Abstract

Increasing evidence indicated that excess salt consumption can impose risks on human health and a reduction in daily salt intake from the current average of approximately 12 g/d to 5–6 g/d was suggested by public health authorities. The studies on mice have revealed that sodium chloride plays a role in the modulation of the immune system and a high-salt diet can promote tissue inflammation and autoimmune disease. However, translational evidence of dietary salt on human immunity is scarce. We used an experimental approach of fixing salt intake of healthy human subjects at 12, 9, and 6 g/d for months and examined the relationship between salt-intake levels and changes in the immune system. Blood samples were taken from the end point of each salt intake period. Immune phenotype changes were monitored through peripheral leukocyte phenotype analysis. We assessed immune function changes through the characterization of cytokine profiles in response to mitogen stimulation. The results showed that subjects on the high-salt diet of 12 g/d displayed a significantly higher number of immune cell monocytes compared with the same subjects on a lower-salt diet, and correlation test revealed a strong positive association between salt-intake levels and monocyte numbers. The decrease in salt intake was accompanied by reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-23, along with enhanced producing ability of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. These results suggest that in healthy humans high-salt diet has a potential to bring about excessive immune response, which can be damaging to immune homeostasis, and a reduction in habitual dietary salt intake may induce potentially beneficial immune alterations.

INTRODUCTION

Mounting evidence for the risks imposed on human health by excess salt consumption has attracted public attention in the past decades. Adult populations in many countries have average daily salt intake of about 12 g.1–3 Most salt-related studies focused on the relation of salt intake with the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease.4–9 It has been estimated on the basis of the results from previous studies that a population-wide reduction in habitual dietary salt intake could markedly decrease the incidence of cardiovascular disease.10 The current public health recommendations in most countries are to reduce salt intake to 5–6 g/d.1–3 However, it is largely unknown if this recommended dietary salt reduction from 12 to 6 g has an effect on other aspects of human health, such as the immune system and immune functions.

Studies on mice have shown that high-salt diet can promote tissue inflammation and autoimmune disease,11–13 which raises the possibility that high salt intake might play an important role in driving the dramatically increased incidence of autoimmune diseases in the past half-century together with other environmental factors and genetic factors.14 Validation of this hypothesis by a randomized controlled trial of the effects of long-term reduction in dietary salt on morbidity and mortality from inflammation or immune function–related disease would provide such confirmative proof. A study of this kind is not available at present and in fact, because of practical difficulties of the long duration and the related high costs it seems unlikely that it can be performed in the near future. And even preliminary translational evidence of dietary salt intake on human immunity is still scarce. Only one recent salt-control study performed in human subjects with a 7-day high-salt diet (≥15 g NaCl/d) followed by a 7-day low-salt diet (≤5 g NaCl/d) reported salt-related immune variation.15 However, it was hard to predict to what extent the results from this study can reflect the influence of habitual dietary salt levels since no similar long-term salt-control study was performed.

On the basis of the current public health recommendations for a modest reduction in salt intake for a long duration, a 205-day salt balance study with stepwise change in dietary salt was performed in the frame of a controlled simulated spaceflight program termed Mars520, which provided a unique opportunity to investigate the effects of dietary salt intake on human immunity under metabolic ward conditions. During the simulation conducted in an enclosed habitat, daily salt intake was solely modified (12, 9, 6 g/d and back to 12 g/d NaCl; see Fig 1, A, Table I) for 30–60 days. We carried out a variety of immune analyses to investigate the effects of long-term modest salt-intake reduction on immune status, and at the same time monitored plasma angiogenic protein vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) level at each salt stage to testify the potential role of macrophages in the regulation of salt homeostasis as suggested by animal studies.16

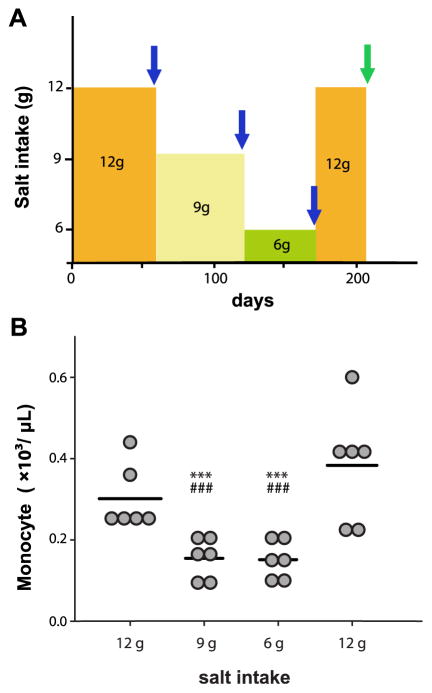

Fig 1.

