Abstract

This perspective examines frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs) in the context of heterolytic cleavage of H2 by transition metal complexes, with an emphasis on molecular complexes bearing an intramolecular Lewis base. FLPs have traditionally been associated with main group compounds, yet many reactions of transition metal complexes support a broader classification of FLPs that includes certain types of transition metal complexes with reactivity resembling main group-based FLPs. This article surveys transition metal complexes that heterolytically cleave H2, which vary in the degree that the Lewis pairs within these systems interact. Many of the examples include complexes bearing a pendant amine functioning as the base with the metal functioning as the hydride acceptor. Consideration of transition metal compounds in the context of FLPs can inspire new innovations and improvements in transition metal catalysis.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘Frustrated Lewis pair chemistry’.

Keywords: heterolytic, hydrogen, cleavage, frustrated, hydride, hydrogenase

1. Introduction

The H–H bond of dihydrogen is the simplest covalent bond, yet its reactivity offers remarkable diversity. Breaking the H–H bond is the key to the utility of H2. It was long thought that metals were required to cleave the H–H bond under mild conditions, so it was a startling and fascinating discovery when Stephan and co-workers [1] reported that H2 reacts at room temperature with ‘frustrated Lewis pairs’ (FLPs) of phosphorus and boron compounds. This FLP reactivity can be described generally as shown in equation (1.1). A reaction thought to reside only in the domain of transition metal complexes was accomplished with main group compounds, spawning a new topic of inorganic chemistry, many examples of which are described in this theme issue.

| 1.1 |

As main group FLP chemistry was burgeoning, an insightful perspective by Flynn & Wass [2] called attention to the role of transition metal complexes in reactions that proceed by FLP pathways. They called attention to the connection of metal-based FLP chemistry to the more broadly defined topic of metal–ligand cooperation (bifunctional catalysis), where the two sites of cooperation are metal-based and ligand-based [3–5].

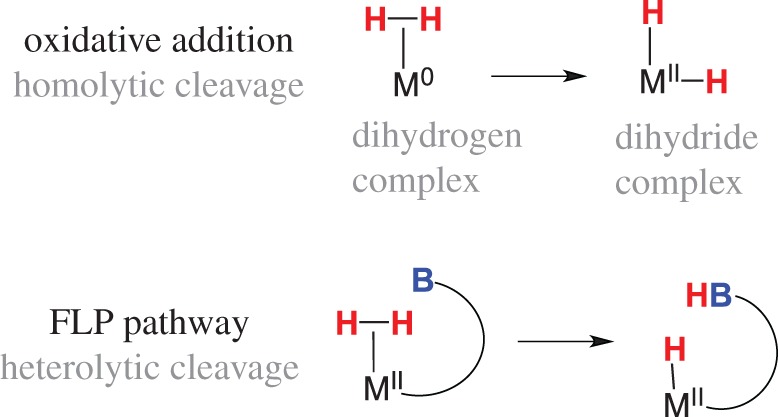

Many transition metal reactions with dihydrogen are proposed to proceed through an M(H2) dihydrogen adduct, though in many cases the dihydrogen complex is not directly observed. The heterolytic cleavage of H2 contrasts with the homolytic cleavage of H2 traditionally observed for metal complexes, as generalized in figure 1, which also indicates the changes in formal oxidation state at the metal centre. By contrast, main group intermolecular FLPs have been proposed to heterolytically cleave H2 through an ‘encounter complex’ where the Lewis acid and Lewis base are in close proximity, but non-bonding, and H2 is poised between the pair prior to heterolysis. For the prototypical FLP systems such as P(Mes)3/B(C6F5)3, computational studies have considered whether the reaction occurs by electron transfers [6] or by the generation of a strong electric field that leads to the hydride transfer to B and proton transfer to P [7]. Recent density functional theory (DFT) metadynamics studies reported evidence for polarization of H2 followed by rate-determining hydride transfer to B and proton transfer to P [8].

Figure 1.

Homolytic and heterolytic cleavage of dihydrogen by a transition metal. (Online version in colour.)

