Abstract

Importance

Studies comparing surgical results of rhinoplasty using autologous costal cartilage (ACC) and irradiated homologous costal cartilage (IHCC) are rare.

Objectives

To compare the clinical results of major augmentation rhinoplasty using ACC vs IHCC and analyze the histologic properties of both types of cartilage.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective clinical study was conducted among patients who had undergone rhinoseptoplasty using ACC or IHCC from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2014. Patients were followed up for more than 1 year after surgery and the histologic characteristics of ACC and IHCC were compared. The details of the surgical procedures and complications, including warping, infection, resorption, and/or donor-site morbidity, were evaluated by reviewing medical records and facial photographs. Patients’ subjective satisfaction with aesthetic and functional results was evaluated using a questionnaire.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The details of the surgical procedures and complications, including warping, infection, resorption, and/or donor-site morbidity; patients’ subjective satisfaction with aesthetic and functional results’ objective evaluation of surgical outcomes, including symmetry, dorsal height, dorsal length, dorsal width, tip projection, tip rotation, tip width, and overall result; and histologic structures. Objective evaluation of surgical outcomes was graded using the Objective Rhinoplasty Outcome Score, which assessed symmetry, dorsal height, dorsal length, dorsal width, tip projection, tip rotation, tip width, and overall result. Histologic structures were evaluated using hematoxylin and eosin, Masson trichrome, Alcian blue, and Verhoeff elastic stains.

Results

A total of 63 patients (27 males and 36 females; mean [SD] age, 30.6 [9.5] years) had rhinoseptoplasty using ACC and 20 (9 males and 11 females; mean [SD] age, 35.4 [15.4] years) had rhinoseptoplasty using IHCC. Among observed complications, only notable resorption occurred more frequently in patients using IHCC (6 [30%]) than with ACC (2 [3%]) (P = .002). In subjective evaluations of aesthetic satisfaction, patients who received ACC showed significantly greater satisfaction (37 of 51 patients [73%] were very satisfied) than did those who received IHCC (6 of 20 [30%]) (P = .001). However, there was no between-group difference in subjective functional outcomes: 4 of 51 patients receiving ACC (8%) and 5 of 20 receiving IHCC (25%) were satisfied (P = .50) and 45 of 51 receiving ACC (88%) and 15 of 20 receiving IHCC (75%) were very satisfied (P = .15). Regarding objective aesthetic outcomes, all scores for both ACC and IHCC were more than 3.1 (between good and excellent). Histologic analyses showed larger, more evenly distributed, uniform chondrocytes and more collagens and proteoglycan contents in ACC than in IHCC.

Conclusions and Relevance

Compared with patients receiving IHCC, those receiving ACC for rhinoseptoplasty showed superior aesthetic satisfaction; ACC also had less frequent notable resorption. Autologous costal cartilage also had better histologic properties than IHCC did, suggesting it as an ideal graft material with less chance of long-term resorption.

Level of Evidence

3.

This cohort study compares the results of major augmentation rhinoplasty using autologous costal cartilage vs irradiated homograft costal cartilage and analyzes the histologic properties of both types of cartilage.

Key Points

Questions

Does autologous costal cartilage or irradiated homograft costal cartilage have a better clinical outcome in augmentation rhinoplasty and what are the histologic properties relevant to the differences?

Findings

In this cohort study of 63 patients who received autologous costal cartilage and 20 patients who received irradiated homograft costal cartilage, notable resorption was less frequent with autologous costal cartilage, with higher subjective patient satisfaction compared with irradiated homograft costal cartilage, but the rates of warping were not different. Autologous costal cartilage showed better histologic properties than irradiated homograft costal cartilage.

Meaning

Autologous costal cartilage may be an ideal material with the least chance of long-term resorption for augmentation rhinoplasty.

Introduction

Autologous costal cartilage (ACC) is the graft material of choice for revision rhinoplasty, severe saddle nose deformity, or short contracted nose deformity, when large amounts of cartilage are needed. However, ACC has been criticized owing to its long operation time and high rate of donor-site morbidities, such as pneumothorax, postoperative pain, and scarring. Homologous cartilage, such as irradiated homologous costal cartilage (IHCC), has been used to overcome these disadvantages. Homologous cartilage offers easy availability, with no harvesting morbidity; however, the unpredictable rates of infection and resorption as well as the lack of long-term studies on these cartilages have been criticized.