Salt-intake levels and monocytes. (A) Procedure of the salt-intake study. Blue arrows indicate the time points for both leukocyte phenotype analysis and immune function analysis with ex vivo mitogen stimulation. Green arrow indicates the time point only for complete blood count. (B) Monocyte numbers are decreased with the reduction in salt intake. Monocyte numbers are presented with single subject data. Bars indicate mean values. ***P ≤ 0.001 in comparison with first 12 g salt stage; ###P ≤ 0.001 in comparison with second 12 g salt stage. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Table I.

Nutrients offered during the study (mean ± standard deviation for each salt phase)

| Salt stage | 12 g | 9 g | 6 g | Second 12 g |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main ingredients | ||||

| Kilocalories | 2768 ± 87 | 2788 ± 123 | 2744 ± 68 | 2769 ± 85 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 365 ± 35 | 365 ± 21 | 353 ± 24 | 364 ± 35 |

| Fat (g) | 99 ± 15 | 101 ± 10 | 102 ± 12 | 99 ± 15 |

| Protein (g) | 94 ± 15 | 95 ± 12 | 92 ± 9 | 94 ± 15 |

| Total fiber (g) | 30 ± 7 | 35 ± 6 | 35 ± 6 | 29 ± 7 |

| Minerals | ||||

| Calcium (mg) | 998 ± 112 | 1051 ± 107 | 1093 ± 46 | 1000 ± 14 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 472 ± 74 | 511 ± 55 | 515 ± 60 | 475 ± 73 |

| Potassium (mg) | 3746 ± 598 | 4114 ± 564 | 4494 ± 498 | 3761 ± 620 |

| Sodium (mg) | 4492 ± 505 | 3334 ± 395 | 2196 ± 440 | 4499 ± 493 |

All other nutrients in the diet except for sodium were maintained constant throughout the study (no statistical difference between various salt arms).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Subjects and environmental conditions

This long-term salt-intake study with healthy human subjects was performed in the frame of a spaceflight simulation (Mars520) conducted at the Institute for Biomedical Problems in Moscow and approved by several ethical boards of European Space Agency authorities, the Russian Federation and the University of Munich. Six healthy male volunteers (mean age, 33 ±6 years) were selected based on the modified astronaut selection criteria. They provided written informed consent after due approval to live in an enclosed habitat with well-controlled environmental factors and to perform this salt-intake study and relevant investigations. All participants underwent a thorough clinical examination before participation, and during the study period medical control of their health condition was regularly performed. All studies were done as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Salt-controlled diet

The salt-intake study took place during the first 205 days of the Mars520 mission. Dietary salt reduction was performed stepwise from 12 g salt per day to 9–6 g salt per day. Each salt-intake level was maintained for 50 ±10 days (see Fig 1, A, Table I). The salt-reduction study period was followed by another 12-g period (for 30 days). All other nutrients in the diet were maintained constant throughout the study.

Various European food producers provided more than 200 different food items with preanalyzed nutrient content. Using the PRODI software (Nutri-Science GmbH, Stuttgart, Germany), daily menu plans for each subject were calculated and individualized. The goal of the dietary intervention implemented in the Mars520 project was to maintain all nutrients on a constant level throughout the studies, when only sodium ingestion was altered. During the studies subjects had free access to water, whereas caloric drinks (eg, juices) were limited. More details about the analytical methods of nutritional control have been described elsewhere.17

Blood sampling

Blood samples were drawn into blood tubes containing either ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid or heparin as anticoagulants on waking between 7 and 8 AM at the end point of each salt-intake period. Owing to the limitation on blood drawing in this spaceflight simulation mission (once in 2 months), only complete blood count was performed in the second 12-g period for medical control purpose. The time points for blood sampling during the salt-intake study are shown in Fig 1, A. Differential blood count, immunophenotype analyses, and mitogen stimulation were performed within 1 hour after blood drawing. Plasma samples were immediately frozen at −80°C till the end of the study and shipped on sufficient dry ice to Munich for further measurement.

