Clinical and basic evidence suggest that both large artery and small vessel disease contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, one form of dementia.1 Although the study of the cause of Alzheimer’s disease began with a vascular emphasis, the field shifted to a focus on neuronal changes in response to local amyloid β peptides (Aβ), subsequent Tau pathology, and their ultimate effects on cognitive function.1, 2 In more recent years, a partial realignment has occurred, such that vascular disease is again thought to make important contributions to Alzheimer’s disease pathology (along with other dementias) and their impact on brain function.1, 2

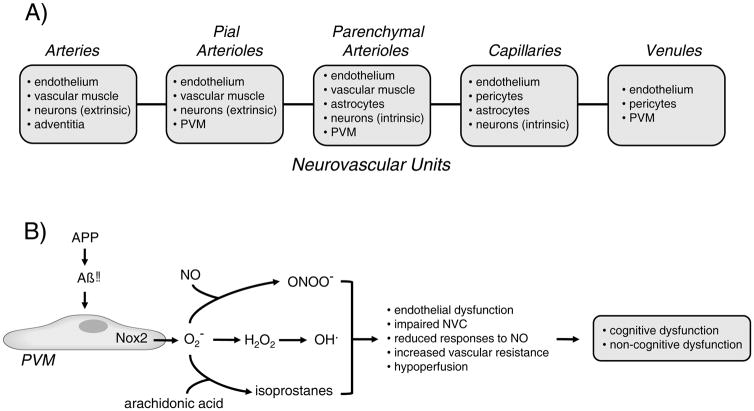

The term neurovascular unit (NVU) is commonly used to emphasis the concept that in brain, vascular cells (endothelium, vascular muscle, pericytes) are closely associated anatomically and functionally with perivascular cells (eg, astrocytes, neurons, and microglia). In the literature, the cellular makeup of the NVU varies. For example, some presentations include vascular muscle, but others do not, despite the fact that vascular muscle is the major effector of rapid changes in lumen diameter in resistance vessels. Reasons for differences in definition are not clear but may include the fact that cellular components of the NVUs vary with progression along the vascular tree (Figure). Within individual segments of the vasculature, further heterogeneity exists. For instance, astrocytic endfeet associate to a fairly high degree with vascular muscle in the striatum but not in the cortex.3 When the discussion relates to the blood-brain barrier (BBB), the focus is typically capillary centric and vascular muscle is often omitted.

Figure.

Schematic illustration of major cell types within the different neurovascular units with progression down the vascular tree (A). In B) Aβ-induced activation of Nox2 containing NADPH oxidase in PVM results in formation of superoxide and potentially several closely related molecules. The potential collective impact of PVM-derived ROS on the vasculature and brain function is also summarized. O2− = superoxide anion; ONOO− = peroxynitrite; H2O2 = hydrogen peroxide; OH. = hydroxyl radical; NVC = neurovascular coupling; NO = nitric oxide. APP = amyloid precursor protein. See text for additional details.

Perivascular macrophages (PVM) are an additional cell within the NVU. This cell type is distinct from peripheral macrophages and the various resident microglia in brain. PVM are found in close proximity to pial arterioles and the more proximal arterioles within the parenchyma, but not more distal arterioles and capillaries (Figure).4, 5 While the presence of PVM within the microcirculation has been known for many years, the functional importance of these cells under normal conditions and in disease is poorly defined.

Previous work implicated oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in effects of Aβ on isolated blood vessels along with regulation of vascular tone and cerebral blood flow (CBF) in vivo.1, 6 Both vascular and non-vascular cells are capable of producing ROS. Thus, multiple cells within or near the vasculature are candidate sources of ROS and sites of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Within vascular cells, a major enzymatic source of ROS are the family of NADPH oxidases.7

In this issue of Circulation Research, Park et al examined the hypothesis that a Nox2 containing NADPH oxidase within PVM is the main source of superoxide that impairs regulation of CBF in models of Aβ-induced pathophysiology.8 To pursue this question, complementary approaches were used that included alterations in local levels of Aβ, pharmacological and genetic manipulation of PVM numbers and genotype, focusing on the role of Nox2 and CD36, a receptor that activates NADPH oxidase in the PVM. The study relied on two models, one that examined acute effects of Aβ1–40, and the second, a genetic model that chronically expresses a Swedish mutation in amyloid precursor protein (APP). Using these models, the impact of Aβ on several key vasodilator mechanisms was quantified. Both acute and chronic exposure to elevated levels of Aβ increased ROS and impaired local CBF responses to endothelium-dependent agonists [both nitric oxide (NO)-dependent and NO-independent], to an NO donor, and to activation of the somatosensory cortex, a model of neurovascular coupling. In contrast, changes in CBF during hypercapnia and local application of adenosine (a vasodilator that acts directly on vascular muscle) were not altered by Aβ.

