Abstract

The strong and ever-growing evidence base demonstrating that physical punishment places children at risk for a range of negative outcomes, coupled with global recognition of children's inherent rights to protection and dignity, has led to the emergence of programs specifically designed to prevent physical punishment by parents. This paper describes promising programs and strategies designed for each of three levels of intervention - indicated, selective, and universal – and summarizes the existing evidence base of each. Areas for further program development and evaluation are identified.

Keywords: physical punishment, spanking, discipline, intervention, prevention

Several decades of research on parents' use of physical punishment have yielded two firm conclusions. First, physical punishment generally, and spanking specifically, are ineffective at improving children's behavior and, in fact, lead to a worsening of it over time (Durrant & Ensom, 2012; Gershoff, Lansford, Sexton, Davis-Kean, & Sameroff, 2012; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; Altschul, Lee, & Gershoff, 2016). Second, physical punishment places children at risk for a range of detrimental behavioral, mental health, and cognitive outcomes, as well as for physical injury (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; Lee, Grogan-Kaylor, & Berger, 2014).

The United Nations has unequivocally stated that all physical punishment of children, no matter how ‘mild’, violates children's right to protection from violence and has called for its elimination (United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2007). To date, 51 countries have legally prohibited all physical punishment of children (Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, 2017). The United Nations' position, and the position of many family violence researchers (Durrant & Ensom, 2012; Gelles & Straus, 1988), is that the dichotomy between physical punishment and physical abuse is a false one that legitimates violence against children. Countries that maintain legal distinctions between acceptable and unacceptable physical punishment are coming under increasing international pressure to uphold children's human rights to protection and to dignity, as such distinctions condone some arbitrary level of violence against children. The UN's 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development identifies a reduction of physical punishment of children as an indicator of achievement of its goal of promoting “peace, justice and strong institutions” (United Nations, 2015, p. 1).

The strength of the evidence demonstrating physical punishment's risks and the human rights arguments against it have led increasing numbers of professional organizations serving children and families to strongly discourage physical punishment. For example, the American Academy of Pediatrics (1998 Pediatrics (2014) and the Canadian Paediatric Society (2016) have each called upon pediatricians to advise parents against physical punishment. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2012), American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children (2016), Canadian Psychological Association (2004), and National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (2011) have issued similar statements. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently published a guidance document on the prevention of child maltreatment that called for educational and legislative interventions to reduce support for and use of physical punishment as a strategy to prevent child physical abuse (Fortson, Klevens, Merrick, Gilbert, & Alexander, 2016).

Yet parents continue to physically punish their children. In a national study of families participating in the Early Head Start program in the United States, 34% of mothers reported spanking their 2- and 3-year-olds at least once in the previous week (Berlin et al., 2009). In another large community-based study of urban American families, 53% of mothers and 44% of fathers of 3-year-olds reported that they had spanked their child at least once in the past month (Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2015). Similar rates have been found in Canada. A population survey in Québec found that more than a third of parents reported spanking their children (Clément & Chamberland, 2014). Data from Canada's National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth revealed a decrease in the prevalence and frequency of physical punishment between the first (1994-1995) and final (2008-2009) survey cycles, but one-quarter of parents still reported physically punishing their children in the final cycle (Fréchette & Romano, 2015).

The fact that parents continue to use physical punishment, despite the accumulation of scientific evidence that it is both ineffective and harmful to children, indicates a clear need for strategies to prevent it. There is a particular need for interventions that translate evidence of its harms into parent-friendly messages and that support parents in changing their behavior in ways that promote their children's healthy development. To date, a variety of approaches has been used to prevent physical punishment, but there have been very few efforts to identify and synthesize these approaches. Indeed, a recent, purportedly comprehensive, review of parenting interventions by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016) neglected to include interventions aimed at reducing physical punishment. Therefore, professionals do not have a clear picture of the approaches available or of their levels of success.

The purpose of this paper is to provide examples of promising approaches and programs to shift attitudes toward physical punishment and reduce its prevalence. This article is not intended to be a systematic review of all such interventions. Rather, it is intended to describe a range of intervention strategies in order to illustrate the creative and effective methods currently being implemented.

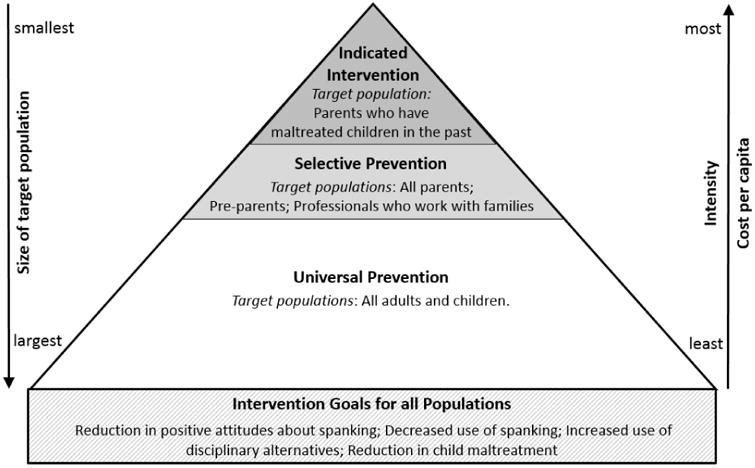

We have organized our review around the three levels of intervention identified by the Institute for Medicine (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994); namely, indicated intervention programs, selective prevention programs, and universal prevention programs. Figure 1 organizes these three intervention levels by the narrowness of their target population. Indicated intervention programs aim to reduce a negative behavior among a population that has either already displayed the behavior or is at substantial risk for doing so. Because they are targeted, these programs serve the smallest number of people and, because they tend to involve intensive services, are often the most expensive. Selective prevention programs are aimed at subgroups of the population with a collectively higher than average risk for the behavior of concern, either immediately or at some point in their lifetimes. Universal prevention programs target an entire population regardless of risk level. They are the least intensive programs but because they have the widest reach they are the least expensive per capita. In the sections that follow, we describe programs aimed at reducing physical punishment and/or the attitudes that maintain it that exemplify each level.

Figure 1.

Levels of and targets for intervention to prevent or reduce physical punishment.

Indicated Intervention Programs

Indicated interventions are targeted at subpopulations at greatest risk for a particular negative outcome. Parents who have already physically maltreated their children are thus a prime target for intensive indicated interventions aimed at preventing recurrence. Studies conducted across countries, samples, and time have consistently found that most substantiated child physical maltreatment takes place in the context of punishment. For example, the Canadian Incidence Studies of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect have consistently found that 75% of substantiated physical abuse occurs during episodes of physical punishment (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2010; Trocmé, MacLaurin, Fallon, Daciuk et al., 2001; Trocmé, Fallon, MacLaurin, Daciuk et al., 2005). ‘Mild’ physical punishment can quickly escalate to injurious levels (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; Durrant et al., 2006; Fréchette, Zoratti, & Romano, 2015), and parents under stress may be at particular risk (Taylor, Guterman, Lee & Rathouz, 2009).

Although parenting programs constitute the most common service provided to parents who become involved in the child welfare system (Casanueva, Martin, Runyan, Barth, & Bradley, 2008), relatively few explicitly counsel parents about the risks of physical punishment or advise them not to engage in it (Voisine & Baker, 2012). Below we highlight a selection of parent training interventions at the indicated level that are specifically aimed at preventing physical punishment. In Table 1, we summarize each of the programs and approaches we consider along with research evidence related to the reduction of physical punishment. The last column of the table includes ratings of the strength of the scientific evidence supporting the program that are available at the website of the California Evidence Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (CEBC; http://www.cebc4cw.org/).

