Key Points

Question

What is the influence of lay navigation on cost and resource use of older adults with cancer?

Findings

In this observational study, we used regression analysis to compare changes in quarterly Medicare costs and health care use between patients navigated in the Patient Care Connect Program and a propensity score–matched group of nonnavigated patients. Compared with matched nonnavigated patients, outcomes declined more per quarter for navigated patients, including costs by $781.29, emergency department visits by 6.0%, hospitalizations by 7.9%, and intensive care unit admissions by 10.6%.

Meaning

Lay navigation programs should expand as health systems transition to value-based health care.

Abstract

Importance

Lay navigators in the Patient Care Connect Program support patients with cancer from diagnosis through survivorship to end of life. They empower patients to engage in their health care and navigate them through the increasingly complex health care system. Navigation programs can improve access to care, enhance coordination of care, and overcome barriers to timely, high-quality health care. However, few data exist regarding the financial implications of implementing a lay navigation program.

Objective

To examine the influence of lay navigation on health care spending and resource use among geriatric patients with cancer within The University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System Cancer Community Network.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This observational study from January 1, 2012, through December 31, 2015, used propensity score–matched regression analysis to compare quarterly changes in the mean total Medicare costs and resource use between navigated patients and nonnavigated, matched comparison patients. The setting was The University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System Cancer Community Network, which includes 2 academic and 10 community cancer centers across Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Participants were Medicare beneficiaries with cancer who received care at participating institutions from 2012 through 2015.

Exposures

The primary exposure was contact with a patient navigator. Navigated patients were matched to nonnavigated patients on age, race, sex, cancer acuity (high vs low), comorbidity score, and preenrollment characteristics (costs, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and chemotherapy in the preenrollment quarter).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Total costs to Medicare, components of cost, and resource use (emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit admissions).

Results

In total, 12 428 patients (mean (SD) age at cancer diagnosis, 75 (7) years; 52.0% female) were propensity score matched, including 6214 patients in the navigated group and 6214 patients in the matched nonnavigated comparison group. Compared with the matched comparison group, the mean total costs declined by $781.29 more per quarter per navigated patient (β = −781.29, SE = 45.77, P < .001), for an estimated $19 million decline per year across the network. Inpatient and outpatient costs had the largest between-group quarterly declines, at $294 and $275, respectively, per patient. Emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit admissions decreased by 6.0%, 7.9%, and 10.6%, respectively, per quarter in navigated patients compared with matched comparison patients (P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Costs to Medicare and health care use from 2012 through 2015 declined significantly for navigated patients compared with matched comparison patients. Lay navigation programs should be expanded as health systems transition to value-based health care.

This study examines the influence of lay navigation on health care spending and resource use among geriatric patients with cancer within an academic health system cancer community network.

Introduction

Despite spending more per patient than any other country, the quality of US health care remains suboptimal. This paradox has led to growing emphasis on the need for value-based health care, which is characterized by the “Triple Aim” of improved patient experience of care, better health of the population, and reduced per capita cost of health care. In cancer care delivery, costs are expected by 2020 to rise to $173 billion per year, in part because of the aging population and high expense associated with caring for geriatric patients. Innovative solutions are needed to transform the health care system.

The fragmented nature of US health care delivery and the lack of care coordination between care settings are barriers to high-quality, efficient care. Since the initial reports of lay navigation by Freeman, patient navigation programs have been used to improve access to cancer care, coordinate care delivery, and address barriers to achieving timely, high-quality health care. Navigation programs are expanding nationally and are being included as part of the Commission on Cancer accreditation, yet the optimal target population and strategy for delivering navigation services are not defined. Historically, most navigation programs focused on early detection and the initial management of cancer. Few data exist on navigation for patients with cancer throughout the cancer care continuum (initial, survivorship, and end of life). Evidence for the influence of navigation across this continuum is needed, including for patients at end of life, who are likely to have high symptom burden, experience hospitalizations, and incur higher medical costs. Providing navigation for patients with cancer across the continuum will require workforce expansion. Although nurses are the primary staff for many navigation programs, lay (nonclinical) navigation programs are becoming increasingly prevalent as a low-cost strategy to meet the demand for navigation service in the United States.

