Abstract

Background

Previous studies rarely evaluated the associations between vitamin D binding protein and free vitamin D with colorectal cancer (CRC) risk. We assessed these biomarkers and total 25-hydroxyvitamin D in relation to CRC risk in a sample of African Americans.

Methods

Cases comprised 224 African American participants of the Southern Community Cohort Study diagnosed with incident CRC. Controls (N=440) were selected through incidence density sampling and matched to cases on age, sex, and race. Conditional logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between biomarker levels and CRC risk.

Results

Vitamin D was inversely associated with CRC risk where the OR per-standard deviation increase in total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D were 0.82 (95%CI: 0.66–1.02) and 0.82 (95%CI: 0.66–1.01), respectively. Associations were most apparent among cases diagnosed >3 years after blood draw: ORs for the highest tertile versus the lowest were 0.69 (95%CI: 0.21–0.93) for total 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 0.71 (95%CI: 0.53–0.97) for free 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Inverse associations were seen in strata defined by sex, BMI, and anatomic site, although not all findings were statistically significant. Vitamin D binding protein was not associated with CRC risk.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D may be inversely associated with CRC risk among African Americans.

Impact

These findings highlight a potential role for vitamin D in CRC prevention in African Americans.

Keywords: vitamin D, African Americans, colon cancer, rectal cancer, vitamin D binding protein

Introduction

Previous meta-analyses of prospective epidemiologic studies report an inverse association between total circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D, the clinical measure of vitamin D status, and colorectal cancer risk (1,2). Most previous studies have focused exclusively on total 25-hydroxyvitamin D or vitamin D3 in association with cancer risk, potentially missing important associations between bioavailable 25-hydroxyvitamin D, free 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk. Bioavailable 25-hydroxyvitamin D is defined as the portion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D not bound by vitamin D binding protein and it accounts for approximately 10–15% of total circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Free 25-hydroxyvitamin D constitutes less than 1% of total 25-hydroxyvitamin D in circulation and is completely unbound from albumin and vitamin D binding protein (3–5). Bioavailable and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D are hypothesized to have higher biologic potential to act on cells than bound 25-hydroxyvitamin D (4,6,7). However, recent studies have found mixed results for the associations between these biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk. One study reports strong inverse associations between colorectal cancer risk and free and bioavailable 25-hydroxyvitamin D (8), whereas other studies find null or modest positive associations between the biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk (9–11). Additionally, no study of bioavailable or free 25-hydroxyvitamin D has been conducted in a sample with large numbers of African Americans, whose total 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels tend to be substantially lower than in people of European descent. Herein, we evaluate the associations of circulating vitamin D binding protein, total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and colorectal cancer risk in a study sample of African Americans.

Materials and Methods

Study population

Data for current analysis arise from a nested case-control study within the Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS), a previously-described prospective cohort study designed to investigate health disparities (12,13). The SCCS enrolled over 85,000 participants from 2002–2009 from 12 states in the southeastern US. Eligible participants were age 40 to 79 at enrollment, English-speaking, and provided a blood sample to the study for biomarker measurement. Participants provided information on lifestyle factors, demographics and personal medical history, primarily via in-person interviews. Cases for the current study were identified through linkages with state cancer registries through April 1, 2014 as diagnosed with an incident colorectal cancer after study enrollment. Colorectal cancer was defined by International Classification of Diseases-Oncology-3 codes C180–189, C199, and C209. We identified controls through incidence density sampling of the cohort among subjects who were free of any cancer diagnosis except skin cancer at the time of the matching case’s diagnosis. We individually matched cases and controls by age, sex, and race at a ratio of two controls for each case. Due to small sample size of white participants (68 cases), analysis was restricted to African American participants for a total of 224 colorectal cancer cases and 440 controls. The SCCS was approved by Institutional Review Boards at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Meharry Medical College. All participants provided written informed consent.

