Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reverse transcriptase (RT) associated ribonuclease H (RNase H) remains the only virally encoded enzymatic function not clinically validated as an antiviral target. 2-Hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3-dione (HID) is known to confer active site directed inhibition of divalent metal-dependent enzymatic functions, such as HIV RNase H, integrase (IN) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5B polymerase. We report herein the synthesis and biochemical evaluation of a few C-5, C-6 or C-7 substituted HID subtypes as HIV RNase H inhibitors. Our data indicate that while some of these subtypes inhibited both the RNase H and polymerase (pol) functions of RT, potent and selective RNase H inhibition was achieved with subtypes 8–9 as exemplified with compounds 8c and 9c.

Keywords: 2-hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3-diones; HIV; RNase H; reverse transcriptase; inhibitor

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

HIV encodes three enzymes required for viral replication: RT, IN and protease (PR) [1]. Inhibitors of these enzymes constitute the cornerstone of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [2] which provide the only means for clinically managing HIV. Particularly interesting is the RT which consists of two distinct enzymatic domains: the pol domain and the RNase H domain. The primary function of the RNase H domain is to selectively degrade the intermediate RNA/DNA heteroduplex [3]. Interestingly, while RT pol has been extensively targeted by many nucleoside RT inhibitors (NRTIs) [4] and nonnucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs) [5–7], drug discovery efforts targeting the RNase H function have not produced a single candidate in development pipeline[8]. Nevertheless, the attenuated biochemical activity of RNase H resulted from active site mutation was found to correlate closely with reduced HIV replication in cell culture[9], strongly suggesting that effective RNase H inhibition should confer the desired antiviral phenotype. Due to their unique mechanism of action, antivirals targeting RNase H are expected to inhibit HIV strains resistant to known drugs.

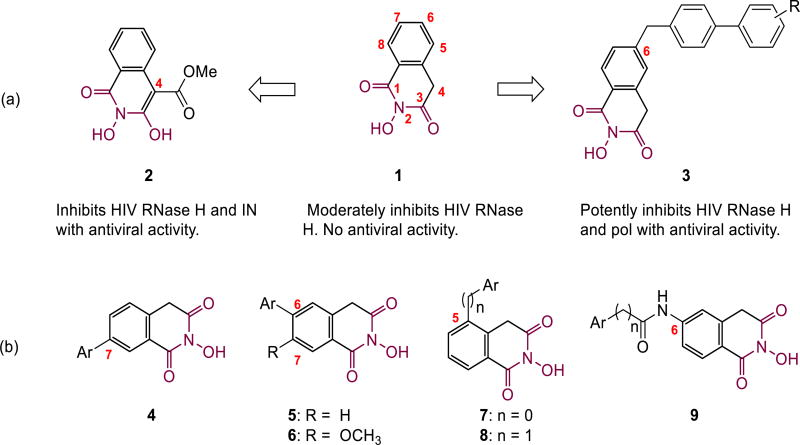

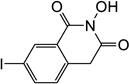

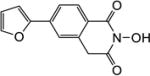

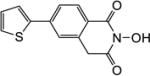

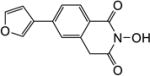

RNase H adopts an active site fold that defines a family of homologous enzymes termed retroviral integrase super family (RISF) [10]. Specifically, its catalytic function hinges on a DEDD motif at active site that can engage with two divalent metal ions.[11] Consequently, RNase H inhibition typically entails a chemical core capable of chelating two divalent metals, a pharmacophore feature shared by inhibitors of two homologous enzymes: HIV IN and HCV NS5B polymerase. The HID core contains a perfectly aligned chelating triad around its 6-membered ring (1,[11] Fig. 1a), thus has been widely explored as inhibitors of HIV RNase H (1 [11], 2 [12, 13], 3 [14], Fig. 1a), HIV IN (2[15], Fig. 1a) and HCV NS5B polymerase (4—5 [16], Fig. 1b). Given that HID subtypes have been reported to potently inhibit HIV RNase H, we were prompted to study the RNase H inhibitory activity of the two HID variants (4—5) previously reported as HCV NS5B inhibitors. Our current study also extends to previously unknown aryl substituted HID regiosiomers (6—7), 5-arylmethyl HID analogues (8) and 6-arylcarboxamide substituted HID analogues (9, Fig. 1b). Regioisomeric HID scaffold of 8 has been reported to potently inhibit HIV RNase H and pol [14], and that of 9 was found to inhibit HIV IN [12].

Figure 1.

Subtypes of HID scaffold as inhibitors of HIV RT-associated RNase H. (a) Parent HID (1), 4-carboxylated HID (2) and 6-biaryl methyl HID (3) with reported RNase H inhibitory activities; (b) Newly synthesized HID variants as potential inhibitors of HIV RNase H. Subtypes 4 and 5 were previously reported to inhibit HCV NS5B.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1 Chemistry

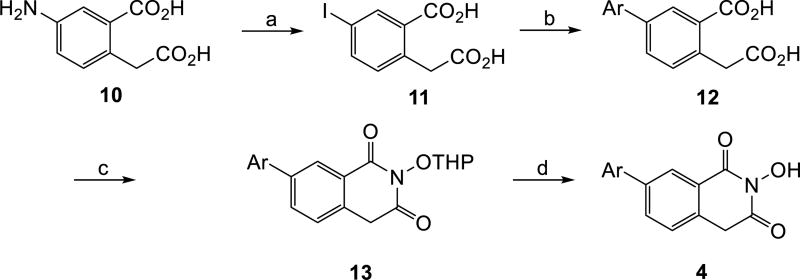

HID subtypes 4 and 5 were synthesized based on our previously reported procedures (Schemes 1–2) [16]. Both routes feature a synthetic sequence consisting of a Sandmeyer reaction [17] on an amino homophthalic acid compound (7 in Scheme 1 and 14 in Scheme 2) to prepare the iodo intermediate (8 in Scheme 1 and 15 in Scheme 2), a Suzuki coupling reaction[18] to install the aryl group (9 in Scheme 1 and 16 in Scheme 2), and a cyclization to construct the HID ring (10 in Scheme 1 and 17 in Scheme 2).

Scheme 1. a Synthesis of HID subtype 4.

aReagents and conditions: H2SO4, NaNO2, −10 °C, then urea, −10 to 0 °C, KI, rt overnight, 44%; b) ArB(OH)2, Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, H2O: EtOH, microwave, 150 °C, 30 min, 87%–quant; c) THPONH2, ClPh, CDI, reflux 30 sec.; d) p-TSA hydrate, MeOH, 6–22% over two steps.

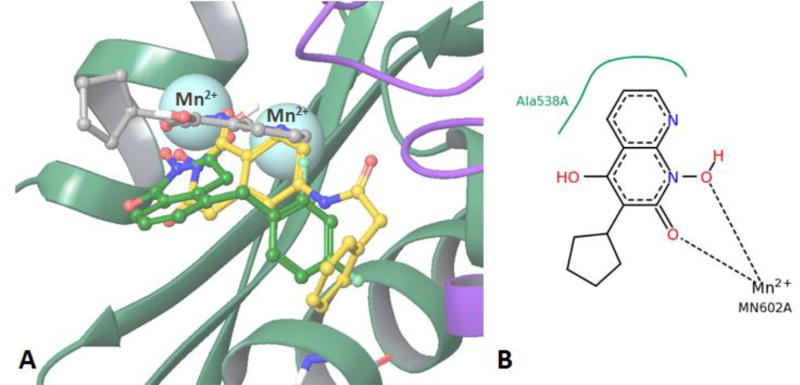

Figure 2.

Top scored docking poses of compounds 8c and 9c in the RNase H active center (3LP1[31] as a receptor). A) Structural overlap of top scored pose of 8c (green carbons), 9c (yellow carbons) and LP8 (grey carbons). B) LP8 2D structure and interaction diagram obtained from Protein Data Bank as a part of 3LP1 crystal structure. Non-polar hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

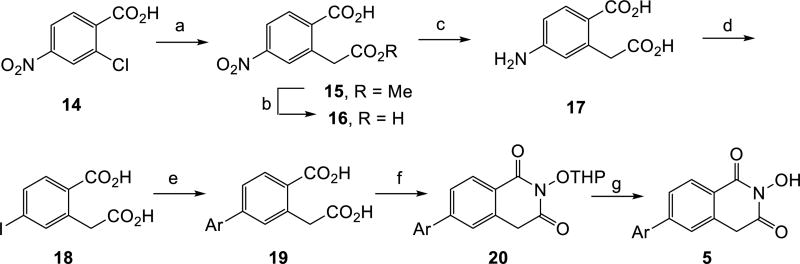

Scheme 2. aSynthesis of HID subtype 5.

aReagents and conditions: a) dimethyl malonate, CuBr, NaOMe, 92%; b) NaOH, MeOH, rt overnight, 49%; c) 10% Pd/C, H2, EtOH, 85%; d) H2SO4,, NaNO2, −10 °C, then urea, −10 to 0 °C, KI, rt overnight, 58%; e) ArB(OH)2, Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, H2O: EtOH, microwave, 150 °C, 30 min, 59%–quant.; f) THPONH2, ClPh, CDI, reflux 30 sec.; g) p-TSA hydrate, MeOH, 10–24% over two steps.

