Abstract

Inhibition of Runx2 is one of many mechanisms that suppress bone formation in glucocorticoid (GC)-induced osteoporosis (GIO). We profiled mRNA expression in ST2/Rx2dox cells after treatment with doxycycline (dox; to induce Runx2) and/or the synthetic GC dexamethasone (dex). As expected, dex typically antagonized Runx2-driven transcription. Select genes, however, were synergistic stimulated and this was confirmed by RT-qPCR. Among the genes synergistically stimulated by GCs and Runx2 was Wnt inhibitory Factor 1 (Wif1), and Wif1 protein was readily detectable in medium conditioned by cultures co-treated with dox and dex, but neither alone. Cooperation between Runx2 and GCs in stimulating Wif1 was also observed in primary preosteoblast cultures. GCs strongly inhibited dox-driven alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity in control ST2/Rx2dox cells, but not in cells in which Wif1 was silenced. Unlike its antimitogenic activity in committed osteoblasts, induction of Runx2 transiently increased the percentage of cells in S-phase and accelerated proliferation in the ST2 mesenchymal pluripotent cell culture model. Furthermore, like the inhibition of Runx2-driven ALP activity, dex antagonized the transient mitogenic effect of Runx2 in ST2/Rx2dox cultures, and this inhibition eased upon Wif1 silencing. Plausibly, homeostatic feedback loops that rely on Runx2 activation to compensate for bone loss in GIO are thwarted, exacerbating disease progression through stimulation of Wif1.

The efficacy of pharmacological glucocorticoids (GCs) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases is blemished by metabolic adverse effects, including GC-induced osteoporosis (GIO) (Frenkel et al., 2015). A hallmark of GIO is extreme inhibition of bone formation. Early after commencement of GC administration, the inhibition of bone formation is associated with accelerated bone resorption, and some 10% of bone mass can be lost in the first year of treatment. But even later, when resorption rates drop below physiological levels, bone loss continues due to extremely low osteoblast number and function (Frenkel et al., 2015). Suppression of bone formation persists as long as GCs are administered, and rebounds with treatment cessation (Laan et al., 1993).

The master regulator Runx2 controls osteoblast differentiation and bone formation during both embryogenesis and postnatal life (Komori et al., 1997; Otto et al., 1997; Ducy et al., 1999; Adhami et al., 2015). GCs inhibit the Runx2-driven transcription of myriad target genes (Koromila et al., 2014). Suppression of the Runx2 gene itself (Chang et al., 1998; Pereira et al., 2002) has also been reported, although it is likely secondary to post-translational inhibition of Runx2 activity (Koromila et al., 2014). Many other mechanisms compromise osteogenesis in GIO, most notably inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway as well as down-regulation of growth factors and their receptors and downstream kinases (Frenkel et al., 2015). A question remains, however, why adaptive mechanisms that normally respond to bone loss with stimulation of osteoblastogenesis fail to stimulate bone formation in GIO.

Several steroid hormones have been shown to post-translationally inhibit Runx2 in the osteoblast and other cell lineages, potentially attributable to physical interaction with their respective nuclear receptors (Chang et al., 1998; Kawate et al., 2007; Khalid et al., 2008; Baniwal et al., 2009). Many exceptions, however, have been reported, including cases where androgens, estrogens, as well as 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3, cooperate with Runx2 in stimulating specific target genes (Paredes et al., 2004; Baniwal et al., 2012b). Using a prostate cancer cell model, we have recently demonstrated locus-dependent interaction between Runx2 and the androgen receptor (AR). While Runx2 and AR inhibit each other at most of their target genes, a minority of these genes is synergistically stimulated (Little et al., 2014). Here, we tested this concept for the case of the interaction between Runx2 and GCs in mesenchymal pluripotent cells. Among the minority of genes synergistically stimulated by Runx2 and GCs is Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (Wif1), which may block biomechanical feedback loops triggered by bone loss in GIO and exacerbate disease progression.

The pivotal role of Wnt signaling in osteoblastogenesis and bone formation has been demonstrated by skeletal phenotypes associated with naturally occurring, as well as experimental mutations of various components of the pathway (Monroe et al., 2012; Baron and Kneissel, 2013). In the canonical Wnt pathway, Wnt ligands bind co-receptors composed of frizzled and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (Lrp) 5/6 (Bhanot et al., 1996; Tamai et al., 2000). Receptor activation leads to the escape of β-catenin from a destruction complex that includes adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc), glycogen synthase kinase (Gsk3), and Axin. β-catenin then accumulates and translocates to the cell nucleus, where it co-activates LEF/TCF target genes (Monroe et al., 2012; Baron and Kneissel, 2013). Activation of frizzled receptors by Wnt ligands can also affect LEF/TCF-independent cellular functions through activation of the non-canonical planar cell polarity and the calcium pathways (Liu et al., 1999). A variety of Wnt inhibitors that control canonical and/or non-canonical Wnt signaling have been implicated in bone mass control (Monroe et al., 2012; Baron and Kneissel, 2013), and several of them have been specifically implicated in GIO (Frenkel et al., 2015). These include Dkk1, which inhibits canonical Wnt signaling by targeting the Lrp co-receptor (Ohnaka et al., 2004), as well as the decoy Frizzled receptor Sfrp1 (Wang et al., 2005). Like Sfrp1, Wif1 functions as a decoy receptor and inhibits both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling (Hsieh et al., 1999). Our finding that Runx2 and GCs synergistically stimulate Wif1 in pluripotent mesenchymal progenitor cells therefore provide a novel insight to GIO: feedback loops otherwise activated to promote Runx2-driven bone formation in response to skeletal weakening would now block osteoblastogenesis instead.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Construction of the murine ST2/Rx2dox cell line with the doxycycline (dox)-inducible Runx2 cassette has been described (Baniwal et al., 2012a). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA). For osteoblast differentiation, cultures at 90% confluency were treated with 50 μg/ml L-ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 10 mM β-Glycerophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich). Newborn mouse calvarial osteoblast (NeMCO) cultures were prepared from 2 days old newborn mice at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (Memphis, TN) under an approved IACUC protocol and in accordance with the guidelines of the NIH (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 1996). Parietal bones were excised, free of sutures, and then digested as previously described (Krum et al., 2008). Cells were maintained in alpha minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were transfected with pCMV-OSF2 (RUNX2, a gift from Dr. Gerard Karsenty) using the Nucleofector Kit (Lonza). Dox (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) and dexamethasone (dex, from Sigma–Aldrich) were added to culture media at final concentrations of 200 ng/ml and 1 μM, respectively, unless otherwise indicated.

