Key Points

Question

Do changes in diabetic retinopathy severity occur while patients are receiving the anti-vascular endothelial growth factors aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema?

Findings

In a preplanned secondary analysis of randomized clinical trial data, among eyes with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, the aflibercept and ranibizumab groups had significantly higher improvement rates at 1 year, but no apparent treatment differences were identified at 2 years. For eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy, 1-year and 2-year improvement rates were significantly higher in the aflibercept group; moreover, over 2 years, no treatment differences in the rates of diabetic retinopathy worsening were observed among all eyes.

Meaning

Eyes receiving anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for diabetic macular edema may experience retinopathy improvement; rates of diabetic retinopathy worsening were low.

Abstract

Importance

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy for diabetic macular edema (DME) favorably affects diabetic retinopathy (DR) improvement and worsening. It is unknown whether these effects differ across anti-VEGF agents.

Objective

To compare changes in DR severity during aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab treatment for DME.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Preplanned secondary analysis of data from a comparative effectiveness trial for center-involved DME was conducted in 650 participants receiving aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab. Retinopathy improvement and worsening were determined during 2 years of treatment. Participants were randomized in 2012 through 2013, and the trial concluded on September 23, 2015.

Interventions

Random assignment to aflibercept, 2.0 mg; bevacizumab, 1.25 mg; ranibizumab, 0.3 mg, up to every 4 weeks through 2 years following a retreatment protocol.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Percentages with retinopathy improvement at 1 and 2 years and cumulative probabilities for retinopathy worsening through 2-year without adjustment for multiple outcomes.

Results

A total of 650 participants (495 [76.2%] nonproliferative DR [NPDR], 155 proliferative DR [PDR]) were analyzed; 302 (46.5%) were women and mean (SD) age was 61 (10) years; 425 (65.4%) were white. At 1 year, among 423 NPDR eyes, 44 of 141 (31.2%) treated with aflibercept, 29 of 131 (22.1%) with bevacizumab, and 57 of 151 (37.7%) with ranibizumab had improvement of DR severity (adjusted difference: 11.7%; 95% CI, 2.9% to 20.6%; P = .004 for aflibercept vs bevacizumab; 8.9%; 95% CI, 1.7% to 16.1%; P = .01 for ranibizumab vs bevacizumab; and 2.9%; 95% CI, −5.7% to 11.4%; P = .51 for aflibercept vs ranibizumab). At 2 years, 33 eyes (24.8%) in the aflibercept group, 25 eyes (22.1%) in the bevacizumab group, and 40 eyes (31.0%) in the ranibizumab group had DR improvement; no treatment group differences were identified. For 93 eyes with PDR at baseline, 1-year improvement rates were 75.9% for aflibercept, 31.4% for bevacizumab, and 55.2% for ranibizumab (adjusted difference: 50.4%; 95% CI, 26.8% to 74.0%; P < .001 for aflibercept vs bevacizumab; 20.4%; 95% CI, −3.1% to 44.0%; P = .09 for ranibizumab vs bevacizumab; and 30.0%; 95% CI, 4.4% to 55.6%; P = .02 for aflibercept vs ranibizumab). These rates and treatment group differences appeared to be maintained at 2 years. Despite the reduced numbers of injections in the second year, 66 (59.5%) of NPDR and 28 (70.0%) of PDR eyes that manifested improvement at 1 year maintained improvement at 2 years. Two-year cumulative rates for retinopathy worsening ranged from 7.1% to 10.2% and 17.2% to 26.4% among anti-VEGF groups for NPDR and PDR eyes, respectively. No statistically significant treatment differences were noted.

Conclusions and Relevance

At 1 and 2 years, eyes with NPDR receiving anti-VEGF treatment for DME may experience improvement in DR severity. Less improvement was demonstrated with bevacizumab at 1 year than with aflibercept or ranibizumab. Aflibercept was associated with more improvement at 1 and 2 years in the smaller subgroup of participants with PDR at baseline. All 3 anti-VEGF treatments were associated with low rates of DR worsening. These data provide additional outcomes that might be considered when choosing an anti-VEGF agent to treat DME.

This cohort study compares changes in diabetic retinopathy severity after participants have received 1 and 2 years of treatment with aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab.

Introduction

Treatment of vision impairment from center-involved diabetic macular edema (DME) has evolved from focal/grid photocoagulation to intravitreous anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy. Clinical trials have demonstrated superior visual acuity (VA) and anatomic outcomes for periods of 2 or 5 years in eyes with DME when aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab was compared with laser treatment. The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) compared these anti-VEGF agents for DME (Protocol T); results demonstrated that 1- and 2-year vision outcomes were similar among the 3 anti-VEGF groups for eyes with entry VA of 20/32 to 20/40. For eyes with baseline VA of 20/50 to 20/320, aflibercept had superior VA outcomes compared with bevacizumab at and over (area under the curve) 2 years. Aflibercept had superior VA outcomes compared with ranibizumab at 1 year, which were no longer present at 2 years, although the area under the curve over 2 years was superior with aflibercept in this subgroup.

