Abstract

Objective:

To implement a mendelian randomization (MR) approach to determine whether type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and body mass index (BMI) are causally associated with specific ischemic stroke subtypes.

Methods:

MR estimates of the association between each possible risk factor and ischemic stroke subtypes were calculated with inverse-variance weighted (conventional) and weighted median approaches, and MR-Egger regression was used to explore pleiotropy. The number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) used as instrumental variables was 49 for T2D, 36 for fasting glucose, 18 for fasting insulin, and 77 for BMI. Genome-wide association study data of SNP-stroke associations were derived from METASTROKE and the Stroke Genetics Network (n = 18,476 ischemic stroke cases and 37,296 controls).

Results:

Conventional MR analysis showed associations between genetically predicted T2D and large artery stroke (odds ratio [OR] 1.28, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.16–1.40, p = 3.3 × 10−7) and small vessel stroke (OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.10–1.33, p = 8.9 × 10−5) but not cardioembolic stroke (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.97–1.15, p = 0.17). The association of T2D with large artery stroke but not small vessel stroke was consistent in a sensitivity analysis using the weighted median method, and there was no evidence of pleiotropy. Genetically predicted fasting glucose and fasting insulin levels and BMI were not statistically significantly associated with any ischemic stroke subtype.

Conclusions:

This study provides support that T2D may be causally associated with large artery stroke.

Stroke is one of the leading causes of disability and death worldwide.1 The burden of stroke is projected to increase considerably in the next decades. Hence, there is a need to develop effective prevention strategies for stroke, which necessitates a better understanding of the underlying risk factors. About 80% of all strokes are ischemic,1 but this term describes a syndrome caused by a number of different pathologies, which may have different treatments.2 The major etiologies of ischemic stroke are large artery atherosclerosis (large artery stroke), small vessel atherosclerosis (small vessel stroke), and cardioembolism (cardioembolic stroke). Recent data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have shown that these subtypes have distinctive risk factor profiles and, by implication, diverse pathophysiologic bases.3

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke,4 but its relative contribution to different ischemic stroke subtypes is unknown. Moreover, several risk factors that are highly correlated with T2D, including hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and body mass index (BMI), have been associated with risk of stroke in observational studies.5,6 However, the causality of the association between these metabolic factors and stroke risk is uncertain because of the high correlations between these factors, and the associations may be confounded by an unhealthy diet or other behavioral or environmental risk factors. Whether elevated fasting glucose and insulin levels and BMI have different associations with different ischemic stroke subtypes is unknown.

The technique of mendelian randomization (MR) is increasingly being used to examine causality of associations between modifiable risk factors and various diseases, particularly when confounding is of concern. It uses genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs]) as instrumental variables for estimating the effect of a risk factor on a disease risk. Because genotypes are randomly allocated during meiosis, the population genotype distribution should be unrelated to any confounders.7 In this respect, MR can be thought of as a natural randomized controlled trial. In the present study, MR was implemented to determine whether T2D, glucose, insulin, and BMI are causally associated with all ischemic stroke and with its 3 main subtypes: large artery, small vessel, and cardioembolic stroke.

METHODS

Study design and data sources.

This MR analysis was conducted with summary statistics from 2 large ischemic stroke genetics consortia: the METASTROKE Collaboration3,8 and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)–Stroke Genetics Network (SiGN).9 GWAS from these consortia contributed a total of 18,476 ischemic stroke cases and 37,296 controls of mainly European ancestry. Overlapping participants in the 2 consortia were removed. The Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification system was used for stroke subtyping,10 identifying 2,947 large artery strokes, 2,757 small vessel strokes, and 3,860 cardioembolic strokes. In addition, there were 8,912 undetermined strokes (cases in which the stroke mechanism had not been identified) and multiple-pathologies strokes. All cases were ischemic stroke and had brain imaging to confirm this and to exclude a hemorrhage. The majority of stroke cases were prevalent cases. Genotyping was performed with a variety of Illumina or Affymetrix platforms. All cohorts underwent genotype imputation with the 1000 Genomes (1KG) phase I reference panel before meta-analysis.8,11 Data from NINDS-SiGN were imputed to a merged reference panel that included the 1KG project phase I and Genome of the Netherlands.12

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Each study included in the stroke consortia was approved by an Institutional Review Board, and all patients provided informed consent.

