This randomized clinical trial examines whether a pediatric-based behavioral intervention targeting anxiety and depression improves clinical outcome compared with referral to community mental health care.

Key Points

Question

Can a pediatric-based brief behavioral treatment outperform assisted referral to outpatient mental health for youths with anxiety and depression?

Findings

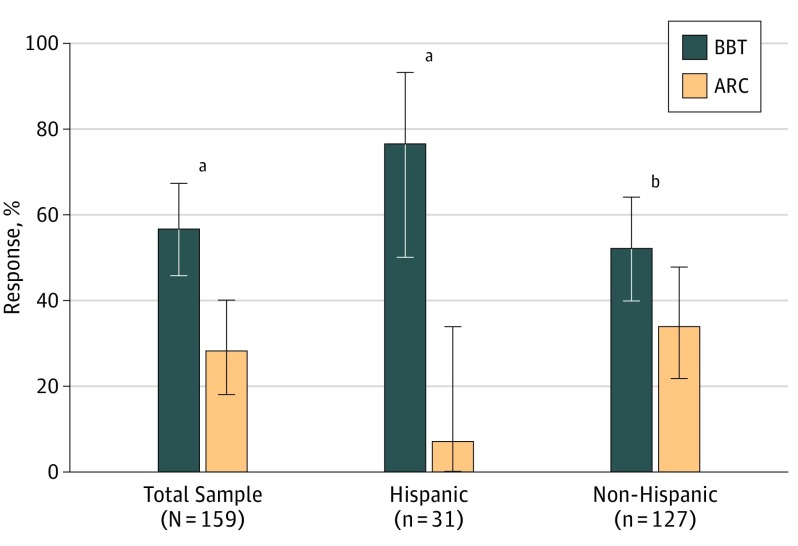

In this randomized clinical trial, 56.8% of youths in pediatric-based behavioral treatment were clinically improved compared with 28.2% of youths provided with assisted referral, a significant difference. Effects were significantly stronger for Hispanic youths, with 76.5% of those in behavioral treatment improving compared with 7.1% of referred youths.

Meaning

A pediatric-based brief behavioral treatment for anxiety and depression can produce benefits superior to those of assisted referral to outpatient mental health care and may address ethnic disparities in outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Anxiety and depression affect 30% of youth but are markedly undertreated compared with other mental disorders, especially in Hispanic populations.

Objective

To examine whether a pediatrics-based behavioral intervention targeting anxiety and depression improves clinical outcome compared with referral to outpatient community mental health care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This 2-center randomized clinical trial with masked outcome assessment conducted between brief behavioral therapy (BBT) and assisted referral to care (ARC) studied 185 youths (aged 8.0-16.9 years) from 9 pediatric clinics in San Diego, California, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, recruited from October 6, 2010, through December 5, 2014. Youths who met DSM-IV criteria for full or probable diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, major depression, dysthymic disorder, and/or minor depression; lived with a consenting legal guardian for at least 6 months; and spoke English were included in the study. Exclusions included receipt of alternate treatment for anxiety or depression, presence of a suicidal plan, bipolar disorder, psychosis, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance dependence, current abuse, intellectual disability, or unstable serious physical illness.

Interventions

The BBT consisted of 8 to 12 weekly 45-minute sessions of behavioral therapy delivered in pediatric clinics by master’s-level clinicians. The ARC families received personalized referrals to mental health care and check-in calls to support accessing care from master’s-level coordinators.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was clinically significant improvement on the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement scale (score ≤2). Secondary outcomes included the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised, and functioning.

Results

A total of 185 patients were enrolled in the study (mean [SD] age, 11.3 [2.6] years; 107 [57.8%] female; 144 [77.8%] white; and 38 [20.7%] Hispanic). Youths in the BBT group (n = 95), compared with those in the ARC group (n = 90), had significantly higher rates of clinical improvement (56.8% vs 28.2%; χ21 = 13.09, P < .001; number needed to treat, 4), greater reductions in symptoms (F2,146 = 5.72; P = .004; Cohen f = 0.28), and better functioning (mean [SD], 68.5 [10.7] vs 61.9 [11.9]; t156 = 3.64; P < .001; Cohen d = 0.58). Ethnicity moderated outcomes, with Hispanic youth having substantially stronger response to BBT (76.5%) than ARC (7.1%) (χ21 = 14.90; P < .001; number needed to treat, 2). Effects were robust across sites.