Biomarker assessment

Circulating vitamin D and vitamin D binding protein levels were measured at Heartland Assays, Inc. (Ames, Iowa). The method for quantitative determination of 25-hydroxyvitamin D was an FDA approved direct, competitive chemiluminescence immunoassay using the DiaSorin LIAISON 25-OH Vitamin D Total assay (14). This assay is co-specific for 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D2. The vitamin D binding protein measurements were completed using the polyclonal Human Vitamin D Binding Protein ELISA kit manufactured by Genway Biotech Inc. (San Diego, CA). A proxy for free circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D was calculated as the molar ratio of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to vitamin D binding protein multiplied by 105 (15).

Statistical Analysis

Frequency distributions of participant characteristics were tabulated by case-control status. Due to possible differences in sun exposure by season of blood sample draw, we created variables for 25-hydroxyvitamin D and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D that accounted for calendar week of sample collection. In separate statistical models, we regressed total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D against calendar week using the periodic function described by Gail et al. (16). Seasonal-adjusted total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin values were created by adding the residuals from the periodic function model to the mean values of total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D derived from the periodic function models. Season of participant recruitment did not vary by case status. Conditional logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between biomarker levels and colorectal cancer risk. Conditional regression statistical models included the following matched variables and potential confounders: age (5 year groupings), sex, body mass index (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, ≥35.0 kg/m2), education (<9 years, 9–11 years, high school, some college, college graduate and beyond), smoking (never, former, current), physical activity (tertiles), alcohol intake (women: none, 0< drink/day ≤1, >1 drink/day; men: none, 0< drinks/day ≤2, >2 drinks/day), history of colorectal cancer screening (yes, no/unknown), and family history of colorectal cancer diagnosis in a first degree relative (yes, no/unknown). Missing covariate data (typically for <2–4% of participants) were set to sex-specific medians. We calculated associations between vitamin D biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk with the biomarkers categorized in tertiles based on the distribution among controls and by per standard deviation change. P-values for trend tests were calculated by treating ordinal vitamin D biomarker variables as continuous in the statistical model. Additional analyses stratified by length of time between blood sample donation and case diagnosis were conducted to define a potential biologically relevant exposure period and to assess the hypothesis that colorectal cancers diagnosed soon after study recruitment might not be attributable to baseline vitamin D status. Associations between vitamin D biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk were further evaluated using conditional logistic regression statistical models among subgroups defined by sex, body mass index (BMI), and anatomic site (colon/rectum). Potential interactions between vitamin D binding protein and vitamin D levels were evaluated by completing likelihood ratio tests comparing statistical models with and without the addition of cross-product terms. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Cases and controls were similar for matched factors as well as for BMI and alcohol use (Table 1). In comparison to controls, cases tended to have less education, and lower household income. Cases were less likely to have been screened for colorectal cancer and were less likely to be current smokers. Cases and controls had similar median values for vitamin D binding protein (301.4 and 300.6 ug/ml), total 25-hydroxyvitamin D (12.5 and 13.0 ng/ml), and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D (5.8 and 6.4). African Americans had lower 25-hydroxyvitamin D biomarker values than their white counterparts; the median value for total 25-hydroxyvitamin D and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D among white controls (N=122, not included in primary analysis) were 18.6 ng/ml and 9.0. Vitamin D binding protein levels were similar for both races (300.6 ug/ml for African Americans and 299.3 ug/ml for whites). Total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D were highly correlated with each other (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.96). Vitamin D binding protein was not correlated with total 25-hydroxyvitamin D (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.01) and was negatively correlated with free 25-hydroxyvitamin D (Pearson correlation coefficient = −0.23).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of African American participants at baseline by case status, Southern Community Cohort, 2002–2009.

