Abstract

Background

Self-report is often used in identifying gestational diabetes events in epidemiologic studies; however, validity data are limited, with little to no data on self-reported severity or treatment.

Methods

We aimed to assess the validity of self-reported gestational diabetes diagnosis and evaluate the accuracy of glucose diagnosis results and gestational diabetes treatment self-reported at 6 weeks postpartum. Data were from 82 and 83 women with and without gestational diabetes, respectively, within the prospective National Institute Child Health and Human Development Fetal Growth Studies-Singletons (2009–2013). Medical record data were considered the gold standard.

Results

Sensitivity was 95% [95% confidence interval (CI) 88–98] and specificity 100% (95%CI 96–100); four women with gestational diabetes incorrectly reported not having the disease and none of the women without gestational diabetes reported having gestational diabetes. Sensitivity did not vary substantially across maternal characteristics including race/ethnicity. For women who attempted to recall their values (84/159 women), self-reported glucose challenge test results did not differ from the medical records (median difference: 0; interquartile range: 0, 0 mg/dL). Medical records indicated that 42 (54%) of 78 women with confirmed gestational diabetes were treated by diet only and 33 (42%) were treated by medication. All 42 women with diet-treated gestational diabetes correctly reported having had diet and lifestyle modification and 28 (85%) of 33 women with medication-treated gestational diabetes indicated postpartum that they had medication treatment.

Conclusion

At 6 weeks postpartum, regardless of race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status, women accurately recalled whether they had gestational diabetes and, as applicable, their treatment method.

Keywords: Validation, gestational diabetes, pregnancy, self-report

Introduction

Gestational diabetes is glucose intolerance with first onset or recognition during pregnancy. Gestational diabetes impacts approximately 5%–9% of U.S. pregnancies1 and 2%–25% of pregnancies worldwide.2 Epidemiologic studies on risk factors and health consequences of gestational diabetes are increasing; studies often use self-report for disease ascertainment.3, 4 However, validity data for self-reported gestational diabetes are inconsistent, limited among a multi-racial population, or lacking in a contemporary cohort.5, 6 Most importantly, there is limited data as to the quality of self-reported data with respect to gestational diabetes severity. To our knowledge, no study has reported on women’s ability to self-report their glucose challenge test or oral glucose tolerance test results nor is there data on the validity of self-reported method of gestational diabetes treatment. This data is especially critical as emerging evidence suggests that risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as excessive fetal growth, increases on a continuum with exposure to increasing glucose levels in utero7 and the long-term intergenerational impact of exposure to elevated glucose is limited.

Using a racially and socioeconomically diverse cohort with medical record review, we aimed to assess the validity of gestational diabetes diagnosis self-reported at approximately 6 weeks postpartum. In addition, we assessed the validity of self-reported glucose values from the gestational diabetes diagnosis tests, as well as treatment, as measures of disease severity.

Methods

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Fetal Growth Studies-Singleton Cohort, enrolled 2,334 non-obese women with low-risk, singleton pregnancies stratified by four self-identified racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian)8 and 468 obese women (n=2,802 in total). Women without preexisting chronic diseases or medical conditions were enrolled between 8–13 weeks of gestation at 12 U.S. clinical centers (2009–2013). The institutional review board at each participating center approved the study, and participants provided written informed consent.

Medical chart abstraction was available for most of the cohort (92%; n=2,584). Clinical gestational diabetes diagnoses were determined according to standard clinical care at each clinic. Universal screening was prominent during this study period with 90% (n=2,319) of the cohort having undergone screening. Medical record abstraction included clinical glucose challenge and oral glucose tolerance test results and hospital discharge diagnoses from delivery, which indicated if a woman had gestational diabetes treated by “Diet Control,” “Medication,” or “Unknown Control.” All women with a hospital discharge gestational diabetes diagnosis were eligible for the postpartum follow-up visit (n=132; 5%). Women without gestational diabetes were selected for postpartum follow-up based on 1:1 matching of site, race-ethnicity, and age (±5 years) of the women with gestational diabetes. A total of 99 women with gestational diabetes and 104 eligible matched women without gestational diabetes completed the postpartum follow-up visit.

