Key Points

Question

What is the value of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in noninvasive risk stratification of adults with tetralogy of Fallot?

Findings

In this study, the optimal cardiovascular magnetic resonance thresholds for ventricular function were right ventricular ejection fraction less than 30% and left ventricular ejection fraction less than 45%, and they were independently predictive of death and ventricular arrhythmias. These independently predictive thresholds may be implemented in noninvasive risk stratification combined with the noninvasive components of the Khairy et al risk model.

Meaning

In patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot, right ventricular ejection fraction less than 30% and left ventricular ejection fraction less than 45% may be implemented in noninvasive risk stratification.

Abstract

Importance

Adults late after total correction of tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) are at risk for major complications. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is recommended to quantify right ventricular (RV) and left ventricular (LV) function. However, a commonly used risk model by Khairy et al requires invasive investigations and lacks CMR imaging to identify high-risk patients.

Objective

To implement CMR imaging in noninvasive risk stratification to predict major adverse clinical outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter study included 575 adult patients with TOF (4.083 patient-years at risk) from a prospective nationwide registry in whom CMR was performed. This study involved 5 tertiary referral centers with a specialized adult congenital heart disease unit. Multivariable Cox hazards regression analysis was performed to determine factors associated with the primary end point. The CMR variables were combined with the noninvasive components of the Khairy et al risk model, and the C statistic of the final noninvasive risk model was determined using bootstrap sampling. The data analysis was conducted from January to December 2016.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The composite primary outcome was defined as all-cause mortality or ventricular arrhythmia, defined as aborted cardiac arrest or documented ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia (lasting ≥30 seconds or recurrent symptomatic).

Results

Of the 575 patients with TOF, 57% were male, and the mean (SD) age was 31 (11) years. During a mean (SD) follow-up of 7.1 (3.5) years, the primary composite end point occurred in 35 patients, including all-cause mortality in 13 patients. Mean (SD) RV ejection fraction (EF) was 44% (10%), and mean (SD) LV EF was 53% (8%). There was a correlation between RV EF and LV EF (R, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.29-0.44; P < .001). Optimal thresholds for ventricular function (RV EF <30%: hazard ratio, 3.90; 95% CI, 1.84-8.26; P < .001 and LV EF <45%: hazard ratio, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.57-6.65; P = .001) were independently predictive in multivariable analysis. Both thresholds were included in a point-based noninvasive risk model (C statistic, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63-0.85) and combined with the noninvasive components of the Khairy et al risk model.

Conclusions and Relevance

In patients with repaired TOF, biventricular dysfunction on CMR imaging was associated with major adverse clinical outcomes. The quantified thresholds (RV EF <30% and LV EF <45%) may be implemented in noninvasive risk stratification.

This study uses cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in noninvasive risk stratification to predict major adverse clinical outcomes in patients with tetralogy of Fallot.

Introduction

Currently, survival into the fourth or fifth decade after repair of tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is common owing to advancements in the surgical and medical management. Nonetheless, cardiovascular morbidity remains substantial and includes an increased risk for life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden death. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is considered the golden standard in quantifying right ventricular (RV) and left ventricular (LV) volume and function. Although RV and/or LV dysfunction have been linked to adverse events, it remains unclear which thresholds can be used in risk stratification. In addition, the commonly used risk model by Khairy et al includes 2 invasive risk factors (inducible sustained ventricular tachycardia [VT] and LV end-diastolic pressure ≥12 mm Hg) but no CMR parameters. Therefore, we sought to identify valid thresholds for RV and LV function to predict major adverse events and to implement these in a noninvasive risk model, combined with the noninvasive risk factors proposed by Khairy et al.

Methods

Cohort and Methods

For this retrospective, multicenter cohort study, we identified all adult patients with surgically repaired TOF enrolled in the nationwide Congenital Corvitia (CONCOR) registry, within 1 of 5 participating centers. The data analysis was conducted from January to December 2016. Inclusion criteria consisted of (1) repaired TOF with pulmonary stenosis or atresia and (2) completed CMR examination more than 6 months before last follow-up. Medical records were reviewed to obtain patient, clinical, and surgical data. The CONCOR registry was approved by the ethics board of all participating centers and all patients provided informed consent. The need to obtain institutional review board approval for this current analysis was waived as patients were not subject to procedures or required to follow rules of behavior.