Conclusions and Relevance

A pediatric-based brief behavioral intervention for anxiety and depression is associated with benefits superior to those of assisted referral to outpatient mental health care. Effects were especially strong for Hispanic participants, suggesting that the protocol may be a useful tool in addressing ethnic disparities in care.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01147614

Introduction

Anxiety and mood disorders in youth are prevalent and impairing, with a high degree of current and lifetime comorbidity in part because of shared etiologic factors. These patients also are markedly undertreated, with only 1 in 5 anxious youths and 2 in 5 depressed youths reporting any lifetime mental health service use for these disorders, the lowest treatment rates for any pediatric mental health disorder. Furthermore, there are notable ethnic disparities in care, with Hispanic youths significantly less likely to receive mental health services than similarly affected non-Hispanic white youths, despite experiencing similar or higher rates of anxiety and depression.

To improve access to and quality of care, the current trial tested the effectiveness of a brief behavioral therapy (BBT) developed to efficiently target anxiety and depression as a unified problem area. There is increasing support for the efficacy of transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral interventions for emotional disorders in adults and preliminary support for such interventions in youths. The BBT trial built on this work by testing a streamlined behavioral intervention without the cognitive restructuring elements present in other programs to aid in the dissemination of BBT to active service settings. The intervention was sited in pediatric primary care, a major focus of public health efforts to improve access to mental health services and a setting with low cultural stigma.

Thus, in the current trial, youths with full or probable diagnoses of anxiety, depression, or both were randomly assigned to (1) transdiagnostic BBT delivered in pediatric primary care or (2) assisted referral to outpatient mental health care (ARC). The ARC was designed to maximize youth participation in specialty mental health care services and serve as a public health comparison condition. We hypothesized that, compared with ARC, BBT would have higher rates of clinical response (primary outcome), greater reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms, and higher global functioning after intervention. We planned a priori to test for moderation of BBT effects by site, Hispanic ethnicity, and presence of clinically significant depression in youths, given epidemiologic data suggesting that anxiety would be widely prevalent in the sample, with comorbid depression occurring at a lower rate.

