Abstract

Objectives

The current psoriatic arthritis (PsA) Core Domain Set defines core domains to be measured in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and longitudinal observational studies (LOS) and was published in 2006. At the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) meeting in 2014, researchers, clinicians and patients unanimously voted for updating the PsA Core Domain Set to include the patient perspective in accordance with OMERACT Filter 2.0. Herein we report the proceedings of the PsA Workshop at the OMERACT meeting in 2016 including studies presented in the plenary, results of breakout group discussions, and final voting and endorsement of the 2016 updated PsA Core Domain Set.

Methods

We conducted research to develop the updated PsA Core Domain Set. At OMERACT 2016 this work was presented, discussed in breakout groups and the updated PsA core domain set was voted on and endorsed by OMERACT participants.

Results

The updated PsA Core Domain Set includes: musculoskeletal disease activity, skin disease activity, fatigue, pain, patient global, physical function, health related quality of life and systemic inflammation which are recommended for all RCTs and LOS). Economic cost, emotional well-being, participation and structural damage are important but not required in all RCTs and LOS. Independence, sleep, stiffness and treatment burden on the research agenda.

Conclusion

The updated PsA Core Domain Set was endorsed at OMERACT 2016. Next steps for the PsA working group include evaluation of available outcome measures for each of the core domains and development of a PsA core outcome measurement set.

Key indexing terms: psoriatic arthritis, core set, outcome measures

INTRODUCTION

STATEMENT OF CONTRIBUTION TO THE LITERATURE: This paper describes the the research work streams that led to the updated PsA Core domain set and its final endorsement at OMERACT 2016. The 2016 updated PsA Core Domain Set will allow the beginning of patient-centered and evidence-based selection of a Core Outcome Measurement set for future PsA clinical trials. This paper uniquely describes the OMERACT 2016 conference process which led to the endorsement of the final updated 2016 PsA Core domain set and has not been submitted elsewhere.

The updated 2016 PsA Core Domain Set contains the following revised or new domains compared to the 2006 core set:

MSK disease activity (revised to include peripheral joints, dactylitis, enthesitis and spine symptoms)

Skin activity (revised to include skin and nails)

Fatigue

Systemic inflammation.

Participation, Emotional well-being, Structural damage and Economic cost are designated important and are not required in all clinical trials.

The purpose of disease core sets is to standardize measurement and reporting of outcomes in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and longitudinal observational studies (LOS). Implementation and reporting of disease core sets in RCTs is key to generating high quality evidence to support useful treatment recommendations (1). Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) pioneered disease core set development and refined their methodology based on evidence (2, 3). In 2014, OMERACT presented and published Filter 2.0 outlining a methodologically rigorous process for defining core domain sets (5) based on early inclusion of the views of key stakeholders, especially patients and iterative, evidence-driven consensus among stakeholders. At the OMERACT 2014 conference, participants recognized the need to update the PsA Core Domain set based on the new OMERACT filter and, integral to this process, to incorporate the voice of patients and rapidly developing scientific knowledge about the disease and the measurement of PsA (6, 7). OMERACT 2014 attendees (including researchers, patient partners and clinicians) voted to update the PsA core domain set (100% voted yes) and additionally voted to include fatigue (72%) and dactylitis (70%) in the core set (8).

Since the OMERACT 2014 meeting, the GRAPPA-OMERACT PsA working group conducted research projects (9) to identify domains important to patients and physicians for the PsA core domain set update. This paper summarizes results presented at the OMERACT 2016 PsA workshop and breakout group discussions and the subsequent endorsement of the updated PsA core domain set.

Summary of research conducted in preparation for OMERACT 2016

The PsA working group conducted the following research projects: 1) a systematic literature review (SLR) in Pubmed and EMBASE to identify domains measured in PsA RCTs, LOS and registries; 2) international focus groups with patients with PsA to identify domains; 3) international patient and physician surveys; and 4) a consensus meeting held March 12, 2016 in Jersey City, NJ, US with patients and physicians using the nominal group technique (NGT) to draft a PsA core domain set. Detailed methods and results are presented in separate manuscripts (9, 10) (reference to be added later).

