ABSTRACT

E-selectin is a key mediator of breast cancer cell (BCC) metastatic entry into the bone and stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) is a critical molecular anchor for BCCs within discrete pro-dormancy bone marrow (BM) niches. Small-molecule inhibitors blocked metastatic entry and mobilized established disease from BM, suggesting a new treatment strategy to prevent breast cancer relapse.

KEYWORDS: AMD-3100, breast cancer, bone metastasis, E-selectin, GMI-1271, SDF-1

Abbreviations

- BCC

breast cancer cell

- BM

bone marrow

- CXCR4

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4

- ER

estrogen receptor

- SDF-1

stromal-derived factor 1

Breast cancer accounts for 14% of total cancer-related deaths worldwide despite the continuing development of novel targeted therapies against the disease.1 Patients that receive an early diagnosis of localized disease, primary tumor resection, and even an aggressive chemotherapy regimen, remain susceptible to late metastatic relapse. The bone marrow (BM), specifically, is a very attractive site for breast cancer metastases, with the bone being the first site of metastatic progression in 50% of patients with relapse.2 More than 30% of patients with early-stage disease have been shown to have detectable micrometastases in the bone, which correlates with a negative prognostic outlook for both overall and disease-free survival.3 The specific molecular mechanism through which breast cancer cells (BCCs) migrate to and gain entry into the BM are unknown. The factors within the BM microenvironment that support the indolent progression and chemotherapy evasion of micrometastases, which precipitate distant disease relapse, also remain undefined. A recent publication in Science Translational Medicine has identified key mediators of BCC trafficking in the bone and small-molecule antagonists that effectively inhibit BCC homing as well as the mobilization of established micrometastatic disease out of the BM and into the circulation.4

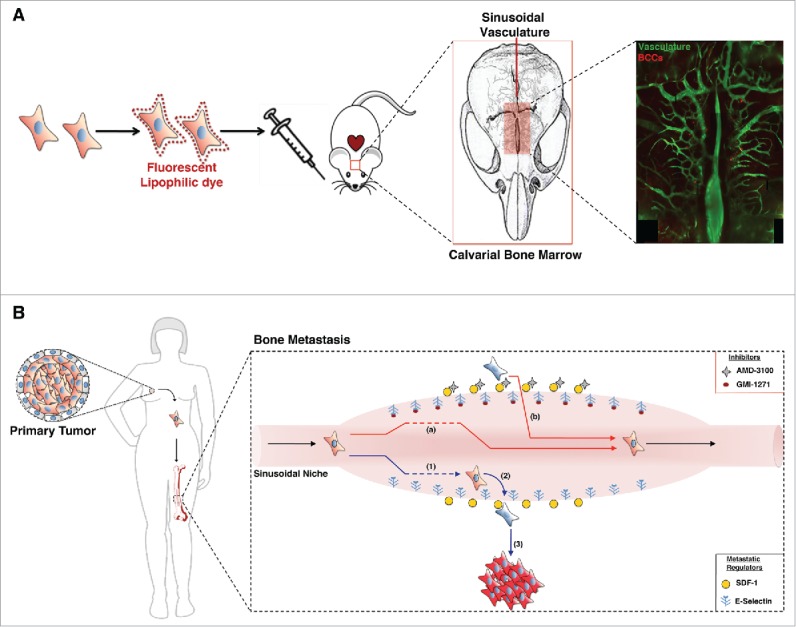

Previous observations had demonstrated that both benign and malignant hematopoietic cells home to the BM via defined sinusoidal vascular gateways that express high levels of the adhesion molecule E-selectin and the chemokine stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1).5 The initial study hypothesis proposed that bone metastatic BCCs co-opt these same molecular pathways. A multivariate analysis of 29 genes corresponding to SDF-1 and E-selectin ligands and associated post-translational processing was applied to a previously defined breast tumor data set containing gene expression analysis from 4,767 primary tumor patient samples.6 Elevated levels of expression of this gene set were highly correlated with a subgroup of “late-relapse” patients (≥5 years post remission). To investigate whether this correlation has functional relevance a preclinical xenograft model of breast cancer metastasis was employed (Fig. 1A). Real-time in vivo confocal microscopy of fluorescent BCCs was performed at various time points after intracardiac engraftment. This methodology allowed anatomic localization of BCCs in the calvarial BM with single-cell resolution, as well as video-rate imaging of BCCs in transit in the bloodstream.

