Abstract

Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia (BL) cells carry t(8;14)(q24;q32) chromosomal translocation encoding IGH/MYC, which results in the constitutive expression of the MYC oncogene. Here, it is demonstrated that untreated and cytarabine (AraC)-treated IGH/MYC-positive BL cells accumulate a high number of potentially lethal DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and display low levels of the BRCA2 tumor suppressor protein, which is a key element of homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DSB repair. BRCA2 deficiency in IGH/MYC-positive cells was associated with diminished HR activity and hypersensitivity to poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) inhibitors (olaparib, talazoparib) used alone or in combination with cytarabine in vitro. Moreover, talazoparib exerted a therapeutic effect in NGS mice bearing primary BL xenografts. In conclusion, IGH/MYC-positive Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia cells have decreased BRCA2 and are sensitive to PARP1 inhibition alone or in combination with other chemotherapies.

Keywords: Burkitt leukemia/lymphoma, MYC, BRCA2, PARP1 inhibitor, synthetic lethality

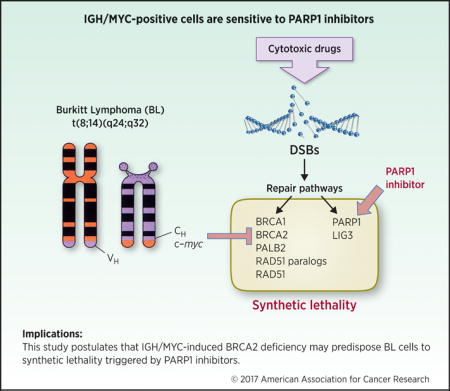

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia (BL) is a highly aggressive mature B-cell neoplasm characterized by chromosomal rearrangements of the c-myc oncogene resulting in the overexpression of MYC transcription factor (1). The most common translocation is the t(8;14)(q24;q32) (85% of all cases), which involves MYC and IGH loci to generate IGH/MYC. Deregulation of MYC, a potent proto-oncogene and transcriptional regulator contributes to lymphomagenesis through alterations in cell cycle regulation, cell differentiation, apoptosis, adhesion, and metabolism.

BL treatment consists of high-intensity chemotherapy protocols that include cyclophosphamide, cytarabine (AraC) and doxorubicin. Current therapies have achieved a very favorable outcome resulting in complete remission in 75% to 90% of BL patients and a survival rate of 70% to 80%. However, the current treatment for BL is suboptimal in elderly patients or patients with advanced-stage diseased, in the setting of HIV infections, as well as in the setting of relapsed disease. Therefore, new therapeutic strategies are necessary to improve the outcomes in BL diseases in the poor prognosis patients.

It has been reported that overexpression of MYC caused accumulation of potentially lethal DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) (2). DSBs are usually repaired by BRCA1/2 -mediated homologous recombination (HR) and DNA-PK –mediated NHEJ (D-NHEJ), whereas PARP1 -dependent NHEJ serves as a back-up (B-NHEJ) pathway (3). In addition, PARP1 may prevent accumulation of potentially lethal DSBs, either by stimulation of base excision repair and single-strand break repair and/or by promoting stalled replication fork restart (4, 5).

Here we show that IGH/MYC-positive cells display downregulation of BRCA2 tumor suppressor protein and are hypersensitive to synthetic lethality triggered by PARP1 inhibitors, either used alone, or in combination with a cytotoxic agent.

Materials and Methods

Cells

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) 1–3 from healthy donors (6), and BL-derived EBV-positive B-cell lines Mutu (generated in Dr. Paul Lieberman’s laboratory, Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and Raji (ATCC-CCL-86), and EBV-negative DG75 cell line (ATCC-CRL-2625) were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and 5 % antibiotic/antimycotic solution. All cell lines were tested for the presence or absence of EBV by western blot analysis for expression of viral antigens and DNA quantitative PCR for viral genome. Primary BL bone marrow samples were obtained from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center [karyotype: 47, XX, t1, t(8;14)(q24;q32), der(14), t(1;14)(q11;p12)]] and Perelman Stem Cell and Xenograft Core at the University of Pennsylvania [karyotype: 46,XX, t(8;14)(q24;q32)] and were cultured in StemSpan SFEM growth medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 15 % FBS, 5 % antibiotic/antimycotic solution, 20 ng/mL interleukin-3, 100 ng/mL FLT3, 50 ng/mL SCF and 10 ng/mL interleukin-7 (all from Cell Sciences, Inc.). These studies were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards and met all requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Flow cytometry

