Feature at a glance

Designing innovations aligned with patients’ needs and workflow requires human factors and ergonomics (HF/E) fieldwork in home and community settings. Fieldwork in these extra-institutional settings is challenged by a need to balance the occasionally competing priorities of patient and informal caregiver participants, study team members, and the overall project. We offer several strategies that HF/E professionals can use before, during, and after home and community site visits to optimize fieldwork and mitigate challenges in these settings. Strategies include interacting respectfully with participants, documenting the visit, managing the study team-participant relationship, and engaging in dialogue with institutional review boards.

Keywords: Fieldwork, patients, informal caregivers, extra-institutional settings, work systems, health information technology

Short Feature

Health care HF/E: moving into the home and community

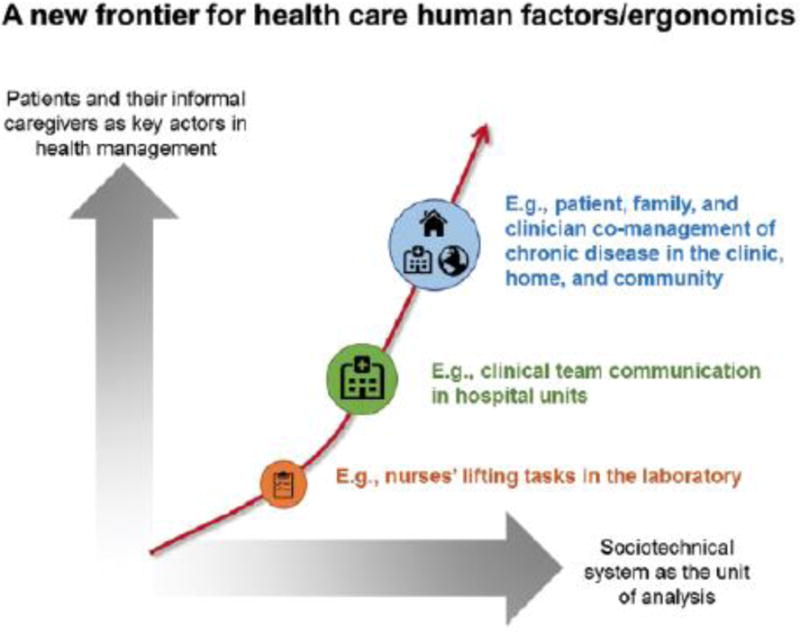

Human factors/ergonomics (HF/E) has contributed to improving health care for over half a century (Chapanis & Safrin, 1960) and is increasingly recognized as a key driver for advances in health care quality and safety (Institute of Medicine, 2011; National Academy of Engineering & Institute Medicine, 2005). Meaningful contributions in the future will be stimulated by two paradigm shifts, which are transforming the targets and settings of health care HF/E practice and research. The first shift concerns the unit of analysis. In HF/E, the focus has extended from physical to cognitive to sociotechnical systems (Holden, Rivera, & Carayon, 2015). In health care, the focus has similarly progressed from biomedical to psychological to systems approaches (Valdez, Holden, Novak, & Veinot, 2015). Consequently, it is increasingly recognized that health care HF/E intervention design, whether technological or programmatic, must account for physical, organizational, and social environments that comprise the larger system context (Waterson, 2009). The second paradigm shift concerns the scope of health care. While HF/E practice within health care originated within institutional settings such as hospitals and clinics (Chapanis & Safrin, 1960), it is increasingly acknowledged as also encompassing home and community settings (e.g., self-regulating blood glucose, managing health information) (Holden, Schubert, & Mickelson, 2015; Moen & Brennan, 2005; Zayas-Caban & Valdez, 2011). This transition is the result of multiple trends, including increased fragmentation of care, insurance based pressures for earlier discharge, proliferation of health information technology, and cultural shifts emphasizing patient engagement and shared decision-making (Brennan, Downs, and Casper, 2010; Carman et al., 2013; Gruman et al., 2010). To be responsive to this shift of scope, HF/E interventions must not only consider professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses, therapists) but also patients, family members, friends, and others in their community. The intersection of these two paradigm shifts implies that a new frontier for HF/E in health care is a sociotechnical systems approach that considers health care as a system including the home and community (Figure 1). Such an approach is relevant for studying and developing interventions to address a range of phenomena including transitions of care, chronic illness management, care coordination, and health information technology (Carayon et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Progression of human factors/ergonomics research in health care.