| Baseline Characteristic, N (%) | Controls (N=440) | Cases (N=224) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 55 (13) | 55 (13) |

| Male Sex | 203 (46.1) | 100 (44.6) |

| Education | ||

| < High school | 163 (37.1) | 104 (46.4) |

| High school | 147 (33.4) | 68 (30.4) |

| > High school | 120 (27.3) | 47 (21.0) |

| Household income, $ | ||

| < 15,000 | 275 (62.5) | 148 (66.1) |

| 15,000–49,999 | 136 (30.9) | 67 (29.9) |

| ≥ 50,000 | 16 (3.6) | 2 (0.9) |

| Colorectal cancer screening, ever | 121 (27.5) | 55 (24.6) |

| Family history of colorectal cancer | 22 (5.0) | 12 (5.4) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 28.3 (9.9) | 29.4 (10.0) |

| Current smoker | 184 (41.8) | 75 (33.5) |

| Non and moderate alcohol consumers | 337 (76.6) | 175 (78.1) |

| Physical activity, MET-hrs/day, median (IQR) | 16.3 (22.7) | 15.9 (21.0) |

| Sedentary time, hours, median (IQR) | 8.0 (6.2) | 8.0 (6.3) |

| Total energy, kcal, median (IQR) | 2212 (1748) | 2261 (1826) |

| Meat, servings/day, median (IQR) | 2 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Fruits and vegetable, servings/day, median (IQR) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Folate, micrograms/day, median (IQR) | 432 (373) | 471 (388) |

| Vitamin D supplement use | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 13.0 (10.2) | 12.5 (10.7) |

| Vitamin D binding protein, ug/ml, median (IQR) | 300.6 (56.9) | 301.4 (62.2) |

Subjects with data missing for the characteristic of interest are not included in this analysis. IQR=interquartile range.

ORs for the associations between total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D with colorectal risk indicated inverse associations, although all confidence intervals crossed unity (Table 2). A null association was observed between vitamin D binding protein and colorectal cancer risk. Results were equivalent from minimally and fully-adjusted statistical models.

Table 2.

Associations between vitamin D biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk, African American participants of the Southern Community Cohort Study.

| Biomarker | Controls | Cases | OR a (95%CI) | P-trend | OR b (95%CI) | P-trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25(OH)D, ng/ml | ||||||

| Tertile 1: ≤10.49 | 102 | 71 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Tertile 2: 10.50–16.08 | 103 | 47 | 0.65 (0.41–1.04) | 0.62 (0.38–1.01) | ||

| Tertile 3: >16.08 | 107 | 57 | 0.77 (0.48–1.21) | 0.73 (0.45–1.17) | ||

| Per standard deviation increase | 0.87 (0.71–1.06) | 0.17 | 0.82 (0.66–1.02) | 0.07 | ||

| VDBP, ug/ml | ||||||

| Tertile 1: ≤280.20 | 146 | 74 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Tertile 2: 280.21–320.00 | 145 | 69 | 0.93 (0.62–1.40) | 0.95 (0.63–1.45) | ||

| Tertile 3: >320.00 | 149 | 81 | 1.10 (0.74–1.64) | 1.08 (0.72–1.63) | ||

| Per standard deviation increase | 1.04 (0.88–1.23) | 0.66 | 1.03 (0.87–1.23) | 0.70 | ||

| Free 25(OH)D c | ||||||

| Tertile 1: ≤5.02 | 103 | 60 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Tertile 2: 5.03–7.77 | 102 | 57 | 0.92 (0.57–1.46) | 0.85 (0.53–1.39) | ||

| Tertile 3: >7.77 | 107 | 58 | 0.90 (0.56–1.44) | 0.83 (0.51–1.36) | ||

| Per standard deviation increase | 0.87 (0.71–1.06) | 0.16 | 0.82 (0.66–1.01) | 0.07 | ||

Abbreviations: OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; 25(OH)D=25-hydroxyvitamin D; VDBP=vitamin D binding protein; Ref=reference.

Analyses result from conditional logistic regression models where cases and controls are matched on age, race, and sex. Analyses are adjusted for calendar week of sample collection, and body mass index.