Methods

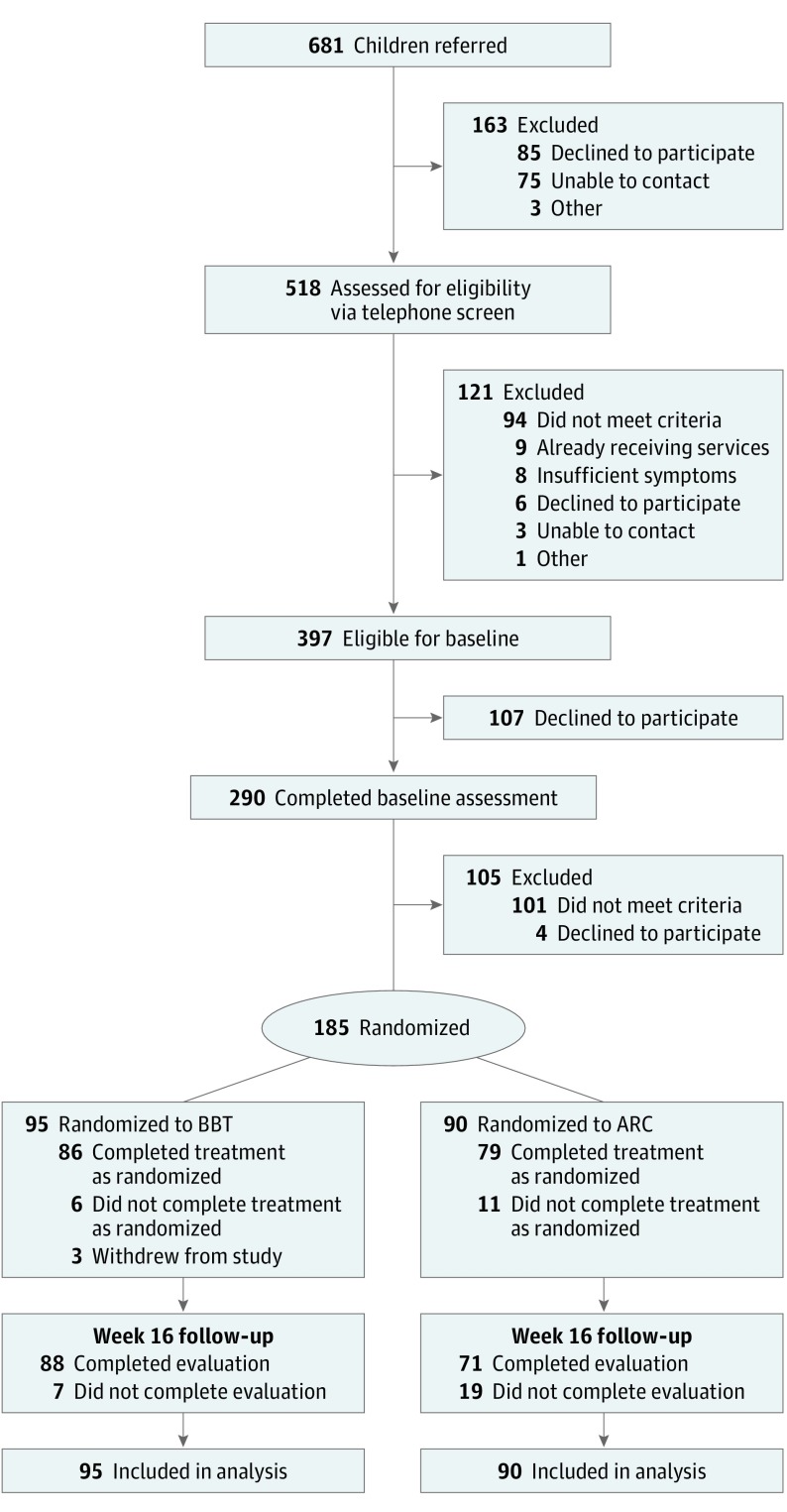

Youths (age range, 8.0-16.9 years) were recruited from 9 pediatric clinics in San Diego, California (n = 4), and the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, metropolitan area (n = 5) from October 6, 2010, through December 5, 2014. Participant flow is shown in Figure 1. The trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1. Participants were clinically referred by pediatrics staff (n = 620) or self-referred from flyers in practices (n = 62). Youths were eligible for randomization if they met the criteria at baseline for full or probable (Clinical Global Impression–Severity score [CGI-S] >3) diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, major depression, dysthymic disorder, or minor depression; lived with a consenting legal guardian for at least 6 months; and both the youth and 1 participating caretaker spoke English. Exclusions included receipt of concurrent active treatment for anxiety or depression, current suicidal plan, bipolar disorder, psychosis, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance dependence, current abuse, report of intellectual disability or school placement below second grade, or report of unstable serious physical illness. Participants were randomized using Begg and Iglewicz's modification of Efron's biased coin toss to balance on sex, race/ethnicity, and the presence of clinically elevated depression (probable depression diagnosis and/or elevated Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised [CDRS-R]). The San Diego State University Human Research Protection Program, Kaiser Permanente Southern California Institutional Review Board, and University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved study procedures; safety was reviewed by a data safety monitoring board. Written informed consent and assent were obtained from participating parents and youths before initiation of study procedures. Analyses were conducted in a deidentified data file.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram Detailing Study Flow of Participants From Screening to Analysis.

ARC indicates assisted referral to care; BBT, brief behavioral therapy.

BBT Intervention

The BBT transdiagnostic intervention was developed to address youth anxiety, depression, and their comorbid presentation by integrating the core behavioral elements of evidence-based treatments for these individual disorders. Rationale for treatment development and detailed session content are available elsewhere. In brief, exposure and behavioral activation were combined in the current protocol as graded engagement in avoided activities, supplemented by relaxation to manage somatic symptoms common among internalizing youth in primary care and by problem-solving skills to aid in stress management. Note that all these techniques had been tested previously in clinical trials as components of other treatment protocols. The BBT manual was novel in its simplicity (fewer total techniques than most manuals), the exclusion of cognitive restructuring in favor of behavioral techniques, and the integration of psychoeducation and treatment techniques to efficiently address anxious and depressed symptoms simultaneously. The BBT consisted of 8 to 12 weekly 45-minute sessions completed within 16 weeks. All sessions were delivered in the primary care setting by master’s-level study therapists (4 including M.S.R.). Therapist training consisted of a half-day workshop with the manual developer, review of recordings of 2 training cases, and completion of a session-by-session role play. Audio recordings of the first 4 cases for each therapist were reviewed in detail with the clinical trial supervisor (V.R.W.); after this training phase, therapists received 1 hour of weekly supervision to review their caseload.

ARC Procedures

The ARC procedures were modeled on evidence-based practices for reducing no-show rates in community mental health care. The ARC included (1) feedback about the youth’s symptoms and benefit of services, (2) referrals and education about obtaining services, and (3) problem-solving barriers to treatment. The master’s-level coordinator (5 during the study period, including M.S.R. and M.J.) contacted the youth’s primary caregiver, implemented an initial ARC session by telephone, and continued to call the parent at least every 2 weeks to check in and problem solve obstacles to care with families through the end of the acute treatment phase.