Studies were approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (IRB), Baltimore, MD, USA (IRB00093948 and NA_00066663), the National Research Ethics Service Committee North West – Haydock, UK (REC reference: 15/NW/0609) and the online survey study was accorded exempt status at the University of Pennsylvania IRB, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

The SLR has been published and showed the measurement of the complete 2006 PsA core domain set increased from being performed in 24% of RCTs (from 2005 to 2010) to 59% of RCTs (from 2010 to 2015) (10, 11). Twenty-four domains were identified from the SLR, with 18 measured in addition to the core set (Figure 1). The changes over time are likely related to dissemination of the PsA core set, recognition of the importance of fatigue, productivity and other aspects of life impact for patients (8, 12–14), and availability of outcome measures for domains such as dactylitis (15).

Figure 1.

Domains are shown on the X axis with proportion of studies measuring each domain on the Y axis. The black mark designates 2006 PsA core domains. RCT: randomized controlled trials; LOS: longitudinal observational studies; HRQL: health-related quality of life; MD: physician; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; US: ultrasound.

Qualitative research was conducted to identify domains directly from patients to include their perspective at the inception of the process (16). Two focus group studies were conducted: one international (16 focus groups with 89 patients in total in Australia, Brazil, France, Netherlands, Singapore and US) and one multicenter study in the UK (8 focus groups with 41 patients). Qualitative data analysis of each study identified patient domains. Across both studies there were 34 unique patient domains.

The 24 domains from the SLR and 34 domains from international focus groups were then combined into a list of 39 unique domains. Patients (n=50) recruited from rheumatology clinics and patient organizations and physicians (n=75) recruited through GRAPPA rated domains via electronic surveys running in parallel. Results were discussed at the NGT consensus meeting held March 12, 2016 with 12 patients and 12 physicians. The NGT method allowed stakeholders to prioritize items ensuring the inclusion of all participants’ opinions (17). At the end of the consensus meeting a draft core domain set was agreed upon and included 10 domains: musculoskeletal (MSK) disease activity (peripheral joints, enthesitis, dactylitis and spine symtoms), skin disease activity (skin and nails), pain, patient global (patient reported disease related health status), physical function, participation, emotional well-being, fatigue, systemic inflammation, structural damage (to be measured at least once during a new drug development program for PsA). A domain considered important but not required in all RCTs and LOS was economic cost (societal financial impact not otherwise captured by participation and work/employment domains). The NGT core domain set was then rated in a second electronic survey completed in parallel by patients and physicians. Based on results from the second round of surveys the draft core domain set included nine domains: MSK disease activity, skin disease activity, pain, patient global, physical function, participation, fatigue, systemic inflammation, structural damage (to be measured at least once during a new drug development program for PsA) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Domains in the 2006 PsA Core Domain Set and candidate domains for the updated core set

| OMERACT 2006 PsA Core Domain Set |

OMERACT 2014 voted (≥70%) inclusion in the core set |

Draft core domain set at the end of the NGT* meeting 2016 |

Draft core set after the 2nd patient and physician survey** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral joint activity | Dactylitis | MSK disease activity | MSK disease activity |

| Skin activity | Skin disease activity | Skin disease activity | |

| Pain | Pain | Pain | |

| Patient global | Patient global | Patient global | |

| Physical function | Physical function | Physical function | |

| HRQoL | |||

| Participation | Participation | ||

| Emotional well-being | |||

| Fatigue | Fatigue | Fatigue | |

| Systemic inflammation | Systemic inflammation | ||

| Structural damage *** | Structural damage *** |

NGT nominal group technique meeting,

during the second survey patients and physicians rated the importance of domains proposed after the NGT meeting – emotional well-being was moved out of the core as less than 70% of either physician or patient respondents rated it as at least 8 on a scale from 0–10,

structural damage was recommended for assessment at least once during the development of a new drug for PsA.

Patients were involved at all levels as research participants, patient researchers (conducting focus groups and analyzing data), or patient research partners (PRPs; assisting in the high level conduct of the research) in each of the work streams (Table 2). One PRP was a member of the steering committee for the working group (reference to be added later).

