Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to establish the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of the poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymerase inhibitor, veliparib, in combination with carboplatin in germline BRCA1- and BRCA2- (BRCA)-associated metastatic breast cancer (MBC), to assess the efficacy of single-agent veliparib, and of the combination treatment post-progression, and to correlate PAR levels with clinical outcome.

Patients and Methods

Phase I patients received carboplatin (AUC of 5–6, every 21 days), with escalating doses of oral twice-daily (BID) veliparib. In a companion phase II trial, patients received single-agent veliparib (400 mg BID) and upon progression, received the combination at MTD. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell PAR and serum veliparib levels were assessed and correlated with outcome.

Results

Twenty-seven phase I trial patients were evaluable. Dose-limiting toxicities were nausea, dehydration, and thrombocytopenia (MTD: veliparib 150 mg po BID and carboplatin [AUC of 5]). Response rate (RR) was 56%; 3 patients remain in complete response (CR) beyond 3 years. Progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 8.7 and 18.8 months. The PFS and OS were 5.2 and 14.5 months in the 44 patients on the phase II trial, with a 14% RR in BRCA1 (n=22) and 36% in BRCA2 (n=22). One of 30 patients responded to the combination therapy after progression on veliparib. Higher baseline PAR was associated with clinical benefit.

Conclusion

Safety and efficacy are encouraging with veliparib alone and in combination with carboplatin in BRCA-associated MBC. Lasting CRs were observed when the combination was administered first in the phase I trial. Further investigation of PAR level association with clinical outcomes is warranted.

Keywords: PARP inhibitors, veliparib, carboplatin, BRCA, advanced breast cancer

Introduction

Of the estimated 249,260 newly diagnosed breast cancers (BC) in the United States in 2016 (1), 5–10% will be associated with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (BRCA) (2). BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes that maintain genomic stability in part by participating in homologous recombination repair of double-stranded DNA breaks and gene conversion. Loss of BRCA function due to pathogenic mutations in BRCA causes homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) (3). Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), an essential nuclear enzyme highly expressed in tumor cells, is involved in recognition and repair of single-stranded breaks. By inhibiting the repair of single-stranded DNA breaks, double-stranded breaks are generated, causing selective cell death in BRCA deficient cells— a concept called synthetic lethality (4, 5). HRD can be exploited directly through the administration of DNA targeting platinum compounds, or indirectly, by inducing other mechanisms of DNA repair deficiency including the use of PARP inhibitors (PARPis) (4). There is evidence if PARPi activity in BRCA-associated BC (6–8). There is strong evidence that BRCA-associated ovarian cancer responds well to PARPis (9–11) with FDA approval in that setting (12). Studies focused on how to best utilize PARPis in metastatic BC (MBC) are still needed.

Preclinical evidence demonstrate that PARPis potentiate the effects of platinum in vivo (13–17) and emerging data suggest synergism between PARPis and platinum compounds in BRCA-associated BCs (18–20). Consequently, the California Cancer Consortium conducted companion clinical trials in patients with BRCA-associated MBC. The phase I trial was designed to define the maximum tolerated doses (MTD) of veliparib and carboplatin in combination and was initially designed to be a safety lead-in trial to a phase II randomized control trial comparing the combination of veliparib and carboplatin to single-agent veliparib. Efficacy data on single-agent veliparib was expected to be available (19, 20) by the time of this phase II study. However, due to the lack of published data for single-agent veliparib available at the completion of the phase I trial, the phase II design was changed to determine whether single-agent veliparib was active in either BRCA1- and/or BRCA2-associated MBC. The combination of veliparib and carboplatin was administered to those who progressed on single-agent veliparib. Planned correlative studies included the assessment of PAR levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) as a potential biomarker of clinical outcome in both the phase I and phase II studies.

Patients and Methods

Patients were enrolled into NCI#8264 (NCT01149083) through the California Cancer Consortium Data Coordinating Center—City of Hope— from 12 collaborating centers among 4 N01-funded consortia, including 10 sites that accrued patients for the phase I study. Women aged ≥18 years with measurable (RECIST version 1.1) germline BRCA-associated MBC were eligible for either the phase I or phase II trial. Patients with evaluable disease (non-measurable) were only eligible for the phase I trial. All patients must have progressed after at least one standard therapy for metastatic disease. There was no limit to the number of prior therapies allowed, however prior therapy with platinum (for MBC) or PARPis was prohibited. Grade ≤ 1 neuropathy and asymptomatic previously treated central nervous system metastasis were allowed. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Institutional Review Boards at all centers.

Phase I Trial–Study Design

The phase I study was based on a two-drug grid (Table 1) for dose escalation/de-escalation using the traditional rules for three patients per cohort: one DLT required expansion to six patients, two or more DLTs required de-escalation, and zero DLTs permitted escalation. With six patients, one DLT permitted escalation, and two DLTs required de-escalation and the MTD was defined as the highest dose tested with <33% of patients with DLT when at least six patients were treated at that dose. The level one doses were carboplatin AUC of 6 with veliparib 50 mg orally twice per day (BID), and escalations were restricted to veliparib. Veliparib was self-administered orally (50–200 mg, BID) and intravenous carboplatin was administered on day 1 of a 21-day cycle. Clinically responsive patients (stable disease or better) who were unable to tolerate continued carboplatin (after sequential dose reductions to an AUC of 2) were allowed to continue with single-agent veliparib only at the current dose for that patient. Toxicities were assessed using NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0.

Table 1.

Schema and dose level during the phase I and II parts of the trial

| Phase I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboplatin AUC 6 or 5 IV every 21 days and veliparib 50–200 mg BID | |||||

| Dose Level (L) | L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 |

| Number of patients | 7* | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Carboplatin AUC | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Veliparib mg BID | 50 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 200 |

| Phase II | |||||

| veliparib 400 mg BID/day, and upon progression, veliparib 150 mg BIDand carboplatin AUC 5 every 21 days | |||||

At L1, 1 patient was not evaluable for DLT evaluation due to rapidly emergent symptoms from brain metastasis and was replaced.

Phase I Trial–Procedures

Dose limiting toxicity (DLT) was any grade 3 non-hematological toxicity not reversible to grade ≤2 within 96 hours, or any grade 4 toxicity (excluding controllable nausea and vomiting). Patients unable to take 80% of the planned veliparib due to toxicity/tolerability were considered to have DLT, whereas patients unable to take 80% of planned veliparib due to non-compliance in the absence of toxicity/tolerability issues were replaced for the consideration of dose escalation decisions. The schema and dose levels are outlined in Table 1. Toxicities (other than lymphopenia, hyperglycemia, hypoalbuminemia, elevated alkaline phosphatase, low white blood cell count, and low hemoglobin) had to resolve to grade ≤ 1 before re-treatment. The carboplatin dose was reduced (each dose reduction was carried out by adjusting the AUC by 1) for neutropenic fever, following a second episode of grade ≥3 neutropenia (with or without growth factor administration, allowed as per ASCO guidelines), or grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia. Patients came off study if they could not tolerate at least an AUC of 2 of carboplatin (except as noted above for responding patients who continued on veliparib). Dose adjustment for veliparib was carried out by 50 mg per dose reductions to no less than 50 mg BID.

Phase I Trial–End Points

The phase I primary endpoint was to define DLTs and the MTD for the combination of veliparib and carboplatin. Secondary endpoints were confirmed response rates (RR): confirmed complete (CR) or partial response (PR) by RECIST, clinical benefit (CB, lack of progression within 24 weeks of study enrollment), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS).