This perspective article focuses on the heterolytic cleavage of H2 into a proton and hydride by FLPs, generally with a transition metal as the hydride acceptor and an organic base, often an amine, as the proton acceptor. The heterolytic cleavage of H2 is critically important in several contexts. Many hydrogenations of C=O bonds require heterolytic cleavage of H2. Heterolytic cleavage of H2 is entailed in the oxidation of hydrogen in biological systems such as hydrogenase, and in synthetic catalysts for oxidation of hydrogen used in energy conversion reactions. The now-familiar nomenclature of ‘frustrated Lewis pairs’ is an apt description of the heterolytic cleavage of the H–H bond of dihydrogen that had been observed in many reactions of transition metals for many years, as it helps to categorize that type of reaction, and to recognize its prevalence and importance.

Most examples discussed in this perspective are those in which the metal and the base are present in the same metal complex, such that the heterolytic cleavage of H2 is intramolecular. A few examples will be cited in the context of model studies of hydrogenases, in which an exogenous base deprotonates a dihydrogen complex. Mechanistic pathways for H2 heterolysis in metal FLP systems vary in the degree that H2 coordinates to the metal centre. This perspective provides both examples that form discrete H2 adducts and examples that directly cleave H2 without evidence for an intermediate adduct. Deprotonation of H2 ligands on metals by exogenous bases has been extensively studied [9], and that topic will not be covered in detail in this perspective.

2. Stoichiometric reactivity

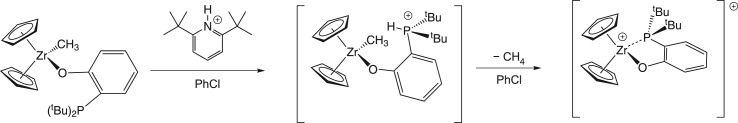

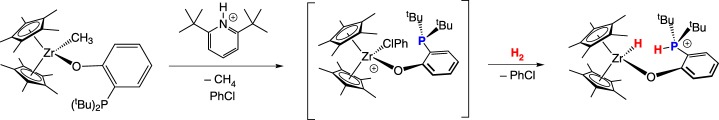

(a). Zr–phosphane frustrated Lewis pairs

An appropriate comparison of traditional main group FLP systems to metal-based complexes are those based on zirconium reported by Wass and co-workers [10], exemplifying the chemical similarity that can arise between these two families of FLPs. Protonation of the methyl complex Cp2Zr(O(C6H4)PtBu2)Me first occurs at phosphorus, as determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Elimination of methane generates a Zr–P adduct (scheme 1) with an elongated Zr–P bond. The C5Me5 derivative, apparently too sterically encumbered, does not form a Zr–P bond, but instead forms an adduct with the chlorobenzene solvent (scheme 2). This frustrated Lewis acidic zirconium and Lewis basic phosphorus pair in [Cp*2Zr(ClPh)(O(C6H4)P(tBu)2)]+ rapidly cleaves H2 heterolytically in solution, presumably with prior dissociation of the chlorobenzene ligand (scheme 2). The Cp derivative is unreactive towards H2 under similar conditions.

Scheme 1.

Scheme 2.

(Online version in colour.)

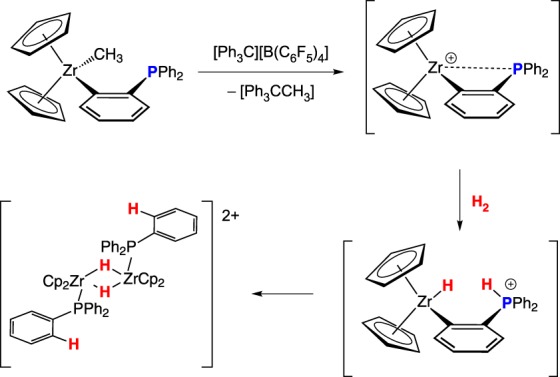

Erker and co-workers [11] found that intramolecular Zr–P bond formation can be disfavoured in Cp derivatives by the strain induced in the resulting metallacycle. Following reaction of the aryl zirconium methyl complex Cp2Zr(κ1-C6H4PPh2)Me with Ph3C+, the FLP cation [Cp2Zr(C6H4PPh2)]+ heterolytically cleaves H2 in solution, generating a proposed transient zirconium hydrido-phosphonium species, which converts to the observed product [Cp2Zr(H)PPh3]2[B(C6F5)4]2 (scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

(Online version in colour.)