Table 2.

Patients involved in the PsA Core Domain Set update

| Country | International patient focus group participants |

Qualitative data analysis (patient researchers, PRPs) |

Survey participants | Nominal group technique patient participants and PRPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 7 | |||

| Brazil | 12 | 1 | 1 | |

| Canada | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| France | 12 | 4 | ||

| Hong Kong | 1 | |||

| Ireland | 9 | 1 | ||

| Italy | 1 | |||

| Netherlands | 17 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Norway | 1 | 1 | ||

| Romania | 1 | |||

| Singapore | 13 | 8 | ||

| Spain | 1 | |||

| UK | 41 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| USA | 27 | 1 | 18 | 4 |

| Total | 129 | 6 | 50 | 12 |

Working group meeting at OMERACT 2016

A working group meeting was held at OMERACT prior to the PsA Workshop for final review of the workshop presentation, breakout group organization and voting questions. At this meeting decisions were made regarding the core domain set to be presented at the workshop:

Structural damage was important but not required in all RCTs and LOS. This was congruent with the NGT meeting where structural damage was recommended to be measured once during the development of a new therapeutic agent for PsA but not required in all RCTs.

Health related quality of life (HRQoL) remained a core domain required in all RCTs and LOS based on its presence in the 2006 core domain set.

The group decided to hold two separate votes for participation: first for inclusion in the core domain set (required in all RCTs and LOS) and second (if first not agreed by 70%) for inclusion in the middle circle (important but not required in all RCTs and LOS). Work/employment (included in participation) was rated high in the first survey by both patients and physicians, and participation was in the preliminary core set after the NGT meeting as well as rated high by patients in the second survey. However, due feasibility concerns and overlap of participation with the broader concept of HRQoL, we anticipated both may not be accepted in the core set (and therefore the decision to hold two votes).

Due to the importance of emotional well-being for patients, both in the NGT meeting and also at this working group meeting, the group similarly decided to first vote for inclusion of emotional well-being in the core set and second (if first not agreed by 70%) vote for inclusion in the middle circle.

The group also agreed upon the final list of voting questions for the conclusion of the workshop.

OMERACT 2016 PsA workshop

The PsA workshop began with presentation of results, continued with eight breakout group discussions running in parallel followed by reports from each breakout group, and concluded with voting. Results from research conducted in preparation for OMERACT were presented to workshop participants as above (Table 1).

Breakout group discussions were facilitated by two people (one moderator and one reporter), both of whom were either a member of the working group or experienced PsA or psoriasis researchers. The four PsA working group PRPs were either a group moderator or reporter. All breakout groups discussed each new or updated domain: participation, systemic inflammation, MSK disease activity and skin activity, emotional well-being and structural damage. Fatigue had been voted for inclusion in the core domain set by 72% of the participants at the OMERACT 2014 conference (8) and was not discussed again. For each domain breakout group participants were asked to provide arguments supporting inclusion in the core domain set as well as perceived challenges. Throughout the process of developing the core set and also in the breakout groups, discussion of how to best measure a particular domain was discouraged as instruments were not felt to be relevant at this stage to the decision on which domains to include. A summary of breakout group discussions is presented in supplement Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of core domain discussion during PsA workshop breakout groups at OMERACT 2016

| Domain | Support inclusion | Challenges | Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural damage | Important aspect of medication efficacy for PsA. Keep a special status in the middle core with requirement to be measured at least once during the development program of a new drug for PsA. |

Not feasible to require in all RCTs. Small changes if any (no responsiveness) in short clinical trials. |

Combining modalities of assessment is important. Measurement instruments may concomitantly assess damage, inflammation and disease activity |

| Systemic inflammation | Important, majority in all

groups supported inclusion. Also very important in longitudinal studies due to link with heart disease and potentially other comorbidities. |

- | When considering instruments also consider imaging for this domain |

| Emotional well-being | Very important to patients:

important in qualitative research and patient surveys. Psychological distress is frequent in both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Together with participation and fatigue an appropriate replacement for HRQoL. |

Feasibility concern and concern over necessity in every RCT. Multifactorial concept potentially overlapping with patient global and fatigue. How is it different from HRQoL? This could be an important/key contextual factor. |

