Abstract

Objectives To evaluate the effectiveness of policies and recommendations on folic acid aimed at reducing the occurrence of neural tube defects.

Design Retrospective cohort study of births monitored by birth defect registries.

Setting 13 birth defects registries monitoring rates of neural tube defects from 1988 to 1998 in Norway, Finland, Northern Netherlands, England and Wales, Ireland, France (Paris, Strasbourg, and Central East), Hungary, Italy (Emilia Romagna and Campania), Portugal, and Israel. Cases of neural tube defects were ascertained among liveborn infants, stillbirths, and pregnancy terminations (where legal). Policies and recommendations were ascertained by interview and literature review.

Main outcome measures Incidences and trends in rates of neural tube defects before and after 1992 (the year of the first recommendations) and before and after the year of local recommendations (when applicable).

Results The issuing of recommendations on folic acid was followed by no detectable improvement in the trends of incidence of neural tube defects.

Conclusions Recommendations alone did not seem to influence trends in neural tube defects up to six years after the confirmation of the effectiveness of folic acid in clinical trials. New cases of neural tube defects preventable by folic acid continue to accumulate. A reasonable strategy would be to quickly integrate food fortification with fuller implementation of recommendations on supplements.

Introduction

Improving children's survival and health worldwide requires effective primary prevention of birth defects. In many developed countries, birth defects already account for one in every four infant deaths and for an unknown number of fetal deaths and pregnancy terminations.1,2 However, because of their large birth population and the few resources available for treatment and rehabilitation, developing countries bear most of the global burden of birth defects.1

Primary prevention of certain serious birth defects is now feasible globally. The groundbreaking studies of Smithells and colleagues,3-5 confirmed by many other studies and randomised clinical trials by the early 1990s,6-9 showed that supplements containing folic acid, a B vitamin, when consumed from before conception, can reduce spina bifida and other neural tube defects by an estimated 80% or more. Neural tube defects, which also include anencephaly, are severe and often lethal conditions that annually affect at least 300 000 newborns worldwide.1,7,10 Accumulating data indicate additional benefits of folic acid on other major birth defects.11

Because folic acid is inexpensive, safe, and easy to use, many professional organisations and some governmental agencies promote the use of folic acid supplements to prevent neural tube defects. The format of such recommendations varies, but they typically include statements that women should eat a healthy diet and take folic acid supplements when planning a pregnancy or throughout childbearing age. In a few countries, including the United States, Canada, Chile, and South Africa, recommendations to consume folic acid are integrated with a policy of wide-spread fortification of flour to ensure that the entire population receives at least a small additional amount of folic acid regardless of access to supplements. This population-wide approach is effective,12-14 but it is used in only a few countries.

A crucial question is how effective are recommendations alone, in the absence of fortification. We examined this question by evaluating rates of neural tube defects and their temporal relation with recommendations on folic acid.

Methods

The study included selected registries from the International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Monitoring Systems. Major criteria for inclusion were a structure for population based ascertainment; relatively large size; and ability to provide detailed case information for central clinical review, ascertain affected pregnancy terminations (where such a procedure was legal), and conduct an assessment of local folic acid policy development. The nature of the funding sources, primarily from Europe, led to the preferential inclusion of European registries. Although initially included, US registries were later excluded because of the introduction of fortification of flour. We gathered information on folic acid recommendations from interviews, publications listed on Medline, reports of workshops and committees, and documents issued by governmental agencies and professional bodies.

Thirteen registries provided listings of cases of anencephaly or spina bifida among liveborn infants, stillbirths, and pregnancy terminations that occurred between 1988 and 1998. Case information also included birth outcome, birth date, gestational age, and associated malformations. Registries also provided appropriate denominator information.

To adjust for temporal and geographical variations in the timing of pregnancy terminations, we assigned affected pregnancy terminations to the calendar year in which they would have been delivered had they reached the mean gestational age of liveborn cases in the database (adjusted by registry and birth year). We use the term “incidence” for the reported rates, although the true population at risk for neural tube defects (all conceptuses) cannot be ascertained.

