Abstract

Background

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia (ARVC/D) is an inherited cardiomyopathy mainly caused by heterozygous desmosomal gene mutations, the major gene being PKP2. The genetic cause remains unknown in ~50% of probands with routine desmosomal gene screening. The aim of this study was to assess the diagnostic accuracy of whole exome sequencing (WES) in ARVC/D with negative genetic testing.

Methods

WES was performed in 22 patients, all without a mutation identified in desmosomal genes. Putative pathogenic variants were screened in 96 candidate genes associated with other cardiomyopathies/channelopathies. The sequencing coverage depth of PKP2, DSP, DSG2, DSC2, JUP and TMEM43 exons was compared to the mean coverage distribution to detect large insertions/deletions. All suspected deletions were verified by real-time qPCR, Multiplex-Ligation-dependent-Probe-Amplification (MLPA) and cGH-Array. MLPA was performed in 50 additional gene-negative probands.

Results

Coverage-depth analysis from the 22 WES data identified two large heterozygous PKP2 deletions: one from exon 1 to 14 and one restricted to exon 4, confirmed by qPCR and MLPA. MLPA identified 2 additional PKP2 deletions (exon 1–7 and exon 1–14) in 50 additional probands confirming a significant frequency of large PKP2 deletions (5.7%) in gene-negative ARVC/D. Putative pathogenic heterozygous variants in EYA4, RBM20, PSEN1, and COX15 were identified in 4 unrelated probands.

Conclusion

A rather high frequency (5.7%) of large PKP2 deletions, undetectable by Sanger sequencing, was detected as the cause of ARVC/D. Coverage-depth analysis through next-generation sequencing appears accurate to detect large deletions at the same time than conventional putative mutations in desmosomal and cardiomyopathy-associated genes.

Introduction

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia (ARVC/D) is mainly caused by heterozygous mutations in genes encoding the main cardiac desmosome components (so-called desmosomal genes hereafter): PKP2, which is the major gene, DSP, JUP, DSG2 and DSC2 [1,2]. Other non desmosomal genes such as TMEM43, RYR2, LMNA, PLN or DES have been associated with atypical or typical forms of ARVC/D, suggesting genetic and clinical overlaps with dilated cardiomyopathy or catecholergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. International Task Force criteria, on which ARVC/D diagnosis is currently based, lack sensitivity in early phase of the disease [3,4]. However, the risk of sudden cardiac death is present throughout all stages, including the early phase. Predictive genetic testing is thus highly important to set-up cardiac follow-up and preventive strategies such as sport restriction in relatives at risk [5]. However, in families with negative genetic screening, identification of relatives at risk remains difficult, as ARVC/D diagnosis remains highly challenging due to a broad clinical spectrum of the disease and age- and gender-dependent penetrance.

Until recently, routine molecular screening of ARVC/D probands was usually performed using Sanger sequencing or High Resolution Melt (HRM) detection of desmosomal genes coding sequences. This approach allows the detection of the genetic cause in only ~50% of cases [6]. Several factors can explain negative genetic screening: (a) desmosomal mutations undetected by Sanger sequencing such as large PKP2 deletions [7,8] (b) phenotype misclassification[9], (c) mutations in genes not known as causal in ARVC/D [10–14].

We hypothesized that next generation sequencing (NGS) represented in this study by whole exome sequencing (WES), could improve genetic diagnosis of ARVC/D by allowing the detection of new genetic causes or mechanisms for this rare cardiomyopathy. We focused our analysis on the detection of large deletions in desmosomal genes hardly detected by conventional Sanger sequencing, and on putative mutations in a large panel of genes associated with other inherited cardiomyopathies and arrhythmias.

Material and methods

Patient selection and clinical data

ARVC/D diagnosis was made according to Task Force criteria by a multidisciplinary consensus expert team [3]. We selected for WES: patients above 18 years with a diagnosis of familial ARVC/D (at least one affected first degree relative) or histologically proven ARVC/D and with no disease-causing mutations in known desmosomal genes (PKP2, DSG2, DSP, DSC2, JUP) with standard Sanger sequencing at the time of the study. One proband carried a variant of unknown significance in DSG2 (p.Thr335Ala variant at homozygous state) and two others carried a rare benign polymorphism (DSP p.Gly2568Ser and DSC2 p.Gly790del). All patients gave their informed consent for genetic study and research purposes; the study was performed according to the declaration of Helsinski and was approved by local ethics committee, the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital ethical committee. Overall, WES was performed in 23 subjects: 16 index cases with familial history of ARVC/D, one family with 3 affected family members and a healthy relative used as internal control and 3 sporadic cases with severe ARVC/D. We secondarily selected 50 additional ARVC/D unrelated probands with previous negative genetic testing for Multiplex-Ligation-dependent-Probe-Amplification (MLPA) analysis. We collected the following clinical data for each patients and available relatives: symptoms, 12-leads ECG, signal averaged-ECG, 24h-Holter monitoring, exercise test, cardiac imaging (echocardiography, cardiac MRI and contrast angiography), histology when available and familial history.

