Abstract

Background

There is a relative paucity of information on both empirical and subjective treatment strategies for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), especially in late life. This paper reviews the findings from two 2016 surveys conducted through the American Psychiatric Association publication the Psychiatric Times and via a member survey by the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP).

Methods

We present the results of the two surveys in terms of descriptive frequencies and percentages and discuss the strengths and weaknesses of various approaches to late-life TRD.

Results

The Psychiatric Times survey received 468 responses, and the AAGP survey received 117 responses, giving an overall sample of 585 responses. The majority (76.3%) of respondents from both groups believed that a large randomized study comparing the risks and benefits of augmentation and switching strategies for TRD in patients aged 60 years and older would be helpful, and 80% of clinicians believed their practice would benefit from the findings of such a study. Of the treatment strategies that need evidence of efficacy, the most popular options were augmentation/combination strategies, particularly augmentation with aripiprazole (58.7%), bupropion (55.0%), and lithium (50.9%).

Conclusions

Late-life TRD constitutes a large proportion of clinical practices, particularly of geriatric psychiatry, with lacking evidence of efficacy of most treatment strategies. These surveys indicate a clear need for a large randomized study that compares risks and benefits of augmentation and switching strategies.

Keywords: depression, late-life, treatment, survey

Depression is a major public health issue, and is associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and economic burden. It is the third-greatest contributor to global disease burden1 and affects both low- and high-income countries with a 12-month prevalence of 5.9% and 5.5%, respectively.2 Depression is projected to hold the greatest illness burden in high-income countries by 2030,1 and it is therefore paramount to develop a coordinated strategy for its treatment. The economic cost of depression in the United States is estimated to be $210.5 billion, with 45% attributable to direct medical costs, 5% to suicide-related costs, and 50% to indirect workplace costs (i.e., loss of productivity through absenteeism and presenteeism3).

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) is defined as failure to achieve disease remission with adequate trials of two or more pharmacologically dissimilar antidepressants, and accounts for 12%–20% of depression cases.4,5 It is believed to arise from biological incompatibility between the molecular basis of an individual's depression and the antidepressant used to treat it, and/ or due to a comorbidity hindering antidepressant effect, such as psychiatric co-morbidity, childhood trauma, or personality disorder.6 Fewer than 55% of patients achieve remission with first and second trial of antidepressants, meaning a significant portion of depression does not respond to conventional treatment guidelines.7

There is a relative paucity of information on treatment options and efficacy in TRD, especially in late life. This paper reviews the findings of a clinician survey on TRD, conducted by the Psychiatric Times and the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP), and discusses both strengths and weaknesses of various approaches to TRD.

Methods

A brief online survey on clinician attitudes towards TRD was composed by the OPTIMUM co-investigators and edited by the editors of the Psychiatric Times and the AAGP research committee. Both surveys used identical questions. The surveys were both conducted in January 2016. The Psychiatric Times distributed the survey through an e-blast to 100,000 Web subscribers. A notification of the survey was also in the printed journal, which has a subscribership of 40,000. The AAGP distributed the survey through an e-mail to 1,355 subscribers. The survey sought information about practice location, work setting, years in practice; proportion of treatment-resistant patients in practice, including those 60 years and older; and the need to acquire evidence of efficacy for a variety of augmentation or switching strategies was obtained from both groups of clinicians. Half of the questions had set answers to choose from, and half were free-text. Data were pooled from both surveys unless otherwise stated.

Results

The Psychiatric Times survey received 468 responses (0.47% response rate), and the AAGP survey received 117 responses (8.63% response rate); the overall sample size was 585. Those participating in the surveys represented a variety of clinical backgrounds and work settings, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Respondent Field of Practice or Work Setting.