Phase II Trial- Study Design

As noted above, the lack of sufficient evidence for activity of single-agent veliparib in BRCA1- or BRCA2-associated MBC caused reconsideration of the original phase II trial design to compare the combination of carboplatin and veliparib at the MTD against veliparib at the single agent MTD (400 mg BID) (NCT00892736). After thorough discussions among the collaborating institutions and the Cancer Therapy and Evaluation Program (CTEP) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) the trial design was amended to assess the efficacy of single-agent veliparib in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with MBC, with those progressing on single-agent veliparib treated with the combination of carboplatin and veliparib at the MTD based upon the acceptable toxicity and encouraging efficacy profile in our phase I trial. Hence, the phase II expansion/companion trial included parallel independent cohorts of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers each using a Simon Optimal two-stage (21).

Ten patients were initially accrued to each cohort (BRCA1 or BRCA2); two or more confirmed responses resulted in 12 additional patients being accrued to the respective cohort for a total of 22 patients per cohort, where six or more responders would indicate promising single agent activity. If both cohorts passed the interim analysis, a total of 44 patients were expected for the phase II trial. This design was based on 90% power to detect a response rate of 40% and a type I error of 10% for a discouraging response rate of 15% for each cohort. No early stopping rule was planned for patients receiving post-progression therapy of the veliparib and carboplatin combination. PFS, post-progression response to the doublet, and second post-PFS data were to be summarized.

Phase II Trial–Procedures

In the phase II trial, veliparib was started at 400 mg BID and was adjusted for grade ≥ 3 toxicities (doses were adjusted by 100 mg per dose per reduction, except when reducing the dose from 100 mg BID to the lowest dose of 50 mg BID) and could be held for ≤ 2 weeks due to toxicity (≤ 3 weeks for thrombocytopenia). Patients who progressed on single-agent veliparib were permitted to receive the combination with carboplatin at the previously determined MTD. Patients responding to the combination (stable disease or better) after cross-over were not allowed to return to single-agent veliparib as continuation therapy due to their previous progression with single agent therapy.

Phase II Trial–End Points

The phase II primary endpoint was the confirmed RR to single-agent veliparib, along with secondary objectives (CB, PFS, and OS for BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated MBC), and response to the combination of carboplatin and veliparib at the MTD upon progression.

Phase I and II Correlative Analyses

Correlatives included evaluation of veliparib pharmacokinetics when combined with carboplatin (phase I trial) and assessment of PBMC PAR levels (phase I and II). Peripheral blood samples were collected in Vacutainer Cell Preparation Tubes (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). In the phase I trial, samples were collected prior to and 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, and 6 hours after veliparib dosing on day 1 of cycle 1. In the phase II trial, samples were collected prior to, and 3 hours after, each cycle. Plasma concentrations of veliparib were quantified with an LC-MS assay (22). Pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters were extracted from the data by non-compartmental methods with PK Solutions 2.0™ (Summit Research Services, Montrose, CO).

PAR levels were quantified using fit-for-purpose sandwich immunoassay (IA) of denatured extracts of PBMCs (23–25). Previously validated NCI standard operating procedures (SOPs) were followed, including preparation and extraction of PBMCs to a normalized relative cell concentration, conduct of the ELISA-based validated assay, data analysis, assay quality control, and final data reporting (26).

Statistical Analysis

Tumors were evaluated by imaging at baseline and every third cycle. PFS (progression or death from any cause) and OS were defined from the start of treatment using RECIST criteria. PAR data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism for each IA plate by four parameter logistic nonlinear regression of the chemiluminescent relative light unit (RLU) values of an eight point calibrator curve, and applied to the unknown samples and quality control samples (24, 25). Each run was evaluated based on established assay performance specifications, and the calculated values obtained for three quality control xenograft tumor lysates run in quadruplicate on each plate. The effect of the baseline PAR level on outcome was analyzed, as was the relative change in PAR at 3 hours after the first dose of veliparib. Survival analyses (OS, PFS) were based on Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier methods (with log-rank test when appropriate). The natural cut-point of a median was used for the PAR analysis to avoid the inherent inflation of type I error associated with optimal cut-point selection. Multivariate Cox regression was used to evaluate if baseline PAR and relative change in PAR at 3 hours retained significance when including visceral dominant vs. bone/soft tissue sites, number and type of metastatic sites, hormone receptors, BRCA1 vs. BRCA2 status, age, and number of prior chemotherapy regimens for MBC. For categorical analysis, a two-sided Fisher’s Exact test was employed. Dose linearity for maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and AUC0-inf of veliparib was assessed through the power model on log-transformed data (27).

Results

Phase I–Summary of Patient Characteristics (see Table 2)

Table 2.

Patient characteristics (phase I & II)

| Patient Characteristics | Phase I | Phase II | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | BRCA1 Carriers | BRCA2 Carriers | All | |

| BRCA1 | 12 (43%) | 22 | – | – |

| BRCA2 | 15 (53%) | – | 22 | – |

| BRCA1&2 | 1 (4%) | – | – | – |

| Patients Treated | 28 | 22 | 22 | 44 |

| Median Age (Range) Yrs. | 45 (31–66) | 42 (28–68) | 44 (28–67) | 43 (28–68) |

| ER/PR + | 19 (68%) | 3 (14%) | 19 (86%) | 22 (50%) |

| HER2+ | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| # of prior chemo-regimens for MBC | 1 (0–5) | 1 (0–5) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–5) |

| ECOG PS | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) |

| Dominant Metastatic Site | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Bone with lung | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) | 6 (27%) | 8 (18%) |

| Bone with liver | 7 (25%) | 1 (4%) | 6 (27%) | 7 (16%) |

| Bone with nodes, other sites | 4 (14%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (9%) | 3 (7%) |

| Liver +/− lung | 7 (25%) | 3 (14%) | 2 (9%) | 6 (14%) |

| Lung | 4 (14%) | 9 (41%) | 2 (9%) | 12 (27%) |

| Nodes and/or soft tissue | 5 (18%) | 5 (24%) | 3 (14%) | 6 (14%) |

| Lung and brain | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Soft tissue with brain | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

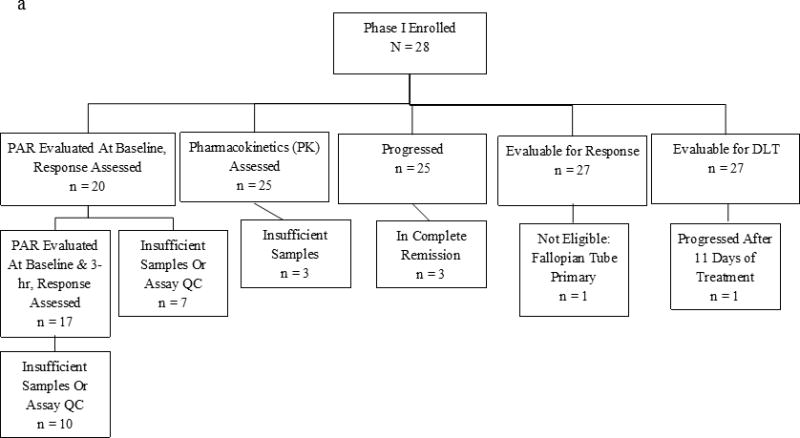

Between June 2010 and September 2012, 28 patients were enrolled in the phase I trial. All patients enrolled in phase I were evaluated for toxicities, and 27 were evaluable for efficacy. The median number of prior chemotherapy regimens for MBC was 1 (range, 0–5). None of the participants had received platinum in the adjuvant setting. BRCA2 patients in the phase I cohort were mostly ER/PR+ (94%, 15/16), while 36% (4/11) of BRCA1 patients were ER/PR+.

