroquine and quinine inhibits human ASM cell survival via Bnip3 upregulation, DLP-1-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation, and mitochondrial dysfunction (as indicated by decreased mitochondrial membrane potential and cellular ATP levels and increased mitochondrial ROS), leading to initiation of autophagy. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission attenuated the decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and decreased TAS2R agonist-induced ASM cell death. Furthermore, inhibition of Bnip3 mitochondrial localization by expressing dominant-negative Bnip3 increased human ASM cell survival upon exposure of TAS2R agonists. Our data support a model in which TAS2R agonists inhibit ASM cell survival via Bnip3-mediated mitochondria-dependent mechanism of initiating autophagy (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Proposed mechanisms by which TAS2R agonists induce ASM cell death. TAS2R agonists cause upregulation of Bnip3 expression, followed by increased DLP1 mitochondrial localization, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell death, which can be attenuated by Mdivi-1 and dominant-negative Bnip3 (DN-Bnip3).

Autophagy causes proteolytic degradation of cytosolic components. There are three types of autophagy: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy. All three of these processes degrade cytosolic components at the lysosomes (43). This is mediated by a special organelle called autophagosome. Autophagic process consists of several sequential steps, including sequestration, degradation, and amino acid generation. We used two autophagy inhibitors (Baf-A1 and 3-MA) that work by stopping autophagy flux inside cells. 3-MA inhibits autophagy by blocking autophagosome formation via the inhibition of type III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K), whereas Baf-A1, a lysosomal proton pump inhibitor, inhibits lysosomal ATP and blocks the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes (15, 30). Autophagy is active in most of the cells in the body at the basal level to remove damaged organelles and proteins. However, autophagy can also be stimulated in stress situations such as nutrient depletion. During nutrient shortage, autophagy provides the constituents required for survival. Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved process to maintain the energy balance (35, 37, 49). Recent studies have demonstrated that autophagy plays a role in a variety of physiological and pathological processes besides adaptation to starvation such as development, aging, cancer, and muscle disorder (43). Autophagic removal of damaged proteins and organelles, including mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and peroxisomes, serves as an important quality control mechanism for cell survival (20). The regulation of autophagy in mammals is very complicated and involves multiple signaling pathways (5, 7, 46). Dysregulation of autophagy is linked to cell death (9, 38). For example, accumulation of ATGs has been found in mammalian cells undergoing autophagic cell death, which requires the presence of Bcl-2 family proteins (56). Furthermore, excessive autophagy in cells has been shown to induce cell death (9, 38). Our findings in this study demonstrate that chloroquine- and quinine-mediated cell death in human ASM cells involves autophagy.

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that undergo fission and fusion constantly. Mitochondrial fission and fusion are the key determinants of mitochondria morphology and function (24). Through fission and fusion mechanisms, mitochondria change their length and number. In addition, fission and fusion allow mitochondria to exchange lipid membranes and intramitochondrial substance. Such an exchange is essential for maintaining healthy mitochondria population. The shape of the mitochondria is important for the distribution of mitochondria, especially in highly polarized cells such as neurons. Excessive mitochondria fission facilitates cell death and the release of intermembrane space substances (36, 61, 62). Mitochondria become elongated when fusion is dominant or fission is insufficient. In contrast, enhanced fission or insufficient fusion causes fragmented mitochondria.Well-balanced fission and fusion are essential for mitochondria health and function. Altered mitochondrial dynamics is found in human diseases and aging (1, 3, 24, 36, 58, 61, 62). Treatment of human ASM cells with chloroquine and quinine resulted in an increased mitochondrial fission, leading to accumulation of fragmented mitochondria and loss of mitochondrial functions.

Mitochondrial fission and fusion are tightly controlled by mitochondrial dynamic machineries. Opa1, Mfn1, and Mfn2 are the key mitochondrial fusion machineries (3, 36). DLP1 is indispensable for mitochondrial fission. DLP1 deletion causes an increase in elongated mitochondria. In contrast, increased mitochondrial DLP1 levels lead to mitochondrial fragmentation (26, 57). Our data support a key role for DLP1 in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in response to TAS2R agonist treatment. Increased mitochondrial fragmentation in cells exposed to TAS2R agonists indicates a shift in the balance between fission and fusion that is likely due to enhanced mitochondrial localization of DLP1. The key role of DLP1-mediated mitochondrial fission in TAS2R agonist-induced cell death was further demonstrated by experiments using DLP1 inhibitor Mdivi-1. Mdivi-1 inhibited TAS2R agonist-induced mitochondrial fission, reversed mitochondrial membrane potential, and attenuated ASM cell death.