Microarray analysis

ST2/Rx2dox cells were treated with dox and/or dex for 48 h, and total RNA from quadruplicate experiments was extracted using Aurum™ Total RNA mini-kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) and subjected to expression microarray analysis using MouseRef-8 v2.0 Expression BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Gene expression raw data processing was performed using GenomeStudio (Illumina). Differential gene expression was analyzed using Partek Genomics Suite™ 6.4 (Partek, Inc., St. Louis, MO).

Quantitative RT-qPCR

Between 0.7 and 1 μg RNA, extracted as above, was reverse-transcribed using qScript™ cDNA SuperMix synthesis kit (Quanta BioSciences, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Quantitative Real Time PCR was carried out in triplicates using a CFX96 instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA), the Maxima SYBR Green/Fluorescein Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the primers listed in Supplemental Table S1. Relative mRNA expression values were normalized to those of either 18S RNA (ST2 cells) or Gapdh mRNA (NeMCO), which themselves varied minimally across samples.

Western blot

Cell layers were washed with PBS and proteins were extracted using a 50 mM Tris-HCl lysis buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and fresh protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). For detection of secreted Wif1, proteins were precipitated from 72-h conditioned medium using 20% trichloroacetic acid and suspended in the same lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) and aliquots diluted in Laemmli buffer were subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to Amersham Hybond™-P PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), and hybridized with either rabbit monoclonal antibodies against Wif1 (ab155101; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against RUNX2 (M-70; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX) or goat antibodies against β-Actin (sc-1616; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX). Proteins were visualized using HRP-conjugated donkey antigoat (sc-2033) and goat anti-rabbit (sc-2004) antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and the Pierce ECL2 western blotting detection system (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Gene silencing

For WifI silencing, specific Mission-shRNA lentiviral plasmids (TRCN0000089190 and TRCN0000089191) and a negative control shRNA plasmid (SHC002) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For packaging, the plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293T cells along with helper plasmids pMD.G1 and pCMV. R8.91 using jetPRIME transfection reagent (Polyplus-transfection S.A., Illkirch-Graffenstaden, France). ST2/Rx2dox cells were transduced with the lentiviral particles followed by selection with 5 μg/ml Puromycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for at least 1 week.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining

ST2/Rx2dox cells were treated as indicated for 6 days in 12-well plates and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 min. Staining was performed using ALP detection kit (EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and the ALP-positive area was quantified using the ImageJ64 software package.

Cell proliferation and cell cycle analysis

Cell proliferation was assessed using a colorimetric assay based on the reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cells were grown to 90% confluency in 48-well plates, treated as indicated, and then incubated with 0.5 mg/ml of MTT for 4h prior to lysis with DMSO. Absorbance was measured at a 595 nm wavelength using Victor3V™ plate reader (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT). For cell cycle profiling, cells were stained with propidium iodide and percentage of cells in G1, S, and G2/M was determined by flow cytometry using a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and the Modfit LT software package (Verity Software House).

Results

GCs synergize with Runx2 in stimulating a select gene set

In a previous study investigating modulation of several handpicked Runx2 target genes by GCs, dex attenuated to various extents dox-(Runx2)-driven gene expression in ST2/Rx2dox cells undergoing osteoblast differentiation (Koromila et al., 2014). Taking a genome-wide approach, the present study confirms that GCs globally attenuate responses to Runx2 in the ST2/Rx2dox model system. This is demonstrated by the volcano plot in Figure 1A, describing effects of dex on genes that were either stimulated or inhibited in response to dox alone. Specifically, genes stimulated by Runx2dox alone (red in Fig. 1A), were generally inhibited in response to dex (in the presence of dox). Reciprocally, genes repressed by Runx2 alone were generally less repressed in the presence of dex (blue in Fig. 1A). The volcano plot also highlights a unique group of eight genes (Fig. 1A, top right and Supplemental Table S2), which were strongly stimulated by dex in the presence of dox (≥8-fold, P < 1e-08), even though most of them were not significantly affected by dox alone (indicated by gray color in Fig. 1A). While two of them (Ehd3 and BC022765) were merely dex-responsive (Supplemental Table S2), the remaining were synergistically stimulated by the co-treatment with dex and dox (Supplemental Table S2). Thus, although GCs most commonly interact with Runx2 to attenuate its effects on target genes, our microarray analysis disclosed unusual cases of synergism, where Runx2 and GCs together strongly stimulate genes that respond to each of them relatively weakly or not at all.

Fig. 1.