Additionally adjusted for education, smoking, physical activity, alcohol intake, history of colorectal cancer screening, and family history of colorectal cancer.

Free 25(OH)D biomarker is calculated as 25(OH)D:VDBP molar ratio (x103) and is a proxy for free 25-hydroxyvitamin D status.

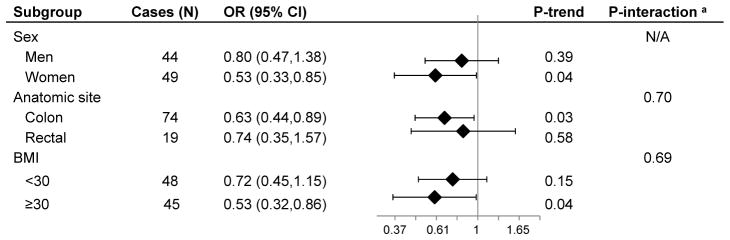

We carried out stratified analyses by the time between blood sample donation and case diagnosis to evaluate the possible influence of reverse causation and determine a biologically relevant window of exposure (Table 3, Supplementary Table). In analyses among cases diagnosed with colorectal cancer more than 3 years after blood draw and their matched controls, we found inverse associations between total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D with colorectal cancer risk. Among participants with greater than 3 years between blood draw and follow-up, a per standard deviation increase in 25-hydroxyvitamin D resulted in a 31% (95% CI: 7%–79%) decreased risk of colorectal cancer. Further analyses among these cases and their controls showed that the inverse association was more apparent in women than men, and in obese (BMI≥30 kg/m2) more than non-obese participants, although interaction tests were not statistically significant (Figure). The inverse association was somewhat stronger for colon cancer than rectal cancer (P-interaction=0.70). Analyses restricted to cases diagnosed within 3 years of blood draw and their controls produced positive but non-statistically significant associations between tertiles of total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk; among this subgroup, when total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D were modeled in per standard deviation increments, we observed null associations with colorectal cancer risk (Table 3). Results were similar, in analyses stratified by ≤ or > 2 years of time between blood draw and diagnosis (Supplementary Table). Vitamin D binding protein was not associated with colorectal cancer risk in any of the stratified analyses (Table 3). In addition, we did not observe evidence of interaction between vitamin D binding protein levels and either total or free 25-hydroxyvitamin D in risk of colorectal cancer (all P-interaction > 0.05).

Table 3.

Associations between vitamin D biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk by time since blood draw, African American participants of the Southern Community Cohort Study.

| Biomarker | Time between blood draw and cancer diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤3 years

|

>3 years

|

|||||

| Cases | OR a (95%CI) | P-trend | Cases | OR a (95%CI) | P-trend | |

| 25(OH)D, ng/ml | ||||||

| Tertile 1: ≤10.49 | 22 | 1 (Ref) | 49 | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Tertile 2: 10.50–16.08 | 28 | 1.22 (0.62–2.38) | 19 | 0.36 (0.19–0.69) | ||

| Tertile 3: >16.08 | 32 | 1.45 (0.75–2.79) | 25 | 0.45 (0.25–0.83) | ||

| Per standard deviation increase | 0.98 (0.76–1.28) | 0.90 | 0.69 (0.21–0.93) | 0.02 | ||

| VDBP, ug/ml | ||||||

| Tertile 1: ≤280.20 | 24 | 1 (Ref) | 50 | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Tertile 2: 280.21–320.00 | 25 | 1.08 (0.57–2.03) | 44 | 0.91 (0.56–1.48) | ||

| Tertile 3: >320.00 | 38 | 1.55 (0.86–2.82) | 43 | 0.85 (0.52–1.38) | ||

| Per standard deviation increase | 1.26 (1.00–1.60) | 0.05 | 0.89 (0.72–1.10) | 0.27 | ||

| Free 25(OH)D c | ||||||

| Tertile 1: ≤5.02 | 20 | 1 (Ref) | 40 | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Tertile 2: 5.03–7.77 | 29 | 1.38 (0.71–2.71) | 28 | 0.60 (0.33–1.09) | ||

| Tertile 3: >7.77 | 33 | 1.64 (0.83–3.23) | 25 | 0.51 (0.27–0.95) | ||

| Per standard deviation increase | 0.96 (0.74–1.25) | 0.76 | 0.71 (0.53–0.97) | 0.03 | ||

Abbreviations: OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; 25(OH)D=25-hydroxyvitamin D; VDBP=vitamin D binding protein; Ref=reference.