We need to better understand overlap with patient global and HRQoL. We also need to find instruments for assessment. Emotional well-being should be examined as a contextual factor. |

| MSK disease activity | Majority agreement with the

updated comprehensive MSK disease activity. Easily comprehensible as a domain even for non- rheumatologists. |

Inclusion of spine symptoms within MSK disease activity is challenging due to the lack of good instruments to assess activity; additionally, measuring spine symptoms in all trials is not currently feasible. Some preferred the individual components be considered instead of the broader domain of MSK disease activity. |

|

| Participation | Face validity: important to

patients and physicians, shows ability to “live one’s life”. A common discussion point was that participation is really at the core of why we treat patients: to improve their function in their daily lives. Participation can be measured and it is responsive. Work and employment are very important for patients. This is distinct from physical function. However, this is also more than just work and includes social and leisure activities. |

The definition as proposed is broad. There was a concern for overlap with HRQoL and physical function, and it may be influenced by emotional well-being. Concern for redundancy if also including HRQoL in inner core. Some thought it should be one or the other. |

Include in the inner core and move HRQoL in the middle circle. Study the independent contribution of the domain in explaining PsA variability; and overlap with other domains. |

| Skin disease activity | Majority agreement, important

to patients and physicians |

Some concerned about feasibility of measuring in all RCTs |

|

| Patient global assessment |

Always measured | Problematic to pinpoint the exact concept behind this domain |

The patient global needs to be addressed among all diseases and should be further studied. |

| Physician global | N/A | Felt to be captured in MSK disease activity. Potentially subject to bias. |

|

| Proposed core set | Felt to be comprehensive. A strength is that most of these domains are already measured in clinical trials. |

Some participants felt the core set contained too many domains, potentially limiting feasibility. There was a concern for responder burden at the measurement stage. |

Examine

PROMIS measures Examine redundancies among domains. |

Following the breakout group reporting in the plenary, OMERACT participants voted for individual domains and this concluded the workshop (Table 4). The only modification to the preliminary core set was movement of participation to the middle circle (important but not required in all RCTs and LOS).

Table 4.

Voting results at the conclusion of the PsA workshop

| Domain | Inner core position | Middle circle position | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes* | Yes (%) | No (%) | Insufficient evidence or information (%) |

Yes (%) | No (%) | Insufficient evidence or information (%) |

| MSK disease activity |

85 | 8 | 7 | - | - | - |

| Skin activity | 91 | 6 | 4 | - | - | - |

| Systemic inflammation |

81 | 14 | 4 | - | - | - |

| Participation | 55 | 32 | 13 | 74 | 19 | 7 |

| Emotional well- being |

31 | 57 | 13 | 77 | 17 | 5 |

| Structural damage | - | - | - | 79 | 15 | 5 |

The number of OMERACT participants who voted for each question ranged from 132 to 138.