GCs synergize with Runx2 in stimulating a select gene set. (A) ST2/Rx2dox mesenchymal pluripotent cells were treated for 48 h in quadruplicate with vehicle control (C), dox (to induce Runx2; D), the synthetic GC dex (1 μM; G), or dox and dex together (DG). Global gene expression was profiled using the Illumina BeadChip platform and the response of genes to dex in the presence of dox is illustrated as a volcano plot, with red and blue symbols representing genes that were stimulated or repressed, respectively, by dox alone (D/C ≥ 2 or D/C ≤ −2, respectively; FDR P < 0.05). Data representing genes that did not significantly respond to dox alone by these criteria are in gray. NC, no change. Triangles represent genes that were strongly stimulated by dex in the absence of dox (G/C ≥ 5, FDR P < 0.05). Dashed lines highlight a set of 8 genes at the top right that were strongly stimulated (≥ 8 fold; P < 1e–08) by dex in the presence of dox. (B–G) ST2/Rx2dox cells were treated for 24, 48, or 72 h with dox and/or dex at the depicted concentrations, and expression of the indicated genes was measured by RT-qPCR. Data are means and SDs (n = 3) relative to the control values at 24 h, defined as 1. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com].

We performed an independent, validation experiment by treating ST2/Rx2dox cells with dox (to induce Runx2) and/or dex, followed by RT-qPCR analysis of genes that displayed in the microarray study the strongest Runx2-dependent dex-mediated stimulation. To further characterize the combinatorial regulation of these genes by Runx2 and dex, cells were treated with either 1 μM (as in the microarray experiment) or 0.1 μM dex for either 24 h, 48 h (as in the microarray experiment), or 72 h. As shown in Figure 1B–G, the RT-qPCR analysis confirmed the synergistic stimulation between Runx2 and dex. In some cases, such as Psca (Fig. 1B) and Serpina3h (Fig. 1D), dex synergized with Runx2 even though it had an inhibitory effect on its own. In other cases, for example, C3, the RT-qPCR analysis disclosed dex-mediated stimulation of gene expression in the absence of dox, but the stimulation was much stronger in the presence of dox (Fig. 1F). For almost every gene and every condition, with only two exceptions (Fig. 1C, 72 h and Fig. 1D, 24 h), the highest expression levels were observed in cultures co-treated with dox and dex. Thus, while generally antagonizing Runx2 (Fig. 1A), GCs synergize with Runx2 in stimulating select genes.

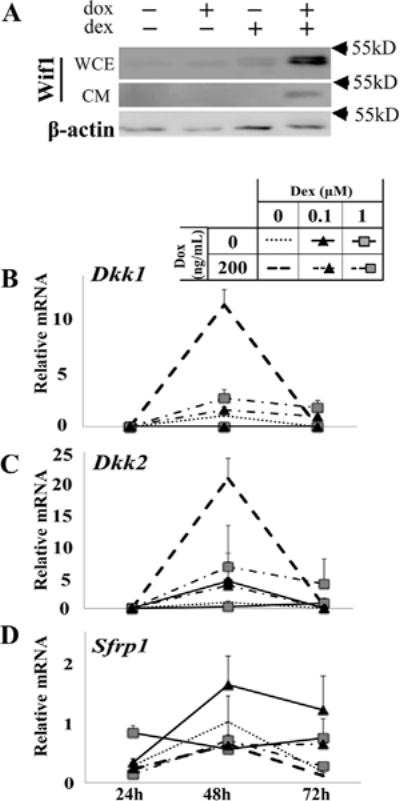

Robust synergistic stimulation of Wif1 by Runx2 and GCs is unique among Wnt antagonists

Wif1 is one of the genes most strongly stimulated by cotreatment with dox (to induce Runx2) and dex (Fig. 1G). Thus, in the presence of pharmacological GCs in vivo, stimulation of Runx2 may result in Wif1-mediated blockade of Wnt signaling, a pathway critical for cell replication, differentiation, and survival in the osteoblast lineage (Monroe et al., 2012; Baron and Kneissel, 2013). We therefore tested the co-regulation of Wif1 by GCs and Runx2 at the protein level. ST2/Rx2dox cells were treated with dox and/or dex for 72 h and Wif1 was measured by Western blot analysis of the cell lysates and the conditioned media. Wif1 protein was either undetectable or hardly detectable in the untreated cultures or after treatment with dox or dex alone, but was readily detectable in both the cell layer and the conditioned medium obtained from cultures co-treated with dox and dex (Fig. 2A). We next tested by RT-qPCR whether GCs and Runx2 cooperated in stimulating other Wnt antagonists previously implicated in GIO. Dkk1, which is stimulated by GCs in human and rat osteoblasts (Ohnaka et al., 2004; Mak et al., 2009), was not significantly stimulated by dex in ST2 mesenchymal progenitor cells (Fig. 2B). Dkk2, which is stimulated by GCs in primary NeMCO cultures (Gabet et al., 2011), was stimulated only transiently in ST2 cells and only at the 0.1 μM dex concentration (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, Runx2 stimulated both Dkk1 (11-fold at 48 h; Fig. 2B) and Dkk2 (21fold at 48 h; Fig. 2C). However, dex did not augment, but in fact antagonized these Runx2 effects in ST2 cells. At the 72-h time point, expression of both Dkk1 and Dkk2 in the presence of dox returned to baseline. At this later time point, there was some evidence for cooperation between GCs and Runx2 (Fig. 2B and C), but not nearly at the magnitude observed with Wif1 (Fig. 1G). GC-mediated stimulation of Sfrp1, which was observed in both rat and mouse osteoblast cultures (Wang et al., 2005; Mak et al., 2009), was absent or weak in ST2 cells, and the presence of Runx2, either alone or with dex, did not increase Sfrp1 expression (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Robust synergistic stimulation of Wif1 by Runx2 and GCs is unique among Wnt antagonists. (A) ST2/Rx2dox cells were treated for 72 h as indicated and Wifi protein levels were assessed by Western blot analysis of either whole cell extracts (WCE) or conditioned media (CM). Western blot analysis of β-actin in the cell layer was carried out as control. (B–D) Expression of mRNAs for the indicated Wnt antagonists was measured as in Figure 1B–G. Data represent the means and SDs (n = 3) relative to the control values at 48 h (defined as I).

