The midline oculomotor cerebellum plays a different role in smooth pursuit eye movements compared with the lateral, floccular complex and appears to be much less involved in direction learning in pursuit. The output from the oculomotor vermis during pursuit lies along a null-axis for saccades and vice versa. Thus the vermis can play independent roles in the two kinds of eye movement.

Keywords: cerebellum, motor learning, complex spikes, simple spikes, kinematic models

Abstract

We recorded the responses of Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis during smooth pursuit and saccadic eye movements. Our goal was to characterize the responses in the vermis using approaches that would allow direct comparisons with responses of Purkinje cells in another cerebellar area for pursuit, the floccular complex. Simple-spike firing of vermis Purkinje cells is direction selective during both pursuit and saccades, but the preferred directions are sufficiently independent so that downstream circuits could decode signals to drive pursuit and saccades separately. Complex spikes also were direction selective during pursuit, and almost all Purkinje cells showed a peak in the probability of complex spikes during the initiation of pursuit in at least one direction. Unlike the floccular complex, the preferred directions for simple spikes and complex spikes were not opposite. The kinematics of smooth eye movement described the simple-spike responses of vermis Purkinje cells well. Sensitivities were similar to those in the floccular complex for eye position and considerably lower for eye velocity and acceleration. The kinematic relations were quite different for saccades vs. pursuit, supporting the idea that the contributions from the vermis to each kind of movement could contribute independently in downstream areas. Finally, neither the complex-spike nor the simple-spike responses of vermis Purkinje cells were appropriate to support direction learning in pursuit. Complex spikes were not triggered reliably by an instructive change in target direction; simple-spike responses showed very small amounts of learning. We conclude that the vermis plays a different role in pursuit eye movements compared with the floccular complex.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The midline oculomotor cerebellum plays a different role in smooth pursuit eye movements compared with the lateral, floccular complex and appears to be much less involved in direction learning in pursuit. The output from the oculomotor vermis during pursuit lies along a null-axis for saccades and vice versa. Thus the vermis can play independent roles in the two kinds of eye movement.

the cerebellum plays an important role in eye movements, with different regions implicated in different kinds of eye movements. The control of any one type of eye movement probably results from the coordinated action of multiple lobules of the cerebellum, with each lobule independently adjusting cerebellar outflow directed toward the motor periphery (Thier 2011; Voogd et al. 2012). The floccular complex and the oculomotor vermis play important roles in saccadic and smooth pursuit eye movements, two oculomotor subsystems that serve, respectively, to point the fovea at objects of interest and to rotate the eye smoothly to keep the images from moving objects relatively stationary on the retina (Lisberger 2010). The general doctrine is that the floccular complex is more important for pursuit while the vermis is potentially important for both saccades and pursuit (Robinson and Fuchs 2001). In the present paper, we evaluate how the oculomotor regions of the cerebellum cooperate to control pursuit eye movements. We do so by recording the responses of Purkinje cells in the vermis during both saccades and pursuit and by comparing those responses with available data on the responses of floccular Purkinje cells during pursuit.

We know a great deal about the signals conveyed by the output neurons in the floccular complex and their targets in the deep cerebellar nuclei during pursuit (Fukushima et al. 1999; Joshua and Lisberger 2014; Shidara et al. 1993). Lesion studies have repeatedly demonstrated how critical the floccular complex is for pursuit (Rambold et al. 2002; Zee et al. 1981). Several recent papers have highlighted a critical role for the floccular complex in the directional adaptation of smooth pursuit eye movements (Medina and Lisberger 2008; Yang and Lisberger 2013, 2014a). Each of these different aspects of the function of the floccular complex can be understood quantitatively in terms of the simple-spike discharge of floccular Purkinje cells and their disynaptic connections to extraocular motoneurons. We strive to achieve the same level of understanding for the oculomotor vermis.

Most previous research on the oculomotor vermis has focused on its role in the control of saccadic eye movements (Herzfeld et al. 2015; Noda and Fujikado 1987; Thier et al. 2000). We do know that Purkinje cells in the vermis discharge in relation to pursuit (Dash et al. 2012; Sato and Noda 1992; Suzuki et al. 1981) and that lesions of the vermis cause deficits in pursuit (Takagi et al. 2000). Still, there is a large gap between the knowledge bases for the floccular complex and the vermis, mainly because the experimental approach in the floccular complex has used a wider range of pursuit behaviors. To better understand the role of the vermis in pursuit, we need to know more about such basic properties as how climbing fiber responses of Purkinje cells discharge in pursuit tasks. We also need to add to existing knowledge about how simple-spike firing correlates with the kinematics of the eye movement (Dash et al. 2012), how the population responses differ for pursuit vs. saccadic eye movements (Sun et al. 2017), and whether the output from the vermis changes during motor learning in pursuit (Dash et al. 2013).

Our goal in the present paper is to provide a quantitative description of the response properties of Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis. We recorded Purkinje cell activity as monkeys performed a battery of pursuit and saccade tasks that were customized to allow comparison with floccular responses from our prior publications. Others also have reported the responses of Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis during pursuit, and we have tried to supplement those reports in three ways. First, we have focused on responses in relation to the eye movements themselves, rather than the cognitive aspects of eye movements (Kurkin et al. 2014). Second, we facilitated a direct comparison between the roles of the oculomotor vermis and the floccular complex in pursuit eye movements by using the same behavioral, recording, and analysis procedures that already have been successful in the floccular complex (Krauzlis and Lisberger 1996; Medina and Lisberger 2008; 2007) Third, we have gone beyond the rather statistical analysis in a series of recent papers (Dash et al. 2012, 2013; Sun et al. 2017) and attempted to enhance our biological understanding of the area with an analysis approach that is tied more closely to the temporal response properties of the Purkinje cells.

In the final analysis, our results provide a thorough understanding of the responses of Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis. Our paper includes some completely new lines of experiment and analysis, some replication of knowledge that already existed, and some degree of correction of the prior literature. Ultimately our findings demonstrate that the oculomotor vermis and the floccular complex have very different basic response properties, directional tuning, trial-by-trial correlations, and neural learning. They also suggest that the vermis contains quite different representations of pursuit and saccades and that appropriate decoders could use the population response in the vermis to control both movement types independently. From these findings, we conclude that the vermis could participate independently in pursuit and saccades and probably plays a more modulatory role in the control of smooth pursuit than initially hypothesized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We report the responses during pursuit eye movements of 130 Purkinje cells recorded in the oculomotor vermis of two male rhesus macaque monkeys (Macaca Mulatta). Procedures for data acquisition were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Duke University and were in compliance with the National Institute of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. We also report analyses of neural and behavioral data collected in a prior study (Medina and Lisberger 2007) from 48 Purkinje cells in the floccular complex of two different male rhesus monkeys. We use these two sets of data to compare responses between the oculomotor vermis and the floccular complex in behavioral conditions described below.

Surgical and Recording Procedures

We implanted each monkey (Ramachandran and Lisberger 2005) with a head holder to prevent head movements during experiments and a scleral search coil for the measurement of eye position using the magnetic search coil method. We next trained the monkeys to track spots of light that moved across a video monitor positioned 30 to 40 cm away from the monkey’s eyes. Then, we implanted a stainless steel chamber, positioned laterally and at an angle of 20° to gain access to the oculomotor vermis while avoiding the sagittal sinus (stereotaxic coordinates ML 0, 16 mm posterior to the interaural line).

For each daily experiment, we lowered a guide tube to ~2 mm above the tentorium and used a hydraulic microdrive (Narishige MO-97) to advance a single microelectrode (Alpha Omega) through the tentorium and into the oculomotor vermis. We usually coated the electrode tip with a dalic iron solution (Sifco AFC) to reduce impedance to values between 200 and 500 kΩ. Potentials from the electrode were passed through an extracellular amplifier (Dagan) and a programmable filter (Krohn-Hite) that bandpass filtered the signals between 300 and 5,000 Hz before they were digitized at 25 KHz by custom software. For online analyses during experiments, spike times of Purkinje cells were registered using a window discriminator (Bak Instruments). Eye signals were filtered and differentiated using an analog circuit that differentiated signals of frequencies up to 25 Hz and filtered out signals of higher frequencies (−20 dB per decade). The processed signals were digitized and stored at 1 kHz on each channel.

Entry into the oculomotor vermis was confirmed by the presence of eye movement modulated units as well as audible background “swishing” activity modulated by eye movements (Noda and Fujikado 1987). Once the electrode was in the oculomotor vermis, we attempted to isolate Purkinje cells with clear evidence of both complex-spike and simple-spike responses. For data analysis after the experiment, we used custom spike-sorting software developed in our laboratory to mark simple-spike and complex-spike activity from our recorded neural data. Of the 130 Purkinje cells that showed complex spikes at some point during the recording session, 125 had complex-spike-related activity that was maintained throughout our recording protocol with a postcomplex-spike pause in simple-spike activity of at least 10 ms.

Behavioral Tasks

We presented target motions in trials that lasted 2 to 3 s. Each trial began with the monkey fixating on a white dot that appeared on the screen in front of him for 400 to 600 ms, enforced via an invisible 2 × 2° window about the dot’s center. Then, the target stepped 3° away from the future direction of motion and simultaneously began to move in the opposite direction at 20°/s for 750 ms [“step-ramp” target motion, after Rashbass (1961)]. Following a grace period of 200 ms, the monkey was required to track the target to within an invisible 2 × 2° window about the target. Finally, the target stepped forward 1° in the direction of motion and the monkey was required to maintain fixation on the target for a variable period of time. If he successfully met the fixation requirements throughout the task, the monkey received liquid reinforcement for completing the current trial before moving on to the next trial.

Tuning task.