Table 1.

Examples of Programs and Approaches to Prevent Physical Punishment.

| Program or Approach | Target Population | Setting | Findings Related to Physical Punishment | Level of Evidence 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicated Intervention | ||||

| Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) | Parents involved in the child welfare system (originally designed for parents of children with behavioral problems) | Multiple settings, including child welfare and clinical settings | One experimental/quasi-experimental study showed reductions in harsh parenting. | 1 |

| Incredible Years (IY) | Parents involved in the child welfare system (originally designed for parents of children with behavioral problems) | Multiple settings, including child welfare and clinical settings | Multiple experimental/quasi-experimental studies have shown that IY is effective at reducing parental physical punishment. | 1 |

| Nurturing Parenting Program (NPP) | Parents involved in the child welfare system | Multiple settings, including child welfare and community-based settings | Multiple studies of NPP have shown reductions in parents' approval of physical punishment | NR |

| Selective Prevention (Programs) | ||||

| Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) | Parents of children ≤ age 5 | Pediatric primary care | Multiple experimental/quasi-experimental studies have shown reductions in physical punishment. | 1 |

| Adults and Children Together Against Violence (ACT) | Parents | Multiple community-based settings | Multiple experimental/quasi-experimental studies have shown reductions in physical punishment. | 3 |

| Chicago Parent Program | Low-income parents | Early childhood education settings | Multiple experimental/quasi-experimental studies have shown reductions in physical punishment. | 2 |

| Early Head Start | Low-income parents | Early childhood education settings | RCT showed reduction in physical punishment. | 3 |

| Nurse-Family Partnership | Low-income mothers | Home visitation | At least one experimental/quasi-experimental studies showed reduction in physical punishment. | 1 |

| Healthy Families | Low-income mothers | Home visitation | One experimental/quasi-experimental study of Healthy Families New York showed reduction in physical punishment. | 1 |

| Cognitive Retraining (add-on to home visitation program) | Low-income mothers | Home visitation | Multiple experimental/quasi-experimental studies have shown reductions in physical punishment and ‘harsh discipline’. | -- |

| Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting | Parents | Community agencies | Non-experimental studies show reductions in parents' approval of physical punishment. | -- |

| Selective Prevention (Approaches) | ||||

| Motivational Interviewing | Parents of children ≤ age 5 | Clinical settings | One quasi-experimental study showed reductions in approval of and intentions to engage in physical punishment. | -- |

| Baby Books Project | Low-income mothers | Psychoeducation | One quasi-experimental study showed reduction in approval of physical punishment. | -- |

| Brief Online Education | Parents and college students | Online psychoeducation | Multiple experimental/quasi-experimental studies with parents and college students have shown reductions in approval of physical punishment. | -- |

| Play Nicely | Parents of children ≤ age 5 | Pediatric primary care | Multiple experimental/quasi-experimental studies have shown reductions in approval of and intention to engage in physical punishment. | -- |

| Video Interaction Project | Parents of children ≤ age 5 | Pediatric primary care | One experimental/quasi-experimental study showed reduction in physical punishment. | -- |

| Education for medical professionals | Nurses and medical residents | Medical and health care settings | Multiple experimental/quasi-experimental studies as well as non-experimental studies have shown reductions in approval of physical punishment. | -- |

| Universal Prevention | ||||

| Public education campaigns | General public | Community-based | A pre/post evaluation of an educational campaign found increased knowledge of the harms linked to physical punishment but no change in prevalence of physical punishment. | -- |

| Research summaries | Professionals | Online | Two major research reviews have been widely cited and have received hundreds of endorsements from professional and community organizations. | -- |

| Bans on physical punishment | General public | Community-based | Pre-/post-ban studies have found decreases in approval of physical punishment | -- |

We used the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (http://www.cebc4cw.org/) rating system to indicate the level of existing evidence for each program. Programs deemed to be well-supported by research evidence (“1” = the highest level of evidence) must have at least two rigorous RCTs; programs deemed to be supported by research evidence (“2”) must have at least one rigorous RCT; programs deemed to have promising research evidence (“3”) must have at least one study utilizing some form of control. CEBC gives a “Not able to be rated” (NR) designation when the program does not yet have any published experimental evaluations. Because the CEBC primarily focuses on programs with relevance to child welfare, a number of approaches in our review are not included on the CEBC website; such programs or approaches are indicated with two dashes (--).

Parent Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) is an intensive intervention involving one-on-one parent coaching to reduce negative parent-child interactions. PCIT has been adapted for parents involved with the child welfare system to include active discouragement of physical punishment, teaching of age-appropriate and nonviolent discipline strategies, and reinforcement for praising children's cooperative behavior (Chaffin et al., 2004). Participation in PCIT was associated with reduced re-referral to child protective services. The authors suggest that one mechanism by which PCIT reduced physical abuse recurrence was through a “de-escalation of coercive interactions,” including physical punishment (Chaffin et al., 2004, p. 508). This study suggests that parents who have previously harmed their children can reduce physical punishment with support.

The Incredible Years (IY) program is a group-based program aimed at reducing disruptive and aggressive behavior among children. It includes interventions at the child-, parent-, and teacher-levels (Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Beauchaine, 2011, 2013). IY was originally designed for children with behavior problems, but the parent-training component has also been used for intervention in a child welfare context (Letarte, Normandeau, & Allard, 2010; Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2012). The program uses a skill-building approach to promote positive parent-child interactions and reduce harsh parenting behaviors, such as physical punishment. IY teaches parents positive discipline approaches (e.g., praising good behavior), stress management, ways to strengthen children's prosocial and social skills, and child-directed play (Reid, Webster-Stratton, & Beauchaine, 2001). In a child welfare context, IY modules focus on helping parents understand the concepts of child-directed play, praise, and incentives in order to help parents understand the benefits of responding positively to their children (Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2012; Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2010). RCTs have shown that IY reduces physical punishment and enhances parent-child interactions, which in turn lead to reductions in behavior problems (Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Beauchaine, 2011, 2013). Declines in parents' use of physical punishment have been identified as a key mediator of IY's impact on children's disruptive and aggressive behavior (Beauchaine et al., 2005). In a study conducted among parents involved in the child welfare system, IY was associated with a significant reduction in physical punishment and in children's behavior problems (Letarte, Normandeau, & Allard, 2010).

The Nurturing Parenting Program (NPP) for Parents and their Infants, Toddlers and Preschoolers is a family-centered program designed to build nurturing parenting skills with the aim of preventing child abuse and neglect (Bavolek, 2000; Bavolek, & Hodnett, 2012). NPP has a strong focus on modifying parents' beliefs about and use of physical punishment. Cowen (2001) found that participation in NPP reduced parents' approval of physical punishment. Similarly, Thomas and Looney (2004) found declines in approval of physical punishment among at-risk adolescent parents. Another study of NPP found that participation in the program led to significant reductions in approval of physical punishment, with the most gains seen among those who had the highest initial levels of child maltreatment potential (Palusci, Crum, Bliss, & Bavolek, 2008). While a limitation of these studies is that they focus only on parental attitudes and not behavior, their findings are encouraging because parents' attitudes are a primary predictor of physical punishment (Ateah & Durrant, 2005; Clément & Chamberland, 2014; Lansford, Deater-Deckard, Bornstein, Putnick, & Bradley, 2014).