Differential blood count

White blood cell count and the percentage of each type of white blood cell were measured from whole blood samples immediately after the specimen collection using the Celltac alpha MEK 6318 type full automatic Hematology Analyzer (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunophenotype analysis

Peripheral blood immunophenotype analysis was performed with flow cytometry using the following antibodies (IQ PRODUCTS, Groningen, the Netherlands): CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD16, and CD56 (respective clones: UCHT1, Edu-2, MCD8, HD37, B-E16, and MOC-1). T (CD3+) lymphocytes, B (CD19+) lymphocytes, helper T (CD3+CD4+) lymphocytes, cytotoxic T (CD3+CD8+) lymphocytes, and natural killer (CD3−CD16+and/or CD56+) lymphocytes were identified. The blood samples were processed as described in the manual. The stained leukocytes were analyzed on the FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA) was used to do cell population gating and to run quadrant analysis. Fifteen thousand events were analyzed per tube. Isotypic controls were used for each assay to determine nonspecific staining. The fluorescence compensation was performed using CaliBRITE beads (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) and FACSComp software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA).

Ex vivo mitogen stimulation assay

Pokeweed mitogen (PWM, 5 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) was used for leukocyte stimulation using a previously described method18 with small modification. Whole blood (400 μL) was transferred under aseptic conditions into each tube prefilled with an equal volume (400 μL) of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium Nutrient Mixture F-12 HAM without a further stimulant (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium only) or with PWM. All the assays were performed within 1 hour after blood drawing. The assay tubes were incubated for 48 hours at 37°C, and then the supernatant was transferred into an Eppendorf tube and immediately frozen at −80°C. After completion of the study all the samples were shipped frozen to Munich for cytokine analyses.

Cytokine measurement

Cytokines were measured in a blinded fashion using LuminexxMAP technology (Bioplex) with commercially available reagents from BioRad-Laboratories Inc (Berkeley, California) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Data were analyzed with Bioplex-Software, and assay sensitivities for cytokines IL (interleukin)-10, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-6, and IL-17 were 1.99, 7.35, 0.57, 1.65, and 0.49 pg/mL, respectively. Each assay was performed in duplicate.

VEGF-C measurement

Plasma VEGF-C levels were measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden-Nordernstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Intra-assay and interassay variations in the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay are 6.6% and 8.5%, respectively. Each sample was measured in duplicate.

Statistical methods

All data were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Irrespective of how the data are displayed, changes in each parameter across the salt-intake stages were compared using repeated-measure analyses of variance followed by a post hoc test. Cytokine concentrations in response to mitogen stimulation were transformed to log10 values before comparison because untransformed values were skewed. The log10 values were normally distributed. Data were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. A P value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Correlation analyses were performed with Spearman’s rank correlation. SigmaPlot 12.0 (Systat Software, Chicago, Illinois) was used for data analyses.

RESULTS

Peripheral leukocyte phenotype

Among the leukocyte subgroups analyzed (Table II), both the percentage and the absolute count of monocytes were significantly higher at each 12 g salt stage compared with lower salt levels (P ≤ 0.001), which was observed in all the subjects (Fig 1, B). Correlation analyses indicated monocyte numbers were positively associated with salt-intake levels (Rs = 0.82, P < 0.0001), whereas all the other leukocyte subgroups showed no association with salt levels.

Table II.