The directions of target motion were chosen from 8 cardinal and oblique directions and presented in random order, until we accumulated 10 trials in each direction of motion. Online analysis of the responses in the tuning task allowed us to estimate the direction tuning of every Purkinje cell and then to choose the parameters of target motion in subsequent tasks.

Visually guided saccade task.

Saccade trials began with the monkey fixating on a spot of light. After 500 ms of sustained fixation, the target jumped 10° to one of eight radially spaced positions. The monkey was required to saccade to the target and hold fixation for 500 ms to receive liquid reinforcement.

Pursuit task.

For 79 Purkinje cells (52 from monkey Y and 27 from monkey V), the monkey pursued ~100 trials of target motion at 20°/s in the direction that elicited the largest change in simple-spike response relative to baseline. Sometimes this direction led to an increase in firing rate for the neuron in question, and other times it led to a decrease in firing rate. In monkey Y, we supplemented the target motions at 20°/s with ~50 randomly interspersed trials where the target could move at speeds of 10 or 30°/s. In monkey V, we also supplemented the preferred-direction target motions with ~100 randomly interspersed target motions in the opposite direction at 20°/s. These counterbalancing trials helped to reduce anticipatory responses.

Pursuit adaptation.

Target motion began as a step-ramp target motion at 20°/s, as in the pursuit tasks described above. After 250 ms of target motion, we added a 400-ms duration pulse of target motion at 30°/s in a direction orthogonal to the initial target motion, following the paradigm of Medina et al. (2005). We call the initial direction of motion the pursuit direction and the orthogonal component of motion the learning direction. Repeated presentation of the same pursuit adaptation trial caused the gradual emergence a component of eye velocity that was in the learning direction and that started ~50 ms before the onset of target motion in the learning direction. In the vermis, we recorded from 53 Purkinje cells (26 in monkey V, 27 in monkey Y) during 160 to 1,000 repetitions of a given pursuit adaptation trial. In some sessions, we recorded two blocks of pursuit adaptation trials with different learning and pursuit directions.

All together, we were able to analyze 75 sets of learning trials across our population of 53 Purkinje cells. Pursuit and learning directions were always orthogonal to one another and were chosen using our online estimates of the movement field of each Purkinje cell to maximize our chances of observing firing rate changes across learning. A block of learning trials followed at least 20 baseline trials where the target moved in the pursuit direction only. When we ran two sets of learning trials during a single recording session, each set of learning trials was followed by a minimum of 50 “wash-out” trials where the target moved only in the pursuit direction.

Data Analysis

All analysis was performed in MATLAB (Mathworks). In addition, we used a third party MATLAB package, the circular statistics toolbox (Berens 2009) for the calculation of preferred direction.

For analysis of pursuit eye movements, the digitized horizontal and vertical eye position traces were filtered offline using a zero-phase two-pole Butterworth low-pass filter with a cutoff of 25 Hz and then were differentiated numerically to obtain eye velocity. The process was repeated to obtain eye acceleration. Before numerical differentiation to determine pursuit acceleration, we replaced the spikes of eye velocity during catch-up saccades with a linearly interpolated line that connected the start and stop times of each saccade. For analysis of saccade kinematics, we filtered the eye position traces using a zero-phase two-pole Butterworth low-pass filter with a cutoff of 175 Hz before numerical differentiation to obtain eye velocity and eye acceleration.

Most of our analyses of neural responses were performed on the firing rates of Purkinje cell simple spikes, calculated as the inverse of the interspike interval using a previously published method (Lisberger and Pavelko 1986). For visualization in our figures, we smoothed the firing rate with a 10-ms Gaussian kernel and applied the denoising method of (Churchland et al. 2010). Briefly, this method first applies principle components analysis to a “c-by-t” matrix of response condition by time. It then reconstructs the data from the set of principle components, per each neuron, that account for at least 90% of the original data variance. Complex spikes were marked by viewing each individual spike train and then were analyzed by either 1) using a sliding window of duration 100 ms to calculate the probability of a complex spike as a function of time or 2) calculating probability after binning complex spikes in sequential, discrete 100-ms intervals.

Several of our data analyses required that we fit the time-varying average firing rate with regression models based on the kinematics of eye movement. The equations for the regression models appear in the results. In pursuit data, we replaced saccades with NaNs in the eye position, velocity, and acceleration traces. To fit each model to the data, we used the regress function in MATLAB for time leads and lags (Δt) between kinematic and neural data that varied systematically in the range of −50 to 50 ms. We report the fit for the value of Δt that led to the maximal variance accounted for in the firing rate of each Purkinje cell.

RESULTS

Direction Selectivity of Purkinje Cell Simple Spikes in the Oculomotor Vermis

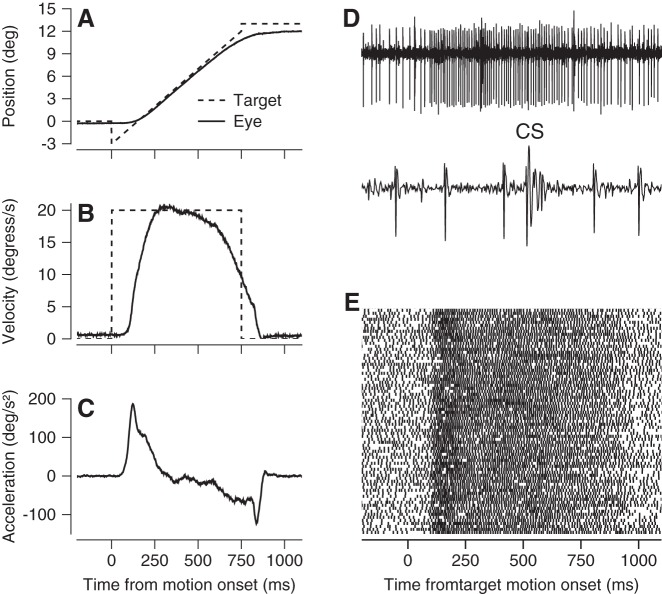

Step-ramp target motion evoked reliable initiation of pursuit, usually with saccades either absent or delayed well after the interval of rapid eye acceleration. Figure 1, A–C, shows typical averages of eye position, velocity, and acceleration across multiple repetitions of the same target motion. The precision and accuracy of the measurement of the parameters of eye movement enable the quantitative analyses presented in this paper and the comparison with the results of similar experiments in the floccular complex.

Fig. 1.

Example recording from a Purkinje cell in the oculomotor vermis during pursuit eye movements. A–C: averages of eye and target position, velocity, and acceleration vs. time for step-ramp target motion. Dashed and solid lines show target and eye kinematics, respectively. D: extracellular potentials from a Purkinje cell on slow and fast time base, showing both simple spikes and 1 complex spike (labeled CS). E: raster showing simple-spike times during 100 repetitions of the same target motion and pursuit eye movement. Each line shows data from 1 trial, and each dot indicates the time of occurrence of 1 action potential.

We identified Purkinje cells by the presence of their characteristic complex spike, interspersed with simple spikes during pursuit initiation (Fig. 1D). During the initiation of pursuit for step-ramp target motion, many Purkinje cells showed strong modulation of simple-spike firing that started around the time of the initiation of pursuit and continued throughout steady-state tracking (Fig. 1E).

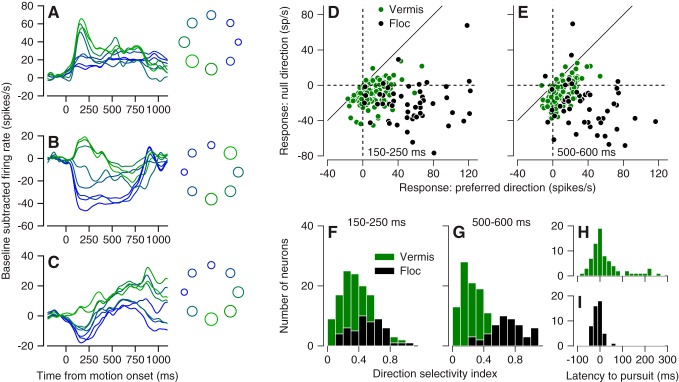

Most of the 130 Purkinje cells we studied in the vermis showed direction tuning for smooth pursuit eye movements, even though the response profiles were quite variable among neurons. For example, the three Purkinje cells in Fig. 2, A–C, showed increases in simple-spike firing in all directions (Fig. 2A), increases in firing for the preferred direction and decreases for opposite directions (Fig. 2B), and decreases in firing for all directions (Fig. 2C). In addition, the time courses showed some reversals, with initial increases in firing turning to decreases in some instances or vice versa. In Fig. 2, A–C, we measured the number of spikes in the intervals from 150 to 250 ms after the onset of target motion, minus the number expected given the baseline firing rate during fixation before the onset of pursuit. This early measurement interval quantifies the response during the transient associated with the initiation of pursuit. Both the traces and the bubble plots in Fig. 2, A–C, right, have been color coded according to the size of the response. The directions of pursuit that elicited the highest vs. lowest number of spikes are shaded green vs. blue. Similar coding with increases and/or decreases in firing rate also occurs in vermis Purkinje cells during saccades (Dash et al. 2012; Herzfeld et al. 2015; Hong et al. 2016).

Fig. 2.

Direction tuning during pursuit for the population of Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis. A–C: firing rate vs. time for pursuit in 8 directions in 3 example Purkinje cells. Traces are color-coded to match the bubble plots at right, where each circle is plotted in polar coordinates to indicate the direction of target motion and the size of the circle indicates simple-spike firing rate in the interval from 150 to 250 ms after the onset of target motion. D and E: scatterplots showing simple-spike firing rate vs. baseline for each Purkinje cell in our sample, with the null and preferred directions on the y- and x-axis. D and E show firing rate measured 150–250 and 500–600 ms after the onset of target motion. F and G: distribution of direction selectivity index for simple-spike firing rate measured 150–250 or 500–600 ms after the onset of target motion. H and I: latency of simple-spike firing rate in the preferred direction, relative to the onset of pursuit for Purkinje cells in the vermis (H) and floccular complex (Floc; I). In D–H, green and black show data from the oculomotor vermis and the floccular complex.