SNP selection.

We selected all SNPs associated with T2D,13–16 fasting glucose,17 fasting insulin,17 and BMI18 at a genome-wide significance threshold (p < 5 × 10−8) in individuals of European ancestry in previously published large-scale GWAS. Because the effects of FTO variants on T2D and fasting insulin appear to be mediated solely by BMI,17 SNPs from this locus were excluded from the analyses of T2D and fasting insulin to avoid possible confounding by BMI. Thus, the number of SNPs used as instrumental variables in the present analyses was 49 for T2D, 36 for fasting glucose, 18 for fasting insulin, and 77 for BMI (i.e., SNPs associated with BMI in the primary meta-analysis of European-descent individuals) (table e-1 at Neurology.org). All SNPs within each trait were uncorrelated (not in linkage disequilibrium).

Statistical analysis.

Summary statistics for the association of each SNP with the risk factors and ischemic stroke as a whole and the 3 main subtypes (large artery, small vessel, and cardioembolic strokes) were acquired from previously published GWAS of the risk factors13–18 and 2 stroke consortia (METASTROKE and NINDS-SiGN) , respectively.8,9 The SNP–risk factor and SNP-stroke associations were used to compute estimates of each risk factor–stroke association using an inverse-variance weighted method19 (hereafter referred to as conventional MR analysis). We conducted complementary analyses using the weighted median and MR-Egger regression methods.20,21 MR-Egger regression can identify and control for bias due to directional pleiotropy (i.e., when the pleiotropic effects of genetic variants are not balanced about the null).20 In sensitivity analyses, we assessed the robustness of the results by excluding loci that overlapped between the 4 metabolic traits assessed in this study and by excluding SNPs associated with blood lipids22,23 and smoking24 (table e-1).

Results of the MR analyses are presented per genetically predicted 1-unit-higher log-odds of T2D and 1-SD increase in fasting glucose (0.65 mmol/L) and natural log-transformed fasting insulin (0.60 pmol/L). The SDs used for scaling of the results for glucose and insulin were derived from the population-based Fenland25 and Ely26 studies. Because the GWAS of BMI estimated the SNP-BMI associations using inverse normal transformation, the MR estimates can be interpreted as the odds ratio (OR) per 1-SD increment in BMI. All statistical tests were 2 sided and considered statistically significant at Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold (p = 0.05/16 tests = 0.003). The analyses were performed in Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