We further investigated the regulation of Wif1, Dkk1, Dkk2, and Sfrp1 in Day-3 newborn mouse calvarial osteoblast (NeMCO) cultures. Cells were transiently transfected with a Runx2-expressing or a control vector and treated for 72 h with either dex or vehicle. As shown in Figure 3A–B by RT-qPCR and Western blot analysis, dex and Runx2 cooperated in stimulating Wif1. As with the ST2 culture model, RT-qPCR analysis demonstrates that such cooperativity is shared by neither Dkk1, nor Dkk2, nor Sfrp1 (Fig. 3C–E).

Fig. 3.

Synergistic stimulation of Wif1 by Runx2 and GCs in primary osteoblast cultures. Pre-osteoblasts isolated from newborn mouse calvariae were transiently transfected with RUNX2 or a control plasmid and then treated for 72 h with 1.0 μM dex or vehicle. Expression of the indicated genes was assessed by either Western blot analysis of whole cell extracts (A) or (B–E). (F, G) Untransfected cells were treated with differentiation medium on day 2 of culture. Dex (1 μM) or vehicle was added for 72 h before lysis, followed by Western blot analysis of Runx2 (F) and RT-qPCR analysis of Wif1 (G) on days 5 and 7. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

We next examined the dependence of GC-mediated Wif1 stimulation on Runx2 by determining the effect of dex on Wif1 expression in more mature NeMCO cultures, in which endogenous Runx2 is turned on. Similar to previous reports describing inhibition of endogenous Runx2 by GCs (Chang et al., 1998; Pereira et al., 2002), dex down-regulated Runx2 protein levels in day-7 NeMCO cultures (Fig. 3F). However, consistent with a demonstrated anabolic effect that transient GC administration has on osteoblast cultures prior to their commitment to terminally differentiate (Leclerc et al., 2004), dex stimulated Runx2 expression in earlier, day-5 NeMCO cultures (Fig. 3F). Supporting the role of Runx2 in GC-mediated Wif1 stimulation, dex no longer stimulated Wif1 when Runx2 was down-regulated on day 7 (Fig. 3G). These results are in line with our conclusion from the ST2 culture system that GCs cooperate with Runx2 to stimulate Wif1.

GCs inhibit expression of neither Axin2 nor Ccnd1 in ST2 pluripotent mesenchymal cells

To investigate the role of Wif1 in GC-mediated inhibition of Runx2-driven osteoblast differentiation, we engineered three ST2/Rx2dox sub-lines constitutively expressing either a nonspecific shRNA (shNS) or hairpin RNAs that target Wif1 (shWif11 or shWif12). First, we documented by RT-qPCR analysis >90% decrease in Wif1 mRNA in ST2/Rx2dox/shWif11 and ST2/Rx2dox/shWifi2 compared to ST2/Rx2dox/shNS cells (Fig. 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, western blot analysis confirmed Wif1 knockdown at the protein level.

Fig. 4.

Effect of Wif1 silencing on Wnt target gene expression in ST2 cells expressing Runx2 and treated with GCs. A–B. ST2/Rx2dox cells were transduced with lentiviruses encoding a nonspecific hairpin RNA (shNS) or either of two hairpins (shWif11 or shWif12) targeting distinct regioion in Wif1 mRNA. The derived shRNA-expressing sub-lines were treated for 72 h with dox and/or dex as indicated and Wif1 expression was measured by RT-qPCR (A, Mean ± SD; n = 3) and by Western blotting (B). +/− signs indicate presence or absence of dox and dex in both A and B. The RNA data in A are corrected for 18S RNA and Coomassie blue-stained proteins that remained in the SDS–PAGE gels after transfer are shown as a loading control in B. (C, D) The RNAs from Figure 4A were subjected to RT-qPCR analysis of Axin2 and Ccnd1 (mean ± SD, n = 3).

We treated the three ST2/Rx2dox sub-lines with dox and/or dex and measured expression of two canonical Wnt target genes, Axin2 and Ccnd1, using RT-qPCR. As expected, Wif1 silencing stimulated Axin2 expression (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, dox stimulated Axin2 expression in all three sub-lines (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the general attenuation of the Runx2 response (Fig. 1A and [Koromila et al., 2014]), dex attenuated, albeit weakly, the dox-mediated stimulation of Axin2, but surprisingly evidence for such attenuation was present only in the Wif1-depleted cells (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that GCs may employ pathways other than canonical Wnt signaling when inhibiting Runx2-driven osteoblast differentiation in the ST2 mesenchymal progenitor cells (Koromila et al., 2014). Further supporting this notion, dex did not attenuate dox-mediated stimulation of Ccnd1 expression in this culture model (Fig. 4D). In fact, dex on its own stimulated Ccnd1 expression, but interestingly this occurred only in Wif1-depleted cultures (Fig. 4D). The non-responsiveness to Wif1 silencing may reflect Wnt-unrelated regulation of Ccnd1 in ST2 cells (Fig. 4D).

Wif1 is required for GC-mediated antagonism of Runx2-driven alkaline phosphatase (ALP) stimulation in ST2 cells

To directly determine whether Wif1 plays any role in GC-mediated inhibition of Runx2-driven osteoblast differentiation in the ST2 culture model (Koromila et al., 2014), we investigated the effect of dex on Runx2-induced ALP activity in ST2/Rx2dox/shWif11 versus ST2/Rx2dox/shNS cells. Consistent with the reported effect of GCs in the parent ST2/Rx2dox cell line (Koromila et al., 2014), dex inhibited ALP activity in the dox-treated ST2/Rx2dox/shNS control sub-line by almost 70% compared to vehicle-treated cultures (Fig. 5). However, this inhibition amounted to less than 20% in the respective Wif1-depleted cultures (Fig. 5). Thus, despite the questionable effects of Wif1 and of GCs on canonical Wnt signaling in ST2 cells (Fig. 4C and D), Wif1 is clearly necessary for GC-inhibition of Runx2-driven osteoblast differentiation in this culture model.