For each Purkinje cell in our sample, we used the circular mean (Fisher 1993) to quantify the preferred direction. We used averages of firing rate across multiple target motions in each direction and quantified the average firing rate across two 100-ms intervals, during the initiation of pursuit (150–250 ms after target motion onset) and steady-state pursuit (500–600 ms after target motion onset). Of the sampled directions of pursuit directions, we chose the direction that was closest to the circular mean as the “preferred” direction and the opposite direction as the “null” direction.

We were particularly interested in determining how the structure of directionality differed between cells in the oculomotor vermis and the floccular complex. Relative to the baseline firing rate during fixation, the majority of vermis Purkinje cells showed increases in firing for their preferred directions and decreases for the null direction and therefore plotted in quadrant IV in Fig. 2, D and E, green symbols). However, many vermis Purkinje cells showed either increases in firing in both the preferred and null direction or decreases in firing in both directions. In contrast, floccular Purkinje cells (black symbols) plotted almost uniformly in quadrant IV in Fig. 2, D and E, indicating that they showed an increase in firing rate in their preferred direction and a decrease of firing rate in their null direction across the movement epoch. Examination of Fig. 2, D and E, also shows that vermis responses were generally weaker than floccular responses.

During both the initiation of pursuit and steady-state pursuit, vermis Purkinje cells were less direction selective than were floccular Purkinje cells. For each neuron, we calculated the direction selectivity index as:

| (1) |

where FRNULL and FRPREF are the absolute (not baseline subtracted) firing rates in the preferred and null direction. DSI will have a value of 1 for Purkinje cells that show suppression to zero spiking activity in the null direction and a value of zero for Purkinje cells that show the same response in the preferred and null direction. On average, directional selectivity indexes were lower in the vermis by comparison to the floccular complex during the initiation of pursuit (Fig. 2F, 0.327 vs. 0.5), and the difference was still larger during steady-state pursuit (Fig. 2G, 0.28 vs. 0.69).

The distributions of neural latency relative to pursuit latency were similar for the two structures, with a somewhat broader distribution for the vermis compared with the floccular complex (Fig. 2, H and I). On average, neural responses in the vermis lagged pursuit by 35 ms. The mean latency of neural responses in the floccular complex was the same as the mean latency of pursuit. The small number of vermis Purkinje cells with very long latencies drives the difference in the means, and many vermis Purkinje cells had latencies that were clearly short enough to drive the initial pursuit movement.

Responses During Pursuit vs. Saccadic Eye Movements

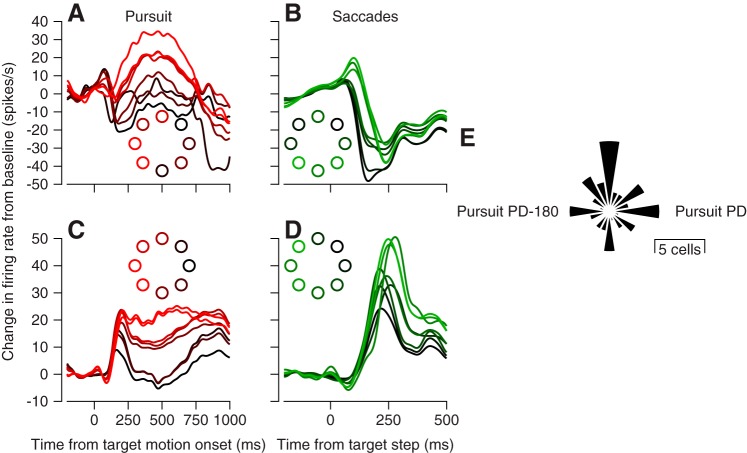

Most research on the oculomotor vermis has focused on its role in the control of saccadic eye movements (Robinson and Fuchs 2001). To connect to that literature, we compared the direction tuning of 84 Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis for pursuit and saccadic eye movement trials.

We found variable relationships between directional preference for pursuit and saccades. In Fig. 3, for example, one neuron showed the largest responses for leftward pursuit (Fig. 3A) and downward saccades, while the other showed the largest responses for leftward pursuit (Fig. 3C) and leftward saccades (Fig. 3D). Across our sample of vermis Purkinje cells, we quantified preferred directions for simple-spike responses in the last 50 ms before the peak of saccadic eye velocity and during the first 100 ms of pursuit after using an objective method to identify pursuit onset (Lee and Lisberger 2013). This approach provided a fair comparison of responses during comparable intervals, when each behavior operates in an open-loop manner without influence of visual feedback. We then estimated the preferred direction using the circular mean, based on trial-averaged responses as before, and we computed the difference in the preferred directions of individual Purkinje cells during smooth pursuit vs. saccades. There was a tendency for the preferred direction for saccades to be oriented along one of four cardinal directions relative to the preferred direction for pursuit (Fig. 3E), but the difference in direction preferences did not show any statistically significant organization (Rayleigh’s test, P = 0.1211).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of direction tuning in oculomotor vermis for pursuit and saccadic eye movements. A and C: simple-spike firing vs. time during pursuit in 8 directions for 2 example Purkinje cells. B and D: simple-spike firing vs. time during 10° amplitude saccades in 8 directions for the same 2 Purkinje cells. Colors of traces correspond to colors of dots in each inset and indicate the direction of the target motion for pursuit or the target step for saccades. E: polar histogram indicating the distribution of the difference in preferred direction (PD) of vermis Purkinje cells for saccades vs. pursuit.

We next show that the tuning of vermis Purkinje cells for saccades and pursuit is sufficiently independent so that downstream areas could decode population activity independently for the two kinds of movement. For each neuron in our sample, we selected four traces of the firing rate as a function of time for the responses during both saccades and pursuit in the preferred directions of both saccades and pursuit. Not surprisingly, we obtained clear modulation of firing rate when we averaged all the traces for responses during pursuit in the pursuit preferred direction (Fig. 4C) and during saccades in the saccade preferred direction (Fig. 4B). However, we saw very little modulation of firing rate when we averaged responses during saccades in the pursuit preferred direction (Fig. 4A) or during pursuit in the saccade preferred direction (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, if we aligned all saccade direction tuning curves according to their preferred direction and created a population direction-tuning curve, we observed strong tuning (Fig. 4C, open symbols). If we aligned the same saccade direction-tuning curves according to each neuron’s pursuit preferred direction, we observed very little tuning in the population direction-tuning curve (Fig. 4C, filled symbols). The opposite results emerged for pursuit direction tuning (Fig. 4F). Thus signals to guide pursuit could be extracted from the population while saccade responses are averaged away or vice versa.

Fig. 4.

Independent direction tuning for pursuit and saccades in the oculomotor vermis. A and B: simple-spike firing rate during saccades vs. time averaged across the population of Purkinje cells for responses in the preferred direction for pursuit (A) or saccades (B). D and E: simple-spike firing rate during pursuit vs. time averaged across the population of Purkinje cells for responses in the preferred direction for pursuit (D) or saccades (E). In A, B, D, and E, dark curves show average firing rate and the light gray ribbon shows the standard error of the mean. C: direction tuning for saccades. F: direction tuning for pursuit. In C and F, filled and open symbols show average direction tuning curves for the full sample of Purkinje cells where 0° was chosen to be the preferred direction for pursuit or saccades, respectively.

Responsiveness of Purkinje Cell Complex Spikes in the Oculomotor Vermis to Pursuit

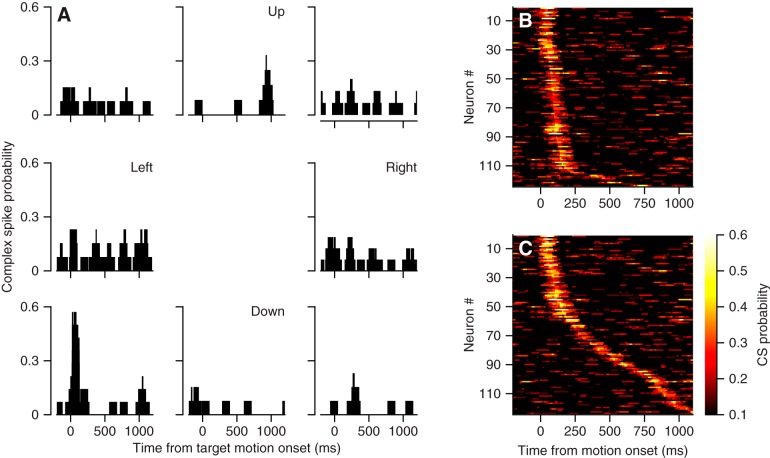

Many Purkinje cells in the vermis show strong complex-spike responses during pursuit initiation. For example, the Purkinje cell illustrated in Fig. 5A exhibited a brisk transient increase in the probability of a complex spike for the initiation of pursuit down and to the left. To analyze these data objectively across our sample of 124 Purkinje cells, we found the peak complex-spike probability within a 100-ms sliding window in the interval from 75 to 1,200 ms after target motion onset, across all eight directions of pursuit. We summarized the data in Fig. 5C for the direction of target motion that evoked the highest probability of a complex spike at any time during the pursuit movement. We also found the peak complex-spike probability in the interval from 50 to 250 ms after target motion onset and summarized the data in Fig. 5B, again for the direction of target motion that evoked the highest probability of a complex spike during pursuit initiation. The two representations in Fig. 5, B and C, are different because the direction that produced the largest probability of a complex spike during the initiation of pursuit frequently was different from the direction that yielded the largest probability any time during the pursuit trial.

Fig. 5.