The two routes differ in that the requisite amino homophthalic acid compound 7 is commercially available for the synthesis of 7-substituted HID (subtype 4), whereas the regioisomer (14) for the synthesis of 6-substituted HID (subtype 5) was prepared in three steps featuring a Hurtley reaction [19] (Scheme 2, 11 to 12).

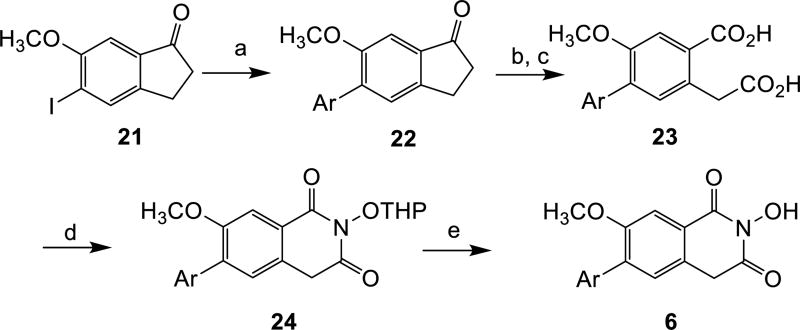

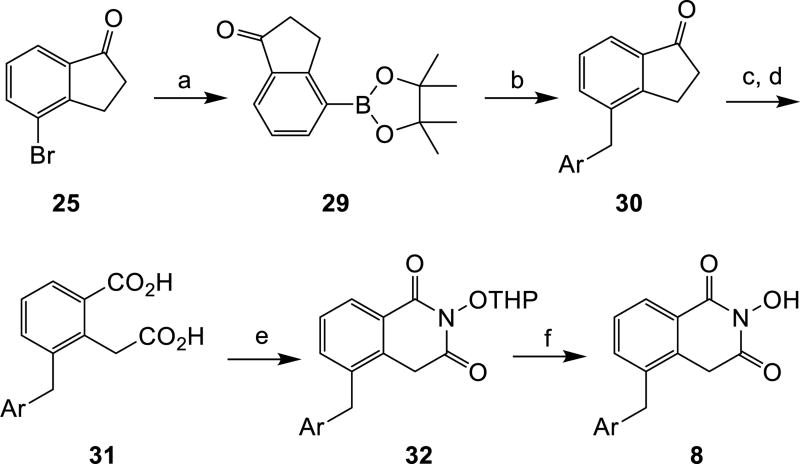

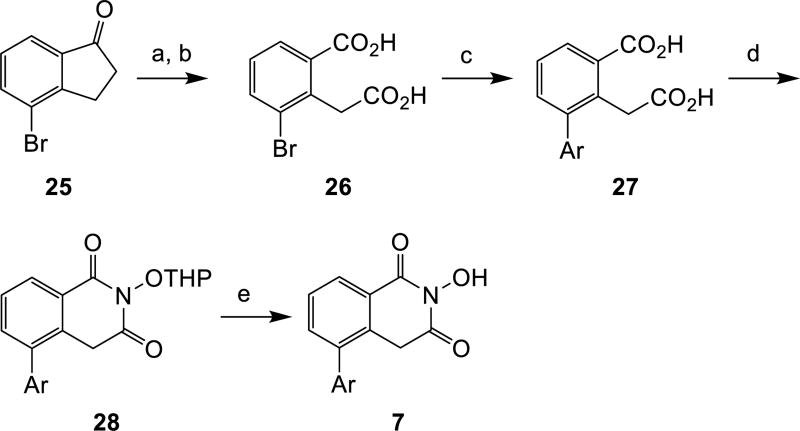

The synthesis of subtypes 6—8 all started with a halogenated indanone (21 for subtype 6 and 25 for subtypes 7—8). Following a reported procedure [20], acylation of the indanone with diethyl oxalate and the subsequent oxidation with alkaline hydrogen peroxide produced key homophthalic acid intermediates 23, 26 and 31 (Schemes 3—5). The introduction of the aryl group was carried out right before (for subtypes 6 and 8, Scheme 3 and Scheme 5) or after (for subtype 7, Scheme 4) the formation of the homophthalic acid. The construction of HID from the homophthalic acid was effected using the same synthetic sequence as for subtypes 4—5.

Scheme 3. a Synthesis of HID subtype 6.

aReagents and conditions: a) ArB(OH)2, Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, toluene: H2O, microwave, 110 °C, 35 min, 58–72%; b) diethyloxalate, NaOCH3, toluene, rt, 12 h; c) KOH, H2O2, MeOH, rt, 51–64% over two steps; d) THPONH2, CDI, toluene, reflux, 8 h; e) p-TSA hydrate, MeOH, 2–3 h, rt, 32–50% over two steps.

Scheme 5. a Synthesis of HID subtype 8.

aReagents and conditions: a) bis(pinacolato)diboron, PdCl2(dppf)2, KOAc, dioxane, microwave, 120 °C, 20 min, 76%; b) ArCH2Br, Pd(PPh3)4, Na2CO3, THF: H2O, 80 °C, 45 min, 52–66%; c) diethyloxalate, NaOCH3, toluene, rt, 12 h; d) KOH, H2O2, MeOH, rt, 45–56% over two steps; e) THPONH2, CDI, toluene, reflux, 8 h; f) p-TSA hydrate, MeOH, 2–3 h, rt, 30–44% over two steps.

Scheme 4. a Synthesis of HID subtype 7.

aReagents and conditions: a) diethyloxalate, NaOCH3, toluene, rt, 12 h; b) KOH, H2O2, MeOH, rt, 56% over two steps; c) ArB(OH)2, Pd(PPh3)4, K2CO3, EtOH: H2O, microwave, 150 °C, 30 min, 55–71%; d) THPONH2, CDI, toluene, reflux, 8 h; e) p-TSA hydrate, MeOH, 2–3 h, rt, 38–44% over two steps.

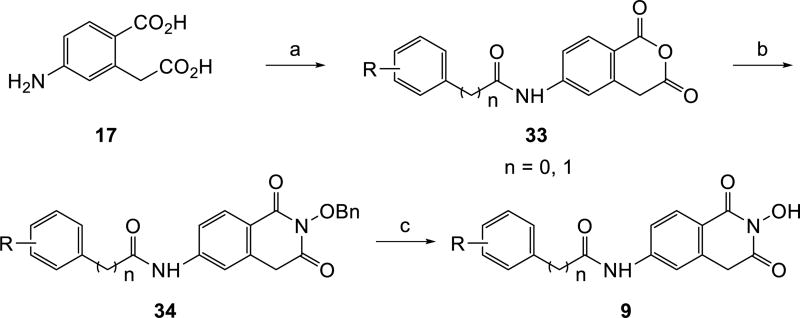

Additionally, subtype 9 in which the 6-aryl moiety is separated by an amide linkage was also prepared. C-7 regioisomers of these analogues were reported to inhibit HIV IN. The synthesis of 9 was effected via a simple acylation of the amido diacid intermediate 17 followed by the HID construction (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. a Synthesis of HID subtype 9.

a Reagents and conditions: (a) Acid chloride, refluxing, 85–98%.; (b) i. BnONH2, toluene, refluxing, overnight; ii. CDI, DMF, 100 °C 1h, 60–82%; (c) BBr3 (7.5 eq), DCM, rt, 1 h, H2O, rt. 60–80%.

