Abstract

Heretofore, transgenesis in the parasitic nematode genus Strongyloides has relied on microinjecting transgene constructs into gonadal syncytia of free-living females. We now report transgenesis in Strongyloides stercoralis by microinjecting constructs into the syncytial testes of free-living males. Crosses of individual males microinjected with a construct encoding GFP with cohorts of 12 non-injected females produced a mean of 7.28 ± 2.09 transgenic progeny. Progeny of males and females microinjected with distinct reporter constructs comprised 2.6% ± 0.7% of individuals expressing both paternal and maternal transgenes. Implications of this finding for deployment of CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis in Strongyloides spp. are discussed.

Keywords: Strongyloides, Transgenesis, Male, Microinjection, CRISPR/Cas9

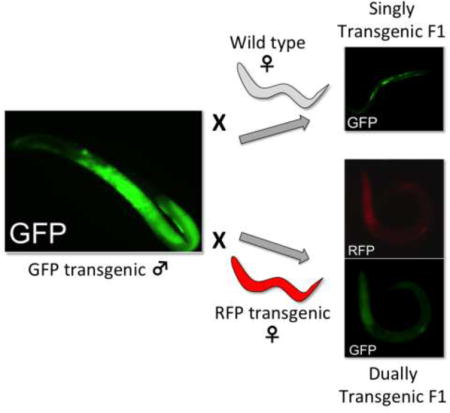

Graphical abstract

Transfer of plasmid-encoded transgenes by microinjection into the syncytial gonads of phenotypically female hermaphrodites became the primary means of gene transfer in the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans when this method was pioneered in the 1980s (Kimble et al., 1982; Stinchcomb et al., 1985; Fire, 1986), and it has remained so to date. Infusing solutions of plasmid-based vectors into the gonadal syncytium results in transformation of a substantial proportion of oocyte nuclei, with the majority of plasmid-encoded transgenes being incorporated into tandem multi-copy arrays that are transmitted as episomes in the F1 generation of progeny and beyond (Mello and Fire, 1995; Evans, 2006). To our knowledge there has been no focused effort to introduce transgenes into C. elegans via the male germline.

Heritable transgenesis in animal parasitic nematodes was first achieved in Strongyloides stercoralis and Parastrongyloides trichosuri (Grant et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006). In contrast to the majority of other animal parasitic nematodes whose adult stages are confined to the definitive host, Strongyloides spp. and related genera have one or more generations of free-living males and females that exchange genetic material during sexual crosses (Viney and Lok, 2015). The body plans of free-living strongyloidoid females are strikingly similar to those of C. elegans hermaphrodites (Lints and Hall, 2009) with amphidelphic ovaries that have syncytial zones in their distal ends (Schad, 1989; Kulkarni et al., 2016), and this has permitted adaptation of microinjection techniques for gene transfer in C. elegans to strongyloidoid parasites with few modifications (Lok and Massey, 2002; Grant et al., 2006; Lok, 2006, 2012; Lok et al., 2016). The result has been a reliable system for introducing transgenes via the female germlines of S. stercoralis (Li et al., 2006; Junio et al., 2008) and Strongyloides ratti (Li et al., 2011) that are expressed in a promoter-regulated fashion in F1 progeny, and ultimately may be integrated into the chromosomes of S. ratti and inherited and expressed indefinitely through host and culture passage (Shao et al., 2012).

We recently used this system for transgenesis in S. stercoralis to express the Cas9 endonuclease and appropriate small guide RNAs to create a precise CRISPR-induced insertional mutation designed to disrupt a selected target gene, Ss-daf-16 (Lok et al., 2016). Given that these CRISPR/Cas9 elements were expressed in pre-fertilization oocytes, we consider it likely that the mutations we confirmed in the F1 progeny derived from these were heterozygous. Using this approach for introducing CRISPR/Cas9 elements into S. stercoralis, creating homozygous mutations would require rearing F1 progeny to infective L3s, infecting a susceptible host to create a patent infection with parthenogenetic parasitic females, collecting their progeny from host feces and engineering crosses between heterozygous free-living males and females in culture to obtain a proportion of homozygous third generation mutants. While theoretically possible, this approach would be difficult to impractical, considering the small numbers of F1 mutant worms that can be produced in a short timeframe and the lack of a well-adapted small animal host for S. stercoralis. We therefore sought a method of generating Strongyloides spp. with disrupting mutations in both alleles of the target gene in a single generation after delivery of transgenes encoding the CRISPR/Cas9 elements. We reasoned that if the targeted heterozygous mutations could be created in germ cells of both male and female parents, then their F1 progeny should contain a proportion of worms that are trans-heterozygous for the two mutant alleles. We would expect such trans-heterozygous worms to be phenotypically mutant and therefore useful for genetic analysis. To this end, we investigated the possibility of introducing transgenes via the male germline of S. stercoralis using microinjection of the distal testis as the method of DNA transfer.

