Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM), the most aggressive brain tumor in human patients, is decidedly heterogeneous and highly vascularized. Glioma stem/initiating cells (GSC) are found to play a crucial role by increasing cancer aggressiveness and promoting resistance to therapy. Recently, crosstalk between GSC and vascular endothelial cells has been shown to significantly promote GSC self-renewal and tumor progression. Further, GSC also transdifferentiate into bona-fide vascular endothelial cells (GEC), which inherit mutations present in GSC and are resistant to traditional anti-angiogenic therapies. Here we use 3D mathematical modeling to investigate GBM progression and response to therapy. The model predicted that GSC drive invasive fingering and that GEC spontaneously form a network within the hypoxic core, consistent with published experimental findings. Standard-of-care treatments using DNA-targeted therapy (radiation/chemo) together with anti-angiogenic therapies, reduced GBM tumor size but increased invasiveness. Anti-GEC treatments blocked the GEC support of GSC and reduced tumor size but led to increased invasiveness. Anti-GSC therapies that promote differentiation or disturb the stem cell niche effectively reduced tumor invasiveness and size, but were ultimately limited in reducing tumor size because GEC maintain GSC. Our study suggests that a combinatorial regimen targeting the vasculature, GSC, and GEC, using drugs already approved by the FDA, can reduce both tumor size and invasiveness and could lead to tumor eradication.

Keywords: Cancer Stem Cells, Feedback Control, Anti-cancer Therapies, Glioblastoma, Mathematical Model

Major Findings

We developed a 3D mathematical model to investigate GBM growth and its response to cancer therapies. We demonstrated that GBM stem cells (GSC) can drive invasive fingering and that transdifferentiated vascular endothelial cells with GSC origin (GEC) spontaneously form a network within the hypoxic core. In addition, current standard-of-care therapies decrease tumor size but increase invasiveness. Anti-GSC therapies may decrease tumor invasiveness and size but may be ultimately limited in reducing tumor size because GEC provide support for GSC proliferation and self-renewal. We suggest that a combination of anti-angiogenic, anti-mitotic, differentiation and anti-GEC therapy using FDA-approved drugs will greatly reduce both tumor growth and invasion, and could eradicate the tumor without recurrence when the treatment is stopped.

Quick Guide to Equations and Assumptions

Continuum tumor growth model

We follow (1) and model tumor cell species as volume fractions. In particular, we model GBM stem cells (GSC, φGSC), committed progenitor GBM cells (GCP, φGCP ), terminally differentiated GBM cells (GTD, φGTD ), vascular endothelial cells generated by transdifferentiation of GSC (GEC, φGEC ) and dead GBM cells (DC, φD ). The volume fraction of total tumor cells is φT = φGSC + φGCP + φGTD + φGEC + φD. We assume that the solid region (φS ) consists of tumor cells and the host tissue (φH ), and that the fractions of the solid region and interstitial water (φW ) are constant and add up to 1. Namely, we take φS = φT + φH and φS + φW = 1. The volume fractions of tumor cells are normalized by φS.

The fractions of tumor cell species, the host tissue and the solid region satisfy the mass conservation equation

| (1) |

where i = GSC, GCP, GTD, GEC, DC, T, H or S. Ji are fluxes that account for mechanical interactions among tumor cells. The mass is conserved only if ΣiJi is constant and ΣiSrci = 0 (1). We take Ji = Mφi∇μ, where M is the cell mobility. To model the chemical potential μ, we introduce adhesion energy , where γ measures cell to cell adhesion, is a double-well potential that penalizes mixing of the tumor (φT ≈ 1 ) and host tissues (φT ≈ 0). We take μ as the variational derivative of the adhesion energy, namely .

The term ∇ · (usφi) models passive cell movement (advection), where us is the mass-averaged velocity of solid components defined by Darcy’s-like law

where p is the solid, or mechanical pressure. To solve for p, we sum up Eq. (1) for all tumor cell components and the host tissue, and define SrcT = SrcGSC + SrcGCP + SrcGTD + SrcGEC + SrcD as the mass exchange term for total tumor cells. Note that JS = JT + JH is constant, it follows that ∇ · us = SrcT + SrcH. We assume that the mass exchange in host tissue is zero (SrcH = 0), e.g. homeostasis. Therefore, ∇ · us = SrcT and the solid pressure can then be solved by

It can be shown that the adhesion energy is non-increasing in time in the absence of cell proliferation and death, given our choices of flux and velocity terms (1). To model the advection of cell substrates with the interstitial liquid velocity uw, we also use Darcy’s-like law to relate the water pressure q and uw by uw = −∇q. Following (1), we assume that Jw = 0, i.e. no adhesive flux of water. Since φS + φW = 1 and ΣiSrci = 0, we obtain ∇ · uW = −SrcT, therefore −∇2q = −SrcT.

Mass Exchange Term

The source terms Srci in Eq. (1) account for tumor cell proliferation, self-renewal and differentiation. In particular, GSC proliferate at base rate . GSC may self-renew with possibility p0, differentiate to GCP, or transdifferentiate to GEC with branching probability r. GCP may self-renew with probability p1 or differentiate to GTD. GTD undergo apoptosis at rate , and DC are subject to lysis at rate . The mass exchange terms are

We note that Eq. (1) is only solved for φT, φGSC, φGCP, φGEC and φD. The volume fraction of GTD is calculated by φGTD = φT − φGSC − φGCP − φGEC − φD.

We assume that GSC produce a short-range activator W (e.g. Wnt (2)), with concentration CW, that promotes the probability of GSC self-renewal p0, and a longer-range W-inhibitor (WI, e.g. Dkk (3)), with concentration CWI, that constitute a Turing-type pattern formation system (4). GTD secrete factors T1 and T2 (e.g. TGF-β superfamily members (5)), with concentrations CT1 and CT2, that reduce GSC and GCP self-renewal probabilities, respectively. In addition, to model the maintenance of GSC by vascular endothelial cells lining the capillaries in the tumor microenvironment, the endothelial cells are assumed to secrete a soluble signaling factor F, with concentration CF, that increases p0 and the GSC division rate. We take

where the maximum and minimum self-renewal levels are and and are the positive feedback gains due to W and F respectively, and ψ0 is the negative gain due to T1. Analogously, we take the GCP self-renewal probability to be

where and are the maximum and minimal self-renewal rate of GCP, is the positive feedback gains due to W, and ψ1 is the negative gain due to T2.

We take the GSC mitosis rate to be

where is the base proliferation rate, is the positive feedback gain by CF and is the maximum fold change.

Cell Substrates

Because nutrient diffusion occurs more rapidly than cell proliferation, the nutrient concentration (n) satisfies the quasi steady state equation (1)

where Dn is the nutrient diffusivity, and are the uptakes rates by GSC, GCP and GTD respectively. dn is the natural decay of nutrients. Q(φT) ≈ 1 − φT approximates the characteristic function of the host tissue. and are the nutrient supply rates from the pre-existing and functional neo-vessels (ρFV) respectively. n̄ = 1.0 is the nutrient concentration in the microenvironment.

We take a generalized Gierer-Meinhardt model for the short-range self-renewal promoter CW and longer-range inhibitor CWI:

where ∇ · (uwCW) and ∇ · (uwCWI) model advection with the interstitial water velocity, DW and DWI are the diffusivities. Note that the full time dependent equations are used here because we assume that W and WI are less diffusive than the nutrient and change over slower time scales (4). We note that similar results could be obtained if the equation for WI, but not W, was taken to be quasi-steady (results not shown). We take the source terms

where k is the reaction rate, pW, pWI are production rates, dW and dWI are natural decay rates. u0 models a background nutrient-dependent production of CW from all viable cells.