Exome sequencing and coverage depth analysis (details in S1 Methods)

WES was performed by targeted capture using the “Agilent SureSelect All Exon v5 50Mb kit” and 75 bases paired-end sequencing with Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Integragen). Copy number variation (CNV) was analyzed using the DNACopy (Bioconductor) package furnished by Integragen. The coverage depth of each exon of PKP2, DSG2, DSP, JUP and DSC2 was analyzed on 25 base pairs windows with the IGV software (https://www.broadinstitute.org/igv). The depth of coverage distribution for each exon, reflecting copy number of genomic targets, was normalized to the mean coverage in the whole cohort (23 patients). Heterozygous deletion was suspected if normalized coverage was less than one standard deviation (SD) of the mean coverage distribution for the whole cohort.

Cardiomyopathy panel description

All the genes known to be associated with inherited cardiomyopathies were selected (detail in S2 Method). We selected rare variants with depth coverage > 10 and a minor allelic frequency (MAF) < 0.05% in the control databases 1000 genomes (http://1000genomes.org) and EXAC (http://exac.broadinstitute.org). Rare variants were considered as putative mutations in case of (a) radical mutations (nonsense, ins/del, splice-site); (b) missense mutations predicted as disease-causing by at least 4 over 5 prediction softwares (Polyphen-2, SIFT, Mutation Taster,mutation assessor and CADD score > 20). Criteria for classifying variants as pathogenic or benign were assessed for each variant according to the ACMG standards and guidelines [15]. Variants classified as pathogenic by 4 over 5 prediction softwares were classified PP3, otherwise they were classified BP4. Variants absent in control databases EXAC and 1000 genomes were classified PM2. Variants with a MAF >0.015% in EXAC (which corresponds to the higher frequency of PKP2 disease-causing mutations in EXAC) were classified BS1. In silico analysis were performed using the wANNOVAR tool (http://wannovar.usc.edu).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assays using primers specific for the PKP2 exons 1, 3, 4, 5 and 13 were performed to validate large deletions (details in S1 Table).

MLPA, microarray and targeted capture sequencing

MLPA was performed using the SALSA MLPA168 ARVC-PKP2 commercial kit from MRC-Holland® on an ABI-Prism 3130. The microarray was performed with a HumanOmniExpress-24v1.0 chip (Illumina) and analysed with the Illumina GenomeStudio V2011.1 software. Targeted Capture sequencing of PKP2 was performed with the Trusight Cardiomyopathy sequencing panel (Illumina) on a Miseq (Illumina).

Immunofluorescence study

Heart tissues samples (right and left ventricles, directly frozen in isopentane) were collected from the proband U.1 explanted heart, as described previously [16]. Patient gave his informed consent for the use of tissue samples for research purpose. Five μm sections were fixed in paraformaldehyde/ cold methanol (-20°C) and co-imuno-labelled with primary antibodies anti-PKP2 (PKP2-518, Progen, 1/4). Monolayers were directly visualized by fluorescent microscopy with an Olympus IX50 microscope and 3D deconvolution was performed using the Metamorph software (Roper Scientific).

