Abstract

Background

Celiac disease (CD) is a common immune-mediated disorder that affects up to 1% of the general population. Recent reports suggest that the incidence of CD has reached a plateau in many countries. We aim to study the incidence and altered presentation of childhood CD in a well-defined population.

Methods

Using the Rochester Epidemiology Project, we retrospectively reviewed Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center medical records from January 1994 to December 2014. We identified all CD cases of patients aged 18 or younger at the time of diagnosis. Incidence rates were calculated by adjusting for age, sex, and calendar year and standardizing to the 2010 US white population.

Results

We identified 100 patients with CD. Incidence of CD has increased from 8.1 per 100,000 person-years (2000–2002) to 21.5 per 100,000 person-years (2011–2014). There was an increase in CD prevalence in children from 2010 (0.10%) to 2014 (0.17%). Thirty-four patients (34%) presented with classical CD symptoms, 43(43%) had non-classical CD, and 23(23%) were diagnosed by screening asymptomatic high-risk patients. Thirty-six patients (36%) had complete villous atrophy, 51 (51%) had partial atrophy, 11 (11%) had increased intraepithelial lymphocytes. Two patients were diagnosed without biopsy. Most patients (67%) had a normal body mass index, 17% were overweight/obese and only 9% were underweight.

Conclusion

Both incidence and prevalence of CD have continued to increase in children over the past 15 years in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clinical and pathologic presentations of CD are changing over time (more non-classical and asymptomatic cases are emerging).

Keywords: celiac, epidemiology, incidence, prevalence

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is one of the most common immune-mediated disorders in both children and adults.[1] In CD patients, consuming grain-containing gluten will result in characteristic histologic changes in the small bowel.[2] CD primarily affects individuals of northern European descent, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3% in North America and Europe.[3–7] According to the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN), CD diagnostic guidelines in both adults and children require positive serologic markers followed by a confirmatory small bowel biopsy (SBB) with characteristic histologic features.[2, 8] The most recent guidelines from the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) suggested the possibility of omitting the confirmatory SBB in children who meet specific criteria, particularly those with symptoms of CD.[9]

The occurrence of CD varies widely across the literature.[10] Based on many epidemiologic studies, including the data from Olmsted County, Minnesota, in the US, prevalence and incidence of CD increased considerably between 1950 and 2001.[11–13] It is not clear if this was a true increase in occurrence or was secondary to the availability of more sensitive testing like anti-tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A antibodies (tTG IgA), or was due to increased awareness and screening of CD. Recent reports from Finland and Italy suggest that the previously observed increments in CD incidence in children has plateaued, while other reports from Scotland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom suggest that the incidence is still increasing.[4, 12, 14–17]

It is known that symptomatic CD patients only represent the tip or the celiac iceberg.[18] CD presents with different clinical manifestations at different ages. Diarrhea and failure to thrive are common in infants and young children, and extra intestinal manifestations are more common in older children and adolescents.[19] The clinical presentation of CD in children and adolescents has been divided into classical and non-classical presentation. Classical CD usually presents with signs and symptoms of malabsorption, such as diarrhea and poor growth,[20] whereas non-classical CD presents with non-specific gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (eg, non-specific abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and constipation) and/or extra GI manifestations (eg, oral ulcers, hepatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, iron deficiency anemia, and unexplained bone fractures).[2, 21–23] Over the past decade, more children are presenting with non-classical presentation of CD.[20, 24] Furthermore, recent data suggests that up to 19% of children with a new CD diagnosis are overweight or obese.[25]

The majority of CD patients are still undiagnosed, despite increased awareness and the availability of very sensitive serologic testing.[26] In an effort to identify asymptomatic patients with CD, many high-risk patients, like those with a family history of CD, diabetes mellitus type 1 (DM1), thyroid disease, immunoglobulin (IgA) deficiency, and Down syndrome, are being screened regardless of their symptoms.[27]

We performed a retrospective cohort study aimed at examining the trends in incidence and prevalence of childhood CD in Olmsted County, Minnesota. We assessed the change in clinical and histologic presentation of CD over the past 14 years.