Phase I- MTD and Treatment-related Toxicities

DLTs at dose level 1, carboplatin AUC of 6 and veliparib 50 mg BID, were one grade 3 dehydration/pleural effusion/hyponatremia and one grade 4 thrombocytopenia. Given toxicities primarily attributed to carboplatin, the dose was reduced to AUC of 5, with future escalations restricted to veliparib. No intrapatient dose escalation occurred (it was permitted on the lowest dose level in the absence of grade 2 toxicity). In the six patients treated at dose level 2, carboplatin AUC of 5 and veliparib 50 mg BID, there was one grade 4 thrombocytopenia DLT. At dose level 5, carboplatin AUC of 5 and veliparib 200 mg BID, there were three DLTs (grade 3 thrombocytopenia; grade 4 thrombocytopenia; grade 3 thrombocytopenia and grade 4 ANC). Therefore, we expanded dose level 4, carboplatin AUC of 5 and veliparib 150 mg BID, to six patients. No DLTs were observed at this dose level, which was then defined as the MTD. Treatment-related toxicities observed during the phase I trial are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Treatment-related worst grade adverse events during phase I combination therapy, phase II single agent therapy, and during the phase II crossover combination therapy

| Toxicity Description | Patients, n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I Combination (n=28) |

Phase II Single Agent (n=44) |

Phase II Cross-over (n=30) |

|||||||

| Grade | |||||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Hematologic Toxicity | |||||||||

| Anemia | 14 (50%) | 7 (25%) | 2 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (7%) | 3 (10%) | |||

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 9 (32%) | 6 (21%) | 7 (16%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | |||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 9 (32%) | 7 (25%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (10%) | 8 (27%) | 2 (7%) | |

| Platelet count decreased | 7 (25%) | 8 (29%) | 7 (25%) | 2 (5%) | 5 (17%) | 5 (17%) | 3 (10%) | ||

| White blood cell decreased | 12 (43%) | 7 (25%) | 3 (7%) | 5 (17%) | 5 (17%) | ||||

| Non-hematologic Toxicity | |||||||||

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | ||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase increased | 2 (7%) | 1 (2%) | |||||||

| Hyperglycemia | 1 (4%) | 1 (2%) | |||||||

| Hyponatremia | 1 (4%) | ||||||||

| Dehydration | 1 (4%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (3%) | ||||||

| Abdominal pain | 1 (4%) | 3 (7%) | 1 (2%) | ||||||

| Anorexia | 1 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | ||||||

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 2 (5%) | ||||||||

| Nausea | 4 (14%) | 13 (30%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (7%) | |||||

| Pleural effusion | 1 (4%) | ||||||||

| Vomiting | 2 (7%) | 8 (18%) | |||||||

| Chills | 2 (5%) | ||||||||

| Dizziness | 1 (4%) | 1 (2%) | |||||||

| Fatigue | 12 (43%) | 2 (7%) | 11 (25%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | |||

| Chills | 2 (5%) | ||||||||

| Seizure | 2 (5%) | ||||||||

| Infusion related reaction | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | |||||||

While not part of DLT evaluation, during the first three cycles, five of the six patients treated at dose level 4 required delays or dose reductions subsequently. Carboplatin was stopped in five patients (due to toxicities, dose delay, or patient choice) who then continued on single-agent veliparib after a median of 9 (range, 4–16) cycles of combination therapy.

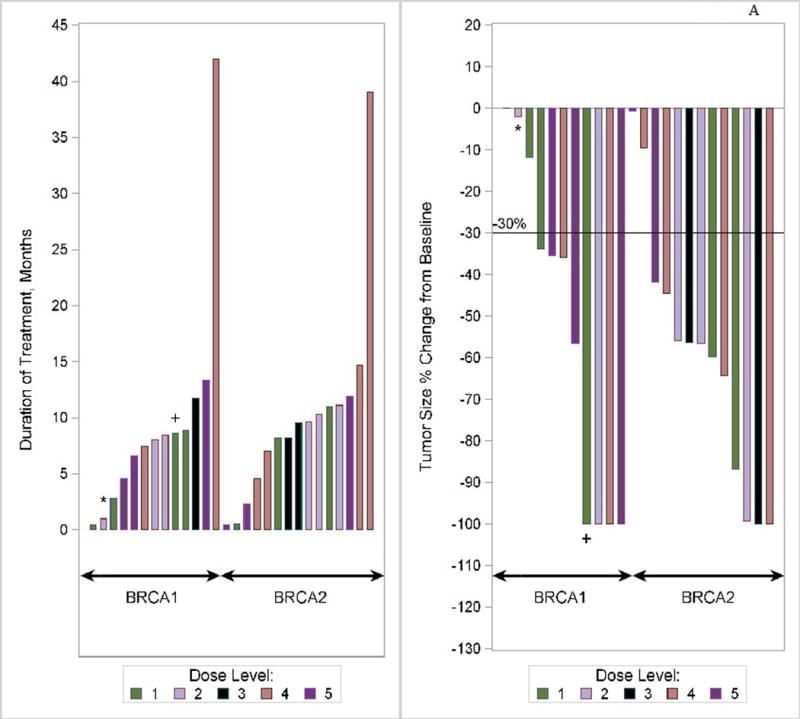

Phase I–Responses, PFS, and OS

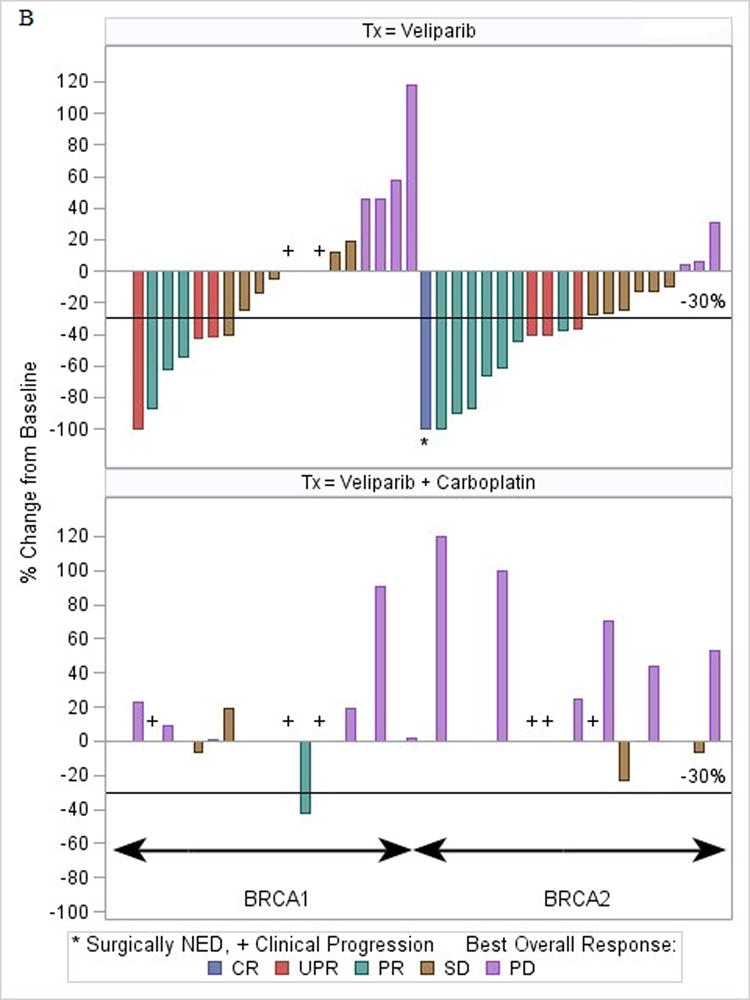

In the phase I trial, the median number of cycles was 9 (range, 1–54) and the overall RR was 56% (15/27). The response rate in the phase I trial was 53% (10/19) for ER/PR+ and 63% (5/8) for ER/PR− patients. Fifty percent (10/20) of patients with visceral disease responded, and 71% (5/7) without visceral disease responded. Fifty-nine percent (16/27) of patients experienced CB. As of July 2016, two patients are still in CR on veliparib single-agent continuation treatment (50 mg po BID) at 39+ and 42+ months since the start of therapy, and another patient chose to discontinue therapy after 13 months in CR (she received local regional radiation treatment while in CR to a previous metastatic site [axilla]) and remains in CR at 45+ months since the start of therapy (Fig 1a). With a median follow-up of alive phase I patients of 27.3 months, median PFS and OS (Fig 2a) were 8.7 months (95% CI, 7.3–10.6) and 18.8 months (95% CI, 15.0–23.2), respectively. There was no significant effect of BRCA1 vs. BRCA2, with a median PFS and OS of 8.5 and 21.8 months for BRCA1 patients, and 9.5 and 17.6 months for BRCA2 patients.