The cells were fixed and permeabilized using PerFix EXPOSE kit (Beckman Coulter) followed by staining with specific antibodies: mouse monoclonal IgG2b anti-BRCA1 (#MAB22101, R&D Systems), mouse monoclonal IgG1 anti-BRCA2 (#MAB2476, R&D Systems) and rabbit polyclonal anti-PALB2 (#A301-246, Bethyl Laboratories) conjugated with fluorochromes (Alexa Fluor-405, Alexa Fluor-488 or allophycocyanin) using Zenon labeling kit (Life Technologies). Isotype control antibodies (Abcam) were used as controls. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using LSR Fortessa (Beckton Dickinson).

Western analysis

Cells were lysed at 95°C in buffer containing 50mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol and 2% SDS and analyzed by Western blot using the antibodies detecting BRCA1 (#MAB22101, R&D Systems), BRCA2 (#MAB2476, R&D Systems), RAD51 (#sc6862, Santa Cruz Biotech.), Ku70 (#A302-623A, Bethyl Lab.), Ku80 (#MA5-15873, ThermoFisher Scientific), PARP1 (#sc7150, Santa Cruz Biotech), and RAD52 (#sc8350, Santa Cruz Biotech). Secondary goat anti-mouse and donkey anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated with IRDye 800CW IRDye 680RD were from Li-Cor Biosciences. Florescent signal from membranes was collected and analyzed using Li-Cor Bioscences equipment and software.

HR activity

HR activity was detected as described before with modifications (7). Five million cells were nucleofected with 5 μg of I-SceI –linearized HR reporter plasmid and 2.5 μg of pDsRed plasmid using Nucleofector (Lonza; program U-008, Human CD34 Cell Nucleofector® Kit). HR event restores functional GFP expression. After 72 hours the percentage of GFP+/Red+ cells in Red+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry to assess HR activity.

Nucleofection of DG75 cells

Five million cells in 100 μl nucleofection solution containing 1 μg of pmaxGFP plasmid and/or 3 μg of phCMV1_2XMBP-BRCA2 plasmid [kindly provided by Dr. Stephen Kowalczykowski (8)] were transfected using the SF Cell Line 4D-Nucleofector Kit (Lonza). GFP+ cells were sorted 72 hrs later.

In virto treatment

A triplicate of 1×104 cell line cells and 2×104 primary cells were plated in 100 μL growth medium in a 96-well plate and treated with olaparib, talazoparib and/or cytarabine (AraC) (all from Selleckchem).

γ-H2AX nuclear foci

γ-H2AX nuclear foci were detected as described before with modifications (9). Briefly, cells were treated with 2.5 μM olaparib for 24 hrs followed by cytocentrifugation, fixation, permeabilization and blocking using the ImageIT fluorescence microscopy kit (Life Technologies). Foci were detected using a rabbit monoclonal antibody specific for γ-H2AX (Millipore), and a DyLight596-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Life Technologies) with 100 nM DAPI used as a nuclear counter stain. The images were acquired with a Nikon fluorescence microscope. Post-acquisition image processing was performed using Photoshop CS6 software, with identical settings for resolution, thresholds, and scaling applied to each image within the set.

Fixable Viability Dye/γ-H2AX assay

Cells were untreated or treated with 10 nM talazoparib followed by staining with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor® 780 (eBioscience), fixation in formaldehyde and permeabilization with 100% methanol. Cells were stained with Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-H2AX (pS139) (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by flow cytometry with BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences).

Primary leukemia xenograft (PLX)

NSG female mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were injected intravenously (i.v.) with 1 × 105 BL patient cells. One week later mice were randomized in to 4 groups: control [drug vehicles], AraC [50mg/kg i.v. days 1–5) (10)], talazoparib [0.33mg/kg/day by oral gavage for 7 days (11)], and AraC + talazoparib. Human leukemia cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using anti-human CD45 antibody as described before (12). Median survival time was determined. The experiments were executed in compliance with institutional guidelines and regulations.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments and were compared using the unpaired two-tailed Student t test; p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Median survival time of the mice ± standard error was calculated by Kaplan-Meier Log-Rank Survival Analysis. Synergistic activity was determined by two-sample t test, two-way Anova, or Log-Rank test.