2.2 Biology

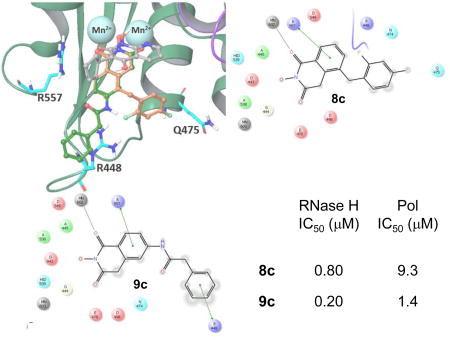

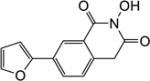

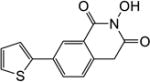

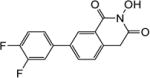

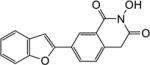

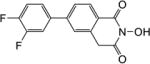

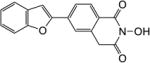

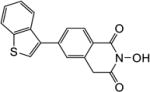

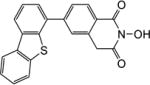

All synthesized HID analogues were evaluated for biochemical inhibition of both the RNase H and pol functions of HIV RT, and for antiviral activity in a cytoprotection assay. The RNase H assay was conducted using an 18 bp oligonucleotide duplex as described previously [14, 21]. A known inhibitor THBNH [22] was used as the positive control in all assays. This substrate measures the random and internal cleavage which is believed to represent the major mode of RNA cutting. Detailed biochemical assay results are summarized in Table 1. Overall, all HID subtypes tested (4–9) inhibited RNase H in sub to low micromolar range (IC50 = 0.20–2.0 µM). The position of the aryl substitution did not appear to impact RNase H inhibition significantly, as shown with analogues 4a (C-7, IC50 = 1.2 µM), 5a (C-6, IC50 = 1.1 µM) and 7a (C-5, IC50 = 2.0 µM). For the C-6 aryl substituted analogues, introduction of an additional methoxy group at C-7 slightly decreased RNase H inhibition (6a vs 5a, Table 1). Interestingly, for the C-5 substituted analogues, introducing a methylene linker led to increased RNase H inhibition (7c vs 8c, Table 1). It is noteworthy that three of the four subtype 8 inhibited RNase H in submicromolar range (8b–8d). The most potent RNase H inhibition, however, was observed with subtype 9. As shown in Table 1, all HID analogues with an amide linkage (9a–9d) inhibited RNase H at nanomolar concentrations (IC50 = 0.20–0.30 µM), reflecting a 5–10 fold of improvement in potency over the ones without linkage (subtypes 4–7). As for RT pol inhibition, analogues of subtypes 4–5 and 9 all potently inhibited the pol function, resulting in virtually no selectivity between RNase H and pol inhibition for 4–5, and modest selectivity for 9 (2–7 fold). A significantly lower level of RT pol inhibition was observed with subtypes 6 and 8, amounting to a selectivity of up to 6 fold and 12 fold, respectively. Two of the three analogues of subtype 7 exhibited only weak inhibition (7b and 7c, Table 1) against pol. However, their biochemical inhibition against RNase H was substantially less potent than subtypes 8–9. These results suggest that the 5-arylmethyl substituted subtype (8) and the 6-arylamido substituted subtype (9) represent the most promising scaffolds for potently and selectively inhibiting HIV RT associated RNase H, as shown with compounds 8c (IC50 = 0.8 µM, selectivity = 12 fold) and 9c (IC50 = 0.2 µM, selectivity = 7 fold) both of which inhibited HIV RNase H with comparable potency to and better selectivity than THBNH (Table 1).

Table 1.

Biochemical assay results for HID subtypes 4–9

| Compd | Structure | RNH IC50a (µM) |

pol IC50a (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4a |

|

1.2 | 1.3 |

| 4b |

|

1.7 | 2.5 |

| 4c |

|

2.0 | 2.8 |

| 4d |

|

0.90 | 1.6 |

| 4e |

|

1.4 | 1.9 |

| 5a |

|

1.1 | 1.5 |

| 5b |

|

1.7 | 1.7 |

| 5c |

|

1.4 | 2.0 |

| 5d |

|

1.3 | 2.1 |

| 5e |

|

1.1 | 1.5 |

| 5f |

|

1.1 | 1.3 |

| 5g |

|

1.8 | 1.6 |

| 5h |

|

1.2 | 1.7 |

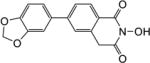

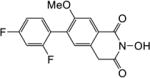

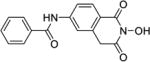

| 6a |

|

1.6 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 2.1 |

| 6b |

|

1.3 ± 0.2 | 8.1 ± 2.6 |

| 6c |

|

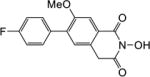

1.4 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.4 |

| 6d |

|

1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.5 |

| 7a |

|

2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.7 |

| 7b |

|

1.4 ± 0.1 | >25 |

| 7c |

|

1.5 ± 0.02 | 25 ± 1 |

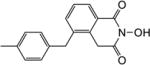

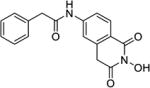

| 8a |

|

1.0 ± 0.1 | 8.0 ± 0.5 |

| 8b |

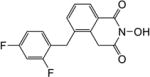

|

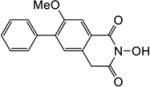

0.83 ± 0.03 | 7.4 ± 0.1 |

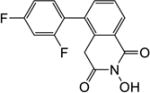

| 8c |

|

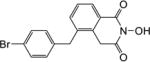

0.82 ± 0.04 | 9.3 ± 0.9 |

| 8d |

|

0.60 ± 0.07 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

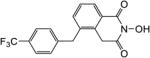

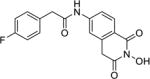

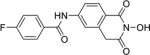

| 9a |

|

0.30 ± 0.02 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

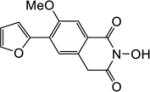

| 9b |

|

0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.05 |

| 9c |

|

0.20 ± 0.02 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| 9d |

|

0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.06 |

| THBNH | -- | 0.20 | 0.50 |

IC50: concentration of a compound producing 50% inhibition expressed as mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments for 6a–9d and as mean from two independent experiments where errors are generally within 5% for 4a–5h.

All these analogues were also screened in a previously reported cytoprotection antiviral assay [23]. Unfortunately, no significant reduction in cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed at 10 µM with any analogue described herein (data not shown).

2.3 Molecular modeling

To better understand the observed dual inhibition against RT RNase H and pol, we conducted extensive molecular modeling analysis with two representative compounds 8c and 9c to probe their predicted binding to the active sites of RNase H and pol as well as the NNRTI binding site of the pol.

RNase H active site

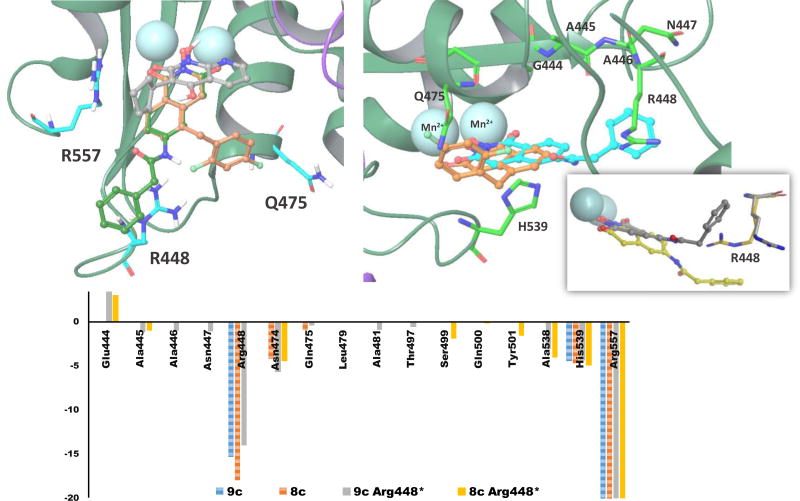

Computer modeling shows two major binding modes for compounds 8c and 9c in RNase H active center. We compare these binding modes with a position of LP8 (3-cyclopentyl-1,4-dihydroxy-1,8-naphthyridin- 2(1H)-one) co-crystallized in 3LP1 structure (Fig. 2a). Compounds 8c, 9c and LP8 all bear a chelating triad of electronegative atoms, thus similar metal coordination mode could be expected for these compounds. Structural analysis shows significant differences in the overall position of the ligands as well as in metal coordination for the first binding mode (Fig. 2) which has the highest docking scores for both compounds (−8.706 kcal/mol for 8c and −8.428 kcal/mol for 9c).

The second binding mode simulated for 8c and 9c is represented by poses with lower docking scores (−7.588 kcal/mol for 8c and −6.795 kcal/mol for 9c), but has more similarity in overall pose and metal coordination pattern to LP8 ligand (Fig. 3a). Overall docking poses and per-residue interaction scores (Fig. 3a and 3c) show that both compounds create similar contacts with surrounding amino acid side chains. Arg557 is involved in pi-pi stacking interactions with hydroxyisoquinoline rings of 8c and 9c. The phenyl ring of compound 9c also has an additional pi-pi stacking interaction with Arg448 (Fig. 3a), an interaction absent for compound 8c. Another contact, by which 8c and 9c are differ by, is Gln475 side chain which is about 2.4Å from compound 8c, but further away from 9c since the substituent amide linker and phenyl ring of 9c face opposite directions. To evaluate Arg448 contribution to overall binding of compound 9c and 8c to RNase H active center we mutated Arg448 to alanine in silico and docked both compounds to modified RT structure. RNase H active site is shallow and wide which limits contacts an active site inhibitor could make with surrounding residues while effectively chelating metal cations. Thus, elimination of bulky Arg side chain, which guanidinium group is capable for pi-pi stacking interactions with aromatic moiety of 9c, would affect binding and docking scores. Results obtained for simulations involving mutated structure were quite unexpected. For both compounds 8c and 9c lower docking scores were calculated which indicates better binding to R448A mutant. In absence of long and bulky Arg448, both compounds bound close to the loop formed by residues 444–448 and thus created more contacts which resulted in more negative docking scores (see Supplemental information). Based on this theoretical finding we allow full flexibility of Arg448 and adjacent residue side chains and re-docked both compounds into RNase H active center. This docking experiment did result in more contacts with site chain residues and more negative docking scores (Fig. 3b and 3c). Large and negative interaction scores for Arg448 and Arg557 (Fig. 3c) are due large negative Coulombic term defining interactions between positively charged Arg and negatively charged molecules of 8c and 9c. Docking into structure with flexible Arg448 side chain results in pose where less flexible compound 8c moves away from Arg448 (Fig. 3b). Besides potential for strong pi-pi stacking interaction between compound 9c and Arg448, our modeling data does not show significant superiority of 8c over 9c in binding to the RNase H active site. Thus substantial difference in RNase H inhibition is not expected. Indeed, the biochemical data for both compounds differ by less than one order of magnitude and such a difference is probably too subtle to be picked up by molecular modeling.