Figure 1.

(a) Waterfall plot for phase I study. *Patient was BRCA1 and BRCA2. +Patient was later discovered to have ineligible histology (fallopian tube). Note: three patients did not have tumor assessments to permit measurement of change (2 did not have assessments due to toxicity/hospitalization, and 1 did not have measureable disease). (b) Waterfall plot for phase II study (bottom plot: represents the patients (n = 30) who progressed on single-agent veliparib) Note: 5 patients in Phase II did not have tumor measurements due to early treatment failure due to toxicity.

Figure 2.

(a) Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in phase I patients (b) PFS and OS in phase II patients. The bottom plot represents patients who progressed on single-agent veliparib.

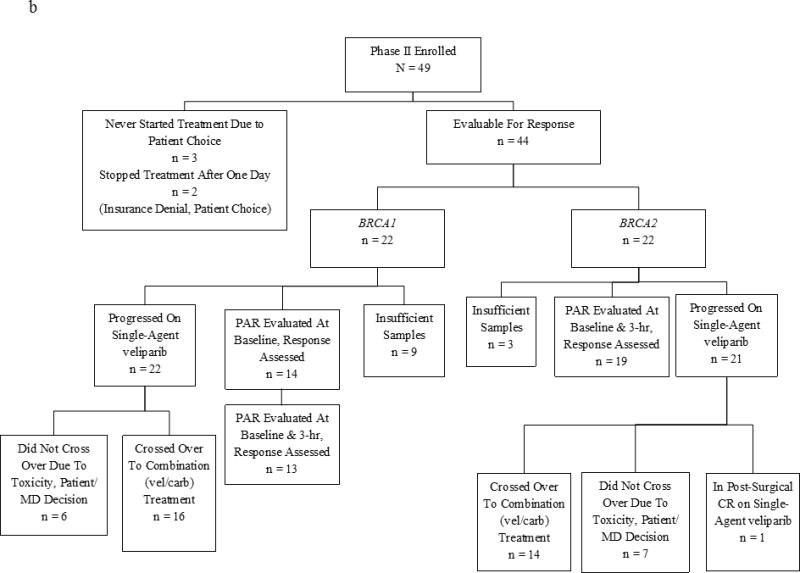

Phase II–Summary of Patient Characteristics (see Table 2)

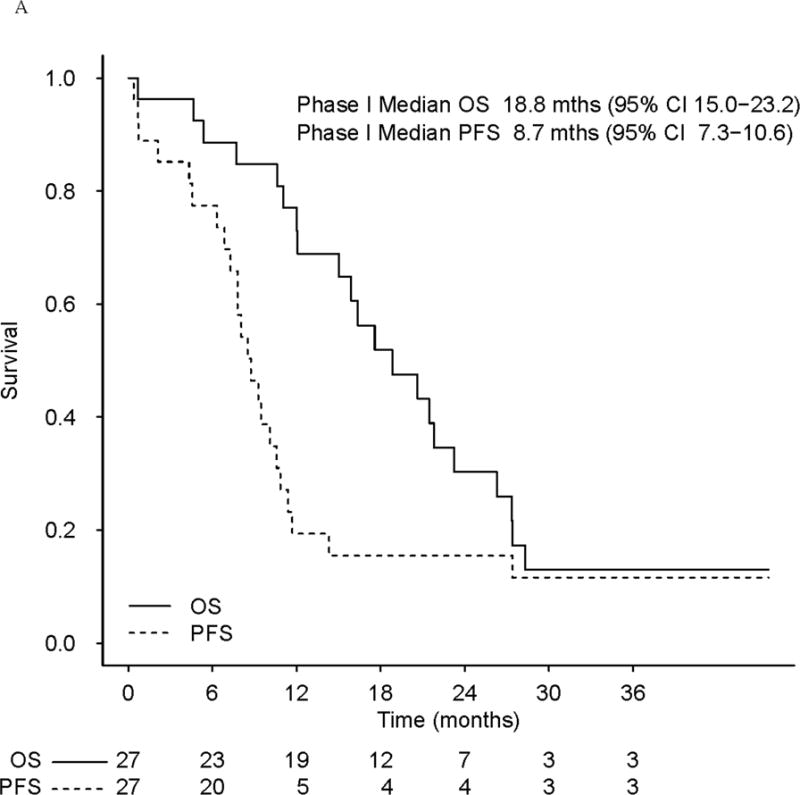

Between October 2012 and October 2014, 49 patients were enrolled in the phase II trial. Of these, 44 patients—equally distributed between BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers (Fig 3b)—were evaluable for both response and toxicities. Five non-evaluable subjects were replaced in consultation with NCI CTEP. None of the participants had received platinum in the adjuvant setting. The median number of prior chemotherapy regimens for MBC was 1 (range, 0–5).

Figure 3.

(a) Phase I Study Consort Diagram (b) Phase II Study Consort Diagram

Phase II–Toxicities

Phase II trial toxicities are also depicted in Table 3. Seventy-five percent of patients tolerated the initial dose of veliparib, with 25% requiring dose adjustments due primarily to nausea/vomiting and fatigue (median dose 400 mg [range, 100–400] BID). There were no unexpected toxicities noted in the 30 patients who—upon progression—received both veliparib and carboplatin at the MTD established in the phase I trial (see Table 3).

Phase II–Responses, PFS, and OS

In the BRCA1 cohort, we observed PR in three and CB in two patients with a RR of 14% and CB rate of 23%. In the BRCA2 cohort, eight patients achieved PRs (one of whom underwent resection of a liver metastasis with a post-resection CR, and continues with single-agent veliparib at 27.5+ months), and six patients had CB, with a RR of 36% and CB rate of 64% (Fig 1b and Supplemental Table 1). The CB was statistically higher (64% vs. 23%; P < .02, 2-sided Fisher’s exact test) for BRCA2 vs. BRCA1 patients, while the response rate difference (36% vs. 14%; P=0.16, 2-sided Fisher’s exact test) was not statistically significant. The RR was 36% in the ER/PR+ patients, most of whom were BRCA2 carriers (Table 2), and 14% in the ER/PR− patients. Of 35 patients with visceral disease eight responded (23%) and 33% (3/9) without visceral disease responded.

Median PFS was longer for BRCA2 vs. BRCA1 patients (6.6 vs. 3.6 months; P < .05) but there was no statistical difference in OS (14.7 vs. 11.8 months; P = .16) or RR (36% vs. 14%; P = .16). Sixty eight percent (30/44) of phase II patients progressed and crossed over to the combination of veliparib and carboplatin at the previously defined MTD: 16 were BRCA1 and 14 were BRCA2 carriers. Only one BRCA1 patient had a PR (RR = 1/30) after cross-over, and the time from the start of combination therapy to second progression for her was 15.3 months. Of the remaining BRCA1 patients, none were documented to be progression-free at six months, and the median time to progression was under two months. Of the BRCA2 patients (n = 22), 14 crossed over to the combination after progression, with one patient who progressed at six months, three who progressed between two and five months, one who came off for toxicity at three and a half months, and nine who progressed in two months or less.