The UPD strain of S. stercoralis, originally isolated from naturally infected dogs in 1976 (Schad et al., 1984), was used for all experiments. This strain was maintained in immunosuppressed dogs and free-living adults were reared and isolated as previously described (Schad et al., 1984; Lok, 2006). Dogs used to maintain S. stercoralis were purpose-bred, mixed breed animals that were handled according to protocols 804798 and 804883 approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), USA. All IACUC protocols, as well as routine husbandry care of the animals, were conducted in strict accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” of the National Institutes of Health, USA.

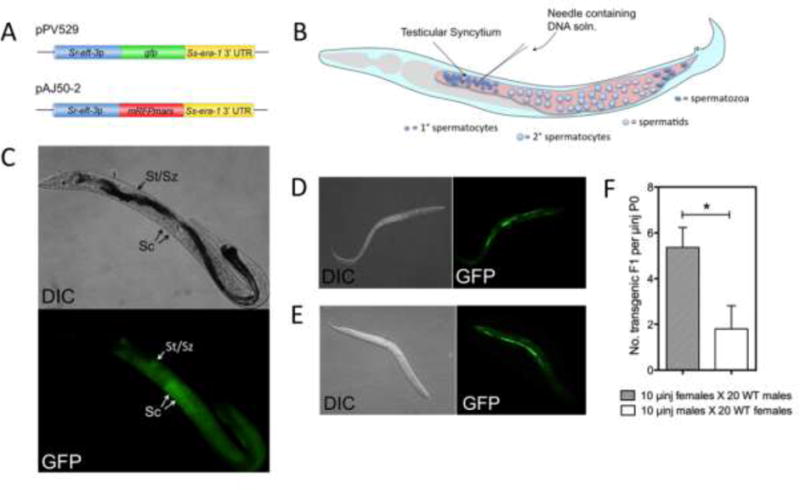

Two transgene constructs, pPV529 and pAJ50-2 (Fig. 1A), were designed to express the GFP and a red fluorescent protein (mRFPmars), respectively, under the promoter for Sr-eft-3 in S. ratti. Just as regulatory sequences from S. stercoralis give active transgene expression in S. ratti (Li et al., 2011), the Sr-eft-3 promoter drives a high level of reporter expression in S. stercoralis from transgenes delivered via the female germline (Fig. 1E). Cloning steps in the preparation of these constructs appear in the legend to Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Transgene constructs microinjected into the free-living male germline of stercoralis are incorporated into sperm and transmitted to F1 progeny following mating with non-transgenic free-living females. (A) Transgene constructs pPV529 and pAJ50-2 encoding GFP and mRFPmars, respectively. Construct pPV529 (GenBank Accession number KY852488) was prepared by digesting pPV254 (GenBank Accession number JX013636) with HindIII and AgeI to excise the Ss-act-2 promoter. The digest was then ligated with a 1163 bp fragment generated from the Sr-eft-3 promoter region in Strongyloides ratti by PCR cloning. Construct pAJ50-2 (GenBank Accession number KY852489) was prepared by digesting the mRFPmars expression vector pAJ50 with HindIII and AgeI to excise the 1295 bp Ss-act-2 promoter fragment. The pAJ50 vector backbone was then re-ligated with the Sr-eft-3 promoter fragment to yield pAJ50-2. In preparing both vectors, restriction digested fragments were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified from gel bands with the MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, USA, Cat. No. 28604). (B) Schematic of the male gonad of S. stercoralis, depicting the point of microinjection into the syncytial testis. (C) Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence (GFP) images of a parental male expressing pPV529 throughout the gonad and in spermatocytes (Sc) in the distal testes and spermatids or spermatozoa (St/Sz) in the proximal testes. (D) DIC and GFP images of a transgenic F1 larva produced by mating microinjected males with wild-type (WT) females. (E) DIC and GFP images of a transgenic F1 larva produced by mating microinjected females with WT males. (F) Relative efficiencies of transgenesis deriving from microinjection (μinj) of 10 parental (P0) females or 10 parental males. Data are means, and error bars represent S.E.M. for three biological replicates; statistical probabilities derived by Student’s T-test. * P ≤ 0.05. soln, solution; UTR, untranslated region.