In this study, we also demonstrated that TAS2R agonists upregulate expression of Bnip3 and regulate DLP1 translocation to mitochondria. Our data are consistent with recent studies showing that Bnip3 causes DLP1 mitochondrial localization and mitochondrial fragmentation (34). Bnip3 was originally identified as a BH3-only proapoptotic protein of Bcl-2 family inducing mitophagy and mitochondria-mediated cell death. It localizes to the mitochondrial outer membrane and induces mitochondria-initiated cell death through modulation of outer mitochondria membrane permeabilization (31, 53). The expression of Bnip3 is inducible. For example, in cardiac tissues, Bnip3 expression is increased by hypoxia, and upregulation of Bnip3 is responsible for ischemia injury-induced cardiomyocyte death (14). Consistent with these findings, our data suggest a role for Bnip3 in TAS2R agonist-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and cell death. Although hypoxia-induced autophagy involves Bnip3, its role in the regulation of cardiomyocyte death is controversial. In an ischemia-reperfusion model, Bnip3-induced autophagy protected myocytes from cell death (22). However, another study showed that Bnip3 promoted autophagic cell death (59). Interestingly, in our study, knocking down Bnip3 partly reversed mitochondrial fragmentation but did not reverse TAS2R agonist-induced ASM cell death (data not shown). This presumably is because cell growth assay requires treatment over 72 h, by which time the inhibitory effect of siRNA on Bnip3 expression was diminished. Alternatively, dominant-negative Bnip3, which inhibits Bnip3 mitochondrial localization, significantly reversed TAS2R agonist-induced ASM cell death. Our data suggest that in response to TAS2R agonists, increased mitochondrial Bnip3 recruits more DLP1 to mitochondria, leading to mitochondrial fragmentation and ASM cell death.

Our previous study demonstrated that the TAS2R agonists chloroquine and quinine inhibit ASM proliferation induced by FBS, PDGF, or EGF. The antimitogenic effects are mediated largely by TAS2R agonist inhibition of cell cycle progression (55). The findings from the current studies demonstrate the role of mitochondria-dependent mechanisms in inhibiting ASM growth by TAS2R agonists. Our data suggest that Bnip3 is a mitochondrial target for the antimitogenic effect of TAS2R agonist. Additional studies are needed to determine the relative contribution of multiple cellular mechanisms in mediating the antimitogenic effect of TAS2R agonists on human ASM cells. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the beneficial effect of TAS2R agonists in mitigating ASM growth, a key component of airway remodeling in asthma pathogenesis, further underscoring the potential for exploring TAS2Rs as anti-asthma therapeutic targets.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grant from the American Asthma Foundation and National Institutes of Health Grant AG-041265 (to D. A. Deshpande).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.P., P.S., and S.D.S. performed experiments; S.P., P.S., and D.A.D. analyzed data; S.P., P.S., and D.A.D. interpreted results of experiments; S.P., P.S., and D.A.D. prepared figures; S.P., P.S., and D.A.D. drafted manuscript; S.P., P.S., S.D.S., and D.A.D. approved final version of manuscript; P.S. and D.A.D. conceived and designed research; P.S. and D.A.D. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of P. Sharma: Woolcock Institute of Medical Research and School of Life Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bach D, Pich S, Soriano FX, Vega N, Baumgartner B, Oriola J, Daugaard JR, Lloberas J, Camps M, Zierath JR, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Wallberg-Henriksson H, Laville M, Palacín M, Vidal H, Rivera F, Brand M, Zorzano A. Mitofusin-2 determines mitochondrial network architecture and mitochondrial metabolism. A novel regulatory mechanism altered in obesity. J Biol Chem 278: 17190–17197, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benayoun L, Druilhe A, Dombret MC, Aubier M, Pretolani M. Airway structural alterations selectively associated with severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167: 1360–1368, 2003. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200209-1030OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bereiter-Hahn J. Mitochondrial dynamics in aging and disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 127: 93–131, 2014. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394625-6.00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billington CK, Penn RB. Signaling and regulation of G protein-coupled receptors in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res 4: 2, 2003. doi: 10.1186/rr195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byfield MP, Murray JT, Backer JM. hVps34 is a nutrient-regulated lipid kinase required for activation of p70 S6 kinase. J Biol Chem 280: 33076–33082, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camoretti-Mercado B. Targeting the airway smooth muscle for asthma treatment. Transl Res 154: 165–174, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Codogno P, Meijer AJ. Autophagy and signaling: their role in cell survival and cell death. Cell Death Differ 12, Suppl 2: 1509–1518, 2005. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dekkers BG, Maarsingh H, Meurs H, Gosens R. Airway structural components drive airway smooth muscle remodeling in asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc 6: 683–692, 2009. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-056DP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denton D, Nicolson S, Kumar S. Cell death by autophagy: facts and apparent artefacts. Cell Death Differ 19: 87–95, 2012. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshpande DA, Penn RB. Targeting G protein-coupled receptor signaling in asthma. Cell Signal 18: 2105–2120, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deshpande DA, Theriot BS, Penn RB, Walker JK. β-Arrestins specifically constrain β2-adrenergic receptor signaling and function in airway smooth muscle. FASEB J 22: 2134–2141, 2008. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-102459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshpande DA, Wang WC, McIlmoyle EL, Robinett KS, Schillinger RM, An SS, Sham JS, Liggett SB. Bitter taste receptors on airway smooth muscle bronchodilate by localized calcium signaling and reverse obstruction. Nat Med 16: 1299–1304, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nm.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimroth P, Kaim G, Matthey U. Crucial role of the membrane potential for ATP synthesis by F(1)F(o) ATP synthases. J Exp Biol 203: 51–59, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diwan A, Krenz M, Syed FM, Wansapura J, Ren X, Koesters AG, Li H, Kirshenbaum LA, Hahn HS, Robbins J, Jones WK, Dorn GW II. Inhibition of ischemic cardiomyocyte apoptosis through targeted ablation of Bnip3 restrains postinfarction remodeling in mice. J Clin Invest 117: 2825–2833, 2007. doi: 10.1172/JCI32490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghavami S, Eshragi M, Ande SR, Chazin WJ, Klonisch T, Halayko AJ, McNeill KD, Hashemi M, Kerkhoff C, Los M. S100A8/A9 induces autophagy and apoptosis via ROS-mediated cross-talk between mitochondria and lysosomes that involves BNIP3. Cell Res 20: 314–331, 2010. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghavami S, Mutawe MM, Sharma P, Yeganeh B, McNeill KD, Klonisch T, Unruh H, Kashani HH, Schaafsma D, Los M, Halayko AJ. Mevalonate cascade regulation of airway mesenchymal cell autophagy and apoptosis: a dual role for p53. PLoS One 6: e16523, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghavami S, Sharma P, Yeganeh B, Ojo OO, Jha A, Mutawe MM, Kashani HH, Los MJ, Klonisch T, Unruh H, Halayko AJ. Airway mesenchymal cell death by mevalonate cascade inhibition: integration of autophagy, unfolded protein response and apoptosis focusing on Bcl2 family proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843: 1259–1271, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghavami S, Yeganeh B, Stelmack GL, Kashani HH, Sharma P, Cunnington R, Rattan S, Bathe K, Klonisch T, Dixon IM, Freed DH, Halayko AJ. Apoptosis, autophagy and ER stress in mevalonate cascade inhibition-induced cell death of human atrial fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis 3: e330, 2012. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girodet PO, Ozier A, Bara I, Tunon de Lara JM, Marthan R, Berger P. Airway remodeling in asthma: new mechanisms and potential for pharmacological intervention. Pharmacol Ther 130: 325–337, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol 221: 3–12, 2010. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halwani R, Al-Muhsen S, Hamid Q. Airway remodeling in asthma. Curr Opin Pharmacol 10: 236–245, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Logue SE, Sayen MR, Jinno M, Kirshenbaum LA, Gottlieb RA, Gustafsson AB. Response to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury involves Bnip3 and autophagy. Cell Death Differ 14: 146–157, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan M, Jo T, Risse PA, Tolloczko B, Lemière C, Olivenstein R, Hamid Q, Martin JG. Airway smooth muscle remodeling is a dynamic process in severe long-standing asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125: 1037–1045, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hesselink MK, Schrauwen-Hinderling V, Schrauwen P. Skeletal muscle mitochondria as a target to prevent or treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 12: 633–645, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hornig-Do HT, Günther G, Bust M, Lehnartz P, Bosio A, Wiesner RJ. Isolation of functional pure mitochondria by superparamagnetic microbeads. Anal Biochem 389: 1–5, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikeda Y, Shirakabe A, Maejima Y, Zhai P, Sciarretta S, Toli J, Nomura M, Mihara K, Egashira K, Ohishi M, Abdellatif M, Sadoshima J. Endogenous Drp1 mediates mitochondrial autophagy and protects the heart against energy stress. Circ Res 116: 264–278, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jheng HF, Tsai PJ, Guo SM, Kuo LH, Chang CS, Su IJ, Chang CR, Tsai YS. Mitochondrial fission contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Biol 32: 309–319, 2012. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05603-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaim G, Dimroth P. ATP synthesis by F-type ATP synthase is obligatorily dependent on the transmembrane voltage. EMBO J 18: 4118–4127, 1999. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaminska M, Foley S, Maghni K, Storness-Bliss C, Coxson H, Ghezzo H, Lemière C, Olivenstein R, Ernst P, Hamid Q, Martin J. Airway remodeling in subjects with severe asthma with or without chronic persistent airflow obstruction. J Allergy Clin Immunol 124: 45–51.e4, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy, cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting pathway, and pexophagy in yeast and mammalian cells. Annu Rev Biochem 69: 303–342, 2000. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubli DA, Ycaza JE, Gustafsson AB. Bnip3 mediates mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death through Bax and Bak. Biochem J 405: 407–415, 2007. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laporte JC, Moore PE, Baraldo S, Jouvin MH, Church TL, Schwartzman IN, Panettieri RA Jr, Kinet JP, Shore SA. Direct effects of interleukin-13 on signaling pathways for physiological responses in cultured human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 141–148, 2001. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2008060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laporte JD, Moore PE, Panettieri RA, Moeller W, Heyder J, Shore SA. Prostanoids mediate IL-1β-induced β-adrenergic hyporesponsiveness in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 275: L491–L501, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee Y, Lee HY, Hanna RA, Gustafsson AB. Mitochondrial autophagy by Bnip3 involves Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission and recruitment of Parkin in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1924–H1931, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00368.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell 6: 463–477, 2004. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liesa M, Palacín M, Zorzano A. Mitochondrial dynamics in mammalian health and disease. Physiol Rev 89: 799–845, 2009. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lippai M, Szatmari Z. Autophagy-from molecular mechanisms to clinical relevance. Cell Biol Toxicol 33: 145–168, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10565-016-9374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Levine B. Autosis and autophagic cell death: the dark side of autophagy. Cell Death Differ 22: 367–376, 2015. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manson ML, Säfholm J, Al-Ameri M, Bergman P, Orre AC, Swärd K, James A, Dahlén SE, Adner M. Bitter taste receptor agonists mediate relaxation of human and rodent vascular smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol 740: 302–311, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyerhof W, Batram C, Kuhn C, Brockhoff A, Chudoba E, Bufe B, Appendino G, Behrens M. The molecular receptive ranges of human TAS2R bitter taste receptors. Chem Senses 35: 157–170, 2010. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjp092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minet AD, Gaster M. ATP synthesis is impaired in isolated mitochondria from myotubes established from type 2 diabetic subjects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 402: 70–74, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Misior AM, Yan H, Pascual RM, Deshpande DA, Panettieri RA, Penn RB. Mitogenic effects of cytokines on smooth muscle are critically dependent on protein kinase A and are unmasked by steroids and cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol 73: 566–574, 2008. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.04077519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev 21: 2861–2873, 2007. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore PE, Lahiri T, Laporte JD, Church T, Panettieri RA Jr, Shore SA. Selected contribution: synergism between TNF-alpha and IL-1 beta in airway smooth muscle cells: implications for beta-adrenergic responsiveness. J Appl Physiol (1985) 91: 1467–1474, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore PE, Laporte JD, Gonzalez S, Moller W, Heyder J, Panettieri RA Jr, Shore SA. Glucocorticoids ablate IL-1beta-induced beta-adrenergic hyporesponsiveness in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 277: L932–L942, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, Dann SG, Kim SY, Gulati P, Byfield MP, Backer JM, Natt F, Bos JL, Zwartkruis FJ, Thomas G. Amino acids mediate mTOR/raptor signaling through activation of class 3 phosphatidylinositol 3OH-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 14238–14243, 2005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506925102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan S, Berk BC. Glutathiolation regulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced caspase-3 cleavage and apoptosis: key role for glutaredoxin in the death pathway. Circ Res 100: 213–219, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000256089.30318.