We plotted incidences by year, programme, and type of neural tube defect (anencephaly and spina bifida). We used Poisson regression to assess trends. From the Poisson regression, we derived for each programme an incidence rate ratio, which estimates the average relative change in rate per year. For example, an incidence rate ratio of 1.00 indicates no change (a flat regression line), whereas a ratio of 0.80 indicates a 20% average decrease and a ratio of 1.20 indicates a 20% average increase from one year to the next.

We calculated incidence rate ratios for the entire study period as well as for before and after 1992 and before and after the year of introduction of national recommendations (where these had been issued). We chose 1992 because of the timing of the publication of the randomised trials (1991 and 1992) and of the recommendations in the United States and the United Kingdom (in 1992), which were internationally known and available to all interested parties. We used the incidence by year and by programme, derived from Poisson regression, diminished by the appropriate prevented fraction (30% to 90%), to estimate the number of cases that might have been prevented in the study area since 1992 at different levels of folic acid effectiveness.

Results

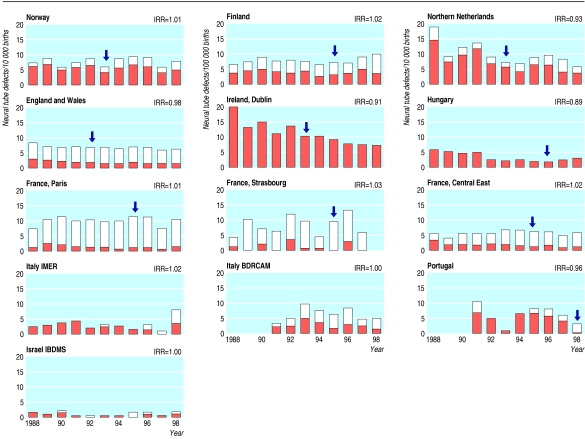

The study included 8636 cases of anencephaly or spina bifida among over 13 million births in 13 areas in Europe and Israel (table 1). Relative to other study areas, rates of neural tube defects tended to be higher in Ireland, Northern Netherlands, and France (Paris) (fig 1). Pregnancy terminations contributed considerably to reported rates in some registries (fig 1).

Table 1.

Study place and period, birth population, cases (including pregnancy terminations), and rates of neural tube defects

|

Births

|

Cases

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Coverage | Period | Total | Yearly* | No | Rate† |

| Norway | National | 1988-98 | 662 441 | 60 222 | 500 | 7.5 |

| Finland | National | 1988-98 | 697 687 | 63 426 | 537 | 7.7 |

| Northern Netherlands | Regional (three provinces) | 1988-98 | 205 653 | 18 696 | 196 | 9.5 |

| England and Wales | National (England and Wales) | 1988-98 | 7 424 798 | 674 982 | 4969 | 6.7 |

| Ireland | Regional (three counties, east Ireland) | 1988-98 | 209 997 | 19 091 | 240 | 11.4 |

| France, Paris | City (Greater Paris area) | 1988-98 | 406 140 | 36 922 | 404 | 9.9 |

| France, Strasbourg | City and surrounding area (Bas-Rhin) | 1988-97 | 134 063 | 13 406 | 114 | 8.5 |

| France, Central East | Regional | 1988-98 | 1 118 707 | 101 701 | 657 | 5.9 |

| Hungary | National | 1988-98 | 1 275 779 | 115 980 | 611 | 4.8 |

| Italy, Emilia Romagna | Regional (northern Italy) | 1988-98 | 271 494 | 24 681 | 100 | 3.7 |

| Italy, Campania | Regional (southern Italy) | 1991-8 | 351 166 | 43 896 | 234 | 6.7 |

| Portugal | Regional (three areas) | 1991-8 | 79 249 | 9 906 | 50 | 6.3 |

| Israel | Central area (three hospitals) | 1988-98 | 188 328 | 17 121 | 24 | 1.3 |

| Total | 13 025 502 | 1 200 030 | 8636 | 6.6 | ||

Average over study period.