Methods

Setting

We conducted our study in Olmsted County, which is located in southeastern Minnesota, in the United States. The Olmsted County population has the same age, sex, and ethnic characteristics of Minnesota in general, with a majority of non-Hispanic whites (82%) and small minorities of African American (6%), Asian (6%), Hispanic (5%) and mixed ethnicities (1%).[28] Olmsted County provides an exceptional location to perform population-based studies such as this because almost all Olmsted County, MN residents, their all inpatient and outpatient medical events and health care providers are linked and retrieved for research under the auspices of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) starting in 1966.[29, 30] Since then, the REP has been continuously supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) which provides a continuously updated database from Olmsted County’s 2 main health care providers: Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center.[29, 30] We used the REP database to search for potential CD cases using ICD-9 code: 579.0. We also screened the databases of previous studies conducted in Olmsted County for potential cases.[13, 31]

Case Ascertainment and Characterization

After obtaining approval from the institutional review boards of Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center, we retrospectively reviewed the records of Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center for our cohort of potential cases. The index date was defined as the date of clinical diagnosis. We identified all patients aged 18 years or younger with an index date between January 1, 1994, and December 31, 2014, who met the NASPGHAN or ESPGHAN guidelines for CD diagnosis.[2, 8, 32] Incidence was calculated between 2000 and 2014, and charts from 1994–1999 were reviewed only to calculate prevalence. The following data were collected from the charts: birthdate, race, sex, date of diagnosis, family history of CD, body mass index (BMI) at index date, clinical presentations at the time of diagnosis, CD-specific antibodies tests, and IgA levels. Pathology reports of SBB where reviewed by one author (E.A.). The degree of mucosal injury on the SBB was classified as normal, increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) without villous atrophy, partial villous atrophy, or complete villous atrophy.[33] CD cases were categorized into 3 groups based on the presenting symptoms at the time of diagnosis. The first group included children with symptoms of malabsorption (classical CD). The second group included children with other non-specific gastrointestinal or extra-gastrointestinal symptoms (non-classical CD). The third group included asymptomatic children diagnosed based on screening of high-risk groups for CD.[20]

Patients’ growth parameters were reported following the current guidelines that recommend assessing body weight percentiles in children according to their age and sex. For children younger than 24 months, we used World Health Organization standards to determine the weight for length (W/L) percentile [34]. For children 25 months or older, we used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth charts to get the BMI percentile.[35]

Inclusion Criteria

Positive CD serology markers such tTG IgA antibodies, antiendomysial antibodies (EMA), or deamidated gliadin peptide antibodies (DGP).

Confirmatory SBB with CD characteristic histologic findings (eg, increase in IEL, villous atrophy, and crypts hyperplasia)[33] or no SBB but meets the ESPGHAN criteria for avoiding the SBB.

Authorization for using medical records for research.

Many CD cases in this study were diagnosed by the principal investigator (I.A). Olmsted County residency was confirmed electronically using the REP database. Cases were considered incident if the patient was living in Olmsted County at the time of diagnosis to exclude referral cases seeking tertiary care. For prevalence cases, we considered all patients (even those diagnosed elsewhere) and verified their place of residency and their age both on January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2014.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients who were older than 18 years at time of diagnosis, had negative SBB, or didn’t have confirmatory SBB without meeting ESPGHAN criteria for omitting SBB were excluded. Subjects who declined permission for use of their medical records for research purposes were excluded from this study as required by Minnesota state law (Supplemental Digital Content 1).[36]