Analyses result from conditional logistic regression models where cases and controls are matched on age, race, and sex. Analyses are adjusted for calendar week of sample collection, body mass index, education, smoking, physical activity, alcohol intake, history of colorectal cancer screening, and family history of colorectal cancer.

Free vitamin D biomarker is calculated as 25(OH)D:VDBP molar ratio (x103) and is a proxy for free 25-hydroxyvitamin D status.

Figure 1. Associations between free vitamin D and colorectal cancer risk by selected participant characteristics.

Odds ratios are presented as a per standard deviation increase in level of free vitamin D and result from conditional logistic regression models where cases and controls are matched on race, age, and sex. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are adjusted for calendar week of sample collection, body mass index, education, smoking, physical activity, alcohol intake, history of colorectal cancer screening, and family history of colorectal cancer. Analyses include African American controls and cases with greater than 3 years between blood draw and diagnosis. Free vitamin D is calculated as 25(OH)D:VDBP molar ratio (x103) and is a proxy for free 25-hydroxyvitamin D status. OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval. a P-values for interaction were calculated by inclusion of cross-product terms for free vitamin D and the variable of interest. We were unable to calculate a P-value for interaction between sex and free vitamin D status because sex was used as a matching factor.

Discussion

We find inverse associations between total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk, with associations limited to cases diagnosed more than three years after their blood draw. Our study is the largest to date of the association of vitamin D and colorectal cancer risk in African Americans. Our results are consistent with potential anti-carcinogenic effects of vitamin D among African Americans and raise the possibility that lower total 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels contribute to the higher risk of colorectal cancer among African Americans than other racial groups. Other lines of evidence support an inverse association between vitamin D and overall cancer risk. Animal and cancer cell line studies show the presence of vitamin D is associated with decreased cellular inflammation and proliferation, and increased cellular differentiation and apoptosis (17–21). Additionally, the vitamin D receptor is expressed in normal colon and rectal cells (22), as is the vitamin D activating enzyme CYP27B1 (23), providing evidence that vitamin D has biologic function in these cell types.

Yet, studies in humans yield conflicting results. Secondary analyses from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) observe null associations between vitamin D supplementation and colorectal cancer risk (18,24). Additionally, a 2015 publication describing a RCT of daily vitamin D supplementation of 1000 IU for 3–5 years reports no association with risk of recurrent colorectal adenoma (25). However, these RCTs have specific limitations, most notably a small number of colorectal cancers or adenomas, limited treatment adherence, short-term follow up, and strict eligibility criteria (limited generalizability). In contrast to RCTs, observational epidemiologic evidence supports an inverse association between total circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk. A 2011 meta-analysis of prospective epidemiologic studies computed an OR for colorectal cancer of 0.66 for participants in the highest versus lowest quartile of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (2). More recent publications that described data from the Women’s Health Initiative and the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening trials also report 25-hydroxyvitamin D to be inversely association with colorectal cancer risk (9,26). Similar to these previous epidemiologic studies, we observe a decreased risk for participants in the highest versus lowest tertile of total 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and a consistent inverse association when total 25-hydroxyvitamin D is modeled in per standard deviation increments.