As part of a Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation award, we developed and implemented a lay navigation model, the Patient Care Connect Program (PCCP), for older Medicare beneficiaries with cancer across The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Health System Cancer Community Network (CCN). The goal of the program was to meet the Triple Aim of improved health care, better health, and lower costs by integrating lay navigators into the care team. The PCCP navigators aim to proactively identify patient needs, connect patients with resources, coordinate care, and empower patients to take a more active role in their health care. The introduction of lay navigation within the CCN also served as a practice transformation. Navigators, health care personnel, and administrators were engaged in discussions about health care delivery through analysis of shared data. We hypothesized that the PCCP navigation would result in lower health care costs and decreased use of costly medical care, such as emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions. In this analysis, we evaluated the influence of the PCCP by examining trends in these outcomes for navigated patients compared with a matched group of patients who did not receive navigation services.

Methods

Study Design and Oversight

We conducted a secondary analysis of Medicare administrative claims data from January 1, 2012, through December 31, 2015, for all older adults with cancer who received care within the CCN. Our objective was to compare costs and health care use for those receiving the PCCP lay navigation services and a matched cohort of patients who did not. The following institutional review boards at the UAB and each of the participating CCN sites approved the evaluation of the PCCP: Fort Walton Beach Medical Center, Fort Walton Beach, Florida; Gulf Coast Regional Medical Center, Panama City, Florida; Marshall Medical Center, Albertville, Alabama; Mitchell Cancer Institute, Mobile, Alabama; Memorial Hospital, Chattanooga, Tennessee; Northeast Alabama Regional Medical Center, Anniston; Northside Hospital Cancer Institute, Atlanta, Georgia; Russell Medical Center, Alexander City, Alabama; Southeast Alabama Medical Center, Dothan; Singing River Health System, Pascagoula, Mississippi; and the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center. Navigation is considered a standard of care within the PCCP, and no patient informed consent was necessary to enroll patients in the PCCP. A waiver of consent was granted by the UAB institutional review board to conduct this secondary analysis.

Study Population

The source population included Medicare beneficiaries 65 years or older with primary Medicare Part A and B insurance coverage and a cancer diagnosed from 2012 through 2015 within the CCN. Patients with health maintenance organization coverage were excluded. The CCN includes 2 academic and 10 community cancer centers of varying size and practice structure located in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Implementation of the PCCP began in March 2013 at the UAB site, and all sites were navigating patients by October 2013. Within the PCCP, patients were identified through a combination of ED or hospital census report review, clinician referral, and self-referral. The nurse site manager or head navigator would review these lists and assign patients to navigators to initiate contact. Priority was given to high-risk patients, including those with metastatic cancer, high-morbidity cancers (eg, pancreatic, ovarian, and lung), high-risk comorbidities (eg, diabetes, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), or history of ED visit or hospitalization in the prior month.

For this analysis, we defined 2 groups for comparison, the navigated group and a nonnavigated, matched comparison group. The navigated group included patients assigned to a navigator between March 2013 and June 2015. The matched comparison group was selected from nonnavigated patients diagnosed between January 2012 and June 2015. We assigned a pseudo-enrollment date to patients in the comparison group based on the frequency distributions of time from diagnosis to enrollment observed for the PCCP group. We restricted the analysis population to patients who had at least 1 quarter of observation before and 2 quarters of observation after the enrollment or pseudo-enrollment date. We further restricted the comparison group to patients who had a pseudo-enrollment date before death and before June 2015.