Peripheral leukocyte distribution pattern

| Salt stage | 12 g

|

9 g

|

6 g

|

Second 12 g

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | |

| Leukocytes* | 5.508 ± 0.608 | 5.508 ± 0.616 | 5.317 ± 0.434 | 6.292 ± 0.506 |

| Neutrophils | ||||

| % Leukocytes | 50.38 ± 2.67 | 55.46 ± 2.76 | 55.76 ± 2.94 | 48.06 ± 3.22 |

| Absolute count* | 2.830 ± 0.441 | 3.053 ± 0.372 | 3.000 ± 0.353 | 3.062 ± 0.377 |

| Lymphocytes | ||||

| % Leukocytes | 44.13 ± 2.65 | 41.73 ± 2.88 | 41.35 ± 3.04 | 45.95 ± 3.33 |

| Absolute count* | 2.376 ± 0.185 | 2.300 ± 0.328 | 2.163 ± 0.173 | 2.846 ± 0.233 |

| Monocytes | ||||

| % Leukocytes | 5.49 ± 0.08 | 2.82 ± 0.29† | 2.89 ± 0.30† | 5.99 ± 0.61 |

| Absolute count* | 0.301 ± 0.032 | 0.154 ± 0.020† | 0.153 ± 0.019† | 0.384 ± 0.058 |

| CD19+ B cells* | 0.304 ± 0.052 | 0.287 ± 0.042 | 0.207 ± 0.034‡ | n/a |

| CD3+ T cells* | 1.653 ± 0.186 | 1.712 ± 0.248 | 1.582 ± 0.135 | n/a |

| CD3+CD8+ T cells* | 0.490 ± 0.039 | 0.510 ± 0.044 | 0.458 ± 0.046 | n/a |

| CD3+CD4+ T cells* | 0.900 ± 0.172 | 1.006 ± 0.221 | 0.882 ± 0.139 | n/a |

| Natural killer cells* | 0.319 ± 0.062 | 0.311 ± 0.051 | 0.344 ± 0.082 | n/a |

Abbreviation: n/a, Data not available.

Absolute cell counts are × 103 cells/μL.

P ≤ 0.001. P values refer to comparison between values from the first 12 g salt stage and indicated salt stage.

P < 0.05. P values refer to comparison between values from the first 12 g salt stage and indicated salt stage.

Immune response to mitogen stimulation

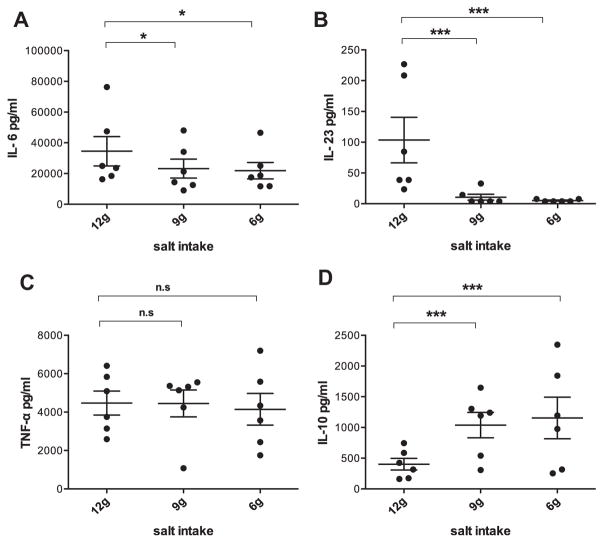

We assessed immune function changes with a focus on the ability to produce representative macrophage proinflammatory cytokines (IL-23, IL-6, and TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10) using an ex vivo PWM stimulation assay. The decrease in salt intake was accompanied by markedly decreased IL-6 and IL-23 production (IL-6, P < 0.05; IL-23, P ≤ 0.001) (Fig 2, A and B). At the 6 g salt stage, the reduction in IL-6 was more than 30% and the reduction in IL-23 was nearly 90% compared with the 12 g salt stage, respectively. Also no changes in TNF-α were detected across the salt levels (Fig 2, C). But the producing ability of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was significantly increased with the reduction in dietary salt (P ≤ 0.001) (Fig 2, D). At the 6 g salt stage, the increase in IL-10 was about three-fold compared with the 12 g salt stage.

Fig 2.