Figure 1.

E-selectin and SDF-1: key mediators of breast cancer cell trafficking in the bone. (A) Breast cancer metastatic model. The xenograft model of breast cancer metastasis employed for in vivo video-rate confocal imaging of the mouse calvarial bone marrow (BM) and vasculature. Following intracardiac engraftment of fluorescently labeled breast cancer cells (BCCs), their presence in the circulation, transit into and out of the bone, and localization and proliferation within the BM was tracked in real time with single-cell resolution. (B) Schematic model of BCC metastasis mediated by E-selectin and stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and small-molecule mediated antagonism of this process. BCCs migrate from the primary tumor site and can home to the E-selectin+ sinusoidal niche in the bone (1). SDF-1 tethers BCCs within this pro-dormancy niche (2), whereas BCC proliferation occurs in distant anatomic locations (3). GMI-1271, a specific inhibitor of E-selectin, significantly diminished BCC entry into the bone (a) and AMD-3100, a SDF-1/C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) antagonist, successfully mobilized established disease out of the pro-dormancy niche (b).

BM homing experiments using a panel of estrogen receptor positive (ER+) and estrogen receptor negative (ER−) BCC lines revealed that these cells entered the BM and resided in a dormant state within distinct E-selectin+/SDF-1+ sinusoidal vasculature niches, with ER+ cell lines shown to have greater BM homing capacity. Because SDF-1 is expressed in organs that are sites of breast cancer metastasis, including the lung, liver, brain, and bone, prevailing hypotheses have held that SDF-1 mediates BCC homing to BM.7 Price et al. therefore analyzed the relationship between SDF-1 and BCC BM homing potential in vivo. However, in a panel of BCC cell lines the level of surface expression of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), the SDF-1 receptor, did not correlate with BM homing capacity. Moreover, a variety of SDF-1/CXCR4 inhibitory strategies, including CXCR4 antagonism using the drug AMD-3100, had no effect on BM homing. In contrast to this result, E-selectin was revealed to be a key mediator of BM homing. Pretreatment of mice with the specific E-selectin antagonist GMI-1271 had a profound inhibitory effect on BCC BM homing. This inhibitory effect was maintained in the stem cell population (CD-44+/CD-24−/low) of ER+ MCF-7 cells and in alternative orthotopic models of metastasis.

Although SDF-1 did not have a role in mediating BM homing of BCCs, its expression helped retain BCCs within the pro-dormancy sinusoidal niche. In long-term tumor engrafted mice, the vast majority of BCCs present in SDF-1+ sinusoids were dormant (retaining fluorescent membrane label), whereas cell proliferation was observed to initiate in distant lateral regions of the calvarial BM, away from the medial pro-dormancy sinusoids. The tethering function of SDF-1 on BCCs was blocked in vivo by AMD-3100 administration. A single dose of AMD3100 was effective in mobilizing newly homed and, most excitingly, established dormant micrometastases out of the BM and into circulation.

These preclinical observations were corroborated through the analysis of primary human patient samples. Homing experiments performed using in vitro expanded primary human breast cancer cells confirmed that primary human BCCs entered the BM through the same sinusoidal vascular gateways and were dependent on E-selectin for homing. Immunohistochemical analysis of BM core biopsies from breast cancer patients with bone micrometastatic disease revealed that BCCs were preferentially localized close to sinusoidal vasculature and that these metastases were indolent (Ki67−). In patients with bone micrometastases, perisinusoidal BCCs were still Ki67−, while Ki67+ BCCs were identified in alternative anatomical regions.