In addition, we assume that GTDs produce negative feedback regulators CT1 on GSC self-renewal and CT2 on GCP self-renewal. Assuming that these factors are also rapidly diffusing, we take (4)

where DT1, dT1 and pT1 are the diffusivity, natural decay and production rates by GTDs, respectively. is the uptake rate by GSCs; parameters for CT2 are defined analogously.

Following the angiogenesis model in (1), we assume that the vascular network is stimulated by soluble angiogenic regulators (e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF [1]), which we model using a single variable CV representing the total concentration of pro-angiogenic factors (henceforth referred to as VEGF). In particular,

where DV, dV and pV are the diffusivity, natural decay and production rates of VEGF respectively. We assume that VEGF is produced by viable cells (whose volume fraction is φGSC + φGCP + φGTD = φT − φD ) in regions of hypoxia. H(x) is the Heaviside function (H(x) = 1 when x > 0; H(x) = 0 otherwise), and ñ is the hypoxia threshold so that viable cells produce VEGF when the nutrient level n < ñ.

The concentration CF of the vascular-produced GSC promotor satisfies a reaction-diffusion-advection equation that accounts for its production from the angiogenic vasculature and transdifferentiated GEC:

where DF and dF are the diffusivity and the natural decay rate, and are the production rates by the vasculature and GEC respectively. ρV is the vessel density function, F̄ is concentration of CF in the vasculature.

The nondimensionalization of the model, and the parameters for the tumor in Fig. 2 are listed in Sec. S1 in Supplemental Materials. Although we present results for this basic set of parameters, the behavior we present is characteristic of that obtained by a wide range of parameter choices.

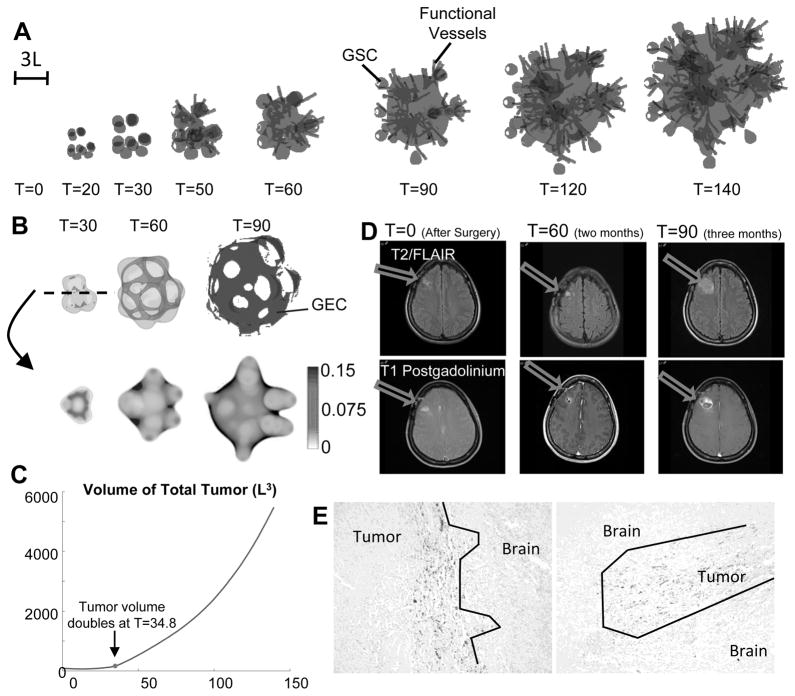

Fig. 2.

Evolution of untreated vascular tumor. (A) Spatial distribution of tumor cells (gray: tumor boundary; black: φGSC=0.3) and functional vessels (gray lines). Color version in SM. (B) Transdifferentiated GEC spontaneously form a network structure. Top: 3D isosurfaces of tumor boundary and φGEC=0.1 (dark gray) at T=30 and T=60. Bottom: 2D slices of φGEC at the center of computational domain. (C) Time evolution of total tumor volume. L is the diffusional length scale (≈ 250θM). At T=34.8, tumor volume doubles from T=0 (after surgery). (D) Exponential growth and central cavitation in a patient that declined treatment. Without treatment, tumor volume can double in 2–4 weeks. Two months after surgery, residual enhancement is gradually enlarging and more than doubled in size three months after surgery. (E) GBM infiltrates the normal brain. GSCs are positioned at the edge of the invading zone. Patient tumors, IHC staining with GSC marker, TRIM 11 (50).

We model tumor angiogenesis following (1), which generates a vascular network independent of the computational grid (lattice-free) and stimulated by soluble angiogenic regulators (e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF (6)). We assume that viable tumor cells in the hypoxic core (when the nutrient level is below a threshold) produce VEGF. Similar results are obtained where GSCs produce twice as much VEGF as non-GSCs (7). Vessel sprout sites are selected at a constant probability once the VEGF concentration is higher than a threshold. The vessel tip cells move using a circular random walk model. At each time step, the tip cell has a fixed probability to divide into two tip cells to create a branch in the vessel. Once a tip cell is close to another vessel, the two vessels may connect, with a constant probability, and form loops (anastomose). At this point the vessels begin to deliver cell substrates to the microenvironment, e.g. nutrients to the tumor. The contribution from all vessel segments that supply cell substrates is integrated to obtain the effective vascular density. We refer to (1) for further details. Since tumor cells increase the solid pressure when they proliferate, vessels are crushed and removed from the simulation with a certain probability when the pressure is sufficiently high. The model is illustrated in Fig. 1A.

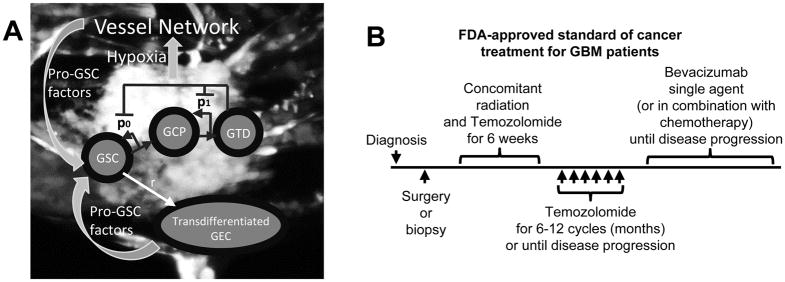

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the cancer model and the standard-of-care treatment regimen for GBM patients. (A) Image of vascularized GBM and model schematic. GBM cells (U-87, GFP-transduced), along with endothelial cells (EC, m-Cherry transduced) and fibroblasts were grown in a microfluidic device. Color version in SM. After 4 to 6 days, the endothelial cells develop a fully formed vascular network, which is perfused by cell media. (B) FDA-approved standard of cancer treatment for GBM patients. After surgery or biopsy is performed following diagnosis, six weeks of concomitant radiation and temozolomide are applied. Then, temozolomide is applied for 6–12 cycles (months) or until disease progression (McDonald criteria, i.e. tumor grows more than 25% of surface area). Afterwards, bevacizumab is applied as single agent or in combination with chemotherapy until disease progression.

Introduction

Glioblastoma (World Health Organization Grade IV Astrocytoma, GBM) is the most aggressive brain tumor. More than ten thousand GBM patients die each year in the United States. The median patient survival for GBM is less than 12 months, according to the most recently published statistical data (CBTRUS Statistical Report 2012) (8). It remains a challenge to eradicate glioblastoma due to its high heterogeneity, intense vascularization and innate treatment resistance.