Free-living male S. stercoralis were immobilized on dry agarose pads on 25 × 50 mm coverslips overlain with paraffin oil and were observed using an inverted microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics at 400× magnification. Vector plasmids were microinjected into the testicular syncytium, which is located in the distal gonad just posterior to the junction between pharynx and intestine (Fig. 1B), using finely drawn glass capillary tubing pressurized with nitrogen and positioned with a micromanipulator. Microinjected males were demounted immediately by gentle prodding with a 36 gauge platinum “worm pick” and transferred to standard 60 mm Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) plates with lawns of Escherichia coli OP50 (Stiernagle, 2006). Bacterial lawns were confined to a central spot approximately 1 cm in diameter in the center of each plate to facilitate mating and assessment of reporter transgene expression in F1 progeny as described below. Transgene constructs were delivered to free-living female S. stercoralis by microinjection into the ovarian syncytium using techniques adapted from C. elegans methodology (Mello and Fire, 1995; Evans, 2006) as previously described (Lok and Massey, 2002; Li et al., 2006). Wild-type and microinjected free-living females were cultured on NGM plates with E. coli OP50 lawns as described for free-living males.

Wild-type free-living female worms were transferred to NGM OP50 plates containing microinjected male worms immediately after microinjections were completed. Plates were then incubated at 22° C for oviposition and hatching of F1 larvae. Plates were observed daily, and final counts of transgenic progeny were made 72 h following microinjection. Cohort sizes of wild-type females varied from 10–120 according to the specific experimental design. In experiments where wild-type free-living males were crossed with microinjected free-living females, female worms were microinjected first and transferred to NGM OP50 plates, then wild-type males were added at a density of two males for each female. In experiments involving crosses between microinjected males and microinjected females, male worms were microinjected first and transferred to plates, followed by an equal number of microinjected females.

Studies on the effects of parental age on efficiency of transgenesis via the male germline involved producing free-living adults of different physiological ages. Growing degree-days (GDD) provide a convention for quantifying development and aging in poikilothermic animals and plants (Genchi et al., 2009). In general, for laboratory studies with constant rearing temperatures, we calculate GDD as:

where the developmental threshold temperature is that below which development ceases. Based on the relationship between temperature and free-living larval development in S. ratti (Sakamoto and Uga, 2013), our GDD calculations assumed a developmental threshold of 12° C for post-parasitic larvae of S. stercoralis. Protocols for rearing S. stercoralis aged 13 and 20 GDD are detailed in the legend of Fig. 2.

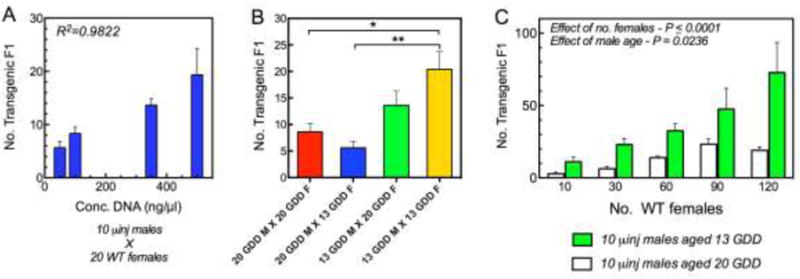

Fig. 2.