Several recent studies have investigated associations between colorectal cancer risk and vitamin D binding protein, free, and bioavailable 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Our results confirm the null association between colorectal cancer risk and vitamin D binding protein reported in four recent publications (8–11), and find an inverse association with free 25-hydroxyvitamin D more than three years after blood draw, which is consistent with results from one of the previous studies (9). One previous study (8), but not the others (9–11), reports inverse associations between total, free, and bioavailable 25-hydroxyvitamin D with colorectal cancer risk that were most apparent in participants with values of vitamin D binding protein below the median. We do not find evidence of interaction between vitamin D binding protein and total or free 24-hydroxyvitamin D. Anic et al (10) report positive rather than inverse associations between total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D with colorectal cancer risk using data from the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Prevention (ATBC) trial. Of note, the ATBC study only includes male smokers. Cigarette smoking may affect vitamin D metabolism; one investigation finds a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon created during cigarette smoking inactivates the hormonal form of vitamin D in cell lines, which may have implications for the association between vitamin D and colorectal cancer risk in smokers (27).

Among participants with more than three years between blood draw and diagnosis, we evaluated whether the associations between vitamin D biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk varied by sex, BMI, or anatomic site. The reduced risk ORs were primarily seen in women, and obese participants. Previous epidemiologic studies either find no difference in association by sex (28), or similar to our study, a more prominent association in women (9,29). In contrast to our study, Wu et al observed a stronger association between total 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk in participants with BMI below the median value for study participants (29). Previous studies report mixed findings for whether the association between total circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and cancer risk varies by colon or rectal site. A meta-analysis reports a stronger inverse association in rectal than colon tumors; however, the interaction is not statistically significant at P < 0.05 (2), and the largest individual study included in the meta-analysis reports stronger inverse associations with colon than with rectal tumors (28).

In the SCCS, among participants with three or fewer years between blood draw and diagnosis there are null associations between total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D with colorectal cancer risk. The presence of undiagnosed disease among cases diagnosed soon after baseline may have affected vitamin D biomarker status in these individuals. It is conceivable that participants with colorectal cancer may have changed their behavior in activities known to affect vitamin D levels, such as reduced physical activity, greater time indoors and lower sun exposure, shortly before their diagnosis. The change in activities may have led to the null association. In our study, more than three years between blood draw and diagnosis may represent a relevant biological window of exposure in the associations between circulating total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk. The natural history of colorectal cancer suggests that it make take upwards of ten years for an adenomatous polyp to develop to colorectal cancer (30). If our 25-hydroxyvitamin D biomarker categorization of high vs low status correlates with long term exposure, then it is plausible that the association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk may be most evident in participants with longer follow-up time and more time for the process of carcinogenesis to develop.

Strengths of our study include the prospective study design, and the inclusion of vitamin D binding protein, total, and free vitamin D in evaluating the association of vitamin D and colorectal cancer risk. Our study is one of the largest evaluations of vitamin D biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk in African Americans. Similar to the few previous studies that have included African American participants, we observe the inverse association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk in African Americans (9,31). Our study has limitations such that the relatively short follow-up time and limited sample size in subgroups left us without sufficient power to make definitive conclusions about the associations of vitamin D biomarkers with cancer risk in subgroups of white participants and those diagnosed with rectal cancer. Unfortunately, we did not have albumin measured for all participants consequently we were unable to assess the relationship between bioavailable vitamin D and colorectal cancer risk in this analysis, and we chose to use a proxy for free 25-hydroxyvitamin D instead of directly measuring it. However, previous studies have noted the high correlation between measured and calculated free 25-hydroxyvitamin D (32), which gives us confidence that our calculated proxy for free 25-hydroxyvitamin D is similar to actual circulating levels of the biomarker. Additionally, because this is an observational study there is the potential for residual or uncontrolled confounding factors to influence our results, and we are unable to make causal inferences about the associations between vitamin D biomarkers and colorectal cancer risk.