The cancer stem cell hypothesis (i.e. a group of cells are capable of initiating a new tumor mass and differentiate into other tumor cell hierarchies) in glioblastoma has been extensively studied (9). The glioma stem cell (GSC) hierarchy is found to play a crucial role in tumor development and therapy resistance. Tumors with higher stem cell populations are more aggressive and vascularized than those with fewer or no stem cells (6). GSCs are also able to initiate tumors when implanted in animal models at a much higher rate than non-GSC glioma cells.

GSCs (Nestin+) are frequently located close to the capillaries, and GSCs cultured with endothelial cells (ECs) maintain their proliferation and self-renewal properties (10), even when GSCs do not directly contact with ECs. This suggests an EC-GSC crosstalk in glioma with ECs providing support for GSCs. Possible signaling mechanisms include perivascular nitric oxide (11) and Interleukin-8 signaling (12). In addition, recent studies in (13,14) have found that cells facing the lumen in glioma blood vessels were carrying both specific endothelial markers (CD31) and mutations – such as EGFR variant vIII (EGFR vIII) – that are identical to mutations found in GBM (15). Further, in xenografts of human GBM in immune compromised mice, ECs with human CD31 were found in the tumor center even though such cells were not implanted (13). When culturing GSCs in EC conditions, the cells showed an EC phenotype and expressed endothelial markers. However, this was not observed on non-stem cell lines (13,14). Taken together, these results suggest that GSCs are capable of transdifferentiating into bona fide ECs and thus GSCs actively participate neovasculature formation. These transdifferentiated cells have been found in the core of the tumors and in particular close to the hypoxic regions (13). Moreover, in (16) the authors found that transdifferentiated cells may have pericyte characteristics. Thus, many questions regarding these GSC-derived cells remain.

Over the last few decades, various therapies have been studied and tested clinically. The standard of care treatment for newly-diagnosed GBM patients consists of surgical resection of the tumor, followed by combined radiation and chemotherapy (temozolomide) and single-agent chemotherapy (17), see Fig. 1B. Unfortunately, almost all the patients progress during or shortly after the temozolomide treatment. Anti-angiogenic therapy (e.g. bevacizumab) has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma patients. Bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody which neutralizes vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secreted by tumor cells to promote the formation of new tumor blood vessels that supply nutrients and oxygen (6). In bevacizumab-treated patients, the number of tumor blood vessels decreases, but two different studies showed no significant improvements in patient survival rate when bevacizumab is initiated in newly-diagnosed patients (18). Additionally, increased tumor invasiveness following anti-angiogenic therapy has been reported (19).

Tumor recurrence is frequently observed following the standard of care treatments. This prompts the development of new, personalized and more effective therapies. Along these lines several therapies targeting GSCs have been developed to minimize recurrence (GSCs are tumor-initiating), reduce aggressiveness and reduce resistance to therapies (GSCs are less sensitive to cytotoxic drugs and radiation). One of the most frequently used differentiation therapies is the drug-induced differentiation of GSCs by all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA, derivate of vitamin A (20)), and by 13-cis-retinoic acid – both of which can achieve high levels in the brain and have been shown to successfully differentiate both neural stem/precursor cells (NSCs) and GSCs. These retinoic acids were extensively used in malignant glioma treatment in the pre-bevacizumab era (21). The blockage of several other signaling pathways using clinically-ready drugs has been shown to affect GSC self-renewal, proliferation and differentiation (e.g. Notch, Wnt and Shh signaling pathways (22)), and are currently under study in patients.

Furthermore, the amplification of different cell receptor tyrosine kinases (such as EGFR and the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)) is related to glioma progression. EGFR is amplified in approximately half GBM tumors (23) and mutated to a constitutively active form – EGRF vIII in 20% to 40% of the GBMs (24)). The same mutation has also been found in transdifferentiated ECs as mentioned above (14,15). The presence of EGFR vIII is correlated with worse prognosis (23) and its expression is frequently associated with CD133 positive GSCs (15). Multiple clinical trials of EGFR inhibitors (erlotinib, lapatinib, etc.) were conducted in GBM patients but none improved patient outcome perhaps due to a low ability to cross the blood brain barrier and achieve relevant doses., However, successful treatments of brain metastases from other malignancies using EGFR inhibitors (lapatinib, afatinib) suggest that the lack of efficacy in GBM might instead be related to the heterogeneity of GBM and drug resistance (25). Since these therapies are FDA approved and potentially easy to translate in a clinical trial setting, we perform a mathematical study to help understand how these therapies affect glioma growth and to identify effective combination therapies for further study in clinical trials.

Mathematical models of GBM range from discrete agent-based models, which track the behaviors of individual cells, to cellular automaton models, which describe the motion of discrete cells on a lattice and enable simulations at super-cell scales, to continuum models that track the dynamics of cell densities or volume fractions at tissue-level scales. See recent review articles for further details and references (26–28). Because of their simplicity, continuum reaction-diffusion equations have been widely used to describe the infiltration of GBM cells in the brain (29–31) and to develop patient-specific therapeutic approaches (32,33). Here, we use a continuum-level multiscale, mixture type model, extending previous work (4,7) to simulate the dynamics of GBM stem, GBM progenitor, transdifferentiated endothelial cells, terminally differentiated, dead cells. The GBM system is coupled to a discrete angiogenesis model from (1), extended to account for cross-talk between GBM cells and the vascular network.

Materials and Methods

We model GBM tumor progression in 3D by solving numerically a multispecies mixture model adapted from (1,4,7). The equations are solved in dimensionless form using the diffusional length of nutrients as the length scale (L), e.g. around 250 microns, and the cell cycle of a GCP, e.g. around 24 hours, as the time scale (T). Tumor cell species are modeled as volume fractions that satisfy mass conservation equations that account for cell motility, mitosis, apoptosis and changes in cell fate. Cell proliferation increases the local solid pressure, and tumor cells move from high pressure to low pressure regions. Spatiotemporally varying signaling factors secreted by tumor cells and vascular endothelial cells regulate cell proliferation, differentiation and cell fates. In particular, GBM stem cells (GSC) may transdifferentiate into vascular endothelial cells (GEC) or differentiate to GBM committed progenitor cells (GCP). GCPs may self-renew or differentiate into GBM terminally differentiated cells (GTD). GSCs release a short-range factor that promotes GSC self-renewal, and a long-range inhibitor of this factor. GTDs release signaling factors that inhibit the self-renewal of GSC and GCPs. Vascular endothelial cells secrete a factor that increases GSC self-renewal. See Sec. S2 in SM for details.

We also account for a vascular network stimulated by soluble angiogenic regulators (e.g. VEGF) released by hypoxic tumor cells using the method described in (1). Vessel sprout sites are selected randomly from an underlying vasculature (assumed to be uniformly distributed) where the VEGF level is sufficiently high. The vessel tip cells move in a circular random walk, and may form loops (anastomose) when two tip cells are close. Looped vessels deliver cell substrates (e.g. nutrients) to the microenvironment. Vessels may also be shut down by solid pressure created by tumor cell proliferation. See (1) for details. The model is illustrated in Fig. 1A.

Results

We simulate the dynamics of a GBM tumor in 3D using our computational model (Fig. 1A; Methods; SM). The tumor starts as a perturbed avascular spheroid that consists of a uniformly distributed mixture of cells: 10% glioma stem (GSC), 25% committed progenitor (GCP), 60% terminally differentiated (GTD) and 5% dead cells (DC; necrotic areas are a hallmark of GBM). We assume that initially there are no GECs. We use this configuration as our control case, and study the effects of anti-mitotic (AM), anti-angiogenic (AA), differentiation (Diff) and anti-GEC (AEC) therapies.

