Abstract

Background

National heart failure (HF) hospitalization rates have not been appropriately age-standardized by sex or race/ethnicity. Reporting hospital utilization trends by subgroup is important for monitoring population health and developing interventions to eliminate disparities.

Methods and Results

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) was used to estimate the crude and age-standardized rates of HF hospitalization between 2002 and 2013 by sex and race/ethnicity. Direct standardization was used to age-standardize rates to the 2000 U.S. standard population. Relative differences between subgroups were reported. The national age-adjusted HF hospitalization rate decreased 30.8% from 526.86 to 364.66 per 100,000 between 2002 and 2013. While hospitalizations decreased for all subgroups, the ratio of the age-standardized rate for males compared to females increased from 20% greater to 39% (p-for-trend=0.002) between 2002 and 2013. Black males had a rate that was 229% (p-for-trend=0.141) and black females 240% (p-for-trend=0.725) with reference to whites in 2013 with no significant change between 2002 and 2013. Hispanic males had a rate that was 32% greater in 2002 and the difference narrowed to 4% (p-for-trend=0.047) greater in 2013 relative to whites. For Hispanic females the rate was 55% greater in 2002 and narrowed to 8% greater (p-for-trend=0.004) in 2013 relative to whites. Asian/Pacific Islander (PI) males had a 27% lower rate in 2002 that improved to 43% (p-for-trend=0.040) lower in 2013 relative to whites. For Asian/PI females the hospitalization rate was 24% lower in 2002 and improved to 43% (p-for-trend=0.021) lower in 2013 relative to whites.

Conclusions

National HF hospitalization rates have decreased steadily over the recent decade. Disparities in HF burden and hospital utilization by sex and race/ethnicity persist. Significant population health interventions are needed to reduce the HF hospitalization burden among blacks. The evaluation of factors explaining the improvements in the HF hospitalization rates among Hispanics and Asian/PI are needed.

Keywords: health disparities, hospitalization, heart failure, race and ethnicity, trends

Heart failure (HF) is the fourth leading cause of hospitalization and the leading cause of hospitalization for cardiovascular conditions in the United States.1 Among adults over the age of 85, HF is the number one cause of hospitalization.1 The total number of primary HF hospitalizations per year in the United States has been steady at approximately 1 million for the past decade.2,3 In 2012, an estimated 5.7 million American adults had HF based on self-report.2 By 2030 the prevalence of HF is expected to increase 46% to over 8 million people secondary to an aging demographic nationally.4 However, national prevalence estimates based on self-report are likely lower than the true HF prevalence as 31% to 57% of patients underreport a HF diagnosis.5,6 The prevalence of HF is also not equally distributed by sex and race/ethnicity.7 Projected total costs for HF medical care are expected to increase from $20.9 billion in 2012 to $53.1 billion in 2030 with 80% of expenditures attributed to hospitalization.4 Approximately 80% of the medical costs related to HF result from inpatient hospital care.4 The Affordable Care Act prioritizes the containment of hospitalization costs and whether preventable hospitalizations will be reduced secondary to the expanded insurance markets needs to be observed.8

Limited data exists on the trends and differential HF hospitalization rates by sex and race/ethnicity, particularly when applying appropriate statistical age-standardization. Demographically standardized hospitalization rates are a useful marker of differences in the HF hospitalization burden. Subgroups defined by race/ethnicity, sex, socioeconomic status, and region are disproportionally burdened by cardiovascular diseases and HF.9 Population differences in cardiovascular risk factors, access to care, and insufficient public health efforts underlie measured differences in HF burden.10 A standardized marker of health differences assists in targeting interventions towards vulnerable populations and monitoring the response to interventions over time. We analyzed the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), an all-payer dataset that represents acute-care hospital utilization nationally, to estimate the age-standardized rates for adult HF hospitalizations and relative differences by sex and race/ethnicity between 2002 and 2013.

Methods

Data Sources

The NIS dataset provides hospital administrative data through the Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The NIS datasets were obtained for the years 2002 to 2013. Each year of the NIS contains a sample of 7 to 8 million hospital discharges. The NIS redesigned its sampling strategy in 2012 to improve national estimates. Prior to 2012, the NIS sampled approximately all hospitalization records from 1,000 hospitals (a 20% hospital sample). After 2012, the NIS sampled 20% of all records from approximately 4,300 participating hospitals. Additionally, long-term acute care hospitals were excluded beginning with the 2012 NIS. The redesign’s exclusion of long-term acute care hospitals decreased the total number of discharges by 0.7%. Trend weights were applied for 2002 to 2011 dataset to account for shifts in sampling strategy. Trend weights for 2012 and 2013 are not currently available and recommended, standard weights were utilized. The unit of analysis in the NIS is a discharge; therefore, readmissions are not identified. The NIS sampling frame covers over 95% of the United States population and 94% of all community hospital discharges.11

Study Cohort

HF was defined by any International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code (online-only Data Supplement Table I) that mentioned a HF syndrome. A primary HF hospitalization was defined as any HF ICD-9-CM discharge code used as the first listed discharge code. Patients <18 years were excluded. The definition used for a primary HF admission is consistent with prior publications.3,12 Race/ethnicity was classified as white, black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander (PI), or Native American as captured by administrative hospital data. Native Americans were not included in the study because of their small sample size and unreliable estimates.