Rate per 10 000 births.

Fig 1.

Rates of neural tube defects (anencephaly and spina bifida) per 10 000 births, 1988-98. Shaded top portion indicates terminated pregnancies. Arrow indicates time of recommendations in each country. IRR=average rate of change from one year to next

Folic acid policies during the study period varied from no recommendations (Italy and Israel) or dietary recommendations only (Norway until 1998) to dietary recommendations plus use of supplements among selected women (Finland) or use of supplements for women planning pregnancy or all women of childbearing age (table 2). The timing of the recommendations also varied, with some programmes—such as those in the United Kingdom and Ireland—issuing recommendations as early as 1992.

Table 2.

Type and timing of recommendations on folic acid in selected areas at end of study period

|

Highlights

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registry area | Year | Diet | Supplements | Comment | Issuing body |

| Europe: | |||||

| Norway | 1993

|

+

|

−

|

Folate rich diet recommended

|

Board of Health

|

| 1998 | + | + | Supplements recommended in 1998 | National Nutrition Council | |

| Finland | 1995 | + | +* | Supplements for selected groups* | Ministry of Social Affairs and Health |

| Netherlands | 1993 | + | + | Women planning pregnancy | Health and Food Council |

| United Kingdom | 1992 | + | + | Women planning pregnancy | Department of Health |

| Ireland | 1993 | + | + | Women planning pregnancy | Department of Health |

| France | 1995, 1997 | + | + | Women planning pregnancy | Paediatric Society (1995), Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (1997) |

| Hungary | 1996 | + | + | Women planning pregnancy | National Institute for Health Promotion |

| Italy | None | − | − | No official recommendation | None |

| Portugal | 1998 | + | + | Women of childbearing age | Directory of Health |

| Israel | None | − | − | (Issued in 2000) | |

Such as women with certain chronic illnesses (diabetes, seizures (on treatment)), using certain drugs, with a previous pregnancy affected by neural tube defect, and on very unbalanced diets.

In most areas rates were stable, as indicated by incidence rate ratios statistically undistinguishable from one (table 3). Four areas showed an overall decreasing trend (table 3). Trends after 1992 were similar to trends before 1992 (table 4). In Italy (Campania), trends seemed to vary across the two periods, but these variations were within statistical fluctuations. In Hungary, reported rates seemed to decrease then increase towards the end of the study period. A retrospective assessment identified underascertainment of affected pregnancy terminations in the mid-1990s due to organisational changes in the reporting system in Hungary, and for this reason we excluded pregnancy terminations from Hungarian data in the tables 4 and 5 and figures 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Average yearly rate of change in the occurrence rate of neural tube defects in study areas

|

Incidence rate ratio†(95% CI)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registry area* | Period | Births | Total neural tube defects | Spina bifida | Anencephaly |

| Norway | 1988-98 | 662 441 | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.06) |

| Finland | 1988-98 | 697 687 | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.07) | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.04) |

| Northern Netherlands (↓) | 1988-98 | 205 653 | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.97) | 0.90 (0.85 to 0.96) | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.07) |

| England and Wales (↓) | 1988-98 | 7 424 798 | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98) | 0.98 (0.97 to 1.00) |

| Ireland (↓) | 1988-98 | 209 997 | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.95) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98) | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.94) |

| France, Paris | 1988-98 | 406 140 | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.06) | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.04) |

| France, Strasbourg | 1988-97 | 134 063 | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.10) | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.17) | 1.00 (0.92 to 1.09) |

| France, Central East | 1988-98 | 1 118 707 | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.04) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06) | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.03) |