Postoperative outcomes and complications associated with autologous and homologous costal cartilage have been reported. However, to our knowledge, studies comparing surgical results of rhinoplasty using these 2 graft materials are rare.

The purpose of this study was to present the clinical outcomes of major dorsal augmentation using ACC and IHCC and to compare the histologic properties of these materials. We intend to provide a reference for choosing the appropriate graft material for augmentation rhinoplasty.

Methods

Clinical Evaluations

The study included patients who underwent primary or revision rhinoplasty using ACC and/or IHCC at Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2014. Data from 63 patients (27 males and 36 females) who used ACC and 20 patients (9 males and 11 females) who used IHCC (CGBio Co, Ltd) were analyzed. All patients were followed up for more than 1 year. All operations were performed by one of us (H.-R.J.). Retrospective reviews of medical records, telephone interviews, and analyses of photographs were performed for analysis.

The study protocol was approved by the Boramae Medical Center Institutional Review Board, and the study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Autologous costal cartilage or IHCC was used primarily to augment volume deficiency of the dorsum and sometimes to restore integrity of the septum and tip. The ACC harvesting method was the same as that described previously. Rib cartilage (4-5 cm) was harvested from the right chest. Grafts were taken from the central portion by symmetrically carving out the periphery using a No. 10 blade. A boat-shaped graft was carved with slight concavity on the undersurface to match the contour of the nasal dorsum and to avoid any dead space. The cartilage was submerged in warm saline 2 or 3 times (for at least 10 minutes) between carvings to help minimize warping after the final carving. The cartilage was soaked in an antibiotic solution (clindamycin phosphate, 300 mg/mL) before implantation. In all patients, 1 large graft was inserted for dorsal augmentation. Dorsal grafts were 30 to 40 mm long, 4 to 6 mm thick, and 8 to 10 mm wide; the size varied according to the patient. When the dorsal augmentation was not sufficiently satisfactory or the graft did not fit, thin graft layers were stacked underneath the dorsal graft to achieve an acceptable dorsal height or complete fitting. The graft was sutured to the underlying framework to prevent slippage or movement.

Details of the surgical procedures and complications, including warping, infection, resorption, and/or donor-site morbidity, were thoroughly evaluated by reviewing medical records and comparing serial facial photographs. For consistency, standard preoperative and postoperative photographs had been taken of each patient using the same lighting, background, positioning, and photographic equipment. Whenever possible, subsequent postoperative photographs were taken semiannually.

Notable resorption was defined when the patient noticed and reported decreased nose height and the surgeon noticed significant graft resorption when comparing the photographs of the last follow-up with the previous photographs. Obvious warping was defined when the patient noticed and reported implant deviation and the surgeon graded implant deviation as more than 5° from the straight vertical axis of the dorsum at the last follow-up using Adobe Photoshop CS5 (Adobe) by measuring the angle between the straight vertical axis of the dorsum and the axis of the warped portion.