Statistical analysis

Within the NIS, racial/ethnic classification was missing for approximately 27.5% of the sample in 2002. Race/ethnicity coding improved in more recent years with 4.6% missing in the 2013 NIS. The missing racial/ethnic data is unlikely to be missing completely at random. Certain states in the early years of the NIS are known to have withheld racial/ethnic classification. For all NIS datasets, missing race/ethnicity was imputed using a multinomial logistic model using age, sex, insurance status, comorbid conditions, hospital region and characteristics. This method adheres to the recommendations provided by HCUP for handling missing racial/ethnic data.13 Calculating HF hospitalization rates by race/ethnicity would be significantly underestimated without imputation. The primary purpose of the imputation was to normalize population-based estimates and not reliably identify the racial/ethnic classification for any single HF hospitalization.

United States Census estimates were used for each sex and racial/ethnic subgroup to calculate crude and age-standardized rates per 100,000 persons. For each year of the NIS, the number of adult HF hospitalizations per single-year of life were estimated by sex and race/ethnicity. HF hospitalization rates were age-standardized for the 2000 United States standard population using the direct standardization method. Direct standardization used single-year of life age-adjustments to limit any residual bias related shifts in the age distribution within subgroups. Variance estimation used modified gamma intervals.14 Statistical significance for the hospitalization rate trend analysis used a nonparametric Wilcoxon-type rank sum test.15 All estimation procedures were performed with the appropriate NIS survey weights to account for the sampling strategy in STATA 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics are provided for patient characteristics, select comorbidities, hospital length of stay, and inpatient mortality. Institutional IRB provided exemption for this project.

Results

HF Hospitalizations, Mortality, and Patient Characteristics

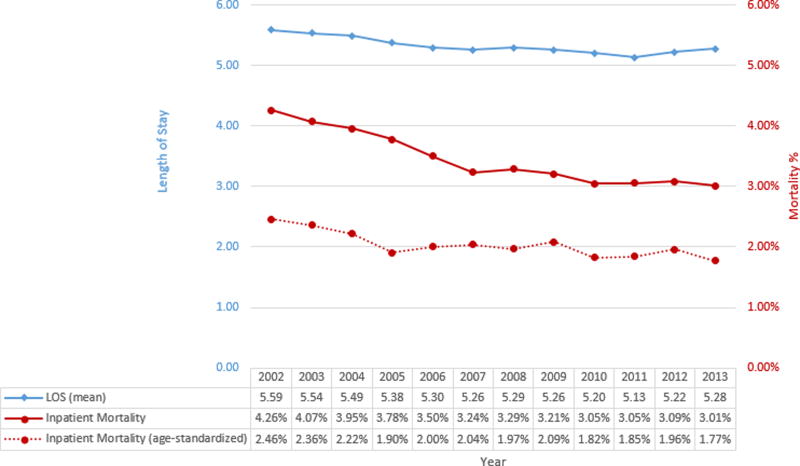

Between 2002 and 2013 there were an estimated 12,783,478 primary HF hospitalizations nationally. The average age was approximately 72 years nationally, the proportion of minority patients increased over time, and select comorbidities were generally more frequent in later years (Table 1, online-only Data Supplement Table III). The mean length of stay decreased slightly from 5.59 days to 5.28 between 2002 and 2013, while the crude and age-standardized rates for inpatient mortality improved modestly (Figure 1). The difference in the mean length of stay between subgroups is minimal (online-only Data Supplement Figure IA, IB). Inpatient mortality is higher for whites when compared to other subgroups and the difference is decreased when age-adjusted (online-only Data Supplement Figure IIA, IIB). The average age at hospitalization was approximately 75 years for women, 70 for men, 75 for whites, 63 for blacks, 69 for Hispanics, and 72 for Asians/PI (online-only Data Supplement Table II). The total number of national HF hospitalizations decreased 14.4% from 1,122,064 in 2002 to 960,124 in 2013 (Table 2). The national crude HF hospitalization rate decreased 24.2% from 522.49 per 100,000 in 2002 to 395.86 in 2013 (online-only Data Supplement Figure IIIA, Table VIII). The national age-standardized HF hospitalization rate fell 30.8% (average 3.3% per year) from 526.86 in 2002 to 364.66 per 100,000 in 2013 (online-only Data Supplement Figure IIIB). The national male age-standardized HF hospitalization rate decreased 25.8% from 581.69 in 2002 to 431.40 per 100,000 in 2013. Females had a 36.0% decrease in the age-standardized HF hospitalization rate from 486.20 in 2002 to 310.99 per 100,000 in 2013. With respect to disposition at discharge, the proportion of patients discharged to home remained relatively constant while the proportion discharged to skilled nursing and intermediate care facilities increased (online-only Data Supplement Table IV, V, VI).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for the national HF cohort for select years 2002, 2007, 2013 from the National Inpatient Sample.

| 2002 | 2007 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 72.90 | 72.48 | 72.27 |

| Female | 54.74% | 51.34% | 49.03% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 70.40% | 66.55% | 64.34% |