Among all 44 phase II evaluable patients, the median time on single-agent veliparib was 4.1 months (95% CI, 3.0–6.0) and PFS 5.2 months (95% CI, 4.0–6.4; Fig 2b), with a median OS of 14.5 months (95% CI, 11.8–15.9; Fig 2b).

The median PFS of the 30 patients starting combination therapy after progressing on single-agent veliparib was 1.8 months (95% CI, 1.4–2.3), with a median of 1.8 months for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 patients.

Thirteen patients stopped single-agent veliparib but did not proceed with the crossover treatment either because they came off study due to toxicity (n = 5, mostly due to fatigue), chose to discontinue therapy (n = 1), or were recommended or elected other chemotherapy (n = 7). The median follow-up of currently surviving phase II patients is 10.3 months.

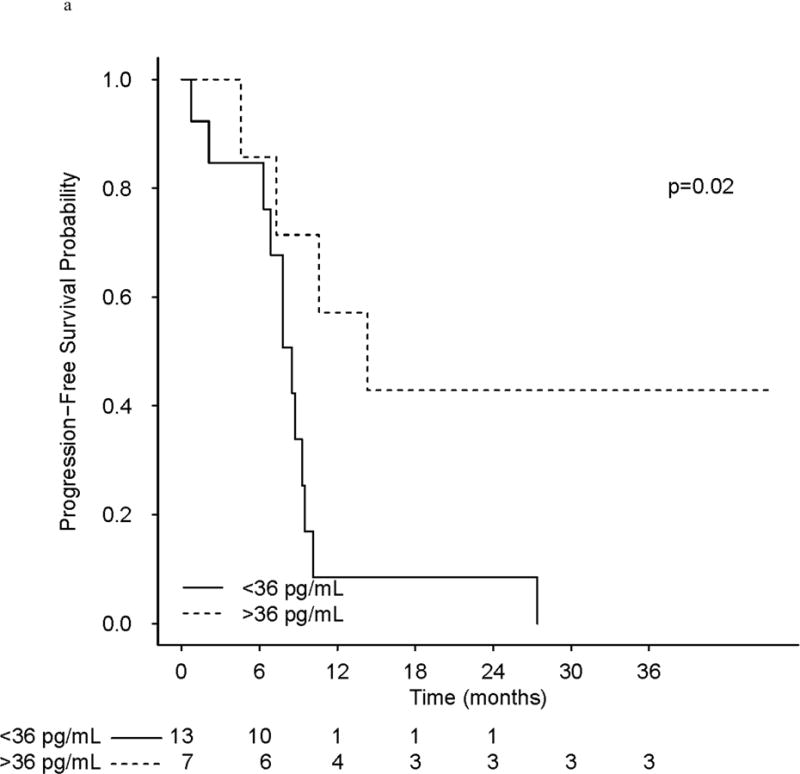

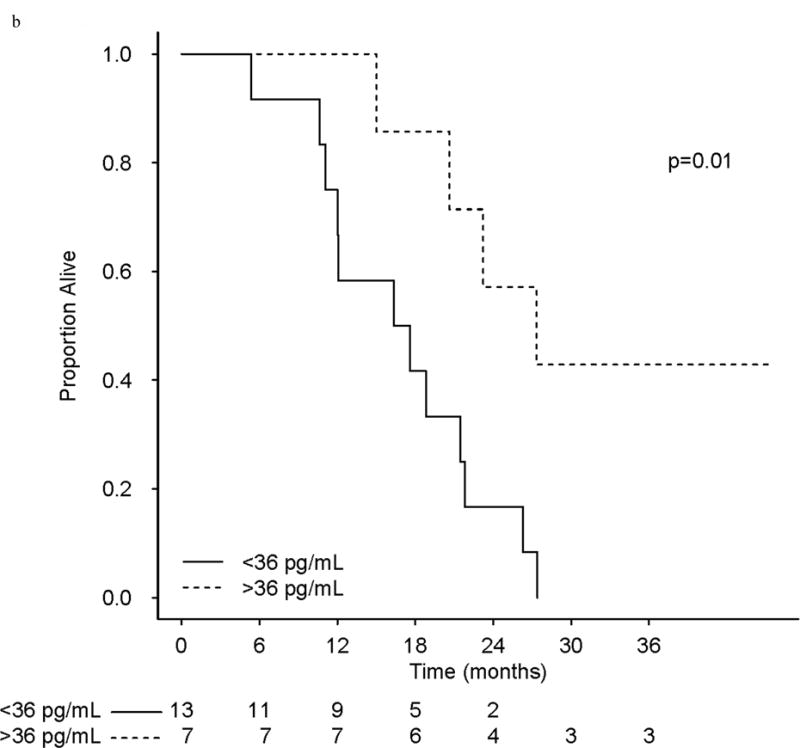

PAR and PK Analysis

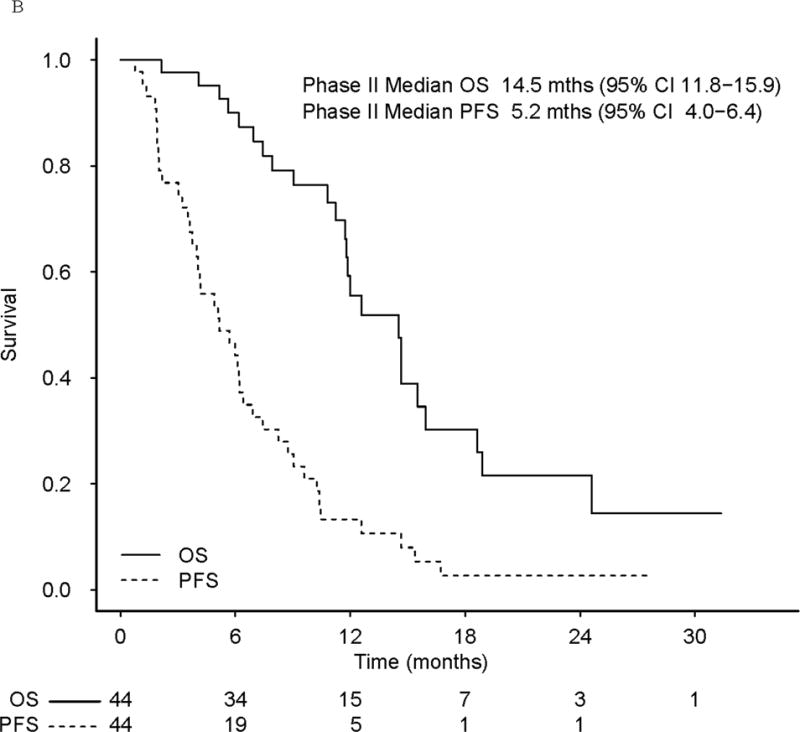

There were 71 (27 phase I and 44 phase II) patients included in analyses, and 53 of the 71 had assessable baseline PAR levels (phase I [n = 20]; phase II [n = 33]). The median baseline PAR level for all 53 patients was 36.0 pg/mL (range, 10.4–193.0 pg/mL). Setting 36.0 pg/mL as the cut-point for baseline analysis, PFS was longer in phase I patients with “high” (>36 pg/mL) levels of baseline PAR (HR, 0.26; 0.08–0.87; P = .02), as was OS (HR, 0.25; 0.08–0.80; P = .05; Fig 4).