Selective Prevention Programs

Selective prevention programs target subpopulations at particular risk for physical punishment. Given the continued high prevalence of physical punishment by parents (Clément & Chamberland, 2014; Zolotor et al., 2011), the target at-risk population for selective preventions is all parents as well as professionals who may influence parents' decisions about disicpline. We have identified selective prevention programs targeting three subpopulations: 1) current parents; 2) pre-parents (individuals about to become parents for the first time); and 3) medical professionals, who have been found to have substantial influence over parents' attitudes toward physical punishment (Taylor, Moeller, Hamvas, & Rice, 2013). These programs typically involve education about the risks of physical punishment and about what parents can do instead.

Programs Targeting Parents

Positive attitudes toward physical punishment are strong predictors of its use (Clément & Chamberland, 2014; Lansford, Deater-Deckard, Bornstein, Putnick, & Bradley, 2014), as are beliefs that physical punishment is normative (Taylor, Hamvas, Rice, Newman, & DeJong, 2011). Parents with limited response repertoires also rely on physical punishment more (Combs-Orme & Cain, 2008). Therefore, reducing approval of physical punishment, altering perceptions of its normality, and exposing parents to new perspectives on discipline should reduce physical punishment's occurrence.

Screening by Primary Care Providers

Parents trust their pediatricians when it comes to childrearing advice (Taylor et al., 2013), and the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Canadian Paediatric Society have already called on physicians to discourage physical punishment (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1998, 2014; Canadian Paediatric Society, 2016). Pediatricians and primary care providers are thus logical messengers for education about physical punishment. A program specifically designed to support pediatricians in this role is Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK; Dubowitz, Feigelman, Lane & Kim, 2009), which screens families for maltreatment risk factors (Feigelman et al., 2009). Those parents who screen positive for physical punishment or other risk factors receive individualized intervention by a social worker who worked to connect the family with social services (Dubowitz, 2014). A U.S. study of at-risk urban mothers (12% had previous contact with child protective services) found that those who participated in the SEEK program reported less frequent use of harsh physical punishments, such as kicking or hitting children with a fist, by the end of the program (Dubowitz et al., 2009). A subsequent randomized RCT involving over 1,000 families who were deemed to be at low-risk (i.e., general pediatric care population) found that mothers of children under age 5 who participated in SEEK reported fewer instances of slapping or shaking, as well as less psychological aggression (Dubowitz et al., 2012).

Motivational Interviewing

Because research shows that approval of physical punishment is often embedded within cultural, religious and ideological frameworks (Taylor, Al-Hiyari, Lee, Priebe, Guerrero, & Bales, 2016), many parents may have stronger motivations to use physical punishment than to reduce it. Thus, the clinical technique of motivational interviewing may be particularly useful because it allows clients to articulate their ambivalence about change, such as conflicting beliefs about the potential benefits of physical punishment and about the pain it causes the child, while eliciting statements that convey their motivation to change their behavior (“change talk”) (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Holland and Holden (2016) created a one-session intervention using motivational interviewing to elicit “change talk” about physical punishment and tested it with a sample of mothers of 3- to 5-year-old children who reported that they used physical punishment at least once per month. Mothers randomly assigned to the intervention reported greater reductions in approval of and intentions to use physical punishment than mothers in the control group (Holland & Holden, 2016). Because it is brief, a motivational interview approach can be used by professionals who work with parents in a variety of contexts and can be incorporated into existing intervention approaches.

Home Visitation Programs

Home visitation programs present a promising platform for parent education to reduce physical punishment and other violence against children (Howard & Brooks-Gunn, 2009; Olds et al., 2014). Although a variety of home visitation models exist, they typically are designed to facilitate mother-child attachment through direct intervention during pregnancy or the first few years of the child's life. They connect at-risk mothers with professionals such as nurses (Olds, Kitzman, Knudtson, Anson, & Smith, 2014) or paraprofessionals (Olds et al., 2004) who visit their homes to provide support regarding maternal and child health and to address contextual factors such as access to services (Howard & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). Home visitation models have been found to reduce physical punishment (Howard & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). Evaluation of the Healthy Families New York home visitation program showed reductions in harsh parenting, including hitting, slapping, blaming, scolding, and threatening, among some subgroups of parents as well as increases in positive parenting skills, such as affirming, listening, reassuring, and encouraging (Rodriguez, Dumont, Mitchell-Herzfeld, Walden, & Greene, 2010). Parents in Early Start, a New Zealand-based home visitation program that counsels parents against the use of physical punishment, showed lower rates of physical assault of their children and reductions in their support of physical punishment than parents in a randomized control group (Fergusson, Grant, Horwood, & Ridder, 2005).

Attributional styles that emphasize parental perceptions of powerlessness, or beliefs that infants are “in charge” or are misbehaving on purpose, are a primary risk factor for harsh punishment of infants (Berlin, Dodge, & Reznick, 2013; Bugental, Lewis, Lin, Lyon & Kopeikin, 1999). Cognitive re-training can reduce parents' misattributions for conflict with their children while strengthening their attributions of success to their own parenting efficacy. In a series of particularly innovative studies, Bugental and colleagues (2002) tested a cognitive retraining intervention that was developed as an add-on to an existing home visitation program. Home visitors aimed to shift parents' causal appraisals for caregiving difficulties and problem solve solutions (Bugental, Ellerson, Rainey, Lin, Kokotovic, & O'Hara, 2002). For example, the home visitor would ask the mother to describe a recent parenting problem (e.g., “My baby is crying too much”). The home visitor would empathize with the difficulty of that situation, and then ask the mother why she believed the baby was crying. A mother at high risk for abuse might generate reasons that presume responsibility or intentionality of the baby, such as, “My baby has a bad personality” or “My baby is trying to make it so I can't sleep” (Berlin, Dodge, & Reznick, 2013; Bugental et al., 1999). Rather than correct the mother's misattributions, the home visitor would ask the mother if she has any other explanations for her baby's crying. In this way, the mother is given space to generate benign or non-blaming explanations for caregiving challenges, which shift attributional patterns away from blaming the baby or one's self to more developmentally appropriate explanations related to infants' caregiving needs (e.g., “Maybe my baby is tired and needs to take a nap,” or “Maybe my baby is hungry and needs to eat”). In studies involving high risk mothers, Bugental demonstrated that cognitive re-training was highly effective at reducing parental spanking, slapping, and other forms of physical child maltreatment (Bugental et al., 2002). The program was also found to reduce physical punishment among parents of medically at-risk infants, who are at particularly high risk for maltreatment (Bugental & Schwartz, 2009).

Group-Based Programs

Although one-on-one interventions have the advantage of being tailored to individual parents, they can be time- and cost-intensive. An alternative approach is to educate more than one parent at a time through group-based instruction. Groups have the added benefit of connecting parents with other parents who may be able to support or help them, both in the group itself and afterward as a social network.