| Hungary (↓) | 1988-98 | 1 275 779 | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.96) | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.95) | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.04) |

| Italy, Emilia Romagna | 1988-98 | 271 494 | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.08) | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.04) | 1.37 (1.12 to 1.66) |

| Italy, Campania | 1991-8 | 351 166 | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.06) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.08) | 1.00 (0.92 to 1.08) |

| Portugal | 1991-8 | 79 249 | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.08) | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.12) | 0.94 (0.76 to 1.17) |

| Israel | 1988-98 | 188 328 | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.13) | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.19) | 0.98 (0.81 to 1.19) |

| Total | 13 025 502 | ||||

Arrow indicates areas with a decrease, on average, in rates of neural tube defects during the study period.

Can be interpreted as average change in rate per year (<1 indicates decreasing rates; >1 indicates increasing rates).

Table 4.

Average yearly change in rates of neural tube defects, after and before 1992

|

Total neural tube defects

|

Spina bifida

|

Anencephaly

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Period | Births | Cases | IRR*(95% CI) | Cases | IRR*(95% CI) | Cases | IRR*(95% CI) |

| Norway | 1993-8

|

360 906

|

277

|

1.00 (0.93 to 1.07)

|

169

|

1.04 (0.95 to 1.14)

|

108

|

0.94 (0.84 to 1.05)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 301 535 | 223 | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.12) | 145 | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.16) | 78 | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.18) | |

| Finland | 1993-8

|

371 826

|

289

|

1.07 (1.00 to 1.15)

|

179

|

1.05 (0.97 to 1.15)

|

110

|

1.10 (0.99 to 1.23)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 325 861 | 248 | 1.04 (0.96 to 1.14) | 134 | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.17) | 114 | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.19) | |

| Northern Netherlands | 1993-8

|

116 337

|

89

|

0.99 (0.87 to 1.11)

|

55

|

0.99 (0.85 to 1.15)

|

34

|

0.99 (0.81 to 1.20)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 89 316 | 107 | 0.91 (0.79 to 1.04) | 83 | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.14) | 24 | 0.71 (0.52 to 0.97) | |

| England and Wales | 1993-8

|

3 934 009

|

2485

|

0.97 (0.95 to 0.99)

|

1249

|

0.97 (0.94 to 1.00)

|

1236

|

0.97 (0.94 to 1.01)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 3 490 789 | 2484 | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 1317 | 0.96 (0.92 to 0.99) | 1167 | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.00) | |

| Ireland | 1993-8

|

113 719

|

99

|

0.92 (0.82 to 1.03)

|

59

|

0.92 (0.79 to 1.07)

|

40

|

0.92 (0.77 to 1.10)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 96 278 | 141 | 0.91 (0.81 to 1.02) | 74 | 0.94 (0.80 to 1.10) | 67 | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.03) | |

| France, Strasbourg | 1993-7

|

65 737

|

58

|

1.01 (0.84 to 1.22)

|

29

|

1.09 (0.84 to 1.41)

|

29

|

0.95 (0.73 to 1.22)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 68 326 | 56 | 1.16 (0.96 to 1.40) | 22 | 1.04 (0.78 to 1.40) | 34 | 1.25 (0.98 to 1.59) | |

| France, Paris | 1993-8

|

221 290

|

223

|

0.99 (0.92 to 1.07)

|

122

|

0.94 (0.85 to 1.05)

|

101

|

1.04 (0.93 to 1.17)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 184 850 | 181 | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.17) | 85 | 0.99 (0.85 to 1.16) | 96 | 1.11 (0.96 to 1.28) | |

| France, Central East | 1993-8

|

609 089

|

384

|

0.95 (0.89 to 1.01)

|

261

|

0.98 (0.91 to 1.05)

|

123

|

0.88 (0.79 to 0.98)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 509 618 | 273 | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.13) | 172 | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.14) | 101 | 1.07 (0.93 to 1.23) | |