The authors next addressed potential mechanisms involved. Oxidative stress contributes to vascular abnormalities in many disease models including Alzheimer’s disease.1, 9–11 Depletion of PVM using centrally administered clodronate inhibited increases in ROS and CBF abnormalities in both the acute and chronic models of Aβ-induced dysfunction. In further studies, the use of bone-marrow transfer and genetically altered mice suggested the cell type expressing CD36 and Nox2, and mediating effects of Aβ on regulation of CBF, was the PVM. This conclusion was based on several observations, including the fact that genetic deletion of Nox2 within the PVM prevents effects of Aβ on local levels of ROS and CBF. Findings such as this elevate the PVM from a cellular bystander with unknown intentions to a functionally important contributor to cerebrovascular abnormalities in models of Alzheimer’s disease. The concept that PVM in brain contribute to cerebrovascular disease is also reinforced by recent work in models of hypertension.5

While the study by Park et al8 provides new insight into PVM-dependent mechanisms in brain, new questions emerge and some questions were left unanswered. First, only male mice were used in the study. Because Alzheimer’s disease is more common in women than in men, it will be important to also define the role of central PVM in female preclinical models. Second, the product of Nox2 is superoxide, a precursor to other ROS and related molecules (Figure). Such interactive chemistry raises the question, was the phenotype due to effects of superoxide per se, some downstream molecule, or the collective impact and interaction of several molecules? How does superoxide produced by a PVM affect the distinct cells and regulatory mechanisms that mediate endothelium-dependent vasodilation and neurovascular coupling? Third, while the current study implicates PVM as a key source of superoxide, this cell type is likely not the only producer or superoxide or location of oxidative stress within the vasculature. For example, other work using a similar model of Alzheimer’s disease highlighted endothelial cells as a key site of increased superoxide.12 Thus, although details remain to be defined, it seems likely that multicellular and possibly integrated sites of oxidative stress are involved in changes during Alzheimer’s disease. Fourth, only acute or early vascular effects of Aβ were studied. The potential impact of PVM-mediated changes in regulation of CBF on cognitive or non-cognitive function in brain remains to be determined. Fifth, integrity of the BBB can be lost during Alzheimer’s disease.13 The BBB is present throughout the various segments of the vasculature in brain (Figure).14 Is there a role for PVM in changes in BBB structure and function as well? Lastly, can targeting of PVM in mice after Aβ-dependent disease is established reverse vascular abnormalities and cognitive deficits?

What are the implications of this work? With essentially no energy reserves, adequate resting CBF and effective regulatory mechanisms are needed on a moment to moment basis to ensure precise delivery of oxygen, glucose, and other molecules required for normal brain function. Accumulating evidence suggests that hypoperfusion resulting from abnormalities in this regulation are a prelude and a predictor of dementia.1, 9, 15 The structural and functional changes that produce such reductions in CBF and their underlying mechanisms remain to be fully defined. Manipulation of PVM, a component of the NVU in some segments of the circulation, was sufficient to prevent the impairment of two key adaptive vasodilator mechanisms in models of Alzheimer’s disease. With such work, the shift in concept that disruption in vascular mechanisms plays a major role in the pathophysiology of brain dysfunction and dementias gains further momentum, while highlighting a possible direct role for PVM in small vessel disease.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL-113863, NS-096465, the Department of Veterans Affairs (BX001399), and the Fondation Leducq (Transatlantic Network of Excellence).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

References

- 1.Iadecola C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron. 2013;80:844–866. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Strooper B, Karran E. The cellular phase of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2016;164:603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen ZL, Yao Y, Norris EH, Kruyer A, Jno-Charles O, Akhmerov A, et al. Ablation of astrocytic laminin impairs vascular smooth muscle cell function and leads to hemorrhagic stroke. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:381–395. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201212032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelhardt B, Carare RO, Bechmann I, Flugel A, Laman JD, Weller RO. Vascular, glial, and lymphatic immune gateways of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:317–338. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1606-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faraco G, Sugiyama Y, Lane D, Bonilla LG, Chang H, Santisteban MM, et al. Perivascular macrophages mediate the neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction associated with hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:4674–4689. doi: 10.1172/JCI86950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietrich HH, Xiang C, Han BH, Zipfel GJ, Holtzman DM. Soluble amyloid-beta, effect on cerebral arteriolar regulation and vascular cells. Molecular Neurodegen. 2010;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drummond GR, Sobey CG. Endothelial NADPH oxidases: which NOX to target in vascular disease? Trends Endo Metab. 2014;25:452–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park L, Uekawa K, Garcia-Bonilla L, Koizumi K, Murphy M, Pitstick R, et al. Brain perivascular macrophages initiate the neurovascular dysfunction of Alzheimer Aβ peptides. Circ Res. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311054. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Silva TM, Faraci FM. Microvascular dysfunction and cognitive impairment. Cell Molec Neurobiol. 2016;36:241–258. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0308-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu X, De Silva TM, Chen J, Faraci FM. Cerebral vascular disease and neurovascular injury in ischemic stroke. Circ Res. 2017;120:449–471. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faraci FM. Protecting against vascular disease in brain. Am J Physiol. 2011;300:H1566–1582. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01310.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park L, Zhou P, Pitstick R, Capone C, Anrather J, Norris EH, et al. Nox2-derived radicals contribute to neurovascular and behavioral dysfunction in mice overexpressing the amyloid precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:1347–1352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711568105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kisler K, Nelson AR, Montagne A, Zlokovic BV. Cerebral blood flow regulation and neurovascular dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.48.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanske S, Dyrna F, Bechmann I, Krueger M. Different segments of the cerebral vasculature reveal specific endothelial specifications, while tight junction proteins appear equally distributed. Brain Structure Function. 2017;222:1179–1192. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolters FJ, Zonneveld HI, Hofman A, van der Lugt A, Koudstaal PJ, Vernooij MW, et al. Cerebral perfusion and the risk of dementia: A population-based study. Circulation. 2017 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]