PCCP Navigation

Details of the PCCP, including patient selection, navigator training, and interventions, have been previously described. Briefly, lay navigators were hired from within the community and were required to have a bachelor’s degree but were not licensed clinicians, such as nurses or social workers. The mean navigator caseload was 152 patients per quarter. Navigator activities were guided by distress screenings that assessed practical, informational, financial, familial, emotional, spiritual, and physical concerns. Assistance on any distress item reported was provided at the patient’s request. Algorithms based on cancer type, cancer stage, comorbidities, type of care received, and distress levels guided the frequency of further contact. In addition, high levels of distress (≥4 on the distress thermometer) triggered a higher level of intervention by the nurse site manager or the health care professional. Navigators also encouraged patients to telephone them or the clinic before going to the ED.

Data Source

Data on cancer type, stage, and date of diagnosis were received from the local cancer registries of the 12 CCN sites. Medicare Part A and B claims data from inpatient, outpatient, physician visits (carrier), home health, durable medical equipment, skilled nursing facility, and hospice claims from 2012 through 2015 were extracted from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Chronic Condition Data Warehouse. Medicare Part D data were not available for this study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was Medicare costs per beneficiary per quarter (ie, amounts paid by Medicare for all care received, excluding Part D prescription drugs). Secondary outcomes included (1) source of cost (inpatient, outpatient, physician visits [carrier], home health, durable medical equipment, skilled nursing facility, and hospice claims) and (2) health care resource use, as defined by the number of ED visits, hospitalizations, or ICU admissions in each quarter. Health Care Financing Administration Common Procedural Coding System codes used to identify outcomes are listed in the eTable in the Supplement.

Matching

We matched groups using propensity scores with the following covariates: age at diagnosis, race, sex, cancer acuity (high vs low), phase of care, comorbidity score, baseline cost of care, baseline treatment with chemotherapy, and baseline ED and ICU use. Race was obtained from claims data and categorized as white, black, or other. Cancer acuity was categorized as high (brain, pancreatic, ovarian, lung, and head and neck or any stage IV cancer) or not. Cancer stage was defined using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results staging. Comorbid conditions were abstracted from claims data from 2012 through 2015 and classified using a weighted score of 0, 1, 2 to 3, or 4 or higher based on the Klabunde modification for comorbidities. We defined the following 3 distinct phases of care at time of enrollment or pseudo-enrollment: initial, survivorship, and end of life. The end-of-life phase was defined as the last 6 months of life. The initial phase included patients within 1 year of diagnosis who were not within the last 6 months of life. The survivorship phase spanned the period between the initial and end-of-life phases. Baseline costs, receipt of chemotherapy, and resource use were calculated for the quarter before enrollment or pseudo-enrollment to account for patients with inherent high use from unmeasured factors.

Once the matched comparison group was identified, we assessed the suitability of the match by examining the overlap of the propensity scores to verify the common support and covariate balance and by using 2-sample t tests and χ2 tests to evaluate the between-group differences in estimates and proportions. The procedure was repeated varying the covariates used until we obtained overlapping propensity scores with similar proportions of covariates.

Return on Investment

Salaries, including administrative support for the PCCP navigators, ranged from $33 400 to $42 300 per year, and the mean navigator caseload was 152 patients per quarter. For the return on investment, the mean annual salary of $37 850 with 28.0% for fringe benefits, for a total of $48 448, was considered the investment. The return was calculated based on a mean caseload per quarter of 152 patients per navigator multiplied by the difference in the mean decline in Medicare costs of navigated patients compared with nonnavigated patients.