Results

WES coverage depth analysis

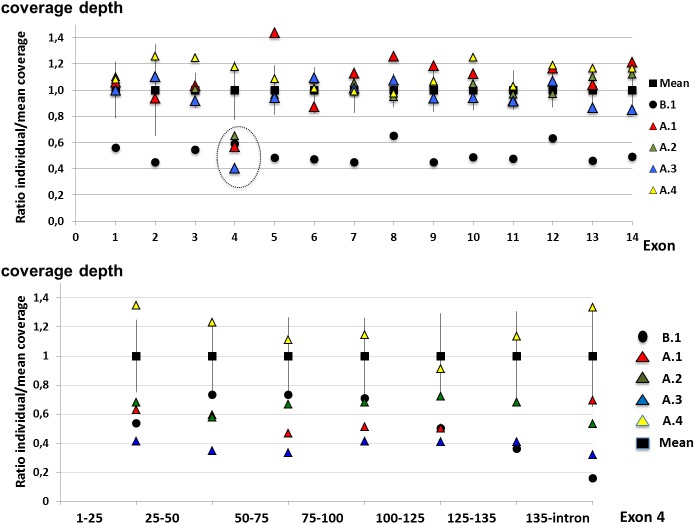

Summary of WES run including average coverage per sample and remarkable values (number of missense variant, non-sense variant and Indel present with a frequency less than 0,1% of the control cohort) are represented in S2 Table. For all patients, the exome coverage depth percentage of at least 10 reads were above 95%.The coverage depth of PKP2 exons was > 35 reads for all exons except exon 1 and 2 that displayed a low coverage depth (9.7±2.1 and 3.0±1.1 reads respectively, S3 Table). Normalized coverage distribution analysis showed low coverage under one SD for all PKP2 exons in individual B.1 (45 to 65% of the mean coverage value) suggesting whole PKP2 heterozygous deletion. In family A, we observed a low coverage of exon 4 in the three affected subjects (A.1, A.2 and A.3, from 41 to 65% of the mean coverage value) suggestive of deletion restricted to exon 4 (Fig 1). Exon 4 coverage depth of the healthy relative (individual A.4) was within SD values (118%). Coverage depth analysis of JUP, DSC2, DSP, DSG2 and TMEM43 did not identify CNV in these genes.

Fig 1.

PKP2 exons coverage depth analysis from WES in individuals from family A and B.1. The coverage depth of all PK2 exons was under standard deviation of the mean coverage in individual B1 indicating a probable deletion of the whole PKP2 gene. Coverage depth analysis showed a coverage reduction restricted to exon 4 in affected individuals from family A (dashed circle).

MLPA, qPCR and cGH-Array analysis

Our rate of detection of large deletion in PKP2 using NGS coverage was close to 10%. In order to confirm this finding and to better assess this frequency we performed MLPA in the 20 initial probands and in 50 additional unrelated ARVC/D probands with negative genetic screening in desmosomal genes. MLPA confirmed the heterozygous deletion restricted to exon 4 in family A and the heterozygous whole PKP2 deletion in patient B.1. Furthermore, we identified by MLPA a complete PKP2 deletion in two additional probands (U.1 and V.1). Overall, the frequency of large PKP2 deletions was 5.7% (4/70) in ARVC/D with initial negative screening. No large deletions were detected in JUP, DSG2, DSC2, DSP or TMEM43 by MLPA, as observed by WES.

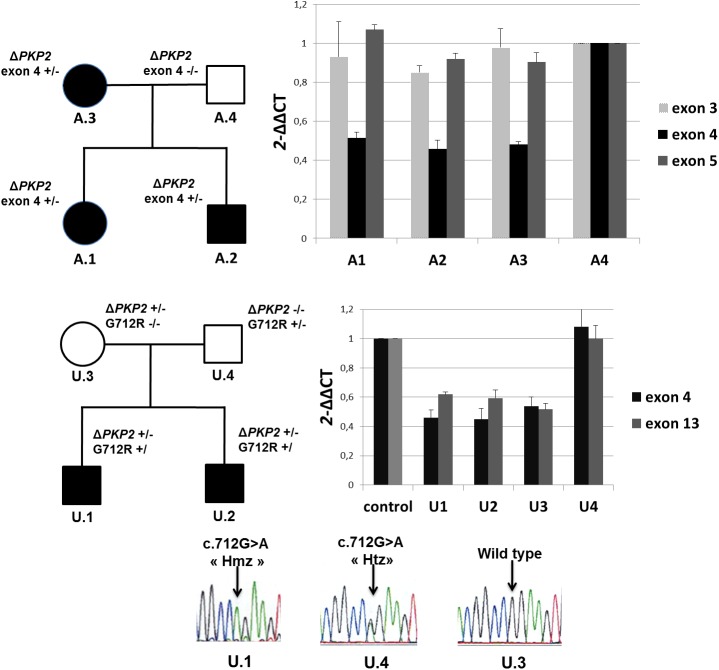

All PKP2 deletions identified through coverage depth analysis and MLPA were confirmed using qPCR. The relative copy number of PKP2 exon 4 was about 0.5 in all affected individuals from family A compared with the healthy control but the relative copy numbers of exon 3 and 5 were about 1. This confirmed the presence of the heterozygous deletion of exon 4 that cosegregated with the phenotype in the family (Fig 2 and S4 Table). In families B and U, real-time qPCR indicated a relative copy number of about 0.5 for PKP2 exon 3, 4 and 13 in affected probands and relatives compared with the control sample, confirming the large heterozygous PKP2 deletion (Fig 2 and S5 Table). In both families, the large deletion was inherited from the asymptomatic mother who has no ARVC criteria of diagnosis on cardiac evaluation, and present in the affected brother (Table 1).