Locally performed CMR imaging data, closest to CONCOR inclusion, were obtained. Patients in whom quantitative assessment could not be performed reliably in at least 1 ventricle were excluded from this study. Trabeculations were included in the blood pool and the RV outflow tract was included as part of the RV volumes.

Follow-up time started at the date of baseline CMR or at the CONCOR registry inclusion date when CMR was performed prior to inclusion. The composite primary outcome was defined as all-cause mortality or ventricular arrhythmia, defined as aborted cardiac arrest or documented ventricular fibrillation, sustained VT lasting 30 seconds or longer, or recurrent documented symptomatic nonsustained VT requiring intervention such as cardioversion or ablation therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented using frequencies and percentages when categorical, and mean and SD or median and interquartile range when continuous. Multivariable Cox hazards regression models were used to test the change in C statistic and the 2-category net reclassification improvement (NRI) (at cutoff on 5-year event rate) of different models. The NRI was calculated after estimating 5-year survival probability (according to different models) for all patients, and dichotomizing at event rate. This method assesses the ability of the extended model to appropriately reclassify patients with and without the primary end point to high/low risk. In addition, the 2-category NRI was used similarly to select optimal thresholds for RV and LV dysfunction in multivariable models correcting for noninvasive components of the Khairy et al risk score. Finally, points were attributed to the components of the final noninvasive model, as previously proposed by Khairy et al. The C statistic of the final point-based noninvasive model was determined in 1000 bootstrap samples with replacement of cases. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM) and R version 3.3.1 (R core team).

Results

Of 755 patients with repaired TOF enrolled in the CONCOR registry within the participating centers, 575 patients (57% male; mean [SD] age, 31 [11] years; 7% pulmonary atresia) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and comprised the study population (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients (n = 575) |

Event (n = 35) |

||

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Male, No. (%) | 326 (57) | 21 (60) | .66 |

| Age at inclusion, mean (SD), y | 31 (11) | 36 (11) | .01 |

| TOF with pulmonary atresia | 41 (7.1) | 3 (8.6) | .47 |

| QRS duration (n = 563), mean (SD), ms | 141 (27) | 152 (26) | .03 |

| QRS duration >180 ms | 26 (4.6) | 3 (8.6) | .27 |

| Surgical and clinical characteristics | |||

| Initial surgical correction with transannular patch | 283 (49) | 15 (43) | .59 |

| Age at surgical correction, median (IQR), y | 3.3 (1.4-6.7) | 5.7 (4.3-9.4) | .003 |

| Previous shunt procedure | 191 (33) | 19 (54) | .009 |

| Ventriculotomy incision | 273 (51) | 26 (74) | .05 |

| Previous supraventricular tachycardia | 59 (10) | 8 (23) | .006 |

| Previous ventricular tachycardia | 16 (2.8) | 4 (11) | .002 |

| Pulmonary valve replacement | |||

| Before CMR imaging | 167 (29) | 14 (40) | NA |

| After CMR imaging | 145 (25) | 13 (37) | NA |

| ICD implantation after CMR imaging | 24 (4.2) | 15 (43) | NA |

| CMR, mean (SD) | |||

| RV EF (n = 572), % | 44 (10) | 36 (13) | <.001 |

| LV EF (n = 567), % | 53 (8) | 47 (10) | <.001 |

| RV EDVI, mL/m2 (n = 572) | 126 (38) | 137 (40) | .11 |

| LV EDVI, mL/m2 (n = 567) | 88 (23) | 98 (37) | .007 |

| PR fraction, mean (SD), % | 26 (20) | 26 (23) | .78 |

Abbreviations: CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance; EDVI, end-diastolic volume index; EF, ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; IQR, interquartile range; LV, left ventricle; NA, not applicable; PR, pulmonary regurgitation; RV, right ventricle; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot.