(b). Metal–boron and metal–aluminium adducts

Boron is nearly ubiquitous in main group FLPs and is also represented in transition metal FLP systems. As there is a metal–boron interaction in these complexes, it may be questioned if they are properly classified as ‘frustrated’, but the reactivity with H2 shows they do exhibit characteristic FLP reactions. In most metal-containing FLPs, the metal serves as the Lewis acid and a heteroatom is the Lewis base. Metal–borane complexes provide an example where the opposite reactivity has been proposed, with the metal serving as a Lewis base while the boron functions as a Lewis acid. The activity in main group FLPs is sensitive to the degree to which the cooperative acid–base pair interact. When a discrete LA–LB bond is present, they are often inactive for the heterolytic cleavage of hydrogen, though Stephan and co-workers [12] discovered an unusual reaction in which a weak adduct of (Et2O)B(C6F5)3 cleaves H2 and catalyses the hydrogenation of C=C bonds. The strength of acid–base interaction, and consequently FLP activity, can be modulated using electronic effects, as reported by Erker and co-workers [13,14].

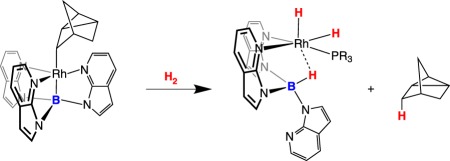

Covalent bonding between a transition metal and a borane does not quench the H2 heterolysis cooperativity. It is not clear whether or not, or to what degree, the boron-containing ligand dissociates prior to H2 heterolysis, nor the role of potential metal–dihydrogen adducts. Owen and co-workers [15–17] reported rhodium complexes in which a metal–boron bond is heterolytically cleaved by dihydrogen. The rhodium complex shown in equation (2.1) reacts with H2, generating a rhodium dihydride borohydrido species, eliminating nortricyclene as follows:

|

2.1 |

Peters and co-workers reported heterolytic cleavage of H2 using phosphano-borane complexes of the first-row metals nickel [18] and iron [19]. In the Ni complex shown in equation (2.2), a weak bond between the arene and nickel is displaced rapidly upon reaction with H2. Their interpretation of this unusual reaction is that H2 adds across the Ni–B bond whereby the Ni centre is protonated and the borane accepts the hydride. The reaction of their Fe complex with H2 (equation (2.3)) involves displacement of an N2 ligand. The reaction is described similarly to that of their nickel complex, with H2 inserting into the Fe–B bond, suggesting dissociation is not required in either case. Such a proposal seems reasonable, given that the chelating nature of the boratrane ligand would disfavour dissociation. In both systems, H2 heterolysis is reversible, and the parent compound is recovered when exposed to vacuum.

|

2.2 |

|

2.3 |

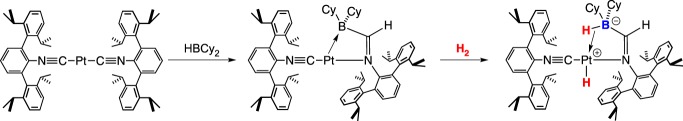

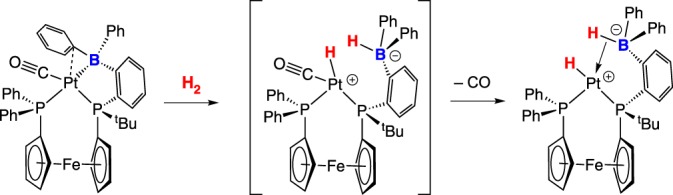

Figueroa and co-workers [20] reported a three coordinate platinum (boryl)iminomethane complex featuring a Pt–B bond that heterolytically cleaves H2 (scheme 4). This process is irreversible, possibly due to the unfavourable process of positioning the Pt–H close to the trans dative Pt–BH bond to regenerate H2. A Pt–B complex giving reversible H2 cleavage was reported by Cowie & Emslie [21]. The bis(phosphano)ferrocene-borane ligated platinum complex readily inserts H2 across the Pt–B bond upon treatment with H2 (scheme 5). In contrast with the Pt complex in scheme 4, the Pt–H in scheme 5 is cis to the dative Pt–BH bond. Exposure to argon or vacuum converts the platinum hydride back to the starting borane adduct. Treating the borane adduct with CO irreversibly forms a Pt–CO complex, whereby the arene–Pt bond is displaced. Surprisingly, CO can be displaced under an H2 atmosphere, generating the platinum hydride (scheme 5); the CO/H2 conversion reaction is reversible.

Scheme 4.

(Online version in colour.)

Scheme 5.

(Online version in colour.)

Mechanistically, M–B bond dissociation may not be required for heterolysis in scheme 5. The initial platinum–borane adduct is formally a platinum(0) compound, while the H2 cleavage product is a platinum(II) hydride. CO loss from low-valent platinum(0) is unlikely, which would suggest that H2 inserts into the Pt–B bond to generate a platinum(II) intermediate, whereafter CO loss would be more favourable (scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

(Online version in colour.)