Efficiency of transgenesis via the male germline in Strongyloides stercoralis increases with vector DNA concentration, declines with advancing physiological age of the microinjected parental worms and increases with the ratio of wild-type parental females to microinjected parental males in the cross. (A) Effect of increasing construct DNA concentration on the number of transgenic F1 larvae produced by 10 microinjected (μinj) males mated with 20 wild-type (WT) females. R2 = Correlation Coefficient. (B) Transformation efficiency as reflected by the number of transgenic progeny produced by crossing 10 microinjected males (M) and 10 wild-type females (F) aged 13 or 20 growing degree days (GDD). Data are means, and error bars represent S.E.M. for three biological replicates; statistical probabilities derived by one-way ANOVA with post hoc comparisions by the Bonferroni Multiple Comparison Test. * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01. (C) Output of transgenic F1 progeny by a standard cohort of microinjected Strongyloides stercoralis males increases in proportion to the number of wild-type females with which they are mated. Number of GFP-positive progeny produced by 10 microinjected free-living males as a function of increasing numbers of wild-type female parents. Trends for males aged 13 and 20 GDD underscore the advantage of microinjecting younger males. Worms aged 13 GDD were reared from post-parasitic L1s for 24 h at 25° C in charcoal coproculture. Worms aged 20 GDD were reared from L1s in charcoal coproculture for 48 h at 22° C. Data are means and S.E.M. for three biological replicates; statistical probabilities (P) for effects of female number and male age were derived by two-way ANOVA.

F1 larvae were screened for reporter transgene expression based on GFP or mRFPmars fluorescence, examined in detail and imaged as previously described (Stoltzfus et al., 2012). Images were processed with the GIMP software suite (ver. 2.8, www.gimp.org), and algorithms to adjust brightness and contrast were applied in a linear fashion over the entire image.

All experiments were conducted with at least three biological replicates comprising independent parasite isolations and microinjections. Proportional data were normalized using algorithms in Prism version 5.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc., http://www.graphpad.com/) prior to analysis by the parametric methods specified for datasets in the legends of Figs. 1–3. Exact statistical probabilities (P) were calculated for all tests. The criterion for statistical significance was P ≤ 0.05. Data were plotted as means ± S.E.M., and all statistical tests were performed in Prism version 5.03.

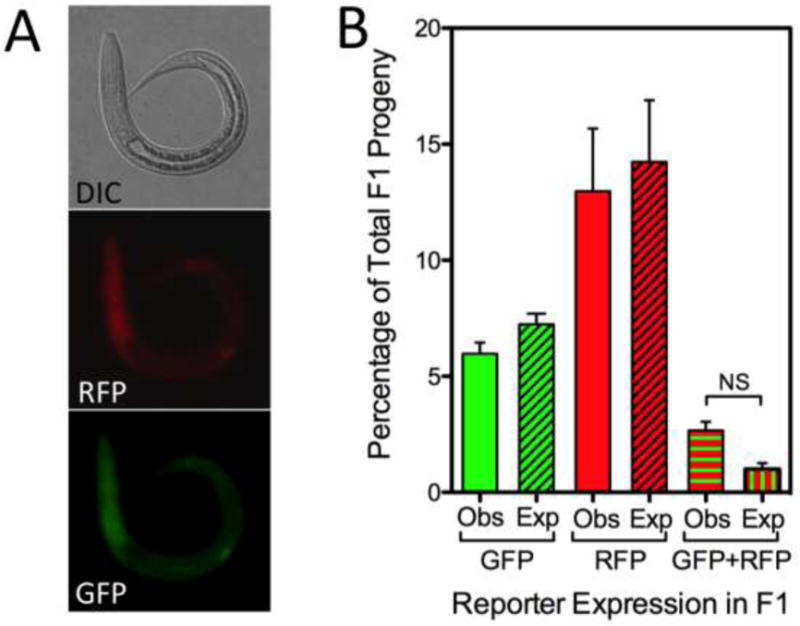

Fig. 3.

Mating of parental free-living males and free-living females microinjected with constructs encoding green and red fluorescent proteins, respectively, produces F1 progeny expressing both reporters. Results of a cross between 20 free-living males microinjected with pPV529 encoding GFP and 20 free-living females microinjected with pAJ50-2 encoding mRFPmars. (A) Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence images of a representative F1 transgenic larva expressing both mRFPmars from the female parent (RFP) and GFP inherited from the male parent (GFP). (B) Observed (Obs) and expected (Exp) proportions of total F1 progeny expressing single GFP or RFP markers or both markers simultaneously (GFP+RFP). Expected proportions were calculated by the following formulae, where p = the proportion of larvae inheriting the GFP reporter transgene from the microinjected male parent, and q = the proportion of F1 larvae inheriting the mRFPmars reporter from the microinjected female parent: p-pq = expected proportion of F1 larvae expressing only GFP; q-pq = expected proportion of F1 expressing only mRFPmars, and pq = expected proportion of F1 larvae expressing both reporters. Data are means of normalized proportions, and error bars represent S.E.M. for three biological replicates. Statistical probabilities were derived from normalized proportions via one-way ANOVA with post-hoc comparisons by the Bonferroni Multiple Comparison Test. No significant differences were detected in any comparison. Lack of significance (NS) is confirmed for the comparison of observed and expected proportions of worms inheriting transgenes from both male and female parents.