Assessments

Assessments were performed by clinical independent evaluators (IEs), masked to condition. Baselines occurred onsite in practices; follow-up assessments were conducted over the telephone. The IEs were required to demonstrate 80% agreement on at least 5 training tapes before conducting study assessments and engaged in weekly supervision.

Measures

Demographic data were collected by parent and youth report. Parents reported on youth race/ethnicity from US Census categories. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version was used to assess baseline diagnostic eligibility. The Clinical Global Impressions scale was used to assess global severity (CGI-S) and improvement (CGI-I) across anxiety and depression. A CGI-I score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) at the week 16 assessment indicated clinical response. The IEs rated functional impairment with the Children's Global Adjustment Scale (CGAS), anxiety severity with the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS), and depression with the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R). Interrater reliability was good across all outcome measures (intraclass correlation coefficients = 0.70-0.95). The Child and Adolescent Services Assessment was administered to measure health service use for both conditions and describe ARC services obtained.

Statistical Analysis and Data Analytic Plan

The primary registered outcome of the trial was clinically significant improvement of anxiety and depression (CGI-I score ≤2). Secondary outcomes included the PARS, CDRS-R, and functioning scores; we further analyzed treatment dose and mental health service use. Logistic regression methods and χ2 tests were used for categorical measures and t tests for continuous measures. Given the association between change in anxiety and depression in the literature, we adopted a doubly multivariate repeated-measures approach to jointly analyze changes in the PARS and CDRS-R scores. Moderator analysis followed the standard Barron and Kenny and Kraemer frameworks. With a functional sample size of 79, we were powered to detect an effect size in the order of 0.60 for the difference in improvement rate between BBT and ARC. To calculate power for our moderator analyses of the CGI-I, we conducted simulations based on work by MacKinnon and colleagues. Including 3 moderators (ethnicity, clinically significant depression, and site), power was adequate (>0.80) to detect medium (0.46) effects. All significance tests were 2-tailed, and analyses were designed as intention to treat; α was set at P < .05 for all tests.

To estimate the effect of missing data, we conducted sensitivity analyses for each outcome by (1) performing the planned analyses in the unadjusted intention-to-treat sample, (2) repeating these models in an imputed data set in which missing data were estimated by multiple imputation with chained equations, and (3) including as covariates participant characteristics significantly associated with attrition. Across these methods, interpretation of results remained unchanged; thus, for simplicity, we present the unadjusted intention-to-treat analyses herein.

Results

Sample Characteristics and Retention

A total of 185 patients were enrolled in the study (mean [SD] age, 11.3 [2.6] years; 107 [57.8%] female; 144 [77.8%] white; and 38 [20.7%] Hispanic). At baseline, the enrolled sample did not significantly differ by group on demographic or clinical characteristics (Table 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 2). As expected, the sample was broadly anxious, with 114 youths (61.6%) meeting the criteria for 1 or more anxiety disorders, 60 (32.4%) having anxiety and clinically elevated depression, and 11 (5.9%) having clinically significant depression without current anxiety.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics Overall and by Groupa.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 185) |

ARC (n = 90) |

BBT (n = 95) |

Test | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 11.3 (2.6) | 11.3 (2.7) | 11.3 (2.4) | t183 = 0.10 | .92 | |

| Females | 107 (57.8) | 53 (58.9) | 54 (56.8) | χ21 = 0.08 | .78 | |

| White | 144 (77.8) | 73 (81.1) | 71 (74.7) | χ21 = 1.09 | .30 | |

| Hispanic | 38 (20.7) | 20 (22.5) | 18 (18.9) | χ21 = 0.35 | .56 | |

| Living with both biological parents | 125 (67.6) | 58 (64.4) | 67 (70.5) | χ21 = 0.78 | .38 | |

| Parent at least a college graduate | 116 (63.7) | 55 (61.8) | 61 (65.6) | χ21 = 0.28 | .60 | |

| Treated in San Diego, California | 96 (51.9) | 47 (52.2) | 49 (51.6) | χ21 = 0.01 | .93 | |

| Family monthly income (in thousands), median (range), $ | 4.4 (0-21) | 4.4 (0-18) | 4.2 (0.6-21) | z = −0.33 | .74 | |

| Clinically significant depression | 71 (38.4) | 35 (38.9) | 36 (37.9) | χ21 = 0.02 | .89 | |

| CDRS-R score, mean (SD) | 32.9 (12.6) | 33.7 (12.5) | 32.2 (12.6) | t182 = 0.84 | .40 | |

| CGI-S score, mean (SD) | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.1 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.8) | t183 = −0.95 | .34 | |

| CGAS score, mean (SD) | 56.1 (6.5) | 56.4 (7.1) | 55.9 (6.5) | t183 = 0.56 | .58 | |

| PARS score, mean (SD) | 14.9 (5.2) | 14.4 (5.1) | 15.3 (5.3) | t183 = −1.10 | .27 |