| Hungary | 1993-8

|

650 371

|

244

|

1.04 (0.95 to 1.15)

|

174

|

1.03 (0.92 to 1.14)

|

70

|

1.13 (0.91 to 1.41)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 625 408 | 367 | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.94) | 283 | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.90) | 84 | 1.12 (0.91 to 1.38) | |

| Italy, Emilia Romagna | 1993-8

|

151 604

|

55

|

1.10 (0.93 to 1.29)

|

39

|

1.00 (0.82 to 1.21)

|

16

|

1.40 (1.01 to 1.95)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 119 890 | 45 | 1.09 (0.88 to 1.34) | 43 | 1.11 (0.90 to 1.37) | 2 | 0.75 (0.27 to 2.09) | |

| Italy, Campania | 1993-8

|

276 108

|

200

|

0.88 (0.81 to 0.96)

|

107

|

0.90 (0.80 to 1.00)

|

93

|

0.87 (0.77 to 0.98)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 75 058 | 34 | 1.46 (0.74 to 2.90) | 20 | 1.90 (0.76 to 4.77) | 14 | 1.02 (0.36 to 2.92) | |

| Portugal | 1993-1998

|

68 234

|

41

|

1.00 (0.83 to 1.21)

|

29

|

0.95 (0.76 to 1.18)

|

12

|

1.15 (0.79 to 1.67)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 11 015 | 9 | 0.49 (0.12 to 1.97) | 5 | 0.66 (0.11 to 3.92) | 4 | 0.33 (0.03 to 3.15) | |

| Israel | 1993-1998

|

103 924

|

13

|

1.15 (0.83 to 1.58)

|

8

|

1.07 (0.71 to 1.60)

|

5

|

1.29 (0.74 to 2.24)

|

| To 1992 (ref) | 84 404 | 11 | 0.82 (0.53 to 1.27) | 6 | 0.87 (0.49 to 1.56) | 5 | 0.75 (0.39 to 1.47) | |

Incidence rate ratio (IRR) estimates the average yearly change in rate (<1 indicates decreasing rates; >1 indicates increasing rates).

Table 5.

Average yearly change in rates of neural tube defects, after and up to local recommendations

|

Incidence rate ratio*(95% CI)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Period | Total neural tube defects | Spina bifida | Anencephaly |

| Norway | 1994-8

|

0.93 (0.85 to 1.02)

|

0.97 (0.86 to 1.08)

|

0.88 (0.76 to 1.02)

|

| 1988-93 | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.05) | 1.02 (0.90 to 1.15) | |

| Finland | 1996-8

|

1.18 (0.97 to 1.44)

|

1.24 (0.96 to 1.60)

|

1.11 (0.82 to 1.51)

|

| 1988-95 | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.04) | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.09) | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.02) | |

| Northern Netherlands | 1994-8

|

0.96 (0.82 to 1.13)

|

0.94 (0.77 to 1.15)

|

0.99 (0.76 to 1.29)

|

| 1988-93 | 0.88 (0.79 to 0.98) | 0.89 (0.78 to 1.01) | 0.85 (0.68 to 1.07) | |

| England and Wales | 1993-8

|

0.97 (0.95 to 0.99)

|

0.97 (0.94 to 1.00)

|

0.97 (0.94 to 1.01)

|

| 1988-92 | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 0.96 (0.92 to 0.99) | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.00) | |

| Ireland, Dublin | 1994-8

|

0.91 (0.78 to 1.06)

|

0.88 (0.72 to 1.07)

|

0.97 (0.75 to 1.24)

|

| 1988-93 | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.99) | 0.92 (0.81 to 1.05) | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.01) | |

| France, Strasbourg | 1996-7

|

0.44 (0.19 to 1.02)

|

0.36 (0.12 to 1.14)

|

0.57 (0.17 to 1.94)

|

| 1988-95 | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.13) | 1.03 (0.89 to 1.19) | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.17) | |