Parental male S. stercoralis microinjected into the testicular syncytium with the GFP encoding construct pPV529 at 500 ng/μl exhibited strong green fluorescence throughout the testis 24 h following injection (Fig. 1C). Notably, close inspection of the testis of these microinjected males revealed GFP-expressing spermatogenic stages, identified as spermatocytes based on their large diameter, in the distal gonad and more compact stages identified as spermatids and spermatozoa in the proximal gonad (Fig. 1C). When cohorts of 10 of these microinjected males were mated with 20 wild-type free-living females, F1 progeny included a proportion of larvae expressing GFP (Fig. 1D) in an anatomical pattern identical to that seen in transgenic F1 progeny derived by microinjecting free-living female S. stercoralis with pPV529 and crossing these with wild-type free-living males (Fig. 1E). To our knowledge, this represents the first instance of transgenesis in a nematode by specifically targeting the male germline for gene transfer. This finding also confirms that mating between free-living male and female S. stercoralis involves transmission of genetic traits from both parents to progeny, earlier hypotheses to the contrary notwithstanding (Hammond and Robinson, 1994). In general, efficiency of transgenesis, as reflected in the total number of transgenic F1 larvae per microinjected parent, was significantly higher when female parents were microinjected than when parental males were (Fig. 1F). The relatively low efficiency of transgenesis via the male germline in the initial study prompted us to examine technical factors including the concentration of construct DNA injected, the physiological age of both male and female parents, and the ratio of wild-type females to microinjected males in crosses, that might improve upon this result. There was a significant positive correlation (R2=0.98) between the concentration of construct DNA microinjected into parental males and the production of transgenic F1 larvae produced by a cross between 10 such microinjected males and 20 wild-type females. Numbers of transgenic F1 produced from this cross increased with DNA concentration in the range of 50–500 ng/μl (Fig. 2A). This effect did not reach a maximum in this range, but it was not practical to increase the concentration of construct DNA further because viscosity of more concentrated solutions interfered with their microinjection into the testicular syncytium of male S. stercoralis.

With regard to the optimum physiological age of microinjected males and free-living females in crosses, our standard procedure for transgene delivery via parental free-living female S. stercoralis calls for microinjecting worms reared from post-parasitic L1s in charcoal coprocultures incubated for 48 h at 22° C. Assuming a 12° C temperature threshold for development of post-parasitic S. stercoralis larvae (Sakamoto and Uga, 2013), this protocol would yield worms aged 20 GDD. On this basis, we asked whether a higher efficiency of transgenesis via the male germline could be achieved by microinjecting physiologically younger males and/or by mating the microinjected males with younger females. Using a standard cross of 10 microinjected free-living males with 10 wild-type free-living females, we found that when we used a cross involving both males and females aged 20 GDD as a basis for comparison, no significant increase in efficiency of transgenesis resulted when younger females, aged 13 GDD, were substituted in the cross (Fig. 2B). Similarly, no significant increase in efficiency resulted when younger microinjected males, aged 13 GDD, were mated with older wild-type females. By contrast, a significantly higher efficiency of transgenesis (P ≤ 0.05) was achieved when younger microinjected males were crossed with younger wild-type females (Fig. 2B).