Statistical Analysis

We described characteristics for all beneficiaries in the source population, the navigated group, and the matched nonnavigated comparison group. We used repeated-measures generalized linear models to evaluate trends in total cost based on the following covariates: group assignment (group), quarters after enrollment (time), calendar time, and the interaction between group and time. The primary coefficient of interest was the group × time interaction. Furthermore, we examined the differences in the mean quarterly reductions for each type of cost in the following separate generalized linear models: inpatient, outpatient, physician visits (carrier), home health, skilled nursing facility, and hospice. Generalized linear models with the Poisson distribution and log link function with the same set of covariates were used to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for ED visits, hospitalizations, and ICU admissions and their 95% CIs. In addition, we estimated the model-predicted counts of ED visits, hospitalizations, and ICU admissions per 1000 observations. For all statistical models, we assessed the multicollinearity of predictor variables using the variance inflation factor and accounted for the correlation of repeated observations. The analyses were performed using statistical software (SAS, version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc). All results were considered statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

Patient Demographics

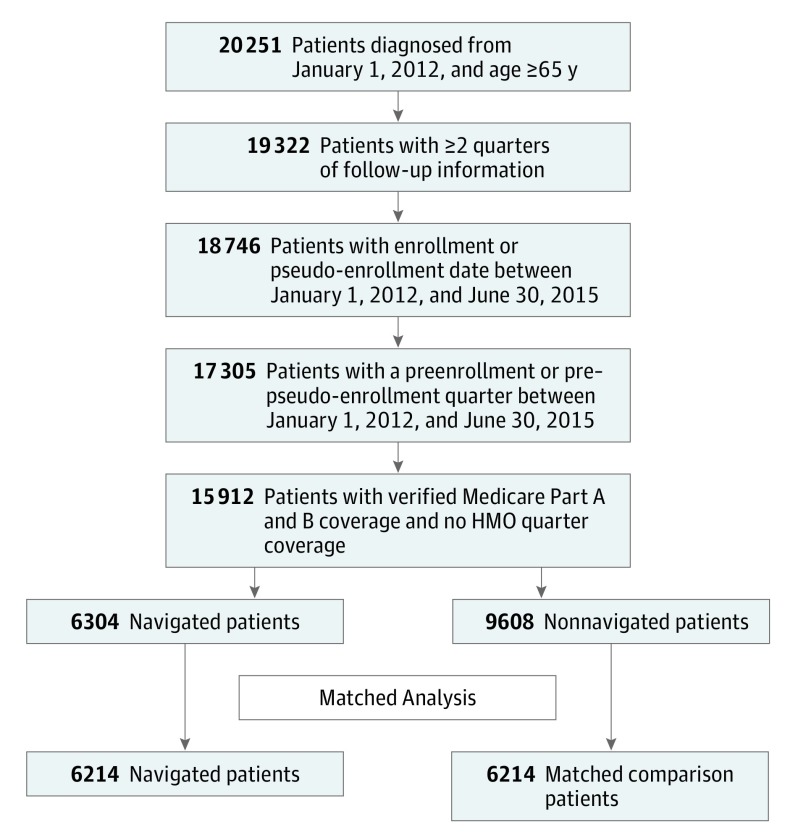

We identified 12 428 patients, 6214 in the navigated group and 6214 in the matched comparison group (Figure 1). Before matching, the navigated patients were more likely to have a high-acuity cancer, an advanced stage of cancer, and a higher comorbidity score and to have received chemotherapy during the study than nonnavigated patients (Table 1). The mean (SD) age at cancer diagnosis was 75 (7) years (Table 1). Approximately 12% of the participants were African American. After the match, navigated patients were still more likely to have received chemotherapy during the study (26.5% vs 20.1%, P < .001).

Figure 1. Study Population Exclusion Cascade.

HMO indicates health maintenance organization.

Table 1. Demographics of Navigated and Nonnavigated Geriatric Medicare Beneficiaries With Cancer in the Matched and Unmatched Groups (2012-2015).

| Variable | Unmatched Groups (n = 15 912) |

Matched Groups (n = 12 428) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonnavigated Patients (n = 9608) |