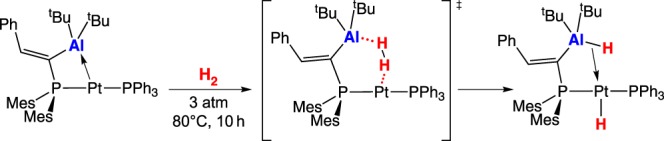

Bourissou and co-workers [22] reported a platinum–alumane adduct that heterolytically cleaves H2 (scheme 7). The heterolytic cleavage product is thermodynamically favoured over the weak Pt–Al bond, but elevated temperature and pressure are necessary to overcome the high-energy transition state, where the Pt twists away after heterolysis of H2 (scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

(Online version in colour.)

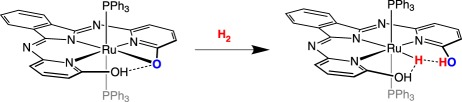

(c). Metal–oxygen and metal–sulfur complexes

Oxygen or sulfur can serve as the base in metal-containing FLP reactions. In a ruthenium complex reported by Geri & Szymczak [23], heterolytic cleavage of H2 occurs at a Ru–O bond, generating a ruthenium hydride and an aryl OH proton (equation (2.4)) with stabilization by hydrogen bonding. The proton and hydride in this system were found to be in rapid dynamic exchange [24]. No evidence that would suggest lability of the PPh3 ligands in the alkoxo complex was reported, which is consistent with H2 addition across the Ru–O bond without prior H2 coordination.

|

2.4 |

Heterolytic cleavage of H2 has also been reported for metal thiolate complexes. A practical consideration is that a monothiolato ligand serving as the proton recipient in H2 heterolysis produces a thiol, a substantially poorer donor that favours dissociation, as exemplified in work reported by Mizobe and co-workers [25]. Tp*Rh(SPh)2(MeCN) (Tp* = tris(3,5-dimethylpyrazolylborate)) reversibly cleaves H2, producing a rhodium hydride and free thiophenol (equation (2.5)). The 1,2-benzenedithiolate (bdt) derivative was unreactive in solution in the presence of H2, but addition of exogenous base gave the hydrido anion [Tp*Rh(bdt)H]−. The dithiolate complex is proposed to be in equilibrium with an H2 heterolysis product, whereafter exogenous base can deprotonate the thiol arm, re-enabling chelation of the thiolate (scheme 8).

|

2.5 |

Scheme 8.

(Online version in colour.)

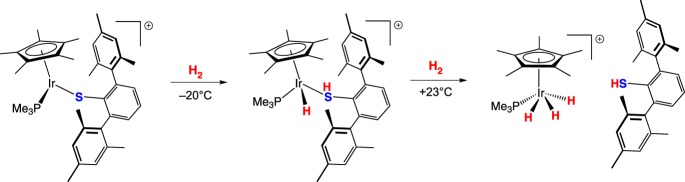

Though thiols are much weaker donors than their deprotonated form, ligand loss when a monothiolate acts as a proton acceptor is not assured. A thiolato iridium complex reported by Tatsumi and co-workers [26] heterolytically cleaves H2 at −20°C to generate an iridium hydrido thiophenol complex that was observed spectroscopically (scheme 9). Upon warming to +23°C under H2, the substituted thiophenol dissociates, and the iridium oxidatively adds H2 to give an iridium trihydride. DFT calculations suggest that H2 binds to the iridium centre prior to heterolytic cleavage [27].

Scheme 9.

(Online version in colour.)

The first reported example exhibiting heterolytic cleavage of H2 across a terminal metal sulfide occurred in Ti═S complex. Andersen and co-workers [28,29] found that Cp*2Ti(py)S cleaves H2 to yield the corresponding hydrido hydrosulfido complex Cp*2Ti(SH)H (scheme 10). NMR spectroscopic experiments supported the intermediacy of a dihydrogen complex, as shown in scheme 10. The H2 addition process is reversible, and NMR experiments show that the protons in the hydride, hydrosulfide and H2 are all in rapid exchange at room temperature in solution.

Scheme 10.

(Online version in colour.)