Results

IGH/MYC-positive cells display low levels of BRCA2 protein, reduced HR activity and sensitivity to PARP1 inhibitors

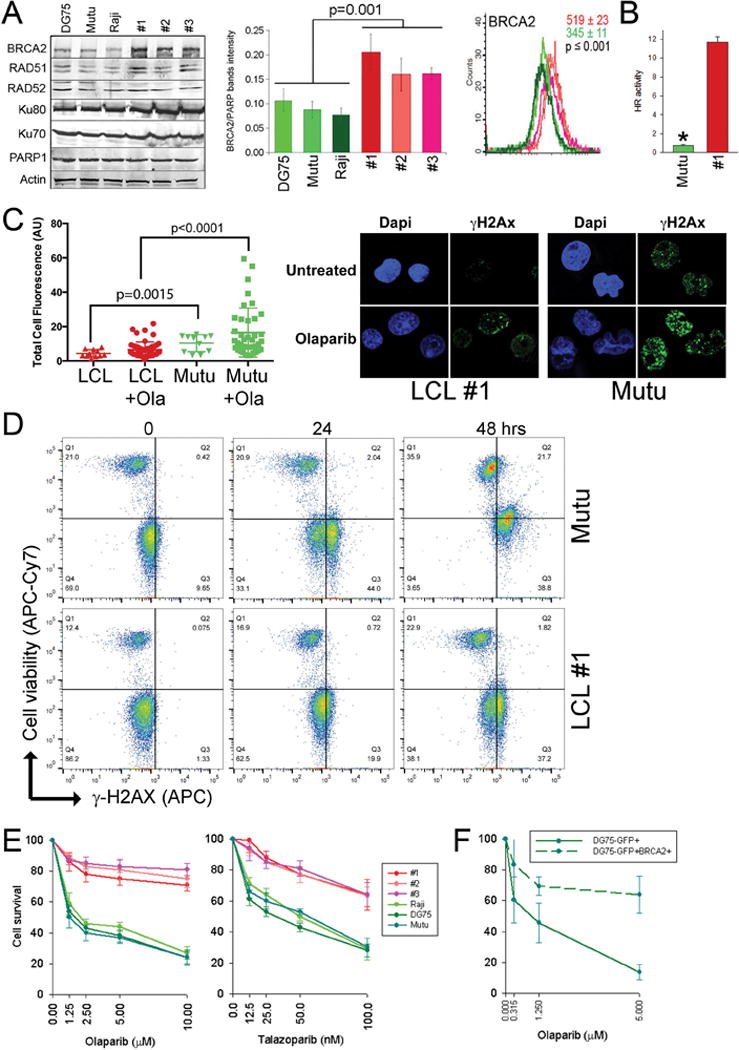

Western blot and flow cytometry detected low levels of BRCA2 protein in 3 BL-derived cell lines carrying IGH/MYC in comparison to 3 EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (Fig. 1A). Expression levels of the other key proteins in homologous recombination (BRCA1, PALB2, RAD51, RAD52) and also these in non-homologous end-joining (Ku70, Ku80, PARP1) were not altered.

Figure 1.

IGH/MYC-positive BL cell lines display downregulation of BRCA2 protein and sensitivity to PARP1 inhibitor. (A), Left panel: Representative Western blots of the expression of indicated proteins in total cell lysates obtained from BL cell lines (DG75, Mutu, and Raji) and LCLs (clones #1, #2, #3). Middle panel: Quantification of normalized BRCA2 levels to PARP1. Bars represent mean percentage volume intensity ± SD. Right panel: Immunofluorescence analysis of the expression levels of BRCA2. Overlays of representative histograms are shown. Mean values of BRCA2 immunofluorescence signal ± SD are presented in the right upper corner on each graph for 3 control (in red) and 3 lymphoma (in green) cell lines. (B) HR activity in LCL#1 and Mutu cells was measured by restoration of GFP expression from HR reporter cassette. Results represent mean ± SD from triplicates/sample; *p<0.001. (C) Left panel: cells were left untreated or treated with 2.5 μM olaparib for 48 hrs followed by detection of γ-H2AX fluorescence intensity. Right panel: Representative γ-H2AX foci are shown. (D) Cells were untreated (0) or treated with 5 μM olaparib for 24 and 48 hrs followed by staining with anti- γ-H2AX antibody and cell viability dye. Representative diagrams illustrate accumulation of γ-H2AX (right quadrangles) and dead cells (upper quadrangles). (E) A, BL cell lines DG75, Raji and Mutu, and LCL clones 1–3 were treated with the indicated concentrations of olaparib or talazoparib and cells were counted in trypan blue after 72 hrs. (F) DG75 GFP+ and DG75 BRCA2+GFP+ cells were treated with olaparib and counted in trypan blue after 72 hrs.