Navigated Patients (n = 6304) |

P Valuea | Matched Comparison Patients (n = 6214) |

Navigated Patients (n = 6214) |

P Valuea | |

| Age, mean (SD), yb | 74.7 (7.0) | 74.7 (6.7) | .62 | 74.8 (6.9) | 74.7 (6.7) | .34 |

| Race, % | ||||||

| Black | 12.0 | 12.6 | .56 | 12.4 | 12.4 | .96 |

| White | 86.5 | 86.0 | 86.1 | 86.1 | ||

| Other | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | ||

| Sex, % | ||||||

| Female | 51.0 | 51.4 | .84 | 52.4 | 51.4 | .27 |

| Male | 48.4 | 48.4 | 47.4 | 48.3 | ||

| Missing | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||

| Cancer acuity, %c | ||||||

| High | 37.5 | 39.8 | .003 | 39.9 | 40.0 | .94 |

| Low | 62.5 | 60.2 | 60.1 | 60.0 | ||

| Cancer stage, % | ||||||

| 0-I | 36.2 | 16.9 | <.001 | 35.6 | 16.9 | <.001 |

| II | 18.2 | 11.7 | 18.0 | 11.8 | ||

| III | 13.0 | 9.9 | 13.2 | 9.9 | ||

| IV | 14.9 | 11.2 | 15.7 | 11.1 | ||

| Missing | 17.7 | 50.3 | 17.5 | 50.3 | ||

| Phase of care, %b | ||||||

| Initial | 76.2 | 71.5 | <.001 | 73.2 | 72.6 | .41 |

| Survivor | 5.7 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 8.2 | ||

| End of life | 18.0 | 19.0 | 18.4 | 19.3 | ||

| Comorbidity score, %d | ||||||

| 0 | 25.4 | 23.4 | <.001 | 24.3 | 23.4 | .41 |

| 1 | 23.4 | 21.7 | 22.1 | 21.6 | ||

| 2-3 | 26.9 | 29.0 | 28.2 | 29.1 | ||

| ≥4 | 24.2 | 25.8 | 25.4 | 25.9 | ||

| Any chemotherapy, %e | 17.1 | 27.0 | <.001 | 20.1 | 26.5 | <.001 |

| Preenrollment Medicare costs per quarter, mean (SD), $ | 6256 (11 651) |

6697 (10 682) |

.01 | 6629 (11 614) |

6612 (10 628) |

.93 |

| Preenrollment ED visits, % | 19.8 | 20.1 | .62 | 20.4 | 20.2 | .82 |

| Preenrollment ICU admissions, % | 3.6 | 3.0 | .04 | 3.1 | 3.0 | .76 |

| Preenrollment chemotherapy, % | 9.6 | 15.5 | <.001 | 13.9 | 14.3 | .55 |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

By χ2 tests and t tests.

At index cancer diagnosis.

High acuity defined as brain, pancreatic, ovarian, lung, and head and neck or any stage IV cancer.

Weighted.

At any time between quarters 1 and 14.

