Illicit drug use is widely accepted as an absolute contraindication to many advanced medical therapies such as transplantation. Clinical practice guidelines list active or recent illicit drug use as a class III recommendation for heart transplantation and durable mechanical circulatory support. After heart transplantation, patients with a history of substance abuse have significant increases in noncompliance (38.3% vs 6.3%, p = 0.0001), death because of non-compliance (27.7% vs 2.1%, p = 0.0004), and heart-related death (44.7% vs 24.7%, p = 0.017).1 For this reason, candidates for heart transplantation are routinely screened for use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs starting with urine immunoassay drug screens (UDS).

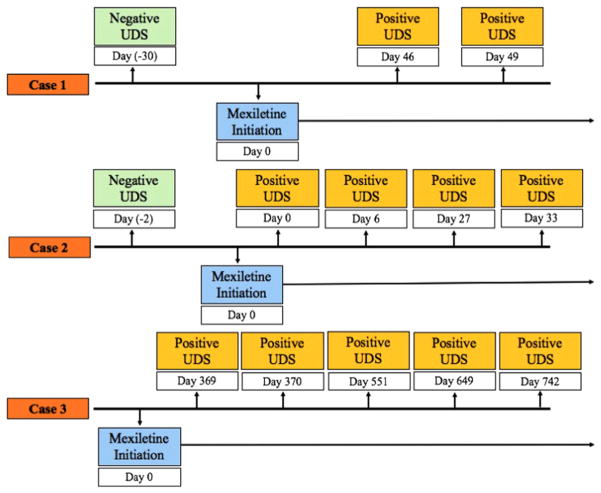

Patients with advanced heart failure commonly have ventricular arrhythmias treated with antiarrhythmics, such as mexiletine. We report the first evidence of mexiletine being associated with false-positive UDS for amphetamines in 3 patients with advanced heart failure being considered for transplantation (cases are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1). All cases had negative confirmatory testing, correlated with the initiation of mexiletine, and involved patients who were not taking any other medications known to cause false-positive results. Given the high prevalence of drug and alcohol abuse, it is not surprising that on detailed social history all 3 patients described a previous history of substance abuse, further complicating assessment of current use and risks after transplantation.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 44 | 53 | 66 |

| Etiology | Ischemic cardiomyopathy | Ischemic cardiomyopathy | Non-ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| Initial indication for left ventricular assist device | Bridge to transplant | Destination therapy | Destination therapy |

| Substance abuse history | Tobacco | Tobacco | Tobacco |

| Alcohol | Alcohol | Alcohol | |

| Opiates | |||

| Confirmatory testing | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Type of arrhythmia | Ventricular tachycardia | Ventricular tachycardia | Ventricular tachycardia |

| Antiarrhythmics | Mexiletine 150 mg 3 times daily | Mexiletine 150 mg 3 times daily | Mexiletine 150 mg 3 times daily |

| Other medications (including over-the-counter) | Acetaminophen | Acetaminophen | Alendronate |

| Aspirin | Ascorbic acid | Allopurinol | |

| Cholecalciferol | Aspirin | Ascorbic acid | |

| Citalopram | Bumetanide | Aspirin | |

| Docusate sodium | Cholecalciferol | Calcium carbonate–vitamin D3 | |

| Furosemide | Ferrous sulfate | Ergocalciferol | |

| Gabapentin | Levothyroxine | Esomeprazole | |

| Levetiracetam | Losartan | Ferrous sulfate | |

| Magnesium oxide | Melatonin | Insulin | |

| Nitroglycerin | Mexiletine | Levothyroxine | |

| Oxycodone | Oxycodone | Magnesium oxide | |

| Pantoprazole | Pantoprazole | Mycophenolate | |

| Polyethylene glycol | Spironolactone | Nystatin | |

| Potassium chloride | Potassium chloride | ||

| Senna | Pravastatin | ||

| Spironolactone | Prednisone | ||

| Warfarin | Tacrolimus | ||

| Valganciclovir |

Figure 1.

Timing of mexiletine initiation of positive urine drug screens.

Although the results of immunoassay testing are binary, interpretation is often not straightforward. Immunoassays, commonly used in UDS, employ antibodies designed to recognize either the drug of interest or its metabolites. Immunoassay false-positive results depend primarily on the cross-reactivity profile of immunoassays used and the specific substance in question. The various forms of immunoassays include cloned enzyme donor immunoassay, enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique, fluorescence polarization immunoassay, and radioimmunoassay.2 Our center uses the Beckman Coulter Emit II Plus Amphetamines Assay, which is run on Beckman AU5800 Platform (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA). False-positive immunoassay results for amphetamines and methamphetamines are the most common among UDS with common culprits being over-the-counter medications (i.e., antihistamines, decongestants, histamine-2 antagonists, energy supplements), antipsychotics, and antidepressants (Table 2).3,4 Mexiletine is structurally similar to amphetamine and methamphetamine, containing a benzene ring with a hydrocarbon tail that terminates with a functional amine group (Figure 2). This structural similarity likely explains the false-positive amphetamine immunoassay result. In addition, amphetamine and methamphetamine are simple molecules, which makes it difficult to design specific antibodies and increases the potential for cross-reactivity.4

Table 2.

Agents Causing False-Positive Urine Immunoassay Results for Amphetamines

| Amantadine Benzphetamine Bupropion Chlorpromazine Clobenzorex Deprenyl Desipramine Dextroamphetamine Ephedrine Fenproporex Isometheptene Isoxsuprine Labetalol Levmetamfetamine (Vicks Vapor inhaler) Methamphetamine Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) Methylphenidate Phentermine Phenylephrine Phenylpropanolamine Promethazine Pseudoephedrine Ranitidine Ritodrine Selegiline Thioridazine Trazodone Trimethobenzamide Trimipramine |

Figure 2.

Structures of amphetamine, methamphetamine, and mexiletine.

It is important for providers to understand the various causes of false-positive UDS to avoid straining the provider-patient relationship, to select individuals who would benefit most from advanced therapies for heart failure, and to guide drug rehabilitation services. Confirmatory testing with a secondary specific laboratory technique, such as high-performance liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry, should be considered before making high-consequence clinical decisions based on immunoassay screen results.2

In summary, mexiletine can cause false-positive results for amphetamines on urine immunoassay. Providers should confirm results of UDS with a second laboratory method.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

L.A.A. received support from National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant No. 5K23HL105896. A.M. receives support from National Institutes of Health Grant Nos. 1 K23 GM110516 and CTSI UL1 TR001082.

References

- 1.Hanrahan J, Eberly C, Mohanty P. Substance abuse in heart transplant recipients: a 10-year follow-up study. Prog Transplant. 2001;11:285–90. doi: 10.1177/152692480101100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moeller K, Lee K, Kissack J. Urine drug screening: practical guide for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:66–76. doi: 10.4065/83.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahm NC, Yeager LL, Fox MD, Farmer KC, Palmer TA. Commonly prescribed medications and potential false-positive urine drug screens. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:1344–50. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saitman A, Park HD, Fitzgerald RL. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: a review. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38:387–96. doi: 10.1093/jat/bku075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]