One program that uses a group-based approach is the Adults and Children Together Against Violence educational program (ACT; www.apa.org/act) developed by the American Psychological Association's Violence Prevention Office (2016). Designed to be delivered in community-based and school settings, the program teaches parents about nonviolent discipline, child development, anger management, and social problem-solving skills. A specific focus of ACT is to reduce physical punishment. Several evaluations have indicated that, compared to parents in control groups, those who participate in ACT report physically punishing their children significantly less often (e.g., spanking, hitting with an object) and using positive parenting approaches significantly more often (e.g., nurturing behavior) (Knox, Burkhart, & Cromly, 2013; Knox, Burkhart, & Howe, 2011; Portwood, Lambert, Abrams, & Nelson, 2011).

Another intervention that utilizes a group-based strategy is the Chicago Parent Program (www.chicagoparentprogram.org). It was developed using a community-based participatory approach that included a parent advisory council of African American and Latino parents (Gross et al., 2009). The resulting 12-session intervention program consists of facilitated parent groups that utilize videotaped vignettes and homework assignments teaching the importance of praise and encouragement, routines, limit-setting, and problem solving. In the initial RCT evaluation with low-income African-American and Latino parents, those who participated in the Chicago Parent Program reported less frequent use of physical punishment and more frequent expressions of warmth toward their children compared to the control group (Gross et al., 2009). A second RCT evaluation, which combined the findings from the initial evaluation with a separate, larger sample, the program was again found to be effective at reducing physical punishment, as well as reducing teacher-rated externalizing and internalizing behavior problems over the subsequent year (Breitenstein et al., 2012).

A promising group-based parenting program is Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting (PDEP; www.positivedisciplineeveryday.com), which was developed through a collaboration between an academic researcher and Save the Children, a global non-profit child rights organization. The 8-week curriculum focuses on several strategies and lessons: shifting parents' attributions for the reasons underlying typical parent-child conflicts; helping them understand children's rights to protection, dignity, and participation in their learning; providing them with information on children's emotional, social and brain development from infancy to adolescence; and coaching them in implementing a framework for non-punitive problem solving (Durrant, 2013). The program has been adapted for parents with low levels of literacy, parents who are refugees or immigrants, and parents in a range of cultural, linguistic and faith communities. A pre/post evaluation found significant within-parent-group reduction in approval of physical punishment among a Canadian sample (Durrant et al., 2014). A comparison of pre- and post-test scores across 13 countries (Australia, Canada, Gambia, Georgia, Guatemala, Japan, Kosovo, Mongolia, Palestine, Paraguay, Philippines, the Solomon Islands, and Venezuela) found that, across countries, most parents believed that PDEP will have positive impacts on their parenting and their relationships with their children, and will help them to use less physical punishment (Durrant et al., 2016). To date, the focus of the program developers has been on optimizing facilitators' fidelity to the program content and delivery process across highly diverse contexts, including urban slums in Bangladesh (Khondkar, Ateah, & Milon, 2016), earthquake-affected areas of Japan (Mori, Stewart-Tufescu, & Mochizuki, 2016), and post-conflict Kosovo (Ademi Shala, Hoxha, & Ateah, 2016).

Media-Based Interventions

Some practitioners and researchers have explored using a variety of media to deliver messages about the harms associated with physical punishment and about effective disciplinary approaches. For example, the Baby Books Project incorporates information on effective parenting and child development derived from the American Academy of Pediatrics' guidelines for anticipatory guidance (Hagan et al., 2008) into baby books. The books incorporate messages discouraging physical punishment and encouraging non-punitive methods of handling children's challenging behaviors. In an RCT, first-time mothers who were randomly assigned to the educational book intervention group showed decreases in their approval of physical punishment and increases in their empathy for and appropriate expectations about their children (Reich, Penner, Duncan, & Auger, 2012). The effects were strongest among African American parents and parents with low levels of educational attainment (Reich et al., 2012).

Brief online education may also be effective at changing attitudes about physical punishment. One such intervention took the form of a slide presentation of research findings on the negative consequences of physical punishment, which parent participants read online. This “light touch” intervention found that participants' approval of physical punishment significantly decreased (Holden, Brown, Baldwin, & Caderao, 2013). Such interventions are easy to “scale up” to reach a broader audience - for example, as screensavers in office settings or on TV screens in doctors' offices - at little or no cost to practitioners and service providers.

Pediatricians' offices have also proved to be an appropriate place for a brief computer-based intervention. Play Nicely, developed by a pediatrician, is an interactive multimedia intervention that is delivered to parents via computer in primary care settings (Scholer, Hudnut-Beumler, & Dietrich, 2010). Play Nicely presents common parent-child conflict scenarios and then allows users to choose the best response from a set of options, including physical punishment (e.g., spanking), non-violent forms of punishment (e.g., time out, taking away privilege, saying no), and positive guidance (e.g., redirecting the child, praise). Parents are given feedback about which are “great options” (e.g., redirection) and which fall into a “there are better options” category (e.g., spanking). In comparison to control groups, parents who participated in Play Nicely became less likely to endorse spanking and to report an intention to spank their own children (Chavis et al., 2013; Scholer, Hamilton, Johnson, & Scott, 2010). Play Nicely is available for free online (www.playnicely.vueinnovations.com/about/play-nicely-program).

Another video-based intervention that takes place in pediatricians' offices is the Video Interaction Project, in which parents are videotaped interacting with their children (Canfield et al., 2015). A trained interventionist reviews the video with the parent to identify positive and responsive parent behaviors. Despite the fact that the intervention does not specifically focus on physical punishment, an evaluation found that parents in the video interaction group reported less frequent use of physical punishment than parents who received only pamphlets providing developmental information or those who received regular pediatric care (Canfield et al., 2015).

Early Intervention Programs

Another avenue for reaching parents is through early intervention programs promoting the development of children living in low-income families, given that some research has found physical punishment to be more common in that context (Perron et al., 2014; Ryan, Kalil, Ziol-Guest, & Padilla, 2016). In such programs, parenting education is sometimes explicit, such as through teacher home visits or parenting classes, but sometimes implicit, such as through teachers modeling positive discipline in the classroom. Early Head Start, which is a federally funded two-generation program in the United States for low-income parents of infants or toddlers, provides support for and education to parents through a combination of home visits and early childhood education for the children. An RCT evaluation of Early Head Start found that spanking frequency was significantly reduced in the treatment group compared to the control group (Love et al., 2005).

The Head Start program, which provides quality preschool for 3- and 4-year old children living in low-income families, has also been found to reduce parents' spanking over time (Puma et al., 2012) and this reduction in spanking is linked with a corresponding reduction in children's aggression over time (Gershoff, Ansari et al., 2016). This finding is particularly notable because less than half of Head Start programs offer direct parenting classes (Office of Head Start, 2015); thus, the change appears to occur whether or not parents receive direct instruction in discipline. The dataset for this evaluation did not include information on whether each center offered parenting classes (Gershoff, Ansari et al., 2016), so future research is needed to determine if there are greater reductions in physical punishment among parents at centers with parent training classes than among those at centers without such classes.

Pre-Parents

Although most physical punishment prevention programs focus on individuals who are currently parenting, it can be difficult to change behavior patterns after they have already been established. Thus, several programs have begun intervening before individuals are actually parents. These approaches tend to focus on educating individuals about the body of research linking physical punishment with harm to children and have the goal of reducing positive attitudes toward physical punishment and intentions to engage in it in the future.