| Black | 18.01% | 20.09% | 19.23% |

| Hispanic | 7.13% | 7.82% | 7.37% |

| Asian/PI | 1.59% | 1.80% | 1.91% |

| Census Region | |||

| New England | 4.77% | 6.56% | 4.98% |

| Mid Atlantic | 16.30% | 13.09% | 15.03% |

| East North Central | 16.42% | 18.48% | 16.75% |

| West North Central | 7.23% | 6.06% | 6.18% |

| South Atlantic | 26.30% | 25.06% | 21.92% |

| East South Central | 5.95% | 4.48% | 7.69% |

| West South Central | 7.92% | 10.43% | 11.30% |

| Mountain | 2.03% | 3.66% | 4.19% |

| Pacific | 13.08% | 12.17% | 11.96% |

| Primary Payer | |||

| Medicare | 76.35% | 74.11% | 74.85% |

| Medicaid | 6.56% | 7.46% | 8.08% |

| Private Insurance | 13.11% | 12.78% | 11.08% |

| Self-Pay | 2.29% | 3.29% | 3.48% |

| No Charge | 0.21% | 0.41% | 0.38% |

| Other | 1.42% | 1.80% | 2.00% |

| Comorbidities† | |||

| HTN | 58.73% | 65.39% | 70.92% |

| CAD | 27.49% | 29.54% | 32.23% |

| Atrial fibrillation | 12.94% | 15.20% | 17.77% |

| Obese | 18.72% | 20.18% | 32.40% |

| Valve Disease | 16.80% | 19.82% | 22.29% |

| VT | 5.09% | 6.08% | 7.14% |

| AMI | 1.68% | 1.89% | 2.28% |

| PVD | 4.14% | 4.88% | 6.60% |

| DM | 33.23% | 35.22% | 38.81% |

| COPD | 17.31% | 17.65% | 17.74% |

| Anemia | 19.17% | 22.42% | 30.01% |

| Fluid/Electrolyte | 19.10% | 24.12% | 31.87% |

PI = Pacific Islander, HTN = hypertension, CAD = coronary artery disease, VT = ventricular tachycardia, AMI = acute myocardial infarction, PVD = peripheral vascular disease, DM = diabetes mellitus, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Age-standardized proportions to 2000 U.S. standard population.

Figure 1.

Trends in national heart failure hospitalization length of stay and inpatient mortality from the National Inpatient Sample. LOS = length of stay, age-standardized to the 2000 U.S. standard population.

Table 2.

Absolute number of HF hospitalizations per year from 2002 to 2013 from the National Inpatient Sample.

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | 1,122,064 | 1,170,708 | 1,154,020 | 1,127,778 | 1,133,112 | 1,061,987 | 1,050,087 | 1,051,715 | 997,224 | 1,003,419 | 951,220 | 960,124 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 507,777 | 536,711 | 541,949 | 539,530 | 548,631 | 516,532 | 513,538 | 521,006 | 499,459 | 497,152 | 476,925 | 489,180 |

| Female | 614,212 | 633,783 | 611,809 | 588,049 | 584,403 | 545,263 | 536,380 | 530,635 | 497,751 | 506,188 | 474,275 | 470,760 |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White | 789,931 | 810,712 | 797,887 | 814,026 | 770,023 | 706,717 | 726,624 | 714,236 | 651,953 | 668,969 | 642,535 | 648,730 |

| Black | 202,068 | 206,212 | 218,580 | 177,492 | 215,143 | 213,375 | 195,084 | 198,172 | 213,006 | 204,510 | 190,595 | 192,290 |

| Hispanic | 79,959 | 101,268 | 87,227 | 88,380 | 94,629 | 83,098 | 724,555 | 78,944 | 75,192 | 76,159 | 68,885 | 73,210 |

| Asian/PI | 17,884 | 19,202 | 18,924 | 15,154 | 17,994 | 19,165 | 18,640 | 18,357 | 18,450 | 15,525 | 17,640 | 18,905 |