BRCA2 is a key factor in HR, and its downregulation impairs DSB repair (13). In concordance, low expression of BRCA2 protein in Mutu cells was associated with reduced HR activity (Fig. 1B). Impaired HR was accompanied by accumulation of higher numbers of DSBs marked by γ-H2AX nuclear foci in BRCA2-deficient IGH/MYC-positive cell lines in comparison to BRCA2-proficient LCL cells; this effect was even more pronounced after treatment with a PARP1 inhibitor olaparib (Fig. 1C). Upregulation of γ-H2AX in IGH/MYC-positive cell line was associated with increased cell death detected by the staining with a cell viability dye (Fig. 1D).

Since BRCA2 deficiency is associated with synthetic lethality triggered by PARP1 inhibitors (14), we tested the sensitivity of IGH/MYC-positive cell lines to two structurally different PARP1 inhibitors, olaparib and talazoparib. While olaparib (Lynparza) has been recently FDA approved to treat advanced ovarian cancer associated with defective BRCA genes, talazoparib is a highly potent PARP1 inhibitor in a Phase 3 study for the treatment of breast cancer with BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 mutations.

BL cell lines were much more sensitive to the PARP1 inhibitors than EBV-immortalized lymphocytes (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, the BL cell line DG75 co-transfected with GFP and BRCA2 expression plasmids (GFP+BRCA2+ cells) displayed reduced sensitivity to olaparib in comparison to the cells transfected with GFP alone (Fig. 1F).

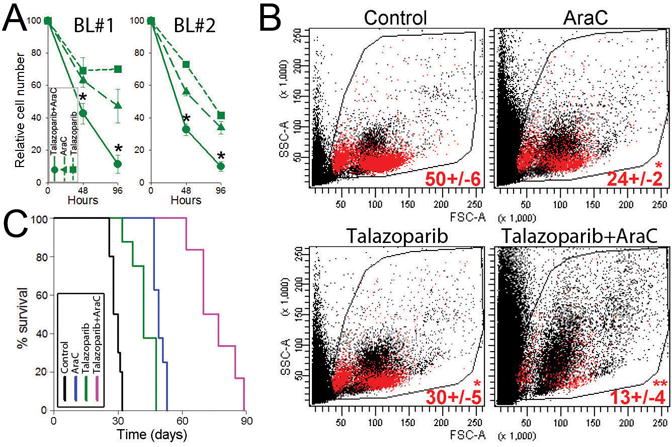

Talazoparib eliminates primary BL cells in NSG mice bearing PLXs

Primary BL cells displayed low HR activity (Supplementary Fig. S1), were sensitive to talazoparib, and a combination of talazoparib + AraC exerted synergistic activity (Fig. 2A). To test if PARP1 inhibitor exerts anti-BL activity in vivo, NSG mice injected with BL #1 patient cells developed a systemic leukemia/lymphoma-like disease. The bone marrow from the visibly sick mice displayed abundant presence of hCD45+ BL cells (Supplementary Fig. S2A). The necropsy revealed the presence of BL in multiple organs (Supplementary Fig. S2B). The spleens were enlarged and displayed diffuse replacement of the white and red pulp by the intermediate/large mononuclear cells expressing B-cell specific nuclear antigen PAX5 and germinal-center-related CD10; both highly characteristic for BL. Liver showed sinusoidal expansion by the same PAX5+/CD10+ BL cells. The bone marrow displayed massive replacement by the BL infiltrate; in kidneys the infiltrate was parenchymal with sparing of the glomeruli and tubules.

Figure 2.