Fig 2. Pedigree and qPCR results from family A and U.

qPCR showed a ~50% reduction of exon 4 PKP2 DNA in affected individuals A.1, A.2 and A3 compared to the healthy father A.4 (used as a control). PKP2 DNA quantification was normal in exon 3 and 5 for all individuals. In family U, qPCR showed a 50% reduction of PKP2 DNA in exon 4 and 13 in affected individuals U.1 and U.2 and their mother U.3 whereas it was comparable to controls in father U.4. Individuals U.1 and U.2 also carried the p.Gly712Arg (G712R) rare PKP2 variant that falsely appeared in the Sanger chromatogram as homozygous (HmZ) instead of hemizygous because of the absence of the other PKP2 allele. This variant was inherited from the father, in absence of familial history of consanguinity, in whom it appeared heterozygous(Htz).

Table 1. Clinical data of probands and relatives carrying a large PKP2 heterozygous deletion.

| Family |

Patient |

Familial status | Sex | Age at diagnosis | Family history | TWI | Epsilon waves | SA-ECG | Arrhythmia | RV | LV | TF criteria | Clinical status | Deletion | Deletion bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | Proband | F | 29 | SCD gd-father at 30 (min) | V1-V3 (Maj) | abs | abs | RVOT VT (min) | Maj | abs | 2Maj/2min | Affected | Exon 4 | Arr[hg19] 12p11.21 [32,979,318–33,062,23]x1 |

| 2 | Brother | M | 21 | Maj | V1-V3 (Maj) | abs | abs | abs | Maj | abs | 3Maj | Affected | Exon 4 | ||

| 3 | Mother | F | 52 | Maj | V1-V3 (Maj) | abs | abs | >500 PVC (min) | min | abs | 2Maj/2min | Affected | Exon 4 | ||

| B | 1 | Brother | M | 37 | Maj | abs | Maj | + | RVOT VT (min) | Maj | abs | 3Maj/1min | Affected | Exon 2–14 | Arr[hg19] 12p11.21 [32,943,679–33,049,780]x1 |

| 2 | Proband | M | 45 | abs | V1-V3 (Maj) | Maj | + | >500 PVC (min) | Maj | abs | 3Maj/1min | Affected | Exon 2–14 | ||

| 3 | Mother | F | 73 | Maj | V1-V3 (Maj) | abs | abs | NSVT (min) | Maj | abs | 3Maj/1min | Affected | Exon 2–14 | ||

| U | 1 | Proband | M | 17 | abs | V1-V6 (Maj) | Maj | + | SCD, Sustained VT (min) | Maj | + | 3Maj/1min | Affected | Exon 1–14 + PKP2 G712R | Arr[hg19] 12p11.21 [32,935,752–33,064,825]x1 |

| 2 | Brother | M | 23 | Maj | abs | Maj | abs | abs | abs | abs | 2Maj | Affected | Exon 1–14 + PKP2 G712R |

||

| 3 | Mother | F | Maj | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Exon 1–14 | |||

| V | 1 | Proband | M | 22 | abs | V1-V3 (Maj) | abs | abs | Sustained VT (min) | min | abs | 1Maj/2min | Affected | Exon 1–7 | Arr[hg19] 12p11.21 [32,979,318–33,062,23]x1 |

M: male; F: female; Maj/min/abs: major/minor/absent criterion of the International 2010 ARVC Task Force; TF criteria: task force criteria; TWI: T wave inversion; SAECG: signal-average ECG; RVOT VT: ventricular tachycardia from right ventricular outflow tract; PVC: premature ventricular complex; RV: right ventricle; LV dys: left ventricle dysfunction; SCD: sudden-cardiac-death; NSVT: non-sustained VT; NA: non-available data. Deletions bonds are given according to the ISCN 2013 guidelines (ref GRCh37/hg19).

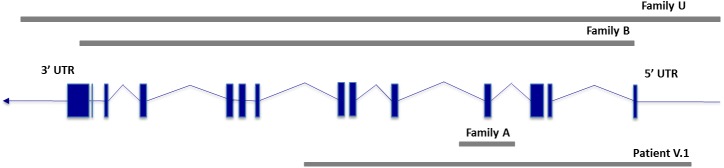

The microarray analysis confirmed the three complete PKP2 deletions in individuals B.1, U.1 and V.1 (details in Table 1 and Fig 3) but lacked sensitivity to detect the deletion restricted to exon 4 in proband A.1 due to a unique informative SNP of this exon (which had a negative log ratio).

Fig 3. Schematic view of PKP2 deletions.

Targeted capture and subsequent NGS of PKP2 exons was performed in patient U.1 confirming a 50% coverage reduction for all exons (S1 Fig).