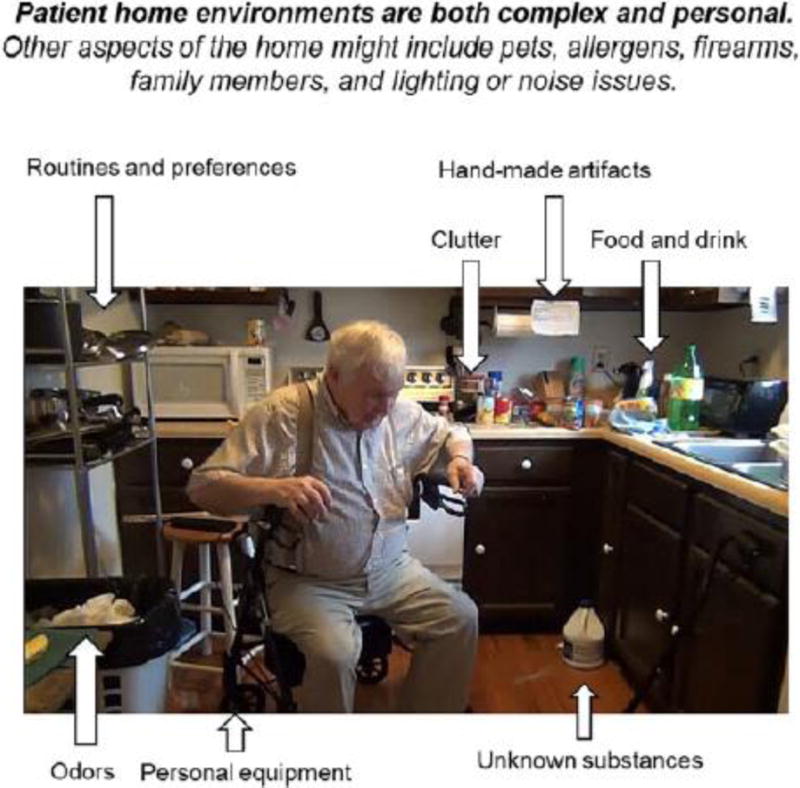

Existing HF/E tools and concepts relevant to a sociotechnical systems approach require adaptation to be effectively applied to home and community settings. In comparison to hospital and clinic environments, patients’ homes and communities are highly personal spaces in which health care activities are enmeshed with many other activities of daily living (Corbin & Strauss, 1985) (Figure 2). Moreover, unlike health care professionals, patients and the individuals that support them are not typically paid to engage in health-related work. Work system models have been developed that specifically attend to health-related work in extra-institutional settings (Holden et al., 2013; National Research Council, 2011). Similarly, efforts are underway to translate the concept of workload for the patient context (Nathan-Roberts, Holden, Yin, & Valdez, 2015). In addition to theoretical and methodological considerations, home and community environments raise unique challenges for initiating and conducting fieldwork (Furniss et al., 2014; Holden, Scott, Hoonakker, Hundt, & Carayon, 2014).

Figure 2.

Characteristics of patients’ home environments.

The HF/E community is amassing experience within home and community environments through projects spanning health care phenomena (e.g., care coordination, self-monitoring, personal health information management), patient diagnoses (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, Type 2 diabetes), and designs (e.g., qualitative inquiry, clinical trials). These experiences illuminate the challenges and competing priorities that must be managed during fieldwork. Moreover, the lessons learned inform best practices for health care HF/E professionals to follow when interacting in this space.