While increasing the concentration of microinjected construct DNA and using physiologically younger microinjected males and wild-type females in crosses modestly enhanced efficiency of transgenesis via the male germline, we achieved a far more significant enhancement by increasing the ratio of wild-type females to microinjected males in the crosses of parental worms. We had observed that free-living S. stercoralis males mate with numerous different free-living females when cultured together on agar plates. We reasoned therefore, that we might increase the output of transgenic F1 larvae produced by the microinjected males simply by providing larger cohorts of wild-type females to them in the crosses established after microinjection. To test this, we examined the relationship between the number of transgenic F1 progeny produced by 10 microinjected males (aged 13 or 20 GDD) and the size of the wild-type female cohort used in the cross. A highly significant (P ≤ 0.0001) increasing trend in the output of F1 progeny resulted from increasing wild-type female numbers in the range of 10–120 (Fig. 2C). This trend was significantly more pronounced (P = 0.0236) with males aged 13 GDD than with males aged 20 GDD. Overall, the output of transgenic larvae from the cross between 10 microinjected males aged 13 GDD and 120 wild-type females (7.2 transgenic F1s per microinjected male; Fig. 2C) exceeded the output of transgenic F1s produced by more conventional crosses of 10 microinjected females with 20 wild-type males (5.4 transgenic F1s per microinjected female; Fig. 1F). Therefore, we can easily offset the intrinsically lower efficiency of trangenesis via the male germline in S. stercoralis (Fig. 1F) by making the female-to-male ratio in crosses 12:1 or greater (Fig. 3). Indeed, our experiments in this vein did not identify a maximal effect, and so it is possible that we could further increase the yield of transgenic F1 progeny from a given cohort of microinjected males by providing even larger cohorts of wild-type free-living females for mating. This would amount to a significant advance in transformation technology for Strongyloides spp. since the chief bottleneck in establishing stable transgenic lines is amassing a sufficient number of transformed infective larvae in the F1 generation to establish a patent infection in the first host passage (Shao et al., 2012). The potential to amass large numbers of F1 transgenics by gene transfer into free-living males would facilitate establishing stable lines of transgenic S. ratti by passage in its natural rat host and could enable the first transgenic lines of S. stercoralis by passage in the less well-adapted gerbil host (Nolan et al., 1993), which would practically require an inoculum of 500 transgenic F1 infective larvae in order to derive second-generation transformants.

The primary impetus for this study of transgenesis via the male germline in S. stercoralis was the need for a method to produce parasites with CRISPR/Cas9 mutations in both alleles of the target gene in a single generation. We reasoned that this could be accomplished by simultaneously delivering transgene-encoded CRISPR/Cas9 elements into the germlines of both free-living male and female parents, thereby deriving a proportion of trans-heterozygous mutants among their F1 progeny. To ascertain the feasibility of this approach, we microinjected 20 free-living male S. stercoralis with the GFP-encoding construct pPV529 and 20 free-living females with the mRFPmars-encoding construct pAJ50-2. All parental worms were aged 13 GDD. Transgenic F1 progeny from crosses between these parents comprised a majority of worms singly transformed with either pAJ50-2 or pPV529 and a minority of worms expressing both the paternal and maternal transgenes (Fig. 3A). These dually transformed progeny constituted a mean of 2.58% of 309 total progeny observed in three biological replicates of the experiment (Fig. 3B). Observed proportions of singly and dually transformed F1 larvae resulting from these crosses did not differ significantly from expected values calculated based on the frequencies of singly transformed F1 larvae resulting from microinjecting the appropriate constructs into the male or female parent only. Thus, it is possible to derive a post free-living generation of S. stercoralis containing larvae that have inherited transgenes from both their male and female parents. In addition to its potential to enhance methods for transgenesis in Strongyloides overall, male-directed gene transfer also represents a possible means of generating parasites with CRISPR/Cas9 mutations in both alleles of a target gene by methods now under development (Lok et al., 2016). Effecting CRISPR/Cas9 mutations in a target gene within germ cells of both male and female parents and crossing these individuals should result in F1 progeny that comprise up to 25% trans-heterozygous individuals, which would be phenotypically mutant. This would be accomplished in a single free-living generation, encompassing 72–96 h, without the use of animals for host passage. The trans-heterozygous, phenotypically mutant individuals thus prepared would afford the opportunity to observe phenotypes in pre-parasitic larval stages and possibly in parasitic stages within the host and in subsequent generations. The proportion of dually transformed F1 larvae we produced in this instance was small, but it is noteworthy that this experiment involved mating parental cohorts of 20 microinjected males with 20 microinjected females. We show elsewhere in this study (Fig. 2C) that even a modest increase in the number of microinjected females in this cross could bring about a significant increase in the output of dually transformed F1 larvae, making it feasible to attempt host passage of these mutant progeny to establish stable lines, especially if the well adapted S. ratti/rat system is used as we have done previously (Shao et al., 2012).

Highlights.

Strongyloides sperm are transformed by injecting DNA into the free-living male testes.

Transformed males transmit transgenes to progeny by mating with wild-type females.

Transgene propagation is enhanced by multiple matings of transgenic males.