Figure 3.

Second binding mode obtained for 8c and 9c compounds docked into RNase H active site. A) Structural overlap of 8c (brown carbons), 9c (green carbons), and LP8 (grey carbons); B) Binding mode obtained for 9c (cyan) and 8c (brown) with adjusted Arg448 conformation. Figure insert: Crystal structure conformation of Arg448 and docked 9c (yellow) superimposed with dynamically adjusted Arg448 conformation and resulting docking pose of 9c (grey); C) Calculated per-residue interactions (as a sum of vdW and Coulombic terms; more negative scores represent more favorable stabilizing contacts) for 8c and 9c compounds docked to the RNase H active site with crystal structure conformation of Arg448 and for 8c and 9c compounds docked when Arg448 side chain was allowed to rotate (tagged “Arg448*” on a legend). Note that for data clarity active side residues Asp443, Glu478, Asp498, and Asp549 are omitted from this chart. LID for best docked poses are available in Supplemental Information.

Polymerase active site

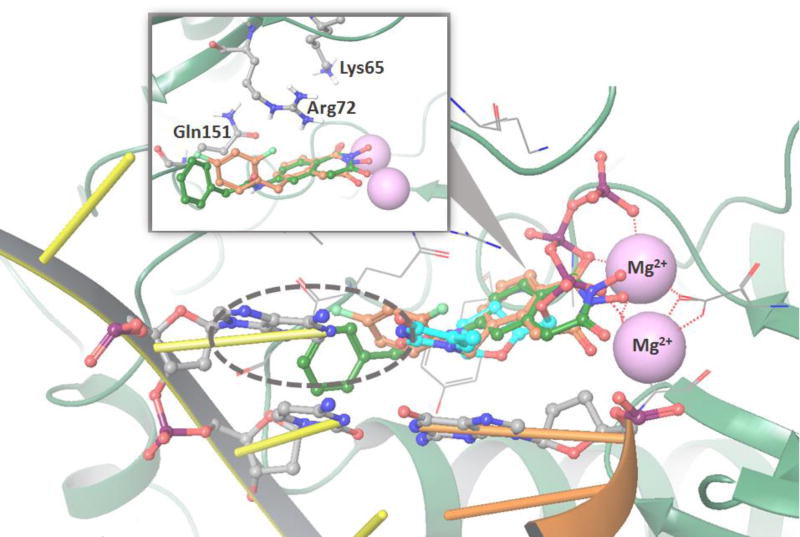

Docking results show that both compounds can bind into the RT polymerase active center without any steric hindrance (Fig. 4 insert) and close to residues Lys65, Arg72, and Gln151, residues which play key roles in the polymerization activity of HIV-1 RT.[24–27] However, for 8c and 9c in the polymerase active site, inhibition through a competitive mode of action is unlikely. In our polymerase assays, RT is pre-incubated with primer-template duplex for which RT has a substantially greater binding affinity than for small molecules such as 8c and 9c. The latter are unlikely to compete for binding with the nucleic acid duplex, and thus cannot really block the polymerase active site. Compounds 8c and 9c likely bind to the RT-primer-template complex, creating a steric clash with the template strand since 8c and 9c are longer molecules compared to the natural nucleotide substrates (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Docking of 8c and 9c in RT polymerase active site (1RTD[32] structure as a receptor). Picture insert shows overlap of best docking poses of 8c (brown carbons) and 9c (green carbons) and a proximity of Lys65, Arg72, and Gln151 which are known to be important in substrate binding. Alignment with the DNA primer/template duplex that is a part of 1RTD structure, but was initially removed for docking simulations show that there is steric clash with primer DNA strand (circled area) since 8c and 9c are longer molecules than natural substrate dTTP (cyan carbons).

NNRTI Binding Pocket

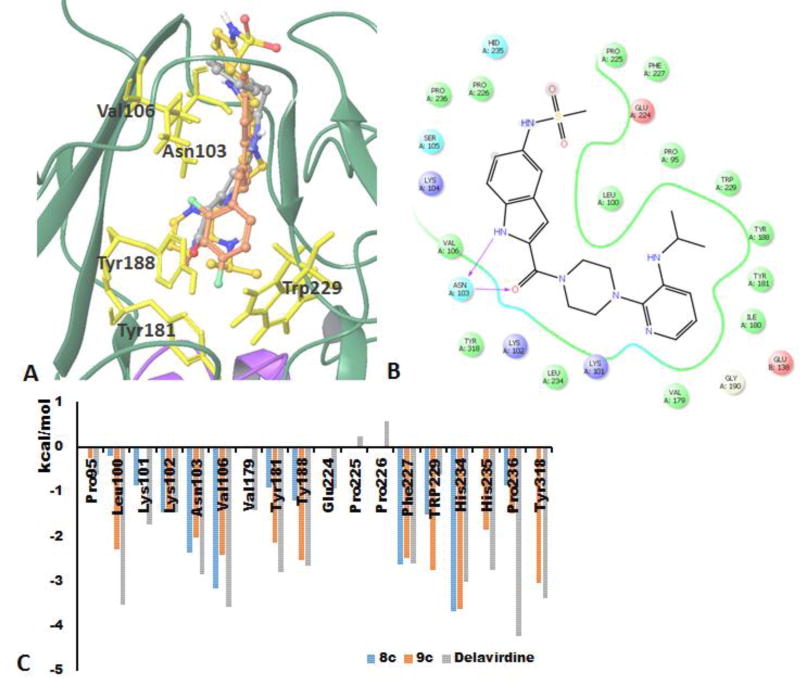

Inhibition of RT polymerase activity by compounds 8c and 9c most likely results from allosteric inhibition due to binding to NNRTI binding pocket. However, the NNRTI binding pocket presents a challenge for computational simulations since the pocket does not exist prior to inhibitor binding. NNRTIs constitute a broad variety of chemical structures, yet they all bind at the same hydrophobic allosteric pocket [5, 28, 29]. This binding extends the p66 thumb domain due to conformational changes in amino acid residues Tyr181 and Tyr188. The conformational change of RT upon NNRTI binding would be too global to be successfully picked up by present docking algorithms for induced fit binding. Thus, we considered a crystal structure in which the NNRTI pocket is already present. We chose structure 1KLM with co-crystalized delavirdine (Fig. 5b), a compound with more structural similarities to our studied compounds than other NNRTIs.

Figure 5.

Docking in NNRTI binding pocket (1KLM[33] structure as a receptor). A) Overlap of the best docking poses of delavirdine (yellow carbons), 8c (brown carbons), and 9c (grey carbons); B) LID for delavirdine best pose; C) calculated van der Waals per-residue interactions for delavirdine, 8c, and 9c.

Our modeling results show that both 8c and 9c bind better to the NNRTI pocket in protonated neutral form. Calculated docking scores for neutral 8c and 9c are −9.488 kcal/mol and −9.797 kcal/mol respectively while the best binding scores are predicted at −8.994 kcal/mol for deprotonated 8c and −8.881 kcal/mol for deprotonated 9c. Lower binding of 8c and 9c deprotonated forms could be explained by the significant hydrophobicity of the NNRTI pocket. Calculated docking scores for 8c and 9c are lower than the score calculated for delavirdine (−11.209 kcal/mol). Both 8c and 9c bind very similarly to delavirdine (Fig. 5a) in proximity to Tyr181, Tyr188, Asn103, and Trp229. Both the value of the docking scores and the larger number of van der Waals contacts (Fig. 5c) indicates that 9c interacts more strongly with residues in the NNRTI binding pocket, which corroborates the observation that 9c inhibited RT polymerase with about 10-fold greater potency than 8c. Difference in RT polymerase inhibition measured for 8c and 9c could be attributed to structural features of compound 9c which is more extended and has a more hydrophobic non-substituted phenyl ring compared with 8c, attributes that might favor hydrophobic interactions. Other crystal structures with co-crystallized NNRTIs were explored, however those docking simulations did not indicate significant interactions with side chains of Tyr181, Tyr188, Asn103, and Trp229 (additional data available in Supplemental Information).