Cytokine production changes with the reduction in salt-intake levels. (A) IL-6, (B) IL-23, (C) TNF-α, and (D) IL-10. Values are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. *A significant decrease (P < 0.05) to that at 12 g stage; ***P ≤ 0.001; n.s., no significant difference. IL, interleukin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

Plasma cytokines

In line with the observation from immune responses, with the reduction in salt intake, circulating IL-6 showed a trend of decrease (P = 0.05) and IL-10 slightly increased (Table III). IL-23 values were largely less than assay sensitivity. We also measured IL-17 in plasma samples because recent reports from the studies on mice suggested that Th17 differentiation was implicated in salt-related immune changes. Interestingly, a tendency was detectable that IL-17 concentration was higher at the 12 g salt stage compared with lower salt levels (P = 0.08). These results were consistent with medical records, which indicated that no systemic inflammation happened during the study period.

Table III.

Plasma cytokines. Summary of plasma cytokine levels

| Salt stage | 12 g

|

9 g

|

6 g

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | |

| TNF-α | 2.618 ± 0.409 | 2.613 ± 0.237 | 2.195 ± 0.215 |

| IL-6 | 3.004 ± 0.487 | 2.257 ± 0.509 | 1.650 ± 0.252 |

| IL-10 | 0.807 ± 0.097 | 0.833 ± 0.048 | 1.782 ± 0.739 |

| IL-17 | 0.635 ± 0.235 | 0.337 ± 0.179 | 0.134 ± 0.017 |

Abbreviations: IL, interleukin; SE, standard error; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

Cytokine concentration is in picograms per milliliter.

IL-6 showed a trend of decrease (P = 0.05).

No significant changes across the salt levels.

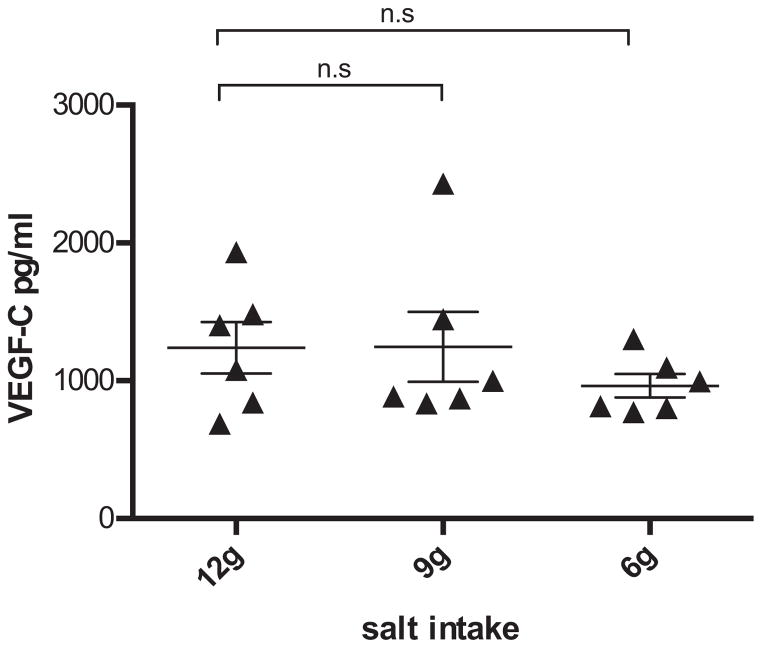

Plasma angiogenic protein VEGF-C

In the plasma samples, we also examined the concentration of VEGF-C because several studies suggest that local hypertonicity can be sensed by macrophages,16,19 and VEGF-C secreted from macrophages is implicated in the salt regulation. The average value of VEGF-C concentration at the 6 g salt stage was lower than that of the 12 and 9 g stages (Fig 3), but no significant changes have been identified across the salt levels.

Fig 3.

Plasma VEGF-C. Values are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. No significant changes have been detected for VEGF-C across the salt stages. VEGF-C, vascular endothelial growth factor C.

DISCUSSION

Twelve grams salt per day represents a high salt intake with excess salt consumption, and it is the average of daily salt intake in many counties.5 The findings from this study might reveal one of the consequences of excess salt consumption in our everyday lives. From this longitudinal salt-intake study, we observed that subjects on the high-salt diet (12 g/d) displayed a markedly higher number of monocytes compared with the same subjects on lower-salt diet, and correlation tests revealed a significant positive association between monocytes and dietary salt in humans. Furthermore, in response to mitogen stimulation, the decrease in salt intake was accompanied by a reduction in proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-23, along with an enhancement in producing ability of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, suggesting subjects on the high-salt diet may have a potential risk of excessive immune response when infection occurs.