OMERACT 2016 Final Plenary

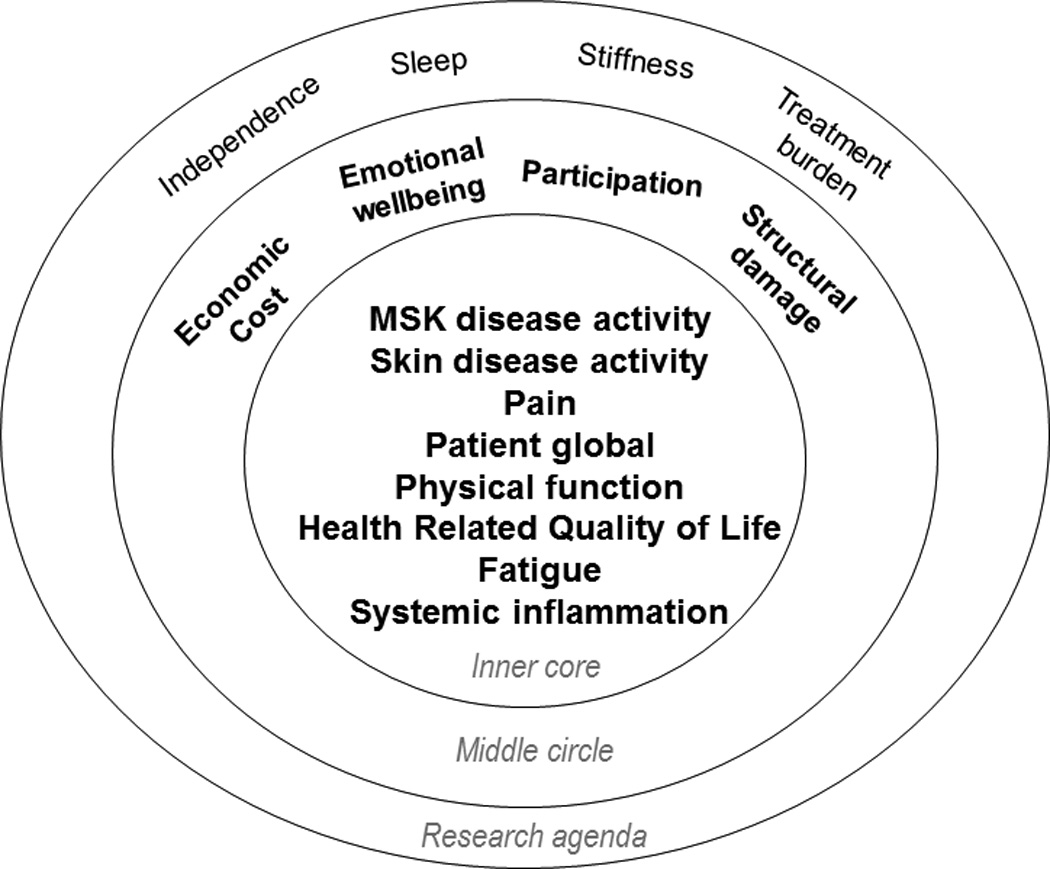

At the OMERACT plenary the final PsA 2016 Core Domain Set was proposed for endorsement and achieved consensus with a 90% vote from 130 participants at the conference. The updated 2016 PsA core domain set includes the following outcomes recommended for assessment in all RCTs and LOS (inner core): MSK disease activity, skin disease activity, fatigue, pain, patient global, physical function, HRQoL and systemic inflammation. The following outcomes (middle circle) are important but not required in all RCTs/LOS: economic cost, emotional well-being, participation and structural damage. Outcomes that need to be studied further due to their importance for people with PsA include: independence, sleep, stiffness and treatment burden (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Updated 2016 PsA Core Domain Set. MSK disease activity includes peripheral joints, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spine symptoms. Skin activity includes skin and nails. PtGA is defined as patient-reported diseaserelated health status. The inner circle includes domains recommended for measurement in every RCT and LOS. The middle circle includes domains that are important, but not required in every RCT and LOS. The outer circle contains domains that may be important, but need further study. PsA: psoriatic arthritis; MSK: musculoskeletal; PtGA: patient’s global assessment; RCT: randomized controlled trial; LOS: longitudinal observational studies. Reproduced with permission from Orbai, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2016 Dec 13(E-pub ahead of print).