Docking scores calculated for 8c and 9c in the NNRTI binding pocket are higher than those calculated for binding into RNase H active site, yet the RNase H inhibition of both compounds was found to be higher than the inhibition of RT polymerase. Several factors need to be taken into consideration when correlating docking scores to inhibitory activities. First, our docking experiments were performed with different RT structures, and docking scores cannot be directly compared because they were calculated for different protein receptors. Second, more negative docking scores are indicative of stronger binding; however, they also reflect number of interactions between a ligand and protein. NNRTI binding pocket and RNase H active sites are different in shape and size with NNRTI binding pocket being more confined and RNase H active site being wide and shallow. This difference is reflected in the number of contacts with 8c and 9c in RNase H active site (Fig. 3d) and NNRTI binding pocket (Fig. 5c). The key binding of metal chelation at RNase H active site is often underestimated by scoring algorithms which results in overall lower docking scores calculated when ligand-metal interactions are involved.

3. Conclusion

A few HID subtypes were synthesized and tested for their ability to inhibit HIV RT-associated RNase H. Interestingly, subtypes 4, 5 and 9 showed inhibitory activity against both the RNase H and pol of HIV RT at sub to low micromolar concentrations, whereas subtypes 6 and 8 inhibited RT with modest selectivity toward RNase H inhibition and subtype 7 predominantly inhibited RNase H. Extensive molecular modeling largely corroborated these observations. Our studies identified analogues 8c (IC50 = 0.8 µM, selectivity = 12 fold) and 9c (IC50 = 0.2 µM, selectivity = 7 fold) as potent and selective inhibitors of HIV RNase H.

4. Experimental part

4.1. General - Chemistry

All commercial chemicals were used as supplied unless otherwise indicated. Dry solvents (THF, toluene, and dioxane) were dispensed under argon from an anhydrous solvent system with two packed columns of neutral alumina or molecular sieves. Flash chromatography was performed on a Teledyne Combiflash RF-200 with RediSep columns (silica) and indicated mobile phase. All moisture sensitive reactions were performed under an inert atmosphere of ultra-pure argon with oven-dried glassware. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 600 MHz spectrometer. Mass data were acquired on an Agilent TOF II TOS/MS spectrometer capable of ESI and APCI ion sources. Analysis of sample purity was performed on a Varian Prepstar SD-1 HPLC system with a Phenomenex Gemini, 5 micron C18 column (250mm × 4.6 mm). HPLC conditions: solvent A = H2O, solvent B = MeCN; flow rate = 1.0 mL/min; compounds were eluted with a gradient of 10% MeCN/H2O to 100% MeCN for 30 min. Purity was determined by total absorbance at 254 nm. All tested compounds have a purity ≥ 98%. Compounds of subtypes 4 (4a–4e) and 5 (5a–5h) were previously reported [14].

4.1.1. General procedure 1 for Suzuki coupling 22a–22d

The mixture of 5-iodo-6-methoxy-1-indanone 21 (200 mg, 0.69 mmol), boronic acid (0.83 mmol, 1.2 equiv.), K2CO3 (2.7 mmol, 4.0 equiv.), toluene/H2O (9.5:0.5, 4.0 mL) and Pd[P(Ph)3]4 (30 mg) were microwaved at 110 ºC for 30 min. The reaction was monitored by TLC. The black residue formed was filtered and the filtrate was diluted with EtOAc. The EtOAc layer was washed with brine, the combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (EtOAc/hexane; 1:9) to afford desired compound (22a–d).

4.1.2. General procedure 2 for the synthesis of homophthalic acid derivatives 23a–23d, 26 and 31a–31d

A freshly prepared solution of sodium methoxide (2.45 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) was added dropwise to a solution of compound 22 (0.3 g, 1.22 mmol) and diethyl oxalate (1.96 mmol, 1.6 equiv.) in toluene (5 ml) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred overnight at ambient temperature. The solvent was evaporated to dryness and the residue was suspended in MeOH (4 mL) and solid KOH (7.37 mmol, 6.0 equiv.) was added portion wise keeping the temperature below 50 °C and stirred at room temperature for 3 h. Then hydrogen peroxide (30%, 12.2 mmol, 10.0 equiv.) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture keeping the temperature below 50 °C and then stirred at room temperature for 18 h. Gas was evolved during H2O2 addition. The mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was partially reduced in vacuo to remove MeOH. The remaining aqueous filtrate was washed with ether, and the organic layer was discarded. The aqueous layer was acidified with HCl until pH 2–3. The acidic aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL), the combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The crude product was recrystallized from ether to yield desired compound (23a–d), 26 and (31a–d) as a solid.

4.1.3. General procedure 3 for cyclization and deprotection 6a–6d, 7a–7c and 8a–8d

A solution of dicarboxylic acid 23 (0.1 g, 0.35 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and NH2OTHP (0.70 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) in toluene (10 mL) was refluxed for 5 minutes. To the mixture, a solution of CDI (0.28 mmol, 0.8 equiv.) in DCM was added dropwise. The suspension turned clear and stirred at reflux for 8 h, a black solid separated from solution, and the reaction monitored by TLC and MS. The reaction mixture was passed through a short pad of silica gel which then rinsed with (EtOAc/hexane; 1:3), the combined filtrate was evaporated to dryness. The product was used for the next reaction without further purification. The cyclized product was dissolved in MeOH (5.0 mL) and treated with pTSA hydrate (0.35 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and stirred at room temperature for 2–3 h. The reaction was monitored by TLC and MS. The mixture was evaporated to dryness to get pale yellow solid. The solid obtained was triturated with water and then with ether, and dried at room temperature to afford a desired pure compound (6a–d), (7a–c) and (8a–d) as a solid.

4.1.4. General procedure 4 for Suzuki coupling 27a–27c

The mixture of 6-bromo homophthalic acid 26 (0.2 g, 0.77 mmol), boronic acid (1.55 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), K2CO3 (3.1 mmol, 4.0 equiv.), EtOH/ H2O (9:1, 4.0 mL) and Pd[P(Ph)3]4 (30 mg) were microwaved at 150 °C for 30 min. The reaction was monitored by TLC. The black residue formed was filtered and the EtOH was evaporated. The aqueous layer was acidified with HCl until pH 2–3 and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The crude product was purified by recrystallization with ether/ EtOAc to afford desired compound (27a–c) as a solid.

4.1.5. Synthesis of 4-(4,4,5,5-Tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (29)

The mixture of 4-Bromo-1-indanone 25 (1.0 g, 4.7 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), bis(pinacolato)diboron (1.8 g, 7.1 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), KOAc (0.93 g, 9.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), dioxane (15 mL) and PdCl2(dppf)2 (0.1 g) were microwaved at 120 °C for 20 min. The suspension was filtered and washed with EtOAc. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was diluted with EtOAc and washed with brine, organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (EtOAc/hexane; 1:9) to afford desired compound 29 (0.93 g, 3.6 mmol, 76%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 8.04 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.34-3.33 (m, 2H), 2.73-2.66 (m, 2H), 1.29 (s, 12H).

4.1.6. General procedure 5 for Suzuki coupling 30a–30d

The mixture of boronic ester 29 (0.5 g, 1.9 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), ArCH2Br (5.8 mmol, 3.0 equiv.), Na2CO3 (3.8 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), THF/H2O (9:1, 10.0 mL) and Pd[P(Ph)3]4 (30 mg) were microwaved at 80 °C for 45 min. The reaction was monitored by TLC. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was diluted with EtOAc and washed with brine, organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (EtOAc/hexane; 1:9) to afford desired compound (30a–d).

4.1.7. 5-(Furan-2-yl)-6-methoxy-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (22a)

Yield 72%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.90 (s, 1H), 7.51 (s, 1H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.12 (s, 1H), 6.51 (s, 1H), 3.94 (s, 3H), 3.07-3.05 (m, 2H), 2.70-2.68 (m, 2H).

4.1.8. 2-(Carboxymethyl)-4-(furan-2-yl)-5-methoxybenzoic acid (23a)

Yield 51%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.43 (br, 2H), 7.79 (s, 1H), 7.66 (s, 1H), 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 6.62 (s, 1H), 3.94 (s, 3H), 3.91 (s, 2H).

4.1.9. 6-(Furan-2-yl)-2-hydroxy-7-methoxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (6a)

Yield 42%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.37 (s, 1H), 7.84 (s, 1H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.58 (s, 1H), 7.13 (s, 1H), 6.64 (s, 1H), 4.22 (s, 2H), 3.98 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.9, 161.8, 154.2, 148.5, 144.0, 127.4, 124.3, 124.1, 113.6, 112.9, 109.7, 56.3, 36.7; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C14H10NO5 272.0559 [M-H]−, found 272.0596.

4.1.10. 6-Methoxy-5-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (22b)

Yield 68%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.53-7.52 (m, 2H), 7.44-7.42 (m, 2H), 7.39-7.37 (m, 2H), 7.29 (s, 1H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.11-3.09 (m, 2H), 2.74-2.72 (m, 2H).

4.1.11. 5-(Carboxymethyl)-2-methoxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid (23b)

Yield 54%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.21 (br, 2H), 7.56 (s, 1H), 7.51-7.49 (m, 2H), 7.44-7.42 (m, 2H), 7.38-7.36 (m, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 3.91 (s, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H).