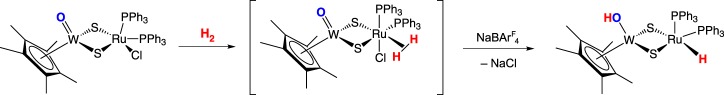

Tatsumi and co-workers have also reported heterobimetallic complexes that heterolytically cleave hydrogen. The RuS2W compound Cp*WO(μ-S)2Ru(PPh3)2Cl cleaves H2 in the presence of the halide abstractor NaBArF4 (ArF = 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl) (scheme 11); no reaction is observed with only H2 or only NaBArF4 [30]. The terminal oxo on tungsten is protonated, and the ruthenium receives the hydride. The mechanism for this process is not clear, and is complicated by the fact that the hydrogen atoms from H2 are trans in the product. The authors propose two possible pathways: an intermolecular pathway where the H2 adduct is deprotonated by the terminal oxo on a second molecule, and an intramolecular pathway in which H2 adds across the Ru–S bond and the resultant bridging hydrosulfide is intramolecularly deprotonated by the terminal oxo.

Scheme 11.

(Online version in colour.)

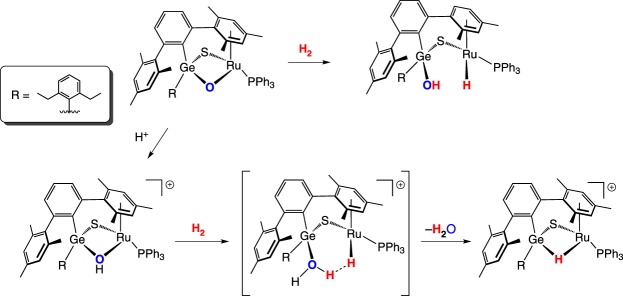

Another bimetallic sulfido complex reported by Tatsumi and co-workers that heterolytically cleaves H2 features a GeRu centre. Under 10 atm of H2, the chalcogenido-bridged GeRu complex (scheme 12) adds H2 across the Ru–O bond, giving a sulfido-bridged germanium hydroxo and ruthenium hydride [31]. Milder conditions can be used with the pre-protonated bridging hydroxo species, which is predicted by DFT computations to proceed through a hydrogen-bonded hydride intermediate where dihydrogen inserts into the Ru–O bond [32].

Scheme 12.

(Online version in colour.)

(d). An all-metal frustrated Lewis pair

The first example of a transition metal-only FLP that heterolytically cleaves H2 was recently reported by Campos using gold and platinum phosphane complexes [33]. Gold has a well-established use [34,35] in organic synthesis as a Lewis acid catalyst, and low-valent platinum is well known to function as a Lewis base, making this all-metal analogue reported by Campos germane to FLPs. The phosphano gold complex (ArDipp2MeP)Au(NTf2) (ArDipp2 = C6H3-2,6-(C6H3-2,6-iPr2)2) and the platinum phosphano complex Pt(PtBu3)2 are proposed to be in equilibrium with a metal–metal-bonded cation (scheme 13) on the basis of variable-temperature NMR spectroscopy; the monomers are highly favoured. Both the gold and platinum complexes are stable under H2 individually. Only when both complexes are present together is H2 heterolytically cleaved, producing a bimetallic dihydride.

Scheme 13.

(Online version in colour.)

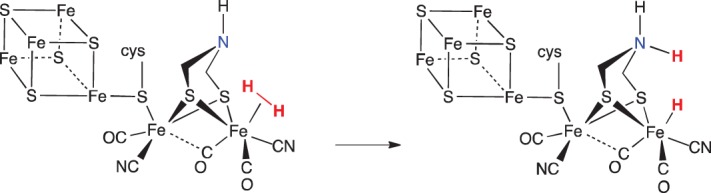

(e). Biologically inspired systems

(i). Models of [FeFe]-hydrogenase

The [FeFe]-hydrogenase (figure 2) reversibly and catalytically cleaves H2, and hydrogenases have been recognized as exhibiting FLP reactivity [36,37]. The remarkable identification of organometallic compounds in nature [38–40] spawned research by many groups worldwide to design and create structural and functional models of these enzymes that produce and oxidize hydrogen under ambient conditions, using only the Earth-abundant metals Fe and/or Ni [41–44]. In both the [FeFe]- and [NiFe]-hydrogenases, iron is believed to be the binding site for H2, whereafter it is heterolytically cleaved, transferring a hydride to the metal and a proton to a proximal base. The metal dihydrogen complex in these enzymes, while not directly observed, is poised between the metal and proximal base, analogous to H2 poised in a traditional main group FLP.