Transdifferentiated GEC form a network within the hypoxic core

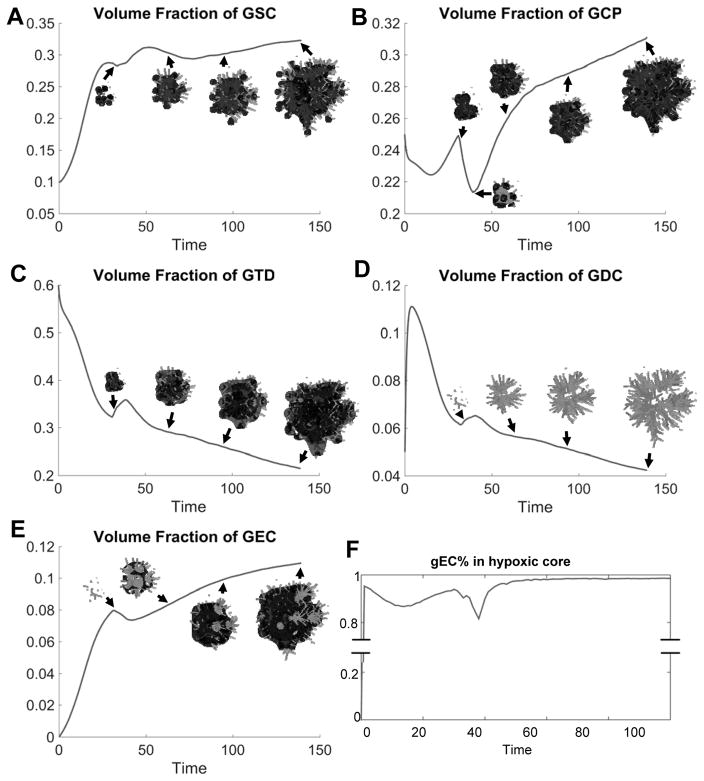

In Fig. 2A, the evolution of the control vascularized tumor is shown. GSC clusters emerge near the tumor boundary at early times as a result of a Turing-type pattern formation that generates regions of high W concentrations and GSC self-renewal. These GSC clusters generate invasive fingers with GSCs staying at finger tips and differentiated cells trailing behind, which has been observed clinically in Fig. 2E. Vessel sprouts form near the tumor boundary around T=30, grow and anastomose into functional vessels that supply nutrients to the tumor. Consequently, cell proliferation is enhanced and the tumor volume grows rapidly (Fig. 2C). The tumor volume doubles around T=35, consistent with clinical data (Fig. 2D). In the tumor interior, the vessel density and crosstalk signaling factor F concentration are highest, resulting in multiple new GSC clusters (Figs. 4A, 4G-4H). The volume fractions of each cell type are shown in Fig. 3. 2D slices and nutrient distribution are shown in Figs. 4A–4F.

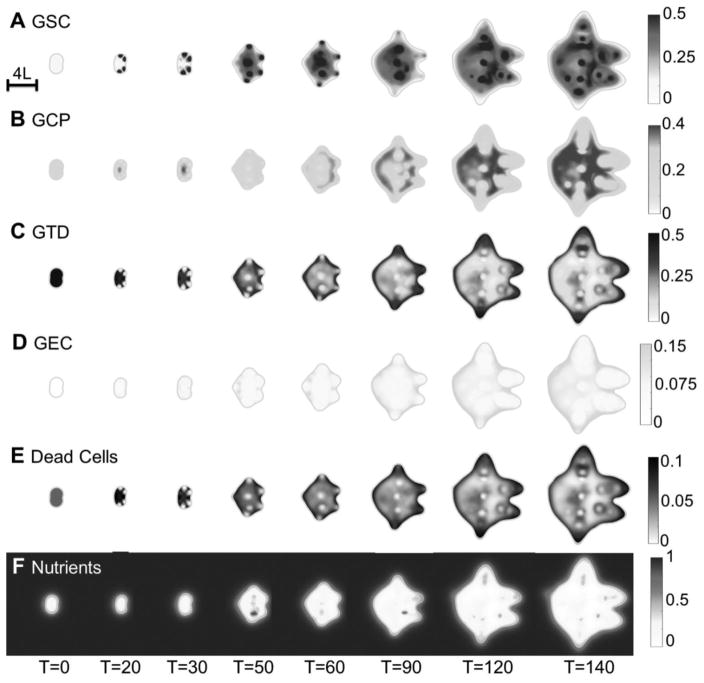

Fig. 4.

2D slices of the untreated vascular tumor in Fig. 2A. (A–H) Distributions of GSCs, GCPs, GTDs, GECs, dead cells, nutrients, vascular-produced GSC promoter (CF) and vessel density at the center of the tumor. Color version in SM. After the vasculature forms, functional vessels release nutrients in the tumor, and several new GSC clusters emerge at the tumor interior. In (D), GEC spontaneously form a network structure in the tumor, as seen in Fig. 2B.

Fig. 3.

Detailed analysis of the untreated vascular tumor in Fig. 2A. (A–E) Volume fraction of GSC, GCP, GTD, GDCs and GEC. Insets show the corresponding cell type. Color version in SM. (F) Most transdifferentiated GEC locate within the hypoxic core (nutrient level less than half of that in background vasculature).

As GSCs transdifferentiate, GECs are pushed into the tumor by the pressure generated by GSC proliferation at the tips, and form a connected network (Fig. 2B). Some GECs are also pushed to the tumor surface, away from the growing fingers, by transdifferentiation of GSCs in the tumor interior (Figs. 3E, 4A and 4D). Most of the GECs, however, are in the hypoxic region (nutrient level less than half of the host level), see Fig. 3F. This type of GEC spatial distribution was observed in (13), where xenograft GSC-containing human glioblastoma spheres implanted in mouse brains exhibited human CD31+ (endothelial) markers in the tumor core, while nearly all the CD31+ cells in tumor capsule were murine.

Anti-angiogenic and anti-mitotic therapies slows down tumor growth but increase invasiveness

Next, we investigate the effects of cancer therapies on the tumor in Fig. 5A. Traditional chemotherapy (temozolomide) has been extensively studied (34). Here, we use a simple model of the combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy by introducing an anti-mitotic (AM) agent released by the background vasculature that kills viable tumor cells proportionally to their mitosis rate, since tumor cell species may respond to therapy differently. We note that modeling the effects of chemo- and radio- therapy separately yields qualitatively similar results (not shown). Here, we do not account for reprogramming of differentiated GBM cells to GSCs that could occur during treatment (35) (see Discussion).

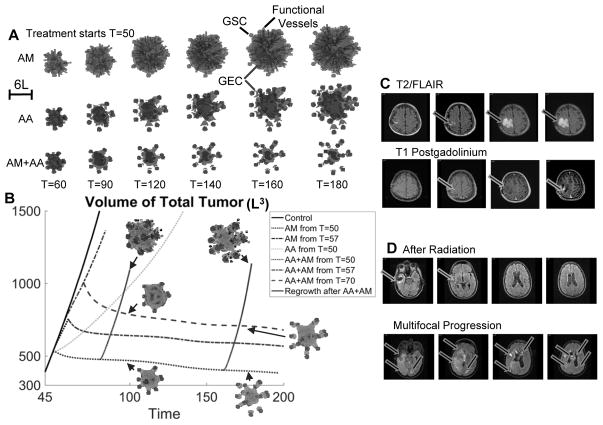

Fig. 5.