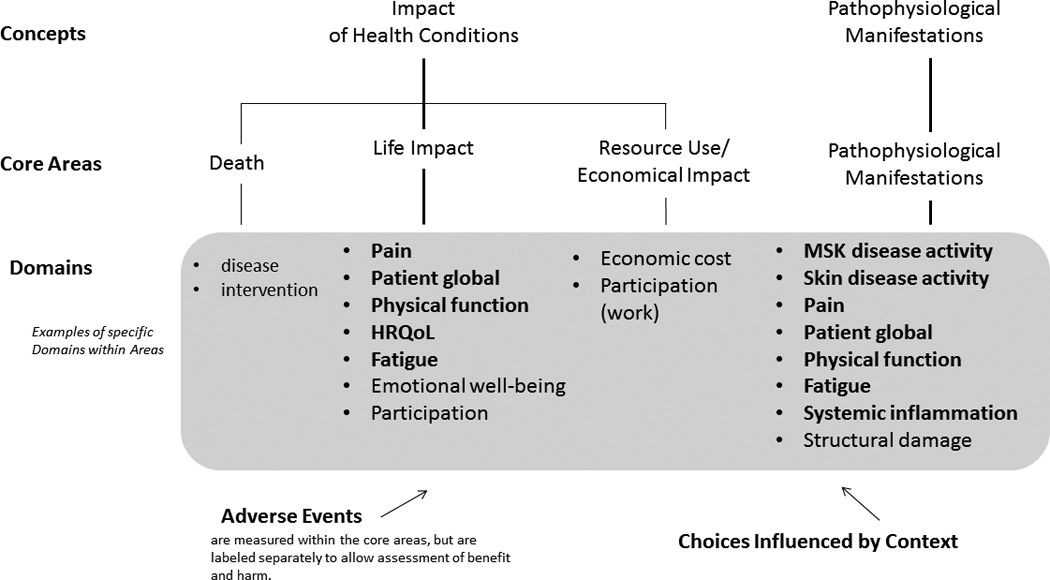

Contextual factors for PsA are another important area that needs further study. Adverse events are measured in every RCT and are part of the OMERACT outcome framework. The updated 2016 PsA Core Domain Set addresses all areas of the OMERACT Filter 2.0 framework (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Updated PsA Core Domain Set and corresponding OMERACT core areas. Domains in bold face are in the core set (to be measured in all RCT), and domains in plain font are in the middle circle (highly recommended, but not mandatory). PsA: psoriatic arthritis; OMERACT: Outcome Measures in Rheumatology; RCT: randomized controlled trial; HRQOL: health-related quality of life; MSK: musculoskeletal. From Boers M, et al. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:745-53; adapted with permission.

DISCUSSION

Psoriatic arthritis is a heterogeneous disease with tremendous impact on patients’ lives. At OMERACT 2014 the GRAPPA-OMERACT PsA working group committed to updating the 2006 PsA Core Domain set to incorporate the input of people living with PsA and advances in the field. Candidate domains for the updated PsA Core Domain Set were obtained directly from patients through international focus groups and an SLR of outcomes measured in PsA RCTs, LOS and registries. During the surveys and consensus meeting with patients and physicians, each domain presented for rating or discussion was accompanied by a clear definition based on focus group patient participants’ descriptions and reviewed by the working group including PRPs. We adopted this method to maximize understanding for all participants and to minimize subjective interpretations during the surveys and the consensus meeting.

The concept of MSK disease activity which encompasses peripheral joints, enthesitis, dactylitis and spine symptoms has been initially suggested in breakout groups at OMERACT 2014 (8) out of concerns for parsimony in the core set. This comprehensive definition for MSK disease activity was fully supported at the consensus meeting with patients and physicians and endorsed with majority vote at OMERACT 2016.

Discussion at OMERACT 2016 focused particularly on the inclusion of participation and emotional well-being. Participation (encompassing work and/or employment within and outside the home, leisure activities, social activities and family roles) was defined congruent with the ICF definition which is “involvement in a life situation” and distinct from activity which implies “the execution of a task or action” (18). Ability to perform work (both paid and unpaid) is an important outcome to patients and ranked highly in surveys with patients conducted by our working group and also in the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) led Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) study (12). Estimates of unemployment and work disability range from 20–50% and 16–39% respectively in clinical trials and cohort studies (19) and appropriate therapy can improve aspects of participation (20). Therefore participation has face validity and optimal measurement needs to be studied further.

Emotional well-being was defined as “feeling good about oneself” and may include additional domains such as depressive mood, anxiety, embarrassment, self-worth, frustration, and stress. During the NGT meeting, emotional well-being was highly relevant to the management of PsA for patient participants. Previous studies suggested 20% of patients with PsA have depression and one study found that 37% had anxiety (21). The best way of measuring emotional well-being in patients with PsA has not been investigated. The PsAID includes items on depression, anxiety and embarrassment and the Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form-36 (SF-36) includes “mental health”, “role emotional”, “vitality” and also “social functioning” domains (22). Following discussions at OMERACT 2016, and in line with the second survey with patients and physicians it became clear that additional research may be needed before emotional well-being might become an inner core element.