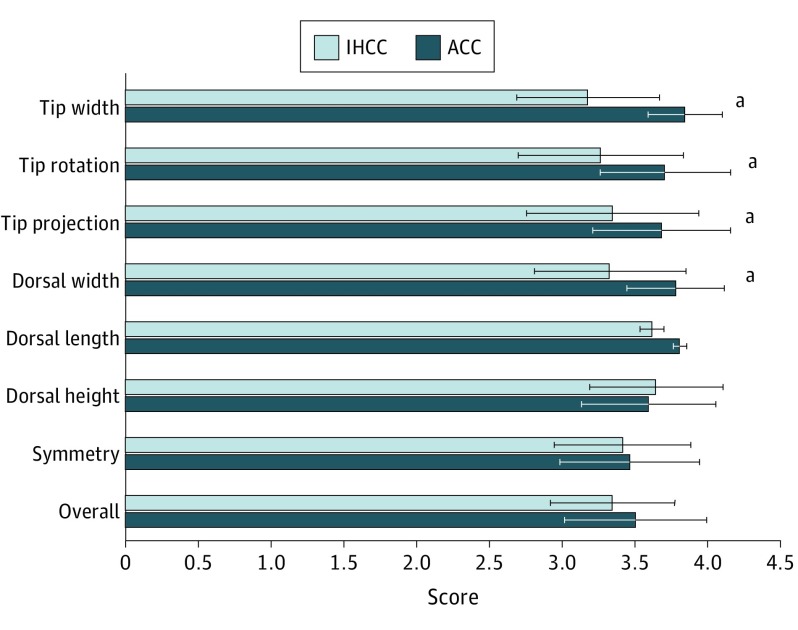

Patients’ subjective satisfaction for aesthetic and functional results was also evaluated in person at the outpatient clinic or by telephone survey, which used a simple questionnaire that included items on nasal function (smelling and nasal obstruction) and a graded self-evaluation of postoperative nasal appearance (0, dissatisfied; 1, no change; 2, satisfied; and 3, very satisfied). For objective evaluation of aesthetic results, 2 rhinoplasty surgeons (W.S.N. and H.K.) blinded to the study’s purpose compared standardized preoperative photographs with photographs taken at the last follow-up visit. The postoperative result was graded using the Objective Rhinoplasty Outcome Score, which is a modified version of the independent rhinoplasty outcome score suggested by Chin and Uppal. Eight components, including symmetry, dorsal height, dorsal length, dorsal width, tip projection, tip rotation, tip width, and overall result, were evaluated on a 5-point scale (0, poor; 1, no improvement; 2, moderate; 3, good; and 4, excellent). Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc). Fisher exact tests and χ2 tests were used to compare nominal variables.