Anti-angiogenic and anti-mitotic therapy reduce tumor size but increase invasiveness. (A) Evolution of a tumor treated with anti-mitotic therapy (AM) and/or anti-angiogenic therapy (AA). Color version in SM. The tumor growth is identical to Fig. 2A until T=50. At T=50, the indicated therapy is applied. AM: the background vasculature releases an anti-mitotic agent that kills tumor cells proportionally to their mitosis rate. AA: the vasculature is completely removed and new vessels are not allowed to form. (B) Evolution of tumor volume in Fig. 2A (Control) and (A). Dotted line: AA, AM or AA+AM is applied from T=50. Dot-dashed line: tumor growth is identical to Control until T=57 (tumor surface area has increased by 25% from T=50), then AM or AA+AM is applied. Dashed line: tumor growth is identical to Control until T=57, then AM is applied until T=70 (tumor surface area increases 25% from T=57), then AA+AM is applied. Solid line: tumor regrowth after AA+AM is removed. Insets show tumor cells and vasculature after regrowth, compared to those treated with continued AA+AM. (C) Anti-angiogenic therapy increases invasion. Left column: minimal residual after surgery; second column: progression after radiation and temozolomide. Third column: progression after bevacizumab. Right column: progression after bevacizumab. (D) Multifocal, dramatic progression in a patient who has received both bevacizumab and cytotoxic chemotherapy (irinotecan).

From T=0 to T=50, the growth is identical to the Control in Fig. 2A. After T=50, AM is applied continuously. The tumor still grows rapidly in size (Fig. 5A, top), although slower than Control, since the vasculature continues to support the GSC cluster at the center. The volume fractions of each cell type are shown in Fig. S11 in SM.

In addition, we target GSC-vasculature crosstalk using an extreme scenario in which the vasculature is removed completely from the tumor and the microenvironment, and new vessels are not allowed to form. When this anti-angiogenic therapy (AA, e.g. bevacizumab) is applied continuously from T=50, the overall volume grows at a substantially slower rate (Fig. 5B). The growth is driven by the GSC clusters at the finger tips, which are less affected by the removal of the vessels. Consequently, the fingers continue elongating and penetrating the host. Thus, AA considerably increases tumor invasiveness (Fig. 5A, middle), consistent with experimental and clinical findings (Fig. 5C and (19)). The tumor shape factor (dimensionless measure of deviation from a sphere) is significantly increased (Fig. S11F in SM). The GSC cluster at the center persists after the removal of vessels, despite the loss of positive feedback from the crosstalk. This is because these GSCs are self-sustaining but proliferate at low rates due to the lack of nutrients (Figs. S9F and S11 in SM). Consequently, the GSC fractions are only reduced marginally by AA (Fig. S11A in SM). The volume fractions of each cell type are shown in Fig. S11 and 2D slices are shown in Figs. S8–S10 in SM.

The FDA-approved, standard-of-care treatment for newly-diagnosed GBM patients (Fig. 1B) consists of surgery followed by radiation and chemotherapy (temozolomide) for six weeks, and continued with temozolomide treatment for 6–12 cycles (months) or until disease progression (PD) where the tumor surface area increases by 25%. Then, bevacizumab is applied as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy until PD. Here, we first simulate the case in which the combination of AM and AA is started from T=50 (which we consider to be after surgery). Correspondingly, the tumor volume decreases (Fig. 5B, dotted line), which was also seen in (34) where anti-angiogenic and cytotoxic therapy effectively reduces tumor mass. However, we observe that the fingers continue to grow and the finger tips detach from the tumor leading to the formation of multifocal tumors (Fig. 5A, bottom), which is consistent with experimental observations (Fig. 5D). This occurs because the finger necks tend to be populated by the more differentiated cells that are more susceptible to AM. Note that each new microtumor contains an active GSC niche indicating malignant invasion. Finally, the tumor volume tends to stabilize and the tumor cannot be eradicated. In fact, the tumor regrows if the treatment is removed, and the tumor volume grows rapidly (nearly at the same speed as Control) once the vasculature forms (Fig. 5B, solid line).

Analogously, when AM+AA is applied from disease progression after AM treatment (T=57), the tumor volume also decreases in time (Fig. 5B, dot-dashed line). However, the tumor volume stabilizes at a higher level than when AM+AA is applied from T=50. When AM+AA is applied from T=70, after AM treatment from disease progression until another 25% increase in surface area occurs (Fig. 5B, dashed line), the tumor volume decreases and stabilizes at an even higher level. These results suggest that AM+AA combination could be more effective if applied right after surgery, although in all cases these treatments increase tumor invasiveness and could potentially generate multifocal, malignant tumors.

Anti-GSC therapies reduce tumor invasiveness

We have demonstrated that AA and AM could enhance tumor invasion. Since GSC clusters near the tumor boundary drive invasive fingering, we now target GSCs to reduce invasiveness (and tumor size). Differentiation therapies have been investigated in both experiments (36) and simulations (4). Here, we assume that the background vasculature continuously releases GSC differentiation promoter T1. We combine this differentiation therapy (Diff) with AA, which has been shown to slow down tumor growth, and present the results in Fig. 6A–D (the volume fractions of the different cell types, GSC self-renewal fraction and shape factors are shown in Figs. S13 and S15 in SM). When AA+Diff is applied continuously from T=50, T1 diffuses into the tumor and reduces the GSC self-renewal fraction p0 (Fig. 6D). This decreases the GSC fraction (Fig. 6C) and results in the retraction of the fingers and a reduction in invasiveness (Fig. 6A). The tumor also shrinks because the GCPs cannot self-renew (note that we have assumed ) and differentiate into postmitotic GTDs that apoptose. This behavior was observed in both simulations, where tumors treated with large amounts of differentiation promoters are less invasive (4), and experiments where stem-like glioma cells cultured under differentiation conditions invade less aggressively (36) (Fig. 6E). We note that the differentiation therapy needs to be sufficiently large to control tumor invasion (see Fig. S16 in SM). Similar effects are observed when the GSC self-renewal promoter is inhibited (see Fig. S17 in SM).

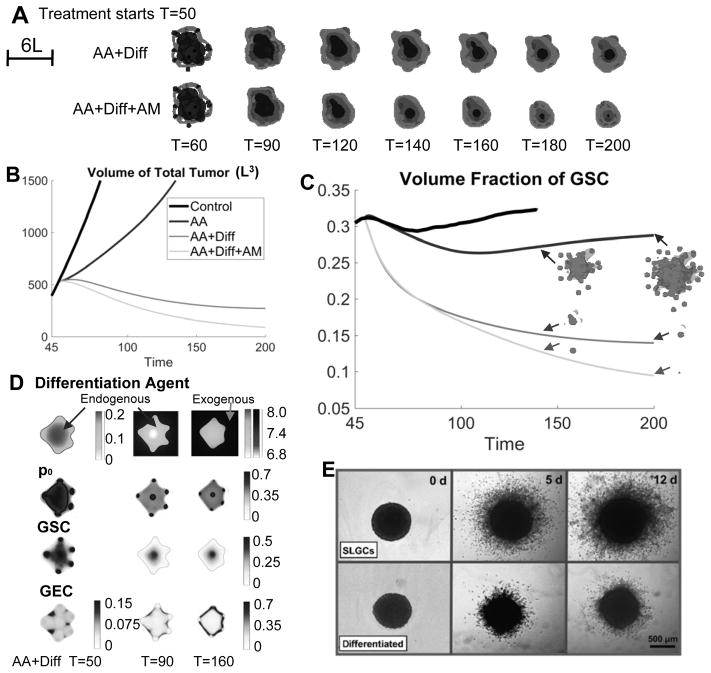

Fig. 6.