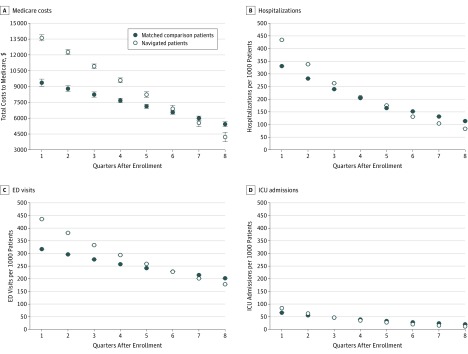

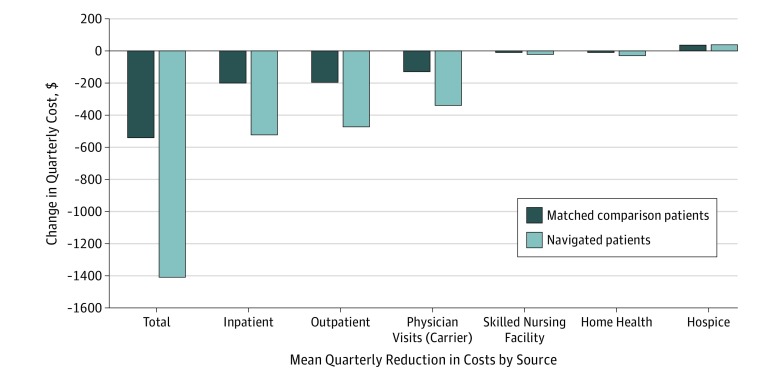

Medicare Costs

We observed statistically significant group × time interactions for Medicare costs and health care use (Table 2). Costs for the navigated group started higher but declined faster than the matched comparison group by $781.29 more per quarter per navigated patient (P < .001), for an estimated $19 million decline per year across the network, ultimately becoming lower for navigated patients after 6 quarters (Figure 2A). Inpatient and outpatient costs had the largest between-group quarterly declines, at $294 and $275, respectively, per patient. The greatest mean quarterly cost declines were observed for inpatient costs, which decreased by $522 and $198, respectively, per quarter per patient for navigated and matched comparison groups (Figure 3). Quarterly reductions per patient were also observed for outpatient costs ($473 for the navigated group and $194 for the matched comparison group) and physician visit (carrier) costs ($339 for the navigated group and $129 for the matched comparison group), while hospice costs increased ($39 for the navigated group and $36 for the matched comparison group) for navigated patients.

Table 2. Results of Regression Analyses on Medicare Costs and Health Care Usea.

| Outcome | β (SE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group × Timeb | Time | Groupb | |

| Total cost, $ | −781.29 (45.77) | −561.82 (30.99) | 5030.67 (247.87) |

| No. of ED visits, IRR (95% CI) | 0.94 (0.92-0.96) | 0.96 (0.94-0.97) | 1.56 (1.44-1.70) |

| No. of hospitalizations, IRR (95% CI) | 0.92 (0.90-0.94) | 0.90 (0.88-0.91) | 1.66 (1.53-1.81) |

| No. of ICU admissions, IRR (95% CI) | 0.90 (0.86-0.94) | 0.87 (0.85-0.90) | 1.62 (1.38-1.91) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

The model was adjusted for calendar time (P < .001 for all comparisons).

Navigated patients vs matched comparison patients.

Figure 2. Model-Estimated Medicare Costs and Health Care Use After Enrollment for Navigated Patients and Pseudo-Enrollment for Matched Comparison Patients.

ED indicates emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 3. Changes in Quarterly Costs by Component.

The mean reductions in Medicare costs are shown.

Resource Use

We observed decreases in resource use for the navigated group compared with the matched comparison group (Table 2). The group × time interactions indicate that, compared with the matched comparison group, the navigated group’s ED visits decreased by 6.0% more per quarter (IRR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92-0.96; P < .001), hospitalizations declined by 7.9% more per quarter (IRR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.90-0.94; P < .001), and ICU admissions were reduced by 10.6% more per quarter (IRR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.86-0.94; P < .001). Figure 2B, C, and D show the changes in predicted counts (per 1000 observations) for ED visits, hospitalizations, and ICU admissions.

Return on Investment

Costs among the navigated patients declined a mean of $781.29 more per patient per quarter than among the nonnavigated patients, which could be estimated as a $475 024 reduction in cost annually for a navigator managing 152 patients throughout the year. For a navigator with an annual salary investment of $48 448 (salary and fringe benefits), we estimated a return on investment of 1:10.

Discussion

In this population of geriatric patients with cancer, we observed substantial reductions in resource use and cost for navigated patients in the PCCP compared with matched nonnavigated patients. This influence was observed for costs of hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and physician visits.