Conclusions

Our prospective study finds inverse associations between total and free 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk among African American participants with longer follow up. The current study adds to the limited literature on vitamin D and cancer among African Americans. Importantly, there is a high correlation between total and free circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and consequently similar associations between both measures and risk of colorectal cancer. The high correlation implies that measurement of total circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D may be the appropriate vitamin D biomarker to measure in epidemiologic studies. The relationship between vitamin D and colorectal cancer risk has been understudied in African Americans. The present investigation provides one of the few opportunities to evaluate the influence of 25-hydroxyvitamin D measures on colorectal cancer risk at lower ranges than were examined in previous studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS) is funded by grant R01 CA92447 (PI: Drs. William J Blot and Wei Zheng) from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, including special allocations from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (3R01 CA092447-08S1). Dr. Warren Andersen is supported by K99 CA207848 and the Vanderbilt Molecular and Genetic Epidemiology of Cancer training program (U.S. NIH grant R25 CA160056: awarded to Dr. Xiao-Ou Shu). Dr. Khankari is supported by the Vanderbilt Molecular and Genetic Epidemiology of Cancer training program (U.S. NIH grant R25 CA160056: awarded to Dr. Xiao-Ou Shu).

We thank Ms. Kimberly A. Kreth, and Ms. Nan Kennedy, Division of Epidemiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, for their assistance in preparing the manuscript. Data on SCCS cancer cases used in this publication were provided by the Alabama Statewide Cancer Registry; Kentucky Cancer Registry, Lexington, KY; Tennessee Department of Health, Office of Cancer Surveillance; Florida Cancer Data System; North Carolina Central Cancer Registry, North Carolina Division of Public Health; Georgia Comprehensive Cancer Registry; Louisiana Tumor Registry; Mississippi Cancer Registry; South Carolina Central Cancer Registry; Virginia Department of Health, Virginia Cancer Registry; Arkansas Department of Health, Cancer Registry, 4815 W. Markham, Little Rock, AR 72205. The Arkansas Central Cancer Registry is fully funded by a grant from the National Program of Cancer Registries, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Data on SCCS cancer cases from Mississippi were collected by the Mississippi Cancer Registry which participates in the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC or the Mississippi Cancer Registry. Cancer data for SCCS cancer cases from West Virginia have been provided by the West Virginia Cancer Registry. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the CDC or the West Virginia Cancer Registry.