Monocytes are the precursors of antigen presenting cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, which bridge innate and adaptive immunity,20–24 and they can all serve as phagocytic cells—the first line of immune defense. Clinically, an increased number of monocytes in the blood are often observed in chronic inflammation, autoimmune disorders, blood disorders, and cancer diseases.25 Also it has been reported that malnutrition such as deficits in zinc may enhance the phagocytic cell numbers.26 The results from a recent short-duration study on changes in dietary salt intake in humans performed with a 7-day high-salt diet followed by a 7-day low-salt diet were largely consistent with the findings from this longitudinal study reporting salt-related immune cell monocyte variations.15 Moreover, Previous salt-intake studies revealed an increased risk of cardiovascular disease with the increase in salt intake.5 Interestingly, it is known that monocytes coexpressing Toll-like receptor 4 are the most abundant inflammatory cell type of innate immunity in cardiovascular disease coronary atherothrombosis.27 Furthermore, dietary sodium restriction is currently the most frequent self-care behavior recommended to patients with heart failure (HF),28 but the underlying mechanism is yet unclear. It is noteworthy that one recent report has given mechanistic insights into the progression of HF, suggesting changes of the mononuclear phagocyte network underlie chronic inflammation and disease progression in HF.29 Our present finding of increase in the percentage and absolute count of monocytes with high-salt diet interestingly corroborated this immune hypothesis of HF. Owing to the absence of previous knowledge about the association between salt-intake levels and monocytes, we could not include systematic measurements of monocyte immune activities in our experimental design of this study. Future investigations are needed to address whether immune activities of monocytes also get affected by salt-intake levels.

Animal experiments have revealed that in addition to playing an important role in the immunity, macrophages could also regulate salt concentration by a VEGF-C–dependent buffering mechanism. In patients with refractory hypertension, plasma VEGF-C concentrations were increased compared with normotensive control subjects.16 In this study, no significant changes in VEGF-C across the salt levels have been observed. We assume in healthy human subjects the effects might have been blanketed by other regulatory pathways seeing that VEGF-C is a functionally highly important protein regulated by multiple redundant pathways.30–34

Immune function analysis showed that compared with the recommended salt-intake level (6 g/d), high-salt diet (12 g/d) was related to higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-23 and lower levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, suggesting that high-salt diet had a potential to bring about excessive immune response. Those can be damaging to the immune homeostasis hereby resulting in either difficulties on getting rid of inflammation or even an increased risk of autoimmune disease. As a preliminary investigation in humans, this study itself could hardly be defined for any investigations on mechanisms on the causative salt-immune interactions, though recent reports from studies on mice have provided us a hint to interpret the observations as such in this study. It was suggested in the murine models that high-salt diet can promote tissue inflammation and autoimmune disease by enhancing Th17 differentiation.11,12 Interestingly, the cytokines that showed significant difference across salt stages in this study—IL-6, IL-23, and IL-10—are critical for both Th17 differentiation and Th17 function,35–45 and the expression of these cytokines is regulated both spatially and temporally. Although for healthy human subjects of this study it is not practical to do cytokine analysis in immune tissues, we assume the cytokine profile changes to a certain extent reflected the cytokine profile alterations in the regulation of local inflammatory response and immune response. Previous investigation also revealed a link between monocyte increase and Th17 population expansion as shown by Rossol et al,46 suggesting a potential mechanism for the excessive immune response along with the high-salt diet in the present study.

This salt-intake study was performed in the frame of a long-term spaceflight simulation study. There were limitations we have to cope with, such as the frequency of blood sampling and limited blood volume. Therefore, only a few immune parameters could be investigated. However, owing to the long duration and high cost, this kind of study is highly difficult to be realized with regular clinical trial. In this study, all the subjects lived in the same environment and had the same food and same exercise schedules, which to the maximum extent ruled out other influential factors.