Figure 2.

Active site of [FeFe]-hydrogenase binding H2 and subsequent heterolytic cleavage assisted by a pendant amine. (Online version in colour.)

An early example of FLP reactivity was reported by Crabtree and co-workers [45]. The pendant amine of a cyclometallated iridium benzoquinolate complex does not coordinate to the iridium centre due to the strain of the metallacyclobutane that would result (equation (2.6)). The amine in this FLP assists in the heterolytic cleavage of H2. The unfunctionalized benzoquinolate derivative was similarly prepared; without the pendant amine, a stable iridium dihydrogen complex is generated upon exposure to H2

|

2.6 |

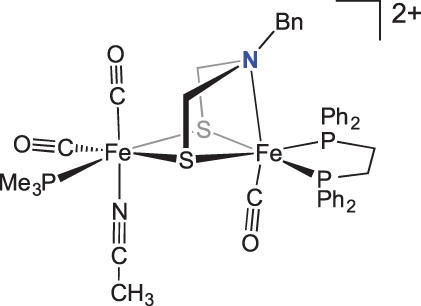

Recent work has focused on structural models with similarity to the [FeFe]-hydrogenase active site. Rauchfuss and co-workers reported [FeFe]-hydrogenase model compounds incorporating the azadithiolate motif [46,47]. Pendant amine positioning and flexibility are crucial to the successful design of synthetic systems exhibiting reactivity with H2. In the absence of metal–metal bonding and a third bridging ligand, the pendant amine is free to bind to an iron centre in the oxidized forms of the model compounds (figure 3).

Figure 3.

[FeFe]-hydrogenase model compound where the pendant amine binds to the metal centre. (Online version in colour.)

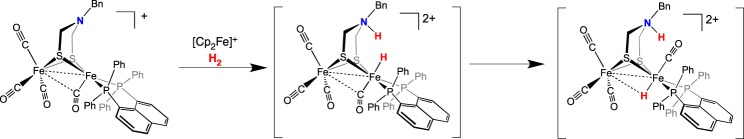

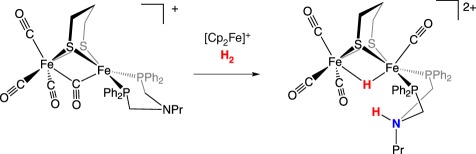

When metal–metal bonding or a third bridging interaction is maintained, leading to the iron centres being further from the pendant amine, in conjunction with a sterically cumbersome phosphane, the pendant amine is unable to access the iron vacant site (scheme 14). This FLP heterolytically cleaves H2, but only in the presence of an external oxidant. This observation implies the presence of an unfavourable equilibrium of the cation and an H2 complex whereby the H2 adduct is readily oxidized. The increased acidity of the metal dihydrogen complex following oxidation makes deprotonation by the pendant amine favourable.

Scheme 14.

(Online version in colour.)

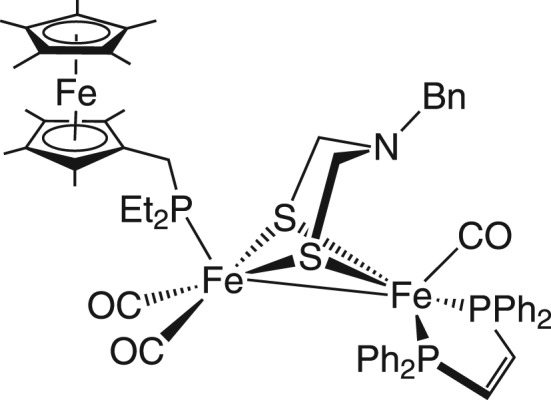

In an effort to accommodate the need for an oxidant following H2 binding, Camara & Rauchfuss [48] reported a model bearing an appended ferrocene to serve as an internal redox shuttle, mimicking the behaviour of the Fe4S4 clusters of the enzyme (figure 4). This triiron system is a functional model and catalyses H2 oxidation in the presence of exogenous base and oxidant.

Figure 4.

Structural model of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase active site bearing a pendant amine and redox reservoir.