Abbreviations: ARC, assisted referral to care; BBT, brief behavioral therapy; CDRS-R, Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised; CGAS, Children's Global Adjustment Scale; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression–Severity; PARS, Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale.

Data are presented as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Of the 185 randomized youths, 159 (85.9%) completed the week 16 assessment (Figure 1). Participants unavailable for follow-up had significantly higher depression and lower functioning scores (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Retention did not differ by site (Pittsburgh vs San Diego: 88.9% vs 83.3%; χ21 = 1.13; P = .29), although there was a higher retention rate in the BBT group than in the ARC group (92.6% vs 78.9%; χ21 = 7.23; P = .01).

Clinical Outcomes

Outcomes Across Anxiety and Depression

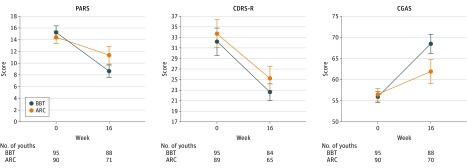

As seen in Figure 2, 50 (56.8%) of the 88 BBT youth were rated as responders on our primary outcome measure (CGI-I score ≤2) at week 16 compared with only 20 (28.2%) of 71 youths in the ARC group (χ21 = 13.09; P < .001; number needed to treat [NNT], 4; 95% CI, 2.3-7.2). The rate of functional improvement in the BBT youths also was significantly faster (β = 0.44; SE, 0.10; z = 4.45; P < .001; Cohen d = 0.50) and the level of functioning higher at week 16 (mean [SD], 68.5 [10.7] vs 61.9 [11.9]; t156 = 3.64; P < .001; Cohen d = 0.58; 95% CI, 0.26-0.90) than in ARC youths (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Response (Clinical Global Impression–Improvement Score ≤2) at Week 16 to Brief Behavioral Therapy (BBT) and Assisted Referral to Care (ARC) for Total Sample and by Hispanic Ethnicity.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

aP < .001 for comparison of BBT and ARC.

bP = .04 for comparison of BBT and ARC.

Figure 3. Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS), Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R), and Children's Global Adjustment Scale (CGAS) Scores by Arm From Baseline to Week 16.

ARC indicates assisted referral to care; BBT, brief behavioral therapy. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Outcome by Psychopathological Domain

As seen in Figure 3 and Table 2, there was a significant effect of time, with anxiety and depression scores improving from baseline to week 16 (F2,146 = 54.03; P < .001; Cohen f = 0.86). In addition, there was a significant treatment × time interaction, such that youths in the BBT group had a faster rate of improvement than youths randomized to the ARC group (F2,146 = 5.72; P = .004; Cohen f = 0.28). These effects appear to be largely driven by the superior effect of BBT on anxiety (F1,147 = 11.47; P = .01; Cohen f = 0.28); the treatment × time interaction for the CDRS-R was not statistically significant (F1,147 = 0.78; P = .38; Cohen f = 0.07).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Outcome Measures at Baseline and Week 16 by Group.

| Outcome Measure | Baseline | Week 16 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARC | BBT | ARC | BBT | |||||

| Mean (SD) | No. | Mean (SD) | No. | Mean (SD) | No. | Mean (SD) | No. | |

| PARS score | 14.4 (5.1) | 90 | 15.3 (5.3) | 95 | 11.4 (6.4) | 71 | 8.6 (5.0) | 88 |

| CDRS-R score | 33.7 (12.5) | 89 | 32.2 (12.6) | 95 | 25.2 (9.4) | 65 | 22.6 (7.3) | 84 |

| CGAS score | 54.4 (7.1) | 90 | 55.9 (6.5) | 95 | 61.9 (11.9) | 70 | 68.5 (10.7) | 88 |

| CGI-S score | 4.1 (0.8) | 90 | 4.2 (0.8) | 95 | 3.4 (1.3) | 71 | 2.6 (1.2) | 88 |

| CGI-I score | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.1 (1.3) | 71 | 2.3 (1.1) | 88 |

Abbreviations: ARC, assisted referral to care; BBT, brief behavioral therapy; CDRS-R, Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised; CGAS, Children's Global Adjustment Scale; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression–Improvement; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression–Severity; NA, not applicable; PARS, Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale.