This longitudinal study reveals an association between salt levels and monocyte numbers, indicating dietary salt changes may lead to significant changes in immune status. Because monocytes/macrophages and related immune functions play important roles in the development of a variety of diseases, the information we achieved from this study might have broad implications for understanding the role of dietary salt in health. These findings raise the possibility that high salt intake might trigger tissue inflammation and autoimmune disease in humans and give insights into sodium chloride as one of the important regulators of immune status, and the results suggest even a small reduction in dietary salt (3 g/d equal to half spoon) might be able to bring about potentially beneficial immune alterations.

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY.

Yi B, et al

Background

It has been revealed in the studies on mice that sodium chloride plays a role in the modulation of the immune system and a high-salt diet can promote tissue inflammation and autoimmune disease. However, translational evidence of dietary salt intake on human immunity is scarce.

Translational Significance

The results have revealed a positive association between dietary salt levels and the amount of immune cell monocytes and suggest that in healthy humans high-salt diet has a potential to trigger excessive immune responses. To our knowledge, these results provided the first translational evidence for the effects of salt-intake levels maintained for a prolonged period on immunity.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have read the journal’s authorship agreement and policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This study was supported by grants from the German Ministry of Technology and Economics (BMWi as handled by DLR) (grant nos. 50WB0919 and 50WB1317). The investigators are thankful to the support from the European Space Agency (ESA), the ESA-ELIPS 4 program, the Institute for Biomedical Problems (IBMP) and the German Space Agency (DLR).

The authors express their appreciation to the international Mars520 crew and all the supporting staff who helped to successfully accomplish this investigation. The study sponsor was not involved in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- HF