Despite clear benefits to patients from navigation, programs have struggled with sustainable methods because of a lack of financial support. The estimated potential 1:10 return on investment of the PCCP helps make a financial case to organizational leadership for sustainability of navigation programs. The observed benefit is likely because of the PCCP approach of targeting high-risk, high-cost patients and patients who have unmet needs, which is reflected in the differences observed between the navigated and nonnavigated patients in our study. Navigators are uniquely positioned to meet the needs of these high-risk patients and help them better use outpatient resources. Unlike physicians and nursing staff, navigators are not limited by the traditional model of clinic-based care. They engage patients during clinical encounters with health care professionals and between appointments through frequent telephone communication. Navigators connect patients and their caregivers to appropriate resources across multiple disciplines, in different health care settings, and within the community at large. This patient-centered, preventive, proactive approach has the potential to lead to increased patient activation and earlier management of symptoms, decreasing the likelihood of unplanned admissions or inefficient care. Our findings support this hypothesis.

While we observed cost declines across all use sources, costs increased for hospice use, which may be secondary to navigators facilitating earlier conversations about goals of care and care preferences. The combination of reduced use of resources and increased hospice use achieved by the PCCP is consistent with other medical home, care transition, and palliative and supportive care interventions, which provide more appropriate support for patients with cancer, including those approaching the end of life. The PCCP is a model of navigation that supports patients throughout the cancer care continuum and may be a mechanism to extend palliative and supportive care more fully into the community, particularly in rural areas that lack palliative care resources.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the interpretation of findings in our study. First, there was no random assignment to the PCCP and the comparison group, and high-risk patients were targeted for the PCCP enrollment. To minimize the differences in patient characteristics because of the lack of randomization and the targeting of high-risk patients for enrollment, we used propensity score matching and considered use before enrollment (or a pseudo-enrollment date for the comparison group). However, unmeasured confounding factors, such as patient social support and level of engagement in their health, may also influence the likelihood of navigation, as well as patient outcomes. The intensity of navigation services also varied by patient and by need, making it challenging to identify the benefit for individual patients. In addition, navigated patients often had missing cancer stage information, particularly in the initial phase of care, because the tumor registries lack real-time case abstraction.

Second, the 12 institutions shared data, continuously monitored claims-based outcomes, and received reports and education by the PCCP leadership team based on navigator-collected and claims data. The creation of this learning collaborative may have influenced cost and resource use declines because of local culture shifts that occurred as a result of the PCCP. Although culture change was not systematically evaluated, the UAB leadership team received anecdotal reports of health systems changing telephone protocols, adding same-day sick visits, and redirecting charitable contributions to navigator-identified patient needs.

Third, the long-term influence of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on health care use and cost is yet to be determined. Analysis of trends in health care spending suggests that costs are rising less rapidly, but reductions in cost have not been reported nationally. To attempt to address this limitation, we adjusted for calendar time in our regression models.

Even with the encouraging cost trends reported herein, the PCCP is not sustainable within the current fee-for-service payment model, which does not reward coordination of care. Despite the requirement to provide navigation services for American College of Surgeons accreditation, such services are not billable, and savings to Medicare from decreased use lead to decreased revenue for the health system. Without transition to a value-based payment system that aligns payment with high-quality, cost-efficient, and connected delivery of care, health systems will not be incentivized to expand or even implement navigation services. However, given the apparent success of the PCCP, the ongoing Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Oncology Care Model, and the proposed Patient-Centered Oncology Payment model by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, change in payment models appear to be upon us.

Conclusions

There was a significant decline in costs and resource use for navigated geriatric patients with cancer within the PCCP compared with matched nonnavigated patients. Overall, cost reductions were driven by substantial declines in hospitalizations and clinic-based services. This model has the potential to reach the Triple Aim of improved health care, better health, and lower costs and significantly enhanced health care delivery in the United States as health systems transition to value-based health care.