| France, Paris | 1996-8

|

0.96 (0.76 to 1.21)

|

0.78 (0.57 to 1.08)

|

1.21 (0.87 to 1.70)

|

| 1988-95 | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.12) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.09) | |

| France, Central East | 1996-8

|

0.96 (0.80 to 1.14)

|

0.99 (0.80 to 1.23)

|

0.87 (0.62 to 1.22)

|

| 1988-95 | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.11) | |

| Hungary | 1997-8

|

1.24 (0.72 to 2.14)

|

1.25 (0.68 to 2.29)

|

1.24 (0.38 to 4.05)

|

| 1988-96 | 0.85 (0.81 to 0.88) | 0.83 (0.80 to 0.87) | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.01) | |

Estimates the average yearly change in rate (<1 indicates decreasing rates; >1 indicates increasing rates.

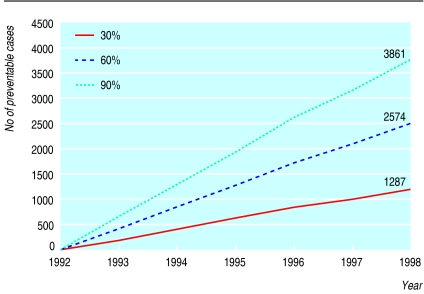

Fig 2.

Estimated number of pregnancies with neural tube defects preventable by folic acid in study area, 1993-8. Estimates assume three scenarios of effectiveness (30%, 60%, 90%), which encompass a reasonable range from low dose fortification to highly effective supplementation

We also saw no material change in trends after the issuing of local recommendations (table 5). Findings were similar for anencephaly and spina bifida separately and combined. The number of cases that might have been prevented in the study area beginning in 1993 ranged from 1287 (assuming 30% effectiveness), through 2574 (for 60% effectiveness), to 3861 (for 90% effectiveness) (fig 2).

Discussion

In this study covering more than 13 million births, rates of neural tube defects showed no detectable change associated with recommendations to consume more folic acid. Either rates were unchanged or the decline was similar to that observed during the period before the recommendations. From these data, we estimate that thousands of pregnancies that would otherwise have been healthy were affected by neural tube defects in the study area alone since 1992 (fig 2). These findings, which support and expand those from an earlier study conducted by Smithells and colleagues,15 underscore the ongoing missed opportunities for prevention well after the publication of the confirmatory randomised clinical trials and the first public health recommendations.

Limitations and strengths

The study has some potential limitations. Firstly, case ascertainment may have varied by registry and thus probably contributed to the geographical variation in reported rates (table 1). Incomplete ascertainment does not necessarily invalidate monitoring if it remains constant over time. Constant ascertainment is difficult to prove, and variations may have occurred, particularly among pregnancy terminations. In Hungary (fig 1), the apparent rapid decrease in rates of total neural tube defects in the early 1990s followed by a slight increase in the late 1990s was largely driven by the variation in reported affected pregnancy terminations. An ongoing retrospective evaluation (Siffel and Metneki, unpublished data) suggests that such variation coincided with organisational changes, now reversed, that mainly led to decreased reporting of pregnancy terminations.

A second limitation is that the use of ecological data may have led to real effects going undetected. Rates may have decreased locally, for example, in areas in the Netherlands and Ireland that conducted extensive educational campaigns,16,17 but we may have been unable to observe them, because of the nature of the data and limited sample size.

A third limitation is the study's limited geographical scope. The focus on European areas was related partly to the funding source and partly to the availability of data from relatively large and established registries with information on pregnancy terminations. A more comprehensive view would be desirable and useful. However, the study findings in Europe, where birth defects are a major contributor to infant death, are likely to be relevant to a more global discussion on missed opportunities for prevention of neural tube defects.

Finally, we had incomplete information on the extent of implementation of recommendations. Such information is crucial if we are to understand why recommendations did not reduce the incidence of disease.