Histologic Evaluations

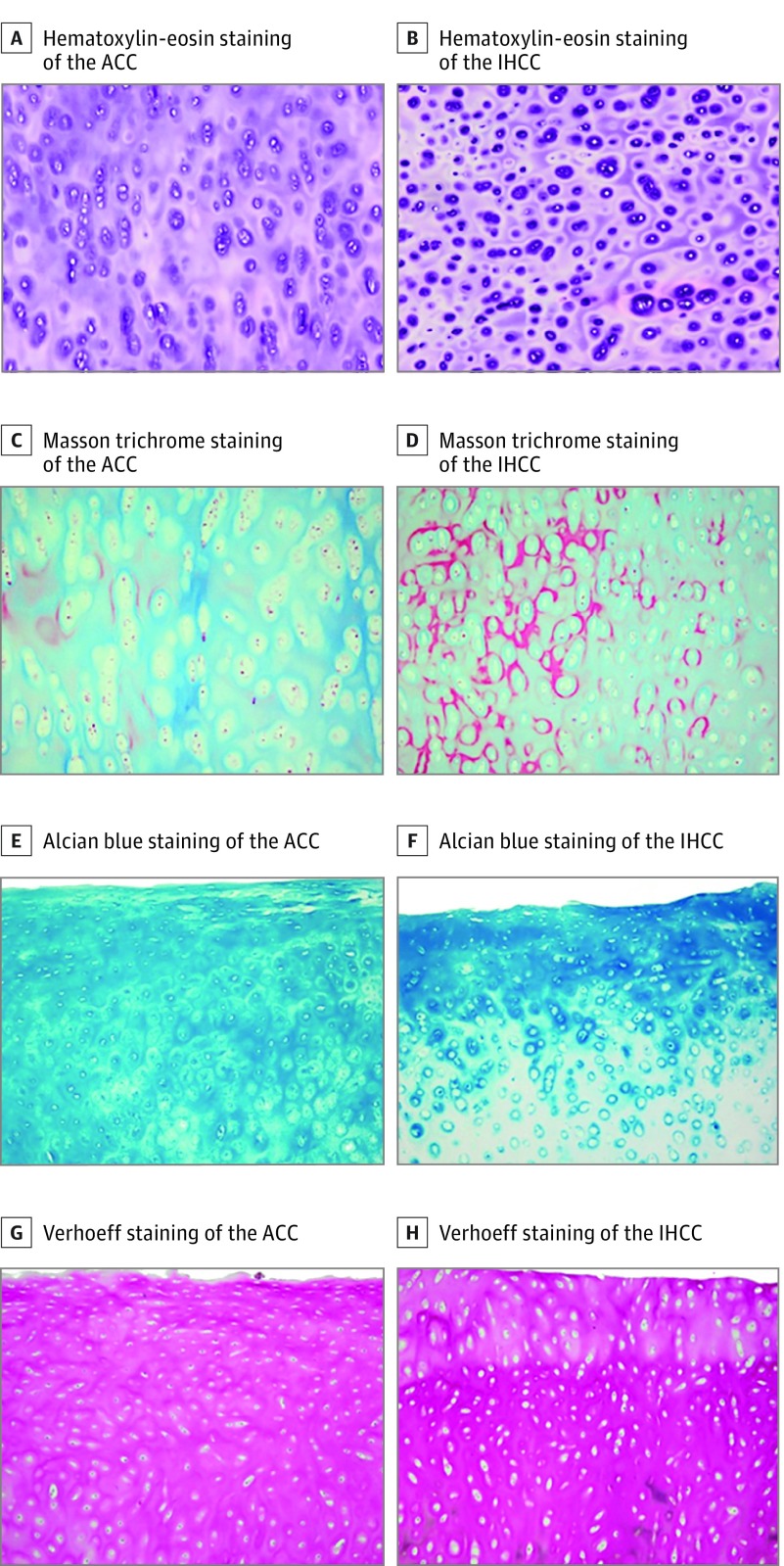

Four different samples each of ACC and IHCC were used for histologic analysis. All specimens were rehydrated, preserved, fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde, decalcified with sodium formate solution, dehydrated through a series of graded ethanols, and embedded in paraffin. The materials were sectioned at 5-μm thicknesses, deparaffinized, and stained according to the following methods. The size and number of chondrocytes and the levels of matrix production were assessed in sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Characteristic constituent molecules within the cartilage matrix were assessed with Masson trichrome staining for collagen content, Alcian blue staining for proteoglycans, and Verhoeff staining for elastic fibers.

Results

Clinical Outcomes

The mean postoperative follow-up period was 25.6 months (range, 12-71 months) for patients receiving ACC and 38.8 months (range, 22-53 months) for those receiving IHCC. The mean age was 30.6 years (range, 17-53 years) for patients receiving ACC and 35.4 years (range, 15-68 years) for those receiving IHCC. Among the 63 patients using ACC, 26 (41%) were undergoing revision and 2 (3%) had surgery performed with the endonasal approach. Among the 20 patients using IHCC, 10 (50%) were undergoing revision and 4 (20%) had surgery performed with the endonasal approach. In addition to the dorsum, ACC was used for tip grafts in 24 patients (38%), for the septum in 15 (24%), and for alar surgery in 5 (8%); IHCC was used for tip grafts in 15 patients (75%), for the septum in 14 (70%), and for alar surgery in 4 (20%).

Details of complications for each group are summarized in Table 1. The occurrence of obvious warping (ACC, 4 [6%] vs IHCC, 2 [10%]; P = .35), minimal warping (ACC, 4 [6%] vs IHCC, 0; P = .32), and infection (ACC, 3 [5%] vs IHCC, 1 [5%]; P = .68) was not different between groups. Notable resorption occurred more frequently in the IHCC group (6 [30%]) than in the ACC group (2 [3%]; P = .002).

Table 1. Complications Associated With Rhinoplasty Using ACC and IHCC.

| Complication | No. (%)a | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACC (n = 63) |

IHCC (n = 20) |

||

| Warping | 8 (13) | 2 (10) | .55 |

| Obvious warping | 4 (6) | 2 (10) | .35 |

| Minimal warping without disfigurement | 4 (6) | 0 | .32 |

| Infection | 3 (5) | 1 (5) | .68 |

| Notable resorption | 2 (3) | 6 (30) | .002 |

| Hypertrophic chest scar | 2 (3) | NA | NA |

| Pneumothorax | 2 (3) | NA | NA |

| Prolonged donor site pain | 0 | NA | NA |

| Total No. with complications | 17 (27) | 9 (45) | NA |

Abbreviations: ACC, autologous costal cartilage; IHCC, irradiated homologous costal cartilage; NA, not applicable.