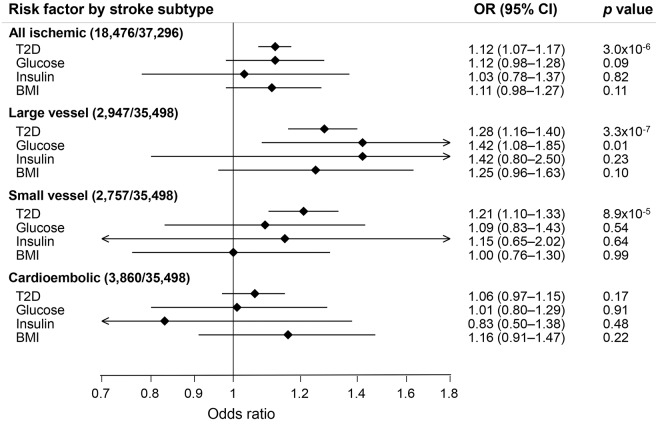

The associations between each genetically predicted risk factor and all ischemic strokes and ischemic stroke subtypes using conventional MR analysis are presented in the figure. T2D was associated with a higher odds of all ischemic stroke (OR 1.12, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–1.17, p = 3.0 × 10−6), large artery stroke (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.16–1.40, p = 3.3 × 10−7), and small vessel stroke (OR 1.21;, 95% CI 1.10–1.33, p = 8.9 × 10−5) but not with cardioembolic stroke (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.97–1.15, p = 0.17). The association of T2D with large artery stroke but not small vessel stroke was consistent in complementary analysis using the weighted median method (table e-2). Results from the MR-Egger regression analysis, which has lower statistical power, yielded a similar OR for T2D and large artery stroke, but the CI was wide and included the null (table e-2). MR-Egger regression analysis provided no evidence of directional pleiotropy for the associations of T2D with large artery stroke (intercept = 0.003, p = 0.82), small vessel stroke (intercept = 0.008, p = 0.50), or cardioembolic stroke (intercept = 0.005, p = 0.62).

Figure. Mendelian randomization estimates of the association between each genetically predicted risk factor and ischemic stroke and its subtypes.

Analyses were performed with conventional mendelian randomization analysis (inverse-variance weighted method). The scaling of the ORs was 1-unit-higher log-odds for T2D and 1-SD increase for fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and BMI. Number of cases/controls is given in parentheses. BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; T2D = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Genetically predicted higher fasting glucose was associated with a higher odds of large artery stroke in conventional MR analysis (figure), but the result did not remain statistically significant after Bonferroni correction, and no statistically significant association was observed in the weighted median and MR-Egger regression analyses (table e-2). A similar, nonsignificant association was found between fasting insulin and large artery stroke (figure and table e-2). Fasting glucose and fasting insulin were not associated with small vessel or cardioembolic strokes, and there were no associations between BMI and all ischemic strokes or any subtype (figure and table e-2).

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the results (table e-3). First, we excluded the TCF7L2 locus, which was associated with large artery stroke, as well as strongly associated with T2D and weakly with the other 3 traits (table e-1). Exclusion of this locus did not appreciably change the results for T2D and large artery stroke (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.13–1.39, p = 3.3 × 10−5). Removing loci that overlapped between the 4 traits also did not materially alter the results for T2D and large artery stroke (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.14–1.53, p = 2.5 × 10−4) or any of the other findings (table e-3). In a further sensitivity analysis, we excluded SNPs associated with lipids (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, or triglycerides) at the genome-wide significance level. In this analysis, the association between T2D and large artery stroke remained (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.17–1.42, p = 6.0 × 10−7), and the associations of the other 3 traits with ischemic stroke did not change appreciably (table e-3). Finally, the lack of association between BMI and all ischemic stroke and its subtypes remained after the removal of the BDNF locus, which has been found to be associated with smoking (table e-3).

DISCUSSION

This MR study showed a robust association between genetic predisposition to T2D and large artery stroke but not small vessel or cardioembolic stroke. It did not provide clear evidence for a causal role of fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and BMI in any ischemic stroke subtype.

Studies of the association between T2D and etiologic subtypes of ischemic stroke are rare, but several previous observational studies have investigated the association between T2D and risk of all ischemic strokes or total stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes combined). For example, in a prospective cohort of 1.9 million people, T2D was associated with a 72% increased risk of all ischemic strokes.4 Furthermore, in a meta-analysis of 64 observational prospective studies, representing 775,385 individuals and 12,539 stroke cases, the overall relative risks of total stroke for individuals with diabetes vs nondiabetics were 2.28 (95% CI 1.93–2.69) in women and 1.83 (95% CI 1.60–2.08) in men.27

T2D is associated with insulin resistance and elevated insulin levels during the early stages of the disease. Eventually, the pancreas is no longer able to compensate the insulin resistance by secreting sufficient insulin to keep the blood glucose level within the normal range, thereby resulting in hyperglycemia. A meta-analysis of 14 prospective studies reported a statistically significant 44% increased risk of total stroke for high vs low fasting glucose levels.6 Insulin resistance was associated with a 76% increased risk of stroke (based on 4 studies), and high vs low fasting insulin was associated with a nonsignificant 90% higher risk (based on 2 studies).6