Several clinical trials have shown that eyes randomly assigned to aflibercept or ranibizumab to manage DME are less likely to experience diabetic retinopathy (DR) worsening and more likely to have DR improvement compared with focal/grid photocoagulation or observation alone; similar trends on the effects of bevacizumab have been suggested. However, to our knowledge, no data exist comparing the relative effect of these agents on the evolution of DR severity within a randomized clinical trial. This analysis explored those comparisons for DR improvement or worsening through 2 years in a preplanned secondary analysis using data from the DRCR.net Protocol T.

Methods

Study procedures have been reported previously and are summarized briefly herein (protocol available at http://www.drcr.net). Principal eligibility criteria included a single study eye with center-involved DME confirmed by optical coherence tomography and best-corrected electronic VA letter score of 78 through 24 (approximate Snellen equivalent, 20/32 through 20/320). Eyes were not eligible if they had received anti-VEGF treatment within 12 months of enrollment. A total of 660 eyes were randomized 1:1:1 to intravitreous injections of aflibercept, 2.0 mg; bevacizumab, 1.25 mg; or ranibizumab, 0.3 mg. All participants had visits every 4 weeks through week 52. Most eyes were required to receive injections every 4 weeks through week 20. Starting at the 24-week visit, injections were withheld if there was no improvement or worsening in VA and central subfield thickness from the previous 2 consecutive injections, even if the central subfield was 250 μm or more (Stratus equivalent). After week 52, follow-up could be extended to 8-week and then 16-week intervals if injections were deferred at 2 consecutive visits. Injections were resumed if either VA or central subfield thickness worsened by 5 or more letters or 10%, respectively, compared with the last visit or injection. Focal/grid laser was performed starting at week 24 or thereafter if persistent DME was not improving and there were macular areas amenable to photocoagulation. Participants provided written informed consent, and each participant received a $25 gift card at each study visit. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki; a listing of the institutional review boards that approved the study is given in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Standard 7-field or 4-field-wide digital color fundus photographs were obtained at baseline as well as the 1-year and 2-year visits. Retinopathy severity was evaluated by masked graders at the Fundus Photography Reading Center (76.9% on 7-field and 23.1% on 4-field wide). Changes in DR severity were evaluated in 2 distinct subgroups based on baseline fundus photographs: nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study [ETDRS] retinopathy levels 10-53) vs proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) (ETDRS levels 60-85). Ten participants were excluded due to ungradable or unavailable baseline photographs.

Definitions for retinopathy improvement or worsening are summarized in Table 1. Diabetic retinopathy–worsening events (ie, panretinal photocoagulation, vitrectomy, or anti-VEGF injection [to manage PDR or its complications], vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, anterior segment neovascularization, or neovascular glaucoma) were collected prospectively. Data from participants who did not have photographs available at the 1- or 2-year visit were excluded from improvement analyses (61 eyes at 1 year; 118 eyes at 2 years).

Table 1. Definitions for DR Improvement or Worsening at Follow-up.

| Criteria | Definition |

|---|---|

| Improvement in DR Was Achieved if Both of the Following Criteria Were Met During Follow-up | |

| Documentation on case report forma | (1) NPDR and PDR: no PRP or vitrectomy or anti-VEGF injection (to manage PDR or its complications) was performed, and no vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment (traction, rhegmatogenous, combined, or unspecified), anterior segment neovascularization or neovascular glaucoma was identified |

| Assessment of annual fundus photographs by reading center | (2A) NPDR and PDR: improvement by 2 or more levels on the ETDRS DR scale vs baseline or (2B) PDR: regression of active PDR (level ≥61) to no PDR (level ≤53 if no prior PRP, or to level 60 if PRP was present at entry) |

| Baseline DR severity ineligible for improvement | Inactive PDR: (level 60) (2B) PDR: microaneurysms only or less (level 10, 12, 14, 15, or 20) |

| Worsening of DR Included Any of the Following Events During Follow-up | |

| Documentation on case report form | (1) PRP or vitrectomy or anti-VEGF injection (to manage PDR or its complications), (2) vitreous hemorrhage, (3) retinal detachment, or (4) neovascularization of the iris or angle or neovascular glaucoma |

| Assessment of annual fundus photographs by reading centerb | (6) Worsening by ≥2 levels on the ETDRS severity scale vs baseline, (7A) worsening from no PDR to PDR (level ≤53 progresses to level 60 or higher), (7B) progression from ≤ high risk PDR to advanced PDR (level 60-75 progresses to level 81-85) |

| Baseline DR severity ineligible for worsening | Advanced PDR (level 81 or 85) |

Abbreviations: DR, diabetic retinopathy; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; NPDR, nonproliferative DR; PDR, proliferative DR; PRP, panretinal photocoagulation; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Eyes that manifested worsening of DR with any PDR-related event were considered as nonimprovers in the improvement analysis.

Cases with missing photographic data because of nonperformance of photographs or nongradable photographs at a completed visit were considered as no event for the photograph component in the composite worsening outcome at that annual time point.