Complex-spike responses of Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis during pursuit eye movements. A: direction tuning for an example Purkinje cell. Each graph is positioned to indicate the direction of target motion and the histograms show the probability of a complex spike as a function of time in a sliding 100-ms bin. B and C: summary of probability of complex spikes during pursuit in the preferred direction, where preferred direction is defined in B by the largest response in the interval from 50 to 250 ms after the onset of target motion and in C by the largest response across the entire trial. Here, the colors indicate the probability of a complex spike in a 100-ms sliding bin, each horizontal line shows data for 1 Purkinje cell, and time goes from left to right.

The vast majority of Purkinje cells showed a time when complex-spike probability was quite high (Fig. 5C). Essentially all Purkinje cells showed a peak probability at least twice the probability of 0.1 expected in a 100-ms interval given a spontaneous rate of approximately one complex spike per second. Focusing only on the interval of pursuit initiation, 113/124 Purkinje cells reached a peak complex-spike probability of at least 0.2 within the interval from 50 to 250 ms after target motion onset for at least one direction of target motion (Fig. 5B). Most complex-spike responses were more sharply directional than simple-spike responses, with a 44% reduction below baseline complex-spike probability during the initiation of pursuit in the direction 180° opposite to the pursuit direction that elicited maximal complex spikes.

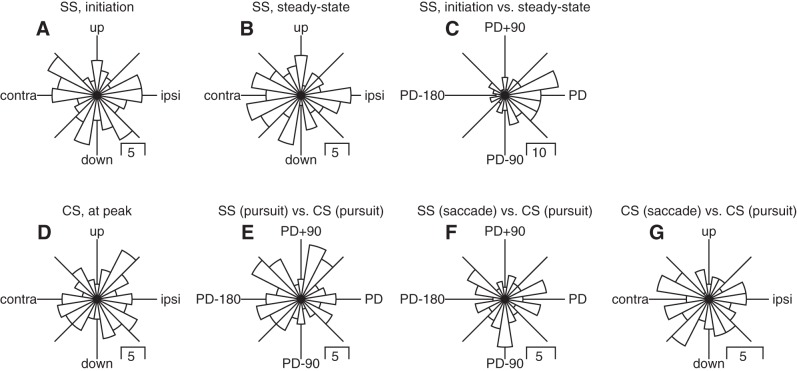

Directional Organization of Purkinje Cell Simple and Complex-Spike Signals

The distributions of preferred directions for simple-spike firing rate were uniform both during the initiation of pursuit (Fig. 6A, Rayleigh’s test, P = 0.59) and during steady-state pursuit (Fig. 6B, Rayleigh’s test, P = 0.29). However, simple spikes maintained the same preferred directions across the initiation and steady-state pursuit intervals (Fig. 4C, Rayleigh’s test, P < <0.01). To assess the preferred direction of complex-spike responses during pursuit, we again calculated the circular mean of vectors defined by the peak probability of complex spikes in sliding 100-ms duration windows within the interval from 50 to 250 ms after the initiation of pursuit. The preferred direction of complex-spike responses was uniformly distributed (Fig. 6D, Rayleigh’s test, P = 0.52), and the difference between the preferred directions for complex-spike and simple-spike responses also was statistically uniform (Fig. 6E, Rayleigh’s test, P = 0.13). Importantly, it did not show the opposite direction tuning typical of the floccular complex (Badura et al. 2013; Stone and Lisberger 1990).

Fig. 6.

Direction tuning of simple spikes (SS) and complex spikes for the population of Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis during saccades and pursuit. A–G contain a polar histogram showing the distribution of a particular measure of preferred direction across the full sample of Purkinje cells. A: simple-spike firing from 150 to 250 ms after the onset of target motion. B: simple-spike firing from 500 to 600 ms after the onset of target motion. C: difference for simple-spike firing between 150 and 250 and 500–600 ms after the onset of target motion. D: peak complex-spike probability in the interval from 50 to 250 ms after the onset of target motion. E: difference between preferred simple-spike and complex-spike direction, both in the interval from 50 to 250 ms after the onset of target motion. F: difference between preferred simple-spike direction during saccades and preferred complex-spike direction during pursuit initiation. G: difference between preferred complex-spike directions during saccades and pursuit.

The small position errors hypothesized to elicit catch-up saccades during pursuit are also potent drivers of Purkinje cell complex spikes in the oculomotor vermis (Soetedjo et al. 2008). Therefore, it is possible that the strong complex-spike responses we observed in this interval may be more related to signals that drive catch-up saccades as opposed to visual or motor signals that are more closely linked to pursuit. We have three observations that argue against this possibility. First, complex-spike responses are directionally tuned during the initiation of pursuit, in the interval before saccades occur. Second, the difference between preferred directions for complex-spike responses during pursuit and simple-spike responses during saccades was statistically uniform (Fig. 6F, Rayleigh’s test, P = 0.60). This is different from the expectation if the complex-spike responses really were driven by saccadic errors: because catch-up saccades tend to be in the same direction repeatedly, complex-spike responses actually related to saccades might be expected to cause modulation that still is related to the preferred direction for pursuit. Third, the direction preferences of complex-spike responses during pursuit were not related to those during saccades (Fig. 6G, Rayleigh’s test, P = 0.28).

In summary, the direction-tuning of simple spikes in the oculomotor vermis remains stable across the pursuit response within most individual Purkinje cells, but the tuning structure does not fall into any clear channels of directional tuning like those in the floccular complex, where most Purkinje cells prefer ipsiversive or downward pursuit (Krauzlis and Lisberger 1996). Moreover, the relationship between simple- and complex-spike preferred directions during pursuit is different from the opponent organization found in the floccular complex (Stone and Lisberger 1990). This observed relationship is also different from the opponent organization reported in recent studies in the vermis that examined responses during saccades (Herzfeld et al. 2015).

Kinematic Sensitivity During Smooth Pursuit

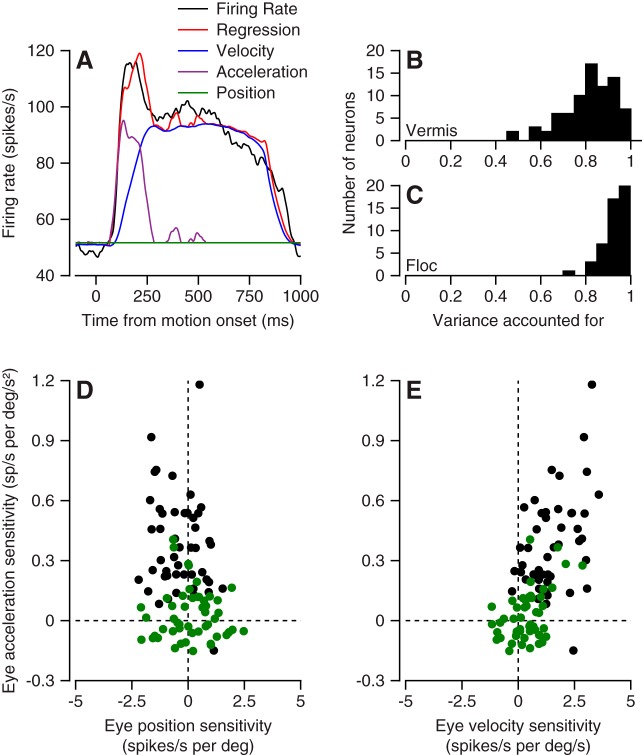

Now, we compare the sensitivity to the parameters of eye movement for 79 Purkinje cells recorded in the oculomotor vermis and 48 Purkinje cells recorded in the floccular complex while monkeys tracked a target moving in each neuron’s preferred direction for simple spikes. For this analysis, we selected Purkinje cells that had been studied during at least 100 repetitions of target motion in their preferred direction for simple spikes.

We quantified kinematic sensitivity using the approach of prior publications (Medina and Lisberger 2007; Shidara et al. 1993). We averaged the simple-spike firing rate of Purkinje cells over multiple repetitions of the same target motion and smoothed the average using a second-order digital Butterworth low-pass filter, with a cutoff frequency of 25 Hz. Then, we performed regression analysis against a linear combination of eye position, velocity, and acceleration. The model has the form:

| (2) |

where k, r, ap, an, rr, and Δt are free parameters and the dots over the E’s indicate derivatives of eye position. The variable rr signifies resting rate, and Δt signifies the optimal time shift parameter for each neuron. To improve the fits, we allowed the model to select separate coefficients for the positive and negative components of eye acceleration, a strategy that also improved the fits for floccular Purkinje cells (Medina and Lisberger 2009). We used the coefficients of the model and the components of eye movement to compute the contribution to firing rate for eye position (Fig. 7A, dark green trace), velocity (blue trace), and the positive component of acceleration (purple trace).

Fig. 7.

Comparison of relationship between simple-spike firing and eye kinematics during pursuit for oculomotor vermis and floccular complex. A: firing rate vs. time showing the contribution of different kinematic components, according to the colors in the key. B and C: variance accounted for by Eq. 2 for Purkinje cells in oculomotor vermis (B) and floccular complex (C). D and E: scatterplots summarizing sensitivity to eye position, velocity, and acceleration for our full sample of Purkinje cells. Green and black symbols show data for oculomotor vermis and floccular complex.

A regression model based on the kinematics of eye movement does quite a good job of explaining the simple-spike firing rate of the vermis Purkinje cells in our sample (Fig. 7A), although the model performs better in the floccular complex. In the vermis, Eq. 2 accounted for ~80% of the variance in the time-varying mean firing rate of Purkinje cells (Fig. 7B). In the floccular complex, the same regression model accounted for more than 90% of the variance (Fig. 7C). These impressive levels of variance accounted for can be attributed to the fact that we fitted the regression model to averages across a fairly large number of trials. The variance accounted for is smaller if we average fewer trials. Furthermore, we agree with Dash et al. (2012) that the model would perform better on the population average from the vermis than it does on many of the individual Purkinje cells.