Differentiation therapy reduces both tumor volume and invasion. (A) Evolution of tumors treated with anti-angiogenic (AA) and differentiation therapy (Diff), and/or anti-mitotic therapy (AM). The growth is identical to Fig. 2A until T=50. At T=50, the indicated therapy begins to apply. Color version in SM. (B–C) Evolution of tumor volumes and GSC fractions of tumors in Fig. 2A and (A). Insets in (C) show the distributions of GSC (dark gray) in the tumor (gray). (D) 2D slices at the center of computational domain, of the differentiation agent, GSC self-renewal fraction (p0), GSC and GEC in the tumor treated by AA+Diff. (E) Differentiation therapy reduces the invasiveness of stem-like glioma cells (SLSC), adapted from Fig. 4 in (36) (“Differentiation therapy exerts antitumor effects on stem-like glioma cells” by Campos B et al., Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:2715-28). Reprinted with permission.

In Fig. 6A (top), the GECs begin to cover the tumor boundary as a result of enhanced GSC differentiation. These GECs release crosstalk factors that support GSC self-renewal and proliferation. In particular, p0>0.5 at the tumor center (Fig. 6D). Consequently, the GSC cluster at the center persists, and the tumor volume stabilizes (Fig. 6B). When the tumor is treated additionally by AM (AA+Diff+AM), the GECs still cover the tumor boundary and support GSCs at the center (Fig. 6A, bottom). The tumor volume also stabilizes at a late time even though the tumor is smaller (Fig. 6B; Figs. S14–S15 in SM). This suggests that novel cancer therapies targeting GECs or transdifferentiation should be included in combination treatments for GBM, to eradicate the tumor.

Combinatorial therapies targeting transdifferentiated GECs reduce both tumor size and invasiveness

We now combine the previously studied therapies with an anti-GEC therapy (AEC) that kills transdifferentiated GECs. When the tumor is treated with AA+AM+AEC, the tumor surface is no longer covered by GECs (Fig. 7A top, in contrast to Fig. 5A) and tumor volume is further decreased. However, the tumor becomes highly invasive and multifocal since cells at the finger necks are killed, which occurs even earlier than AA+AM because there are far fewer GECs present to maintain the GSCs. The tumor cannot be eradicated (Fig. 7B, dotted line; Figs. S18 and S21 in SM). In contrast, when AA+Diff is combined with AEC, GECs no longer support GSCs at the tumor center. Consequently, this GSC cluster is rapidly shrunk by differentiation (Fig. 7A, middle), and the tumor volume is effectively reduced, but the tumor is not eradicated (Fig. 7B; Figs. S12 and S21 in SM). Further, when this treatment is combined with AM (Fig. 7A, bottom; Figs. S20 and S21 in SM), the tumor is eradicated if the treatment lasts through T=200 (Fig. 7B, dashed line). Note that the tumor is also eradicated if the treatments start at disease progression (T=57) (Fig. 7B dot-dashed line).

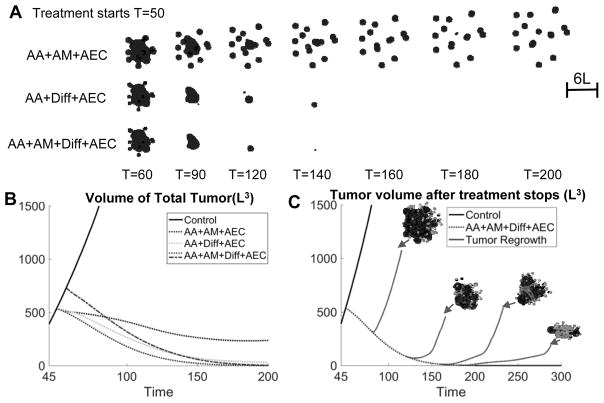

Fig. 7.

Combinatorial therapies that can effectively reduce tumor size and invasiveness, and eventually kill the tumor. (A) Evolution of tumors treated by anti-angiogenic (AA) and anti-GEC therapy (AEC), combined with anti-mitotic therapy (AM) and/or differentiation (Diff) therapies. Color version in SM. The growth is identical to Fig. 2A until T=50. At T=50, the indicated therapy is applied. AA+AM+AEC reduces growth but enhances invasiveness, while AA+Diff+AEC reduces both size and invasiveness. AA+AM+Diff+AEC for sufficient time (T=200) eventually eliminates the tumor. (B) Evolution of total volumes of tumors in Fig. 2A and (A). Dotted line: continuous treatment from T=50. Dot-dashed line: tumor growth is identical to Control until T=57 followed by continuous treatment. (C) Evolution of tumor volume after the combined treatment (AA+AM+Diff+AEC) stops at T=80, 120, 160, 180 or 200, and the tumor vasculature is allowed to reform. Dotted line: continuous treatment from T=50; solid line: tumor regrowth after the treatment stops. Insets show the vasculature and tumor after regrowth. When AA+AM+Diff+AEC is applied through T=200, the tumor is removed and does not regrow even after the treatment stops.

We also investigate the possibility of tumor recurrence if the AA+AM+Diff+AEC combination treatment is stopped due to physician concerns or patient’s preference. When the combined therapy is applied from T=50 but stops earlier than T=200, the tumor recurs and rate of volume growth is nearly the same as that of Control once the vasculature forms (Fig. 7C, solid line). However, if the treatment stops at T=200 when the GSCs have been decreased to a sufficiently low level so as to induce an Allee effect (37), the tumor does not regrow. Therefore, the results suggest that a combination of anti-angiogenic, anti-mitotic, differentiation and anti-GEC therapy greatly reduces tumor growth and invasion, and could eradicate the tumor without recurrence when the treatment is stopped – achieving long-lasting remission.

Discussion

We have used a hybrid continuum-discrete multispecies model to simulate glioma growth and response to therapies. Our model accounts for glioma stem (GSC), committed progenitor (GCP), terminally differentiated (GTD) and dead cells (DC) as well as vascular endothelial cells (GEC) that arise from transdifferentiation of GSCs. We also account for angiogenesis from the pre-existing vasculature in the tumor microenvironment, and crosstalk between the different cell types via soluble signaling factors. Tumor cells in the hypoxic core positively feedback to the vessel network through VEGF, while tumor cell proliferation negatively regulates the vasculature through pressure. Nutrient delivery from the vasculature provides positive feedback on cancer cell proliferation. Both GECs and vascular endothelial cells arising from the pre-existing vasculature release factors that promote GSC self-renewal and proliferation and help to maintain a stem cell niche.

As expected, we found that conventional anti-angiogenic therapy (e.g., bevacizumab) and anti-mitotic therapy (e.g., combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy (temozolomide)) both inhibited tumor growth, by either inducing hypoxia to reduce cell proliferation and induce cell death or by directly killing viable tumor cells. However, consistent with previous modeling work (see (1) and the references therein), the microenvironment heterogeneity induced by these therapies applied alone or concurrently enhanced tumor invasiveness. The removal of vasculature makes the tumor invade aggressively because the GSCs at the tumor boundary are still able to access nutrients from the pre-existing vasculature and hence are still able to proliferate, creating long invasive fingers. This increased invasiveness was not a result of explicit changes in cell phenotypes, although the death of more differentiated cells in the tumor interior does relieve the stem cells somewhat from negative feedback regulation (e.g., from T1). Experiments have suggested that intense hypoxia following anti-angiogenic treatments can select for invasive cell phenotypes as an adaptive response to hypoxia due to lack of vessels (19). In addition, new data suggest that long-term temozolomide treatment induces chromosomal instability, which in turn leads to potential increases in invasion and migration (38). Including such additional phenotypic changes in our model, as well as therapy-induced reprogramming of differentiated GBM cells to GSCs (35), would only add to the invasiveness we observed.

We note that the anti-angiogenic therapy in this paper was implemented as an extreme case, where the vasculature is completely removed and no vessels can form thereafter. However, less drastic applications of anti-angiogenic therapy can normalize the vasculature in the tumor microenvironment, rather than removing it entirely, and actually improve the flow of blood and blood-borne agents (e.g., nutrients and chemotherapy drugs) to the tumor (39) thereby increasing the efficacy of treatment. In addition, an increased supply of nutrients to the tumor may help to control invasiveness. Investigation of these effects is left to future study.