Progeny of transformed males and females inherit transgenes from both parents.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (grants AI50688, AI105856 and NIH OD P40-10939). We thank Tegegn Jaleta, Gongyi Ren, Nicole Bacarella, Lindsay McMenemy and Erika Klemp for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Evans TC. Transformation and microinjection. In: The C. elegans Research Community, editor. WormBook. WormBook; 2006. http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A. Integrative transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. Embo J. 1986;5:2673–2680. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genchi C, Rinaldi L, Mortarino M, Genchi M, Cringoli G. Climate and Dirofilaria infection in Europe. Vet Parasitol. 2009;163:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant WN, Skinner SJ, Newton-Howes J, Grant K, Shuttleworth G, Heath DD, Shoemaker CB. Heritable transgenesis of Parastrongyloides trichosuri: a nematode parasite of mammals. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond MP, Robinson RD. Chromosome complement, gametogenesis, and development of Strongyloides stercoralis. J Parasitol. 1994;80:689–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junio AB, Li X, Massey HC, Jr, Nolan TJ, Todd Lamitina S, Sundaram MV, Lok JB. Strongyloides stercoralis: cell- and tissue-specific transgene expression and co-transformation with vector constructs incorporating a common multifunctional 3′ UTR. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118:253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble J, Hodgkin J, Smith T, Smith J. Suppression of an amber mutation by microinjection of suppressor tRNA in C. elegans. Nature. 1982;299:456–458. doi: 10.1038/299456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni A, Lightfoot JW, Streit A. Germline organization in Strongyloides nematodes reveals alternative differentiation and regulation mechanisms. Chromosoma. 2016;125:725–745. doi: 10.1007/s00412-015-0562-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Massey HC, Nolan TJ, Schad GA, Kraus K, Sundaram M, Lok JB. Successful transgenesis of the parasitic nematode Strongyloides stercoralis requires endogenous non-coding control elements. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Shao H, Junio A, Nolan TJ, Massey HC, Jr, Pearce EJ, Viney ME, Lok JB. Transgenesis in the parasitic nematode Strongyloides ratti. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2011;179:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lints R, Hall DH. Reproductive system, germ line. WormAtlas. 2009a doi: 10.3908/wormatlas.1.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lok JB. Strongyloides stercoralis: a model for translational research on parasitic nematode biology. In: The C. elegans Research Community, editor. WormBook. WormBook; 2007. http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok JB. Nucleic acid transfection and transgenesis in parasitic nematodes. Parasitology. 2012;139:574–588. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011001387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok JB, Massey HC., Jr Transgene expression in Strongyloides stercoralis following gonadal microinjection of DNA constructs. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;119:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok JB, Shao H, Massey HC, Li X. Transgenesis in Strongyloides and related parasitic nematodes: historical perspectives, current functional genomic applications and progress towards gene disruption and editing. Parasitology. 2017;144:327–342. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C, Fire A. DNA transformation. Meth Cell Biol. 1995;48:451–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan TJ, Megyeri Z, Bhopale VM, Schad GA. Strongyloides stercoralis: the first rodent model for uncomplicated and hyperinfective strongyloidiasis, the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1479–1484. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M, Uga S. Development of free-living stages of Strongyloides ratti under different temperature conditions. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:4009–4013. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schad GA. Morphology and life history of Strongyloides stercoralis. In: Grove DI, editor. Strongyloidiasis: a Major Roundworm Infection of Man. Taylor & Francis Inc; Philadelphia, USA: 1989. pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Schad GA, Hellman ME, Muncey DW. Strongyloides stercoralis: hyperinfection in immunosuppressed dogs. Exp Parasitol. 1984;57:287–296. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(84)90103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H, Li X, Nolan TJ, Massey HC, Jr, Pearce EJ, Lok JB. Transposon-mediated chromosomal integration of transgenes in the parasitic nematode Strongyloides ratti and establishment of stable transgenic lines. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002871. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. In: The C. elegans Research Community, editor. WormBook. WormBook; 2006. http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchcomb DT, Shaw JE, Carr SH, Hirsh D. Extrachromosomal DNA transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3484–3496. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltzfus JD, Massey HC, Jr, Nolan TJ, Griffith SD, Lok JB. Strongyloides stercoralis age-1: a potential regulator of infective larval development in a parasitic nematode. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viney ME, Lok JB. The biology of Strongyloides spp. In: The C. elegans Research Community, editor. WormBook. WormBook; 2015. http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]