| Psychiatric Times | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Primary Field of Practice | % Responses (N = 465) |

| General psychiatry | 45.8 |

| Child psychiatry | 1.9 |

| Geriatric psychiatry | 3.9 |

| Psychology | 7.7 |

| Other mental health professional | 14.0 |

| Student / Resident | 4.3 |

| Other (please specify) | 22.4 |

|

| |

| AAGP | |

|

| |

| Work Setting | % Responses (N = 110) |

|

| |

| Individual clinical practice | 25.5 |

| Healthcare system | 49.1 |

| Academic | 57.3 |

| Teaching | 32.7 |

| Individual clinical practice | 25.5 |

The United States was well represented in the surveys, contributing 80.1% of responses from across the Northeast (26.1%), Southeast (16.7%), Midwest (18.1%), Southwest (7.5%) and West (12.5%) regions of the country. The remaining 19.1% of responses came from 41 countries, including Australia, the UK, Canada, and India. Both sides of the experience spectrum were represented, with 33.8% of respondents in their first decade of practice, and 35.8% having practiced for more than 25 years. The balance of genders was marginally in favor of female respondents. The respondent demographics are broken down further in Table 2.

Table 2. Respondent Demographics.

| Psychiatric Times, N | AAGP, N | Aggregate (N, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years in practice | |||

| 0–5 | 102 | 26 | 128 (22.2%) |

| 6–10 | 53 | 14 | 67 (11.6%) |

| 11–15 | 48 | 10 | 58 (10.1%) |

| 16–20 | 49 | 15 | 64 (11.1%) |

| 21–25 | 40 | 13 | 53 (9.2%) |

| 25 + | 167 | 39 | 206 (35.8%) |

| N = 459 | N = 117 | Total N = 576 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 206 | 62 | 268 (47.4%) |

| Female | 243 | 54 | 297 (52.6%) |

| N = 449 | N = 116 | Total N = 565 | |

| Location | |||

| Northeast | 115 | 35 | 150 (26.1%) |

| Southeast | 74 | 22 | 96 (16.7%) |

| Midwest | 79 | 25 | 104 (18.1%) |

| Southwest | 37 | 6 | 43 (7.5%) |

| West | 58 | 14 | 72 (12.5%) |

| Outside of United States | 95 | 15 | 110 (19.1%) |

| N = 458 | N = 117 | Total N = 575 | |

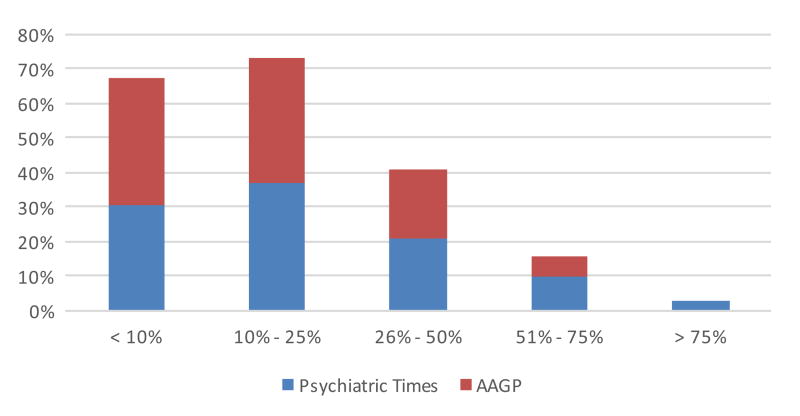

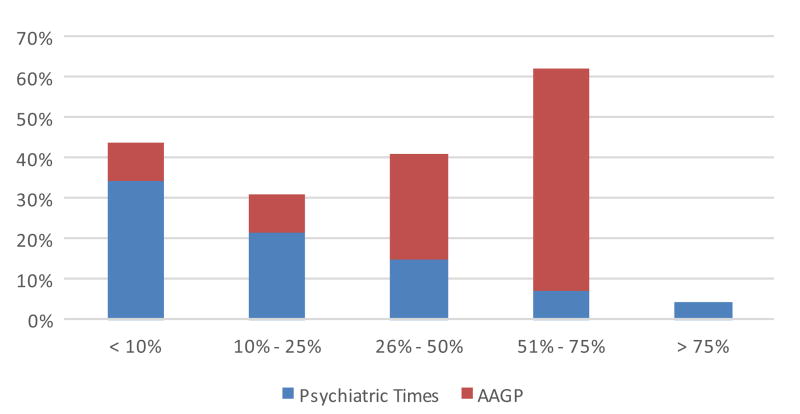

Two-thirds of respondents reported that TRD accounted for up to one-quarter of their practice, and an additional 20.8% reported that it accounted for up to one-half of their practice (Table 3). Patients aged 60 years or over accounted for 10%–25% of the TRD workload in 32% of practices, and this was the mode response. General psychiatrists responding to the Psychiatric Times survey responses indicated a lower proportion of older TRD patients in their practices compared with the AAGP survey responses, indicating that geriatric psychiatrists carry the heaviest load of treating these patients. The aggregate results are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 3. TRD Prevalence and Patient Age Demographics.