Statistical Analysis

The cross-sectional percentages (95% CIs; obtained using Clopper-Pearson exact method) of eyes with DR improvement by treatment group were reported at each annual visit and were compared using binomial regression with adjustment for baseline DR severity category. Longitudinal cumulative probabilities of DR worsening (95% CI) through 2 years were calculated using the life-table method. Participants who did not meet the definition of worsening were censored following their last visit. Diabetic retinopathy worsening was compared between treatment groups using a Cox proportional hazards regression model with adjustment for baseline DR severity category. To adjust for potential confounding, separate sensitivity analysis of treatment group comparison was performed that included adjustment for both baseline DR severity and imbalanced baseline characteristics for both improvement and worsening outcomes.

All P values and 95% CIs are 2-sided. The overall type 1 error rate was controlled at 5% using the Hochberg method for multiple treatment group comparisons. No adjustment for analysis of multiple outcomes was performed. SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), was used for statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 650 participants were analyzed. Of these participants, 302 (46.5%) were women, mean (SD) age was 61 (10) years, and 425 (65.4%) participants were white. Nonproliferative DR was present in 495 (76.2%) of the 650 study eyes among participants who had evaluable baseline photographs. Eighteen eyes (3.6%) with a DR severity level of 20 or better were excluded from the improvement analyses since they did not meet the criteria of eyes that were eligible for improvement. The remaining 155 participants (23.8%) had PDR at baseline (66 [42.6%] women; age, 57 [10] years; 95 [61.3%] white). Fifty-five eyes (35.5%) with a DR severity level of 60 (panretinal photocoagulation without neovascularization) were excluded from the improvement analysis because they did not meet the criteria of eyes that were eligible for improvement. Percentages with gradable photographs at the 1- and 2-year visits appeared to be similar among the treatment groups with 1 exception: slightly fewer ranibizumab eyes had 1- or 2-year photographs among the PDR eyes (43 [87.8%] and 38 [79.2%], respectively) compared with aflibercept (44 [95.7%] and 41 [89.1%]) and bevacizumab (54 [91.5%] and 49 [86.0%]) (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Baseline characteristics of individuals included in this analysis are reported by treatment group and baseline DR subgroup in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Individuals who completed the annual visits appeared to be similar between anti-VEGF groups with a few exceptions. The ranibizumab group had the highest rates of prior panretinal photocoagulation and more severe DR. Among participants with baseline NPDR, the bevacizumab group was slightly older and the aflibercept group had more participants with type 1 diabetes. Among participants with baseline PDR, the bevacizumab group had a slightly longer duration of either type of diabetes and the aflibercept group had thicker average baseline central subfield thickness (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

DR Improvement

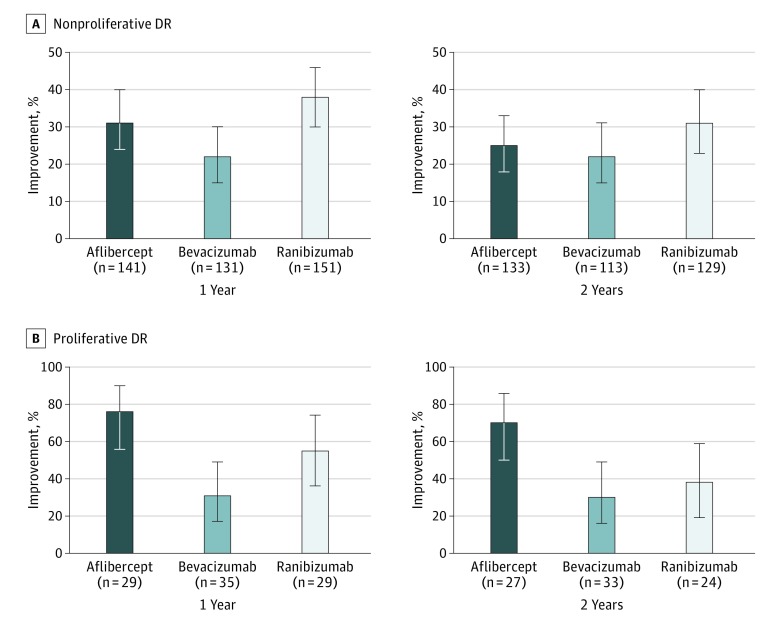

Among the eyes with NPDR at baseline, 423 (88.7%) were evaluable for DR improvement at the 1-year visit and 375 (78.6%) were evaluable for DR improvement at the 2-year visit. At the 1-year visit (Table 2, Figure 1A), 44 eyes (31.2%) in the aflibercept group, 29 eyes (22.1%) in the bevacizumab group, and 57 eyes (37.7%) in the ranibizumab group had DR improvement (adjusted difference for aflibercept-bevacizumab, 11.7%; 95% CI, 2.9% to 20.6%; P = .004; adjusted difference for ranibizumab vs bevacizumab, 8.9%; 95% CI, 1.7% to 16.1%; P = .01; and adjusted difference for aflibercept-ranibizumab, 2.9%; 95% CI, −5.7% to 11.4%; P = .51). At the 2-year visit, 33 eyes (24.8%) in the aflibercept group, 25 eyes (22.1%) in the bevacizumab group, and 40 eyes (31.0%) in the ranibizumab group had DR improvement; no treatment group differences were identified. A post hoc subgroup analysis of NPDR eyes with more severe levels of NPDR (levels 47 and 53) at baseline showed higher rates of improvement, varying from 51.9% to 64.6% at 1 year (n = 188), which were fairly stable at 2 years (n = 169), without any treatment group differences at either time point (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Among the 111 participants with level 35 through 53 DR at baseline who improved at 1 year and had gradable photographs at the 1- and 2-year visits, 66 (59.5%) eyes maintained DR improvement at the 2-year visit (sustained improvement), including 20 (50.0%) among the aflibercept group, 16 (72.7%) among the bevacizumab group, and 30 (61.2%) among the ranibizumab group (P = .74). Only 30 eyes among the 253 (11.9%) eyes with gradable photographs at the 1- and 2-year visits that had not improved at 1 year improved at the 2-year visit (11 [12.8%] eyes in the aflibercept group, 9 [10.2%] in the bevacizumab group, and 10 [12.7%] in the ranibizumab group).