One such intervention required graduate and professional students to review the published literature on physical punishment and to write a summary that included a conclusion about whether it improves children's behavior; the acts of reading and writing about the literature on physical punishment were linked with decreases in students' approval of it (Griffin, Robinson, & Carpenter, 2000; Robinson, Funk, Beth, & Bush, 2005). The online education intervention by Holden and colleagues described above was also successful in reducing approval of physical punishment among non-parent adults (Holden et al., 2013).

Adults who are just about to become parents may be especially open to information about childrearing. A one-hour education session with expectant parents that included information on risks associated with physical punishment and on positive disciplinary approaches resulted in all participants being able to successfully identify these risks (e.g., childhood aggression and physical injury) and in the majority of parents saying they planned to use the information in their own parenting (Ateah, 2013).

Medical Professionals Who Work with Families

A final target of selective prevention is professionals who work with children and families. This is an important subgroup because parents often seek the parenting advice of professionals such as physicians and psychologists (Taylor et al., 2013). Strategies aimed at this group typically have the goals of reducing professionals' approval of physical punishment and increasing the likelihood that they will actively discourage it among their patients or clients. While most pediatricians (90%) agree that they have a responsibility to screen patients for child abuse risk, only 50% believe they have had adequate training to manage high-risk cases (Trowbridge, Sege, Olson, O'Connor, Flaherty, & Spivak, 2005).

Several recent studies have evaluated approaches to educating professionals about physical punishment. Pediatric residents and third-year medical students who were exposed to the Play Nicely intervention described above became significantly more likely to report that they would counsel parents not to use physical punishment (Scholer, Brokish, Mukherjee, & Gigante, 2008). In a subsequent study, pediatric residents and medical students at a different institution were exposed to the Play Nicely program as a part of their training (Burkhart, Knox, & Hunter, 2016). The results revealed significant improvement in participants' comfort level in counseling parents regarding their children's aggressive behavior, attitudes toward spanking, and ability to generate ways of responding to children without physical punishment.

An intervention involving a one-hour presentation of research on physical punishment and other ways of responding to conflict with children was found to significantly reduce nurses' approval of spanking (Hornor et al., 2015). A medical-center-wide intervention that educated all staff about the risks associated with physical punishment and that instituted a No Hit Zone in the center resulted in significant reductions in staff support for physical punishment and significant increases in their likelihood of intervening if they observed physical punishment (Gershoff, Font et al., 2016).

These studies provide preliminary evidence that educational interventions can be an effective way of changing professionals' attitudes about physical punishment, but more research is needed, particularly with regard to whether these effects persist over the long-term and whether such interventions are successful among professionals outside the medical field.

Universal Prevention Programs

Universal prevention programs can aim to change behavior but more typically their goal is to change the attitudes that make the behavior more likely. Universal efforts to reduce positive attitudes toward physical punishment have usually taken the form of educational and media campaigns, but policy and legal interventions have become an increasingly powerful force around the world.

Universal Education

Public Education Campaigns

The most efficient way of effecting attitude change in an entire community or country is through public education campaigns. Such campaigns can involve video or audio public service announcements on radio, TV, and the internet, written content on billboards and posters, or direct mailings. As the messages in such campaigns must be brief, it can be challenging to both discourage physical punishment and encourage replacement behaviors through such approaches.

There have been no national campaigns related to physical punishment in the U.S., but several local campaigns have been implemented in Canada. Toronto's municipal government explicitly discourages parents from spanking and encourages them to use positive discipline, such as planning ahead, using praise and encouragement, and setting limits (City of Toronto, 2016). Toronto's Public Health department launched a campaign in October 2004 (Child Abuse Prevention Month) in collaboration with key agencies. It focused on the message, “Spanking Hurts More than You Think” (McKeown, 2006). More than 10,000 posters were placed at public transit stops and in community agencies and a public service announcement was televised over 4 weeks. More than 75,000 brochures in English and the main immigrant languages were distributed to service providers. The campaign materials were available on-line and were downloaded thousands of times. To evaluate the impact of the campaign on public attitudes, telephone surveys of parents were conducted before (n = 435) and after (n = 500) its implementation (McKeown, 2006). At post-test, 87%, of respondents indicated that they had found the campaign persuasive. Compared to pre-test, more parents agreed at post-test that spanking leads to aggression, long-term emotional upset, injury and parental guilt. However, there were no differences in agreement that parents have the right to spank their children (62% at pre-test, 61% at post-test) or in the proportion of parents reporting that they had physically punished their children (43% at pre-test, 47% at post-test; McKeown, 2006). This is not surprising, as once a parent has ever spanked, they would have to answer yes to that question, even if they had decided not to spank as a result of the campaign. Future evaluations of education campaigns should be sure to ask about the frequency of spanking, not just about its prevalence.

A provincial campaign is currently underway in Ontario called “Children See, Children Learn” (Best Start Resource Centre, 2016). Its aim is to educate parents about positive discipline through online videos of parents constructively managing challenges that are typical of toddlers and preschoolers (http://www.childrenseechildrenlearn.ca). The website also provides videos of parents discussing their experiences and providing positive ideas for other parents. The campaign encourages parents to sign an online pledge that they will not use “physical or emotional punishment.” This campaign was launched in early 2016 and is currently being evaluated.

Outside of North America, a range of campaigns aim to eliminate physical punishment. The most prominent of these is the Raise Your Hand Against Smacking! educational and media campaign launched in 2008 by the Council of Europe. The campaign includes video, audio, and printed materials that have been translated into 17 languages (Council of Europe, 2016a). The Council of Europe has also identified dozens of local media campaigns that aim to increase positive parenting while decreasing physical punishment, including programs in Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Ireland, Malta, Norway, and Slovakia (Council of Europe, 2016b).

Many of these campaigns have coincided with country-wide bans on physical punishment. It is difficult to know whether it is the educational campaigns or the bans that are precipitating any changes in public attitudes or parents' behavior. One study, however, has attempted to tease apart these effects. Bussman, Erthal, and Schroth (2011) examined public attitudes and parents' behavior over time in five European countries: 1) Sweden, which implemented both a physical punishment ban and an extensive public education campaign in 1979; 2) Germany, which prohibited physical punishment and implemented a national public education campaign in 2000; 3) Austria, which prohibited physical punishment in 1989 but has not implemented a very extensive public education campaign; 4) Spain, which had not prohibited physical punishment at the time of the study but had implemented nationwide campaigns on the risks of physical punishment since 1998; and 5) France, which had neither banned physical punishment nor implemented public education campaigns at the time of the study. The greatest change in attitudes and behavior was found in Sweden, where physical punishment has been prohibited the longest and where public education has been the most extensive. Of the five countries studied, Sweden had the greatest proportion of parents raising children without physical punishment – twice that found in Spain and almost five times that found in France. Other key findings from this study were: 1) physical punishment bans have both a direct impact on physical punishment frequency and an indirect effect through shifting definitions of violence and decreasing public approval of physical punishment; 2) prohibition alone has greater impact than public education campaigns alone; and 3) public information campaigns are necessary for prohibition “to fully achieve its potential effects” (p. 319).