The complications are not mutually exclusive.

Fisher exact test.

Of 63 patients using ACC, 12 were excluded owing to failure to participate in a telephone follow-up survey or absence of long-term postoperative photographs. Therefore, 51 patients (22 men and 29 women) using ACC and all 20 patients using IHCC were chosen for subjective and objective aesthetic analyses.

Subjective evaluations of satisfaction with aesthetic and functional outcomes are shown in Table 2. In terms of subjective aesthetic evaluation, among the ACC group, 37 patients (73%) were very satisfied, 4 (8%) were satisfied, 5 (10%) found no change, and 5 (10%) were dissatisfied. Among the IHCC group, 6 patients (30%) were very satisfied, 9 (45%) were satisfied, 3 (15%) found no change, and 2 (10%) were dissatisfied. With respect to aesthetic evaluation, significantly more patients using ACC were very satisfied than those using IHCC (P = .001). However, there was no significant between-group difference in functional outcome assessments: 4 of 51 patients receiving ACC (8%) and 5 of 20 receiving IHCC (25%) were satisfied (P = .50) and 45 of 51 receiving ACC (88%) and 15 of 20 receiving IHCC (75%) were very satisfied (P = .15). The primary reasons for subjective dissatisfaction were obvious warping, nostril asymmetry, low tip projection, or notable dorsal resorption. Objective evaluations for aesthetic outcomes are shown in Figure 1. For both groups, scores for the 8 factors were more than 3.1 (between good and excellent). There was no significant difference between groups in scores for symmetry (ACC, 3.47 vs IHCC, 3.42; P = .72), dorsal height (ACC, 3.60 vs IHCC, 3.65; P = .67), dorsal length (ACC, 3.81 vs IHCC, 3.62; P = .05), or overall results (ACC, 3.51 vs IHCC, 3.35; P = .19). Those in the ACC group showed significantly better scores than did those in the IHCC group for dorsal width (3.78 vs 3.33; P = .001), tip projection (3.69 vs 3.35; P = .03), tip rotation (3.71 vs 3.27; P = .005), and tip width (3.85 vs 3.18; P < .001).

Table 2. Subjective Satisfaction With the Aesthetic and Functional Outcomes of Rhinoplasty With ACC and IHCC.

| Subjective Satisfaction | No. (%) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACC (n = 51) |

IHCC (n = 20) |

||

| Aesthetic | |||

| Dissatisfied | 5 (10) | 2 (10) | .64 |

| No change | 5 (10) | 3 (15) | .40 |

| Satisfied | 4 (8) | 9 (45) | .001 |

| Very satisfied | 37 (73) | 6 (30) | .001 |

| Functional | |||

| Dissatisfied | 2 (4) | 0 | .51 |

| No change | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Satisfied | 4 (8) | 5 (25) | .50 |

| Very satisfied | 45 (88) | 15 (75) | .15 |

Abbreviations: ACC, autologous costal cartilage; IHCC, irradiated homologous costal cartilage; NA, not applicable.

Fisher exact test.

Figure 1. Objective Aesthetic Evaluation With the Objective Rhinoplasty Outcome Score.

Each factor is scored on a 5-point scale (0, poor; 1, no improvement; 2, moderate; 3, good; and 4, excellent). Horizontal bars indicate SD.

aP < .05.

Histologic Findings

Chondrocytes in IHCC were smaller, less uniform, more unevenly distributed, and had fewer nucleated lacunae than those in ACC (Figure 2A and B). In sections stained with Masson trichrome and Alcian blue, collagen and proteoglycan were less dense in IHCC than in ACC (Figure 2C through F). However, Verhoeff staining, which is directed at elastic fibers, did not show a significant difference between the 2 types of cartilage (Figure 2G and H).

Figure 2. Histologic Findings.