The value of intensive glucose-lowering therapy for cardiovascular disease prevention in patients with T2D was questioned when 2 randomized controlled trials failed to show a reduction in major vascular events, including stroke,28,29 and even increased mortality29 with the use of intensive glucose control compared with standard therapy. The present MR study found no clear support for a causal role of fasting glucose in any ischemic stroke subtype. Genetically predicted fasting glucose was associated with large artery stroke at nominal statistical significance in the conventional MR analysis, but this association did not remain in the MR-Egger regression analysis.

A randomized controlled trial that investigated the effect of pioglitazone, which improves insulin sensitivity, on cardiovascular events in patients with insulin resistance but without T2D showed a 24% reduced risk of the composite primary outcome of stroke and myocardial infarction in the pioglitazone arm compared with placebo over a median follow-up of 4.8 years.30 In this MR analysis, genetically predicted higher fasting insulin was associated with a nonsignificant higher odds of large artery stroke.

The lack of a clear association between genetically predicted fasting glucose and insulin and large artery stroke suggests that other pathways might explain the association with T2D. Observational studies have reported that T2D is associated with increased arterial stiffness,31,32 which is a risk factor for stroke.33 In addition, a causal association between T2D and arterial stiffness was found in a recent MR study.34 Stiffening of the arteries may result in the development of atherosclerotic carotid plaques35 and increased risk of large artery stroke.36

The present study did not detect a statistically significant association between genetically predicted BMI and ischemic stroke or its subtypes. Results from a recent meta-analysis of 6 cohort studies conducted in Europe, the United States, and Australia, with a total of 14,443 ischemic stroke cases, showed a 22% increase in ischemic stroke risk per 5-kg/m2 increase in BMI.5 Because our MR study had limited statistical power to detect such a small increase in risk, we cannot rule out the possibility of a causal association between BMI and ischemic stroke. A previous MR study that included 23,782 participants and 3,813 stroke cases observed no association between a genetic instrument comprising 14 BMI-associated SNPs and risk of all strokes (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.95–1.12 per 1-kg/m2 increase in BMI).37 However, another MR study including 20,055 participants and 1,500 ischemic stroke cases found a statistically significant association of genetically predicted higher BMI, assessed with a genetic instrument comprising 32 BMI-associated SNPs, with increased risk of ischemic stroke (hazard ratio 1.83, 95% CI 1.05–3.20 per 4.5-kg/m2 increase in BMI).38

Chief strengths of this study include the large number of total ischemic stroke cases and data on etiologic subtypes of ischemic stroke. Moreover, as a result of the MR design, reverse causation bias was prevented and potential confounding was reduced because genetic variants are not associated with self-selected dietary and lifestyle factors that may affect results from observational studies.

The MR approach also has limitations. First, pleiotropy (i.e., the genetic association with the outcome is through a different causal pathway and not via the risk factor of interest) could have influenced our results. However, our main finding for T2D and large artery stroke was consistent in sensitivity analyses using the weighted median and MR-Egger methods and remained after the exclusion of pleiotropic SNPs associated with lipids. MR-Egger regression provides a valid test of directional pleiotropy and a valid test of the causal null hypothesis under the instrument strength independent of direct effect assumption that the direct pleiotropic effects of the genetic variants on the outcome are distributed independently of the genetic association with the exposure.20 Second, we could not assess whether canalization (i.e., compensatory mechanisms)7 may have affected our results. Canalization tends to attenuate the estimates and thus cannot explain the association between T2D and large artery stroke but might have contributed to the lack of association of the other risk factors with ischemic stroke. Third, we cannot entirely rule out population stratification as a source of bias in this study. Nevertheless, restriction of the data to largely European-descent individuals reduced potential bias due to population stratification. Fourth, the MR assumptions are somewhat stricter for binary exposures such as T2D than for continuous exposures. For MR analysis of binary exposures, the monotonicity assumption must hold.39 Within the context of MR, the monotonicity assumption implies that any effect of the genetic instrument on the exposure is in the same direction for all persons. We cannot rule out the possibility that our results for T2D may have been biased as a result of monotonicity violations.