| Psychiatric Times, N | AAGP, N | Aggregate (N, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % patients with TRD | |||

| <10% | 136 | 43 | 179 (31.6%) |

| 10%–25% | 166 | 42 | 208 (36.7%) |

| 26%–50% | 95 | 23 | 118 (20.8%) |

| 51%–75% | 43 | 7 | 50 (8.8%) |

| >75% | 11 | a | 11 (1.9%) |

| N = 451 | N = 115 | Total N = 566 | |

| % TRD patients aged | |||

| 60 + years | |||

| <10% | 187 | 9 | 196 (26.5%) |

| 10%–25% | 118 | 9 | 127 (32.0%) |

| 26%–50% | 82 | 25 | 107 (21.9%) |

| 51%–75% | 39 | 53 | 92 (17.6%) |

| >75% | 25 | a | 25 (2.0%) |

| N = 547 | N = 96 | Total N = 547 | |

Note:

Not an answer option in this survey.

Figure 1. TRD workload as a percentage of total practice.

Figure 2. TRDOA workload as a percentage of TRD practice.

The majority (76.3%) of respondents in both groups believe that a large randomized study comparing the risks and benefits of augmentation and switching strategies for TRD in patients aged 60 years and older would be helpful, of which more than one-third would find it extremely helpful, as outlined in Table 4. Importantly, four in five clinicians believe that their practice would benefit from the findings of such a study.

Table 4. Respondent Views on Large Randomized Study Comparing Augmentation and Switching Strategies for TRD patients Aged 60 + Years.

| Psychiatric Times | AAGP | Aggregate (N, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived helpfulness rating | |||

| 1 (Not helpful) | 17 | 93 | 110 (19.2%) |

| 2 | 26 | a | 26 (4.5%) |

| 3 (Helpful) | 86 | 22 | 108 (18.8%) |

| 4 | 127 | a | 127 (22.2%) |

| 5 (Very helpful) | 201 | 1 | 202 (35.3%) |

| N = 457 | N = 116 | Total N = 573 | |

| Preferred treatments to be studied | |||

| Augmentation with aripiprazole | 240 | 91 | 331 (58.7%) |

| Augmentation with bupropion | 222 | 88 | 310 (55.0%) |

| Augmentation with lithium | 204 | 83 | 287 (50.9%) |

| Switching to bupropion | 128 | 46 | 174 (30.9%) |

| Switching to nortriptyline | 128 | 56 | 184 (32.6%) |

| Other (please specify) | 159 | a | 159 (28.2%) |

| N = 451 | N = 113 | Total N = 564 | |

| Perceived to benefit clinician's practice | |||

| Yes | 347 | 106 | 453 (79.9%) |

| No | 28 | 0 | 28 (4.9%) |

| Not sure | 78 | 8 | 86 (15.2%) |

| N = 453 | N = 114 | Total N = 567 |

Note:

Not an answer option in this survey.

When offered a choice of treatments to be studied, the most popular options were augmentation strategies—namely, augmentation with aripiprazole (58.7%), bupropion (55.0%), and lithium (50.9%). Switching to bupropion and nortriptyline were less popular, as seen in Table 4.

The Psychiatric Times offered respondents an opportunity to suggest an alternative treatment to be studied, and just less than one-third of survey takers took this opportunity. The most common suggestions were psychotherapy, augmentation with antipsychotics, transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep brain stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, addition of a second antidepressant both typical (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], tricyclic antidepressants, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors) and atypical (mirtazapine) as well as newer agents (vortioxetine), use of methylphenidate and other stimulants, ketamine, and lamotrigine. Several respondents suggested supplementation of thyroid hormone, and less frequently, folate and omega 3. Other drugs named were memantine, pramipexole, pindolol, nefazodone, buspirone, and glutaminergic treatment. Finally, lifestyle measures such as exercise and various complementary and alternative practices, including acupuncture, were also suggested.