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for categorical variables are reported as number (percentage) and continuous variables as median (IQR). Age-, sex-, and calendar-year–specific incidence rates of CD diagnosed with biopsy (or ESPGHAN criteria) were calculated by using the number of new pediatric patients (≤18 years) who were living in Olmsted County at the time of diagnosis as the numerator, while the denominator was based on REP census data, assuming that all children were at risk. Incidence rates were standardized to the 2010 US white population. The 95% CIs for incidence rates assumed the number of cases followed a Poisson distribution. The association of age, sex, and calendar year were accessed with multivariable Poisson regression. The functional form of calendar year was tested with linear trend contrasts, and the functional form of age was tested with Loess smoothing plots. Incidence rates were calculated by sex for 3 age categories (0–5, 6–14, and 15–18), with 3-year intervals. Generalized linear models (cumulative and binary logistic regression where appropriate) were utilized to test associations of presenting symptoms and villous atrophy with age, sex, and calendar year. Chi-square and Fisher Exact tests were used for the associations of presenting symptoms, villous atrophy, and BMI where appropriate. Data were analyzed using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA). An alpha level of .05 was used as the level of statistical significance.

Results

Study Subjects

We identified a total of 102 confirmed CD patients who met our inclusion criteria (100 underwent SBB and 2 were diagnosed without SBB according to the new ESPGHAN guidelines)[9]. Two patients were diagnosed outside of Olmsted County but subsequently moved to Olmsted at the time of our prevalence dates. Therefore, there were 100 incident cases between 2000 and 2014. Demographic characteristics of our incidence cohort are shown in Table 1. At the time of diagnosis, 23 (%) children were ≤5 years, 65 (%) were between 6–14 years, and 12 (%) were ≥15 years with 59 (%) female patients. About half (49%) of the incident cases included in this study were diagnosed in the last 5 years of the study, between 2010 and 2014. Only 20 (%) of the included incidence cases had their DGP antibodies checked and 26 (%) had the CD associated human leukocyte antigen (HLA) status checked.

Table 1.

Patients Characteristics

| Variable | Overall (N=100) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis (Q1, Q3) | 9.5 | (6.2, 12.8) |

| White, No. (%) | 95 | (95) |

| African American, No. (%) | 4 | (4) |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 1 | (1) |