A further limitation is that the genetic variants associated with the risk factors under study explain only a small fraction of the variation in the risk factors. For example, the BMI-associated SNPs account for <3% of the variation in BMI.18 This low variability, together with the relatively small sample sizes for the analyses of ischemic stroke subtypes, resulted in low precision. Thus, we cannot exclude that the lack of significant associations of fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and BMI with ischemic stroke subtypes is due to insufficient statistical power. Another limitation is that the genetic effects on fasting glucose and insulin were estimated in individuals without diabetes mellitus, whereas our analyses included both diabetics and nondiabetics. Finally, we could not examine potential nonlinear relationships for the continuous risk factors.

This MR study indicates that T2D may be a causal risk factor for large artery stroke but did not confirm the results of observational studies suggesting that higher fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and BMI are associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Further MR studies with larger sample sizes are required to determine whether glucose, insulin, and BMI are causally associated with any ischemic stroke subtype.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- MR

mendelian randomization

- NINDS

National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke

- 1KG

1000 Genomes

- OR

odds ratio

- SiGN

Stroke Genetics Network

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- TOAST

Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment

- T2D

type 2 diabetes mellitus

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Susanna C. Larsson designed the study, performed the statistical analyses, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and drew the figure. Susanna C. Larsson is the corresponding author, takes responsibility for the accuracy of the analysis, and had authority over manuscript preparation and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Robert A. Scott designed the study, performed the statistical analyses, and reviewed and commented on the manuscript. Matthew Traylor, Claudia C. Langenberg, George Hindy, Olle Melander, Marju Orho-Melander, Sudha Seshadri, and Nicholas J. Wareham reviewed and commented on the manuscript. Hugh S. Markus designed the study and reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