Though the heterolytic cleavage of H2 in the native hydrogenase enzyme is facilitated by a pendant base within the dithiolate linker, a synthetic model that incorporates the internal base within a diphosphane ligand was reported by Sun and co-workers [49]. They found that their complex is a catalyst for oxidation of H2 using a chemical oxidant and a phosphane as the base. The bioinspired catalyst [(CO)3Fe(pdt)Fe(PPhNPrPPh)(CO)]+ (pdt = 1,3-propanedithiolate, PPhNPrPPh = (Ph2PCH2)NPr) differs from the natural system, in that H2 oxidation catalysis is believed to proceed through a bridging hydride species (equation (2.7)). The bridging position is typically the most thermodynamically favourable protonation site, but the strict conformational enforcement from the peptide backbone in the native enzyme prevents isomerization of hydride species and restricts access to this position. Catalytic activity in model compounds that use the biomimetic azadithiolate motif are generally inactivated or inhibited when protonation or isomerization generates bridging hydride species, where the pendant amine can no longer access the proton [50].

|

2.7 |

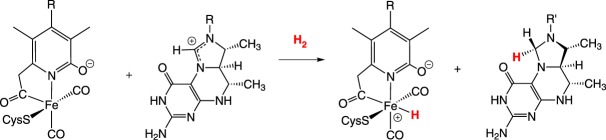

(ii). Models of [Fe]-hydrogenase

The reactivity of the mono iron hydrogenase [51] differs from the [NiFe]- and [FeFe]-enzymes: the catalysed reaction is not the interconversion of H2 into 2H+ and 2e−; instead the [Fe]-hydrogenase catalyses the hydrogenation and dehydrogenation of the substrate methylene-H4MPT (equation (2.8)).

|

2.8 |

Less is known about this hydrogenase compared with the other types; evidence suggests that H2 heterolysis does not proceed in the absence of substrate [52], suggesting the possibility of a traditional FLP-type interaction.

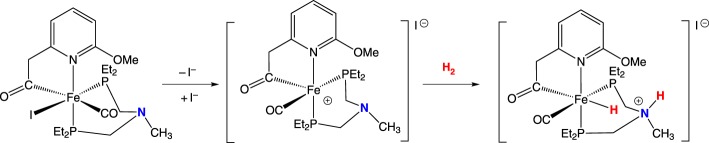

Although the mono-Fe hydrogenase does not possess a base, Hu and co-workers [53] have reported a bioinspired functional model of [Fe]-hydrogenase that functions similarly to traditional main group FLPs. The iron complex rapidly produces HD under an H2/D2 atmosphere in solution. This process is proposed to be facilitated by an FLP in which iodide dissociates, opening a vacant site on iron for H2 binding and subsequent H2 cleavage (scheme 15). In this model complex, iron functions as a hydride acceptor, compared with the protonation of the metal shown in equation (2.7), where the hydride acceptor is the carbon of methylene-H4MPT.

Scheme 15.

(Online version in colour.)

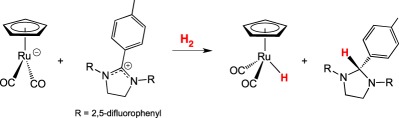

Meyer and co-workers [54] modelled the reactivity of the [Fe]-hydrogenase in an intermolecular approach that uses [CpRu(CO)2]− anion as the proton acceptor and an imidazolium cation that is structurally similar to the methenyl-HMPT+ as the hydride acceptor (equation (2.9)). Using DFT analysis, heterolytic cleavage in this a Ru/imidazolium system is proposed to occur through an encounter complex, a commonly proposed mechanism in main group FLPs.

|

2.9 |

(iii). Models of [NiFe]-hydrogenase

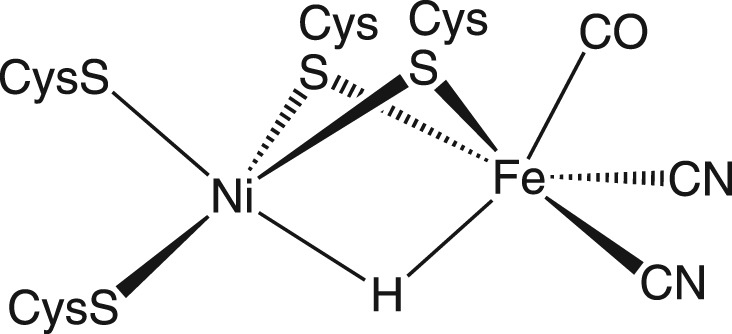

In addition to the different metals involved, a key difference between [NiFe]- and [FeFe]-hydrogenase is that the base involved in catalytic turnovers in the [NiFe]-system is usually proposed to be a terminally bound cysteinate at nickel (figure 5) as opposed to a pendant base in the [FeFe]-hydrogenase [41–44]. Work by Armstrong and co-workers [37] suggests that a basic residue in close proximity to the bimetallic active site of the [NiFe]-hydrogenase could serve as a base for H2 heterolysis, which would more closely resemble the proposed mechanism for the [FeFe]-H2 hydrogenase.