The coefficients of eye position, velocity, and acceleration differed markedly between Purkinje cells in the floccular complex and the oculomotor vermis. For the vermis, the strengths of the different components were relatively balanced on the scales we chose for our graphs (Fig. 7, D and E and E, green symbols), while floccular Purkinje cells emphasized eye acceleration (black symbols). The absolute eye position coefficient distributions were similar in the two structures, while floccular Purkinje cells showed larger sensitivities to both eye velocity and eye acceleration. Figure 7, D and E, also underscores a key difference between the structures, namely that floccular Purkinje cells respond much more strongly to pursuit than do their counterparts in the oculomotor vermis.

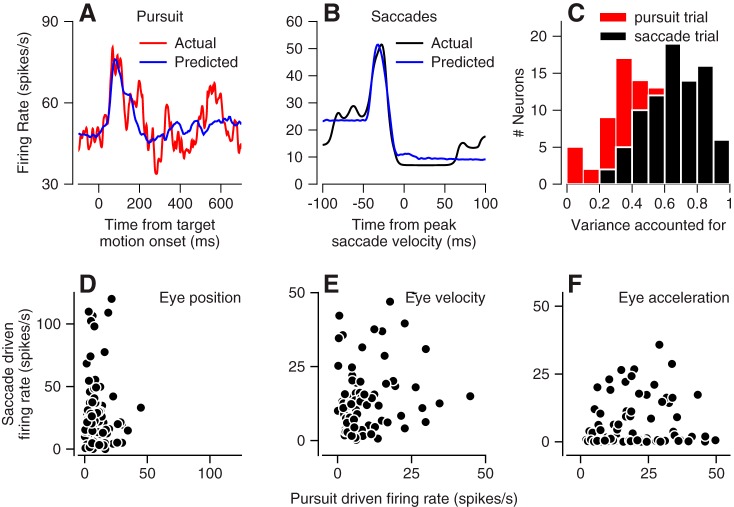

Different Kinematic Sensitivity for Pursuit vs. Saccades in the Oculomotor Vermis

A priori, it is possible that the vermis regulates a common motor parameter for saccades and pursuit (Krauzlis and Miles 1998; Robinson et al. 1993) or that it plays different roles for the two kinds of eye movements. To test these possibilities, we fitted a kinematic regression model separately to the simple-spike responses during pursuit and saccades in the preferred direction for each Purkinje cell. The two preferred directions could be the same, or different, depending on the tuning properties of each neuron. Here, we simplified the regression model slightly to avoid over fitting the saccadic response with the two components of eye acceleration:

| (3) |

We fitted Eq. 3 to the average simple-spike firing over ~10 trials for the time intervals from 200 ms before to 800 ms after pursuit onset, and from 200 ms before to 200 ms after peak saccadic velocity. Before fitting, the firing rate was smoothed with a first-order Butterworth low-pass filter, with a frequency cutoff of 50 Hz. We chose a higher cutoff frequency than the analyses presented above to avoid damping the sharper transient responses associated with saccadic eye movements. Here, we analyzed 84 Purkinje cells that showed significant direction tuning for both saccades and pursuit, and we used the direction tuning data with only 5–10 trials per direction of movement.

Overall, the regression model did a good job of capturing the main features of firing rate during both pursuit (Fig. 8, A and C, population average 47% of variance) and saccades (Fig. 8, B and C, population average 66% of variance). Across the population, the regression model accounted for more of the variance in the responses during saccades vs. during pursuit, a feature that may be due partially to the larger number of data points fitted for pursuit (n = 800) vs. saccades (n = 200). We also note that the variance accounted for during pursuit in Fig. 7C was considerably higher than in Fig. 8C because we averaged across at least 100 vs. only 5–10 trials in the two figures, respectively.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of relationship between simple-spike firing and eye kinematics in oculomotor vermis for pursuit vs. saccades. A and B: fits of Eq. 3 to simple-spike firing rate in an example Purkinje cell for pursuit (A) and saccades (B). C: variance accounted for in fits to data for pursuit and saccades. Pink and black bars show data for pursuit vs. saccades D–F: scatterplots summarizing size of firing rate responses eye position, velocity, and acceleration for our full sample of Purkinje cells. The y- and x-axes show data for saccades and pursuit.

The relationship between simple-spike firing in the vermis and the kinematics of eye movement was very different for pursuit and saccades. Here, we computed the peak firing rate contributed by each kinematic component of eye movement to allow a fair comparison between two kinds of eye movements with very different amplitudes of eye position, velocity, and acceleration. Figure 8, D–F, shows a lack of correlation between the responses during pursuit and saccades for all three components of the kinematic analysis: position, velocity, and acceleration. The correlation coefficients for these three components were 0.14 (P = 0.22), 0.26 (P = 0.02), and 0.13 (P = 0.24). We interpret these results as evidence against the idea that the vermis provides the same control of both pursuit and saccades. Rather there seems to be a movement-specific encoding of kinematics, indeed, one that is much more severe compared with what was found downstream in extraocular motoneurons (Sylvestre and Cullen 1999).

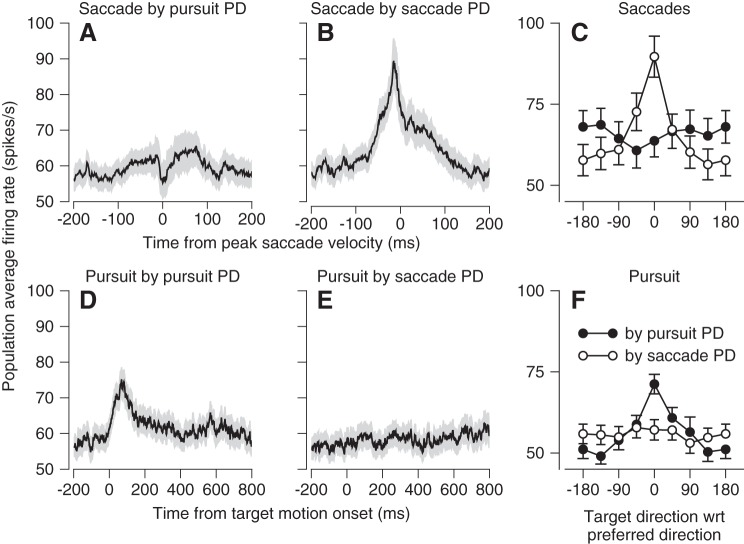

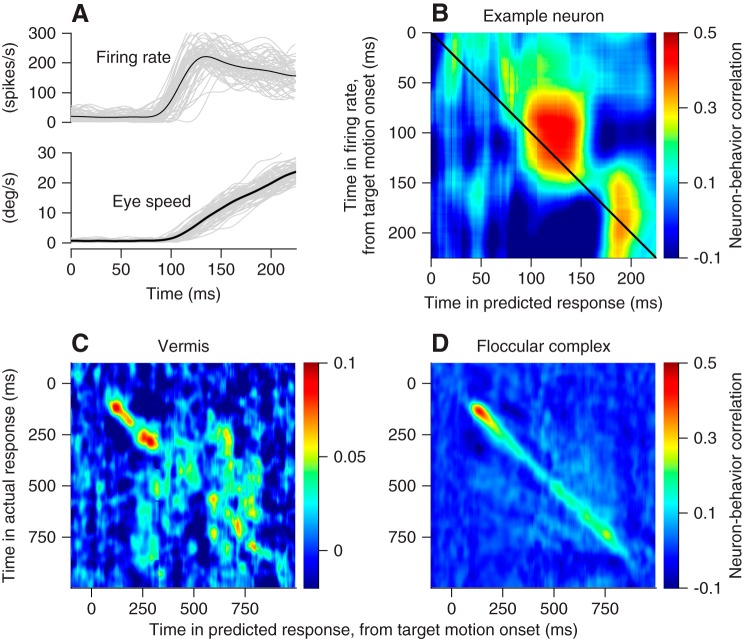

Trial-by-Trial Correlations Between Firing Rate and Pursuit

Our laboratory reported previously that trial-by-trial “neuron-behavior” correlations between firing rates in the floccular complex and concomitant behavioral variations in pursuit are quite high (Medina and Lisberger 2007) and higher than neuron-behavior correlations in the cortical pursuit structures upstream of the floccular complex (Lisberger 2010; Medina and Lisberger 2007). These neuron-behavior correlations are believed to arise from shared sources of variation in sensory structures upstream from the motor apparatus that drives pursuit (Hohl et al. 2013; Osborne et al. 2005). As one moves closer to the motor periphery neuron-behavior correlations increase and ultimately drive the trial-by-trial variation in pursuit (Joshua and Lisberger 2014). We next test the hypothesis that trial-by-trial correlations in this structure ought to be similar to those in the floccular complex as both inherit similar sensory and motor signals from the cerebral cortex.

We can analyze trial-by-trial “neuron-behavior correlations” because of the natural variation across repeated eye movement and neural responses to the same pursuit target motion (Fig. 9A). To do so correctly, we need to correlate behavior and neural responses using the same units. Therefore, we converted the eye movement for each behavioral trial into a predicted firing rate for that trial, using the regression coefficients from fitting Eq. 3 to the average responses for each neuron. Then, we correlated measured firing rate at each time across the trial with the predicted firing rate for each time and obtained a pseudo-color representation of neuron-behavior correlations (Fig. 9B). Here, each pixel represents a different combination of times in neural responses and behavior. For the example neuron, the blob of red pixels shows neuron-behavior correlations that reached 0.4 for times near 100 ms after the onset of target motion in firing rate and 125 ms after the onset of target motion in the predicted response. Note that we conducted this analysis on 79 vermis Purkinje cells and 48 floccular Purkinje cells that provided responses to more than 100 repetitions of target motion in the preferred direction for simple spikes.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of trial-by-trial neuron-behavior correlations in oculomotor vermis and floccular complex. A: example data from 1 Purkinje cell. Black traces show averages across trials and gray traces show single trials. B–D: each pixel uses color to show the trial-by-trial correlation coefficient between actual firing rate and the firing rate predicted by the regression fit at the times shown on the y- and x-axis. B: data for an example Purkinje cell in the oculomotor vermis. C: averages across all Purkinje cells recorded in the oculomotor vermis. D: averages across all Purkinje cells recorded in the floccular complex.