References

- 1.Ma Y, Zhang P, Wang F, Yang J, Liu Z, Qin H. Association between vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3775–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JE, Li H, Chan AT, Hollis BW, Lee I-M, Stampfer MJ, et al. Circulating levels of vitamin D and colon and rectal cancer: the Physicians’ Health Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Prev Res Phila Pa. 2011;4:735–43. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, Zonderman AB, Berg AH, Nalls M, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1991–2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speeckaert M, Huang G, Delanghe JR, Taes YEC. Biological and clinical aspects of the vitamin D binding protein (Gc-globulin) and its polymorphism. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem. 2006;372:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bikle DD, Gee E, Halloran B, Kowalski MA, Ryzen E, Haddad JG. Assessment of the free fraction of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in serum and its regulation by albumin and the vitamin D-binding protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63:954–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-4-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aloia J, Mikhail M, Dhaliwal R, Shieh A, Usera G, Stolberg A, et al. Free 25(OH)D and the Vitamin D Paradox in African Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015:JC20152066. doi: 10.1210/JC.2015-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun RF, Peercy BE, Orwoll ES, Nielson CM, Adams JS, Hewison M. Vitamin D and DBP: The free hormone hypothesis revisited. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144(Part A):132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ying H-Q, Sun H-L, He B-S, Pan Y-Q, Wang F, Deng Q-W, et al. Circulating vitamin D binding protein, total, free and bioavailable 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7956. doi: 10.1038/srep07956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein SJ, Purdue MP, Smith-Warner SA, Mondul AM, Black A, Ahn J, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, vitamin D binding protein and risk of colorectal cancer in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Int J Cancer J Int Cancer. 2015;136:E654–664. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anic GM, Weinstein SJ, Mondul AM, Männistö S, Albanes D. Serum vitamin D, vitamin D binding protein, and risk of colorectal cancer. PloS One. 2014;9:e102966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song M, Konijeti GG, Yuan C, Ananthakrishnan AN, Ogino S, Fuchs CS, et al. Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, Vitamin D Binding Protein, and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer Prev Res Phila Pa. 2016;9:664–72. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Steinwandel MD, Zheng W, Cai Q, Schlundt DG, et al. Southern community cohort study: establishing a cohort to investigate health disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:972–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ. The Southern Community Cohort Study: investigating health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:26–37. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ersfeld DL, Rao DS, Body J-J, Sackrison JL, Miller AB, Parikh N, et al. Analytical and clinical validation of the 25 OH vitamin D assay for the LIAISON automated analyzer. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:867–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouillon R, Van Assche FA, Van Baelen H, Heyns W, De Moor P. Influence of the vitamin D-binding protein on the serum concentration of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Significance of the free 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 concentration. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:589–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI110072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gail MH, Wu J, Wang M, Yaun S-S, Cook NR, Eliassen AH, et al. Calibration and seasonal adjustment for matched case-control studies of vitamin D and cancer. Stat Med. 2016;35:2133–48. doi: 10.1002/sim.6856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manson JE, Mayne ST, Clinton SK. Vitamin D and prevention of cancer--ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1385–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1102022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung M, Lee J, Terasawa T, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Vitamin D with or without calcium supplementation for prevention of cancer and fractures: an updated meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:827–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Shoshan M, Amir S, Dang DT, Dang LH, Weisman Y, Mabjeesh NJ. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (Calcitriol) inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-1/vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in human cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1433–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, Giovannucci E, Feldman BJ. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:342–57. doi: 10.1038/nrc3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deeb KK, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:684–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamprecht SA, Lipkin M. Chemoprevention of colon cancer by calcium, vitamin D and folate: molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:601–14. doi: 10.1038/nrc1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobs ET, Van Pelt C, Forster RE, Zaidi W, Hibler EA, Galligan MA, et al. CYP24A1 and CYP27B1 polymorphisms modulate vitamin D metabolism in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2563–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lappe J, Watson P, Travers-Gustafson D, Recker R, Garland C, Gorham E, et al. Effect of Vitamin D and Calcium Supplementation on Cancer Incidence in Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317:1234–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baron JA, Barry EL, Mott LA, Rees JR, Sandler RS, Snover DC, et al. A Trial of Calcium and Vitamin D for the Prevention of Colorectal Adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1519–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandler PD, Buring JE, Manson JE, Giovannucci EL, Moorthy MV, Zhang S, et al. Circulating Vitamin D Levels and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Women. Cancer Prev Res Phila Pa. 2015;8:675–82. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsunawa M, Amano Y, Endo K, Uno S, Sakaki T, Yamada S, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor activator benzo[a]pyrene enhances vitamin D3 catabolism in macrophages. Toxicol Sci Off J Soc Toxicol. 2009;109:50–8. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenab M, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ferrari P, van Duijnhoven FJB, Norat T, Pischon T, et al. Association between pre-diagnostic circulating vitamin D concentration and risk of colorectal cancer in European populations:a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:b5500. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu K, Feskanich D, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Hollis BW, Giovannucci EL. A nested case control study of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and risk of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1120–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winawer SJ. Natural history of colorectal cancer. Am J Med. 1999;106:3S–6S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00338-6. discussion 50S–51S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolcott CG, Wilkens LR, Nomura AMY, Horst RL, Goodman MT, Murphy SP, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of colorectal cancer: the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2010;19:130–4. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielson CM, Jones KS, Chun RF, Jacobs JM, Wang Y, Hewison M, et al. Free 25-Hydroxyvitamin D: Impact of Vitamin D Binding Protein Assays on Racial-Genotypic Associations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:2226–34. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.