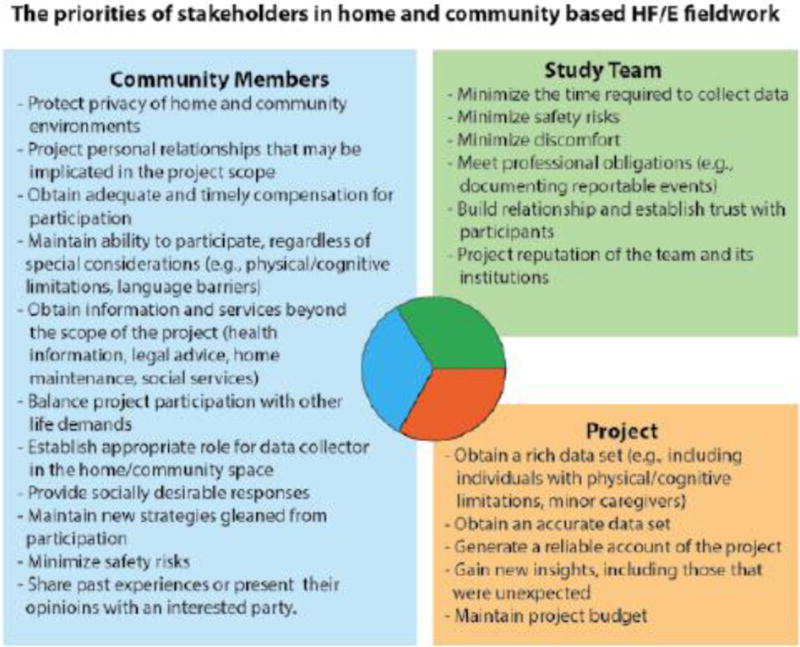

Challenges and competing priorities: the community, the study team, and the project

There are multiple stakeholders whose priorities must be adequately addressed to successfully complete fieldwork in the home and community. The three primary stakeholders are: 1) community members, or the patients and informal caregivers whose activities and environments are the focus of inquiry, 2) study team members, or the HF/E professionals who are conducting the investigation, and 3) the project, which although not an independent stakeholder, has specific goals associated with its integrity and may be represented by a client or funder. Figure 3 details the priorities of each stakeholder. The challenge is balancing these priorities, which may conflict. Two brief examples are provided below:

Javier leads a new project to develop an app for asthma management at home. The project has a short turnaround time; thus, the team has limited time to devote to fieldwork. During a visit with a key community partner, Javier is taken by surprise when he discovers the individual has low literacy and asks for assistance with using the app. Javier is concerned about the amount of time this interaction will take, although he realizes that obtaining data from individuals with low literacy may provide unique insights, improving his product’s quality.

Rachel investigates how social and physical environments impact the effectiveness of care coordination (i.e., organization of patient care activities and information sharing among all individuals involved in a patient’s care). Her methods include interviews and still photography of the physical environment. During a home visit, a participant offers to show the challenge of storing medical equipment in a basement closet. Rachel is unsure how to proceed. The project would benefit from the photographs and Rachel is wary of offending or diminishing the participant’s trust, but feels that venturing into a space far from an exit compromises her personal safety.

Figure 3.

The priorities of stakeholders in home- and community-based human factors/ergonomics fieldwork.

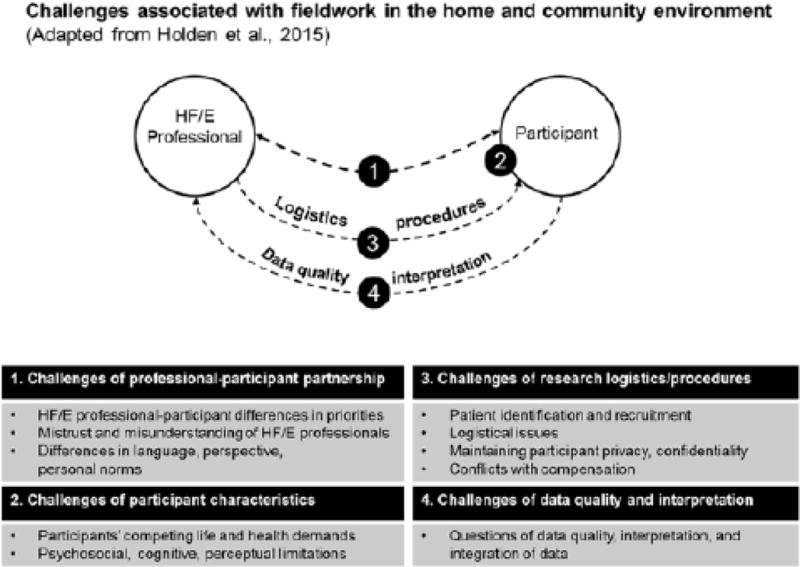

These cases illustrate only some of the challenges encountered in fieldwork. Many other examples are presented by Holden and colleagues (2015), who developed a framework of challenges encountered in home and community based health care HF/E fieldwork, including difficulties gaining trust from participants, problems interacting with sick or impaired patients, confidentiality and compensation challenges, and questions of data quality (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Challenges associated with fieldwork in the home and community environment. [Adapted from Holden, Scott, Hoonakker, Hundt, & Carayon, 2015]