Clinical data of PKP2 large deletion carriers

Phenotype of individuals carrying a large PKP2 deletion is provided in Table 1. All of them displayed a definite ARVC/D diagnosis. Patient U.1 developed severe ARVC/D with bi-ventricular involvement and heart failure leading to heart transplantation. This patient was a compound heterozygous for the large PKP2 deletion (inherited from his mother) and the rare PKP2 p.Gly712Arg variant of unknown pathogenicity (allele frequency 0.0024%) inherited from his father in absence of familial history of consanguinity, which therefore appeared as “homozygous” instead of hemizygous in Sanger sequencing (Fig 2). The Mutation Taster and Polyphen-2 prediction software classified this rare variant as deleterious, however with probable incomplete penetrance in a heterozygous context. The immunofluorescence staining of PKP2 in cardiac tissue from the proband U.1 explanted heart showed normal PKP2 location at intercalated disks (S2 Fig).

Cardiomyopathy associated genes analysis

96 genes previously associated with various cardiomyopathies/channelopathies were screened for putative mutation. 41 rare variants with MAF< 0.05% were present in 20 different genes (ANK2, CACNB2, COX15, DSP, EYA4, FLNC, KCNE1, KCNH2, KCNJ5, KCNQ1, MYBPC3, MYH6, MYLK2, MYOM1, NEXN, PSEN1, RBM20, SCN1B, SOS1, TTN) (see S6 Table—Rare cardiomyopathy variants with AGMG score). However, only 4 heterozygous rare genetic variants met at least one or two criteria for pathogenicity without benign criteria:: p.Arg356Gly in EYA4; p.Arg761Gln in RBM20, p.Tyr189Cys in PSEN1, p.Gly174Ser in COX15 which were identified in four unrelated probands. The clinical data and the detailed list of putative mutations are available in Tables 2 and 3. None of these patients displayed an extra-cardiac involvement. The EYA4 and RBM20 variants were also present in the affected father of the proband. The COX15 variant did not segregate with the disease within the family and was therefore unlikely to be disease causing. No segregation data were available for the PSEN1 variant. The EYA4, PSEN1 and RBM20 variants are classified as variants of uncertain significance according to the ACMG guidelines in absence of large familial segregation study or functional study.

Table 2. Clinical data of probands carrying putative pathogenic mutations.

| Patient |

Familial status | Sex | Age at diagnosis | Family history | TWI | Epsilon waves | SA-ECG | Arrhythmia | RV | LV dys |

TF criteria | Clinical status | Suspected gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QT4286 | Proband | F | 17 | abs | V1-V5 (Maj) | abs | + (min) | > 500 PVC (min) | Maj | abs | 2Maj/ 1min |

Affected | EYA4 |

| QT7052 | Proband | F | 21 | abs0 | V1-V4 (Maj) | abs | abs | NSVT (min) | Maj | abs | 2Maj/ 1min |

Affected | RBM20 |

| 1–46767 | Proband | M | 34 | + (min) | 0 | abs | + (min) | NSVT (min) | Borderline | abs | 3min | Borderline | COX15 |

| QT4029 | Proband | M | 46 | abs | V1-V4 (Maj) | abs | + (min) | Sustained VT (Maj) | Maj | abs | 3Maj/ 1min |

Affected | PSEN1 |

M: male; F: female; Maj/min/abs: major/minor/absent criterion of the International 2010 ARVC Task Force; TF criteria: task force criteria; TWI: T wave inversion; SAECG: signal-average ECG; RVOT VT: ventricular tachycardia from right ventricular outflow tract; PVC: premature ventricular complex; RV: right ventricle; LV dys: left ventricle dysfunction; SCD: sudden-cardiac-death; NSVT: non-sustained VT; NA: non-available data.

Table 3. Detailed list and characteristics of putative mutations.

| Patient | Origin | Gene | Protein (c.DNA) | Allele | 1000 Genome MAF | ExAC MAF | SIFT | Polyp- 2 |

Mutation Taster |

Mutation Assessor | CADD score | Segregation | ACMG criteria | Literature-reported associated phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QT4286 | Caribbean | EYA4 (NM_172105) | p.Arg356Gln (c.1085G>A) rs762144530 |

HtZ | absent | 0.002% (absent*) | D | D | D | M | 36 | Yes (affected father) | PP3, PP1 | Dominant DCM and hearing loss[17] |

| QT7052 | Caucasian | RBM20 (NM_001134363) | p.Arg761Qln (c.2282G>A) rs556897484 |

HtZ | 0.020% | 0.005% | D | D | D | L | 22.5 | Yes (affected father) | PP3, PP1 | Dominant DCM[18–19] |

| 1–46767 | Caucasian | COX15 (NM_004376) | p.Gly174Ser (c.520G>A) rs763842058 |

HtZ | absent | 0.005% | D | D | D | H | 36 | no | PP3, BS4 | Recessive Leigh Syndrome/cardio-encephalopathy |

| QT4029 | Caribbean | PSEN1 (NM_000021) | p.Tyr189Cys (c.566A>G) rs556147068 |

HtZ | 0.020% | 0.002% (0.01%*) | D | D | D | M | 21.3 | NA | PP3 | Dominant DCM [20] |

SIFT: D: damaging, T: tolerant; Polyphen-2: D: damaging, P: polymorphism; Mutation taster: D: damaging; Mutation Assessor: probability of pathogenic mutation: L: low, M: medium, H: High. DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; RCM: restrictive cardiomyopathy, HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. HmZ: homozygous; HtZ: heterozygous. MAF: minor allele frequency. NA: not available.