PI = Pacific Islander

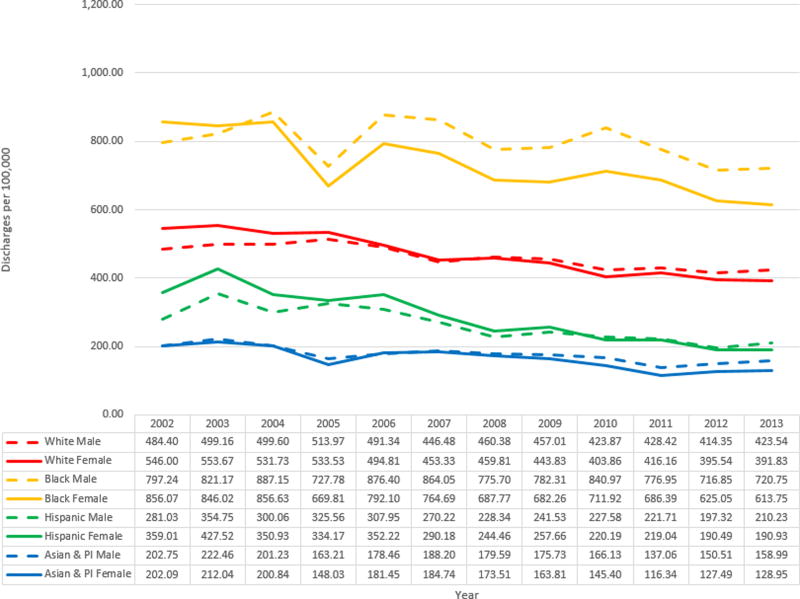

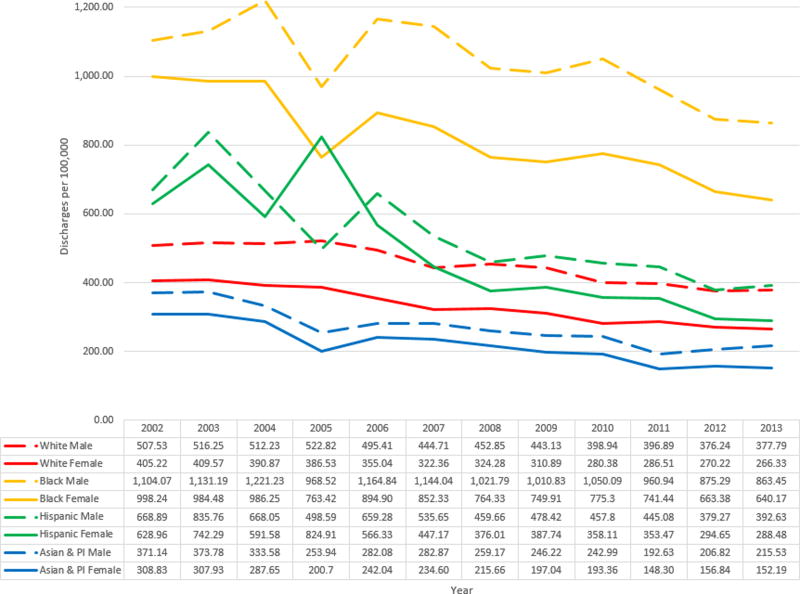

HF Hospitalizations by Race/Ethnicity

After imputation for missing race/ethnicity data, the crude hospitalization rate for Hispanics was noted to be lower than whites (Figure 2A, online-only Data Supplement Figure IVA). Imputation for missing racial/ethnic classification did not considerably shift the proportional representation of each racial/ethnic group in the sample (online-only Data Supplement Table VII). Hispanics have a higher hospitalization rate than whites when age-standardized (Figure 2B, online-only Data Supplement Figure IVB). The age-standardized HF hospitalization rate decreased 29.6% for whites from 448.29 in 2002 to 315.69 per 100,000 in 2013. For blacks, the age-standardized HF hospitalization rate decreased 29.4% from 1048.31 in 2002 to 739.72 per 100,000 in 2013. Hispanics had a greater 48.4% decrease in age-standardized HF hospitalization rate 649.53 in 2002 to 335.41 per 100,000 in 2013. For Asian/PI, the age-standardized HF hospitalization rate decreased 47.5% from 342.85 in 2002 to 179.90 per 100,000 in 2013.

Figure 2.

A: National crude hospitalization rate by race/ethnicity and sex from the National Inpatient Sample. B: National age-standardized hospitalization rate by race/ethnicity and sex from the National Inpatient Sample. PI = Pacific Islander

When comparing sex within racial/ethnic subgroups, the age-standardized HF hospitalization rate for men is uniformly higher than the rate for women across all groups except for Hispanics in the 2005 NIS (Figure 2B). The 2005 NIS had a lower representation of all racial/ethnic minority groups and the rate of hospitalization was higher for Hispanic females compared to males. The difference in age-standardized hospitalization rates between males and females was greatest for blacks followed by whites, Hispanic, and Asians/PI.

Relative Differences in HF Hospitalization Rates

The crude HF hospitalization rates generally reveal a smaller difference between subgroups. The ratio of the age-standardized HF hospitalization rate for males compared to females increased from 20% greater to 39% between 2002 and 2013 (p-for-trend = 0.002) and the absolute difference in rate was mostly unchanged (p-for-trend = 0.870) (Table 3). Black males had a rate that was 229% (p-for-trend=0.141) and black females 240% (p-for-trend=0.725) referenced to whites in 2013 with no significant change between 2002 and 2013. Hispanic males had a rate that was 32% greater in 2002 and the relative difference narrowed to 4% (p-for-trend=0.047) greater in 2013 relative to whites. Similarly, for Hispanic females the rate was 55% greater in 2002 and narrowed to 8% greater (p-for-trend=0.004) in 2013 relative to whites. males had a 27% lower rate in 2002 that improved to 43% (p-for-trend=0.040) lower in 2013 relative to whites. Similarly, for Asian/PI females the hospitalization rate was 24% lower in 2002 and improved to 43% (p-for-trend=0.021) lower in 2013 relative to whites. Relative differences between female minority groups and whites mirrored the differences reported between male subgroups.

Table 3.

Measures of difference in the age-standardized HF hospitalization rate by sex and race/ethnicity from the National Inpatient Sample.

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | p-trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male* | |||||||||||||

| Ratio | 1.20 (1.19–1.20) | 1.21 (1.21–1.22) | 1.26 (1.26–1.27) | 1.31 (1.31–1.32) | 1.33 (1.33–1.34) | 1.34 (1.33–1.34) | 1.35 (1.35–1.36) | 1.37 (1.37–1.38) | 1.37 (1.37–1.38) | 1.34 (1.34–1.34) | 1.36 (1.35–1.36) | 1.39 (1.38–1.39) | 0.002 |

| Excess | 95.49 (93.43–97.55) | 105.70 (103.64–107.76) | 123.58 (121.56–125.60) | 138.93 (136.98–140.88) | 144.34 (142.41–146.27) | 133.12 (131.30–134.94) | 134.54 (132.76–136.32) | 138.41 (136.67–140.15) | 129.14 (127.47–130.81) | 117.88 (116.24–119.52) | 113.93 (112.37–115.49) | 120.32 (118.79–121.85) | 0.870 |

| Male† | |||||||||||||

| Black | |||||||||||||

| Ratio | 2.18 (2.17–2.18) | 2.19 (2.18–2.20) | 2.38 (2.38–2.39) | 1.85 (1.84–1.86) | 2.35 (2.34–2.36) | 2.57 (2.57–2.58) | 2.26 (2.25–2.26) | 2.28 (2.27–2.29) | 2.63 (2.62–2.64) | 2.42 (2.41–2.43) | 2.33 (2.32–2.33) | 2.29 (2.28–2.29) | 0.141 |

| Excess | 596.54 (588.61–604.47) | 614.94 (606.96–622.92) | 709.00 (700.74–717.26) | 445.70 (438.48–452.92) | 669.43 (661.58–677.28) | 699.33 (691.03–707.03) | 568.94 (561.72–576.16) | 567.70 (560.68–574.72) | 651.15 (644.21–658.09) | 564.05 (557.51–570.59) | 499.05 (492.93–505.17) | 485.66 (479.69–491.63) | 0.112 |