Of 180 excluded patients, 41 (23%) had a pacemaker or an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implanted before inclusion in the registry. The other excluded patients did not undergo CMR examination for various other reasons such as claustrophobia or inability to comply with instructions.

Occurrence of Primary End Point

During a mean (SD) follow-up of 7.1 (3.5) years (median, 7.1 years; interquartile range, 4.7-9.8), 35 of 575 patients (6.1%) experienced the composite primary outcome of all-cause death (n = 13, 1 after ventricular arrhythmia), cardiac arrest/ventricular fibrillation (n = 8), sustained VT (n = 4), or recurrent symptomatic nonsustained VT (n = 11). One death (8%) was classified as sudden cardiac, 5 (38%) as heart failure, 1 (8%) as renal/cardiac failure, 1 (8%) as perioperative bleeding, and 5 (38%) as noncardiac or unknown. Baseline variables associated with the primary outcome are listed in Table 1.

Noninvasive Risk Stratification

The mean (SD) RV EF was 44% (10%) and mean (SD) LV EF was 53% (8%). There was a modest correlation between RV EF and LV EF (R, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.29-0.44; P < .001) (eFigure in the Supplement). Both variables were associated with the primary outcome in multivariable analysis (Table 2). The C statistic of the noninvasive components of the Khairy et al score was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.54-0.73) (Table 3). Right ventricular EF and LV EF had additional value when added as continuous variables to the model (2-category NRI, 0.15 and change C statistic, 0.09).

Table 2. Predictive Value in Univariable and Multivariable Analysisa.

| Predictor Variable | Univariable | Multivariable (n = 552) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Prior palliative shunt | 2.44 (1.26-4.75) | .009 | 1.77 (0.88-3.56) | .11 |

| QRS duration ≥180 ms | 1.94 (0.59-6.34) | .27 | 0.67 (0.15-3.10) | .61 |

| Ventriculotomy incision | 2.13 (0.99-4.56) | .05 | 1.67 (0.76-3.66) | .20 |

| Previous VT | 5.02 (1.77-14.2) | .002 | 3.98 (1.13-14.0) | .03 |

| LV EF (per %)b | 0.92 (0.89-0.95) | <.001 | 0.95 (0.92-0.99) | .01 |

| RV EF (per %)b | 0.94 (0.91-0.97) | <.001 | 0.96 (0.92-0.99) | .01 |

| LV EF <45%c | 4.77 (2.42-9.39) | <.001 | 3.23 (1.57-6.65) | .001 |

| RV EF <30%c | 5.28 (2.62-10.6) | <.001 | 3.90 (1.84-8.26) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: EF, ejection fraction; HR, hazard ratio; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Predictive value of the variables in the original Khairy et al risk model and the cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging thresholds, which were only included in the adapted model. Predictive value for adverse outcomes in univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis are described as HR with 95% CIs and P values.

Multivariable analysis was first performed with RV EF and LV EF as continuous variables.

The HRs reported for RV EF less than 30% and LV EF less than 45% were based on a multivariable model including the noninvasive component of the Khairy et al risk model but without RV EF and LV EF as continuous variables.

Table 3. Final Noninvasive Risk Model.

| Variable | Points |

|---|---|

| Prior palliative shunt | 2 |

| QRS duration ≥180 ms | 1 |

| Ventriculotomy incision | 2 |

| Previous VT | 2 |

| LV EF <45%a | 2 |

| RV EF <30%a | 3 |

| Total points | 0-12 |

Abbreviations: EF, ejection fraction; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Risk models were created by adding the total number of points per patient. The final adapted risk model, including biventricular function thresholds, is added in Table 3.