These data support a revised model for breast cancer metastasis to bone: BCCs intravasate from the primary tumor into the circulation and gain entry into bone through interactions with E-selectin in the sinusoidal vasculature niche (Fig. 1B). SDF-1 facilitates retention of BCCs in the niche. Stromal factors, potentially including SDF-1, can maintain dormant BCCs in a chemoresistant state for a prolonged period8 until the cells migrate away from this pro-dormancy niche, initiating tumor proliferation and disease relapse. This work also identified strategies and potential efficacious agents for antagonizing BCC bone trafficking. A combinatorial treatment strategy employing conventional adjuvant therapies with inhibition of both SDF-1 and E-selectin could be one effective approach. Dormant micrometastases that are mobilized out of protective stromal niches by AMD-3100 and prevented from homing back to these niches by GMI-1271 could become more susceptible to chemotherapy or hormonal therapies. In addition, prolonged detachment from the stroma could itself induce programmed cell death in mobilized BCCs. This approach, which would add minimal toxicity to current treatment regimens, could eradicate bone metastases that harbor the potential for late-stage relapse. GMI-1271 is currently under evaluation in phase 1 and 2 trials in acute myeloid leukemia,9 while AMD-3100 (Plerixafor) is already approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells for BM transplantation.10 Although preclinical investigation of the sinusoidal niche, the E-selectin/ligand synapse in BCCs, and the ultimate fate of mobilized BCCs in breast cancer bone metastasis is continuing, this report by Price et al. proposes a specific and actionable strategy for the eradication of BM micrometastasis that has clinical potential in the near future.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61:69-90; PMID:21296855; https://doi.org/ 10.3322/caac.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrahim T, Mercatali L, Amadori D. A new emergency in oncology: Bone metastases in breast cancer patients (Review). Oncol Lett 2013; 6:306-10; PMID:24137321; https://doi.org/ 10.3892/ol.2013.1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun S, Vogl FD, Naume B, Janni W, Osborne MP, Coombes RC, Schlimok G, Diel IJ, Gerber B, Gebauer G, et al.. A pooled analysis of bone marrow micrometastasis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:793-802; PMID:16120859; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa050434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price TT, Burness ML, Sivan A, Warner MJ, Cheng R, Lee CH, Olivere L, Comatas K, Magnani J, et al.. Dormant breast cancer micrometastases reside in specific bone marrow niches that regulate their transit to and from bone. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8:340ra73; PMID:27225183; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad4059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sipkins DA, Wei X, Wu JW, Runnels JM, Côté D, Means TK, Luster AD, Scadden DT, Lin CP. In vivo imaging of specialized bone marrow endothelial microdomains for tumour engraftment. Nature 2005; 435:969-73; PMID:15959517; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature03703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng Q, Chang JT, Gwin WR, Zhu J, Ambs S, Geradts J, Lyerly HK. A signature of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity and stromal activation in primary tumor modulates late recurrence in breast cancer independent of disease subtype. Breast Cancer Res 2014; 16:407; PMID:25060555; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s13058-014-0407-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, et al.. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature 2001; 410:50-6; PMID:11242036; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/35065016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin FT, Dwyer RM, Kelly J, Khan S, Murphy JM, Curran C, Miller N, Hennessy E, Dockery P, Barry FP, et al.. Potential role of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the breast tumour microenvironment: stimulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 124:317-26; PMID:20087650; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10549-010-0734-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GlycoMimeticsInc Study to Determine Safety, Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of GMI-1271 in Combination With Chemotherapy in AML. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]: National Library of Medicine (US). (2014- [cited 2016 June 20th]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT02306291 NLM Identifier:NCT02306291) [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiPersio JF, Stadtmauer EA, Nademanee A, Micallef IN, Stiff PJ, Kaufman JL, Maziarz RT, Hosing C, Früehauf S, Horwitz M, et al.. Plerixafor and G-CSF versus placebo and G-CSF to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells for autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood 2009; 113, 5720-5726; PMID:19363221; https://doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]