| Hispanic | |||||||||||||

| Ratio | 1.32 (1.31–1.33) | 1.62 (1.61–1.63) | 1.30 (1.29–1.32) | 0.95 (0.94–0.96) | 1.33 (1.32–1.34) | 1.20 (1.19–1.22) | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 1.08 (1.07–1.09) | 1.15 (1.14–1.16) | 1.12 (1.11–1.13) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | 0.047 |

| Excess | 161.36 (153.68–169.04) | 319.51 (311.18–327.84) | 155.82 (148.67–162.97) | −24.23 (−29.312–−19.14) | 163.87 (157.14–170.60) | 90.94 (85.17–96.71) | 6.81 (1.53–12.09) | 35.29 (30.06–40.52) | 58.86 (53.63–64.09) | 48.19 (43.14–53.24) | 3.03 (−1.48–7.54) | 14.84 (10.39–19.29) | 0.047 |

| Asian/PI | |||||||||||||

| Ratio | 0.73 (0.71–0.75) | 0.72 (0.70–0.75) | 0.65 (0.63–0.67) | 0.49 (0.46–0.51) | 0.57 (0.55–0.59) | 0.64 (0.61–0.66) | 0.57 (0.55–0.59) | 0.56 (0.53–0.58) | 0.61 (0.59–0.63) | 0.49 (0.46–0.51) | 0.55 (0.53–0.57) | 0.57 (0.55–0.59) | 0.040 |

| Excess | −136.39 (−144.95–−127.83) | −142.47 (−150.68–−134.26) | −178.65 (−186.13–−171.17) | −268.88 (−275.19–−262.57) | −213.33 (−219.89–−206.77) | −161.84 (−168.09–−155.59) | −193.68 (−199.47–−187.89) | −196.91 (−202.41–−191.41) | −155.95 (−161.40–−150.50) | −204.26 (−208.93–−199.59) | −169.42 (−174.10–−164.74) | −162.26 (−166.88–−157.64) | 0.528 |

| Female† | |||||||||||||

| Black | |||||||||||||

| Ratio | 2.46 (2.46–2.47) | 2.40 (2.40–2.41) | 2.52 (2.52–2.53) | 1.98 (1.97–1.98) | 2.52 (2.51–2.53) | 2.64 (2.64–2.65) | 2.36 (2.35–2.36) | 2.41 (2.41–2.42) | 2.77 (2.76–2.77) | 2.59 (2.58–2.59) | 2.45 (2.45–2.46) | 2.40 (2.40–2.41) | 0.725 |

| Excess | 593.02 (587.01–599.03) | 574.91 (568.98–580.84) | 595.38 (589.53–601.23) | 376.89 (371.77–382.01) | 539.86 (534.41–545.31) | 529.97 (524.72–535.22) | 440.05 (435.11–444.99) | 439.02 (434.18–443.86) | 494.92 (490.04–499.80) | 454.93 (450.20–459.66) | 393.16 (388.74–397.58) | 373.84 (369.56–378.12) | 0.015 |

| Hispanic | |||||||||||||

| Ratio | 1.55 (1.54–1.56) | 1.81 (1.80–1.82) | 1.51 (1.50–1.52) | 2.13 (2.12–2.14) | 1.60 (1.59–1.60) | 1.39 (1.38–1.40) | 1.16 (1.15–1.17) | 1.25 (1.24–1.26) | 1.28 (1.27–1.29) | 1.23 (1.22–1.24) | 1.09 (1.08–1.10) | 1.08 (1.07–1.09) | 0.004 |

| Excess | 223.74 (217.58–229.90) | 332.72 (326.19–339.25) | 200.71 (195.04–206.38) | 438.38 (430.12–446.64) | 211.29 (206.05–216.53) | 124.81 (120.29–129.33) | 51.73 (47.65–55.81) | 76.85 (72.81–80.89) | 77.73 (72.81–80.89) | 66.96 (63.16–70.76) | 24.43 (21.06–27.80) | 22.15 (18.89–25.41) | 0.003 |

| Asian/PI | |||||||||||||

| Ratio | 0.76 (0.74–0.78) | 0.75 (0.73–0.77) | 0.74 (0.72–0.76) | 0.52 (0.50–0.54) | 0.68 (0.66–0.70) | 0.73 (0.71–0.75) | 0.67 (0.64–0.69) | 0.63 (0.61–0.65) | 0.69 (0.67–0.71) | 0.52 (0.49–0.54) | 0.58 (0.56–0.60) | 0.57 (0.55–0.59) | 0.021 |

| Excess | −96.39 (−102.94–−89.84) | −101.64 (−107.97–−95.31) | −103.22 (−109.11–−97.33) | −185.83 (−190.58–−181.08) | −113.00 (−118.05–−107.95) | −87.76 (−92.55–−82.97) | −108.62 (−113.10–−104.14) | −113.85 (−118.02–−109.68) | −87.02 (−91.16–−82.88) | −138.21 (−141.75–−134.67) | −113.38 (−116.87–−109.89) | −114.14 (−117.46–−110.82) | 0.199 |

Values are presented as ratios or excess number of admissions per 100,000. 95% confidence intervals in parentheses.