Table 2. DR Improvement: Percentage With Improvement at Annual Visits by Anti-VEGF Treatment Group and Baseline DR Statusa.

| Characteristic | Aflibercept | Bevacizumab | Ranibizumab | Pairwise Treatment Group Comparisons (Adjusted 95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aflibercept vs Bevacizumab | Aflibercept vs Ranibizumab | Ranibizumab vs Bevacizumab | ||||

| With NPDR at Baseline | ||||||

| Eyes, No.c | 167 | 147 | 163 | |||

| Improvement at 1 y | ||||||

| Eyes improved/eyes with gradable photographs, No.d | 44/141 | 29/131 | 57/151 | |||

| Improvement, % (95% CI) | 31.2 (23.7 to 39.5) | 22.1 (15.4 to 30.2) | 37.7 (30.0 to 46.0) | 11.7 (2.9 to 20.6) | 2.9 (−5.7 to 11.4) | 8.9 (1.7 to 16.1) |

| Adjusted P value | .004 | .51 | .01 | |||

| Improvement at 2 y | ||||||

| Eyes improved/eyes with gradable photographs, Nod | 33/133 | 25/113 | 40/129 | |||

| Improvement, % (95% CI) | 24.8 (17.7 to 33.0) | 22.1 (14.9 to 30.9) | 31.0 (23.2 to 39.7) | 3.1 (−3.3 to 9.5) | 0.7 (−6.4 to 7.7) | 2.4 (−4.0 to 8.7) |

| Adjusted P value | .85 | .85 | .85 | |||

| With PDR at Baseline | ||||||

| Eyes, No.c | 30 | 38 | 32 | |||

| Improvement at 1 y | ||||||

| Eyes improved/eyes with gradable photographs, No.d | 22/29 | 11/35 | 16/29 | |||

| Improvement, % (95% CI) | 75.9 (56.5 to 89.7) | 31.4 (16.9 to 49.3) | 55.2 (35.7 to 73.6) | 50.4 (26.8 to 74.0) | 30.0 (4.4 to 55.6) | 20.4 (−3.1 to 44.0) |

| Adjusted P value | <.001 | .02 | .09 | |||

| Improvement at 2 y | ||||||

| Eyes improved/eyes with gradable photographs, No.d | 19/27 | 10/33 | 9/24 | |||

| Improvement, % (95% CI) | 70.4 (49.8 to 86.2) | 30.3 (15.6 to 48.7) | 37.5 (18.8 to 59.4) | 35.9 (6.1 to 65.6) | 31.4 (−0.6 to 63.4) | 4.5 (−20.5 to 29.4) |

| Adjusted P value | .01 | .06 | .73 | |||

Abbreviations: DR, diabetic retinopathy; NPDR, nonproliferative DR; PDR, proliferative DR.

Empty cells indicate not applicable.

Difference in percentage with improvement. Pairwise comparisons of retinopathy improvement were performed using binomial regression with adjustment for categorical baseline DR severity and multiple treatment group comparisons. NPDR eyes were categorized into 2 subgroups: (1) mild or moderate NPDR (level 35 or 43), or (2) moderately severe or very severe NPDR (level 47 or 53). PDR eyes were categorized into 3 subgroups: (1) mild (level 61), (2) moderate (level 65), or (3) high-risk (level 71 or 75). Reported P values and 95% CIs were adjusted using the Hochberg method to account for an overall type 1 error of .05.

Including only eyes that were evaluable for improvement at baseline (ie, excluding eyes with baseline DR severity level of ≤20, or level 60).

Eyes that were evaluable for improvement at baseline and had gradable photographs at the corresponding annual visit were included in the analysis. 95% CIs for the binomial proportions of improvement were obtained using Clopper-Pearson exact method.

Figure 1. Percentage With Improvement of Retinopathy at 1 and 2 Years by Baseline Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) Status .