Best practices: strategies for health care HF/E fieldwork in the home and community

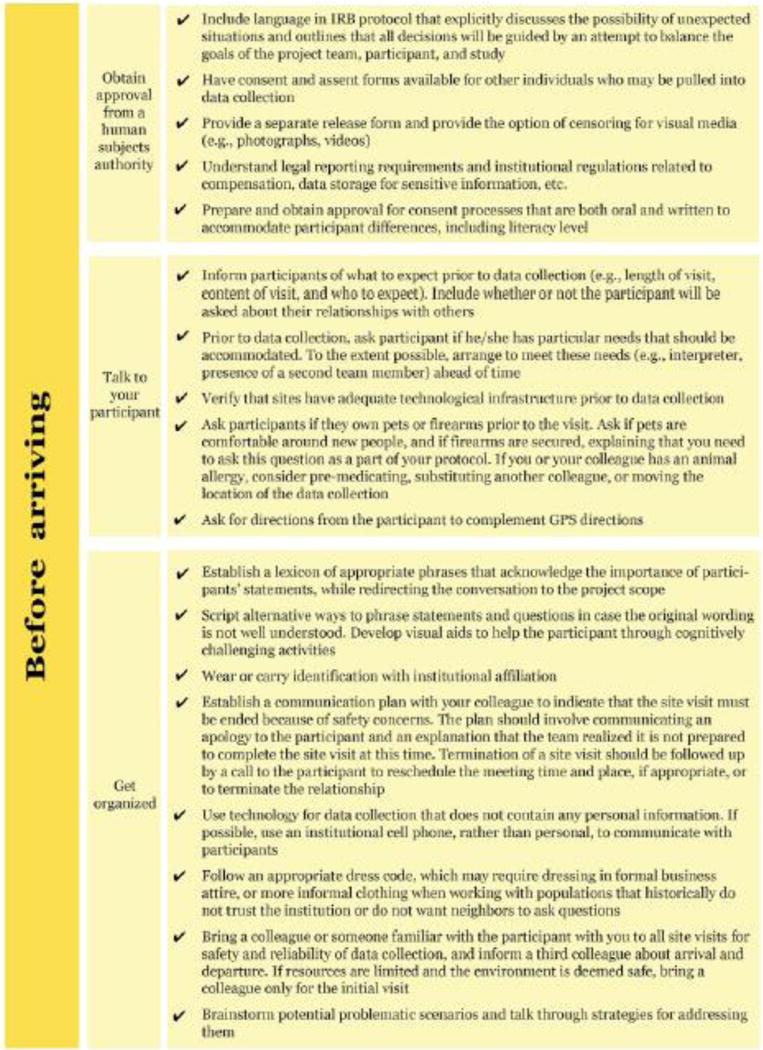

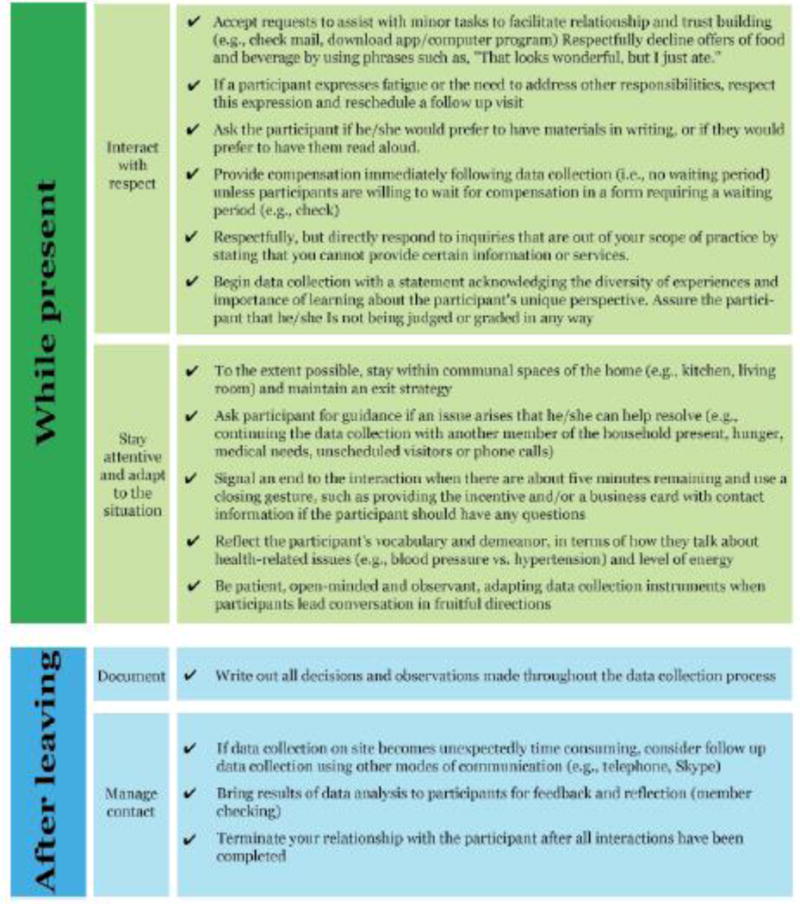

To address these challenges and competing priorities, best practices for health care HF/E fieldwork in the home and community should be used before, during, and after a site visit. Prior to visiting a participant in an extra-institutional setting, assess potential challenges related to the legal and ethical implications of their interaction with human subjects, develop contingency plans, and obtain the necessary approval from an institutional human subjects authority. Establish contact with the participant to plan the logistical aspects of the visit. In collaboration with other members of the study team, determine how situations compromising safety and miscommunication would be addressed. During the site visit, demonstrate respect for the participant while simultaneously protecting personal safety and staying within the scope of HF/E expertise. Also, be alert and flexible in responding to unexpected situations. After leaving the site visit, immediately document the experience, paying particular attention to unusual events and unique insights. Finally, before formally ending a relationship with a participant, extend the interactions as necessary to complete the study rigorously. Figure 5 provides a checklist of specific strategies that may be implemented when conducting health care HF/E fieldwork in the home and community.

Figure 5.

Health care human factors/ergonomics home and community fieldwork checklist.

Examples of strategies that could be used to address Javier and Rachel’s challenges are provided below:

Javier may have been better prepared for a low-literacy participant if he had contacted the participant prior to the site visit and asked about special needs requiring accommodation. With this information, he could have obtained permission from his institution’s human subjects authority to use an oral consent process and to provide assistance with app usage. Even if he had not followed the recommendations above, with an established protocol for managing unexpected situations, Javier would have been able to comfortably ask the participant to reschedule the meeting to give himself time to address these matters.

Rachel would have been better prepared to handle the invitation to visit a participant’s basement if she were accompanied by another team member and had informed a third team member of her whereabouts. With two people at the site visit and a communication plan for relaying safety concerns, Rachel would have been more comfortable taking the requested photographs. In her fieldwork protocol, Rachel should also have committed to maintaining constant access