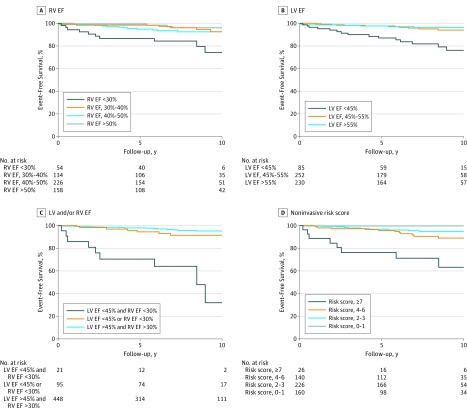

The primary outcome occurred in 12 of 54 patients (22%) with severe RV dysfunction (RV EF <30%) compared with only 2 of 50 patients (4%) with RV EF at 30% to 35% (eTable in the Supplement). Optimal thresholds determined in multivariable analysis were less than 30% for RV EF (hazard ratio, 3.90; 95% CI, 1.84-8.26; P < .001) and less than 45% for LV EF (hazard ratio, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.57-6.65; P = .001), corrected for noninvasive components of the Khairy et al risk model (Figure and Table 3). There was no interaction between previous pulmonary valve replacement and RV EF less than 30% or LV EF less than 45%, indicating thresholds are applicable in patients with and without pulmonary valve replacement.

Figure. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Left Ventricular (LV)/Right Ventricular (RV) Dysfunction Categories.

Kaplan-Meier curves for event-free survival in different RV (A) and LV (B) dysfunction categories. C, Event-free survival in patients with no biventricular dysfunction, RV or LV dysfunction, or biventricular dysfunction. D, Event-free survival according to the final noninvasive point-based risk model. EF indicates ejection fraction.

When compared with the model with RV EF and LV EF as continuous predictors, a model including RV EF less than 30% and LV EF less than 45% as dichotomized predictors only was noninferior (2-category NRI, 0.07; change C statistic, 0.03). The C statistic of the final noninvasive point-based risk model, including RV EF less than 30% and LV EF less than 45%, was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.63-0.85) (Table 3 and Figure, D). There was significant improvement compared with the noninvasive model without CMR (2-category NRI, 0.22; change C statistic, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.03-0.19; P = .009).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is among the largest to investigate CMR parameters as predictors of major outcomes in TOF and will further define its role in clinical decision-making. The newly quantified thresholds (RV EF <30% and LV EF <45%) for biventricular dysfunction were independently predictive and had additional value in risk stratification compared with the noninvasive components of the Khairy et al risk model.

Risk stratification may identify patients with increased risk for life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death who could benefit from ICD implantation. Our reported biventricular thresholds (RV EF <30% and LV EF <45%) were different compared with those reported in the study by Valente et al (RV EF <48% and LV EF <55%). These differences may be related to the specific analysis performed to determine optimal thresholds in our study and small differences in study design and CMR techniques. Furthermore, we found that combined biventricular dysfunction was clinically highly important, suggesting adverse effects of RV and LV dysfunction are cumulative.

A risk model proposed by Khairy et al is commonly used in patients with TOF, although 2 variables (inducible sustained VT and LV end-diastolic pressure ≥12 mm Hg) require invasive investigations, and no CMR variables were included in the original model. This risk model was constructed in a selected group of TOF ICD recipients, which may limit its use to identify patients for ICD implantation. In the present study, CMR imaging had additional value in noninvasive risk stratification, combined with noninvasive components proposed by Khairy et al. Not all variables were statistically significant in multivariable analysis, possibly owing to differences in design of both studies and limited statistical power. Importantly, diagnostic accuracy (C statistic, 0.75) of the final point-based model may be insufficient to directly identify patients for ICD implantation for primary prevention. Alternatively, the present noninvasive risk model could be used to select high-risk patients for invasive investigations to further asses the need for ICD implantation, although this needs to be determined in future studies. In addition, future studies may determine whether other CMR measurements, such as myocardial mass, diffuse myocardial fibrosis, or strain, have additional value in risk stratification.