We wanted to employ a stricter research definition of gestational diabetes which also incorporated the oral glucose tolerance test results. We reviewed the oral glucose tolerance test results according to the Carpenter and Coustan criteria as recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists which requires that at least two diagnostic plasma glucose measurements are at or above defined thresholds (fasting: 5.3 mmol/l; 1-h: 10.0 mmol/l; 2-h: 8.6 mmol/l; 3-h: 7.8 mmol/l).9 We created a gold-standard gestational diabetes definition that included women with oral glucose tolerance test results meeting the above criteria or women whose discharge diagnoses indicated that they had medication treated gestational diabetes (n=107; 4%); of these women, 82 with gestational diabetes and 83 of the matched women without gestational diabetes completed the postpartum visit. Our primary analyses on the validation of self-reported gestational diabetes at 6 weeks postpartum were based on this sample.

At 6 weeks postpartum, a structured questionnaire asked women whether they had gestational diabetes during the index pregnancy, as well as details regarding their diagnosis and treatment. Specifically, women were asked, “Have you been told by a doctor or nurse that you had gestational diabetes during the index pregnancy?”; “If you had an initial one-hour screening test, please provide: One hour blood sugar level,” and “If you had the two or three hour oral glucose tolerance test, please provide the following blood sugar levels,” prompting responses for the fasting, 1-hour, 2-hour, and 3-hour results. Women who self-reported gestational diabetes were also asked, “How was your diabetes during pregnancy treated?” with the following response options: “Diet and lifestyle modification; Insulin; Other medication.”

Sociodemographic and gestational diabetes related risk factors were collected at enrollment. Sensitivity and specificity of self-reported gestational diabetes was estimated as compared to the medical record. Using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as applicable, we examined for differences in sensitivity and specificity across maternal and sociodemographic characteristics. Bland-Altman plots were generated to assess the bias between the self-reported and medical record glucose values. All analyses were completed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

The 6 weeks postpartum visit was completed by 82 women with gestational diabetes defined according to the gold standard research definition and 83 of the eligible matched women without gestational diabetes. eTable 1 describes the differences between women with gestational diabetes who completed the postpartum visit and those who did not. At 6 weeks postpartum, gestational diabetes was correctly reported by 78 of 82 women yielding an overall sensitivity of 95% [95% confidence interval (CI) 88–98] (Table). None of the 83 women who did not have gestational diabetes reported postpartum as having gestational diabetes, indicating 100% specificity (95% CI 96–100). Sensitivity of self-reported gestational diabetes did not vary substantially by maternal characteristics including race-ethnicity. According to the medical record, almost all of the women without gestational diabetes had a glucose challenge test (98%) and some (19%) also underwent an oral glucose tolerance test, but had normal values; specificity of self-reported gestational diabetes postpartum did not differ between these women. In addition, sensitivity and specificity did not differ according to the number of abnormal oral glucose tolerance test results (eTable 2).

Table.

Sensitivity and specificity of self-reported gestational diabetes diagnosisa at 6 weeks postpartum according to maternal characteristics among 82 women with gestational diabetes and 83 women without gestational diabetes according to the medical record, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Fetal Growth Studies-Singletons.

| Characteristic | Sensitivity of Self- Reported Gestational Diabetes Diagnosis |

Specificity of Self- Reported Gestational Diabetes Diagnosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | (95% CI)b | n | (%) | (95% CI)c | |

| Overall | 82 | -- | 95% (88–98) | 83 | -- | 100% (96–100) |

| Age, years | ||||||

| ≤24 | 13 | (16) | 100% (77–100) | 15 | (18) | 100% (80–100) |

| 25–29 | 21 | (26) | 95% (77–99) | 26 | (31) | 100% (87–100) |

| 30–34 | 25 | (30) | 92% (75–98) | 28 | (34) | 100% (88–100) |

| ≥35 | 23 | (28) | 96% (79–99) | 14 | (17) | 100% (78–100) |

| Race Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 20 | (24) | 95% (76–99) | 19 | (23) | 100% (83–100) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11 | (13) | 100% (74–100) | 13 | (16) | 100% (77–100) |

| Hispanic | 30 | (37) | 100% (89–100) | 33 | (40) | 100% (90–100) |

| Asian & Pacific Islander | 21 | (26) | 86% (65–95) | 18 | (22) | 100% (82–100) |