Fig. 5.

Wif1 silencing mitigates GC-mediated suppression of Runx2-driven osteoblast differentiation. (A) ST2/Rx2dox cells expressing a non-specific shRNA (shNS) or one that targets Wif1 mRNA (shWif11) were treated for 6 days by dox and/or dex as indicated, and then subjected to ALP staining. (B) ALP activity was assessed as in A, and the stained area was quantified using the ImageJ software. Bars represent Mean ± SD values from three independent experiments, where the average stained area in the dox-treated cultures is defined as 100. *P < 0.05.

Wif1 silencing mitigates GC-mediated suppression of Runx2-driven proliferation in ST2 cells undergoing osteoblast differentiation

Reflecting reciprocity between cell proliferation and differentiation, the osteoblast master regulator Runx2 has been shown to promote cell cycle exit (Pratap et al., 2003; Lucero et al., 2013). Because Runx2-mediated stimulation of Ccnd1 expression (Fig. 4D) is inconsistent with this notion, we wondered whether it reflected a true mitogenic effect, and how it may be related to GIO and to Wif1. We treated control ST2/Rx2dox/shNS cultures and the Wif1-depleted ST2/Rx2dox/shWif11 cultures with dox and/or dex and initially analyzed their cell cycle profiles. As shown in Figure 6A and Supplemental Table S3, dox treatment almost doubled the percentage of ST2 cells in S-phase. Although dex decreased neither basal nor Runx2-stimulated Ccnd1 expression (Fig. 4D), it decreased the percentage of S-phase cells both at the baseline and in the presence of dox (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, the mitogenic and anti-mitogenic effects of Runx2 and GCs, respectively, were observed in cultures harvested on day 3, but not on day 6 (Fig. 6A), consistent with developmental stage-dependent regulation of osteoblast proliferation and differentiation (Smith et al., 2000; Gabet et al., 2011; Mikami et al., 2011). Thus, Runx2 and GCs appear to play opposing, mitogenic, and antimitogenic roles, respectively, as mesenchymal progenitor cells initiate differentiation toward the osteoblast phenotype.

Fig. 6.

Wif1 silencing mitigates GC-mediated suppression of Runx2-driven proliferation in mesenchymal pluripotent cells undergoing osteoblast differentiation. Quadruplicate ST2/Rx2dox cells expressing either shNS or shWif1 as in Figure 4 were treated as indicated commencing one day after plating (defined as Day 0). (A) Percentage of S-phase cells was determined by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. (B) Cell growth rates were calculated based on MTT assays as the differences between the day 4 values and the respective day 0 values (just prior to commencement of treatment), or between the day 7 values and the respective day 4 values. *P < 0.05. Complete raw data from the FACS and the MTT assays are presented in Supplemental Tables S3 and S4, respectively.

The mitogenic effect of Runx2 in day-3ST2 cell cultures was almost completely independent of Wif1, indicated by similar results obtained with the ST2/Rx2dox/shNS and the ST2/Rx2dox/shWif11 sub-lines (Fig. 6A). The same was true for the antimitogenic effect of dex in the absence of Runx2 (Fig. 6A). However, whereas the percentage of S-phase cells In dox-treated ST2/Rx2dox/shNS cells returned to near-control levels in response to dex, dex did not antagonize Runx2 with regard to cell cycle control in the Wif1-depleted cells (Fig. 6A). Consistent with the cell cycle profiling, MTT assays of ST2/Rx2dox cells within the first few days of culture demonstrated that dex inhibited proliferation both in the presence and absence of dox, and that the inhibition in the presence of dox was partially mitigated in the ST2/Rx2dox/shWif11 compared to the ST2/Rx2dox/shNS sub-lines (Fig. 6B). Thus, the synergistic stimulation of Wif1 by Runx2 and GCs (Fig. 1G) appears necessary for GC-mediated inhibition both cell proliferation and differentiation in mesenchymal pluripotent cells undergoing commitment to the osteoblast phenotype.

Discussion

Attenuation of Runx2 activity is one of many mechanisms potentially contributing to GIO (Frenkel et al., 2015). At first glance, our finding of synergism with Runx2 seems inconsistent with previously reported effects of GCs (7–9). We show, however, that GCs modulate the transcriptional activity of Runx2 in a locus-specific manner. While GCs generally attenuate effects of Runx2 on gene expression (Fig. 1A), exceptions to this general trend are not uncommon (Fig. 1A). In fact, we submit that genes synergistically stimulated by Runx2 and GC signaling (Fig. 1B–G), in particular Wif1, may play a critical role in GIO. Diverse effects of GCs on Runx2 is not unlike the recently reported locus-specific modulation of Runx2 activity by estrogens (Chimge et al., 2012), androgens (Little et al., 2014), and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (Stephens and Morrison, 2014), and is attributable in part to genomic distribution of their respective nuclear receptors relative to Runx2-occupied regions (Little et al., 2014).