Moderation

Ethnicity significantly moderated response (odds ratio, 19.94; SE, 24.74; z = 2.41; P = .02), with Hispanic youths having heightened response to BBT and little response to ARC (13 [76.5%] of 17 vs 1 [7.1%] of 14; χ21 = 14.90; P < .001; NNT, 2; 95% CI, 1.1-2.2) (Figure 2). Ethnicity also significantly moderated changes in functioning (β = 10.13; SE, 4.12; t = 2.46; P = .02; Cohen d = 0.49). Hispanic youths in the BBT group improved by a mean of 15.5 points on the CGAS, shifting 2 qualitative functioning categories; in contrast, the mean CGAS score change for Hispanic youths in the ARC group was less than 1 point. Even when removing these strong effects for Hispanic youths, in the non-Hispanic white subgroup, the main effects of treatment on response (BBT vs ARC: 37 [52.1%] of 71 vs 19 [33.9%] of 56; χ21 = 4.20; P = .04; NNT, 6; 95% CI, 2.8-84.0) and functioning (β = 5.05; SE, 1.89; t = 2.67; P = .01; Cohen d = 0.49) remained statistically significant and clinically meaningful. Clinically significant depression in youths at baseline did not moderate the BBT response on any outcome: depression as moderator of response (odds ratio, 0.44; SE, 0.31; z = −1.17, P = .24), depression as moderator of CGAS (functioning) (β = −4.73; SE, 3.44; t = −1.37; P = .17; Cohen d = 0.23), and depression as moderator of anxiety and depression scores (F2,144 = 0.90; P = .41; Cohen f = 0.11). Study site moderated BBT effects on functioning (β = 7.61; SE, 3.27; t = 2.33; P = .02; Cohen d = 0.37), with larger effects in San Diego. This site effect appeared to be accounted for by the higher proportion of Hispanic youth in the San Diego sample. When Hispanic youths were excluded from analysis, site effects on functioning were no longer statistically significant (β = 4.67; SE, 3.92; t = 1.19; P = .24; Cohen d = 0.22). In addition, the main effect of treatment on functioning was robust across both sites (F1,154 = 18.64; P < .001; Cohen f = 0.35), and site did not moderate any other outcomes.

Allocation Concealment

As a check on allocation concealment, IEs (masked to treatment condition) were asked to guess participant group assignment after interview completion at week 16. The IEs correctly guessed participants’ allocation at a rate higher than chance (64.8%; χ21 = 13.89; P < .001). However, correct guess by the IEs was not significantly associated with ratings of improvement (58.4% vs 72.9%; χ21 = 3.58; P = .06).

Treatment Implementation and Service Use

The BBT was administered with high adherence, with a mean of 96% of manual content delivered (rated from a randomly selected 10% of sessions). The BBT youth attended a mean of 11.2 sessions, and 85 youths (90.4%) received at least a minimum protocol dose of at least 8 sessions.

The ARC condition was successfully delivered, with a mean of 4.2 coordinator calls provided during the 16 weeks to promote engagement in services and assess youths' clinical status and needs. The ARC coordinators connected 82.2% of families with specialty mental health care for a mean of 6.5 outpatient sessions (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). We probed whether youths in the ARC group who received more services had outcomes comparable to youth in the BBT group. We divided the ARC youth into high-dose (≥7 outpatient visits; n = 34) and low-dose (<7 visits; n = 47) groups. In the ARC group, high- and low-dose youths did not significantly differ on any outcome metric: (response: P = .11; functioning: P = .22; anxiety and depression scores: P = .74). We further compared high-dose ARC youths with youths enrolled in BBT. Across analyses, participants in the ARC high-dose group had significantly worse outcomes than youths randomized to BBT: response (BBT vs ARC: 50 [56.8%] of 88 vs 6 [18.8%] of 32; χ21 = 13.66; P < .001; NNT, 3; 95% CI, 1.8-4.8), functioning (β = 8.59; SE, 2.06; t = 4.16; P < .001; Cohen d = 0.92), and anxiety and depression scores (F2,109 = 4.26; P = .02; Cohen d = 0.56). Of note, Hispanic ethnicity was not significantly related to receipt (Hispanic vs non-Hispanic: 15 [88.2%] of 17 vs 58 [92.1%] of 63; Fisher exact test, P = .64) or dose (mean [SD] visits, Hispanic vs non-Hispanic: 4.4 [5.6] vs 7.0 [5.7]; z = 1.88; P = .06) of outpatient care in the ARC arm.