METASTROKE 1000K Discovery Constituent Studies. Australian Stroke Genetics Collaboration (ASGC) Australian population control data were derived from the Hunter Community Study. This research was funded by grants from the Australian National and Medical Health Research Council (project grant 569257), Australian National Heart Foundation (project grant G 04S 1623), University of Newcastle, Gladys M. Brawn Fellowship scheme, and Vincent Fairfax Family Foundation in Australia. Genes Affecting Stroke Risk and Outcome Study (GASROS) was supported by NINDS (U01 NS069208), the American Heart Association/Bugher Foundation Centers for Stroke Prevention Research 0775010N, the NIH and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s STAMPEED genomics research program (R01 HL087676), and a grant from the National Center for Research Resources. The Broad Institute Center for Genotyping and Analysis is supported by grant U54 RR020278 from the National Center for Research Resources. Genetics of Early Onset Stroke (GEOS) Study, Baltimore, MD, was supported by the NIH Genes, Environment and Health Initiative (GEI) grant U01 HG004436 as part of the GENEVA consortium under GEI, with additional support provided by the Mid-Atlantic Nutrition and Obesity Research Center (P30 DK072488), the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, and the Baltimore Geriatrics Research, Education, and Clinical Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Genotyping services were provided by the Johns Hopkins University Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR), which is fully funded through a federal contract from the NIH to Johns Hopkins University (contract HHSN268200782096C). Assistance with data cleaning was provided by the GENEVA Coordinating Center (U01 HG 004446; principal investigator Bruce S. Weir). Study recruitment and assembly of datasets were supported by a cooperative agreement with the Division of Adult and Community Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and by grants from NINDS and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (R01 NS45012, U01 NS069208-01). Heart Protection Study (HPS) (ISRCTN48489393) was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC), British Heart Foundation, Merck and Co (manufacturers of simvastatin), and Roche Vitamins Ltd (manufacturers of vitamins). Genotyping was supported by a grant to Oxford University and CNG from Merck and Co. Ischemic Stroke Genetics Study (ISGS)/Siblings With Ischemic Stroke Study (SWISS) was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH project Z01 AG-000954-06. ISGS/SWISS used samples and clinical data from the NIH-NINDS Human Genetics Resource Center DNA and Cell Line Repository (http://ccr.coriell.org/ninds), human participant protocols 2003-081 and 2004-147. ISGS/SWISS used stroke-free participants from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) as controls. The inclusion of BLSA samples was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIA, NIH project Z01 AG-000015-50, human participant protocol 2003-078. This study used the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the NIH (http://biowulf.nih.gov). Milano-Besta Stroke Register Collection and genotyping of the Milan cases within Cerebrovascular Diseases Registry (CEDIR) were supported by Annual Research Funding of the Italian Ministry of Health (grants RC 2007/LR6, RC 2008/LR6, RC 2009/LR8, RC 2010/LR8). FP6 LSHM-CT-2007-037273 for the PROCARDIS control samples. Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2) was principally funded by the Wellcome Trust as part of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 project (085475/B/08/Z and 085475/Z/08/Z and WT084724MA). The Stroke Association provided additional support for collection of some of the St George's, London cases. The Oxford cases were collected as part of the Oxford Vascular Study which is funded by the MRC, Stroke Association, Dunhill Medical Trust, National Institute of Health Research (NIHR), and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford. The Edinburgh Stroke Study was supported by the Wellcome Trust (clinician scientist award to C. Sudlow) and the Binks Trust. Sample processing occurred in the Genetics Core Laboratory of the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh. Much of the neuroimaging occurred in the Scottish Funding Council Brain Imaging Research Centre (www.sbirc.ed.ac.uk), Division of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Edinburgh, a core area of the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility and part of the Scottish Imaging Network—A Platform for Scientific Excellence (SINAPSE) collaboration (www.sinapse.ac.uk), funded by the Scottish Funding Council and the Chief Scientist Office. Collection of the Munich cases and data analysis was supported by the Vascular Dementia Research Foundation. Vitamin Intervention Stroke Prevention (VISP) The GWAS component of the VISP study was supported by the US National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), grant U01 HG005160 (principal investigators Michèle Sale and Bradford Worrall), as part of the Genomics and Randomized Trials Network (GARNET). Genotyping services were provided by the Johns Hopkins University CIDR, which is fully funded through a federal contract from the NIH to Johns Hopkins University. Assistance with data cleaning was provided by the GARNET Coordinating Center (U01 HG005157; principal investigator Bruce S. Weir). Study recruitment and collection of datasets for the VISP clinical trial were supported by an investigator-initiated research grant (R01 NS34447; principal investigator James Toole) from the US Public Health Service, NINDS, Bethesda, MD. Control data for comparison with VISP stroke cases were from the dbGaP Study High Density SNP Association Analysis of Melanoma: Case-Control and Outcomes Investigation (phs000187.v1.p1; R01CA100264, 3P50CA093459, 5P50CA097007, 5R01ES011740, 5R01CA133996, HHSN268200782096C; principal investigators Christopher Amos, Qingyi Wei, Jeffrey E. Lee). Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Funding support for WHI-GARNET was provided through the NHGRI GARNET (grant U01 HG005152). Assistance with phenotype harmonization and genotype cleaning, as well as with general study coordination, was provided by the GARNET Coordinating Center (U01 HG005157). Funding support for genotyping, which was performed at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, was provided by the NIH GEI (U01 HG004424). Hugh S. Markus is supported by an NIHR Senior Investigator award, and his work is supported by the Cambridge Universities NIHR Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Endres M, Heuschmann PU, Laufs U, Hakim AM. Primary prevention of stroke: blood pressure, lipids, and heart failure. Eur Heart J 2011;32:545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markus HS, Bevan S. Mechanisms and treatment of ischaemic stroke: insights from genetic associations. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Traylor M, Farrall M, Holliday EG, et al. Genetic risk factors for ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (the METASTROKE collaboration): a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:951–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah AD, Langenberg C, Rapsomaniki E, et al. Type 2 diabetes and incidence of cardiovascular diseases: a cohort study in 1.9 million people. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroll ME, Green J, Beral V, et al. Adiposity and ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: prospective study in women and meta-analysis. Neurology 2016;87:1473–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gast KB, Tjeerdema N, Stijnen T, Smit JW, Dekkers OM. Insulin resistance and risk of incident cardiovascular events in adults without diabetes: meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7:e52036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. “Mendelian randomization”: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malik R, Traylor M, Pulit SL, et al. Low-frequency and common genetic variation in ischemic stroke: the METASTROKE collaboration. Neurology 2016;86:1217–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meschia JF, Arnett DK, Ay H, et al. Stroke Genetics Network (SiGN) study: design and rationale for a genome-wide association study of ischemic stroke subtypes. Stroke 2013;44:2694–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke: definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial: TOAST: Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NINDS Stroke Genetics Network (SiGN), International Stroke Genetics Consortium (ISGC). Loci associated with ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (SiGN): a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:174–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genome of the Netherlands Consortium. Whole-genome sequence variation, population structure and demographic history of the Dutch population. Nat Genet 2014;46:818–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong A, Steinthorsdottir V, Masson G, et al. Parental origin of sequence variants associated with complex diseases. Nature 2009;462:868–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet 2010;42:579–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet 2010;42:105–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, et al. Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2012;44:981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott RA, Lagou V, Welch RP, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nat Genet 2012;44:991–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015;518:197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol 2013;37:658–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:512–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol 2016;40:304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 2010;466:707–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet 2013;45:1274–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Genome-wide meta-analyses identify multiple loci associated with smoking behavior. Nat Genet 2010;42:441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rolfe Ede L, Loos RJ, Druet C, et al. Association between birth weight and visceral fat in adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forouhi NG, Luan J, Hennings S, Wareham NJ. Incidence of type 2 diabetes in England and its association with baseline impaired fasting glucose: the Ely study 1990–2000. Diabet Med 2007;24:200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as a risk factor for stroke in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts, including 775,385 individuals and 12,539 strokes. Lancet 2014;383:1973–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ADVANCE-Collaborative-Group, Patel A, MacMahon S, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group, Gerstein HC, Miller ME, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2545–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Furie KL, et al. Pioglitazone after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1321–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henry RM, Kostense PJ, Spijkerman AM, et al. Arterial stiffness increases with deteriorating glucose tolerance status: the Hoorn Study. Circulation 2003;107:2089–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salomaa V, Riley W, Kark JD, Nardo C, Folsom AR. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and fasting glucose and insulin concentrations are associated with arterial stiffness indexes: the ARIC Study: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation 1995;91:1432–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Sloten TT, Sedaghat S, Laurent S, et al. Carotid stiffness is associated with incident stroke: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:2116–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu M, Huang Y, Xie L, et al. Diabetes and risk of arterial stiffness: a mendelian randomization analysis. Diabetes 2016;65:1731–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selwaness M, van den Bouwhuijsen Q, Mattace-Raso FU, et al. Arterial stiffness is associated with carotid intraplaque hemorrhage in the general population: the Rotterdam study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34:927–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derdeyn CP. Mechanisms of ischemic stroke secondary to large artery atherosclerotic disease. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2007;17:303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmes MV, Lange LA, Palmer T, et al. Causal effects of body mass index on cardiometabolic traits and events: a mendelian randomization analysis. Am J Hum Genet 2014;94:198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagg S, Fall T, Ploner A, et al. Adiposity as a cause of cardiovascular disease: a mendelian randomization study. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:578–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burgess S, Small DS, Thompson SG. A review of instrumental variable estimators for mendelian randomization. Stat Methods Med Res Epub 2015 Aug 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.