| Male, No. (%) | 41 | (41) |

| Incident CD cases (after 2009), No. (%) | 49 | (49) |

| Prevalent CD cases, January 2010, No. (%) | 37 | (37) |

| Prevalent CD cases, December 2014, No. (%) | 64 | (64) |

| Family history of celiac disease, No. (%) | 44 | (44) |

| IgA deficiency, No. (%) | 7 | (7) |

| SBB findings, No. (%) | ||

| Increase in IEL without villous atrophy | 11 | (11) |

| Partial villous atrophy | 51 | (52) |

| Complete villous atrophy | 36 | (37) |

Temporal Trend of Incidence

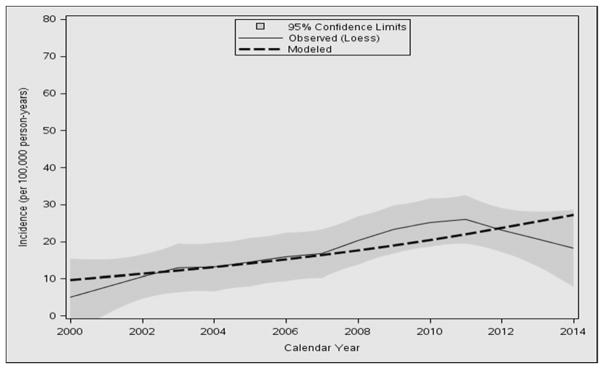

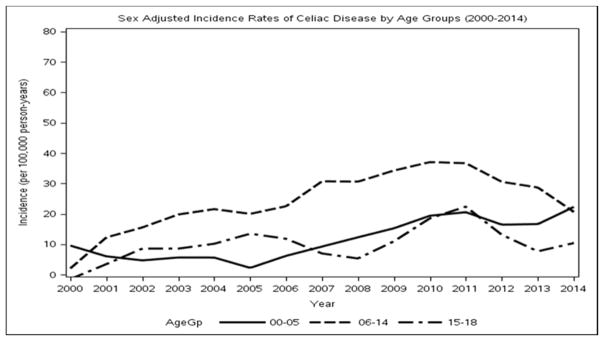

In the period from 2000 through 2014, the overall annual age- and sex-adjusted standardized incidence rate of CD was 17.4 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI, 14.0–20.8). Between 2000 and 2002, the annual adjusted incidence rate was 8.2 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI, 2.8–13.3), while the incidence rate rose to its highest peak between 2009 and 2011, with 25.7 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI, 16.4–34.9). The increase in incidence appeared to be linear over time (P=0.004) (Figure 1), with no interactions with age or sex. The functional form of age was observed to be quadratic because there was high incidence in 6–14 year olds but a lower incidence for toddlers and high school–aged patients (Figure 2). When added to a Poisson model including sex and linear calendar year, quadratic age was significant (P<0.001). Sex was also a significant predictor of the number of incidence cases, with females having a higher incidence (P=0.04) (Supplemental Digital Content 2). Detailed incidence information is presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Loess smooth of incidence of pediatric celiac disease and shaded 95% confidence limits with modeled linear trend as dashed line.

Figure 2.

Loess smooth of calendar-year trends of incidence by age groups.

Table 2. Incidence of Celiac Disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 2000–2014 According to Age Group, Sex, and Time Period.

[Age group–specific results were summarized with number (unadjusted incidence rate) and “all ages” results had number (age-adjusted incidence rate). The total section contains numbers (sex-adjusted incidence rates) for both sexes. All rates were per 100,000 person-years and standardized to the 2010 US white population, and all age-adjusted rates were presented with 95% CIs.]

| Age Group, y | 2000–2002 (n=9) | 2003–2005 (n=15) | 2006–2008 (n=20) | 2009–2011 (n=30) | 2012–2014 (n=26) | 2000–2014 (n=100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | ||||||

| 0–5 | 1 (5.7) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.0) | 6 (29.5) | 6 (30.0) | 15 (15.5) |

| 6–14 | 3 (11.9) | 7 (28.2) | 10 (39.9) | 11 (42.1) | 7 (25.7) | 38 (29.6) |

| 15–18 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.0) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (17.4) | 2 (18.1) | 6 (10.1) |

| All ages | 7.7 (0.2, 15.2) | 16.6 (5.7, 27.5) | 20.5 (8.4, 32.6) | 33.2 (18.2, 48.2) | 25.5 (12.6, 38.5) | 21.0 (15.6, 26.4) |

| Males | ||||||

| 0–5 | 1 (5.5) | 1 (5.1) | 2 (9.4) | 2 (9.2) | 2 (9.4) | 8 (7.8) |

| 6–14 | 3 (11.0) | 3 (11.2) | 5 (18.9) | 7 (25.9) | 9 (31.9) | 27 (19.9) |

| 15–18 | 1 (8.1) | 2 (15.8) | 1 (8.0) | 2 (17.2) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (9.9) |

| All ages | 8.7 (1.1, 16.3) | 10.4 (2.1, 18.7) | 13.6 (4.1, 23.0) | 18.9 (7.7, 30.2) | 18.0 (7.3, 28.6) | 14.0 (9.7, 18.3) |

| Total | ||||||

| 0–5 | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.2) | 3 (7.2) | 8 (19.1) | 8 (19.4) | 23 (11.6) |

| 6–14 | 6 (11.5) | 10 (19.4) | 15 (29.1) | 18 (33.8) | 16 (28.9) | 65 (24.6) |

| 15–18 | 1 (4.1) | 3 (11.9) | 2 (8.1) | 4 (17.3) | 2 (9.0) | 12 (10.0) |

| All ages | 8.1 (2.8, 13.3) | 13.5 (6.7, 20.3) | 17.8 (10.0, 25.7) | 25.7 (16.4, 34.9) | 21.5 (13.2, 29.8) | 17.4 (14.0, 20.8) |