An aspect discussed for both participation and emotional well-being was conceptual overlap with HRQoL. Concomitant measurement of all these concepts may be redundant and demanding on responders. Another consideration is that patient participants in focus groups described specific areas of PsA life impact. For this reason, for patients it may be difficult to relate to overarching concepts like HRQoL when considering their treatment options. There was discussion to replace the generic construct of HRQoL with explicit domains that are patient relevant: participation, fatigue and emotional well-being. This is an important area for future research in PsA.

One concern raised at OMERACT 2016 was the number of domains and subdomains mandatory in all future PsA RCTs and LOS. PsA is a highly heterogeneous disease and measuring only one part may be misleading or lead to limited information for patients and clinicians. Importantly, most of these domains are currently being measured in RCTs (9). However, examination for areas of overlap is important to decrease redundancy.

Next steps include investigation of instruments available to measure the Core Domain Set. We are beginning this process with an SLR of instruments for each core domain. We will investigate psychometric properties of available instruments such as face and content validity (including match with the domain of interest) and feasibility as a part of the recently described OMERACT decision making process for selection of outcome measures or “the eyeball test” (23). Focus groups will take into account patient’s impressions of the instruments. We will simultaneously examine instrument construct validity and responsiveness in RCT datasets and LOS currently in progress. These work streams will inform the development of a PsA Core Outcome Measurement set.

Additionally, the research agenda included items of importance to patients: independence, sleep, stiffness and treatment burden. These domains need further study of their contribution to PsA assessment.

In summary, the updated PsA Core Domain set incorporates patient input, scientific knowledge on pathophysiologic manifestations and measurement of disease in PsA, and the broad life impact of PsA. Next steps include development of a PsA Core Outcome Measurement set for RCTs and LOS.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: A-MO was supported in part by a Scientist Development Award from the Rheumatology Research Foundation and the Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center Discovery Fund. AO was supported by research grant K23 AR063764 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. This work was supported in part by research grant P30-AR053503 (RDRCC Human Subjects Research Core) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the Camille J. Morgan Arthritis Research and Education Fund. The international focus group study was supported by research grants from Celgene and Janssen. The nominal group technique meeting was supported by research grants from Abbvie, Celgene and Pfizer. The UK focus group study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (Programme Grants for Applied Research, Early detection to improve outcome in patients with undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis, RP-PG-1212-20007). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. Attendance of working group fellows and patient research partners to the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) conference was supported with workshop funds from Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) and OMERACT.

Contributor Information

Ana-Maria Orbai, Division of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore USA.

Maarten de Wit, VU Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Philip Mease, Rheumatology Research, Swedish Medical Center and University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA.

Kristina Callis Duffin, Department of Dermatology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

Musaab Elmamoun, Dept of Rheumatology, St. Vincents University Hospital and Conway Institute for Biomolecular Research, University College Dublin, Ireland.

William Tillett, Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, UK.

Willemina Campbell, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Oliver FitzGerald, Newman Clinical Research Professor, Dept of Rheumatology, St. Vincents University Hospital and Conway Institute for Biomolecular Research, University College Dublin, Ireland.

Dafna Gladman, Medicine, University of Toronto; Senior Scientist, Krembil Research Institute; Director, Psoriatic Arthritis Program, University Health Network; Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Niti Goel, Quintiles, Duke University School of Medicine. Durham, NC, USA.

Laure Gossec, Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ Paris 06, Institut Pierre Louis d’Epidémiologie et de Santé Publique, GRC-UPMC 08 (EEMOIS); AP-HP, Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital, Department of Rheumatology, Paris, France.

Pil Hoejgaard, The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, The Capital Region of Denmark.

Ying Ying Leung, Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore.

Chris Lindsay, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA.

Vibeke Strand, Division of Immunology, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA.

Désirée van der Heijde, Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Laura Coates, Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, University of Leeds and Leeds Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds UK.

Lihi Eder, Women's College Research Institute, Women's College Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Neil McHugh, Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, UK.

Umut Kalyoncu, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Hacettepe University Ankara, Turkey.