Talazoparib eliminates IGH/MYC-positive primary BL cells. (A) Primary BL cells from 2 patients (BL#1 and BL#2) were treated with 10 nM talazoparib and/or 0.01 pM AraC. Results represent percentage of total living cells ± SD relative to untreated control. *p<0.01 in comparison to individual treatment using two-sample t test. (B, C) NSG mice were injected with BL#1 patient cells and 1 week later treated with diluents (Control), AraC, talazoparib, or talazoparib + AraC (6–10 mice/group). Human CD45+ (hCD45+) cells were detected in PBL 1 week after the treatment, and survival was determined. (B) Representative plots of PBL from treated mice; percentage of hCD45+ cells (red dots) is indicated. * p<0.001 in comparison to Control using Student t test; **p<0.01 in comparison to individual treatments using two-way Anova. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

NGS mice bearing BL xenografts were treated with AraC, talazoparib, and the combination of these drugs. When used individually, AraC and talazoparib reduced the number of hCD45+ BL cells in peripheral blood, but the combination of AraC + talazoparib exerted synergistic effect (Fig. 2B). Untreated mice succumbed to the leukemia/lymphoma in 29.1 ± 0.7 days (Fig. 2C) whereas these treated with AraC or talazoparib developed deadly disease after 49.5 ± 0.9 and 42.4 ± 0.2 days, respectively (p≤0.01 when compared to untreated animals). Of note, combination of AraC and talazoparib exerted synergistic therapeutic effect as the BL-bearing mice treated with the combination survived 75.5 ± 4.2 days (p<0.01 in comparison to individual drug treatments). All mice succumbed to BL-like disease as confirmed by flow cytometry detecting abundant presence of hCD45+ BL cells in peripheral blood.

Discussion

Cancer-specific defects in DNA repair pathways create the opportunity to employ synthetic lethality, already applied against cancer cells harboring deleterious mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 by using PARP1 inhibitors (14). Here we show that, in comparison to non-transformed cells, BL cells carrying IGH/MYC translocation accumulate high numbers of DSBs, display low levels of BRCA2 tumor suppressor protein accompanied by inhibition of HR activity, and are hypersensitive to PARP1 inhibitors used either alone or in combination with AraC. In addition, we detected that IGH/MYC-positive cells were also sensitive to RAD52 inhibitor (Supplementary Fig. S3), known to induce synthetic lethality in BRCA2-deficient cells (15).

Synergistic anti-BL activity of AraC combined with PARP1i is probably due to the fact that AraC cause DNA single strand breaks (16) which, if not repaired by PARP1, may lead to accumulation of lethal DSBs in BRCA2-deficient cells. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that AraC combined with olaparib resulted in selective accumulation of DSBs in BL cell line, which was associated with enhanced cell death.

The mechanism responsible for low levels of BRCA2 protein in IGH/MYC-positive cells, but it does not appear to depend on differences in proliferation rates because 26±2% of EBV-transformed cells and 31±4% of IGH/MYC-positive cells were in S-G2/M cell cycle phase. However, the presence of high levels of BRCA2 mRNA in BL cells suggests post-transcriptional regulation (Supplementary Fig. S4). High levels of c-MYC was associated with downregulation of BRCA2 protein (17) (Supplementary Fig. S5). Moreover, it has been suggested that overexpression of MYC upregulates miR-1245, which directly suppresses BRCA2 3′-UTR and translation (17). In concordance, miR-1245 was upregulated in BL cells implicating its role in downregulation of BRCA2 (Supplementary Fig. S6).

The biological relevance of low levels of BRCA2 tumor suppressor protein in IGH/MYC-positive cells remains to be determined. High copy number of MYC has been detected in prostate cancer from BRCA2 germline mutation carriers (18), suggesting that tumor cells displaying deregulated MYC may benefit from inhibition of BRCA2. This hypothesis is supported by the reports that in addition to HR, BRCA2 can also modulate transcriptional machinery by inhibiting p53-mediated transcription and/or by interaction with the transcriptional co-activator p300/CBP to regulate histone acetyltransferase activity (19, 20). Therefore, MYC-dependent transformation may collide with BRCA2-mediated activities other than DSB repair (e.g., transcriptional modulation). Thus, downregulation of BRCA2 may promote MYC-driven malignant transformation not only by inducing genomic instability but also by modulating transcriptional machinery.