A, Hematoxylin-eosin staining (original magnification ×100) of the autologous costal cartilage (ACC). B, Hematoxylin-eosin staining (original magnification ×100) of the irradiated homologous costal cartilage (IHCC). C, Masson trichrome staining (original magnification ×100) of the ACC. D, Masson trichrome staining (original magnification ×100) of the IHCC. The chondroid matrix, which was stained blue, indicates the presence of abundant collagen. E, Alcian blue staining (original magnification ×100) of the ACC. F, Alcian blue staining (original magnification ×100) of the IHCC. The prominent blue staining documents the presence of sulfated glysosaminoglycans. G, Verhoeff staining (original magnification ×100) of the ACC. H, Verhoeff staining (original magnification ×100) of the IHCC. The elastic fibers are stained bluish black in the lacunar territorial matrix.

Discussion

We compared surgical outcomes of rhinoplasty using ACC and IHCC and investigated the different clinical outcomes with respect to histologic characteristics. The most notable difference was a much higher resorption rate with IHCC (30%) than with ACC (3%) and subsequent lower aesthetic satisfaction among patients receiving IHCC.

The higher resorption of IHCC, especially when used as a major dorsal augmentation material, is thought to be inevitable considering the preparation process. Because the cartilage is exposed to 30 to 40 kGy of gamma radiation using a cobalt 60 source to remove all donor cells and using major histocompatibility antigens to limit the graft-vs-host response, chondrocyte viability in IHCC is low and increased resorption over time is inevitable. A study on the effects of ionizing radiation on costal cartilage also showed that radiation decreases the collagen fiber content of cartilage. Our histologic study of IHCC indicated these effects of radiation, showing less nucleated lacunae and fewer and less dense collagen fibers and proteoglycans. Our results showed some nucleated lacunae in IHCC although, theoretically, there should be no viable chondrocytes after radiation. However, the viability of chondrocytes could not be determined because these findings may arise from the limitation of light microscopy, in that it is not sensitive enough to assess the viability of cartilage grafts. In a study evaluating the viability of homograft cartilage, on light microscopy the chondrocytes were not histologically dissimilar from viable chondrocytes; however, electron microscopy revealed severe cell degeneration.

In addition to the inherent histologic inferiority of IHCC, the fact that 50% of patients receiving IHCC were undergoing revision may have played a role in the higher rate of resorption observed in this group, because the poor blood supply in the recipient bed of those undergoing revision would decrease graft viability even more with IHCC than with ACC. The fact that 4 of 6 patients showing notable resorption had undergone revision supports this idea.

This study also showed considerable individual variation in the amount of resorption in the group using IHCC. This variation can be attributed to a few factors. First, the quality of the costal cartilage obtained from cadavers is not always the same between donors. Second, the status of the recipient bed of the graft may differ between individuals. Slight resorption of a dorsal graft may be easily perceived, both by the patient and surgeon, when the dorsum is augmented considerably by a single piece of graft.

Although there are many reports on the use of IHCC in rhinoplasty, the resorption rates are controversial and long-term follow-up studies are rare. The largest study on IHCC reported a resorption rate of 1.4% after a mean follow-up of 13 years in 357 patients. The number of patients enrolled was larger and the length of the follow-up period in that study was longer than in other studies. However, the exact number of patients who experienced resorption was underestimated, because the rate of resorption was not calculated according to the number of patients but according to the number of IHCC grafts implanted. This calculation has some limitations because the graft on the septum cannot be evaluated correctly and the exact location of resorption is not clear when there are multiple implants. The actual number of patients with resorption was 10 of 357 patients, resulting in an increase in the resorption rate to 2.8%. The authors also reported that IHCC grafts were quite stable and maintained structural contours. In contrast, in another study, 18 of 24 grafts (75%) in patients who were followed up for 11 to 16 years were completely resorbed.

Several studies have reported a rate of warping with IHCC from none to 14.7%. Our results showed that warping rates were not different between the ACC (8 [13%]) and IHCC (2 [10%]) groups. Warping is associated with the internal stress system within the costal cartilage itself and the interplay of cortical and core portions and to the method and technique of the surgeon carving the cartilage. Here, the core portion of the rib cartilage was used for all major dorsal augmentation, and the carving was performed by 1 surgeon (H.-R.J.); thus, there was likely no surgeon or technique bias.