Prevalence

Prevalence of childhood CD in Olmsted County was calculated at 2 points, January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2014. Thirty-nine children with confirmed CD were living in Olmsted County on January 1, 2010, and the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence was 103.6 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI, 71.0–136.2). Prevalence increased in the following 5 years, with 65 cases in Olmsted County and an age- and sex-adjusted prevalence rate of 173.9 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI, 131.4–216.4) on December 31, 2014 although this was not statistically significantly (P= .07). The highest prevalence rate reported in 2010 for males was in the 15–18 year old age group, yet for females the highest prevalence was in the 6–14 year old age group. However, in 2014 the highest prevalence rate reported across sexes was in the high school–age group (15–18 years) (411.1 and 189.8 per 100,000 person-years, respectively), as seen in Supplemental Digital Content 3.

Presenting Symptoms

The most common presenting symptoms in all the 100 incident cases were non-specific GI or extra-GI symptoms (non-classical CD) in 43 (43%) of included patients (Supplemental Digital Content 4). About one-third of patients (34%) presented with diarrhea and/or weight loss (classical CD). The remaining 23 patients (23%) were asymptomatic and were diagnosed as part of our general practice of screening high risk patient (family members, trisomy 21, turner or insulin dependent diabetes) for CD [27]. Sixteen of asymptomatic patients were screened because of family history of CD and seven because of personal history of DM1. The mean age at diagnosis for patients presenting with classical CD was 8.09 years, and the mean age for children who had non-classical CD or were asymptomatic was 10.19 years (P=0.025). The most common non-specific GI symptom was abdominal pain, which was reported in 37 patients, followed by other GI symptoms (Supplemental Digital Content 5). Non-classical CD increased significantly over the years of our study (P=0.004), while both silent CD and classical CD decreased, though classical presentation was not significant (P=0.023 and P=0.32, respectively). Younger children tended to have classical CD (P=0.016), which can explain their younger age at diagnosis. Only two patients had villous atrophy confined to the first portion of the duodenum (Ultrashort CD) and presented with mild non-classic symptoms[37].

Body Weight Assessment

The median BMI percentile was 51 (11–79). Sixty-seven incident cases (67%) had a normal BMI at diagnosis for their age and sex. Three patients (3%) were obese (BMI ≥95th percentile) and 14 (14%) were overweight (BMI ≥85th percentile) at the time of diagnosis. Only 9 (9%) were underweight (BMI <5th percentile). Weight records for 7 (7%) cases were missing. BMI (as categorized by standard definition [34] [35]) was associated with clinical presentation. Specifically, patients with asymptomatic CD were more likely to be overweight or obese than patients with presenting symptoms (P=0.045).

Histopathology Findings

There was no correlation between the degree of villous atrophy on SBB and the type of clinical presentation (P=0.43), which agrees with reports on a lack of association between severity of mucosal damage and clinical presentation.[38] The degree of villous atrophy on the SBB was not found to be significantly related to BMI (P=0.80), age, sex, or calendar year.

Discussion

In this study, we report the epidemiologic characteristics of childhood CD in Olmsted County, Minnesota. The diagnoses were made according to the current North American and European criteria.[8, 9] Unlike the previous epidemiologic studies in Olmsted County, we focused mainly on the pediatric population in this unique community. In the period from 2000 through 2014, 100 children were diagnosed with CD, with a total incidence of 17.4 per 100,000 person-years. We found a significant linear increase in total incidence. This finding is consistent with recent studies from Scotland, the Netherlands, and the UK.4,14–16 It also shows that the previously noticed increase in CD incidence in all ages in Olmsted County,[13, 31] from 1950 to 2001 and 2001 to 2010, has continued in children through 2014. The prevalence of CD in children has increased from 0.10% in 2010 to 0.17% in 2014. This prevalence is one of the highest in the current literature in this age category.[4]

The underlying etiology for the increase in CD occurrence is unknown. Similar increase has been reported in other autoimmune diseases in children, such as DM1 which suggests the possibility of true increase in CD occurrence [39]. On the other hand, the availability of very sensitive serologic tests, screening of high risk patients, and the increased awareness of CD between medical providers and families may play a role in the apparent increase in the incidence and prevalence.