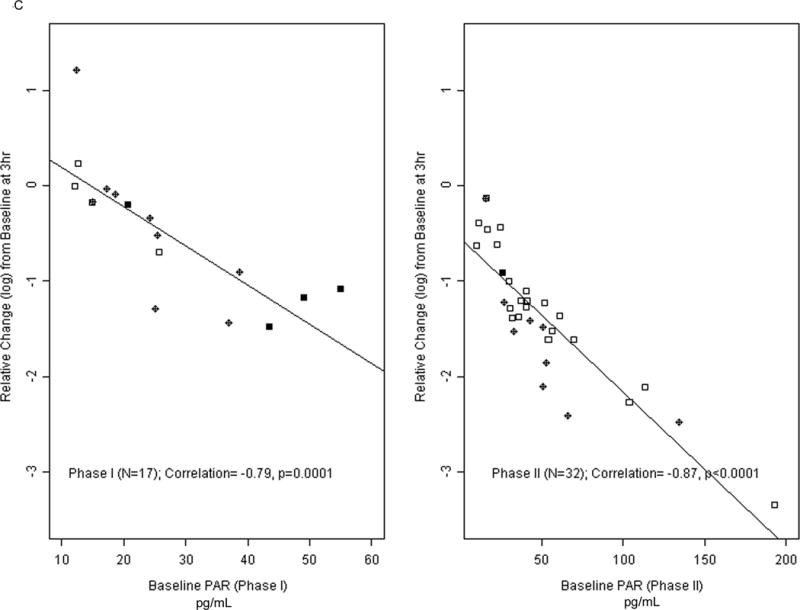

Figure 4.

(a) Progression-Free Survival in phase I treated with veliparib and carboplatin patients as a function of PAR levels pre-treatment. (b) Overall survival in patients on the phase I study as a function of PAR levels. (c) Relative Change from PAR baselines levels (pg/mL) in phase I/II patients.

No statistically significant effect on PFS or OS of baseline PAR alone was observed in the phase II patients, either based on the cut-off, or examining the baseline PAR value as a continuous variable. However, in an exploratory analysis, the five patients (of those with baseline PAR in phase II [n = 33]) with the lowest baseline PAR values (< 22 pg/mL) had both inferior PFS (median 3.2 vs. 5.8 months; P < 0.02), and inferior OS (median 6.9 vs. 15.5 months; P < 0.001).

Patients in both phase I and phase II had significantly reduced PAR levels after initiating treatment (Fig 4). Phase I patients with baseline and 3 hour samples (n = 17) had a 28% reduction in median PAR levels (Wilcoxon, P = .01). Phase II patients had a 74% reduction (n = 32, P < .001), with 71% reduction for BRCA2 patients (n = 19) and 75% reduction for BRCA1 patients (n = 13).

In exploratory analysis the difference in reduction in PAR levels between the phase I and phase II patients was significant (P < .001), likely due to the higher veliparib dose given to phase II patients.

The higher the baseline PAR levels, the greater the observed reduction (percent and reduction on a log-scale) in PAR at 3 hours. The correlation between baseline PAR and reduction at 3 hours was 79% for phase I patients. For phase I patients who had > 50% reduction of PAR at 3 hours, the median PFS was 14.3 months (95% CI, 7.8–NR) vs. 8.7 months (95% CI, 7.8–9.5) for patients with ≤ 50% reduction in PAR (P = .04). In addition, phase I patients with > 50% reduction in PAR levels had a median OS of 27.3 months vs. 17.6 months for patients with ≤ 50% reduction (P < .02).

The correlation between baseline PAR and reduction at 3 hours was 87% for phase II patients. A 50% reduction in PAR levels was associated with a median OS of 15.9 months vs. 9.0 months for patients who had less reduction (P < .01), although the difference in PFS was statistically marginal (6.0 vs. 4.0 months, P = .07).

While there are limited patient numbers (n = 20) with baseline PAR values assessed in the phase I study, multivariate analysis confirmed the importance of baseline PAR (>36.0 pg/mL) for phase I patients: when adjusting for age, visceral dominant vs. bone/soft tissue site, number and type of metastatic sites, hormone receptors, BRCA1 vs. BRCA2 status, and number of prior chemotherapy regimens for MBC, a significant benefit of elevated baseline PAR levels (>36 pg/mL) was maintained for both PFS (HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.07–0.99), and OS (HR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.04–0.84). For the phase II patients, as with univariate, baseline PAR (>36.0 pg/mL), differences in PFS (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.35–2.09), and for OS (HR, 0.60 95% CI, 0.20–1.75) were not significant in multivariate analysis. As the baseline value was highly correlated with a subsequent reduction in PAR at 3–4hrs after initial treatment, as expected, multivariate analysis showed a significant impact of a 50% reduction in baseline PAR levels at 3–4 hours (data not shown). However, the baseline measurement was our focus on the exploratory multivariate analysis due to its potential as a biomarker to help select patients likely to respond to PARPis.

Pharmacokinetics

Veliparib pharmacokinetic data were available for 25 phase I patients. Dose linearity assessments for maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) resulted in a coefficient of 1.12 (95% CI, 0.869–1.38; 90% CI, 0.913–1.33) and for AUC (AUC0-inf) resulted in a coefficient of 1.25 (95% CI, 0.962–1.53; 90% CI, 1.011–1.48). Thus, dose-proportionality of veliparib across the dose range was seen (Supplemental Table 2). Higher Cmax, had a trend for improved PFS (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.19–1.11, P = 0.08) and OS (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.17–1.08, P = 0.07) in this phase I study (n = 24, 1 ineligible patient excluded from outcome evaluation) and both trends persisted in multivariate analysis (data not shown).

Discussion

Despite the efficacy of novel therapies, patients with MBC are considered incurable (28–30). Tumors that exhibit genomic instability such as HRD, especially those associated with germline BRCA mutations and potentially with other DNA-repair impediments, are promising therapeutic targets of PARPis, regardless of histologic subtype (31). While PARPis show single agent activity and likely disrupt DNA repair through multiple mechanisms, further potentiation of synthetic lethality by combining PARPis with platinum agents in patients with BRCA-associated cancers is an attractive concept (16) that has shown encouraging results in preliminary clinical studies (9, 32, 33).

We established the MTDs, when combined, for the PARPi veliparib (150 mg BID) and carboplatin (AUC of 5), in our phase I trial. However, cytopenias leading to protocol-specified delays or dose-reduction were observed in 75% of the phase I patients during cycles 1–3. In a phase I/Ib dose escalation study of the PARPi olaparib, grade 3/4 toxicities were predominantly cytopenias when olaparib (400 mg, BID, days 1–7) was given with carboplatin (AUC of 5) (34). A > 50% decrease in PAR levels was seen in 19 of 30 patients treated with olaparib, but did not show correlation with PFS (34). In contrast, we demonstrated that baseline levels and amount of reduction in PAR levels after treatment with veliparib is associated with improved outcome among women with BRCA-associated MBC, with higher baseline levels and/or greater reduction in PAR suggestive of improved OS. The differences between the two trials might be related to variable patient populations; additional confirmatory assessments are needed. Veliparib PK parameters observed in this study are in line with previous reports (35). Our phase II parallel BRCA1 and BRCA2 cohort study conducted in patients accrued among multiple NCI-contracted Comprehensive Cancer Centers allowed us to test the activity of single-agent veliparib in the largest cohort of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated MBC patients, to-date. We established the single agent response rates and confirmed the toxicities and feasibility of veliparib (400 mg BID) dosing observed in smaller BRCA-associated MBC cohorts (17, 20). We observed a statistically higher CB and median PFS favoring the BRCA2-associated MBC cohort and a non-statistically significant higher RR. This exploratory observation is hypothesis generating, and combined with the differences in hormonal status, suggests the possibility of important biologic and clinical differences between BRCA1 and BRCA2 MBC patient populations.