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index status | ||||||

| Normal weight | 26 | (32) | 92% (76–98) | 45 | (54) | 100% (92–100) |

| Overweight | 25 | (30) | 96% (80–99) | 19 | (23) | 100% (83–100) |

| Obese | 31 | (38) | 97% (84–99) | 19 | (23) | 100% (83–100) |

| Nulliparous | ||||||

| No | 39 | (48) | 97% (87–100) | 44 | (53) | 100% (92–100) |

| Yes | 43 | (52) | 93% (81–98) | 39 | (47) | 100% (91–100) |

| Prior gestational diabetes among parous women | ||||||

| No | 37 | (95) | 97% (86–100) | 0 | (0) | -- |

| Yes | 2 | (5) | 100% (34–100) | 44 | (53) | 100% (92–100) |

| Family history of gestational diabetes | ||||||

| No | 72 | (88) | 94% (87–98) | 79 | (95) | 100% (95–100) |

| Yes | 10 | (12) | 100% (72–100) | 4 | (5) | 100% (51–100) |

| Family history of diabetes | ||||||

| No | 47 | (57) | 96% (86–99) | 59 | (71) | 100% (94–100) |

| Yes | 35 | (43) | 94% (81–98) | 24 | (29) | 100% (86–100) |

| Schooling | ||||||

| High school or less | 26 | (32) | 96% (81–99) | 26 | (31) | 100% (87–100) |

| Some college or Associate degree | 34 | (41) | 94% (81–98) | 25 | (30) | 100% (87–100) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 22 | (27) | 95% (78–99) | 32 | (39) | 100% (89–100) |

| Married or living with partner | ||||||

| No | 11 | (13) | 91% (62–98) | 16 | (19) | 100% (81–100) |

| Yes | 71 | (87) | 96% (88–99) | 67 | (81) | 100% (95–100) |

| Full-time job or student | ||||||

| No | 27 | (33) | 93% (77–98) | 22 | (27) | 100% (85–100) |

| Yes | 55 | (67) | 96% (88–99) | 61 | (73) | 100% (94–100) |

| Glucose challenge test performed | ||||||

| No | 4 | (5) | 100% (51–100) | 2 | (2) | 100% (34–100) |

| Yes | 78 | (95) | 95% (88–98) | 81 | (98) | 100% (95–100) |

| Oral glucose tolerance test performed | ||||||

| No | 10 | (12) | 100% (72–100) | 67 | (81) | 100% (95–100) |

| Yes | 72 | (88) | 94% (87–98) | 16 | (19) | 100% (81–100) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

Gestational diabetes status determined based on medical record review of oral glucose tolerance test results and discharge diagnosis.

Sensitivity determined as the proportion of women who reported having gestational diabetes postpartum among women with gestational diabetes according to the medical record.

Specificity determined as the proportion of women who did not report having gestational diabetes among the women who did not have gestational diabetes according to the medical record.

Among women who correctly self-reported gestational diabetes diagnosis (n=78), treatment recorded on the medical record was indicated to be by diet only (n=42; 54%) for a majority, while a smaller proportion had treatment with medication (n=33; 42%); treatment was not recorded on the medical record for 3 women (4%). All 42 women with diet-treated gestational diabetes correctly self-reported postpartum that they were treated via diet and lifestyle modification. Most of the 33 women whose medical record indicated that they had medication treated gestational diabetes (n=28; 85%) self-reported that they had treatment with medication; 22 women (67%) also reported having diet and lifestyle modification; however, this was not unexpected as women could select all treatment methods that applied and lifestyle modification may precede or accompany medication treatment.

Medical record glucose challenge test results were available for 159 of the 165 women (78 and 81 women with and without gestational diabetes, respectively). At the postpartum visit, 10 of 159 (6%) women reported that they did not have a glucose challenge test during pregnancy and 65 of 159 (41%) women reported that they did not know their test results and did not attempt to recall their results. Rates for this reporting attempt did not vary between women with (56%) or without (49%) gestational diabetes. Women’s attempt to report their glucose challenge test values varied by race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic whites: 74%; non-Hispanic blacks: 87%; Hispanics: 29%; Asian/Pacific Islanders: 47%), years of schooling (high school or less: 38%; some college or Associate’s degree: 57%; Bachelor’s degree or higher: 63%), and family history of diabetes (yes: 40%; no: 60%).