*: EXAC MAF in African population.

CNV in cardiomyopathy genes were also screened (results in S7 Table). Putative large deletion of NEXN and SDHA and duplication of ACTA1 were identified in family A where a PKP2 large deletion was also found. These CNVs did not segregate with the disease within the family and were therefore considered as polymorphisms. A duplication of TNNT2 was also identified in one proband but was considered as a probable polymorphism because of the high frequency of TNNT2 duplication in control databases (S7 Table). A putative large deletion of ABCC9 was identified in one proband and was considered of unknown significance because of its low frequency in controls.

Discussion

This study reports for the first time the identification of large PKP2 deletions through coverage depth analysis and the added value of WES for genetic diagnosis in ARVC/D.

Accuracy of WES for detection of large PKP2 deletions

WES data can be used to check large CNVs in ARVC/D patients with no disease-causing mutations in known desmosomal genes. WES allowed the diagnosis of large PKP2 deletions in two independent probands. These deletions were undetected by standard Sanger sequencing. Overall, we observed a 5.7% frequency of large deletions in ARVC/D with previous negative genotyping in desmosomal genes. This frequency is higher than previously reported, as frequency of large deletions ranged between undetected in a Danish cohort and 2 to 3% in a Dutch cohorts [21,22]. However, the higher PKP2 deletion frequency observed in our study is probably linked to the selective inclusion of cases with no detected mutation after a standard primary mutation screening. Phenotypes associated with large PKP2 deletions in our cohort were typical ARVC/D phenotypes and all fulfilled International task force diagnosis for ARVC/D. The sole patient with a severe phenotype also carried a hemizygous rare missense PKP2 variant (p.Gly712Arg) possibly worsening the expression of the disease. This hypothesis is supported by previous studies showing the modifying role of rare PKP2 missense variants [23,24]. Such variants would have little effect in the presence of a normal allele but express its pathogenicity in a hemizygous context. Due to the associated heterozygous large PKP2 deletion, the rare missense variant appeared as “homozygous” by Sanger sequencing. Therefore, the identification of such rare homozygous variants in routine sequencing should raise suspicion for an underlying large deletion of the other allele.

Our results suggest that large PKP2 mutations are a significant cause of ARVC/D undetected by routine Sanger sequencing worthy to be screened in routine molecular diagnosis. NGS presents a better cost/effectiveness ratio and progressively substitutes to Sanger sequencing for routine molecular screening of inherited cardiomyopathies. Our study shows that the coverage depth analysis of NGS appears effective to detect large PKP2 mutations, including those restricted to a single exon as in family A. A careful analysis is however necessary to detect single exon deletions. All suspected deletions were confirmed by qPCR and MLPA, demonstrating the sensitivity of this method. However, coverages of exon 1 and 2 in WES were particularly low (< 10 reads) due to GC-rich contents. Lack of sensitivity of WES to detect early exons deletions in PKP2 due to low coverage of these exons might be circumvent using targeted capture based resequencing as strongly suggested by the high coverage (169 to 325 reads) observed when it was applied to U.1 patient’s DNA (S1 Fig). Although no insertion CNV was identified by coverage depth analysis in desmosomal genes, we cannot exclude that the mean coverage values obtained by WES preclude accurate detection of these variations. The microarray method is highly accurate to detect large deletion >300 kb but lacked sensitivity to detect the deletion restricted to a single exon, as observed in family A. MLPA was accurate to detect large deletions but the probes targeting the exon 1, 2 and 12 are located outside the exons and therefore could miss a deletion restricted to one exon located outside the probes. Advantages and weaknesses of the different techniques are presented in S8 Table. Overall, targeted capture sequencing of PKP2 appears as the most appropriate technique as it has probably the best sensitivity for detection of large deletions through coverage depth analysis and is able to detect point or small ins/del mutations at the same time [25].