Discussion

Anxiety and depression in youth are widely prevalent, highly impairing, and woefully undertreated. In the current trial, youths who were randomized to pediatric-based BBT readily accepted the behavioral treatment (92.6% retained), demonstrated excellent session attendance (mean of 11.2 sessions), and achieved high clinical response rates (56.8%) and substantial functional improvement. The enhanced referral procedures of the ARC comparison condition also were successful in engaging families in community mental health care, with use rates (82%) and session attendance (mean of 6.5 sessions) notably higher than those reported in the health services literature. However, the success of ARC in linking youths to services did not produce clinical outcomes comparable to BBT. The ARC response rate was half that of the BBT, with a corresponding smaller improvement in functioning. These effects were especially stark for Hispanic youths, who had heightened response to BBT (76.5% response rate) and worse outcomes in ARC (7.1%) than did non-Hispanic white youths. Even for non-Hispanic white youths, the response rate for outpatient care in the ARC resembled that of clinical trial control conditions (eg, 24%; Child-Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study), adding to a troubling body of evidence suggesting that typical, eclectic community outpatient services for youths may be of modest effectiveness and reliably less efficacious than evidence-based psychosocial treatment protocols.

Of note, these positive BBT effects occurred for a streamlined, transdiagnostic behavioral intervention that did not include cognitive restructuring elements common to disorder-specific anxiety and depression protocols and to most transdiagnostic protocols. These results join an increasing body of work that suggests that behavioral techniques may be essential active ingredients of more complex psychosocial intervention packages and that it may be possible to simplify interventions for some psychiatric conditions to aid in the dissemination of evidence-based treatment without a decrease in efficacy. Indeed, the absolute response rate for BBT in this pediatric effectiveness trial (56.8%) compares favorably with results of major efficacy trials of cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety (59.7%, Child-Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study) and depression (43.2%, Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study), providing empirical support for policies aimed at improving youth mental health care through expanding pediatric behavioral health care.

The superior effects of BBT were robust to site and presence of clinically elevated depression in youths. Of note, although youths with and without clinically significant depression received similar benefit from BBT, the intervention did not have statistically significant effects on depression symptoms as measured with the CDRS-R. This may be, in part, attributable to floor effects on the outcome measure; only 38% of youths had increased depression at baseline. Youth depression also was associated with study dropout across groups, although sensitivity analyses did not suggest that attrition skewed results. Alternately, BBT may have been less effective in treating depression per se despite the positive effects for depressed youths in terms of overall clinical improvement, functioning, and anxiety severity.

In addition, by design, the effects of the BBT arm included the effect of the specific BBT treatment protocol and the effect of colocation of BBT services in primary care. Colocation of behavioral health is not yet the norm nationally but is becoming increasingly common, with a recent geocoding analysis of Medicaid data suggesting that 43% of primary care physicians may be colocated with a mental health counselor. Integration of primary care and behavioral health is rarer than simple colocation. The positive effects of BBT thus reflect the value of successfully bringing these structured behavioral services to primary care compared with the common option of external referral to community mental health. Planned future analyses will probe cost-effectiveness of the colocated BBT arm compared with ARC referral to community outpatient care. Future research would benefit from additional consideration of workforce development and staff training, practice and health care system characteristics, and provision of care in isolated or rural environments where community mental health resources may be especially minimal.

Limitations

Although the effects of BBT appear to be promising, this trial represents the first test of the transdiagnostic treatment program. It will be important to replicate these outcomes in larger samples, particularly the strong moderation effects for the subsample (n = 38) of Hispanic youth. A larger sample also may have provided the opportunity to test BBT effects on depression more completely. The intervention was designed as a transdiagnostic protocol for anxiety and depression, and although BBT did positively impact overall response, anxiety, and functioning in both anxious and anxious-depressed youths, significant effects were not found for clinician-rated depression symptoms. The proportion of youths with clinically significant depression in the sample may have been insufficient to observe these effects. In addition, the trial provided only a limited test of the effectiveness of the BBT intervention in practice. It is unknown whether BBT would produce positive outcomes if it had been delivered in a dissemination trial using nonresearch staff. Long-term effects of BBT relative to ARC also remain an open question and may be a caveat to the conclusions of the study if ARC youths obtain additional, more effective community services (such as the prescribing of serotonin reuptake inhibitors) at a delay, compared with the quicker initiation of BBT procedures.