4.1.12. 2-Hydroxy-7-methoxy-6-phenylisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (6b)

Yield 32%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.21 (s, 1H), 7.59 (s, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.44-7.36 (m, 3H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 4.20 (s, 2H), 3.83 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.9, 162.0, 155.7, 137.0, 135.8, 130.2, 129.6, 128.6, 128.2, 127.4, 125.4, 109.6, 56.3, 36.7; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C16H12NO4 282.0766 [M-H]−, found 282.0798.

4.1.13. 5-(4-Fluorophenyl)-6-methoxy-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (2c)

Yield 61%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.52-7.50 (m, 2H), 7.38 (s, 1H), 7.29 (s, 1H), 7.14-7.11 (m, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.13-3.11 (m, 2H), 2.76-2.74 (m, 2H).

4.1.14. 5-(Carboxymethyl)-4’-fluoro-2-methoxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid (23c)

Yield 64%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.32 (br, 2H), 7.53-7.52 (m, 3H), 7.35 (s, 1H), 7.26-7.23 (m, 2H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.77 (s, 2H).

4.1.15. 6-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-hydroxy-7-methoxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (6c)

Yield 50%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.49 (s, 1H), 7.69 (s, 1H), 7.66-7.63 (m, 2H), 7.43 (s, 1H), 7.37 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.29 (s, 2H), 3.94 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.9, 161.9, 155.7, 134.6, 133.3, 131.7, 130.2, 127.4, 125.5, 115.6, 109.6, 56.3, 36.6; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C16H11NFO4 300.0672 [M-H]−, found 300.0712.

4.1.16. 5-(2,4-Difluorophenyl)-6-methoxy-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (22d)

Yield 58%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.35 (s, 1H), 7.30 (s, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 6.96-6.91 (m, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.12-3.11 (m, 2H), 2.76-2.75 (m, 2H).

4.1.17. 5-(Carboxymethyl)-2’,4’-difluoro-2-methoxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid (23d)

Yield 61%. 1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (s, 1H), 7.21 (s, 1H), 7.17-7.16 (m, 1H), 3.89 (s, 2H), 3.78 (s, 3H).

4.1.18. 6-(2,4-Difluorophenyl)-2-hydroxy-7-methoxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (6d)

Yield 39%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.41 (s, 1H), 7.61 (s, 1H), 7.43-7.39 (m, 1H), 7.34-7.30 (m, 1H), 7.28 (s, 1H), 7.17 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.19 (s, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.8, 161.9, 156.1, 133.0, 130.8, 129.5, 127.2, 126.4, 121.3, 111.9, 109.3, 104.5, 56.4, 36.6; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C16H10NF2O4 318.0578 [M-H]−, found 318.0607.

4.1.19. 3-Bromo-2-(carboxymethyl)benzoic acid (26)

Yield 56%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.61 (br, 2H), 7.61-7.58 (m, 2H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.36 (s, 2H).

4.1.20. 2-(Carboxymethyl)-3-(furan-2-yl)benzoic acid (27a)

Yield 71%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.61 (br, 2H), 7.86 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (s, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (s, 2H), 4.04 (s, 2H).

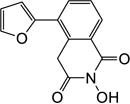

4.1.21. 5-(Furan-2-yl)-2-hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (7a)

Yield 41%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.42 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (s, 1H), 7.56 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (s, 2H), 6.67 (s, 2H), 4.33 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.1, 162.0, 150.8, 144.0, 131.8, 130.7, 128.9, 128.1, 127.8, 126.8, 112.5, 111.0, 37.3; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C13H8NO4 242.0453 [M-H]−, found 242.0483.

4.1.22. 2-(Carboxymethyl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (27b)

Yield 55%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.41 (br, 2H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.43-7.42 (m, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.91 (s, 2H).

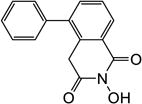

4.1.23. 2-Hydroxy-5-phenylisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (7b)

Yield 44%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.44 (s, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.56-7.53 (m, 2H), 7.49-7.47 (m, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.02 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.3, 162.2, 140.8, 139.0, 134.9, 132.3, 129.3, 129.0, 128.3, 128.0, 127.7, 126.1, 37.0; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C15H10NO3 252.0661 [M-H]−, found 252.0697.

4.1.24. 2-(Carboxymethyl)-2’,4’-difluoro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (27c)

Yield 63%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.41 (br, 2H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.36-7.35 (m, 2H), 7.31-7.29 (m, 2H), 3.91 (s, 2H).

4.1.25. 5-(2,4-Difluorophenyl)-2-hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (7c)

Yield 38%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.47 (s, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (s, 2H), 7.47-7.41 (m, 2H), 7.24 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.0, 162.0, 157.7, 135.7, 133.6, 133.4, 128.5, 128.0, 126.3, 104.9, 36.4; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C15H8NF2O3 288.0472 [M-H]−, found 288.0506.

4.1.26. 4-(4-Methylbenzyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (30a)

Yield 66%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.65 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.01 (s, 2H), 2.99-2.97 (m, 2H), 2.67-2.65 (m, 2H), 2.32 (s, 3H).

4.1.27. 2-(Carboxymethyl)-3-(4-methylbenzyl)benzoic acid (31a)

Yield 51%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.43 (br, 2H), 7.71 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.30-7.27 (m, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 3.90 (s, 2H), 2.28 (s, 3H).

4.1.28. 2-Hydroxy-5-(4-methylbenzyl)isoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (8a)

Yield 39%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.36 (s, 1H), 7.94-7.92 (m, 1H), 7.43-7.42 (m, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.05 (s, 2H), 3.97 (s, 2H), 2.24 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.3, 162.2, 139.2, 136.1, 135.7, 134.9, 133.3, 129.6, 129.1, 127.8, 126.5, 126.0, 37.2, 35.6, 21.0; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C17H14NO3 280.0974 [M-H]−, found 280.0995.

4.1.29. 4-(4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (30b)

Yield 62%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.62 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.31-7.29 (m, 2H), 7.21-7.18 (m, 2H), 4.04 (s, 2H), 2.89-2.87 (m, 2H), 2.61-2.59 (m, 2H).

4.1.30. 2-(Carboxymethyl)-3-(4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)benzoic acid (31b)

Yield 56%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.39 (br, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.49-7.48 (m, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.13 (s, 2H), 3.90 (s, 2H).

4.1.31. 2-Hydroxy-5-(4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)isoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (8b)

Yield 44%. 1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ 8.11 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.50-7.48 (m, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.84 (s, 2H), 4.17 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.6, 162.3, 143.4, 137.7, 135.1, 132.6, 129.0, 128.6, 127.5, 126.8, 125.6, 125.2, 125.1, 48.1, 37.2; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C17H11NF3O3 334.0691 [M-H]−, found 343.0724.

4.1.32. 4-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (30c)

Yield 58%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.67 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.35-7.32 (m, 2H), 7.05-7.02 (m, 1H), 6.84-6.80 (m, 2H), 4.01 (s, 2H), 3.03-3.01 (m, 2H), 2.70-2.68 (m, 2H).

4.1.33. 2-(Carboxymethyl)-3-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)benzoic acid (31c)

Yield 49%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.41 (br, 2H), 7.73 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.31-7.26 (m, 2H), 7.22-7.24 (m, 1H), 7.05-7.02 (m, 1H), 6.98-6.96 (m, 1H), 3.99 (s, 2H), 3.94 (s, 2H).

4.1.34. 5-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-2-hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (8c)

Yield 36%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.39 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.25-7.20 (m, 2H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.14 (s, 2H), 4.00 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.3, 162.2, 160.0, 137.4, 134.1, 133.4, 132.6, 132.5, 127.9, 126.8, 126.0, 122.3, 122.1, 112.2, 104.5, 104.2, 35.5, 30.3; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C16H10NF2O3 302.0629 [M-H]−, found 302.0654.

4.1.35. 4-(4-Bromobenzyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (30d)

Yield 52%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ 7.60 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.29-7.27 (m, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 2.89-2.87 (m, 2H), 2.60-2.58 (m, 2H).

4.1.36. 3-(4-Bromobenzyl)-2-(carboxymethyl)benzoic acid (31d)

Yield 45%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 12.81 (br, 1H), 12.09 (br, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 3.98 (s, 2H), 3.87 (s, 2H).

4.1.37. 5-(4-Bromobenzyl)-2-hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (8d)

Yield 30%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz) δ 10.38 (s, 1H), 7.95 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.44-7.43 (m, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.05 (s, 2H), 4.00 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz) δ 166.3, 162.2, 138.8, 138.5, 135.0, 133.4, 131.9, 131.5, 127.9, 126.7, 126.1, 119.8, 36.9, 35.6; HRMS-ESI(−) m/z calcd for C16H11NBrO3 343.9922 [M-H]−, found 343.9956.