A, Nonproliferative DR at baseline. The respective levels of significance for the pairwise comparisons at the 1-year and 2-year visits were aflibercept vs bevacizumab, P = .004 and P = .85; aflibercept vs ranibizumab, P = .51 and P = .85; and ranibizumab vs bevacizumab, P = .01 and P = .85. B, Proliferative DR at baseline. The respective levels of significance for the pairwise comparisons at the 1-year and 2-year visits were aflibercept vs bevacizumab, P < .001 and P = .01; aflibercept vs ranibizumab, P = .02 and P = .06; and ranibizumab vs bevacizumab, P = .09 and P = .73. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Improvement of DR among the 100 eyes with PDR level 61 or greater at baseline could be assessed in 93 eyes (93.0%) at the 1-year visit and 84 eyes (84.0%) at the 2-year visit. One-year improvement rates (Table 2, Figure 1B) were 22 (75.9%) in the aflibercept group, 11 (31.4%) in the bevacizumab group, and 16 (55.2%) in the ranibizumab group (adjusted difference for aflibercept-bevacizumab, 50.4%; 95% CI, 26.8% to 74.0%; P < .001; adjusted difference for ranibizumab-bevacizumab, 20.4%; 95% CI, −3.1% to 44.0%; P = .09; and adjusted difference for aflibercept-ranibizumab, 30.0%; 95% CI, 4.4% to 55.6%; P = .02). Rates for DR improvement within groups from the 1- to 2-year visits as well as treatment group differences between the anti-VEGF agents largely were maintained at the 2-year visit (Table 2). Among the 40 participants with PDR at baseline and gradable photographs at both the 1- and 2-year visits, 28 (70.0%) eyes had sustained improvement of DR, including 14 (70.0%) among the aflibercept group, 7 (77.8%) among the bevacizumab group, and 7 (63.6%) among the ranibizumab group (P = .77). Among the 42 eyes that did not improve by the 1-year visit, 9 eyes (21.4%), including 4 of 6 (66.7%) aflibercept, 3 of 23 (13.0%) bevacizumab, and 2 of 13 (15.4%) ranibizumab eyes, improved by the 2-year visit.

Sensitivity analyses, including comparisons of 2-year DR improvement rates, using last observation carried forward for participants with only 1-year photographs (eTable 3 in the Supplement), and comparisons of 2-step or more photographic improvement rates only among participants with gradable photographs (eTable 4 in the Supplement) were consistent in magnitude and direction with the findings reported for the NPDR and PDR subgroups. The comparisons between treatment groups adjusting for baseline imbalanced factors also yielded similar conclusions. The overall rates of DR improvement combining NPDR and PDR groups are provided in eTable 5 in the Supplement.

DR Worsening

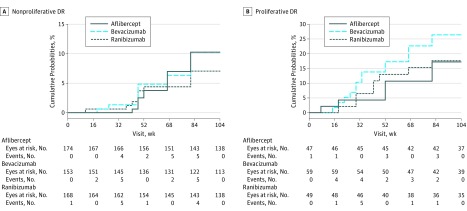

Figure 2A provides the cumulative probabilities of DR worsening by treatment group among eyes with NPDR at baseline. At the 1-year visit, rates of worsening were less than 5% in all groups. Worsening rates slowly continued to increase, but no treatment group differences were observed at the 2-year visit (Table 3), with rates of worsening at 10.2% for the aflibercept group, 10.2% for the bevacizumab group, and 7.1% for the ranibizumab group (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] for aflibercept vs bevacizumab, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.49-2.06; P = .99; adjusted HR for ranibizumab vs bevacizumab, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.26-1.59; P = .54; and adjusted HR for aflibercept vs ranibizumab, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.65-3.79; P = .54). A post hoc subgroup analysis of the 218 eyes with moderate-severe or severe NPDR (level 47 or 53) at baseline resulted in 2-year cumulative rates of worsening of 18.3% (11 eyes) in aflibercept eyes, 12.9% (7 eyes) in bevacizumab eyes, and 6.5% (5 eyes) in ranibizumab eyes (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). eTable 6 in the Supplement reports the distribution of the specific events that initially triggered categorization as worsening of DR. Among eyes with NPDR at baseline, vitreous hemorrhage was the initial worsening event in the majority (9 [56.3%]) of the 16 aflibercept eyes, while a 2-step progression of DR severity shown on photographs accounted for 5 (35.7%) and 6 (54.5%) of the worsening events for the 14 bevacizumab and 11 ranibizumab eyes, respectively. However, 6 of the 17 eyes that worsened by the 1-year visit (2 in each anti-VEGF arm) and 16 of the 41 eyes that worsened by the 2-year visit (6 eyes in the aflibercept group, 6 eyes in the bevacizumab group, and 4 eyes in the ranibizumab group) met more than 1 criterion of DR worsening. Four (<1%) eyes developed neovascularization on photographs at 1 year and 12 (2.4%) eyes developed neovascularization on photographs at 2 years.

Figure 2. Cumulative Probability of Worsening of Retinopathy During Follow-up of 2 Years by Baseline Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) Status .

A, Nonproliferative DR at baseline. The respective levels of significance for the pairwise comparisons through the 2-year visit were aflibercept vs bevacizumab, P = .99; aflibercept vs ranibizumab, P = .54; and ranibizumab vs bevacizumab, P = .54. B, Proliferative DR at baseline. The respective levels of significance for the pairwise comparisons through the 2-year visit were aflibercept vs bevacizumab, P = .70; aflibercept vs ranibizumab, P = .70; and ranibizumab vs bevacizumab, P = .62.