Discussion

The findings of this survey support reported rates of TRD of 10%–25% in community samples. In older adults, depression is more likely to follow a chronic or relapsing course,8 and 55%–81% of older adults with major depressive disorder fail to respond to an SSRI or SNRI.9 Depression in older age is an important risk factor for all-cause dementia,10 and is associated with higher utilization of health care services, caregiver burden, and suicide rates.11,12

The findings of our survey support TRD being a significant unresolved issue in practices of general and geriatric psychiatrists. Previous studies, including STAR*D, VAST-D, PReDICT and iSPOT-D, have explored treatment of TRD in young adults, yet there is a relative paucity of research in the management of TRD in older adults (also known as TRDOA).13 Global aging of the population brings this undertreated population to the forefront of the attention of both clinicians and researchers. This view is shared by 76.3% of our survey respondents.

In general TRD populations, a meta-analysis reviewing 48 trials of augmentation agents found that quetiapine, aripiprazole, thyroid hormone, and lithium were significantly more effective than placebo in treatment, notwithstanding tolerability issues with antipsychotics and lithium, and safety issues with thyroid hormone supplementation.14 In TRDOA, a double-blind randomized control trial of aripiprazole to augment venlafaxine therapy achieved 12 weeks of sustained remission in almost half the participants assigned to the intervention group, with a number needed to treat of 6.6.9 The use of aripiprazole in older adults was associated with mild and transient akathisia and Parkinsonism, typically tremor, but not associated with cardiometabolic side effects, QTc prolongation, or increased suicidal ideation.9 In this same study, severe baseline anxiety and cognitive inflexibility were associated with reduced remission rates.15 These findings demonstrate that aripiprazole has good outcomes, tolerability, and safety in TRDOA.

Conclusions

TRD is clearly a major burden to communities and health services. In the general adult population, there are a number of promising treatment strategies for TRD in development including ketamine, novel compounds, somatic treatments and brain stimulation treatment options, complementary and integrative treatment modalities, and pharmacogenetics guidance. There is a clear need for more randomized studies that explore novel treatments, and compare risks and benefits of different combination strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help of Eric Lenze, M.D., Benoit Mulsant, M.D., Steven Roose, M.D., and Charles F. Reynolds, M.D.—collaborators on the “OPTIMUM” study of optimizing treatment strategies for late-life geriatric depression that generated questions for the TRD survey.

Footnotes

The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Katarina Arandjelovic, IMPACT Strategic Research Centre, School of Medicine, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, Australia

Harris A. Eyre, IMPACT Strategic Research Centre, School of Medicine, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, Australia; Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behaviour, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Discipline of Psychiatry, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Helen Lavretsky, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behaviour, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

References

- 1.Cuijpers P, Beekman ATF, Reynolds CF. Preventing depression: a global priority. JAMA. 2012;307:1033–1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Ann Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010) J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:155–162. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntyre RS, Filteau MJ, Martin L, et al. Treatment-resistant depression: definitions, review of the evidence,and algorithmic approach. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mrazek DA, Hornberger JC, Altar CA, et al. A review of the clinical, economic,and societal burden of treatment-resistant depression: 1996–2013. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:977–987. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huynh NN, McIntyre RS. What are the implications of the STAR*D trial for primary care? A review and synthesis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10:91–96. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v10n0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Licht-Strunk E, Beekman AT, de Haan M, et al. The prognosis of undetected depression in older general practice patients. A one year follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Blumberger DM, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of augmentation pharmacotherapy with aripiprazole for treatment-resistant depression in late life: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2404–2412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00308-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, et al. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:329–335. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unutzer J, Park M. Older adults with severe, treatment-resistant depression. JAMA. 2012;308:909–918. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Consensus statement update. JAMA. 1997;278:1186–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper C, Katona C, Lyketsos K, et al. A systematic review of treatments for refractory depression in older people. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:681–688. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X, Ravindran AV, Qin B, et al. Comparative efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of augmentation agents in treatment-resistant depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:e487–e498. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14r09204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaneriya SH, Robbins-Welty GA, Smagula SF, et al. Predictors and moderators of remission with aripiprazole augmentation in treatment-resistant late-life depression: an analysis of the IRL-GRey randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:329–336. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]