4.1.38. General procedure for the preparation of homophthalic anhydrides (33)

[10] To homophthalic acid 17 [16] (150 mg, 0.77 mmol) in round bottom flask was added substituted benzoyl chloride (6.15 mmol, 8 equiv). This reaction mixture was heated under refluxing for 1.5 h then cooled to room temperature. The precipitate was filtered and washed with ether and cold methanol to give the desired compounds.

4.1.39. 6-((4-Fluorobenzyl)amino)isochroman-1,3-dione (33a)

Yield: 85%. 1HNMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ10.61 (s, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H); MS (ESI−) m/z: 284.26.

4.1.40. N-(1,3-Dioxoisochroman-6-yl)-4-fluorobenzamide (33b)

Yield: 98%. 1HNMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.13 (s, 1H), 7.96 (m, 2H), 7.78 (m, 2 H), 7.65 (s, 1H), 7.51 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 3.98 (s, 2H); MS (ESI−) m/z: 298.25.

4.1.41. 6-(Benzylamino)isochroman-1,3-dione (33c)

Yield: 96%. 1HNMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (s, 1H), 7.25 (m, 4H), 7.16 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 3.89 (s, 2H), 3.61 (s, 2H); MS (ESI−) m/z: 266.28.

4.1.42. N-(1,3-Dioxoisochroman-6-yl)benzamide (33d)

Yield: 95%. 1HNMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.12 (s, 1H), 7.94 (m, 3H), 7.81 (m, 1H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.59 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.98 (s, 2H); MS (ESI−) m/z: 280.26.

4.1.43. General procedure for the synthesis of 34 derivatives

A solution of 33a (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) and O-benzyl hydroxylamine (53 mg, 0.42 mmol, 1.2 equiv) in toluene 120 mL was heated under refluxing overnight. Solvent was removed and the residue was re-dissolved in DMF. To this solution was added CDI (64 mg, 1.1 equiv), and the resulting mixture was heated at 100 °C for 1 hour, then cooled to rt. The solvent was removed and the residue was purified by column chromatography to give desired compounds.

4.1.44. 2-(Benzyloxy)-6-((4-fluorobenzyl)amino)isoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (34a)

Yield: 60%. 1HNMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.89 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J =9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (s, 1H), 7.26 (m, 7H), 6.95 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 3.58 (s, 2H), 3.71 (s, 2H); MS (ESI−) m/z: 389.41.

4.1.45. N-(2-(Benzyloxy)-1,3-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-6-yl)-4-fluorobenzamide (34b)

Yield: 80%. 1HNMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.70 (s, 1H), 8.05 (m, 2H), 7.89 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.41 (m, 7H), 4.78 (s, 2H), 3.76 (s, 2H); MS (ESI−) m/z: 403.39

4.1.46. 6-(Benzylamino)-2-(benzyloxy)isoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-dione (34c)

Yield: 82%. 1HNMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.89 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.66 (s, 1H), 7.50 (m, 3H), 7.28 (m, 6H), 7.16 (m, 1H), 4.98 (s, 2H), 3.62 (s, 2H); MS (ESI−) m/z: 371.42.

4.1.47. N-(2-(Benzyloxy)-1,3-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-6-yl)benzamid (34d)

Yield: 74 %. 1HNMR (600 MHz, DMSO- d6) δ 10.70 (s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 8.05 (m, 2H), 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.94 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (m, 4H), 7.50 (m, 3H), 5.11 (s, 2H), 4.37 (s, 2H), MS (ESI−) m/z: 386.40

4.1.48. General procedure for the synthesis of9 derivatives

Compounds 34b (40 mg, 0.1 mmol) was dissolved in 0.5 mL of CH2Cl2, and boron tribromide (1.0 M solution in CH2Cl2, 7.5 mL, 0.75 mmol) was added dropwise at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred for1 hour at rt (reaction was followed by TLC analysis) and quenched by adding 2 mL of H2O dropwise. The resulting precipitate was filtered, washed with H2O and cold ether. The crude products were recrystallized in methanol to give desired compounds.

4.1.49. 2-(4-Fluorophenyl)-N-(2-hydroxy-1,3-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-6-yl)acetamide (9a)

Yield: 80 %. 1HNMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.06 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.18 (s, 2H), 3.69 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.2, 166.7, 161.7, 144.0, 136.3, 132.131.5, 131.4, 120.2, 118.2, 117.0, 115.6, 115.4, 42.8, 37.5; HRMS (ESI−) calcd. for C17H12FN2O4 [M-H]− 327.0978 found 327.0977.

4.1.50. 4-Fluoro-N-(2-hydroxy-1,3-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-6-yl)benzamide (9b)

Yield: 75%; 1HNMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.05 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (m, 1H), 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (m, 1H), 7.14 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.13 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.7, 161.7,161.8, 144.0, 136.1, 133.1, 131.0, 129.2, 120.5, 119.3, 118.1, 116.0, 115.8, 37.6; HRMS (ESI−) calcd. for C16H10FN2O4 [M-H]− 313.0824 found 313.0824.

4.1.51. N-(2-Hydroxy-1,3-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-6-yl)-2-phenylacetamide (9c)

Yield: 67%. 1HNMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.97 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (s, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (m, 4H), 7.20 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (s, 2H), 3.62 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.3, 166.7, 161.8, 144.0, 136.3, 136.0, 129.5, 129.3, 128.7, 127.1, 120.1, 118.2, 117.0, 43.8, 37.4; HRMS (ESI−) calcd. for C17H13N2O4 [M-H]− 309.1110, found 309.1112.

4.1.52. N-(2-Hydroxy-1,3-dioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-6-yl)benzamide (9d)

Yield: 60%. 1HNMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.40 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 8.23 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.53 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO--d6) δ 172.7, 168.1, 166.3, 138.1, 133.3, 132.2, 132.0, 129.7, 129.0, 128.8, 128.2, 123.8, 118.5, 40.8; HRMS (ESI−) calcd. for C16H11N2O4 [M-H]− 295.1057 found 295.1055.

4.2. Biology

4.2.1. RNase H assay

RNase H activity was measured essentially as previously described.[14, 21] Full-length HIV RT was incubated with the RNA/DNA duplex substrateHTS-1 (RNA 5’-gaucugagccugggagcu-3’-fluorescein annealed to DNA 3’-CTAGACTCGGACCCTCGA-5’-Dabcyl), a high sensitivity duplex that assesses non-specific internal cleavage of the RNA strand.

4.2.2. HIV-1 cytoprotection assay [23]

The HIV Cytoprotection assay used CEM-SS cells and the IIIB strain of HIV-1. Briefly virus and cells were mixed in the presence of test compound and incubated for 6 days. The virus was pre-titered such that control wells exhibit 70 to 95% loss of cell viability due to virus replication. Therefore, antiviral effect or cytoprotection was observed when compounds prevent virus replication. Each assay plate contained cell control wells (cells only), virus control wells (cells plus virus), compound toxicity control wells (cells plus compound only), compound colorimetric control wells (compound only) as well as experimental wells (compound plus cells plus virus).

4.3. Molecular modeling

All modeling experiments were done employing Schrodinger Small Molecule Discovery Suite.[30]

4.3.1. Small Molecules

2D structures of compounds 8c and 9c were prepared with the LigPrep™ module, which converts 2D structures to 3D, performs energy minimization, and predicts protonated and deprotonated states at physiological pH based on calculated pKa values for ionizable hydrogens. For both studied compounds pKa for the hydroxyl attached to nitrogen atom was predicted to be around 7.07±1 pH unit, which indicates that both protonated and deprotonated forms of 8c and 9c will likely be present at physiological pH. However, in chelating divalent cations in active center the deprotonated form will be more effective due to negative charge and better availability of oxygen lone pairs to overlap with metal orbitals. Thus deprotonated forms of 8c and 9c were used for docking into active sites. For docking into non-nucleoside RT inhibitor (NNRTI) binding pocket both deprotonated and protonated forms were tested. For both compounds in protonated and deprotonated forms conformers were generated using advanced conformational search implemented in ConfiGen™ module. All obtained conformers were subjected to docking into RNase H active center, poly active center, and NNRTI binding pocket.

4.3.2. Protein Receptors

Selected HIV-1 RT structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank. To add hydrogen atoms, minimize energy, and create appropriate protonation states of amino acid side chains the Protein Preparation Wizard ™ module was used. Docking grid was centered on co-crystallized ligands. Van der Waals radii of non-polar atoms were scaled by 0.8 scaling factor to account for some flex ability of protein backbone and amino acid side chains. 3LP1[31] crystal structure was used as a receptor for dicking to RNase H active site. Docking to polymerase active site was carried out with 1RTD[32] structure. This structure contains RNase H active site inhibitor. RT structure 1KLM[33] served as a receptor for docking into NNRTI binding pocket.

4.3.3. Docking

Docking simulations were performed with Glide ™ docking algorithm at standard precision. Coulombic and van der Waals interactions of 8c, 9c and delavirdine with individual amino acid residues were calculated. Ligand poses with the most negative docking scores were chosen for further analysis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

HID subtypes were synthesized and tested against HIV RT-associated RNase H and pol.