to an exit. Despite these precautions, Rachel may still have had concerns about entering the basement, in which case she should have prepared phrases to respectfully decline this or other discomforting offers. For example, Rachel could have said, “Your example would be really useful for the study, but unfortunately I am running low on time today. Could we perhaps schedule another time to take the photograph?” or, “My supervisor does not allow me to enter people’s basements, out of concern for safety.”

The strategies we have recommended are grounded in our experience conducting health care HF/E fieldwork in home and community settings and the guidance provided to us by the institutional review boards at the institutions with which we have been affiliated. For individuals whose activities in the home and community are overseen by an IRB, we recommend having a discussion about the specific protocol you intend to implement. In our own experiences we have encountered conflicting advice about the types of information that may be requested from or about potential participants prior to informed consent, the degree to which an interaction must be scripted, and how to determine study eligibility for individuals whose roles overlap (e.g., patient and caregiver). Building flexibility into the protocol is also advisable. For example, in Rachel’s scenario the participant may have asked if he could take the picture and send it to her securely. If this form of data collection was written into the protocol, Rachel could have obtained the photographs without compromising her safety or inconveniencing the participant with a second visit.

Conclusion

HF/E professionals working in health care are committed to designing innovations aligned with patients’ needs and preferences. Laboratory-based assessments are limited in that they primarily facilitate an understanding of interactions between the user, the task, and the technology. Designing systems that are also responsive to patients’ social, organizational, and physical environments requires assessing needs and preferences in the home and community, as well. However, fieldwork in extra-institutional settings is challenging and requires balancing the priorities of multiple stakeholders. By articulating strategies to address these challenges and competing priorities, we aim to provide a foundation for best practices for health care HF/E fieldwork in the home and community. Future work is needed to address the many challenges that arise from conducting fieldwork in this new domain, such as translating an abundance of field data into concrete design recommendations (Valdez, Holden, Novak, and Veinot, 2015). and adapting HF/E paradigms for systems-oriented assessments of home and community-based health care.