Study Limitations

Although only patients from university centers were included in this study, almost all patients with TOF receive medical care in university centers in the Netherlands. Patients in the CONCOR registry without CMR imaging for various reasons were excluded. Furthermore, there was no central core laboratory and CMR was performed according to local protocols with variation in timing. This study lacked data on biventricular mass, exercise capacity, invasive risk factors (inducible sustained VT and LV end-diastolic pressure), and other hemodynamic anomalies (eg, tricuspid regurgitation). Last, future studies are needed to validate the thresholds and the adapted noninvasive risk model.

Conclusions

This large multicenter, prospective registry of patients with repaired TOF identified thresholds for ventricular dysfunction (RV EF <30% and LV EF <45%) to predict major adverse clinical outcomes. A combination of both thresholds with the noninvasive components proposed by Khairy et al may be used for noninvasive risk stratification.

eFigure. Correlation between LV EF and RV EF.

eTable. Prevalence and Event Rates for Biventricular Function Categories.

References

- 1.d’Udekem Y, Galati JC, Rolley GJ, et al. Low risk of pulmonary valve implantation after a policy of transatrial repair of tetralogy of Fallot delayed beyond the neonatal period: the Melbourne experience over 25 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(6):563-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gatzoulis MA, Balaji S, Webber SA, et al. Risk factors for arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death late after repair of tetralogy of Fallot: a multicentre study. Lancet. 2000;356(9234):975-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valente AM, Gauvreau K, Assenza GE, et al. Contemporary predictors of death and sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot enrolled in the INDICATOR cohort. Heart. 2014;100(3):247-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orwat S, Diller G-P, Kempny A, et al. ; German Competence Network for Congenital Heart Defects Investigators . Myocardial deformation parameters predict outcome in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot. Heart. 2016;102(3):209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, De Groot NM, et al. ; Task Force on the Management of Grown-up Congenital Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC); Association for European Paediatric Cardiology (AEPC); ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) . ESC guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). Eur Heart J. 2010;31(23):2915-2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bokma JP, Winter MM, Oosterhof T, et al. Preoperative thresholds for mid-to-late haemodynamic and clinical outcomes after pulmonary valve replacement in tetralogy of Fallot. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(10):829-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knauth AL, Gauvreau K, Powell AJ, et al. Ventricular size and function assessed by cardiac MRI predict major adverse clinical outcomes late after tetralogy of Fallot repair. Heart. 2008;94(2):211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khairy P, Harris L, Landzberg MJ, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in tetralogy of Fallot. Circulation. 2008;117(3):363-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khairy P, Van Hare GF, Balaji S, et al. PACES/HRS Expert Consensus Statement on the Recognition and Management of Arrhythmias in Adult Congenital Heart Disease: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS): endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), and the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ISACHD). Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(10):e102-e165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vriend JWJ, van der Velde ET, Mulder BJM. National registry and DNA-bank of patients with congenital heart disease: the CONCOR-project [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2004;148(33):1646-1647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oosterhof T, van Straten A, Vliegen HW, et al. Preoperative thresholds for pulmonary valve replacement in patients with corrected tetralogy of Fallot using cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2007;116(5):545-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uno H, Tian L, Cai T, Kohane IS, Wei LJ. A unified inference procedure for a class of measures to assess improvement in risk prediction systems with survival data. Stat Med. 2013;32(14):2430-2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapel GFL, Sacher F, Dekkers OM, et al. Arrhythmogenic anatomical isthmuses identified by electroanatomical mapping are the substrate for ventricular tachycardia in repaired tetralogy of Fallot [published online May 26, 2016]. Eur Heart J. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen C-A, Dusenbery SM, Valente AM, Powell AJ, Geva T. Myocardial ECV fraction assessed by CMR is associated with type of hemodynamic load and arrhythmia in repaired tetralogy of Fallot. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(1):1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wald RM, Haber I, Wald R, Valente AM, Powell AJ, Geva T. Effects of regional dysfunction and late gadolinium enhancement on global right ventricular function and exercise capacity in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot. Circulation. 2009;119(10):1370-1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Correlation between LV EF and RV EF.

eTable. Prevalence and Event Rates for Biventricular Function Categories.