In the example neuron of Fig. 9B, the strongest neuron-behavior correlation during the initiation of pursuit occurred when firing rate preceded behavior. Averaging across Purkinje cells in the vermis revealed consistent neuron-behavior correlations, especially near the initiation of pursuit from 100 to 300 ms after the onset of target motion (Fig. 9C). However, by comparison with the results of the same analysis for Purkinje cells in the floccular complex (Fig. 9D), neuron-behavior correlations in the vermis were nearly five times smaller during the initiation of pursuit (note difference in color calibration bars) and essentially vanished after the initiation of pursuit. Thus the activity of single Purkinje cells in the vermis does not predict the current eye movement as well as does the activity of individual Purkinje cells in the floccular complex.

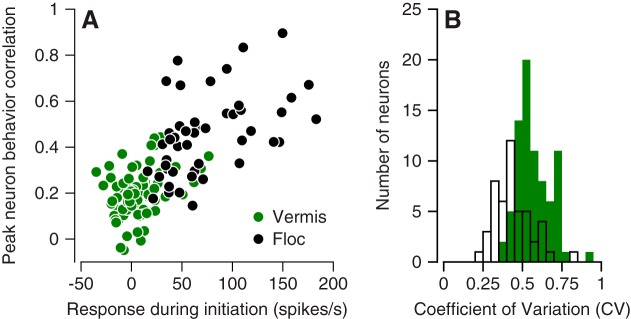

The properties of the responses during pursuit in each area can probably explain much of the difference in neuron-behavior correlations between the vermis and the floccular complex. First, in the floccular complex, we observed a linear relationship between the peak neuron-behavior correlation and the change in simple-spike firing rate during the initiation of pursuit (Fig. 10A, black symbols). The response amplitudes in the vermis and the neuron-behavior correlations both were smaller (Fig. 10A, green symbols), and the data from the two areas defined a single linear relationship. Second, higher variability in interspike intervals will cause lower values of neuron-behavior correlation (Schoppik et al. 2008). At least during baseline fixation before the onset of target motion, Purkinje cells in the vermis showed more interspike interval variation than did Purkinje cells in the floccular complex (Fig. 10B). Thus we would expect lower values of neuron-behavior correlation in the vermis on the basis of smaller responses during the initiation of pursuit and larger variation in interspike intervals. We conclude that the difference in neuron-behavior correlation between the vermis and the floccular complex might not have functional significance.

Fig. 10.

Quantitative comparison of neuron-behavior correlations in oculomotor vermis and floccular complex. A: scatterplot showing relationship between the peak neuron-behavior correlation and the peak response during pursuit initiation for all individual Purkinje cells. Green and black symbols show data for vermis and floccular complex. B: distribution of the coefficient of variation of interspike intervals during fixation at straight ahead for both samples of Purkinje cells: Green and white bars show data for vermis and floccular complex.

Effect of Direction Learning in Pursuit on Simple-Spike Responses

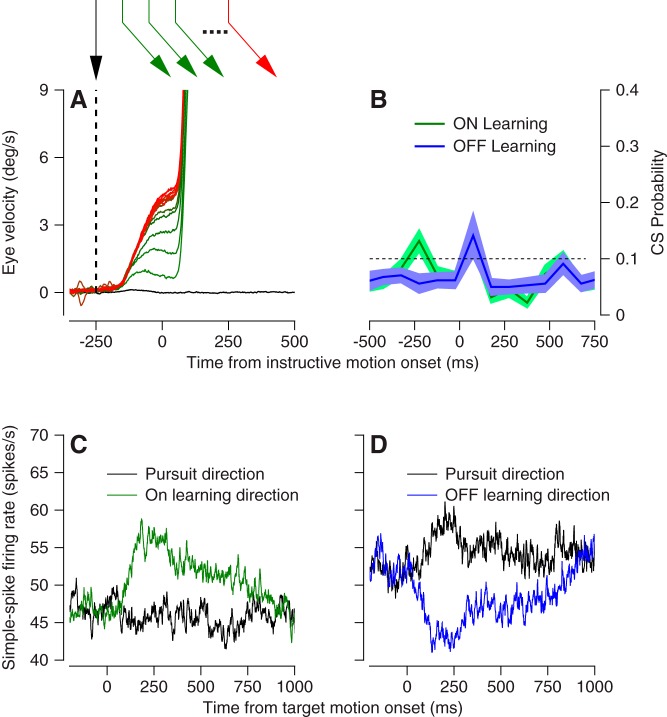

Pursuit adaptation occurs as an animal incorporates predictable changes in the direction or speed of a target into its tracking movements (Yang and Lisberger 2010). Multiple studies have established the floccular complex as a potentially important site for learning in pursuit eye movements (Medina and Lisberger 2008; Yang and Lisberger 2014a). Prior work has shown that the population response in the vermis does undergo some changes in simple-spike firing that would be appropriate to guide learning of the speed of pursuit (Dash et al. 2013). We now ask whether the responses of Purkinje cells in the vermis are compatible with the vermis as a site of direction learning for pursuit.

Monkeys performed a pursuit direction-adaptation task (Medina et al. 2005) where they repeatedly tracked a moving spot that changed its direction at a specified time following target motion onset. In each behavioral trial, the target moved first in what we will call the “pursuit” direction for 250 ms at 20°/s. Then, we introduced an instructive component of target motion at 30°/s in a direction orthogonal to the initial pursuit direction, termed the “learning” direction. Over repeated presentation of these learning trials, pursuit acquired a component of eye velocity in the learning direction that preceded instruction onset (Fig. 11A). For each of 75 Purkinje cells, we ran either one or two learning blocks of at least 160 learning trials with one initial pursuit direction and either one or both directions of orthogonal learning directions. Baseline blocks were preceded learning blocks to assess responses in the pursuit and learning directions for each Purkinje cell.

Fig. 11.

Experimental design to study direction learning in pursuit. A: eye velocity in the learning direction vs. time at different phases of a pursuit learning experiment. Colors of traces correspond to colors and temporal sequence of target motions, indicated in the schematic at top. B: average complex-spike probability vs. time across the full sample of Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis in learning trials designed to cause learning in either the on- or off-direction for the Purkinje cell under study. C and D: average firing rate vs. time in the prelearning baseline block, comparing data for tracking in the pursuit or learning directions for on-direction (C) or off-direction (D) learning blocks.

After the experiments, we categorized each learning block as an “on” or “off” learning block depending on whether the simple-spike response in the learning direction was more positive (Fig. 11C) or more negative (Fig. 11D) than in the pursuit direction. During the experiments, we had tried to optimize the pursuit and learning directions on the basis of each Purkinje cell’s simple-spike directional tuning, assessed online. Our goal was to maximize the firing rate differences we would expect based on each cell’s baseline response to target motion in the pursuit and learning directions. This effort was fairly successful. On average, there was about a 10 spike/s difference between simple-spike responses in the learning direction and pursuit direction, with on vs. off learning blocks defined by positive vs. negative differences.

Complex-spike responses in our learning blocks did not follow the expected pattern (Fig. 11B). First, the number of complex spikes evoked by the instructive change in target direction was not different between on- and off-learning blocks (compare red and blue traces). Second, the probability of complex-spike response reached a peak that averaged under 0.2 just after the onset of the instructive target motion. In contrast, most Purkinje cells in the floccular complex emit complex spikes with a probability that averages 0.4 during off-direction learning blocks (Medina and Lisberger 2008).

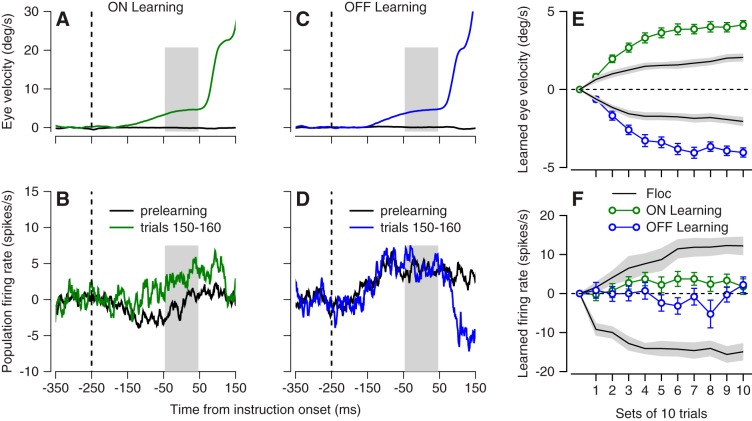

In the direction-learning paradigm, we observed very little learning in the simple-spike responses of vermis Purkinje cells. In the example Purkinje cell of Fig. 12, A and B, on-direction behavioral learning (Fig. 12A) was associated with a change in simple-spike firing rate of <5 spikes/s in the correct direction (Fig. 12B). In another example Purkinje cell (Fig. 12, C and D), off-direction behavioral learning (Fig. 12C) failed to cause a change in simple-spike firing rate (Fig. 12D). For quantitative analysis, we divided each block of trials into bins with 10 trials, averaged both eye velocity and simple-spike firing rate across the interval from 50 ms before to 50 ms after the onset of target motion, and subtracted the same measurements from the prelearning baseline trials. Behavioral learning curves during recordings from the vermis (Fig. 12E, blue and green symbols) were almost twice the amplitude of those during our laboratory’s prior recordings from the floccular complex (black curve). However, the learned changes in simple-spike firing in the vermis (Fig. 12F) were tiny compared with those recorded previously by Yang and Lisberger (2014b) in the floccular complex. We conclude that the vermis is not likely to be a major site of adaptation for the direction-learning paradigm.