Rapid bone loss that follows high-dose GC administration is due to both accelerated resorption and diminished formation (Frenkel et al., 2015). Importantly, adaption mechanisms normally activated by the ensuing mechanical overload seem to fail in GIO. Unlike postmenopausal osteoporosis, GIO is characterized by a blockade of bone formation, which can resume upon GC withdrawal (Laan et al., 1993). Extremely low bone formation rates despite bone loss, even in GC-treated children (Hansen et al., 2014), may be explained by synergism between Runx2 and GCs in stimulating anti-osteoblastogenic genes(s). Such synergism may constitute a vicious cycle, which prevents compensation for bone loss through Runx2-driven osteoblast differentiation (Fig. 7A). Other GIO mechanisms that inhibit osteoblast differentiation and function can be partially overcome, at least in principle, by stimulation of Runx2 and recruitment of osteoblasts to compensate for their compromised function. In the presence of pharmacological GCs, however, the coupling of such mechanisms to Wif1 stimulation would divert Runx2-driven osteoblastogenesis into a Runx2-driven blockade of Wnt signaling and thus exacerbation of GIO (Fig. 7A). Antagonism of Wif1 may therefore offer novel therapeutic approaches for the management of GIO. Although Wif1 is normally expressed during osteoblast differentiation (Baker et al., 2015), no overt phenotype, either skeletal or otherwise, has been reported in Wif1 knockout mice (Kansara et al., 2009). This normal baseline phenotype predicts little or no adverse reaction to in vivo administration of anti-Wif1 reagents. On the other hand, implementation of such putative therapeutic approaches must proceed with caution given the demonstrated protective role of Wif1 against osteosarcoma (Kansara et al., 2009; Baker et al., 2015).

Fig. 7.

GCs hijack Runx2. (A) Working model. Black arrow depicts adaptive circuits that enhance osteoblast-driven bone formation in response to bone loss (by any mechanism). GCs cause bone loss through a myriad of reported mechanisms (1), and at the same time synergize with Runx2 (2) to stimulate Wif1. Stimulation of Runx2 by homeostatic mechanisms is now hijacked to exacerbate GIO. (B) Schematic depiction of the transient expression of Runx2 at the initiation of osteoblast differentiation and the downregulation of Runx2 expression and/or genomic occupancy as the osteogenic program progresses (Komori, 2010; Meyer et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2015). C, Illustrative representation of results (Smith et al., 2000; Gabet et al., 2011; Mikami et al., 2011) suggesting that GCs do not inhibit osteoblast differentiation in vitro when administered at or after a time point that coincides with Runx2 down-regulation.

GCs engage multiple mechanisms to inhibit Wnt signaling in the osteoblast lineage (Frenkel et al., 2015). Among them, canonical Wnt signaling is inhibited by direct stimulation of Dkk1 expression (Ohnaka et al., 2004), indirect stimulation GSK3ß (Smith et al., 2002), and induction of transcription factors that interfere with ß-catenin-mediated LEF/TCF activation (Smith and Frenkel, 2005; Almeida et al., 2007). It is conceivable that adaptive activation of Runx2 in pluripotent mesenchymal cells could have potentially compensated for compromised Wnt signaling. Such an adaptive mechanism could also ameliorate bone loss due to GC-mediated stimulation of Sfrp1 (Wang et al., 2005), even though Sfrp1 inhibits both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling. Like Sfrp1, GC-mediated Wif1 induction is expected to block both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling (Hsieh et al., 1999). We envision at least two deleterious outcomes of Wif1 secretion from stromal pluripotent cells initiating osteoblast differentiation in the bone marrow space. First, secreted Wif1 might target in a paracrine manner dendritic processes projected from matrix-embedded osteocytes, the cells responsible for the bone anabolic effect of canonical Wnt signaling (Tu et al., 2015). This mechanism, however, is not unlike many others that could be at least partially overcome by Runx2-mediated stimulation of osteoblastogenesis. Through a second putative mechanism, however, secreted Wif1 might target its producing pre-osteoblasts in a paracrine manner, blocking both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling. Compensatory stimulation of Runx2 in the producing cell would fail to mount an osteogenic response because a vicious cycle is now turned on to further increase Wif1 biosynthesis and ablate both canonical and non-canonical Wnt-driven signals critical for osteoblast differentiation (Baron and Kneissel, 2013) (Fig. 7A).

Wif1 was among many genes previously reported to respond to GCs in vitro and in vivo (Yao et al., 2008; Naito et al., 2012). The present study assigns to Wif1 a critically unique role in GIO based on its synergistic stimulation by GCs and RUNX2 and the resistance of Wif1-depleted cells to GC-mediated inhibition of Runx2-driven osteoblast differentiation (Fig. 5). Wif1 also plays a role in GC-mediated antagonism of Runx2-driven cell proliferation (Fig. 6). Although Runx2 is traditionally considered an inhibitor of cell proliferation (Pratap et al., 2003; Galindo et al., 2005), its mitogenic property demonstrated here in ST2 cells is not without precedence (Chen et al., 2014). Mechanisms underlying the transient mitogenic effect of Runx2 in mesenchymal pluripotent cells initiating the osteoblast differentiation program remain to be explored. In particular, it would be important to clarify the potential role of the Wnt pathway. On one hand, a role for canonical Wnt signaling is suggested by the stimulation of Axin2 (Fig. 4C) and Ccnd1 (Fig. 4D). Stimulation of these genes, however, is insensitive to GCs and the associated Wif1 biosynthesis (Fig. 2A). Still, GCs antagonize the transient mitogenic effect of Runx2 in a Wif1-dependent manner (Fig. 6A), similar to their effect on Runx2-mediated induction of ALP (Fig. 5). Linkage between GC-mediated inhibition of osteoblast differentiation and a differentiation-related cell cycle has been noted previously (Smith et al., 2002). Furthermore, in order for GCs to inhibit osteoblast differentiation and the associated cell cycle, as well as to promote the linked adipogenesis in vitro, they must be administered early during phenotype development (Gabet et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2002; Mikami et al., 2011) (Fig. 7C). We speculate that the requirement for early GC administration is related to the transient nature of Runx2 expression/activity (Komori, 2010; Meyer et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2015); commencement of GC treatment at later time points does not inhibit development of the osteoblast phenotype possibly because Runx2 is down regulated (Fig. 7B).