eTable. HCPCS Codes for Emergency department and Intensive Care Unit Visits

References

- 1.Squires D, Anderson C. U.S. health care from a global perspective: spending, use of services, prices, and health in 13 countries. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2015;15:1-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The Triple Aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society of Clinical Oncology The state of cancer care in America, 2014: a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(2):119-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitka M. IOM report: aging US population, rising costs, and complexity of cases add up to crisis in cancer care. JAMA. 2013;310(15):1549-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM, eds. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman HP. Patient navigation: a community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21(1)(suppl):S11-S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman HP. Patient navigation: a community based strategy to reduce cancer disparities. J Urban Health. 2006;83(2):139-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):237-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Natale-Pereira A, Enard KR, Nevarez L, Jones LA. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer. 2011;117(15)(suppl):3543-3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krok-Schoen JL, Brewer BM, Young GS, et al. . Participants’ barriers to diagnostic resolution and factors associated with needing patient navigation. Cancer. 2015;121(16):2757-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fouad M, Wynn T, Martin M, Partridge E. Patient navigation pilot project: results from the Community Health Advisors in Action Program (CHAAP). Ethn Dis. 2010;20(2):155-161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Post DM, McAlearney AS, Young GS, Krok-Schoen JL, Plascak JJ, Paskett ED. Effects of patient navigation on patient satisfaction outcomes. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(4):728-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. ; Writing Group of the Patient Navigation Research Program . Impact of patient navigation on timely cancer care: the Patient Navigation Research Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall JK, Mbah OM, Ford JG, et al. . Effect of patient navigation on breast cancer screening among African American Medicare beneficiaries: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):68-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodday AM, Parsons SK, Snyder F, et al. . Impact of patient navigation in eliminating economic disparities in cancer care. Cancer. 2015;121(22):4025-4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888-1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocque GB, Barnett AE, Illig LC, et al. . Inpatient hospitalization of oncology patients: are we missing an opportunity for end-of-life care? J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(1):51-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleeland CS, Zhao F, Chang VT, et al. . The symptom burden of cancer: evidence for a core set of cancer-related and treatment-related symptoms from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns study. Cancer. 2013;119(24):4333-4340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedlund N, Risendal BC, Pauls H, et al. . Dissemination of patient navigation programs across the United States. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(4):E15-E24. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a505ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocque GB, Partridge EE, Pisu M, et al. . The Patient Care Connect Program: transforming health care through lay navigation. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(6):e633-e642. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.008896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey R, Drzayich Jankus D, Mosley D; UnitedHealthcare. Random assignment of proxy event dates to unexposed individuals in observational studies: an automated technique using SAS. http://www.mwsug.org/proceedings/2012/PH/MWSUG-2012-PH02.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed August 4, 2016.

- 22.Rocque GB, Taylor RA, Acemgil A, et al. ; Patient Care Connect Group . Guiding lay navigation in geriatric patients with cancer using a distress assessment tool. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(4):407-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rocque GB, Partridge EE, Pisu M, et al. . The Patient Care Connect Program: transforming health care through lay navigation. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(6):e633-e642. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.008896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinney RL, Lemon SC, Person SD, Pagoto SL, Saczynski JS. The association between patient activation and medication adherence, hospitalization, and emergency room utilization in patients with chronic illnesses: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(5):545-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? an examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):520-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell SE, Gardiner PM, Sadikova E, et al. . Patient activation and 30-day post-discharge hospital utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):349-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. . Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes SL, Weaver FM, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. ; Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Home-Based Primary Care . Effectiveness of team-managed home-based primary care: a randomized multicenter trial. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2877-2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822-1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorenzoni L, Belloni A, Sassi F. Health-care expenditure and health policy in the USA versus other high-spending OECD countries. Lancet. 2014;384(9937):83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClellan MB, Thoumi AI. Oncology payment reform to achieve real health care reform. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):223-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobsen PB, Ransom S. Implementation of NCCN distress management guidelines by member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5(1):99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clough JD, Kamal AH. Oncology Care Model: short- and long-term considerations in the context of broader payment reform. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(4):319-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Society of Clinical Oncology Patient-Centered Oncology Payment: payment reform to support higher quality, more affordable cancer care. https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/advocacy-and-policy/documents/asco-patient-centered-oncology-payment.pdf. Published May 2015. Accessed September 28, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. HCPCS Codes for Emergency department and Intensive Care Unit Visits