Genetic overlap with other cardiomyopathies

The analysis of 96 genes associated with various inherited cardiomyopathies identified 4 putative pathogenic variants in EYA4, COX15, PSNE1 and RBM20. The COX15 variant did not segregated with the disease and was unlikely to be disease-causing. One patient with severe biventricular involvement that progressed to end-stage heart failure and heart transplantation carried a deleterious PSEN1 missense variant (p.Tyr189Cys). Mutations in this gene, associated with Alzheimer disease, were previously reported in severe progressive dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) [20]. Another proband with classical ARVC/D phenotype associating RV involvement, T-wave inversion in precordial leads, epsilon wave and RV tachycardia carried a rare deleterious RBM20 missense variant. RBM20 mutations located within a highly-conserved arginine/serine (RS)-rich region gene were previously identified in familial DCM [18,19]. However, the rare variant p.Arg761Qln is located outside this mutational hot-spot and thus remains of unknown significance. Furthermore, the PSEN1 and the RBM20 variant frequencies were 0.02% in the 1000 genome database, which appears high in the setting of this rare disease. Another missense variant predicted as deleterious was found in EYA4, a gene associated with progressive DCM and hearing loss [17]. However, no hearing anomaly was documented in the family. Although these putative variants were retained through highly stringent process, it remains difficult to conclude on their pathogenicity in absence of functional and large familial segregation studies, whereas the RBM20 and the EYA4 variants were also identified in the affected relative. A putative deletion of ABCC9 was also identified in one ARVC/D proband and was considered of unknown significance. ABBC9 mutations were previously identified in DCM patients with ventricular arrhythmias [26]. Overlapping phenotypes between DCM and right ventricular cardiomyopathies were described with other genes, such as LMNA and PLN. We cannot exclude that some of these “new” candidate genes, previously associated with DCM, could be associated with ARVC/D phenotype. Further analyses are therefore needed to determine the role of these genes in ARVC/D: screening in larger cohorts, large familial segregation and functional studies but also additional WES studies in other ARVC/D cohorts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we observed a rather high 5.7% frequency of large deletions in ARVC/D as the cause of gene-negative ARVC/D undetected by conventional Sanger sequencing, suggesting need for systematic routine screening of such mutations. Coverage depth analysis through NGS (targeted capture sequencing or WES), which has become the reference sequencing method, appears as an accurate method to detect such deletions. This finding reinforces haploinsufficiency as the major pathophysiological mechanism of PKP2 mutations in ARVC/D. We also identified putative deleterious genetic variants in four associated-cardiomyopathy genes, possibly expanding the genetic spectrum of ARVC/D.

Supporting information

50% coverage reduction was observed in patient U.1 (red line) compared to controls, indicating a probable PKP2 heterozygous deletion of all exons (mean PKP2 coverage ranged between 169 and 325 reads in controls).

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Number of missense variant, non-sense variant and Indel present with a frequency less than 0,1% of the control cohort are represented here.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Mean ±SD of triplicates. Patient A4 serves as control.

(DOCX)

Mean ±SD of triplicates. Patient A4 serves as control.

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Myobank–AFM (Institut de Myologie Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France) for the collection of heart samples from ARVC/D patients.

Abbreviations

- ARVC/D

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia

- CNV

Copy Number Variation

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- HRM

High Resolution Melt

- MLPA

Multiplex-Ligation-dependent-Probe-Amplification

- NGS

Next generation sequencing

- qPCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- RV

Right ventricle

- WES

Whole exome sequencing

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris [PHRC programme hospitalier de recherche AOM n°05073], “Fédération Française de Cardiologie”/“Société Française de Cardiologie” and “Ligue contre la cardiomyopathie”. J. Fedida was supported by a grant from the Federation Française de Cardiologie. We thank Myobank – AFM (Institut de Myologie Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France) for the collection of heart samples from ARVC/D patients.