Because GSC patterning plays an important role in tumor invasion driving invasive fingering, and actively contributing to glioma chemo- and radiotherapy resistance, we investigated anti-GSC therapies that inhibit GSC self-renewal (e.g. by introducing differentiation promoters or by blocking self-renewal promoters) to disrupt invasion. We found that under this treatment invasive fingers were eradicated and tumor sizes were effectively reduced by terminal cell apoptosis. This effect was observed in (36), where stem-like glioma cells cultured on differentiation-promoting (ATRA-containing) medium invade less aggressively. Moreover, BMP-4 treatment also showed pro-differentiation effects and reduced infiltrating tumor cells into the host, which suppressed the tumorigenicity of the glioblastoma (40). Inhibiting the Shh pathway in glioma cell cultures and murine models has also been shown to significantly deplete GSCs from tumor spheres and decrease growth rates of GBM tumors (41).

Another pathway closely involved in GSC regulation is the Notch pathway, and inhibiting this pathway has been found to reduce GSC populations as well as tumor volumes in animal models (42). The PDGFRα pathway has been found to regulate invasive fingering into normal brain tissue (43), and inhibiting this pathway reduces invasiveness by inducing GSC apoptosis (18) and possibly off-target effects. Inhibiting Wnt signaling (a self-renewal promoter) also decreases tumor growth and tumorigenicity (44).

It is thought that anti-angiogenic therapies block the GSC-vasculature crosstalk, but fail to affect transdifferentiated GECs, which are not VEGF-dependent (14). Since GECs positively regulate GSC proliferation and self-renewal, it is hypothesized that GECs are involved in GBM resistance to traditional cancer therapies (45). Indeed, we found that during therapy, GECs protect the GSCs and prevent eradication of the tumor. However, when anti-GEC treatment is combined with anti-mitotic and anti-angiogenic therapies, we predict increased tumor invasion. The GECs are shown to support finger-tumor connections, and killing these GECs potentially promotes the development of multifocal tumors, and stopping the GEC treatments causes almost immediate tumor progression.

Our results suggest that combined therapies targeting the vasculature, GSCs and GECs are highly synergistic. Anti-angiogenic therapy inhibits tumor cell proliferation and blocks the positive feedback from the vasculature to GSCs. Anti-GSC therapies are vital for controlling tumor invasion. Treating GECs further reduces tumor sizes by targeting GSCs indirectly. When combined with anti-mitotic therapies (chemo- and radio-) these combinatorial treatments can eradicate the tumor by the time treatment is ended. When reprogramming of GBM differentiated cells into GSCs is considered, anti-reprogramming therapies might also be required in the combinatorial treatments to eradicate the tumor (46). However, if the reprogramming rates are sufficiently small, our proposed combination strategy should still be effective. This is confirmed by preliminary simulations that combine a spatial extension of the model in (46), which accounts for the reprogramming-promoter survivin and its inhibitor YM155, with the multispecies model presented here (results not shown). A complete study will be presented in future work.

To test our predictions in the clinic, the presence of GECs in primary human tumors needs to be established and anti-GEC treatments need to be developed. Regarding the former, there is some controversy as some authors have claimed that GEC are a rare population of cells in glioma in humans (47) and others have found that transdifferentiation of GSCs may result in pericytes and not GECs (16). Nevertheless, data on transdifferentiation in human xenografts in mouse models is compelling and further research in this direction is needed. Regarding an anti-GEC treatment, one candidate is potentially an EGFR blocker. As discussed earlier, EGFR is involved in proliferation, differentiation, migration and angiogenesis regulation in many glioma tumors and the EGFR mutation is also present in the GECs. Therefore, blocking EGFR could effectively target GECs, among other targets.

While the first generation of EGFR inhibitors did not improve clinical outcomes by themselves, they significantly impair tumor aggressiveness in experimental glioma models when combined with other therapies such as chemotherapy, differentiation (48), anti-angiogenic therapies (49) or signaling pathway blockage (2). The latest generation of EGFR inhibitors, such as irreversible tyrosine kinase inhibitors (dacomitinib (24)) effectively reduce the tumor volume in animal models by decreasing the GSC population by enhancing differentiation (24). Therefore, we suggest that a brain-penetrant EGFR inhibitor potentially matches the need for a differentiation promoter, anti-GSC and anti-GEC agent, which could be combined in future clinical trials with both anti-angiogenic therapy and chemotherapy. However, experiments have shown that dacomitinib has to be administered continuously since the tumor regrows whenever the treatment is stopped (24). This is consistent with our results if the therapy cocktail is not correctly structured (e.g., need AA+AM+Diff+AEC) and the therapy is not applied long enough.