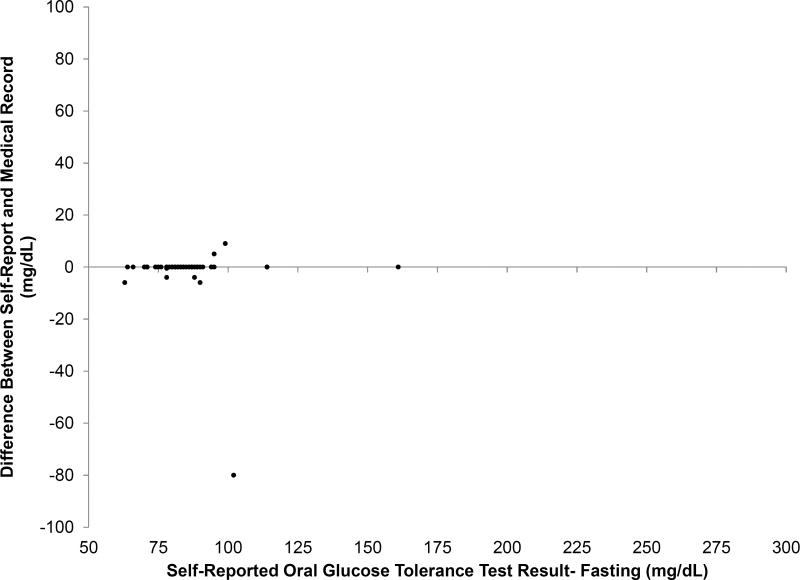

Concordance between self-report and medical records was very high for the glucose challenge test (r=0.97) and oral glucose tolerance test results (fasting, r=0.82; 1-hour, r=0.83; 2-hour, r=0.98; 3-hour, r=0.96); the median difference was 0 mg/dl (interquartile range 0, 0) for all measures. However, there were a small number that were highly discrepant as shown in the Figure and the eFigure. No substantial differences were observed in the accuracy of self-reported glucose results by gestational diabetes status or race/ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Validity of self-reported glucose levels from the glucose challenge test and oral glucose tolerance test recalled at 6-weeks postpartum compared to the medical record. Glucose challenge test results (Figure part A; n = 84); Oral glucose tolerance test results, fasting status (Figure part B; n = 51). X-axis represents the self-reported values. Y-axis represents the difference in glucose levels self-reported at 6-weeks postpartum compared to the medical record. Women who did not attempt to recall their values are not included in the plot.

Sensitivity analyses of women with gestational diabetes reported on the discharge diagnoses, regardless of oral glucose tolerance test results (n=99), and their matched non-gestational diabetes controls (n=104) produced comparable results with sensitivity and specificity of 98% (95% CI 93–99) and 98% (95% CI 93–99), respectively.

Discussion

Findings from this prospective study suggest high validity of self-reported gestational diabetes diagnosis reported at 6 weeks postpartum. Our data indicate that the almost half of the women, regardless of their gestational diabetes status, were unable to recall their specific glucose values from their screening and diagnosis tests. However, if they attempted to recall, their reported values were highly accurate. Notably, gestational diabetes treatment was reported with high accuracy.

Large epidemiologic studies often rely on self-reported gestational diabetes diagnosis as it is difficult to obtain medical records for all participants. In lieu of our findings, previous data from predominately white, educated women from the Nurses’ Health Study II suggested good sensitivity for gestational diabetes reporting with physician confirmation in 94% of women.5 Recent validation data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System suggested that gestational diabetes may be overestimated compared to the medical record.10 Specifically, in New York City and Vermont the sensitivity of self-reported gestational diabetes on the survey was 88% and 82%, respectively. The authors speculated that the two-stage approach to gestational diabetes diagnosis may explain the high degree of over-reporting as women may be confused by a positive glucose challenge test, but negative oral glucose tolerance test. Interestingly, in our study none of the women without gestational diabetes reported having the disease and this was true even for women who had a positive glucose challenge test and subsequently had a negative oral glucose tolerance test. The lower degree of accuracy of gestational diabetes reporting in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System may be due to the later timing of the survey completion, at 4 months postpartum compared to 6 weeks postpartum in our study.

Emerging epidemiologic evidence reveals that maternal glycemia during pregnancy may be associated with offspring adiposity in a dose–response manner,11, 12 which suggests that information on specific glucose concentrations during pregnancy is useful in epidemiologic studies. Unfortunately, data from our study suggest that approximately half of the women could not recall their glucose concentrations in pregnancy, although the accuracy was high if they could recall. As such, postpartum self-report is likely not an optimal source for more specific data on glucose levels in epidemiologic studies. Notably, our findings suggest that gestational diabetes treatment, particularly medication use, was reported with high accuracy and could be used as a proxy for disease severity. In addition, findings from this study may be informative for research studies performing sensitivity analyses needing additional information to complete quantitative bias analyses.