Ingrid Steinkoenig, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Alexis Ogdie, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

References

- 1.Tunis SR, Clarke M, Gorst SL, Gargon E, Blazeby JM, Altman DG, et al. Improving the relevance and consistency of outcomes in comparative effectiveness research. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5:193–205. doi: 10.2217/cer-2015-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boers M, Brooks P, Strand CV, Tugwell P. The OMERACT filter for Outcome Measures in Rheumatology. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:198–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boers M, Kirwan J, Tugwell P, Beaton D, Bingham CO, 3rd, Conaghan PG, et al. The OMERACT Handbook. OMERACT. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Strand V, Healy P, Helliwell PS, Fitzgerald O, et al. Consensus on a core set of domains for psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1167–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d'Agostino MA, et al. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:745–753. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Soriano ER, Laura Acosta Felquer M, Armstrong AW, et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2015. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1060–1071. doi: 10.1002/art.39573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirwan JR, de Wit M, Bingham CO, 3rd, Leong A, Richards P, Tugwell P, et al. Patients as partners: Building on the experience of Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1334–1336. doi: 10.1002/art.39678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tillett W, Eder L, Goel N, De Wit M, Gladman DD, FitzGerald O, et al. Enhanced Patient Involvement and the Need to Revise the Core Set - Report from the Psoriatic Arthritis Working Group at OMERACT 2014. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2198–2203. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orbai AM, Mease PJ, de Wit M, Kalyoncu U, Campbell W, Tillett W, et al. Report of the GRAPPA-OMERACT Psoriatic Arthritis Working Group from the GRAPPA 2015 Annual Meeting. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:965–969. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalyoncu U, Ogdie A, Campbell W, Bingham CO, 3rd, de Wit M, Gladman DD, et al. Systematic literature review of domains assessed in psoriatic arthritis to inform the update of the psoriatic arthritis core domain set. RMD open. 2016;2:e000217. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palominos PE, Gaujoux-Viala C, Fautrel B, Dougados M, Gossec L. Clinical outcomes in psoriatic arthritis: A systematic literature review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:397–406. doi: 10.1002/acr.21552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gossec L, de Wit M, Kiltz U, Braun J, Kalyoncu U, Scrivo R, et al. A patient-derived and patient-reported outcome measure for assessing psoriatic arthritis: elaboration and preliminary validation of the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire, a 13-country EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1012–1019. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh JA, McFadden ML, Morgan MD, Sawitzke AD, Duffin KC, Krueger GG, et al. Work productivity loss and fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1670–1674. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudu T, Etcheto A, de Wit M, Heiberg T, Maccarone M, Balanescu A, et al. Fatigue in psoriatic arthritis - a cross-sectional study of 246 patients from 13 countries. Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83:439–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healy PJ, Helliwell PS. Measuring dactylitis in clinical trials: which is the best instrument to use? J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1302–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeley T, Williamson P, Callery P, Jones LL, Mathers J, Jones J, et al. The use of qualitative methods to inform Delphi surveys in core outcome set development. Trials. 2016;17:230. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1356-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van de Ven AH, Delbecq AL. The nominal group as a research instrument for exploratory health studies. American journal of public health. 1972;62:337–342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.62.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tillett W, de-Vries C, McHugh NJ. Work disability in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:275–283. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kavanaugh A, Gladman D, van der Heijde D, Purcaru O, Mease PJ. Clinical Responses in Joint and Skin Outcomes and Patient-Reported Outcomes are Associated with Increased Productivity in the Workplace and at Home in Psoriatic Arthritis Patients Treated with Certolizumab Pegol. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2015;18:A654. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogdie A, Schwartzman S, Husni ME. Recognizing and managing comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:118–126. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orbai AM, Ogdie A. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Psoriatic Arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2016;42:265–283. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaton DE, Terwee CB, Singh JA, Hawker GA, Patrick DL, Burke LB, et al. A Call for Evidence-based Decision Making When Selecting Outcome Measurement Instruments for Summary of Findings Tables in Systematic Reviews: Results from an OMERACT Working Group. J Rheumatol. 2015 doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141446. Epub 2015/09/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]