In summary, we propose that the next generation of clinical trials can repurpose drugs that are already known to affect glioma growth, and which display low toxicity profiles, to test the predictions made here. We are planning to conduct at our institution (University of California, Irvine) a clinical trial of a combination regimen including temozolomide, bevacizumab, retinoic acid derivatives and a clinically-available, brain penetrant EGFR inhibitor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work is supported in part by the National Science Foundation Division of Mathematical Sciences (H. Yan, J.S. Lowengrub), a UC-MEXUS fellowship (M. Romero-López), a Miguel Velez fellowship at UCI (M. Romero-López), the National Institutes of Health through grants U54CA143907 (H.B. Frieboes), R01HL60067 and R01CA180122 (C.C.W. Hughes), P50GM76516 for the Center of Excellence in Systems Biology at the University of California, Irvine, and the National Institute for Neurological Diseases and Stroke Award (NINDS/NIH) NS072234 (D.A. Bota). J.S. Lowengrub, D.A. Bota and C.C.W. Hughes receive support from the Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center at University of California, Irvine through an NCI Center Grant Award, P30CA062203.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Frieboes HB, Jin F, Chuang YL, Wise SM, Lowengrub JS, Cristini V. Three-dimensional multispecies nonlinear tumor growth-II: Tumor invasion and angiogenesis. J Theor Biol. 2010;264:1254–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul I, Bhattacharya S, Chatterjee A, Ghosh MK. Current Understanding on EGFR and Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling in Glioma and Their Possible Crosstalk. Genes Cancer. 2013;4:427–46. doi: 10.1177/1947601913503341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee Y, Lee JK, Ahn SH, Lee J, Nam DH. WNT signaling in glioblastoma and therapeutic opportunities. Lab Invest. 2016;96:137–50. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youssefpour H, Li X, Lander AD, Lowengrub JS. Multispecies model of cell lineages and feedback control in solid tumors. Journal of theoretical biology. 2012;304:39–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meulmeester E, Ten Dijke P. The dynamic roles of TGF-beta in cancer. J Pathol. 2011;223:205–18. doi: 10.1002/path.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, Hao Y, Li Z, Hjelmeland AB, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7843–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan HR-LM, Frieboes HB, Hughes CCW, Lowengrub JS. Multiscale Modeling of Glioblastoma Suggests that the Partial Disruption of Vessel/Cancer Stem Cell Crosstalk Can Promote Tumor Regression Without Increasing Invasiveness. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2017;64:538–48. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2016.2615566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Fulop J, Liu M, Blanda R, Kromer C, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2008–2012. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(Suppl 4):iv1–iv62. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lathia JD, Mack SC, Mulkearns-Hubert EE, Valentim CL, Rich JN. Cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1203–17. doi: 10.1101/gad.261982.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, Hogg TL, Fuller C, Hamner B, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charles N, Ozawa T, Squatrito M, Bleau AM, Brennan CW, Hambardzumyan D, et al. Perivascular nitric oxide activates notch signaling and promotes stem-like character in PDGF-induced glioma cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:141–52. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Infanger DW, Cho Y, Lopez BS, Mohanan S, Liu SC, Gursel D, et al. Glioblastoma stem cells are regulated by interleukin-8 signaling in a tumoral perivascular niche. Cancer Res. 2013;73:7079–89. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricci-Vitiani L, Pallini R, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Invernici G, Cenci T, et al. Tumour vascularization via endothelial differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Nature. 2010;468:824–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soda Y, Marumoto T, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Soda M, Liu F, Michiue H, et al. Transdifferentiation of glioblastoma cells into vascular endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4274–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emlet DR, Gupta P, Holgado-Madruga M, Del Vecchio CA, Mitra SS, Han SY, et al. Targeting a glioblastoma cancer stem-cell population defined by EGF receptor variant III. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1238–49. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng L, Huang Z, Zhou W, Wu Q, Donnola S, Liu JK, et al. Glioblastoma stem cells generate vascular pericytes to support vessel function and tumor growth. Cell. 2013;153:139–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field KM, Jordan JT, Wen PY, Rosenthal MA, Reardon DA. Bevacizumab and glioblastoma: scientific review, newly reported updates, and ongoing controversies. Cancer. 2015;121:997–1007. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, Takeda T, Okuyama H, Vinals F, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:220–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruceru ML, Neagu M, Demoulin JB, Constantinescu SN. Therapy targets in glioblastoma and cancer stem cells: lessons from haematopoietic neoplasms. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17:1218–35. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karsy M, Albert L, Tobias ME, Murali R, Jhanwar-Uniyal M. All-trans retinoic acid modulates cancer stem cells of glioblastoma multiforme in an MAPK-dependent manner. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4915–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takebe N, Harris PJ, Warren RQ, Ivy SP. Targeting cancer stem cells by inhibiting Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:97–106. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth P, Weller M. Challenges to targeting epidermal growth factor receptor in glioblastoma: escape mechanisms and combinatorial treatment strategies. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(Suppl 8):viii14–9. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zahonero C, Aguilera P, Ramirez-Castillejo C, Pajares M, Bolos MV, Cantero D, et al. Preclinical Test of Dacomitinib, an Irreversible EGFR Inhibitor, Confirms Its Effectiveness for Glioblastoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1548–58. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan Y, Xu X, Xie C. EGFR-TKI therapy for patients with brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of published data. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:2075–84. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S67586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altrock PM, Liu LL, Michor F. The mathematics of cancer: integrating quantitative models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:730–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc4029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson PR, Juliano J, Hawkins-Daarud A, Rockne RC, Swanson KR. Patient-specific mathematical neuro-oncology: using a simple proliferation and invasion tumor model to inform clinical practice. Bull Math Biol. 2015;77:846–56. doi: 10.1007/s11538-015-0067-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martirosyan NL, Rutter EM, Ramey WL, Kostelich EJ, Kuang Y, Preul MC. Mathematically modeling the biological properties of gliomas: A review. Math Biosci Eng. 2015;12:879–905. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2015.12.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engwer C, Hillen T, Knappitsch M, Surulescu C. Glioma follow white matter tracts: a multiscale DTI-based model. J Math Biol. 2015;71:551–82. doi: 10.1007/s00285-014-0822-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jbabdi S, Mandonnet E, Duffau H, Capelle L, Swanson KR, Pelegrini-Issac M, et al. Simulation of anisotropic growth of low-grade gliomas using diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:616–24. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Painter KJ, Hillen T. Mathematical modelling of glioma growth: the use of Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) data to predict the anisotropic pathways of cancer invasion. J Theor Biol. 2013;323:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leder K, Pitter K, Laplant Q, Hambardzumyan D, Ross BD, Chan TA, et al. Mathematical modeling of PDGF-driven glioblastoma reveals optimized radiation dosing schedules. Cell. 2014;156:603–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neal ML, Trister AD, Cloke T, Sodt R, Ahn S, Baldock AL, et al. Discriminating survival outcomes in patients with glioblastoma using a simulation-based, patient-specific response metric. PLoS One. 2013;8:e51951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folkins C, Man S, Xu P, Shaked Y, Hicklin DJ, Kerbel RS. Anticancer therapies combining antiangiogenic and tumor cell cytotoxic effects reduce the tumor stem-like cell fraction in glioma xenograft tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3560–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vlashi E, Pajonk F. Cancer stem cells, cancer cell plasticity and radiation therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;31:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campos B, Wan F, Farhadi M, Ernst A, Zeppernick F, Tagscherer KE, et al. Differentiation therapy exerts antitumor effects on stem-like glioma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2715–28. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konstorum A, Hillen T, Lowengrub J. Feedback Regulation in a Cancer Stem Cell Model can Cause an Allee Effect. Bull Math Biol. 2016;78:754–85. doi: 10.1007/s11538-016-0161-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stepanenko AA, Andreieva SV, Korets KV, Mykytenko DO, Baklaushev VP, Huleyuk NL, et al. Temozolomide promotes genomic and phenotypic changes in glioblastoma cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2016;16:36. doi: 10.1186/s12935-016-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang Y, Stylianopoulos T, Duda DG, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Benefits of vascular normalization are dose and time dependent--letter. Cancer Res. 2013;73:7144–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piccirillo SG, Reynolds BA, Zanetti N, Lamorte G, Binda E, Broggi G, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins inhibit the tumorigenic potential of human brain tumour-initiating cells. Nature. 2006;444:761–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bar EE, Chaudhry A, Lin A, Fan X, Schreck K, Matsui W, et al. Cyclopamine-mediated hedgehog pathway inhibition depletes stem-like cancer cells in glioblastoma. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2524–33. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hovinga KE, Shimizu F, Wang R, Panagiotakos G, Van Der Heijden M, Moayedpardazi H, et al. Inhibition of notch signaling in glioblastoma targets cancer stem cells via an endothelial cell intermediate. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1019–29. doi: 10.1002/stem.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao Y. Multifarious functions of PDGFs and PDGFRs in tumor growth and metastasis. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:460–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gurney A, Axelrod F, Bond CJ, Cain J, Chartier C, Donigan L, et al. Wnt pathway inhibition via the targeting of Frizzled receptors results in decreased growth and tumorigenicity of human tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11717–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120068109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borovski T, Beke P, van Tellingen O, Rodermond HM, Verhoeff JJ, Lascano V, et al. Therapy-resistant tumor microvascular endothelial cells contribute to treatment failure in glioblastoma multiforme. Oncogene. 2013;32:1539–48. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhodes A, Hillen T. Mathematical Modeling of the Role of Survivin on Dedifferentiation and Radioresistance in Cancer. Bull Math Biol. 2016;78:1162–88. doi: 10.1007/s11538-016-0177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez FJ, Orr BA, Ligon KL, Eberhart CG. Neoplastic cells are a rare component in human glioblastoma microvasculature. Oncotarget. 2012;3:98–106. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stockhausen MT, Kristoffersen K, Stobbe L, Poulsen HS. Differentiation of glioblastoma multiforme stem-like cells leads to downregulation of EGFR and EGFRvIII and decreased tumorigenic and stem-like cell potential. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:216–24. doi: 10.4161/cbt.26736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabernero J. The role of VEGF and EGFR inhibition: implications for combining anti-VEGF and anti-EGFR agents. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:203–20. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaijun Di MEL, Daniela A. Bota. TRIM11 is over-expressed in high-grade gliomas and promotes proliferation, invasion, migration and glial tumor growth. Oncogene. 2013;32:5038–47. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.