Based on the serology screening tests, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) shows that the national CD prevalence in children between 6 and 18 years in the United States was 0.59% in 2011 and 2012.[40] Compared to our result in Olmsted County, we think there is a gap between the prevalence of clinically diagnosed CD and the prevalence of CD found by screening tests. As a result, many silent and non-classical CD cases are still undiagnosed despite the presence of excellent health care and a high awareness of CD in the small community of Olmsted County.

Ninety-eight (98%) of our cases met the NASPGHAN criteria. Only 2 patients (2%) were diagnosed without SBB according to the new ESPGHAN guidelines. Out of the 15 patients who were diagnosed after the ESPGHAN guidelines were published in 2012, SBB was avoided in only 1 patient (the other patient diagnosed without SBB was in 2008). As a result, most pediatricians in Olmsted County are still using SSB as the gold standard for CD diagnosis. New diagnostic tests have been introduced over the past few years, including the DGP antibodies as new serologic markers and the assessment of CD associated HLA status in difficult cases.[41–43] These tests were performed in small number of our included cases, that could be due to the tests being relatively new or being performed in difficult cases only.

According to a previous study in Olmsted County prior to 2001, all CD patients were symptomatic, and the majority presented with classical malabsorptive symptoms of CD.[13] After 2000, two-thirds of CD patients presented with non-classical symptoms or were diagnosed by screening of high-risk patients with DM1 or family history of CD. Moreover, only 9% of included cases were underweight at the time of diagnosis. These results affirm the previous studies that suggest a change in the classical malabsorptive picture of CD in children to a more subtle presentation. These studies suggest that more children with CD are presenting with non-classical symptoms, and up to 19% are overweight or obese.[25, 44, 45]

In a previous study in Olmsted County between 1950 and 2001, most patients had complete villous atrophy on the SBB.[13] In our study, however, only 37% of our pediatric cohort had complete villous atrophy, and most patients had partial villous atrophy or only an increase in IEL in the period from 2000 through 2014. This trend can be the result of increased awareness of CD and the availability of sensitive tests resulting in earlier detection and diagnosis.

Limitations and Strengths

Our study has a few limitations, including the inherent limitations as a retrospective study, the small number of incident cases despite the population-based study, and the demographic of Olmsted County, where more than 80% of the population were white. It is also possible that some patients started a gluten-free diet without medical intervention or evaluation. Our study has a few important strengths. First, our study was a population-based study. Second, our study setting has unique epidemiological advantages for retrospective population-based studies including self-contained health care environment and medical record linkage system through the REP for the almost entire Olmsted County population. Lastly, our case ascertainment was based on clinical criteria and pathology.

Conclusion

CD incidence and prevalence continue to increase in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clinical presentation and epidemiological profile of CD are changing, specifically presenting with non-classic milder clinical and pathological findings. Large properly designed population based prospective studies are needed, in order to ascertain the actual changes in the incidence and clinical presentation of CD.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Flow chart

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Scatter plot of the total number of incident cases versus age with the Loess smooth of total cases stratified by sex.

Supplemental Digital Content 3: Prevalence of Celiac Disease in Olmstead County, Minnesota, according to Age Group and Sex [Age group–specific results were summarized with number (unadjusted prevalence rate) and “all ages” results had number (age-adjusted prevalence rate). The total section contains the numbers (sex-adjusted prevalence rates) for both sexes. All rates were per 100,000 person-years and standardized to the 2010 US white population and all age adjusted-rates were presented with 95% CIs.]

Supplemental Digital Content 4. Reasons for testing for celiac disease.