Table 3. DR Worsening: Cumulative Probabilities for Worsening Through 1 and 2 Yearsa.

| Characteristic | Aflibercept | Bevacizumab | Ranibizumab | Pairwise Treatment Group Comparisons: HR of Worsening (Adjusted 95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aflibercept vs Bevacizumab | Aflibercept vs Ranibizumab | Ranibizumab vs Bevacizumab | ||||

| With NPDR at Baselinec | ||||||

| No. of eyes | 174 | 153 | 168 | |||

| Worsening by 1 yd | ||||||

| No. of eyes worsened | 4 | 7 | 6 | |||

| Cumulative probability of worsening, % (95% CI) | 2.5 (0.9-6.5) | 4.8 (2.3-9.9) | 3.7 (1.7-8.1) | |||

| Worsening by 2 y | ||||||

| No. of eyes worsened | 16 | 14 | 11 | |||

| Cumulative probability of worsening, % (95% CI) | 10.2 (6.4-16.2) | 10.2 (6.2-16.7) | 7.1 (4.0-12.4) | 1.00 (0.49-2.06) | 1.57 (0.65-3.79) | 0.64 (0.26-1.59) |

| Adjusted P value | .99 | .54 | .54 | |||

| With PDR at Baselineb | ||||||

| No. of eyes | 47 | 59 | 49 | |||

| Worsening by 1 yd | ||||||

| No. of eyes worsened | 2 | 8 | 6 | |||

| Cumulative probability of worsening, % (95% CI) | 4.3 (1.1-16.0) | 13.8 (7.1-25.7) | 13.0 (6.0-26.6) | |||

| Worsening by 2 y | ||||||

| No. of eyes worsened | 8 | 15 | 8 | |||

| Cumulative probability of worsening, % (95% CI) | 17.2 (9.0-31.4) | 26.4 (16.8-39.9) | 17.6 (9.2-32.2) | 0.70 (0.29-1.69) | 1.22 (0.44-3.42) | 0.57 (0.20-1.65) |

| Adjusted P value | .70 | .70 | .62 | |||

Abbreviations: DR, diabetic retinopathy; HR, hazard ratio; NPDR, nonproliferative DR; PDR, proliferative DR; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Empty cells indicate not applicable.

Pairwise comparisons of retinopathy worsening were performed using a Cox proportional hazards regression model with adjustment for baseline DR multiple treatment group comparisons. NPDR eyes were stratified into 2 subgroups: (1) moderate NPDR or better (level ≤43), or (2) moderately severe or very severe NPDR (level 47 or 53). PDR eyes were stratified into 4 subgroups: (1) inactive (level 60), (2) mild (level 61), (3) moderate (level 65), or (4) high-risk (level 71 or 75). Reported P values and 95% CIs were adjusted using the Hochberg method to account for an overall type 1 error of .05.

Cumulative probabilities of retinopathy worsening were obtained from life-table estimates.

Under the Cox proportional hazards regression model assumption, the HR for worsening from each pairwise comparison was considered constant at any time point throughout 2 years of follow-up. The proportional hazards assumption was examined by including interaction terms with time in the model, which were not statistically significant (ie, P > .05). The global hazards of worsening were similar at 1 and 2 years in both the NPDR group (P = .15) and PDR group (P = .78).

Figure 2B shows the cumulative probability of DR worsening by treatment group among eyes with PDR at baseline. Rates of worsening were higher for eyes with PDR than NPDR. The cumulative probability of worsening by the 2-year visit was 17.2% for the aflibercept group, 26.4% for the bevacizumab group, and 17.6% for the ranibizumab group. No statistically significant differences between treatment groups (Table 3) were identified (adjusted HR for aflibercept vs bevacizumab, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.29-1.69; P = .70; adjusted HR for ranibizumab vs bevacizumab, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.20-1.65; P = .62; and adjusted HR for aflibercept vs ranibizumab, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.44-3.42; P = .70). Vitreous hemorrhage was the initial event indicating DR worsening in most eyes, irrespective of drug assignment (eTable 6 in the Supplement), although during follow-up, 12 of the 31 eyes that worsened by the 2-year visit had more than 1 type of event consistent with DR worsening (including 2 eyes among the aflibercept group, 7 eyes among the bevacizumab group, and 3 eyes among the ranibizumab group).

Sensitivity analyses restricting the NPDR and PDR analysis cohorts to participants who had gradable photographs at the 1- and 2-year visits (eTable 3 in the Supplement) and restricting the worsening criteria to photographic documentation of 2-step or more worsening (eTable 7 in the Supplement) showed similar results. No significant differences in conclusions from the secondary analyses, including additional adjustment for baseline risk factors, were identified. eTable 5 in the Supplement presents the overall cumulative probabilities of DR worsening combining NPDR and PDR groups.