Research Summaries

An approach taken by some professional and/or nonprofit organizations is to summarize the research on physical punishment for non-researchers, such as the general public or professionals who work with children and families but are not informed about the relevant research. An early and influential research summary is the Joint Statement on Physical Punishment of Children and Youth (Durrant, Ensom, & Coalition on Physical Punishment of Children and Youth, 2004), available on the website of the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario (www.cheo.on.ca/en/physicalpunishment). On the basis of research findings and human rights standards, this document calls for changes at the professional, policy and legal levels to end to physical punishment through universal and targeted prevention strategies. The primary functions of this document are to disseminate research findings in a concise and user-friendly way, promote awareness and discussion at organizations' executive levels, and make visible the extent of professional consensus on the issue. As of January 1, 2017, 583 Canadian organizations have endorsed the Joint Statement, including the College of Family Physicians of Canada, Canadian Association of Paediatric Health Centres, Canadian Association of Social Workers, Canadian Centre for Child Protection, Canadian Institute of Child Health, Canadian Medical Association, Canadian Nurses Association, and Canadian Public Health Association. The full list of endorsing organizations can be viewed at http://www.cheo.on.ca/uploads/advocacy/JS_Endorsers_List_En.pdf.

A few years after the Canadian Joint Statement was published, a similar report was released in the United States, the Report on Physical Punishment in the United States: What Research Tells Us About Its Effects on Children (Gershoff, 2008). It was posted on the website of Phoenix Children's Hospital (http://www.phoenixchildrens.org/community/injury-prevention-center/effective-discipline). The report called for parents to “make every effort to avoid using physical punishment and to rely instead on nonviolent disciplinary methods to promote children's appropriate behavior” (Gershoff, 2008, p. 26). Within a year of its release, 66 national and local organizations endorsed the report, including the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Medical Association, National Association of Counsel for Children, the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, and the National Parent-Teacher Association (Phoenix Children's Hospital, 2009).

Both the Canadian Joint Statement and the U.S. report were made freely available online. According to Google Scholar, the Canadian Joint Statement has been cited 63 times in published literature and the U.S. report has been cited 68 times. Both documents have been downloaded hundreds of times, suggesting wide interest in their messages.

Legal Prohibition of Physical Punishment

The most visible way for a society to express its behavioral and moral standards is through law. The ever-growing body of evidence on physical punishment's risks to children (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016), coupled with increasing global awareness of and commitment to children's fundamental human rights (Gershoff & Bitensky, 2007; Newell, 2011), has led 51 governments to date to prohibit all physical punishment of children (Global Initiative to End Corporal Punishment of Children 2017). These bans exist in all regions of the world: 29 are in Europe, 10 in Central/South America, and 7 in Africa. Fifty-five additional countries have officially committed to prohibiting all physical punishment of children.

Sweden was the first country to prohibit all physical punishment of children, in 1979. Surveys of Swedish adults conducted over several decades have revealed that approval of physical punishment dropped from just over 50% of adults in the 1960s to under 10% in 2000 (Janson, 2005). By 2011, 9 out of 10 parents believed that it was wrong to spank or slap a child, even if the parent was very angry (Janson, Jernbro, & Långberg, 2011). The proportion of parents who reported having physically punished their children dropped from 90% in the 1960s to a little over 10% in 2000 (Janson, 2005). In 2011, 14% of adolescents reported having been struck at any time during their lives; only 3% had been struck several times (Janson, Jernbro, & Långberg, 2011).

One of the goals of prohibition is to make violence against children more visible and encourage people to take action, and thus Sweden's ban was accompanied by a universal public education campaign aimed at de-legitimating violence against children. As expected, the rate of reported assaults against children increased following the ban. Analyses of reporting rates have indicated that this increase reflects increased willingness to report assaults, rather than an actual increase in assaults (Durrant & Janson, 2005; Nilsson, 2000).

Several other countries have experienced decreases in support for and incidence of physical punishment following prohibition, including Finland (Österman, Björkqvist, & Wahlbeck, 2014), Germany (Bussman, Erthal, & Schroth, 2011), and New Zealand (D'Souza, Russell, Wood, Signal, & Elder, 2016). Authors of a review of the research on physical punishment bans concluded that there was evidence to demonstrate that they have led to decreases in physical punishment and attitudes supporting it (Zolotor & Puzia, 2010).

Another approach researchers have used to assess the impact of prohibition is to compare attitudes across countries with and without bans. As noted earlier, Bussman and colleagues' (2011) cross-sectional comparison of 5,000 parents across five countries - three with bans and two without bans -found that substantially fewer parents reported physically punishing their children in the countries with bans (Austria: 18%; Germany: 17%; Sweden: 4%) than in countries without bans (France: 51%: Spain: 54%). Another cross-sectional study compared parental physical punishment and children's mental health problems by whether the country had (Bulgaria, Germany, Netherlands, Romania) or had not (Lithuania, Turkey) prohibited physical punishment (duRivage et al., 2015). The likelihood of parents reporting frequent physical punishment was 1.7 times higher in countries where it was legal. Children who were frequently physically punished had higher levels of externalizing and internalizing problems than those who experienced little to no physical punishment (duRivage et al., 2015).

It is challenging to evaluate the impact of laws and policies because countries cannot be randomly assigned to prohibit physical punishment. Therefore, the research comparing countries with and without bans must be correlational in nature. However, as increasing numbers of longitudinal studies reveal pre- to post-ban changes in parental attitudes and behavior within countries, confidence in the impact of law reform is being continually strengthened.

Study Limitations and Implications for Future Intervention

Our purpose was to provide an overview of programs that specifically aim to prevent physical punishment of children by changing adults' attitudes and/or behavior. Our aim was to represent a range of approaches that have had some measure of success. We acknowledge that not all of the interventions reviewed here have been, or could be, evaluated through RCTs – the current standard for evidence-based practice. However, many researchers are calling for a broader perspective on impact evaluation (e.g., Stern, Stame, Mayne, Forss, Davies, & Befani, 2012), as RCTs are extremely difficult to carry out in many contexts and they raise ethical concerns when parents seeking help are randomized to wait for services. Alternative methods that are gaining acceptability include qualitative comparative analysis (Befani, 2016), realist impact evaluation (Westhorp, 2014), and process tracing (Hughes & Hutchings, 2011). Exploration of these methods' application to physical punishment prevention programs would enrich the literature and generate new ideas for evaluation. In addition, a systematic review or meta-analysis of the existing literature on physical punishment intervention programs' impacts would be a useful contribution to the literature.

Another limitation of this article is the fact that virtually all of the programs we reviewed relied on parents' reports of their attitudes or behaviors for both pre- and post-intervention assessments. It is possible that parents under-report their use of physical punishment at post-test as a result of social desirability bias. We know that parents tend to under-report their use of physical punishment in general (Holden, Williamson, & Holland, 2014); this may especially be the case when parents are aware that the program in which they are participating aims to reduce their use of physical punishment. This is a difficult problem to avoid. Observation is not a feasible means of assessing reductions in physical punishment, as physical punishment is usually not a high-frequency behavior. Daily diaries may be a more valid method, as may video- or audio-recordings of families interacting in their homes (see Holden et al., 2014), although these methods are labor-intensive and expensive compared to self-report questionnaires, and all are subject to social desirability bias.

For future research on interventions to reduce physical punishment, we encourage researchers and practitioners to include plans for rigorous evaluation and replication across communities, cultures and countries. We also strongly recommend that, when feasible, children's perspectives on change in their parents' behavior be included in such evaluations. Their views and experiences have been neglected to date.