Fig. 12.

Very small learned changes in simple-spike firing during direction learning in the oculomotor vermis. A and B: learned eye velocity (A) and change in simple-spike firing rate (C) for on-direction learning blocks in an example Purkinje cell. C and D: learned eye velocity (C) and change in simple-spike firing rate (D) for on-direction learning blocks in an example Purkinje cell. E: learning curves for eye velocity. F: learning curves for simple-spike firing rate. In E and F, green and blue symbols show averages across all experiments for on-direction and off-direction learning in the oculomotor vermis, and black traces summarize data from the floccular complex. Gray ribbons indicate means ± SE across floccular Purkinje cells.

DISCUSSION

We have analyzed the response properties of Purkinje cells recorded in the oculomotor vermis across a battery of oculomotor tasks that were designed to provide a quantitative description of vermis responses comparable with what is available for the floccular complex. Our results make the strong case that the oculomotor vermis operates differently from the floccular complex in nearly every circumstance that we have examined, including basic responses, tuning, trial-by-trial neuron-behavior correlations, and participation in direction learning. Some of our findings are entirely new, while others replicate or modify prior reports to some degree.

Control of Saccades vs. Pursuit by the Oculomotor Vermis

Many prior studies have attempted to cast the vermis as a structure that plays some common role in regulating smooth pursuit and saccadic eye movements (Krauzlis 2004; Krauzlis and Miles 1998; Robinson et al. 1997; Thier 2011). Our findings strongly argue against this viewpoint. First, there were clear differences in directional selectivity of simple-spike firing depending on whether an animal was pursuing a target or making a saccade to it. Indeed, when Purkinje cells were organized according to their preferred pursuit directions, the population became nonresponsive to saccades and vice versa. We term this encoding scheme “orthogonal,” and we note that it bears striking resemblance to results that revealed movement-null vs. movement-potent axes in the arm movement system (Kaufman et al. 2014). The orthogonal encoding scheme would allow pursuit and saccadic eye movement metrics to be decoded separately from a single population of Purkinje cells. This would reduce the computational burden on the cerebellar cortex and may end up being a generalizable principle of cerebellar function that can be investigated across lobules believed to regulate fast and slow movements of other effectors, like the arms.

In agreement with a prior study (Sun et al. 2017), we also observed that the kinematic sensitivity of individual Purkinje cells varies strongly between pursuit and saccadic eye movements. During saccades, simple-spike firing was related mostly to eye position and velocity and during pursuit mostly to eye acceleration and velocity. We conclude that the vermis may contain some context-specific encoding of eye movement metrics. Our findings do differ from previous reports (Dash et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2017) in that the range of sensitivities to especially eye position is considerably narrower in our data. We have no explanation for this difference, although it could be due to the fact that we fitted a longer duration of firing rate that included steady-state pursuit and therefore would constrain the eye position coefficient more strongly.

Different Roles for Oculomotor Vermis and Floccular Complex in Pursuit

The floccular complex has disynaptic access to the extraocular motoneurons and seems to drive the initiation of pursuit and steady-state eye velocity. In contrast, the responses of vermis Purkinje cells suggest that it could play a less direct role in pursuit. Before outlining that role, we summarize the differences in the response of the two structures. First, the directional organization of vermis simple-spike responses is uniform around all directions, unlike the floccular complex where the organization is aligned with the directions of actions of extraocular muscles and semicircular canals (Krauzlis and Lisberger 1996). Second, the responses of vermis Purkinje cells during pursuit are generally weaker than the responses of floccular Purkinje cells, and floccular neurons respond especially strongly in relation to eye acceleration during the initiation of pursuit. Indeed, the responses of vermis Purkinje cells are somewhat stronger during saccades vs. during pursuit. Third, the responses of vermis Purkinje cells are much less predictive on a trial-by-trial basis of the pursuit eye movement compared with floccular Purkinje cells. Fourth, floccular Purkinje cells show a reciprocal direction organization for simple-spike responses and climbing-fiber inputs, while the vermis does not show that relationship. Indeed, this aspect of the responses of vermis Purkinje cells is unexpected given the evidence that climbing-fiber inputs play a causal role in creating the reciprocal relationship (Badura et al. 2013). The absence of the reciprocal relationship makes us suspect that the motor act of initiating smooth pursuit eye movements might not be the critical behavior for the Purkinje cells we have studied. We do not think that our comparison of the two structures is contaminated by the fact that target motions were mainly 20 vs. 30°/s in the vermis vs. the floccular complex. All indications are that the features of floccular responses are very consistent across target speeds and that they scale with the kinematics of eye movement (Medina and Lisberger 2007).

Overall, our results agree qualitatively with historical and contemporary findings about the role of the oculomotor vermis in the control of saccadic eye movements. However, our results also suggest that the role of the vermis in saccades may not generalize to pursuit eye movements. Our physiological findings and conclusions are commensurate with deficits caused by lesions or reversible inactivation of the vermis. The pursuit deficits following vermis lesions are small compared with the deficits following floccular inactivation (Rambold et al. 2002; Robinson et al. 1997; Takagi et al. 2000; 1998). Still, the anatomy of the vermis suggests a large convergence of signals from motor and sensory cortical and subcortical centers traditionally associated with smooth pursuit (Voogd et al. 2012) and seems at odds with the physiology we report.

We suggest two functional explanations for the responses of Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis during pursuit. First, in keeping with the control of saccades by the vermis, we suggest that the vermis may use signals related to pursuit to guide behaviors like catch-up saccades that require integration of information about pursuit eye movements and visual motion (de Brouwer et al. 2002). Second, we ascribe to the idea that the vermis may be more involved in go-nogo decisions about whether to execute pursuit tracking, rather than in driving the moment-by-moment motor behavior or even modulating the strength of visual-motor transmission. Purkinje cells in the vermis seem to be more strongly related to the decision to pursue, and the effects of inactivating the vermis seem to be larger on go-nogo decisions than on basic pursuit (Fukushima et al. 2011; Kurkin et al. 2014).

We find it striking that the floccular complex and the vermis have many similar anatomical connections and yet show quite different functional responses during pursuit eye movement. Both receive mossy-fiber inputs from the dorsolateral pontine nucleus and the nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis (Langer et al. 1985; Yamada and Noda 1987), which presumably relay signals from extrastriate areas MT and MST and the frontal eye field. The floccular complex also receives mossy fiber inputs from the nucleus prepositus and the vestibular nuclei. The two structures receive climbing-fiber inputs from different parts of the inferior olive, visual motion inputs to the floccular complex via the dorsal cap of Kooy vs. signals from the superior colliculus to the vermis via the medial accessory olive (Voogd et al. 2012). The outputs from the two structures also are quite different. Outflow from the floccular complex is relayed disynaptically to the extraocular muscles via the vestibular nucleus (Highstein 1973). Outflow from the vermis may be relayed, via the caudal fastigial nucleus, to brainstem saccade generation circuits that are hypothesized to drive pursuit (Krauzlis 2004). Alternatively it may target unique brainstem nuclei that only drive pursuit (Ugolini et al. 2006). Finally, outflow from the vermis may influence activity in the floccular complex via projections to brainstem relay nuclei (Robinson et al. 1997).

An important limitation of our study, and all studies of the vermis’ role in pursuit comes from the absence of a clear understanding of how the outflow of the vermis interacts with the premotor circuitry that drive pursuit eye movements. Ultimately our results could be interpreted more strongly with the help of a clear understanding of efferent pathways from the oculomotor vermis via the caudal fastigial nucleus.

Role of Oculomotor Vermis in Directional Pursuit Learning

The responses of Purkinje cells in the vermis during and after direction learning in pursuit eye movements were quite different from those in the floccular complex and suggest that the vermis plays little or no role in this form of learning. Simple-spike firing rates barely changed during either on or off learning across our population of neurons, in sharp contrast to prior findings in the floccular complex, and in spite of strong behavioral learning in both animals used for recordings from the vermis. In retrospect, the small learned changes in simple-spike firing might have been expected given the unimpressive climbing-fiber response during learning trials. Climbing-fiber inputs are believed to drive plasticity at the parallel fiber Purkinje cell synapse that regulates the expression of learned oculomotor behaviors (Raymond et al. 1996). The very low probability of climbing-fiber responses in vermis Purkinje cells may not be conducive to driving the learning process. Insofar as direction learning occurs in the vermis during pursuit, it might be mediated by the myriad other plasticity mechanisms that exist in the cerebellar circuit (Carey 2011; Gao et al. 2012; Hansel et al. 2001). We recognize some potential weaknesses in our learning experiments, but we do not think those minor weaknesses contradict our view that the vermis plays a much weaker role than does the floccular complex in pursuit direction learning. Because of the challenges of recognizing the preferred direction for complex spikes during the experiment, we might not have chosen optimal learning directions. We might have found more impressive neural learning if our experiments had been set up to take better advantage of an individual neuron’s complex-spike tuning curve. We also recognize that the responses of vermis Purkinje cells during pursuit are weak compared with those in the floccular complex, and this alone might reduce the chance of observing neural learning. In any event, our data imply that the floccular complex plays a clearer and more immediate role in direction learning in pursuit. Interestingly, the changes in simple-spike responses of vermis Purkinje cells during speed learning seem to be larger than what we found for directional learning (Dash et al. 2013) and lesions of the vermis strongly impact speed adaptation (Takagi et al. 2000). Thus the vermis may play a larger role in speed learning, a situation that would fit well with the demonstrated role of the oculomotor vermis in learning the amplitude of saccades (Kojima et al. 2010; Soetedjo and Fuchs 2006; Soetedjo et al. 2008).