References

- 1.Fressart V, Duthoit G, Donal E, Probst V, Deharo J-C, Chevalier P, et al. Desmosomal gene analysis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: spectrum of mutations and clinical impact in practice. Europace. Juin 2010;12(6):861–8. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basso C, Corrado D, Marcus FI, Nava A, Thiene G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. The Lancet. 11;373(9671):1289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the Task Force Criteria. Eur Heart J 2010;31:806–14. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quarta G, Muir A, Pantazis A, Syrris P, Gehmlich K, Garcia-Pavia P, et al. Familial evaluation in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: impact of genetics and revised task force criteria. Circulation 2011;123:2701–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrado D, Wichter T, Link MS, Hauer RNW, Marchlinski FE, Anastasakis A, et al. Treatment of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia: An International Task Force Consensus Statement. Circulation 2015;132:441–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ackerman MJ, Priori SG, Willems S, Berul C, Brugada R, Calkins H, et al. HRS/EHRA Expert Consensus Statement on the State of Genetic Testing for the Channelopathies and Cardiomyopathies. Europace 2011;13:1077–109. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Mura IEA, Bauce B, Nava A, Fanciulli M, Vazza G, Mazzotti E, et al. Identification of a PKP2 gene deletion in a family with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. November 2013;21(11):1226–31. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts J, Herkert J, Rutberg J, Nikkel S, Wiesfeld A, Dooijes D, et al. Detection of genomic deletions of PKP2 in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Clinical Genetics. 2013;83(5):452–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01950.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ott P, Marcus FI, Sobonya RE, Morady F, Knight BP, Fuenzalida CE. Cardiac sarcoidosis masquerading as right ventricular dysplasia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol PACE 2003;26:1498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiso N, Stephan DA, Nava A, Bagattin A, Devaney JM, Stanchi F, et al. Identification of mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene in families affected with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 2 (ARVD2). Hum Mol Genet 2001;10:189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otten E, Asimaki A, Maass A, van Langen IM, van der Wal A, de Jonge N, et al. Desmin mutations as a cause of right ventricular heart failure affect the intercalated disks. Heart Rhythm Off J Heart Rhythm Soc 2010;7:1058–64. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quarta G, Syrris P, Ashworth M, Jenkins S, Zuborne Alapi K, Morgan J, et al. Mutations in the Lamin A/C gene mimic arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2011. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Zwaag PA, van Rijsingen IAW, Asimaki A, Jongbloed JDH, van Veldhuisen DJ, Wiesfeld ACP, et al. Phospholamban R14del mutation in patients diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy or arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: evidence supporting the concept of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:1199–207. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen AH, Andersen CB, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Haunso S, Svendsen JH. Mutation analysis and evaluation of the cardiac localization of TMEM43 in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Clin Genet 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01623.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015. May;17(5):405–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vite A, Gandjbakhch E, Prost C, Fressart V, Fouret P, Neyroud N, et al. Desmosomal Cadherins Are Decreased in Explanted Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy Patient Hearts. PLoS ONE. 23 September 2013;8(9):e75082 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schönberger J, Wang L, Shin JT, Kim SD, Depreux FFS, Zhu H, et al. Mutation in the transcriptional coactivator EYA4 causes dilated cardiomyopathy and sensorineural hearing loss. Nat Genet. avr 2005;37(4):418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo W, Schafer S, Greaser ML, Radke MH, Liss M, Govindarajan T, et al. RBM20, a gene for hereditary cardiomyopathy, regulates titin splicing. Nat Med 2012;18:766–73. doi: 10.1038/nm.2693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brauch KM, Karst ML, Herron KJ, de Andrade M, Pellikka PA, Rodeheffer RJ, et al. Mutations in ribonucleic acid binding protein gene cause familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:930–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li D, Parks SB, Kushner JD, Nauman D, Burgess D, Ludwigsen S, et al. Mutations of presenilin genes in dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:1030–9. doi: 10.1086/509900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christensen AH, Benn M, Bundgaard H, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Haunso S, Svendsen JH. Wide spectrum of desmosomal mutations in Danish patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Med Genet. November 2010;47(11):736–44. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.077891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox MGPJ, Zwaag PA van de, Werf C van der, Smagt JJ van der, Noorman M, Bhuiyan ZA, et al. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy Pathogenic Desmosome Mutations in Index-Patients Predict Outcome of Family Screening: Dutch Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy Genotype-Phenotype Follow-Up Study. Circulation. 2011. June 14;123(23):2690–700. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.988287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray B, Wagle R, Amat-Alarcon N, Wilkens A, Stephens P, Zackai EH, et al. A family with a complex clinical presentation characterized by arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy and features of branchio-oculo-facial syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2013. February;161A(2):371–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rigato I, Bauce B, Rampazzo A, Zorzi A, Pilichou K, Mazzotti E, et al. Compound and digenic heterozygosity predicts lifetime arrhythmic outcome and sudden cardiac death in desmosomal gene-related arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013;6:533–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng Y, Chen D, Wang G-L, Zhang VW, Wong L-JC. Improved molecular diagnosis by the detection of exonic deletions with target gene capture and deep sequencing. Genet Med. 2015. February;17(2):99–107. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bienengraeber M, Olson TM, Selivanov VA, Kathmann EC, O’Cochlain F, Gao F, et al. ABCC9 mutations identified in human dilated cardiomyopathy disrupt catalytic KATP channel gating. Nat Genet. 2004. April;36(4):3382–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

50% coverage reduction was observed in patient U.1 (red line) compared to controls, indicating a probable PKP2 heterozygous deletion of all exons (mean PKP2 coverage ranged between 169 and 325 reads in controls).

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Number of missense variant, non-sense variant and Indel present with a frequency less than 0,1% of the control cohort are represented here.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Mean ±SD of triplicates. Patient A4 serves as control.

(DOCX)

Mean ±SD of triplicates. Patient A4 serves as control.

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.