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan S, Wang N, Bisetto S, Yi B, Sheu SS. Downregulation of adenine nucleotide translocator 1 exacerbates tumor necrosis factor-α-mediated cardiac inflammatory responses. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H39–H48, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00330.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Papandreou ME, Tavernarakis N. Autophagy and the endo/exosomal pathways in health and disease. Biotechnol J 12: 1600175, 2017. doi: 10.1002/biot.201600175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Penn RB, Pronin AN, Benovic JL. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Trends Cardiovasc Med 10: 81–89, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(00)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perkins GA, Sun MG, Frey TG. Chapter 2 Correlated light and electron microscopy/electron tomography of mitochondria in situ. Methods Enzymol 456: 29–52, 2009. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04402-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pulkkinen V, Manson ML, Säfholm J, Adner M, Dahlén SE. The bitter taste receptor (TAS2R) agonists denatonium and chloroquine display distinct patterns of relaxation of the guinea pig trachea. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L956–L966, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00205.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quinsay MN, Lee Y, Rikka S, Sayen MR, Molkentin JD, Gottlieb RA, Gustafsson AB. Bnip3 mediates permeabilization of mitochondria and release of cytochrome c via a novel mechanism. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 1146–1156, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saxena H, Deshpande DA, Tiegs BC, Yan H, Battafarano RJ, Burrows WM, Damera G, Panettieri RA, Dubose TD Jr, An SS, Penn RB. The GPCR OGR1 (GPR68) mediates diverse signalling and contraction of airway smooth muscle in response to small reductions in extracellular pH. Br J Pharmacol 166: 981–990, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma P, Panebra A, Pera T, Tiegs BC, Hershfeld A, Kenyon LC, Deshpande DA. Antimitogenic effect of bitter taste receptor agonists on airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 310: L365–L376, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00373.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimizu S, Kanaseki T, Mizushima N, Mizuta T, Arakawa-Kobayashi S, Thompson CB, Tsujimoto Y. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in a non-apoptotic programmed cell death dependent on autophagy genes. Nat Cell Biol 6: 1221–1228, 2004. doi: 10.1038/ncb1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shirakabe A, Zhai P, Ikeda Y, Saito T, Maejima Y, Hsu CP, Nomura M, Egashira K, Levine B, Sadoshima J. Drp1-Dependent Mitochondrial Autophagy Plays a Protective Role Against Pressure Overload-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Heart Failure. Circulation 133: 1249–1263, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toledo FG, Watkins S, Kelley DE. Changes induced by physical activity and weight loss in the morphology of intermyofibrillar mitochondria in obese men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 3224–3227, 2006. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tracy K, Dibling BC, Spike BT, Knabb JR, Schumacker P, Macleod KF. BNIP3 is an RB/E2F target gene required for hypoxia-induced autophagy. Mol Cell Biol 27: 6229–6242, 2007. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02246-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsurikisawa N, Oshikata C, Tsuburai T, Saito H, Sekiya K, Tanimoto H, Takeichi S, Mitomi H, Akiyama K. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness to histamine correlates with airway remodelling in adults with asthma. Respir Med 104: 1271–1277, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X, Su B, Fujioka H, Zhu X. Dynamin-like protein 1 reduction underlies mitochondrial morphology and distribution abnormalities in fibroblasts from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Am J Pathol 173: 470–482, 2008. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, Li X, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 29: 9090–9103, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu T, Sheu SS, Robotham JL, Yoon Y. Mitochondrial fission mediates high glucose-induced cell death through elevated production of reactive oxygen species. Cardiovasc Res 79: 341–351, 2008. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]