Supplemental Digital Content 5. Non-malabsorptive gastrointestinal symptoms in non-classical celiac disease patients.

What is known?

Celiac disease presentation is changing

Occurrence of celiac disease has been variable between different regions

What is new?

Incidence and prevalence of CD have continued to increase in children over the past 15 years in Olmsted County, Minnesota.

Clinical and pathologic presentations of CD are changing over time (more non-classical and asymptomatic cases are emerging)

Abbreviations

- ACG

American College of Gastroenterology

- BMI

body mass index

- CD

celiac disease

- DGP

anti deamidated gliadin peptide

- DM1

diabetes mellitus type 1

- EMA

endomysial antibodies

- ESPGHN

European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GI

gastrointestinal

- IEL

intraepithelial lymphocytes

- IQR

interquartile range

- NASPGHAN

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- REP

Rochester epidemiology project

- SBB

small bowel biopsy

- tTG IgA

anti-tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A antibodies

- W/L

weight for length

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

Author contributions: Dr. Almallouhi undertook the data collection and wrote the initial draft. Drs. Patel, Wi, and Juhn participated in the conceptual design of the study, and reviewed the manuscript. Dr. Murray interpreted the results and critically reviewed the manuscript. K. King did the statistical analysis. Dr. Absah designed the study, interpreted the results, helped draft the initial manuscript, and reviewed the manuscript.

Grant Support: None

References

- 1.Catassi C, et al. Natural history of celiac disease autoimmunity in a USA cohort followed since 1974. Annals of medicine. 2010;42(7):530–8. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.514285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubio-Tapia A, et al. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013;108(5):656–76. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79. quiz 677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green PH. Where are all those patients with Celiac disease? The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007;102(7):1461–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang JY, et al. Systematic review: worldwide variation in the frequency of coeliac disease and changes over time. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2013;38(3):226–45. doi: 10.1111/apt.12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill ID. Celiac disease--a never-ending story? The Journal of pediatrics. 2003;143(3):289–91. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji J, et al. Incidence of celiac disease among second-generation immigrants and adoptees from abroad in Sweden: evidence for ethnic differences in susceptibility. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2011;46(7–8):844–848. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.579999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myleus A, et al. Celiac disease revealed in 3% of Swedish 12-year-olds born during an epidemic. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2009;49(2):170–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31818c52cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill ID, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2005;40(1):1–19. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Husby S, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2012;54(1):136–60. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821a23d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gujral N, Freeman HJ, Thomson ABR. Celiac disease: Prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2012;18(42):6036–6059. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choung RS, et al. Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in gluten-sensitive problems in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys from 1988 to 2012. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2015;110(3):455–61. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kivela L, et al. Presentation of Celiac Disease in Finnish Children Is No Longer Changing: A 50-Year Perspective. The Journal of pediatrics. 2015;167(5):1109–1115 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray JA, et al. Trends in the identification and clinical features of celiac disease in a North American community, 1950–2001. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2003;1(1):19–27. doi: 10.1053/jcgh.2003.50004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angeli G, et al. An epidemiologic survey of celiac disease in the Terni area (Umbria, Italy) in 2002–2010. Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene. 2012;53(1):20–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burger JPW, et al. Rising incidence of celiac disease in the Netherlands; an analysis of temporal trends from 1995 to 2010. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2014;49(8):933–941. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.915054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White LE, et al. The rising incidence of celiac disease in Scotland. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):e924–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.West J, et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Celiac Disease and Dermatitis Herpetiformis in the UK Over Two Decades: Population-Based Study. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014;109(5):757–768. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catassi C, et al. The coeliac iceberg in Italy. A multicentre antigliadin antibodies screening for coeliac disease in school-age subjects. Acta paediatrica. 1996;412:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Amico MA, et al. Presentation of Pediatric Celiac Disease in the United States: Prominent Effect of Breastfeeding. Clinical Pediatrics. 2005;44(3):249–258. doi: 10.1177/000992280504400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludvigsson JF, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2012 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301346. gutjnl-2011–301346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green PH. The many faces of celiac disease: clinical presentation of celiac disease in the adult population. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Suppl 1):S74–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavak US, et al. Bone Mineral Density in Children With Untreated and Treated Celiac Disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2003;37(4):434–436. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mora S, et al. Effect of gluten-free diet on bone mineral content in growing patients with celiac disease. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1993;57(2):224–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tapsas D, et al. The clinical presentation of coeliac disease in 1030 Swedish children: Changing features over the past four decades. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2016;48(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reilly NR, et al. Celiac disease in normal-weight and overweight children: clinical features and growth outcomes following a gluten-free diet. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2011;53(5):528–31. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182276d5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nenna R, et al. The celiac iceberg: characterization of the disease in primary schoolchildren. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2013;56(4):416–21. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31827b7f64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fasano A, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Archives of internal medicine. 2003;163(3):286–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.St Sauver JL, et al. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2012;87(2):151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocca WA, et al. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2012;87(12):1202–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1996;71(3):266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludvigsson JF, et al. Increasing incidence of celiac disease in a North American population. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013;108(5):818–824. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Husby S, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2012;54(1):136–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821a23d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oberhuber G. Histopathology of celiac disease. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2000;54(7):368–372. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(01)80003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WHO Growth Standards Are Recommended for Use in the US for Infants and Children 0 to 2 Years of Age. 2010 Sep 09; [cited 2016 March 01]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/who_charts.htm.