The study also had several strengths. We included areas with a range of reported rates and recommendations, from none at all (Italy) to early adoption of recommendations in association with educational campaigns (for example, Ireland). The registries used multiple sources of ascertainment, including pregnancy terminations. Finally, the findings were not confounded by fortification of flour.

Possible explanations and implications

Why did recommendations have no detectable effect on rates, despite the proved effectiveness of folic acid? The most likely possibility is that recommendations were not implemented to the point of inducing a sustained change in behaviour in a sufficiently large proportion of women to cause measurable effects. Folic acid use increased in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom in conjunction with government sponsored education campaigns,17,18 but the long term persistence and effects are unknown. Otherwise, folic acid use in Europe is generally very low—approximately 10% in Norway in 1998,19,20 and 6% in Italy in 2002 (Botto and Bianchi, unpublished data).

What is already known on this topic

Randomised trials showed, more than a decade ago, that folic acid can reduce the occurrence of neural tube defects by half or more

Professional organisations and public health agencies in many countries have tried to promote use of folic acid, either by fortifying foods with folic acid or, more often, by recommending the use of supplements

Studies have shown that fortification of flour can be quickly effective, but the effect of recommendations has not been clearly documented

What this study adds

Recommendations on use of folic acid have had no detectable impact on incidence of neural tube defects, regardless of the recommendations' form, timing, and intended target

In addition to actively promoting the use of supplements, public health agencies and medical professionals should strongly consider implementing food fortification programmes

Whereas any improvement in primary prevention is desirable and should be promoted, a detectable change in the population requires a major shift in the proportion of women consuming adequate amounts of folic acid. It is unclear how successful recommendations alone will be in achieving this goal, given the influence of cultural, social, and economic factors such as the acceptability, availability, and cost of daily supplements. Intensive educational efforts and a very high proportion of planned pregnancies seem to have been crucial factors in the high effectiveness of a public health campaign to promote use of folic acid supplements in areas of China.7 In general, use of supplements tends to follow economic and educational lines,17-19 so targeting the entire population through recommendations on supplementation alone may not be practical.

In this context, fortification of flour represents an additional opportunity to deliver some folic acid to nearly the entire population, across social and economic barriers. Where dietary and food processing conditions are favourable, fortification can be effective quickly and at low cost. In countries that have fortified flour, blood folate concentrations have risen quickly,14,21,22 and although the reductions in incidence were not as large as that achievable through supplementation, such reduction occurred soon after fortification was implemented.12-14

This element of timeliness is crucial. As figure 2 shows, affected pregnancies accumulate for each year that effective prevention is delayed. In the study area, where the yearly births are less than 1% of the estimated 130 million births worldwide, the estimated number of preventable cases that have occurred since 1992 could be in the thousands. This point is mathematically simple but none the less, from a public health perspective, crucial. A reasonable and urgent strategy to reduce this growing and unceasing burden of preventable death and disability is to quickly integrate fortification with a fuller implementation of recommendations on folic acid.

The study was conducted under the auspices of the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM). A Rosano and T Dukic provided technical assistance in the initial phases of the study. The lateRichard (Dick) Smithells was one the leaders of this study, from its conception through planning and initial report writing. We were immensely privileged to work with Professor Smithells, who sadly could not see this study to completion.

Contributors: LDB, ER-G, SEV, PM, JDE, and JG developed the protocol and coordinated the study. JG secured the initial funding, and JG and LDB directed the study. LDB, JG, and SEV developed the analysis, and AL and LDB carried it out. LDB and JG wrote the original draft, worked to secure funding, and directed the study. BB, CdV GC, HdW, MF, LMI, BMcD, PM, AR, GS, CS, JM, and CS generated and provided the data, participated in study development, and contributed to writing the report. LDB is the guarantor.