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS-092623.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.T.R. and S.G.L. conceived and designed research; R.T.R. performed experiments; R.T.R. analyzed data; R.T.R. and S.G.L. interpreted results of experiments; R.T.R. and S.G.L. prepared figures; R.T.R. drafted manuscript; R.T.R. and S.G.L. edited and revised manuscript; R.T.R. and S.G.L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stefanie Tokiyama for technical assistance, Steven Happel for information technology services, and many members of the Duke Neurobiology community for helpful discussions and encouragement. We thank Javier Medina for allowing reanalysis of previously published data. Yoshiko Kojima and Robijanto Soetedjo at the University of Washington provided important advice and training for recording from the oculomotor vermis.

REFERENCES

- Badura A, Schonewille M, Voges K, Galliano E, Renier N, Gao Z, Witter L, Hoebeek FE, Chédotal A, De Zeeuw CI. Climbing fiber input shapes reciprocity of Purkinje cell firing. Neuron 78: 700–713, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berens P. CircStat: a MATLAB toolbox for circular statistics. J Stat Softw 31: 1–21, 2009. doi: 10.18637/jss.v031.i10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MR. Synaptic mechanisms of sensorimotor learning in the cerebellum. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21: 609–615, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchland MM, Cunningham JP, Kaufman MT, Ryu SI, Shenoy KV. Cortical preparatory activity: representation of movement or first cog in a dynamical machine? Neuron 68: 387–400, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash S, Catz N, Dicke PW, Thier P. Encoding of smooth-pursuit eye movement initiation by a population of vermal Purkinje cells. Cereb Cortex 22: 877–891, 2012. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash S, Dicke PW, Thier P. A vermal Purkinje cell simple spike population response encodes the changes in eye movement kinematics due to smooth pursuit adaptation. Front Syst Neurosci 7: 3, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2013.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brouwer S, Yuksel D, Blohm G, Missal M, Lefèvre P. What triggers catch-up saccades during visual tracking? J Neurophysiol 87: 1646–1650, 2002. doi: 10.1152/jn.00432.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher NI. Statistical Analysis of Circular Data. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511564345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima K, Fukushima J, Kaneko CR, Belton T, Ito N, Olley PM, Warabi T. Memory-based smooth pursuit: neuronal mechanisms and preliminary results of clinical application. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1233: 117–126, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima K, Fukushima J, Kaneko CR, Fuchs AF. Vertical Purkinje cells of the monkey floccular lobe: simple-spike activity during pursuit and passive whole body rotation. J Neurophysiol 82: 787–803, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, van Beugen BJ, De Zeeuw CI. Distributed synergistic plasticity and cerebellar learning. Nat Rev Neurosci 13: 619–635, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nrn3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel C, Linden DJ, D’Angelo E. Beyond parallel fiber LTD: the diversity of synaptic and non-synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum. Nat Neurosci 4: 467–475, 2001. doi: 10.1038/87419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzfeld DJ, Kojima Y, Soetedjo R, Shadmehr R. Encoding of action by the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. Nature 526: 439–442, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nature15693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highstein SM. Synaptic linkage in the vestibulo-ocular and cerebello-vestibular pathways to the VIth nucleus in the rabbit. Exp Brain Res 17: 301–314, 1973. doi: 10.1007/BF00234668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohl SS, Chaisanguanthum KS, Lisberger SG. Sensory population decoding for visually guided movements. Neuron 79: 167–179, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Negrello M, Junker M, Smilgin A, Thier P, De Schutter E. Multiplexed coding by cerebellar Purkinje neurons. eLife 5: e13810, 2016. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshua M, Lisberger SG. A framework for using signal, noise, and variation to determine whether the brain controls movement synergies or single muscles. J Neurophysiol 111: 733–745, 2014. doi: 10.1152/jn.00510.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MT, Churchland MM, Ryu SI, Shenoy KV. Cortical activity in the null space: permitting preparation without movement. Nat Neurosci 17: 440–448, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nn.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima Y, Soetedjo R, Fuchs AF. Changes in simple spike activity of some Purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis during saccade adaptation are appropriate to participate in motor learning. J Neurosci 30: 3715–3727, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4953-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauzlis RJ. Recasting the smooth pursuit eye movement system. J Neurophysiol 91: 591–603, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.00801.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauzlis RJ, Lisberger SG. Directional organization of eye movement and visual signals in the floccular lobe of the monkey cerebellum. Exp Brain Res 109: 289–302, 1996. doi: 10.1007/BF00231788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauzlis RJ, Miles FA. Role of the oculomotor vermis in generating pursuit and saccades: effects of microstimulation. J Neurophysiol 80: 2046–2062, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurkin S, Akao T, Fukushima J, Shichinohe N, Kaneko CR, Belton T, Fukushima K. No-go neurons in the cerebellar oculomotor vermis and caudal fastigial nuclei: planning tracking eye movements. Exp Brain Res 232: 191–210, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00221-013-3731-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer T, Fuchs AF, Scudder CA, Chubb MC. Afferents to the flocculus of the cerebellum in the rhesus macaque as revealed by retrograde transport of horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol 235: 1–25, 1985. doi: 10.1002/cne.902350102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Lisberger SG. Gamma synchrony predicts neuron-neuron correlations and correlations with motor behavior in extrastriate visual area MT. J Neurosci 33: 19677–19688, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3478-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisberger SG. Visual guidance of smooth-pursuit eye movements: sensation, action, and what happens in between. Neuron 66: 477–491, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisberger SG, Pavelko TA. Vestibular signals carried by pathways subserving plasticity of the vestibulo-ocular reflex in monkeys. J Neurosci 6: 346–354, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina JF, Carey MR, Lisberger SG. The representation of time for motor learning. Neuron 45: 157–167, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina JF, Lisberger SG. Variation, signal, and noise in cerebellar sensory-motor processing for smooth-pursuit eye movements. J Neurosci 27: 6832–6842, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1323-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina JF, Lisberger SG. Links from complex spikes to local plasticity and motor learning in the cerebellum of awake-behaving monkeys. Nat Neurosci 11: 1185–1192, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nn.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina JF, Lisberger SG. Encoding and decoding of learned smooth-pursuit eye movements in the floccular complex of the monkey cerebellum. J Neurophysiol 102: 2039–2054, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.00075.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H, Fujikado T. Topography of the oculomotor area of the cerebellar vermis in macaques as determined by microstimulation. J Neurophysiol 58: 359–378, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne LC, Lisberger SG, Bialek W. A sensory source for motor variation. Nature 437: 412–416, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nature03961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Lisberger SG. Normal performance and expression of learning in the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) at high frequencies. J Neurophysiol 93: 2028–2038, 2005. doi: 10.1152/jn.00832.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambold H, Churchland A, Selig Y, Jasmin L, Lisberger SG. Partial ablations of the flocculus and ventral paraflocculus in monkeys cause linked deficits in smooth pursuit eye movements and adaptive modification of the VOR. J Neurophysiol 87: 912–924, 2002. doi: 10.1152/jn.00768.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashbass C. The relationship between saccadic and smooth tracking eye movements. J Physiol 159: 326–338, 1961. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JL, Lisberger SG, Mauk MD. The cerebellum: a neuronal learning machine? Science 272: 1126–1131, 1996. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson FR, Fuchs AF. The role of the cerebellum in voluntary eye movements. Annu Rev Neurosci 24: 981–1004, 2001. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson FR, Straube A, Fuchs AF. Role of the caudal fastigial nucleus in saccade generation. II. Effects of muscimol inactivation. J Neurophysiol 70: 1741–1758, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson FR, Straube A, Fuchs AF. Participation of caudal fastigial nucleus in smooth pursuit eye movements. II. Effects of muscimol inactivation. J Neurophysiol 78: 848–859, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Noda H. Posterior vermal Purkinje cells in macaques responding during saccades, smooth pursuit, chair rotation and/or optokinetic stimulation. Neurosci Res 12: 583–595, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(92)90065-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppik D, Nagel KI, Lisberger SG. Cortical mechanisms of smooth eye movements revealed by dynamic covariations of neural and behavioral responses. Neuron 58: 248–260, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shidara M, Kawano K, Gomi H, Kawato M. Inverse-dynamics model eye movement control by Purkinje cells in the cerebellum. Nature 365: 50–52, 1993. doi: 10.1038/365050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soetedjo R, Fuchs AF. Complex spike activity of purkinje cells in the oculomotor vermis during behavioral adaptation of monkey saccades. J Neurosci 26: 7741–7755, 2006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4658-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soetedjo R, Kojima Y, Fuchs AF. Complex spike activity in the oculomotor vermis of the cerebellum: a vectorial error signal for saccade motor learning? J Neurophysiol 100: 1949–1966, 2008. doi: 10.1152/jn.90526.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LS, Lisberger SG. Visual responses of Purkinje cells in the cerebellar flocculus during smooth-pursuit eye movements in monkeys. II. Complex spikes. J Neurophysiol 63: 1262–1275, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Smilgin A, Junker M, Dicke PW, Thier P. The same oculomotor vermal Purkinje cells encode the different kinematics of saccades and of smooth pursuit eye movements. Sci Rep 7: 40613, 2017. doi: 10.1038/srep40613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki DA, Noda H, Kase M. Visual and pursuit eye movement-related activity in posterior vermis of monkey cerebellum. J Neurophysiol 46: 1120–1139, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]