Our findings also have clinical relevance. Postpartum screening is important for identification of type 2 diabetes among high risk women with a history of gestational diabetes. Our data suggest that physicians may be able to rely on a woman’s report of gestational diabetes at her 6 week postpartum appointment to identify women who may require follow-up screening for type 2 diabetes.

Strengths of this study include its diverse sample from 12 U.S. sites and a gold standard based on medical record hospital discharge diagnoses in combination with oral glucose tolerance test results. However, generalizability may be impacted by the fact that these women took part in a rather intensive study with repeated pregnancy visits; these women could be better reporters of their gestational diabetes status than the general public. Also, while the sample included a diverse group of women with respect to race-ethnicity and socio-economic status, inferences within these groups were limited due to the small sample size. Finally, it is possible that there were missed cases of gestational diabetes, but we believe this would be very small. In addition, the chart abstraction was completed by trained staff.

In conclusion, findings from this diverse sample indicate that self-reported gestational diabetes diagnosis and treatment at 6 weeks postpartum was a reliable source of women’s gestational diabetes status in their most recent pregnancy. Thus, ascertaining gestational diabetes status postpartum may be a good option for epidemiologic studies when medical records are unavailable or too costly to obtain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH Library Writing Center for reviewing the manuscript.

SOURCES OF FUNDING: The results reported herein correspond to specific aims of contracts HHSN275200800013C; HHSN275200800002I; HHSN27500006; HHSN275200800003IC; HHSN275200800014C; HHSN275200800012C; HHSN275200800028C; HHSN275201000009C supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health and also including funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have no conflict of interest.

DATA SHARING: Code for replication of the present analyses is available from the corresponding author on request. Requests for data can be made through the NICHD/DIPHR Biospecimen Repository Access and Data Sharing (BRADS) website: https://brads.nichd.nih.gov/.

References

- 1.DeSisto CL, Kim SY, Sharma AJ. Prevalence estimates of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2007–2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E104. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Y, Zhang C. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and Risk of Progression to Type 2 Diabetes: a Global Perspective. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16(1):7. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0699-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaacks LM, Barr DB, Sundaram R, Maisog JM, Zhang C, Louis GMB. Pre-pregnancy maternal exposure to polybrominated and polychlorinated biphenyls and gestational diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Environmental Health. 2016;15(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis JN, Koleilat M, Shearrer GE, Whaley SE. Association of infant feeding and dietary intake on obesity prevalence in low-income toddlers. Obesity. 2014;22(4):1103–1111. doi: 10.1002/oby.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon CG, Willett WC, Rich-Edwards J, Hunter DJ, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE. Variability in diagnostic evaluation and criteria for gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(1):12–16. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosler AS, Nayak SG, Radigan AM. Agreement between self-report and birth certificate for gestational diabetes mellitus: New York State PRAMS. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(5):786–789. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, Trimble ER, Chaovarindr U, Coustan DR, Hadden DR, McCance DR, Hod M, McIntyre HD, Oats JJ, Persson B, Rogers MS, Sacks DA. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1991–2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buck Louis GM, Grewal J, Albert PS, Sciscione A, Wing DA, Grobman WA, Newman RB, Wapner R, D'Alton ME, Skupski D, Nageotte MP, Ranzini AC, Owen J, Chien EK, Craigo S, Hediger ML, Kim S, Zhang C, Grantz KL. Racial/ethnic standards for fetal growth: the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):449 e1–449 e41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of O, Gynecologists Committee on Practice B-O. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 30, September 2001 (replaces Technical Bulletin Number 200, December 1994). Gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(3):525–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietz P, Bombard J, Mulready-Ward C, Gauthier J, Sackoff J, Brozicevic P, Gambatese M, Nyland-Funke M, England L, Harrison L. Validation of self-reported maternal and infant health indicators in the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(10):2489–2498. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1487-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu Y, Olsen SF, Mendola P, Yeung EH, Vaag A, Bowers K, Liu A, Bao W, Li S, Madsen C. Growth and obesity through the first 7 y of life in association with levels of maternal glycemia during pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(3):794–800. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.121780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study: associations with neonatal anthropometrics. Diabetes. 2009;58(2):453–9. doi: 10.2337/db08-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.