In summary, low levels of BRCA2 combined with elevated levels of DSBs selectively predisposes IGH/MYC-positive lymphoma/leukemia cells to synthetic lethality triggered by DNA repair inhibitors. Therefore, patients with BL may benefit from therapy with PARP1 inhibitor, such as recently FDA approved olaparib. Moreover, PARP1 inhibitor may be useful for the treatment of other malignancies associated with deregulation of MYC, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and ALK-positive LBCL.

Supplementary Material

Implications.

This study postulates that IGH/MYC-induced BRCA2 deficiency may predispose BL cells to synthetic lethality triggered by PARP1 inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by NIH/NCI 1R01 CA186238 (T.S.).

References

- Blum KA, Lozanski G, Byrd JC. Adult Burkitt leukemia and lymphoma. Blood. 2004;104:3009–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray S, Atkuri KR, Deb-Basu D, Adler AS, Chang HY, Herzenberg LA, et al. MYC can induce DNA breaks in vivo and in vitro independent of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6598–605. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karanam K, Kafri R, Loewer A, Lahav G. Quantitative live cell imaging reveals a gradual shift between DNA repair mechanisms and a maximal use of HR in mid S phase. Mol Cell. 2012;47:320–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metzger MJ, Stoddard BL, Monnat RJ., Jr PARP-mediated repair, homologous recombination, and back-up non-homologous end joining-like repair of single-strand nicks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2013;12:529–34. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ying S, Hamdy FC, Helleday T. Mre11-dependent degradation of stalled DNA replication forks is prevented by BRCA2 and PARP1. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2814–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin KA, Cesaroni M, Denny MF, Lupey LN, Tempera I. Global Transcriptome Analysis Reveals That Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 1 Regulates Gene Expression through EZH2. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:3934–44. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00635-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slupianek A, Nowicki MO, Koptyra M, Skorski T. BCR/ABL modifies the kinetics and fidelity of DNA double-strand breaks repair in hematopoietic cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.10.005. Epub 2005 Nov 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen RB, Carreira A, Kowalczykowski SC. Purified human BRCA2 stimulates RAD51-mediated recombination. Nature. 2010;467:678–83. doi: 10.1038/nature09399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer-Morales K, Nieborowska-Skorska M, Scheibner K, Padget M, Irvine DA, Sliwinski T, et al. Personalized synthetic lethality induced by targeting RAD52 in leukemias identified by gene mutation and expression profile. Blood. 2013;122:1293–304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-501072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wunderlich M, Mizukawa B, Chou FS, Sexton C, Shrestha M, Saunthararajah Y, et al. AML cells are differentially sensitive to chemotherapy treatment in a human xenograft model. Blood. 2013;121:e90–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-464677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen Y, Rehman FL, Feng Y, Boshuizen J, Bajrami I, Elliott R, et al. BMN 673, a novel and highly potent PARP1/2 inhibitor for the treatment of human cancers with DNA repair deficiency. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5003–15. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolton-Gillespie E, Schemionek M, Klein HU, Flis S, Hoser G, Lange T, et al. Genomic instability may originate from imatinib-refractory chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. Blood. 2013;121:4175–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-466938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia F, Taghian DG, DeFrank JS, Zeng ZC, Willers H, Iliakis G, et al. Deficiency of human BRCA2 leads to impaired homologous recombination but maintains normal nonhomologous end joining. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8644–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151253498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–21. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng Z, Scott SP, Bussen W, Sharma GG, Guo G, Pandita TK, et al. Rad52 inactivation is synthetically lethal with BRCA2 deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:686–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010959107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fram RJ, Egan EM, Kufe DW. Accumulation of leukemic cell DNA strand breaks with adriamycin and cytosine arabinoside. Leuk Res. 1983;7:243–9. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(83)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song L, Dai T, Xie Y, Wang C, Lin C, Wu Z, et al. Up-regulation of miR-1245 by c-myc targets BRCA2 and impairs DNA repair. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:108–17. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castro E, Jugurnauth-Little S, Karlsson Q, Al-Shahrour F, Pineiro-Yanez E, Van de Poll F, et al. High burden of copy number alterations and c-MYC amplification in prostate cancer from BRCA2 germline mutation carriers. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2293–300. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marmorstein LY, Ouchi T, Aaronson SA. The BRCA2 gene product functionally interacts with p53 and RAD51. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13869–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuks F, Milner J, Kouzarides T. BRCA2 associates with acetyltransferase activity when bound to P/CAF. Oncogene. 1998;17:2531–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.