Finally, several potential avenues for preventing physical punishment have yet to be tried – or at least documented. These include providing information to members of parents' extended networks, such as their religious leaders, community leaders, and extended families, each of which can strongly influence parents' attitudes and behavior. There also is a need to target politicians' knowledge of and attitudes toward physical punishment. Interventions that take a universal, community- or country-wide approach to the prevention of physical punishment, such as legal prohibition accompanied by public education campaigns, appear necessary for widespread attitude and behavior change to occur (Bussman, Erthal, & Schroth, 2011). Therefore, we encourage researchers and practitioners to think beyond the family level when considering strategies to end physical punishment.

Conclusion

The strong evidence linking physical punishment with harm to children (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016) coupled with growing realization of children's inherent rights to protection and dignity has led to a groundswell of small- and large-scale initiatives to prevent punitive violence against children. We have identified a range of approaches that have had at least some success in reducing physical punishment and/or the attitudes that maintain its legitimacy. Community leaders and practitioners have a menu of programs from which to choose. However, gaps remain in our knowledge about how best to prevent physical punishment. Continuing evaluation of these and other approaches would be of great service to the field and to parents and children around the world.

Acknowledgments

The first author acknowledges the support for the writing of this article from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24 HD042849, PI: Mark Hayward) awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ademi Shala R, Hoxha L, Ateah C. Delivering Kosovo's first parenting program: Challenges, strategies and outcomes. International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect; Calgary, AB, August: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul I, Lee SJ, Gershoff ET. Hugs, not hits: Warmth and spanking as predictors of child social competence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2016;78:695–714. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Policy statement on corporal punishment. 2012 Jul 30; Retrieved from: www.aacap.org/aacap/policy_statements/2012/Policy_Statement_on_Corporal_Punishment.aspx.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Guidance for effective discipline. Pediatrics. 1998;101(2,Pt. 1):723–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP publications reaffirmed and retired. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1520. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children. APSAC Position Statement on Corporal Punishment of Children. 2016 Retrieved from: http://www.apsac.org/

- American Psychological Association. ACT Raising Safe Kids Program. 2016 Retrieved from: http://www.apa.org/act/

- Ateah CA. Prenatal parent education for first-time expectant parents: “Making it through labor is just the beginning…”. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2013;27:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateah C, Durrant JE. Maternal use of physical punishment in response to child misbehavior: Implications for child abuse prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:177–193. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavolek SJ, Hodnett KH. The Nurturing Parent Programs: Preventing and treating child abuse and neglect. In: Rubin A, editor. Programs and Intervention for maltreated children and families at risk. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2012. pp. 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bavolek SJ. The Nurturing Parenting Programs. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2000. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, NCJ 172848. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ. Mediators, moderators, and predictors of 1-year outcomes among children treated for early-onset conduct problems: A latent growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:371–388. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Befani B. Pathways to change: Evaluating development interventions with Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) Stockholm: Expertgruppen för biståndsanalys (the Expert Group for Developent Analysis; 2016. Retrieved from: http://eba.se/en/pathways-to-change-evaluating-development-interventions-with-qualitative-comparative-analysis-qca/ [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Reznick JS. Examining pregnant women's hostile attributions about infants as a predictor of offspring maltreatment. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:549–553. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Ispa JM, Fine MA, Malone PS, Brooks-Gunn J, Brady-Smith C, Ayoub C, Bai Y. Correlates and consequences of spanking and verbal punishment for low-income White, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development. 2009;80:1403–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best Start Resource Centre. Children See, Children Learn. 2016 Retrieved from: www.childrenseechildrenlearn.ca/

- Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Fogg L, Ridge A, Garvey C, Julion W, Tucker S. The Chicago Parent Program: Comparing 1-year outcomes for African American and Latino parents of young children. Research in Nursing & Health. 2012;35:475–489. doi: 10.1002/nur.21489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Ellerson PC, Lin EK, Rainey B, Kokotovic A, O'Hara N. A cognitive approach to child abuse prevention. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:243–258. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental D, Lewis JC, Lin E, Lyon J, Kopeikin H. In charge but not in control: The management of teaching relationships by adults with low perceived power. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(6):1367–1378. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.6.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Schwartz A. A cognitive approach to child mistreatment prevention among medically at-risk infants. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(1):284–288. doi: 10.1037/a0014031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart K, Knox M, Hunter K. Changing health care professionals' attitudes toward spanking. Clinical Pediatrics. 2016;55:1005–1011. doi: 10.1177/0009922816667313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussman K, Erthal C, Schroth A. Effects of banning corporal punishment in Europe: A five-nation comparison. In: Durrant JE, Smith AB, editors. Global pathways to abolishing physical punishment: Realizing children's rights. New York: Routledge; 2011. pp. 299–322. [Google Scholar]

- Calam R, Sanders MR, Miller C, Sadhnani V, Carmont SA. Can technology and the media help reduce dysfunctional parenting and increase engagement with preventative parenting interventions? Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:347–361. doi: 10.1177/1077559508321272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Paediatric Society. Effective discipline for children. 2016 Retrieved from: www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/discipline-for-children.

- Canadian Psychological Association. Physical punishment. 2004 Retrieved from: http://www.cpa.ca/aboutcpa/policystatements/#physical.

- Canfield CF, Weisleder A, Cates CB, Huberman HS, Dreyer BP, Legano LA, et al. Mendelsohn AL. Primary care parenting intervention and its effects on the use of physical punishment among low-income parents of toddlers. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2015;36:586–593. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanueva C, Martin SL, Runyan DK, Barth RP, Bradley RH. Parenting services for mothers involved with child protective services: Do they change maternal parenting and spanking behaviors with young children? Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30(8):861–878. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Silovsky JF, Funderburk B, Valle LA, Brestan EV, Balachova T, et al. Bonner BL. Parent–Child Interaction Therapy with physically abusive parents: Efficacy for reducing future abuse reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):500–510. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis A, Hudnut-Beumler J, Webb MW, Neely JA, Bickman L, Dietrich MS, Scholer SJ. A brief intervention affects parents' attitudes toward using less physical punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:1192–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- City of Toronto. Positive discipline: Disciplining your child without spanking or hurtingthem. 2016 Retrieved from: http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=20c60c2c0f412410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD.

- Clément ME, Chamberland C. Trends in corporal punishment and attitudes in favor of this practice: Toward a change in societal norms. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2014;33:13–17. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2014-013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coalition on Physical Punishment of Children and Youth. Canadian organizations that have endorsed the Joint Statement. 2017 Jan 1; Retrieved from: www.cheo.on.ca/en/physicalpunishment.