In an unplanned analysis, we observed greater CB, overall RR, PR, and CR rates in patients treated with the upfront combination (phase I) vs. single-agent veliparib, even when including the time on the permitted cross-over to the combination for patients in the phase II trial who started with single-agent veliparib. While these are two distinct patient populations treated in a non-randomized fashion, we hypothesize that the outcomes of veliparib and carboplatin combination therapy are superior to single-agent veliparib followed by post-progression combination treatment due to the ability of the tumor to up-regulate other repair mechanisms during the single agent treatment, thereby reducing the potential synergy when delaying the combination. That is, the tumors in patients who progressed on single-agent veliparib may develop distinct mechanisms of resistance that diminish the efficacy of combination therapy.

The limited sample size of our study populations, lack of randomization, and absence of a single-agent carboplatin arm in the phase II study make it difficult to clearly define the benefits of veliparib and carboplatin in the combination therapy. As noted in the methods section, the original phase II study design included randomization, but was modified in consultation with CTEP to a post-progression design due to the need for more definitive single-agent veliparib efficacy data. Thus there is still a need to define whether single-agent platinum could be as effective as combinations with PARPis in patients with BRCA-associated MBC.

A randomized prospective trial in triple negative and/or BRCA-associated MBC is currently comparing cisplatin with or without veliparib (NCT02595905). Direct comparisons of other PARPis and platinum agents are unlikely to emerge soon, since none of the currently ongoing phase III randomized trials compare individual PARPis (olaparib –NCT02000622; or niraparib –NCT01905592) against platinum agents. Similar difficulties exist in defining whether veliparib is a significant contributor to carboplatin in the neoadjuvant setting, as observed in the I-SPY 2 trial which included predominantly non BRCA-mutation carriers with triple negative BC (36).

There is limited data on BRCA-associated MBC patients treated with platinum agents, though the response rate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy for triple negative BC can be as high as 46%–61% (37, 38). We observed durable CRs lasting more than three years in three phase I patients treated with combination veliparib and carboplatin therapy. Although it is possible that the observed CRs were primarily due to the platinum component, no CRs were reported in a smaller study (n = 11 BRCA patients) that evaluated cisplatin or carboplatin alone, and PFS or OS were not better between the BRCA-carriers vs. non-carriers, with six long-term responders without BRCA mutations described (32). The evidence from the germline BRCA-mutation carrier MBC population cohort in our study suggests that combined therapy may provide more potent synthetic lethality and/or help overcome mechanisms of resistance, leading to better outcomes (39, 40). As a low RR in the post-progression combination therapy component was not anticipated in the phase II trial design, we did not consider an early stopping point.

Our observations about PAR level/response are promising, but not all centers were successful at following the SOP for collection and initial processing of correlative samples. Procedural training at the NCI for laboratory personnel and the close adherence to the analysis SOP at the study center were likely key to successful execution of the protocol. The potential implications of either baseline or degree of reduction of PAR levels observed during the first treatment cycles are worthy of further investigation, ideally in the context of ongoing phase III trials. While the median baseline PAR level was selected as the cut-point in this study, the intention is to motivate larger studies to examine the role of baseline PAR to possibly help select patients for PAR-directed therapy. Ongoing genomic analyses of archival tumor tissues may shed additional light on characteristics that predict CB, and in particular of exceptional responders (41). Further assessments of PARPis and combinations of agents that disrupt DNA repair—whether BRCA or other germline or somatic mutation associated—are needed, and are ongoing in MBC and other malignancies (42).

In conclusion, while our data demonstrate single agent activity for veliparib in the context of BRCA-associated MBC, initial therapy with combined veliparib and platinum-based chemotherapy (with continuation single-agent veliparib therapy for responders with cumulative toxicity from platinum) may be the favored strategy. Intriguing data from a recent study of olaparib and carboplatin indicate sequence specific effects on pharmacokinetics, suggesting that carboplatin should be administered prior to olaparib (43). The addition of veliparib to a combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel is also promising. A randomized phase II trial (BROCADE, NCT01506609) conducted in BRCA-carriers with advanced breast cancer carboplatin, paclitaxel, and veliparib vs. placebo resulted in 77.8% vs. 61.3% overall response rate (18). An ongoing phase III randomized prospective trial (BROCADE 3, NCT 02163694) in BRCA-associated MBC comparing carboplatin and paclitaxel with veliparib vs. placebo, with cross-over to veliparib for patients on placebo upon progression, may confirm our hypothesis of the benefit of using combinations with veliparib first, and may lead to availability of a PARPi for appropriate patients. Our work also suggests that PAR levels in PBMCs, which are readily accessible compared to tumor biopsies, may predict the benefits of PARPi therapy and further evaluation of this biomarker is important in the context of both PARPi and DNA damaging agents.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

BRCA1- and BRCA2- (BRCA)-associated tumors respond to both platinum compounds and poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymerase inhibitors (PARPis). Potential synergism for carboplatin and the PARPi veliparib was demonstrated in preclinical studies. In patients with BRCA-associated metastatic breast cancer (MBC) the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and safety of the combination of veliparib and carboplatin was demonstrated, as were durable—including complete—responses. In a companion phase II trial, veliparib was demonstrated to be active as a single agent in both BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated MBC patients. Post-progression treatment with carboplatin and veliparib at the MTD for the combination yielded minimal benefit. The optimal combination of drugs with PARPis, and/or sequence of administration need prospective studies. Higher baseline PAR levels, as measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, were associated with better clinical outcomes and may identify patients who could benefit from treatment with PARPis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Timothy Synold, Timothy O’Connor, and Brian Kiesel for their contributions to this work. We also thank Stella, Khoo, Kim Robinson, and Tracy Sulkin for facilitating data collection and quality assurance on this multi-site study. We thank the patients who participated and all of the investigators, study nurses, and site staff for their support.

Funding Support

Veliparib was provided under a Cooperative Research Agreement (CRADA) between the NCI and Abbvie. This study was supported by R21CA137684 (J Weitzel), N01CM62209, P30CA33572, UM1CA186690, and P30CA47904. With NO1-CM-62209 funding, the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) was involved in approval of trial design and submission for publication. Research reported in this publication includes work performed in the Pathology Core supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA033572. PAR assay training and reagents were supported by NCI Contract No HHSN261200800001E and R21CA137684. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors

Conception and design: JNW, GS, PHF, EMN, DRG

Collection and assembly of data: AAG, AH, BKA, CXM, GS, JNW, HAH, HKC, JHB, JM, JH, LRVT, KFG, LVC, LTV, MPG, PHF, RN, SS, TC, TJM

Data analysis and interpretations: AAG, BKA, CR, GS, JNW, JHB, JH, JAS, KFG, MPG, PHF