PI = Pacific Islander, Ratio = ratio of age-standardized hospitalization rate over reference, Excess = difference in age-standardized hospitalization between subgroup and reference.

reference group is female

reference group is white

Discussion

Overall, we find positive and reassuring findings that hospital utilization for HF is decreasing nationally when adjusting for the aging population. The age-standardized primary HF hospitalization rate has decreased steadily between 2002 and 2013 in the United States. This suggest that improvements in the outpatient management of HF and the expansion of evidenced based medical and device therapies may have lowered the national hospitalization burden. Moreover, the decreasing hospitalization rate likely correlates with a lower age-standardized prevalence of HF from gains in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease between 2002 and 2013. Despite these overall improvements, the HF hospitalization burden for males has increased relative to females. In addition, the high HF hospitalization ratio among blacks relative to whites has not decreased over the recent decade, while Hispanics and Asian/PI more rapidly reduced their HF hospitalization rates relative to whites.

The decline in the national age-standardized HF hospitalization rate is generally consistent with prior observational studies. The crude national hospitalization rate of HF was estimated to decline 26.9% between 2001 and 2009.12 Using Medicare administrative data, the crude rate of hospitalization decreased 31.2% from 2,845 per 100,000 person-years in 1998 to 1,957 per 100,000 person-years in 2008.16 Crude rates are helpful in measuring per capita hospitalization utilization while age-standardized rates allow for accurate subgroup comparisons and remove age-related bias when trending rates over time. Prior research reporting the national HF hospitalization trends using the NIS were limited and did not follow the Center for Disease Control age-adjustment recommendations.3,12,17

Both crude and age-standardized inpatient mortality rates improved nationally despite more prevalent comorbid conditions and minimal decreases in length of stay. The lower inpatient mortality rates suggest progressive improvement in the hospital management of primary HF admissions. Whites experience a higher inpatient mortality when compared to other race/ethnic groups that may reflect a comparatively higher burden of admissions with later stages of disease. While inpatient mortality rates have decreased, the proportion of patients discharged to home was relatively constant and the proportion discharged to skilled nursing or intermediate facilities increased. One in five hospitalized HF patients were discharged to an extended care facility, which is associated with a greater risk of death and readmission when controlling for patient factors.18 Given the chronic HF care needs, evaluating the number of days at home and the quality of life after a HF discharge necessitates increased research attention.19

While our results indicate a decreasing HF burden on average, the improvements are not equally distributed across subpopulations based on sex and race/ethnicity. Relative differences by sex and race/ethnicity have either improved, stagnated, or worsened. For males between 2002 and 2013, the relative difference in the HF hospitalization burden has increased relative to females. This pattern has not been as perceptible since women are a larger proportion of the general HF population given their longer life expectancies.20

With respect to race/ethnicity, the difference in the burden of HF is striking. Black males and females have a nearly two and half fold higher age-standardized hospitalization rates when compared to whites and the disparity has not narrowed relative to whites over the last decade. The relative difference between blacks and whites is underappreciated when looking at crude rates that do not account for the younger age-distribution of minority groups. The higher HF hospitalization burden among blacks reflects the much higher morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease in the population and the loss of preventable life years. Additionally, hospitalizations impart a greater financial cost to the healthcare system, particularly in comparison to preventative strategies aimed at reducing the incidence of HF and acute decompensations of pre-existing HF. In contrast, Hispanics had a 44.9% greater HF hospitalization rate in 2002 when compared to whites. The relative difference between Hispanics and whites narrowed considerably to 6.2% in 2013. For Asians/PI, the age-standardized HF hospitalization rate continued to improve relative to whites and is now nearly half their rate.

There has been limited exploration of the differential HF burden by race/ethnicity. Community surveillance from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study between 2005 to 2009 noted the highest HF hospitalization and readmission rates was among black men, followed by black women, white men and the lowest among white women.21 Work on the differences in the incidence of HF between racial/ethnic groups was reported in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. After a median follow-up of 4 years between 2000 and 2002, blacks had the highest crude incident rate of 460 followed by Hispanics at 350, whites at 240, and Chinese Americans at 100 per 100,000.22 While this was a high-quality cohort study with objective echocardiographic evaluation, the number of events (n=79 with new HF) were relatively small to make precise subgroup estimates. The measured difference in incidence rate in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis is similar in magnitude to the measured difference in the age-standardized hospitalization rates between racial/ethnic groups in the 2002 NIS. Therefore, age-standardized hospitalization rate ratios may be a useful surrogate for the relative incidence rate of HF between subgroups.

Race/ethnic associations with cardiovascular disease, incident heart failure, and heart failure hospitalizations may be strongly confounded by social and socioeconomic status in the United States. There is a strong suggestion that discrimination and chronic stress contribute to adverse cardiovascular health among marginalized minority groups, but additional research is required to isolate causal factors.23,24 The higher hospitalization burden among blacks and Hispanics is more reflective of underlying determinants of health rather than genetic or physiologic differences.25 A study from the Women’s Health Initiative, found that the excess risk of incident HF among black women was primarily attributable to diabetes and lower household incomes.26 Furthermore, the study was unable to attribute the lower risk among Hispanics and Asian/PI women to measured risk factors. Compared to patient or household level SES measurements, neighborhood deprivation indices have been reported as stronger risk factors for rehospitalization risk.27 Thus, a threshold for poverty and poor neighborhood conditions may be more predictive of adverse health outcomes.

Despite a higher HF hospitalization rates compared to whites, Hispanics have narrowed the observed utilization difference over the last decade. Hispanics have a larger representation of foreign born residents that may contribute to a selection bias related to the healthy migrant effect.28 Foreign born populations are associated with a healthier cardiovascular risk profile.29 Acculturation of immigrant communities is found to parallel progressively poorer cardiovascular health in the United States29 Recent population trends indicate a lower rate of foreign-born Hispanic immigrants and higher numbers of native born.30 Whether the decreasing Hispanic HF hospitalization rates are sustainable given the increasing prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among Hispanics should be monitored.31 Strategies that reduce tobacco use and improve hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia control are expected to effectively reduce the HF burden within all subpopulations. Additionally, optimizing HF management with guideline directed medical therapies for those with prevalent disease is expected to reduce the national HF hospitalization burden further.