- Combs-Orme T, Cain DS. Predictors of mothers' use of spanking with their infants. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Strasbourg, France: 2016a. Corporal punishment. Retrieved from: www.coe.int/en/web/children/corporal-punishment. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Strasbourg, France: 2016b. Repository of good practices. Retrieved from: www.coe.int/en/web/children/repository-of-good-practices. [Google Scholar]

- Cowen PS. Effectiveness of a parent education intervention for at-risk families. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2001;6:73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2001.tb00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf I, Speetjens P, Smit F, de Wolff M, Tavecchio L. Effectiveness of the Triple P Positive Parenting Program on parenting: A meta-analysis. Family Relations. 2008;57:553–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H. The Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model: Helping promote children's health, development, and safety. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38:1725–1733. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model. Pediatrics. 2009;123:858–864. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Lane WG, Semiatin JN, Magder LS. The SEEK Model of Pediatric Primary Care: Can Child Maltreatment Be Prevented in a Low-Risk Population? Academic Pediatrics. 2012;12:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.03.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- duRivage N, Keyes K, Leray E, Pez O, Bitfoi A, Koç C, Goelitz D, et al. Fermanian C. Parental use of corporal punishment in Europe: intersection between public health and policy. PloS One. 2015;10:e0118059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza AJ, Russell M, Wood B, Signal L, Elder D. Attitudes to physical punishment of children are changing. Archives of Diseases in Childhood. 2016;101:690–693. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE. London: Save the Children; 2000. A generation without smacking: The impact of Sweden's ban on physical punishment. Retrieved from: http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/resources/online-library/generation-without-smacking-impact-sweden%E2%80%99s-ban-physical-punishment. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant J, Ensom R. Physical punishment of children: lessons from 20 years of research. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012;184:1373–1377. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101314. http://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE, Plateau DP, Ateah C, Stewart-Tufescu S, Jones A, Ly G, et al. Tapanya S. Preventing punitive violence: Preliminary data on the Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting (PDEP) program. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2014;33:109–125. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2014-018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE. Stockholm, Sweden: Save the Children Sweden; 2013. Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting (third edition) Retrieved from: http://resourcecentre.savethechildren.se/library/positive-discipline-everyday-parenting-third-edition. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE, Ensom R Coalition on Physical Punishment of Children and Youth. Ottawa: Coalition on Physical Punishment of Children and Youth; 2004. Joint Statement on Physical Punishment of Children and Youth. Retrieved from: http://www.cheo.on.ca/en/physicalpunishment. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE, Plateau DP, Ateah C, Holden G, Barker L, Stewart-Tufescu A, Jones A, Ly G, Ahmed R. Assessing the cultural relevance of a developmentally-based parenting program to reduce punitive violence in high, medium, and low human development contexts. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2016 Manuscript accepted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant J, Trocmé N, Fallon B, Milne C, Black T, Knoke D. Punitive violence against children in Canada. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto, Faculty of Social Work; 2006. CECW Information Sheet #41E. Retrieved from: http://cwrp.ca/publications/497. [Google Scholar]

- Feigelman S, Dubowitz H, Lane W, Prescott L, Meyer W, Tracy JK, Kim J. Screening for harsh punishment in a pediatric primary care clinic. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.011. doi:0.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Grant H, Horwood J, Ridder EM. Randomized Trial of the Early Start Program of Home Visitation. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):e803–e809. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortson BL, Klevens J, Merrick MT, Gilbert LK, Alexander SP. Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childmaltreatment/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Fréchette S, Romano E. Change in corporal punishment over time in a representative sample of Canadian parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2015;29:507–517. doi: 10.1037/fam0000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fréchette S, Zoratti M, Romano E. What is the link between corporal punishment and child physical abuse? Journal of Family Violence. 2015;30:135–148. doi: 10.1007/s10896-01409663-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ, Straus MA. Intimate violence. New York: Touchstone; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Columbus, OH, and Phoenix, AZ: Center for EffectiveDiscipline and Phoenix Children's Hospital; 2008. Report on Physical Punishment in the United States: What Research TellsUs About Its Effects on Children. Retrieved from: http://www.phoenixchildrens.org/community/injury-prevention-center/effective-discipline. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Spanking and child development: We know enough now to stop hitting our children. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:133–137. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Bitensky SH. The case against corporal punishment of children: Converging evidence from social science research and international human rights law and implications for U.S. public policy. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2007;13:231–272. doi: 10.1037/1076-8971.13.4.231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Corporal punishment by parents and its consequences for children: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology. 2016;30:453–469. doi: 10.1037/fam0000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Ansari A, Purtell KM, Sexton HR. Journal of Family Psychology. Advance online publication; 2016. Changes in parents' spanking and reading as mechanisms for Head Start impacts on children. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/fam0000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Font SA, Taylor CA, Foster RH, Garza AB, Olson-Dorff D, Terreros A, Nielsen-Parker M, Spector L. Effectiveness of a No Hit Zone policy in reducing staff support for and intervention in physical punishment in a hospital setting. Manuscript in preparation 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Lansford JE, Sexton HR, Davis-Kean P, Sameroff AJ. Longitudinal links between spanking and children's externalizing behaviors in a national sample of White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American families. Child Development. 2012;83:838–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. States which have prohibited all corporal punishment. 2017 Retrieved from: http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/progress/prohibiting-states/

- Griffin MM, Robinson DH, Carpenter HM. Changing teacher education students' attitudes toward using corporal punishment in the classroom. Research in the Schools. 2000;7:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Garvey C, Julion W, Fogg L, Tucker S, Mokros H. Efficacy of the Chicago Parent Program with low-income African American and Latino parents of young children. Prevention Science. 2009;10:54–65. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. 3rd. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. Bright Futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. Retrieved from: https://brightfutures.aap.org/materials-and-tools/tool-and-resource-kit/Pages/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Hoath FE, Sanders MR. A feasibility study of Enhanced Group Triple P — Positive Parenting Program for parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behaviour Change. 2002;19:191–206. doi: 10.1375/bech.19.4.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Brown AS, Baldwin AS, Caderao KC. Research findings can change attitudes about corporal punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;38:902–908. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Williamson PA, Holland GWO. Eavesdropping on the family: A pilot investigation of corporal punishment in the home. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28:401–406. doi: 10.1037/a0036370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0036370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland GWO, Holden GW. Changing orientations to corporal punishment: A randomized control trial of the efficacy of a motivational approach to psycho-education. Psychology of Violence. 2016;6:233–242. doi: 10.1037/a0039606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hornor G, Bretl D, Chapman E, Chiocca E, Donnell C, Doughty K, et al. Quinones SG. Corporal punishment: Evaluation of an intervention by PNPs. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2015;29:526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard KS, Brooks-Gunn J. The role of home-visiting programs in preventing child abuse and neglect. The Future of Children. 2009;19(2):119–146. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Hutchings C. New Delhi: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation; 2011. Can we obtain the required rigour without fandomisatioin? Ofam GB's non-experimental Global Performance Framework. Retrieved from: http://www.ipdet.org/files/Publication-Can_we_obtain_the_required_rigour_without_randomization.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Janson S. Response to Beckett, C. (2005) ‘The Swedish myth: The corporal punishment ban and child death statistics’. British Journal of Social Work. 2005;35(1):125–38. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bch369. British Journal of Social Work, 35 1411-1415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janson S, Jernbro C, Långberg B. Kroppslig bestraffning och annan kränkning av barn I Sverige: En nationell kartläggning (Corporal punishment and other abuse of children in Sweden: A national survey) Stockholm: Stiftelsen Allmänna Barnhuset (Children's House Foundation); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Khondkar L, Ateah C, Milon FI. Implementing ‘Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting’ among ethnic minorities, urban slums, and brothel areas of Bangladesh. International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect; Calgary, AB, August: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Knox M, Burkhart K, Cromly A. Supporting positive parenting in community health centers: The ACT Raising Safe Kids Program. Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;41:395–407. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knox M, Burkhart K, Howe T. Effects of the ACT Raising Safe Kids parenting program on children's externalizing problems. Family Relations. 2011;60:491–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00662.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Bradley RH. Attitudes justifying domestic violence predict endorsement of corporal punishment andphysical and psychological aggression towards children: A study in 25 low-and middle-income countries. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;164:1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]