Conclusions

A pediatric-based brief behavioral intervention for anxiety and depression is associated with benefits superior to those of assisted referral to outpatient mental health care. Effects were especially strong for Hispanic youth, suggesting that the protocol may be a useful tool in addressing ethnic disparities in care.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics by Site

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics by Completion of Week 16 Assessment

eTable 3. Service Use by Group at Baseline and Cumulative Use From Baseline Through Week 16

References

- 1.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. . Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980-989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bittner A, Egger HL, Erkanli A, Jane Costello E, Foley DL, Angold A. What do childhood anxiety disorders predict? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(12):1174-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A. 10-year Research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(10):972-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(3):225-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, et al. . Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(9):915-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102(1):133-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(1):56-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garber J, Weersing VR. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in youth: implications for treatment and prevention. Clin Psychol (New York). 2010;17(4):293-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. . Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson ER, Mayes LC. Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(3):338-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(4):1-131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glover SH, Pumariega AJ, Holzer CE, Wise BK, Rodriguez M. Anxiety symptomatology in Mexican American adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 1999;8(1):47-57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts RE, Sobhan M. Symptoms of depression in adolescence: a comparison of Anglo, African, and Hispanic Americans. J Youth Adolesc. 1992;21(6):639-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Prevalence of youth-reported DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among African, European, and Mexican American adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1329-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC, Overpeck MD, Sun W, Giedd JN. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(8):760-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Twomey C, O’Reilly G, Byrne M. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2015;32(1):3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu BC, Crocco ST, Esseling P, Areizaga MJ, Lindner AM, Skriner LC. Transdiagnostic group behavioral activation and exposure therapy for youth anxiety and depression: Initial randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2016;76:65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehrenreich JT, Goldstein CM, Wright LR, Barlow DH. Development of a unified protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders in youth. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2009;31(1):20-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 USC §18001-18003 (2010).

- 20.Parity in Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Benefits, 42 USC §300gg-26 (2008).

- 21.Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. . The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41(4):479-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino IT, Hay J, et al. . Effectiveness of collaborative care in addressing depression treatment preferences among low-income Latinos. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(11):1112-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Givens JL, Houston TK, Van Voorhees BW, Ford DE, Cooper LA. Ethnicity and preferences for depression treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(3):182-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):57-87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axelson DA, Birmaher B. Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14(2):67-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):837-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Begg CB, Iglewicz B. A treatment allocation procedure for sequential clinical trials. Biometrics. 1980;36(1):81-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Efron B. Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika. 1971;58(3):403-417. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weersing VR, Gonzalez A, Campo JV, Lucas AN. Brief Behavioral Therapy for pediatric anxiety and depression: Piloting an integrated treatment approach. Cognit Behav Pract. 2008;15(2):126-139. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKay MM, Stoewe J, McCadam K, Gonzales J. Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their caregivers. Health Soc Work. 1998;23(1):9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Census Bureau Race. http://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html July 8, 2013. Accessed May 19, 2016.

- 32.Guy W. Clinical Global Impression Scale In: Guy W, ed. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976:218-222. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. . A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(11):1228-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS): development and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(9):1061-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Children’s Depression Rating Scale – Revised, Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ascher BH, Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Angold A. The Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA) description and psychometrics. J Emot Behav Disord. 1996;4(1):12-20. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garber J, Brunwasser SM, Zerr AA, Schwartz KTG, Sova K, Weersing VR. Treatment and prevention of depression and anxiety in youth: test of cross-over effects. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(10):939-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):83-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, et al. . Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2753-2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weersing VR, Weisz JR. Community clinic treatment of depressed youth: benchmarking usual care against CBT clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(2):299-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Hawley KM, Jensen-Doss A. Performance of evidence-based youth psychotherapies compared with usual clinical care: a multilevel meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(7):750-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. . Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(4):658-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. ; Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Team . Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(7):807-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller BF, Petterson S, Burke BT, Phillips RL Jr, Green LA. Proximity of providers: colocating behavioral health and primary care and the prospects for an integrated workforce. Am Psychol. 2014;69(4):443-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality The Academy; Integrating behavioral health and primary care. http://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov. Accessed January 31, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics by Site

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics by Completion of Week 16 Assessment

eTable 3. Service Use by Group at Baseline and Cumulative Use From Baseline Through Week 16