Post Hoc Analysis of Number of Intravitreous Injections and Improvement in DR Severity

The average number of injections from baseline to the 1- and 2-year visits is given in eTable 8 in the Supplement by DR improvement and baseline DR subgroup. At the 1-year visit in both the aflibercept and ranibizumab groups, eyes with NPDR that received more injections were more likely to demonstrate DR improvement (mean injection number for improvers vs nonimprovers was 10.1 vs 8.4 for aflibercept [P < .001] and 10.2 vs 8.9 for ranibizumab [P = .009]). At the 2-year visit, the cumulative mean injection number for improvers vs nonimprovers was 14.3 vs 12.9 for aflibercept, 17.2 vs 14.4 for bevacizumab, and 17.3 vs 13.4 for ranibizumab. There was an association between the total mean number of injections and DR improvement (P < .001 combining all treatment groups), which was similar across treatment groups. Among the more limited number of eyes that had PDR, no significant associations between the total number of injections and DR improvement were identified at the 1- and 2-year visits.

Discussion

Findings from this preplanned secondary analysis of changes in DR are consistent with previous studies that have identified improvement in DR and low rates of DR worsening in eyes actively managed with repeated intravitreous injections of anti-VEGF agents for DME, even in the absence of monthly fixed dosing. The present study expands on those findings suggesting that improvement rates can differ among aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab when following our treatment protocol.

In this trial, most patients (76.2%) had NPDR. Although an improvement of 2 or more levels on the ETDRS retinopathy scale occurred with each anti-VEGF agent, treatment with aflibercept or ranibizumab was more likely to be associated with improvement at 1 year compared with bevacizumab among eyes with NPDR (Figure 1A, Table 2). At the 2-year visit, no differences in DR improvement rates were identified in eyes with NPDR between the 3 anti-VEGF agents. In the limited number of eyes with PDR at baseline, improvement was more common with aflibercept compared with either bevacizumab or ranibizumab at each of the 2 annual visits (Figure 1B, Table 2).

The greater improvement rates associated with aflibercept compared with the other anti-VEGF agents among the small group of eyes with PDR at baseline is consistent with other observations within this trial, specifically, the interaction between VA outcomes and baseline VA or central subfield thickness on optical coherence tomography. Among eyes with more severe disease (ie, worse VA, thicker central subfield thickness, or PDR at baseline), aflibercept had more favorable VA and anatomic outcomes, particularly at 1 year. Despite a reduced number of injections, on average, in the second year of treatment, approximately two-thirds of all eyes that manifested improvement at 1 year continued to manifest improvement at the 2-year visit, irrespective of baseline DR status or treatment group. An association between a greater number of intravitreous injections and improvement was identified among the eyes with NPDR, but the number and frequency of injections that may promote, optimize, and sustain this outcome cannot be ascertained from this trial. Most importantly, whether anatomic improvement in DR status has clinical relevance for outcomes that subsequently affect visual function remains unknown. This possibility is being explored in a DRCR.net trial evaluating the prevention of PDR or DME with vision loss comparing aflibercept with sham injections in eyes with moderately severe to severe NPDR and no DME at baseline.

The rates of DR worsening were relatively small across all 3 agents, with no significant differences identified. Nevertheless, some patients receiving anti-VEGF therapy for DME experience worsening of DR, warranting regular surveillance for worsening DR.

Limitations and Strengths

Limitations of this analysis include the finite follow-up period of 2 years, higher-than-ideal numbers of missed visits, and annual visits without gradable photographs. Fewer ranibizumab eyes had 1- or 2-year photographs among the eyes with PDR compared with aflibercept and bevacizumab. The number of patients with PDR and the severity of their disease was limited, and DR severity at baseline was not a stratification factor for randomization. In addition, there were treatment group imbalances in potentially important baseline factors, including baseline DR. However, all statistical analyses adjusted for baseline DR and sensitivity analyses that were adjusted for other potential confounding factors produced similar results. Composite definitions for worsening or improvement did not include investigator determination of DR severity level or data from fluorescein angiography, including ultrawide field images. Some strengths of this analysis include prospective, standardized data collection after the secondary analysis was planned, defined treatment regimens for administration of the anti-VEGF drugs, relatively large numbers of participants, random anti-VEGF assignment, masked grading of photographs, and inclusion of PDR worsening events that are not always readily apparent on fundus images in the composite outcome.

Conclusions

At 1 and 2 years, eyes with NPDR receiving anti-VEGF treatment for DME may experience improvement in DR severity. Less improvement was demonstrated with bevacizumab at 1 year than with aflibercept or ranibizumab. In the smaller subgroup of eyes with PDR at baseline, more improvement with aflibercept was identified at 1 and 2 years. All 3 anti-VEGF treatments were associated with low rates of DR worsening. These data provide additional outcomes that might be considered when choosing an anti-VEGF agent to treat DME.

eTable 1. Visit Completion and Availability of Gradable Photographs for Study Eyes by Baseline Retinopathy Status (Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy or Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy) and Drug Assignment

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics for Eyes Within Each Treatment Group That Completed the 1-Year and 2-Year Visit by Baseline Retinopathy Subgroup