Funding: European Community (BIOMED Concerted Action PL 96 393 63), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U50/CCU207141).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Participating registries operate under approval of local institutional review boards (IRB), and the joint analysis was done on anonymous data from monitoring systems exempt from IRB approval.

References

- 1.Shibuya K, Murray CJL. Congenital anomalies. In: Murray CJL, Lopez AD, eds. Health dimensions of sex and reproduction. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1998: 455-512.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in infant mortality attributable to birth defects—United States, 1980-1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1998;47: 773-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smithells RW, Sheppard S, Schorah CJ. Vitamin deficiencies and neural tube defects. Arch Dis Child 1976;51: 944-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smithells RW, Sheppard S, Schorah CJ, Seller MJ, Nevin NC, Harris R, et al. Possible prevention of neural-tube defects by periconceptional vitamin supplementation. Lancet 1980;i: 339-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smithells RW, Nevin NC, Seller MJ, Sheppard S, Harris R, Read AP, et al. Further experience of vitamin supplementation for prevention of neural tube defect recurrences. Lancet 1983;i: 1027-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botto LD, Moore CA, Khoury MJ, Erickson JD. Neural-tube defects. N Engl J Med 1999;341: 1509-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry RJ, Li Z, Erickson JD, Li S, Moore CA, Wang H, et al. Prevention of neural-tube defects with folic acid in China: China-U.S. Collaborative Project for Neural Tube Defect Prevention. N Engl J Med 1999;341: 1485-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czeizel AE, Dudas I. Prevention of the first occurrence of neural-tube defects by periconceptional vitamin supplementation. N Engl J Med 1992;327: 1832-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council vitamin study. Lancet 1991;338: 131-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oakley GP. Delaying folic acid fortification of flour. BMJ 2002;324: 1348-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botto LD, Olney RS, Erickson JD. Vitamin supplements and the risk for congenital anomalies other than neural tube defects. Am J Med Genet 2004;125C: 12-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castilla EE, Orioli IM, Lopez-Camelo JS, Dutra Mda G, Nazer-Herrera J. Preliminary data on changes in neural tube defect prevalence rates after folic acid fortification in South America. Am J Med Genet 2003;123A: 123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honein MA, Paulozzi LJ, Mathews TJ, Erickson JD, Wong LY. Impact of folic acid fortification of the US food supply on the occurrence of neural tube defects. JAMA 2001;285: 2981-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray JG, Meier C, Vermeulen MJ, Boss S, Wyatt PR, Cole DE. Association of neural tube defects and folic acid food fortification in Canada. Lancet 2002;360: 2047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosano A, Botto LD, Botting B, Mastroiacovo P. Infant mortality and congenital anomalies from 1950 to 1994: an international perspective [see comments]. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54: 660-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oleary M, Donnell RM, Johnson H. Folic acid and prevention of neural tube defects in 2000 improved awareness—low peri-conceptional uptake. Ir Med J 2001;94: 180-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Walle HE, Cornel MC, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Three years after the Dutch folic acid campaign: growing socioeconomic differences. Prev Med 2002;35: 65-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landon J, Thorpe L. Changing preconceptions: the HEA folic acid campaign 1995-1998. Vol 1 London: Health Education Authority, 1998: 61-2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vollset SE, Lande B. Knowledge and attitudes of folate, and use of dietary supplements among women of reproductive age in Norway 1998. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79: 513-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daltveit AK, Vollset SE, Lande B, Oien H. Changes in knowledge and attitudes of folate, and use of dietary supplements among women of reproductive age in Norway 1998-2000. Scand J Public Health 2004;32: 264-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folate status in women of childbearing age, by race/ethnicity—United States, 1999-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51: 808-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirsch S, de la Maza P, Barrera G, Gattas V, Petermann M, Bunout D. The Chilean flour folic acid fortification program reduces serum homocysteine levels and masks vitamin B-12 deficiency in elderly people. J Nutr 2002;132: 289-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]