Limitations

Some limitations of the data deserve mention. Each NIS sampling unit is derived from a hospitalization and lacks unique patient identifiers; consequently, readmissions are not identified. The risk adjusted readmissions rate for Medicare patient with HF is approximately 23% within 30-days of admission.2 Of those readmissions, only 17% to 35% are for recurrent HF exacerbations.32 Therefore, studies using the NIS are not able to distinguish a unique HF hospitalization from a HF readmission. The number of states that participated in the NIS in 2002 was 35 covering 87% of the United States population and it increased to 44 states covering 97% of the United States population by 2013.33 Trend weights accounting for changes in the NIS sampling design are only available for data between 1998 and 2011.33 For 2012 and 2013, trend weights were not available and the standard survey weights were used. The NIS found that modifications in their hospital sampling strategy in 2012 may have decreased total hospitalization by 0.7% secondary to the exclusion of long-term acute care hospitals.33 The degree to which these modifications affect the HF hospitalization counts for 2012 and 2013 is unknown. Ethnicity data for Hispanic non-Hispanic is not ascertained as a separate variable in the NIS. As mentioned previously, racial/ethnic classification data is differentially missing between early and more recent years of the NIS. For the 2002 NIS, 27.51% of the sample lacked racial/ethnic classification while only 4.63% were missing for the 2013 NIS. To overcome this limitation, a multinomial logistic model using patient and hospital characteristics was used to impute race/ethnicity per NIS recommendations.13 Imputations may be insufficient to accurately correct crude and age-standardized HF hospitalization rates by race. For the 2005 NIS with lower minority representation, the 20% hospital sample likely did not capture a representative national sample or discharges missing race/ethnic classifications (27.5%) were disproportionately distributed among minorities. This unusual pattern of race/ethnic representation in the 2005 NIS was not observed for the other 11 years of the NIS.

The ICD-9 codes are not well validated for distinguishing between heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) patients without echocardiographic or chart abstracted data. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in the relative burden of HFrEF and HFpEF are well described. Women and whites have a higher risk for HFpEF compared to males and other race/ethnic groups.34 HFpEF patients also have a higher observed hospital readmission rate compared to HFrEF patients.35

Conclusions

The NIS is the largest representative dataset for all-payer hospitalizations in the United States. The NIS uses a robust weighted sample, 7 million of an estimated 35 million total hospitalizations per year. Current estimates for the national HF burden rely on cross-sectional survey data utilizing self-report or cohort studies without nationally representative sampling strategies.2,36 Despite its limitations, the NIS dataset provides a unique opportunity to understand the epidemiology of HF hospital utilization. These data may also serve as an important surrogate marker for a population’s cardiovascular health and the progress of health care interventions. This study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to report on the racial/ethnic differences in the national HF hospitalization rates between whites, blacks, Hispanics and Asians/PI. This is also the first study to appropriately age-standardize hospitalization rates using the 2000 United States standard million and single-year of life adjustments. Single-year of life adjustments effectively remove residual bias related to differential age distributions within 10-year or greater age intervals. Incomplete age standardization using larger strata would be expected to diminish the measured differences in rates when comparing subpopulations with younger age distributions between eras or racial/ethnic groups. The HF hospitalization rate reflects the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and incident HF within a given population.

Between 2002 and 2013 the age-standardized HF hospitalization and mortality rates have improved nationally. This confirms that despite an aging population, hospital utilization rates for HF have decreased. Unfortunately, differences in the HF hospitalization burden between males and females have not changed significantly over the reported period. Among minorities, blacks have a HF hospitalization rate that is nearly two and half fold higher than whites. The relative difference in the rate of HF hospitalization between blacks and whites has not narrowed over twelve years of observation. In contrast, the difference in HF hospitalization burden narrowed for Hispanics when compared to whites during the same period of observation. Asians/PI have consistently maintained the lowest rates of HF hospitalization when compared to all other racial/ethnic groups. The variation between subgroups in the HF hospitalization rates suggests a large portion of the burden is preventable through population health interventions. Age-standardized HF hospitalization rates are a useful metric of a population’s cardiovascular health and should be followed for targeting interventions and narrowing health disparities between groups over time.

Supplementary Material

What is known

The burden of cardiovascular disease is known to be higher among blacks compared to whites but differences in heart failure hospitalizations based on sex and racial/ethnic categorization, with appropriate age-standardization, is not well described.

What this study adds

Heart failure hospitalization disparities are greater for minorities when appropriately age-standardized.

The burden of heart failure hospitalizations is significantly higher for blacks when compared to whites with little change in the relative disparity over the past 12 years of observation.

Hispanics have a higher heart failure hospitalization rate with a narrowing of disparities over the same period of observation while Asians have a significantly lower rate of heart failure hospitalizations that’s been stable.

Significant population health interventions are needed to reduce the heart failure hospitalization burden.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: B. Ziaeian was supported by the NIH Cardiovascular Scientist Training Program (T32 HL007895). Vickie M. Mays was partially supported by NIH, NIMHD (0006932)

Gregg C. Fonarow receives research funding from the NIH and consulting fees from Amgen, Janssen, Medtronic, Novartis, and St Jude Medical.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The other authors report no disclosures.