Manuscript Writing and Final approval of Manuscript: all authors

Financial Support: JNW, EMN

Administrative Support: SS, LRVT

Provision of Study Materials: GS, JNW, JAS

All authors contributed to the intellectual content of the report and provided critical review and final approval of the submitted manuscript. All authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data reported and the fidelity of the studies to the protocols.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Easton DF, Pharoah PDP, Antoniou AC, Tischkowitz M, Tavtigian SV, Nathanson KL, et al. Gene-Panel Sequencing and the Prediction of Breast-Cancer Risk. New Engl J Med. 2015;372(23):2243–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1501341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donovan PJ, Livingston DM. BRCA1 and BRCA2: breast/ovarian cancer susceptibility gene products and participants in DNA double-strand break repair. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(6):961–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helleday T. Homologous recombination in cancer development, treatment and development of drug resistance. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(6):955–60. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434(7035):913–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek S, Audeh MW, Weitzel JN, et al. Oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9737):235–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livraghi L, Garber JE. PARP inhibitors in the management of breast cancer: current data and future prospects. BMC medicine. 2015;13:188. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0425-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karginova O, Siegel MB, Van Swearingen AE, Deal AM, Adamo B, Sambade MJ, et al. Efficacy of Carboplatin Alone and in Combination with ABT888 in Intracranial Murine Models of BRCA-Mutated and BRCA-Wild-Type Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(4):920–30. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2154–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman RL, Sill MW, Bell-McGuinn K, Aghajanian C, Gray HJ, Tewari KS, et al. A phase II evaluation of the potent, highly selective PARP inhibitor veliparib in the treatment of persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer in patients who carry a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation - An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(3):386–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Audeh MW, Carmichael J, Penson RT, Friedlander M, Powell B, Bell-McGuinn KM, et al. Oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9737):245–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60893-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim G, Ison G, McKee AE, Zhang H, Tang S, Gwise T, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Olaparib Monotherapy in Patients with Deleterious Germline BRCA-Mutated Advanced Ovarian Cancer Treated with Three or More Lines of Chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(19):4257–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balmana J, Tung NM, Isakoff SJ, Grana B, Ryan PD, Saura C, et al. Phase I trial of olaparib in combination with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with advanced breast, ovarian and other solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(8):1656–63. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Ashworth A. Synthetic lethality and cancer therapy: lessons learned from the development of PARP inhibitors. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:455–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050913-022545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen Y, Aoyagi-Scharber M, Wang B. Trapping Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;353(3):446–57. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.222448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark CC, Weitzel JN, O’Connor TR. Enhancement of Synthetic Lethality via Combinations of ABT-888, a PARP Inhibitor, and Carboplatin In Vitro and In Vivo Using BRCA1 and BRCA2 Isogenic Models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11(9):1948–58. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wesolowski R, Zhao M, Geyer SM, Mrozek MBLE, Layman RM, Macrae EM, et al. Phase I trial of the PARP inhibitor veliparib (V) in combination with carboplatin (C) in metastatic breast cancer (MBC) J Clin Oncol. 2014;(suppl) abstr 1074. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han H, Dieras V, Robson M, Palacova M, Marcom P, Jager A, editors. Efficacy and tolerability of veliparib in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel vs. placebo in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations in metastatic breast cancer. A randomized phase 2 study. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; 2016; December 6–10, 2016; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puhalla S, Beumer JH, Pahuja S, Appleman LJ, Tawbi HA-H, Stoller RG, et al. Final results of a phase 1 study of single-agent veliparib (V) in patients (pts) with either BRCA1/2-mutated cancer (BRCA+), platinum-refractory ovarian, or basal-like breast cancer (BRCA-wt) J Clin Oncol. 2014;(suppl) abstr 2570. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pahuja S, Beumer JH, Appleman LJ, Tawbi HA-H, Stoller RG, Lee JJ, et al. Outcome of BRCA 1/2-Mutated (BRCA+) and triple-negative, BRCA wild type (BRCA-wt) breast cancer patients in a phase I study of single-agent veliparib (V) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 26) abstr 135. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989 Mar;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parise RA, Shawaqfeh M, Egorin MJ, Beumer JH. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometric assay for the quantitation in human plasma of ABT-888, an orally available, small molecule inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;872(1–2):141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinders RJ, Hollingshead M, Khin S, Rubinstein L, Tomaszewski JE, Doroshow JH, et al. Preclinical modeling of a phase 0 clinical trial: qualification of a pharmacodynamic assay of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumor biopsies of mouse xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(21):6877–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji J, Kinders RJ, Zhang Y, Rubinstein L, Kummar S, Parchment RE, et al. Modeling pharmacodynamic response to the poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase inhibitor ABT-888 in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PloS one. 2011;6(10):e26152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kummar S, Kinders R, Gutierrez ME, Rubinstein L, Parchment RE, Phillips LR, et al. Phase 0 Clinical Trial of the Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitor ABT-888 in Patients With Advanced Malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2705–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.NCI Division of Cancer Treatment & Diagnosis. Validated Assays, Specimen Handling Procedures and Reagent Sources for Poly-Adenosyl Ribose (PAR) Immunoassay. Bethesda, MD: NCI Division of Cancer Treatment & Diagnosis; [updated 03/24/201505/26/2016)]; Available from: http://dctd.cancer.gov/ResearchResources/biomarkers/PolyAdenosylRibose.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith BP, Vandenhende FR, DeSante KA, Farid NA, Welch PA, Callaghan JT, et al. Confidence interval criteria for assessment of dose proportionality. Pharm Res. 2000;17(10):1278–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1026451721686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta RS, Barlow WE, Albain KS, Vandenberg TA, Dakhil SR, Tirumali NR, et al. Combination anastrozole and fulvestrant in metastatic breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):435–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendes D, Alves C, Afonso N, Cardoso F, Passos-Coelho JL, Costa L, et al. The benefit of HER2-targeted therapies on overall survival of patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer–a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:140. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurvitz S, Mead M. Triple-negative breast cancer: advancements in characterization and treatment approach. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;28(1):59–69. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, Miranda S, Mossop H, Perez-Lopez R, et al. DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Eng J Med. 2015;373(18):1697–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isakoff SJ, Mayer EL, He L, Traina TA, Carey LA, Krag KJ, et al. TBCRC009: A Multicenter Phase II Clinical Trial of Platinum Monotherapy With Biomarker Assessment in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1902–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.6660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murai J, Huang S-YN, Renaud A, Zhang Y, Ji J, Takeda S, et al. Stereospecific PARP Trapping by BMN 673 and Comparison with Olaparib and Rucaparib. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2014;13(2):433–43. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JM, Hays JL, Annunziata CM, Noonan AM, Minasian L, Zujewski JA, et al. Phase I/Ib study of olaparib and carboplatin in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation-associated breast or ovarian cancer with biomarker analyses. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju089. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salem AH, Giranda VL, Mostafa NM. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of veliparib (ABT-888) in patients with non-hematologic malignancies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53(5):479–88. doi: 10.1007/s40262-013-0130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rugo HS, Olopade OI, DeMichele A, Yau C, van ’t Veer LJ, Buxton MB, et al. Adaptive Randomization of Veliparib-Carboplatin Treatment in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(1):23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Byrski T, Huzarski T, Dent R, Marczyk E, Jasiowka M, Gronwald J, et al. Pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant cisplatin in BRCA1-positive breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147(2):401–5. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arun B, Bayraktar S, Liu DD, Gutierrez Barrera AM, Atchley D, Pusztai L, et al. Response to neoadjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer in BRCA mutation carriers and noncarriers: a single-institution experience. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(28):3739–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swisher EM, Sakai W, Karlan BY, Wurz K, Urban N, Taniguchi T. Secondary BRCA1 Mutations in BRCA1-Mutated Ovarian Carcinomas with Platinum Resistance. Cancer Res. 2008;68(8):2581–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakai W, Swisher EM, Karlan BY, Agarwal MK, Higgins J, Friedman C, et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of cisplatin resistance in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature. 2008;451(7182):1116–20. doi: 10.1038/nature06633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodler ET, Kurland BF, Griffin M, Gralow JR, Porter P, Yeh RF, et al. Phase I Study of Veliparib (ABT-888) Combined with Cisplatin and Vinorelbine in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and/or BRCA Mutation-Associated Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(12):2855–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dhawan M, Ryan CJ, Ashworth A. DNA Repair Deficiency Is Common in Advanced Prostate Cancer: New Therapeutic Opportunities. Oncologist. 2016;21(8):940–5. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JM, Peer CJ, Yu M, Amable L, Gordon N, Annunziata CM, et al. Sequence-specific pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic phase I/Ib study of olaparib tablets and carboplatin in women’s cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016:1–10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.