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Growth Charts. 2009 Aug 04; [cited 2016 March 01]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/clinical_charts.htm.

- 36.Melton LJ., 3rd The threat to medical-records research. The New England journal of medicine. 1997;337(20):1466–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mooney PD, et al. Clinical and Immunologic Features of Ultra-Short Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(5):1125–34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marsh MN, Crowe PT. Morphology of the mucosal lesion in gluten sensitivity. Bailliere’s clinical gastroenterology. 1995;9(2):273–93. doi: 10.1016/0950-3528(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipman TH, et al. Increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes in youth: twenty years of the Philadelphia Pediatric Diabetes Registry. Diabetes care. 2013;36(6):1597–603. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubio-Tapia A, et al. The Prevalence of Celiac Disease in the United States. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2012;107(10):1538–1544. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugai E, et al. Accuracy of Testing for Antibodies to Synthetic Gliadin–Related Peptides in Celiac Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;4(9):1112–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amarri S, et al. Antibodies to Deamidated Gliadin Peptides: An Accurate Predictor of Coeliac Disease in Infancy. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2013;33(5):1027–1030. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9888-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pallav K, et al. Clinical utility of celiac disease-associated HLA testing. Digestive Diseases & Sciences. 599:2199–206. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3143-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravikumara M, Tuthill DP, Jenkins HR. The changing clinical presentation of coeliac disease. Archives of disease in childhood. 2006;91(12):969–971. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.094045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diamanti A, et al. Celiac Disease and Overweight in Children: An Update. Nutrients. 2014;6(1):207–220. doi: 10.3390/nu6010207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Flow chart

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Scatter plot of the total number of incident cases versus age with the Loess smooth of total cases stratified by sex.

Supplemental Digital Content 3: Prevalence of Celiac Disease in Olmstead County, Minnesota, according to Age Group and Sex [Age group–specific results were summarized with number (unadjusted prevalence rate) and “all ages” results had number (age-adjusted prevalence rate). The total section contains the numbers (sex-adjusted prevalence rates) for both sexes. All rates were per 100,000 person-years and standardized to the 2010 US white population and all age adjusted-rates were presented with 95% CIs.]

Supplemental Digital Content 4. Reasons for testing for celiac disease.

Supplemental Digital Content 5. Non-malabsorptive gastrointestinal symptoms in non-classical celiac disease patients.