heart failure

- IL

interleukin

- PWM

pokeweed mitogen

- TLR

toll-like-receptor

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

- VEGF-C

vascular endothelial growth factor C

References

- 1.Nishida C, Uauy R, Kumanyika S, Shetty P. The joint WHO/FAO expert consultation on diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: process, product and policy implications. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:245–50. doi: 10.1079/phn2003592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He FJ, Jenner KH, Macgregor GA. WASH—world action on salt and health. Kidney Int. 2010;78:745–53. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hulthen L, Aurell M, Klingberg S, Hallenberg E, Lorentzon M, Ohlsson C. Salt intake in young Swedish men. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:601–5. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuchihashi T, Kai H, Kusaka M, et al. [Scientific statement] Report of the Salt Reduction Committee of the Japanese Society of Hypertension (3) Assessment and application of salt intake in the management of hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:1026–31. doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He FJ, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet. 2011;378:380–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA. Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2013;346:f1325. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ando K, Kawarazaki H, Miura K, et al. [Scientific statement] Report of the Salt Reduction Committee of the Japanese Society of Hypertension(1) Role of salt in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:1009–19. doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott P, Walker LL, Little MP, et al. Change in salt intake affects blood pressure of chimpanzees: implications for human populations. Circulation. 2007;116:1563–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappuccio FP. Technical Report. World Health Organization; 2007. Overview and evaluation of national polices, dietary recommendations and programmes around the world aiming at reducing salt intake in the population. Reducing salt intake in populations: report of a WHO forum and technical meeting; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu C, Yosef N, Thalhamer T, et al. Induction of pathogenic TH17 cells by inducible salt-sensing kinase SGK1. Nature. 2013;496:513–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinewietfeld M, Manzel A, Titze J, et al. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature. 2013;496:518–22. doi: 10.1038/nature11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Meer JW, Netea MG. A salty taste to autoimmunity. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2520–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1303292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Shea JJ, Jones RG. Autoimmunity: rubbing salt in the wound. Nature. 2013;496:437–9. doi: 10.1038/nature11959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou X, Zhang L, Ji WJ, et al. Variation in dietary salt intake induces coordinated dynamics of monocyte subsets and monocyte-platelet aggregates in humans: implications in end organ inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machnik A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, et al. Macrophages regulate salt-dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor-C-dependent buffering mechanism. Nat Med. 2009;15:545–52. doi: 10.1038/nm.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rakova N, Juttner K, Dahlmann A, et al. Long-term space flight simulation reveals infradian rhythmicity in human Na(+) balance. Cell Metab. 2013;17:125–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufmann I, Draenert R, Gruber M, Feuerecker M, Roider J, Chouker A. A new cytokine release assay: a simple approach to monitor the immune status of HIV-infected patients. Infection. 2013;41:687–90. doi: 10.1007/s15010-013-0445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller S, Quast T, Schroder A, et al. Salt-dependent chemotaxis of macrophages. PloS One. 2013;8:e73439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morishige K, Kacher DF, Libby P, et al. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging enhanced with superparamagnetic nanoparticles measures macrophage burden in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2010;122:1707–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.891804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fillatreau S. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells identified as booster of T follicular helper cell differentiation. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:574–6. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201404015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakarov S, Fazilleau N. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells promote T follicular helper cell differentiation. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:590–603. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201403841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mauer J, Chaurasia B, Goldau J, et al. Signaling by IL-6 promotes alternative activation of macrophages to limit endotoxemia and obesity-associated resistance to insulin. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:423–30. doi: 10.1038/ni.2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell RS, Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins basic pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders: Elsevier Health Sciences; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraker PJ, King LE. Reprogramming of the immune system during zinc deficiency. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:277–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyss CA, Neidhart M, Altwegg L, et al. Cellular actors, Toll-like receptors, and local cytokine profile in acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1457–69. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riegel B, Moser DK, Powell M, Rector TS, Havranek EP. Nonpharmacologic care by heart failure experts. J Card Fail. 2006;12:149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ismahil MA, Hamid T, Bansal SS, Patel B, Kingery JR, Prabhu SD. Remodeling of the mononuclear phagocyte network underlies chronic inflammation and disease progression in heart failure: critical importance of the cardiosplenic axis. Circ Res. 2014;114:266–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirakawa S, Brown LF, Kodama S, Paavonen K, Alitalo K, Detmar M. VEGF-C-induced lymphangiogenesis in sentinel lymph nodes promotes tumor metastasis to distant sites. Blood. 2007;109:1010–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Bras B, Barallobre MJ, Homman-Ludiye J, et al. VEGF-C is a trophic factor for neural progenitors in the vertebrate embryonic brain. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:340–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao R, Ji H, Feng N, et al. Collaborative interplay between FGF-2 and VEGF-C promotes lymphangiogenesis and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:15894–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208324109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taimeh Z, Loughran J, Birks EJ, Bolli R. Vascular endothelial growth factor in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:519–30. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang X, Zhang Y, Yang Y, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent spatiotemporal dual roles of placental growth factor in modulation of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13932–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309629110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korn T, Mitsdoerffer M, Croxford AL, et al. IL-6 controls Th17 immunity in vivo by inhibiting the conversion of conventional T cells into Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18460–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809850105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura A, Kishimoto T. IL-6: regulator of Treg/Th17 balance. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1830–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Han C, Xie B, et al. Rhbdd3 controls autoimmunity by suppressing the production of IL-6 by dendritic cells via K27-linked ubiquitination of the regulator NEMO. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:612–22. doi: 10.1038/ni.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagashima H, Okuyama Y, Asao A, et al. The adaptor TRAF5 limits the differentiation of inflammatory CD4(+) T cells by antagonizing signaling via the receptor for IL-6. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:449–56. doi: 10.1038/ni.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miossec P, Kolls JK. Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:763–76. doi: 10.1038/nrd3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, et al. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:314–24. doi: 10.1038/ni.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abraham C, Cho JH. IL-23 and autoimmunity: new insights into the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:97–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.051407.123757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yosef N, Shalek AK, Gaublomme JT, et al. Dynamic regulatory network controlling TH17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2013;496:461–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee Y, Awasthi A, Yosef N, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:991–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gu Y, Yang J, Ouyang X, et al. Interleukin 10 suppresses Th17 cytokines secreted by macrophages and T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1807–13. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newcomb DC, Boswell MG, Huckabee MM, et al. IL-13 regulates Th17 secretion of IL-17A in an IL-10-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2012;188:1027–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rossol M, Kraus S, Pierer M, Baerwald C, Wagner U. The CD14(bright) CD16+ monocyte subset is expanded in rheumatoid arthritis and promotes expansion of the Th17 cell population. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:671–7. doi: 10.1002/art.33418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]