Acknowledgments

RSV was supported by grants R36 HS 018809-01 and 1 R03 HS022930-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). RJH is supported by grant K01AG044439 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of AHRQ or NIH. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Patti Brennan, Pascale Carayon, Peter Hoonakker, Ann Hundt, Jenna Marquard, Enid Montague, Calvin Or, Dan Nathan-Roberts, Teresa Zayas-Caban, and all community partners and study participants.

Biographies

Rupa Valdez is assistant professor of biomedical informatics at the University of Virginia. She received her PhD in industrial and systems engineering from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2012. Her research draws on methods from human factors, medical informatics, population health, and cultural anthropology to conduct home and community fieldwork for the purpose of guiding and evaluating consumer health information technology design. She may be reached at rupa.valdez@virginia.edu.

Richard Holden is assistant professor of BioHealth Informatics at the Indiana University School of Informatics and Computing, Indianapolis. He received a joint PhD in industrial engineering and psychology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2009. His research applies human factors to study and improve the work performance of patients, informal caregivers, and clinicians. He has investigated multiple healthcare interventions, including information technology, team-based care, and lean process redesign. He may be reached at rjholden@iupui.edu.

References

- Brennan PF, Downs S, Casper G. Project HealthDesign: rethinking the power and potential of personal health records. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2010;43(5 Suppl):S3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Karsh BT, Gurses A, Holden R, Hoonakker P, Hundt AS, Wetterneck TB. Macroergonomics in healthcare quality and patient safety. Review of Human Factors and Ergonomics. 2013;8(1):4–54. doi: 10.1177/1557234X13492976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, Sweeney J. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapanis A, Safrin MA. Of misses and medicines. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1960;12(4):403–408. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(60)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss AL. Managing chronic illness at home: three lines of work. Qualitative Sociology. 1985;8(3):224–247. [Google Scholar]

- Furniss D, O’Kane A, Randell R, Taneva S, Mentis H, Blandford A. Fieldwork for Healthcare: Case Studies Investigating Human Factors in Computing Systems. Morgan & Claypool 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Gruman J, Rovner MH, French ME, Jeffress D, Sofaer S, Shaller D, Prager DJ. From patient education to patient engagement: implications for the field of patient education. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;78(3):350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, Rivera AJ, Carayon P. Occupational macroergonomics: principles, scope, value, and methods. IIE Transactions on Occupational Ergonomics and Human Factors. 2015 doi: 10.1080/21577323.2015.1027638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, Scott AMM, Hoonakker PLT, Hundt AS, Carayon P. Data collection challenges in community settings: insights from two field studies of patients with chronic disease. Quality of Life Research. 2014;24(5):1043–55. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0780-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, Schubert CC, Mickelson RS. The patient work system: An analysis of self-care performance barriers among elderly heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. Applied Ergonomics. 2015;47:133–150. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, Hoonakker P, Hundt AS, Ozok AA, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ. SEIPS 2.0. A human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics. 2013;56(11):1669–1686. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2013.838643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Health IT and Patient Safety: Building Safer Systems for Better Care. 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen A, Brennan PF. Health@Home: the work of health information management in the household (HIMH): implications for consumer health informatics (CHI) innovations. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2005;12(6):648–656. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan-Roberts D, Holden RJ, Yin S, Valdez RS. Examining patient work: the when, and how much of self-care. Paper to be presented at the 19th Triennial Congress of the International Ergonomics Association Melbourne; Australia. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Engineering, & Institute of Medicine. Building a Better Delivery System: A New Engineering/Health Care Partnership 2005 [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Health Care Comes Home: The Human Factors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez RS, Holden RJ, Novak LL, Veinot TC. Transforming consumer health informatics through a patient work framework: connecting patients to context. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2015;22(1):2–10. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterson P. A critical review of the systems approach within patient safety research. Ergonomics. 2009;52(10):1185–1195. doi: 10.1080/00140130903042782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas-Caban T, Valdez RS. Human factors in home care. In: Carayon P, editor. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2011. [Google Scholar]