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analysis of Retinopathy Improvement or Worsening at 2 Years by Anti-VEGF Treatment Group and Baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Status

eTable 4. Diabetic Retinopathy Improvement: Percentage With 2 or More Steps Improvement on Photos at Annual Visits by Anti-VEGF Treatment Group and Baseline Retinopathy Status

eTable 5. Diabetic Retinopathy Improvement or Worsening by Anti-VEGF Treatment Group Combining NPDR and PDR Subgroups

eTable 6. Distribution of the First Event Which Triggered Categorization as Worsening of Diabetic Retinopathy by Baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Status

eTable 7. Diabetic Retinopathy Worsening: Percentage With 2 or More Steps Worsening on Photos at Annual Visits by Anti-VEGF Treatment Group and Retinopathy Status

eTable 8. Number of Anti-VEGF Injections Administered to Manage Center-Involved DME by Baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Status and Diabetic Retinopathy Improvement Outcome

eFigure 1. Percentage With Improvement of Retinopathy Among Eyes With Moderately Severe or Severe Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy at Baseline

eFigure 2. Cumulative Probability of Retinopathy Worsening Among Eyes With Moderately Severe or Severe Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy at Baseline

References

- 1.Stone TW. ASRS 2015 Preferences and Trends Membership Survey. Chicago, IL: American Society of Retina Specialists; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korobelnik JF, Do DV, Schmidt-Erfurth U, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2247-2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1064-1077.e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Googe J, Brucker AJ, Bressler NM, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Randomized trial evaluating short-term effects of intravitreal ranibizumab or triamcinolone acetonide on macular edema after focal/grid laser for diabetic macular edema in eyes also receiving panretinal photocoagulation. Retina. 2011;31(6):1009-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen QD, Brown DM, Marcus DM, et al. ; RISE and RIDE Research Group . Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(4):789-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajendram R, Fraser-Bell S, Kaines A, et al. A 2-year prospective randomized controlled trial of intravitreal bevacizumab or laser therapy (BOLT) in the management of diabetic macular edema: 24-month data: report 3. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(8):972-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown DM, Nguyen QD, Marcus DM, et al. ; RIDE and RISE Research Group . Long-term outcomes of ranibizumab therapy for diabetic macular edema: the 36-month results from two phase III trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):2013-2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt-Erfurth U, Lang GE, Holz FG, et al. ; RESTORE Extension Study Group . Three-year outcomes of individualized ranibizumab treatment in patients with diabetic macular edema: the RESTORE extension study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1045-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown DM, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Do DV, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 100-week results from the VISTA and VIVID studies. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(10):2044-2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bressler SB, Glassman AR, Almukhtar T, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Five-year outcomes of ranibizumab with prompt or deferred laser versus laser or triamcinolone plus deferred ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;164:57-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elman MJ, Bressler NM, Qin H, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Expanded 2-year follow-up of ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(4):609-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Aflibercept, Bevacizumab, or Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema: Two-Year Results from a Comparative Effectiveness Randomized Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1351-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jampol LM, Glassman AR, Bressler NM, Wells JA, Ayala AR; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor comparative effectiveness trial for diabetic macular edema: additional efficacy post hoc analyses of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bressler SB, Qin H, Melia M, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Exploratory analysis of the effect of intravitreal ranibizumab or triamcinolone on worsening of diabetic retinopathy in a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(8):1033-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ip MS, Domalpally A, Hopkins JJ, Wong P, Ehrlich JS. Long-term effects of ranibizumab on diabetic retinopathy severity and progression. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(9):1145-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.clinicaltrials.gov. Comparative Effectiveness Study of Intravitreal Aflibercept, Bevacizumab, and Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema. NCT01627249. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01627249. Accessed March 16, 2017.

- 18.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group Fundus photographic risk factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy: ETDRS report number 12. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5)(suppl):823-833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75(4):800-802. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell P, Bandello F, Schmidt-Erfurth U, et al. ; RESTORE Study Group . The RESTORE study: ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(4):615-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.clinicaltrials.gov. Anti-VEGF Treatment for Prevention of PDR/DME. NCT02634333. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02634333. Accessed March 17, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Visit Completion and Availability of Gradable Photographs for Study Eyes by Baseline Retinopathy Status (Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy or Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy) and Drug Assignment

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics for Eyes Within Each Treatment Group That Completed the 1-Year and 2-Year Visit by Baseline Retinopathy Subgroup

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analysis of Retinopathy Improvement or Worsening at 2 Years by Anti-VEGF Treatment Group and Baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Status

eTable 4. Diabetic Retinopathy Improvement: Percentage With 2 or More Steps Improvement on Photos at Annual Visits by Anti-VEGF Treatment Group and Baseline Retinopathy Status

eTable 5. Diabetic Retinopathy Improvement or Worsening by Anti-VEGF Treatment Group Combining NPDR and PDR Subgroups

eTable 6. Distribution of the First Event Which Triggered Categorization as Worsening of Diabetic Retinopathy by Baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Status

eTable 7. Diabetic Retinopathy Worsening: Percentage With 2 or More Steps Worsening on Photos at Annual Visits by Anti-VEGF Treatment Group and Retinopathy Status

eTable 8. Number of Anti-VEGF Injections Administered to Manage Center-Involved DME by Baseline Diabetic Retinopathy Status and Diabetic Retinopathy Improvement Outcome

eFigure 1. Percentage With Improvement of Retinopathy Among Eyes With Moderately Severe or Severe Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy at Baseline

eFigure 2. Cumulative Probability of Retinopathy Worsening Among Eyes With Moderately Severe or Severe Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy at Baseline