Subtypes4, 5 and 9 inhibited both RNase H and pol whereas 6–8 selectively inhibited RNase H.

Compounds8c (IC50 = 0.8 µM, selectivity = 12 fold) and 9c (IC50 = 0.2 µM, selectivity = 7 fold) were identified as potent and selective inhibitors of HIV RNase H.

Extensive molecular modeling largely corroborated observed inhibitory activities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (AI100890 to SGS, MAP and ZW), and by the Research Development and Seed Grant Program of the Center for Drug Design, University of Minnesota.

Abbreviations

- HIV

immunodeficiency virus

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- RNase H

ribonuclease H

- HID

2-hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3-dione

- IN

integrase

- Pol

polymerase

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- Pol

polymerase

- PR

protease

- HAART

highly active antiretroviral therapy

- NRTI

nucleoside RT inhibitor

- NNRTI

nonnucleoside RT inhibitor

- RISF

retroviral integrase super family

- LID

ligand interaction diagram

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Additional docking data for compounds 8c and 9c. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at t http://dx.doi.org

References

- 1.Freed EO. HIV-1 replication. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 2001;26(1–6):13–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1021070512287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Services DoHaH. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. 2015 Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents., http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- 3.Sarafianos SG, Marchand B, Das K, Himmel DM, Parniak MA, Hughes SH, Arnold E. Structure and function of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: molecular mechanisms of polymerization and inhibition. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385(3):693–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cihlar T, Ray AS. Nucleoside and nucleotide HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors: 25 years after zidovudine. Antiviral Res. 2010;85(1):39–58. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bethune MP. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), their discovery development, and use in the treatment of HIV-1 infection: a review of the last 20 years (1989–2009) Antiviral Res. 2010;85(1):75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu ZL, Guo JM, Yang Y, Zhang MD, Ba MY, Li ZZ, Cao YL, He RC, Yu M, Zhou H, Li XX, Huang XS, Guo Y, Guo CB. 2,4,5-Trisubstituted thiazole derivatives as HIV-1 NNRTIs effective on both wild-type and mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: Optimization of the substitution of positions 4 and 5. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;123:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon P, Baszczynski O, Saman D, Stepan G, Hu E, Lansdon EB, Jansa P, Janeba Z. Novel (2,6-difluorophenyl)(2-(phenylamino)pyrimidin-4-yl) methanones with restricted conformation as potent non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors against HIV-1. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;122:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilina T, Labarge K, Sarafianos SG, Ishima R, Parniak MA. Inhibitors of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase-Associated Ribonuclease H Activity. Biology. 2012;1(3):521–541. doi: 10.3390/biology1030521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parniak MP. unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nowotny M. Retroviral integrase superfamily: the structural perspective. EMBO rep. 2009;10(2):144–151. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klumpp K, Hang JQ, Rajendran S, Yang YL, Derosier A, In PWK, Overton H, Parkes KEB, Cammack N, Martin JA. Two-metal ion mechanism of RNA cleavage by HIV RNase H and mechanism-based design of selective HIV RNase H inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(23):6852–6859. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Billamboz M, Bailly F, Barreca ML, De Luca L, Mouscadet JF, Calmels C, Andreola ML, Witvrouw M, Christ F, Debyser Z, Cotelle P. Design Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of a Series of 2-Hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-diones as Dual Inhibitors of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Integrase and the Reverse Transcriptase RNase H Domain. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51(24):7717–7730. doi: 10.1021/jm8007085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billamboz M, Bailly F, Lion C, Calmels C, Andreola ML, Witvrouw M, Christ F, Debyser Z, De Luca L, Chimirri A, Cotelle P. 2-Hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-diones as inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase and reverse transcriptase RNase H domain: Influence of the alkylation of position 4. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46(2):535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernekar SK, Liu Z, Nagy E, Miller L, Kirby KA, Wilson DJ, Kankanala J, Sarafianos SG, Parniak MA, Wang Z. Design synthesis, biochemical, and antiviral evaluations of C6 benzyl and C6 biarylmethyl substituted 2-hydroxylisoquinoline-1,3-diones: dual inhibition against HIV reverse transcriptase-associated RNase H and polymerase with antiviral activities. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58(2):651–664. doi: 10.1021/jm501132s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Billamboz M, Suchaud V, Bailly F, Lion C, Demeulemeester J, Calmels C, Andreola ML, Christ F, Debyser Z, Cotelle P. 4-Substituted 2-Hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-diones as a Novel Class of HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4(7):41–46. doi: 10.1021/ml400009t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YL, Tang J, Kesler MJ, Sham YY, Vince R, Geraghty RJ, Wang ZQ. The design, synthesis and biological evaluations of C-6 or C-7 substituted 2-hydroxyisoquinoline-1,3-diones as inhibitors of hepatitis C virus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20(1):467–479. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgson HH. The Sandmeyer reaction. Chem. Rev. 1947;40(2):251–277. doi: 10.1021/cr60126a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Organoboron Compounds. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:2457–2483. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aalten HL, Vankoten G, Goubitz K, Stam CH. The Hurtley Reaction. Synthesis 1 Characterization of Copper(I) Benzoates Containing Reactive Ortho C-Cl C-Br Bonds, Their Reactivity toward Organocopper(I) Compounds - Crystal-Structure of a Thermally Stable Trinuclear Hetero Copper(I) Cluster Bis(Benzoato)Mesityltricopper(I) Organometallics. 1989;8(10):2293–2299. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang BR, Wang J, Li H, Li Y, Mei QB, Zhang SQ. Synthesis and antitumor activity evaluation of 2-arylisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-diones in vitro and in vivo. Med. Chem. Res. 2014;23(3):1340–1349. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parniak MA, Min KL, Budihas SR, Le Grice SF, Beutler JA. A fluorescence-based high-throughput screening assay for inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus-1 reverse transcriptase-associated ribonuclease H activity. Anal. Biochem. 2003;322(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Himmel DM, Sarafianos SG, Dharmasena S, Hossain MM, McCoy-Simandle K, Ilina T, Clark AD, Knight JL, Julias JG, Clark PK, Krogh-Jespersen K, Levy RM, Hughes SH, Parniak MA, Arnold E. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase structure with RNase H inhibitor dihydroxy benzoyl naphthyl hydrazone bound at a novel site. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006;1(11):702–712. doi: 10.1021/cb600303y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garforth SJ, Lwatula C, Prasad VR. The lysine 65 residue in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase function and in nucleoside analog drug resistance. Viruses. 2014;6(10):4080–4094. doi: 10.3390/v6104080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh K, Marchand B, Kirby KA, Michailidis E, Sarafianos SG. Structural Aspects of Drug Resistance and Inhibition of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase. Viruses. 2010;2(2):606–638. doi: 10.3390/v2020606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das K, Bandwar RP, White KL, Feng JY, Sarafianos SG, Tuske S, Tu X, Clark AD, Jr, Boyer PL, Hou X, Gaffney BL, Jones RA, Miller MD, Hughes SH, Arnold E. Structural basis for the role of the K65R mutation in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase polymerization, excision antagonism, and tenofovir resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(50):35092–35100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das K, Arnold E. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and antiviral drug resistance. Part 1, Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013;3(2):111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esnouf R, Ren J, Ross C, Jones Y, Stammers D, Stuart D. Mechanism of inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by non-nucleoside inhibitors. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2(4):303–308. doi: 10.1038/nsb0495-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das K, Sarafianos SG, Clark AD, Jr, Boyer PL, Hughes SH, Arnold E. Crystal structures of clinically relevant Lys103Asn/Tyr181Cys double mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in complexes with ATP and non-nucleoside inhibitor HBY 097. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;365(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrödinger, Schrödinger Suite 2014-3 Protein Preparation Wizard; Epik, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2014; Impact, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2014; Prime, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2014; LigPrep, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2014; ConfGen, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2014; Glide, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2014, 2014

- 31.Su H-P, Yan Y, Prasad GS, Smith RF, Daniels CL, Abeywickrema PD, Reid JC, Loughran HM, Kornienko M, Sharma S, Grobler JA, Xu B, Sardana V, Allison TJ, Williams PD, Darke PL, Hazuda DJ, Munshi S. Structural Basis for the Inhibition of RNase H Activity of HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase by RNase H Active Site-Directed Inhibitors. J. Virol. 2010;84(15):7625–7633. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00353-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang H, Chopra R, Verdine GL, Harrison SC. Structure of a covalently trapped catalytic complex of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: implications for drug resistance. Science. 1998;282(5394):1669–1675. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esnouf RM, Ren J, Hopkins AL, Ross CK, Jones EY, Stammers DK, Stuart DI. Unique features in the structure of the complex between HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and the bis(heteroaryl)piperazine (BHAP) U-90152 explain resistance mutations for this nonnucleoside inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94(8):3984–3989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.