In summary, this study validates previous observations of GC-mediated inhibition of Runx2, but more importantly it highlights exceptions where GCs do not inhibit, and even synergize with Runx2 in stimulating specific genes, including Wif1. Thus, induction of Runx2 in mesenchymal progenitor cells, intended to mount an osteogenic response to bone loss, would instead result in a Wnt blockade and exacerbation of GIO. Targeting Wif1 and/or the interaction between Runx2 and GCs at multiple co-stimulated genes may lead to novel therapeutic approaches for the management of GIO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

BF holds the J. Harold and Edna L. LaBriola Chair in Genetic Orthopaedic Research at the University of Southern California. The bioinformatics software and computing resources used in the analysis are funded by the USC Office of Research and the Norris Medical Library.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Contract grant numbers: DK071122, DK071122S, AR064354.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: None.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

Literature Cited

- Adhami MD, Rashid H, Chen H, Clarke JC, Yang Y, Javed A. Loss of Runx2 in committed osteoblasts impairs postnatal skeletogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:71–82. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, O’Brien CA, Manolagas SC. Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in osteoblast precursors by diverting beta-catenin from T cell factor- to forkhead box O-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27298–27305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EK, Taylor S, Gupte A, Chalk AM, Bhattacharya S, Green AC, Martin TJ, Strbenac D, Robinson MD, Purton LE, Walkley CR. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (WIF1) is a marker of osteoblastic differentiation stage and is not silenced by DNA methylation in osteosarcoma. Bone. 2015;73:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baniwal SK, Khalid O, Sir D, Buchanan G, Coetzee GA, Frenkel B. Repression ofRunx2 by androgen receptor (AR) in osteoblasts and prostate cancer cells: AR binds Runx2 and abrogates its recruitment to DNA. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:1203–1214. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baniwal SK, Shah PK, Shi Y, Haduong JH, Declerck YA, Gabet Y, Frenkel B. Runx2 promotes both osteoblastogenesis and novel osteoclastogenic signals in ST2 mesenchymal progenitor cells. Osteoporosis Int. 2012a;23:1399–1413. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1728-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baniwal SK, Little GH, Chimge NO, Frenkel B. Runx2 controls a feed-forward loop between androgen and prolactin-induced protein (PIP) in stimulating T47D cell proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 2012b;227:2276–2282. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: From human mutations to treatments. Nature Med. 2013;19:179–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanot P, Brink M, Samos CH, Hsieh JC, Wang Y, Macke JP, Andrew D, Nathans J, Nusse R. A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature. 1996;382:225–230. doi: 10.1038/382225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang DJ, Ji C, Kim KK, Casinghino S, McCarthy TL, Centrella M. Reduction in transforming growth factor beta receptor 1 expression and transcription factor CBFa1 on bone cells by glucocorticoid. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4892–4896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Ghori-Javed FY, Rashid H, Adhami MD, Serra R, Gutierrez SE, Javed A. Runx2 regulates endochondral ossification through control of chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:2653–2665. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimge NO, Baniwal SK, Luo J, Coetzee S, Khalid O, Berman BP, Tripathy D, Ellis MJ, Frenkel B. Opposing effects of Runx2 and estradiol on breast cancer cell proliferation: In vitro identification of reciprocally regulated gene signature related to clinical letrozole responsiveness. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:901–911. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Starbuck M, Priemel M, Shen J, Pinero G, Geoffroy V, Amling M, Karsenty G. A Cbfa1-dependent genetic pathway controls bone formation beyond embryonic development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1025–1036. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel B, White W, Tuckermann J. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2015;872:179–215. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2895-8_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabet Y, Noh T, Lee C, Frenkel B. Developmentally regulated inhibition of cell cycle progression by glucocorticoids through repression of cyclin A transcription in primary osteoblast cultures. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:991–998. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo M, Pratap J, Young DW, Hovhannisyan H, Im HJ, Choi JY, Lian JB, Stein JL, Stein GS, van Wijnen AJ. The bone-specific expression of Runx2 oscillates during the cell cycle to support a G1-related antiproliferative function in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20274–20285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413665200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KE, Kleker B, Safdar N, Bartels CM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in children. Semin Arthritis Rheumatism. 2014;44:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JC, Kodjabachian L, Rebbert ML, Rattner A, Smallwood PM, Samos CH, Nusse R, Dawid IB, Nathans J. A new secreted protein that binds to Wnt proteins and inhibits their activities. Nature. 1999;398:431–436. doi: 10.1038/18899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansara M, Tsang M, Kodjabachian L, Sims NA, Trivett MK, Ehrich M, Dobrovic A, Slavin J, Choong PF, Simmons PJ, Dawid IB, Thomas DM. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 is epigenetically silenced in human osteosarcoma, and targeted disruption accelerates osteosarcomagenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:837–851. doi: 10.1172/JCI37175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawate H, Wu Y, Ohnaka K, Takayanagi R. Mutual transactivational repression of Runx2 and the androgen receptor by an impairment of their normal compartmentalization. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;105:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid O, Baniwal SK, Purcell DJ, Leclerc N, Gabet Y, Stallcup MR, Coetzee GA, Frenkel B. Modulation of Runx2 activity by estrogen receptor-alpha: Implications for osteoporosis and breast cancer. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5984–5995. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, Shimizu Y, Bronson RT, Gao YH, Inada M, Sato M, Okamoto R, Kitamura Y, Yoshiki S, Kishimoto T. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts [see comments] Cell. 1997;89:755–764. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by Runx2. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;658:43–49. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1050-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koromila T, Baniwal SK, Song YS, Martin A, Xiong J, Frenkel B. Glucocorticoids antagonize RUNX2 during osteoblast differentiation in cultures of ST2 pluripotent mesenchymal cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:27–33. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krum SA, Miranda-Carboni GA, Hauschka PV, Carroll JS, Lane TF, Freedman LP, Brown M. Estrogen protects bone by inducing Fas ligand in osteoblasts to regulate osteoclast survival. EMBO J. 2008;27:535–545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laan RF, van Riel PL, van de Putte LB, van Erning LJ, van’t Hof MA, Lemmens JA. Low-dose prednisone induces rapid reversible axial bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Internal Med. 1993;119:963–968. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-10-199311150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc N, Luppen CA, Ho VV, Nagpal S, Hacia JG, Smith E, Frenkel B. Gene expression profiling of glucocorticoid-inhibited osteoblasts. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33:175–193. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0330175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little GH, Baniwal SK, Adisetiyo H, Groshen S, Chimge NO, Kim SY, Khalid O, Hawes D, Jones JO, Pinski J, Schones DE, Frenkel B. Differential effects of RUNX2 on the androgen receptor in prostate cancer: Synergistic stimulation of a gene set exemplified by SNAI2 and subsequent invasiveness. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2857–2868. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Liu T, Slusarski DC, Yang-Snyder J, Malbon CC, Moon RT, Wang H. Activation of a frizzled-2/beta-adrenergic receptor chimera promotes Wnt signaling and differentiation of mouse F9 teratocarcinoma cells via Galphao and Galphat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14383–14388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero CM, Vega OA, Osorio MM, Tapia JC, Antonelli M, Stein GS, van Wijnen AJ, Galindo MA. The cancer-related transcription factor Runx2 modulates cell proliferation in human osteosarcoma cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:714–723. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak W, Shao X, Dunstan CR, Seibel MJ, Zhou H. Biphasic glucocorticoid-dependent regulation of Wnt expression and its inhibitors in mature osteoblastic cells. Calcified Tissue Int. 2009;85:538–545. doi: 10.1007/s00223-009-9303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MB, Benkusky NA, Pike JW. The RUNX2 cistrome in osteoblasts: Characterization, downregulation following differentiation and relationship to gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:16016–16031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.552216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami Y, Lee M, Irie S, Honda MJ. Dexamethasone modulates osteogenesis and adipogenesis with regulation of osterix expression in rat calvaria-derived cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:739–748. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe DG, McGee-Lawrence ME, Oursler MJ, Westendorf JJ. Update on Wnt signaling in bone cell biology and bone disease. Gene. 2012;492:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito M, Omoteyama K, Mikami Y, Takahashi T, Takagi M. Inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling by dexamethasone promotes adipocyte differentiation in mesenchymal progenitor cells, ROB-C26. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;138:833–845. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-1007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnaka K, Taniguchi H, Kawate H, Nawata H, Takayanagi R. Glucocorticoid enhances the expression of dickkopf-1 in human osteoblasts: Novel mechanism of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto F, Thornell AP, Crompton T, Denzel A, Gilmour KC, Rosewell IR, Stamp GW, Beddington RS, Mundlos S, Olsen BR, Selby PB, Owen MJ. Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development [see comments] Cell. 1997;89:765–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes R, Arriagada G, Cruzat F, Villagra A, Olate J, Zaidi K, van Wijnen A, Lian JB, Stein GS, Stein JL, Montecino M. Bone-specific transcription factor Runx2 interacts with the lalpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor to up-regulate rat osteocalcin gene expression in osteoblastic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8847–8861. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8847-8861.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira RC, Delany AM, Canalis E. Effects of cortisol and bone morphogenetic protein-2 on stromal cell differentiation: Correlation with CCAAT-enhancer binding protein expression. Bone. 2002;30:685–691. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratap J, Galindo M, Zaidi SK, Vradii D, Bhat BM, Robinson JA, Choi JY, Komori T, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS, van Wijnen AJ. Cell growth regulatory role of Runx2 during proliferative expansion of preosteoblasts. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5357–5362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Frenkel B. Glucocorticoids inhibit the transcriptional activity of LEF/TCF in differentiating osteoblasts in a glycogen synthase kinase-3{beta}-dependent and -independent manner. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2388–2394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Redman RA, Logg CR, Coetzee GA, Kasahara N, Frenkel B. Glucocorticoids inhibit developmental stage-specific osteoblast cell cycle. Dissociation of Cyclin A-cdk2 from E2F4-p130 complexes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19992–20001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Coetzee GA, Frenkel B. Glucocorticoids inhibit cell cycle progression in differentiating osteoblasts via glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18191–18197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens AS, Morrison NA. Novel Target Genes of RUNX2 Transcription Factor and 1, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2014;115:1594–1608. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint-Jeannet JP, He X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature. 2000;407:530–535. doi: 10.1038/35035117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu X, Delgado-Calle J, Condon KW, Maycas M, Zhang H, Carlesso N, Taketo MM, Burr DB, Plotkin LI, Bellido T. Osteocytes mediate the anabolic actions of canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E478–E486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409857112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang FS, Lin CL, Chen YJ, Wang CJ, Yang KD, Huang YT, Sun YC, Huang HC. Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 modulates glucocorticoid attenuation of osteogenic activities and bone mass. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2415–2423. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W, Cheng Z, Busse C, Pham A, Nakamura MC, Lane NE. Glucocorticoid excess in mice results in early activation of osteoclastogenesis and adipogenesis and prolonged suppression of osteogenesis: A longitudinal study of gene expression in bone tissue from glucocorticoid-treated mice. Arthritis Rheumatism. 2008;58:1674–1686. doi: 10.1002/art.23454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Adisetiyo H, Little GH, Vangsness CT, Jr, Jiang J, Sternberg H, West MD, Frenkel B. Initial characterization of osteoblast differentiation and loss of RUNX2 stability in the newly established SK11 human embryonic stem cell-derived cell line. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:237–241. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.