References

- 1.Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Most Frequent Conditions in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. Rockville, Maryland: 2013. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb162.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després J-P, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blecker S, Paul M, Taksler G, Ogedegbe G, Katz S. Heart failure-associated hospitalizations in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1259–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, Ikonomidis JS, Khavjou O, Konstam MA, Maddox TM, Nichol G, Pham M, Piña IL, Trogdon JG. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the united states a policy statement from the american heart association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:606–619. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englert H, Muller-Nordhorn J, Seewald S, Sonntag F, Voller H, Meyer-Sabellek W, Wegscheider K, Windler E, Katus H, Willich SN. Is patient self-report an adequate tool for monitoring cardiovascular conditions in patients with hypercholesterolemia? J Public Health (Bangkok) 2010;32:387–394. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feinstein M, Ning H, Kang J, Bertoni A, Carnethon M, Lloyd-Jones DM. Racial differences in risks for first cardiovascular events and noncardiovascular death: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, the Cardiovascular Health Study, and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2012;126:50–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.057232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.No A, Street D, York NEW, Apt PST, Ct NEWH. 2009 Tax Reporting Statement National Financial Services LLC Private Access : Visit Us Online : 2009 Dividends and Distributions Form 1099-INT * 2009 Interest Income Form 1099-MISC * 2009 Miscellaneous Income Summary of 2009 Proceeds From Broker and Barte. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonow RO, Grant AO, Jacobs AK. The cardiovascular state of the union: Confronting healthcare disparities. Circulation. 2005;111:1205–1207. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160705.97642.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mensah Ga, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2013. Rockville, Maryland: 2015. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Dharmarajan K, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National trends in heart failure hospital stay rates, 2001 to 2009. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1078–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houchens R. HCUP Methods Series Report # 2015-01. Rockville, Maryland: 2015. Missing Data Methods for the NIS and the SID. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/methods.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Consonni D, Coviello E, Buzzoni C, Mensi C. A command to calculate age-standardized rates with efficient interval estimation. Stata J. 2012;12:688–701. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med. 1985;4:87–90. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780040112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Normand S-LT, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–2008. Jama. 2011;306:1669–1678. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age Adjustment Using the 2000 Projected U.S. Population. Hyattsville, Maryland: 2001. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statnt/statnt20.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen LA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Curtis LH, Dai D, Masoudi FA, Bhatt DL, Heidenreich PA, Fonarow GC. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility and subsequent clinical outcomes among older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Hear Fail. 2011;4:293–300. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groff AC, Colla CH, Lee TH. Days Spent at Home — A Patient-Centered Goal and Outcome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1610–1612. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta PA, Cowie MR. Gender and heart failure: a population perspective. Heart. 2006;92(Suppl 3):iii14–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.070342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang PP, Chambless LE, Shahar E, Bertoni AG, Russell SD, Ni H, He M, Mosley TH, Wagenknecht LE, Samdarshi TE, Wruck LM, Rosamond WD. Incidence and survival of hospitalized acute decompensated heart failure in four US communities (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study) Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, Olson J, Shea S, Liu K, Burke GL, Lima JAC. Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2138–45. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kershaw KN, Lewis TT, Roux AVD, Jenny NS, Liu K, Penedo FJ, Carnethon MR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and inflammation among men and women: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Heal Psychol. 2016;35:343–350. doi: 10.1037/hea0000331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Everson-Rose SA, Lutsey PL, Roetker NS, Lewis TT, Kershaw KN, Alonso A, Diez Roux AV. Perceived discrimination and incident cardiovascular events. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182:225–234. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eaton CB, Abdulbaki AM, Margolis KL, Manson JE, Limacher M, Klein L, Allison MA, Robinson JG, Curb JD, Martin LA, Liu S, Howard BV. Racial and ethnic differences in incident hospitalized heart failure in postmenopausal women: The women’s health initiative. Circulation. 2012;126:688–696. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kind AJH, Jencks S, Brock J, Yu M, Bartels C, Ehlenbach W, Greenberg C, Smith M. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:765–774. doi: 10.7326/M13-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennedy S, Kidd MP, McDonald JT, Biddle N. The Healthy Immigrant Effect: Patterns and Evidence from Four Countries. J Int Migr Integr. 2015;16:317–332. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daviglus ML, Pirzada A, Talavera GA. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in the hispanic/latino population: Lessons from the hispanic community health study/study of latinos (HCHS/SOL) Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;57:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krogstad JM, Lopez MH. Hispanic Nativity Shift. Washington, D.C.: 2014. Available from: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/04/29/hispanic-nativity-shift/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report — United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:1–189. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. The Prevention of Hospital Readmissions in Heart Failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;58:379–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houchens R, Ross D, Elixhauser A. HCUP Methods Series Report #2006-05. Rockville, Maryland: Using the HCUP National Inpatient Sample to Estimate Trends. (Revised 12/15/15). Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/methods.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eaton CB, Pettinger M, Rossouw J, Martin LW, Foraker R, Quddus A, Liu S, Wampler NS, Hank Wu W-C, Manson JE, Margolis K, Johnson KC, Allison M, Corbie-Smith G, Rosamond W, Breathett K, Klein L. Risk Factors for Incident Hospitalized Heart Failure With Preserved Versus Reduced Ejection Fraction in a Multiracial Cohort of Postmenopausal Women Clinical Perspective. Circ Hear Fail. 2016;9:e002883. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng RK, Cox M, Neely ML, Heidenreich PA, Bhatt DL, Eapen ZJ, Hernandez AF, Butler J, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction in the Medicare population. Am Heart J. 2014;168:721–730.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerber Y, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Chamberlain AM, Manemann SM, Jiang R, Killian JM, Roger VL. A contemporary appraisal of the heart failure epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:996–1004. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.