Objective aesthetic outcomes were better in the ACC group for the factors evaluating the tip, although most scores for factors evaluating the dorsum were not different between groups. It is difficult to explain clearly why the tip parameters were better in the ACC group. When IHCC is used, it is difficult to carve a thin, flat piece of cartilage to be used for tip modification owing to quality problems. It is less pliable and requires thicker pieces than does ACC; because many Asian patients need a septal extension graft to modify the tip shape, carving out a thin piece of cartilage for this purpose is more difficult with IHCC than with ACC. Furthermore, the higher rate of resorption of IHCC may have influenced the final shape of the tip in this group.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, ACC harvested from the patients and IHCC supplied by the company were not age-matched. The ages of the cadavers that IHCC was prepared from were not specified. Because composition of costal cartilage changes with age and affects histologic results, an accurate age-matched comparison was impossible. Second, this clinical study had a relatively small sample size and short follow-up. Further studies in a larger number of patients with longer follow-up periods could show more clinically significant results. Third, we used subjective methods to measure graft resorption. Further studies that include intraoperative measurement of graft volume and serial follow-up measurements of volume or an anthropometric study will improve the scientific validity of the study.

Conclusions

In the clinical evaluation of ACC and IHCC for major dorsal augmentation, notable resorption was lower and subjective satisfaction higher with ACC than with IHCC, but warping rates were not different. Autologous costal cartilage also showed better histologic characteristics, suggesting that it is an ideal graft material with less chance of long-term resorption.

References

- 1.Cakmak O, Ergin T. The versatile autogenous costal cartilage graft in septorhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2002;4(3):172-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park JH, Jin HR. Use of autologous costal cartilage in Asian rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(6):1338-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dingman RO, Grabb WC. Costal cartilage homografts preserved by irradiation. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1961;28:562-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strauch B, Wallach SG. Reconstruction with irradiated homograft costal cartilage. Plast Reconst Surg. 2003;111(7):2405-2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welling DB, Maves MD, Schuller DE, Bardach J. Irradiated homologous cartilage grafts: long-term results. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114(3):291-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wee JH, Park MH, Oh S, Jin HR. Complications associated with autologous rib cartilage use in rhinoplasty: a meta-analysis. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;17(1):49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varadharajan K, Sethukumar P, Anwar M, Patel K. Complications associated with the use of autologous costal cartilage in rhinoplasty: a systematic review. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35(6):644-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kridel RW, Ashoori F, Liu ES, Hart CG. Long-term use and follow-up of irradiated homologous costal cartilage grafts in the nose. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11(6):378-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams WP Jr., Rohrich RJ, Hollier LH, Minoli J, Thornton LK, Gyimesi I. Anatomic basis and clinical implications for nasal tip support in open versus closed rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(1):255-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefkovits G. Irradiated homologous costal cartilage for augmentation rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;25(4):317-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin KY, Uppal R. Improved access in endonasal rhinoplasty: the cross cartilaginous approach. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(6):781-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hizal E, Buyuklu F, Ozer O, Cakmak O. Effects of different levels of crushing on the viability of rabbit costal and nasal septal cartilages. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(5):1045-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke AJ, Wang TD, Cook TA. Irradiated homograft rib cartilage in facial reconstruction. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6(5):334-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoksted P, Ladefoged C. Crushed cartilage in nasal reconstruction. J Laryngol Otol. 1986;100(8):897-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinho AC Jr, Rosifini Alves-Claro AP, Pino ES, et al. Effects of ionizing radiation and preservation on biomechanical properties of human costal cartilage. Cell Tissue Bank. 2013;14(1):117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman CK, Strauch B. Dorsal augmentation rhinoplasty with irradiated homograft costal cartilage. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22(2):120-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami CS, Cook TA, Guida RA. Nasal reconstruction with articulated irradiated rib cartilage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117(3):327-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toriumi DM. Surgical correction of the aging nose. Facial Plast Surg. 1996;12(2):205-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]