Figure 5.

Active site of the [NiFe]-hydrogenase.

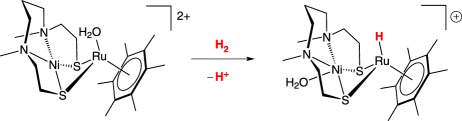

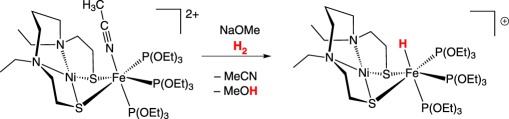

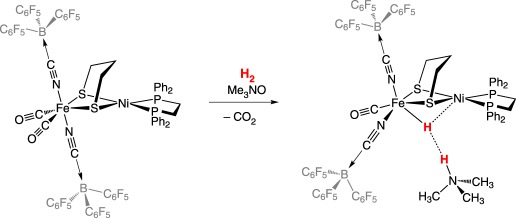

Models of the [NiFe]-hydrogenase that heterolytically cleave H2 and use the native metals are rare, and known examples use exogenous base to heterolytically cleave H2. The first [NiFe]-hydrogenase heterobimetallic model incorporating nickel that heterolytically cleaved H2 was reported by Ogo and co-workers (equation (2.10)) [55]. Using a similar amino-thiolate scaffold, Ogo and co-workers [56] later reported a catalytically competent model using iron instead of the precious metal ruthenium (equation (2.11)). Catalytically active models of either hydrogenase that incorporate cyanide are rare because of the Lewis basicity of the cyanide ligand, leading to oligomerization or protonation. Manor & Rauchfuss [57] reported a catalytically active [NiFe]-hydrogenase model compound that mimics both the bridging thiolate linkers and the diatomic donors, carbon monoxide and cyanide at iron. The dicarbonyl dicyano iron centre in the starting material is coordinatively saturated; trimethylamine N-oxide is used as a decarbonylating agent and, in the presence of H2, subsequently serves as the exogenous base for H2 heterolysis (equation (2.12)).

|

2.10 |

|

2.11 |

|

2.12 |

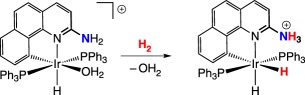

3. Catalytic systems

(a). Frustrated Lewis pair reactivity in the catalytic hydrogenation of ketones

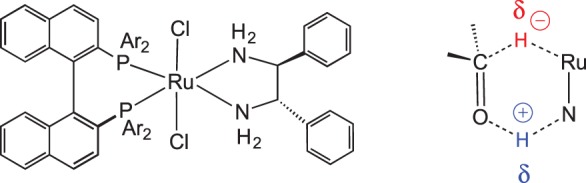

Bifunctional catalysis has become a powerful method for synthesis of chiral alcohols and is an additional case of transition metal-mediated H2 heterolysis. Noyori and co-workers [58–61] developed chiral Ru catalysts that are extremely fast for asymmetric hydrogenations of ketones. The Ru complex with chiral diphosphanes that is a catalyst precursor is shown in figure 6; Ru catalysts were also developed for transfer hydrogenation from alcohols. Along with the high reactivity of these catalysts, they are also important because of the metal–ligand bifunctional mechanism [62]. In contrast with traditional catalysts for ketone hydrogenation, coordination of the ketone to the metal is not required in the metal–ligand bifunctional mechanism. Computations suggested a pericyclic transition state, as sketched in figure 6, involving concerted proton transfer from the N–H bond to the oxygen of the ketone, and hydride transfer from the Ru–H to the carbon of the ketone.

Figure 6.

Noyori's chiral hydrogenation catalyst precursor, and proposed pericyclic transition state. (Online version in colour.)

Initial DFT calculations suggested that the reaction proceeds through a concerted pathway, but more recent computations by Dub & Ikariya [63], incorporating the influence of explicit solvent molecules, led to an interpretation that the hydrogenation proceeds by hydride transfer followed by proton transfer. Morris and co-workers developed highly reactive Fe catalysts for asymmetric ketone hydrogenation [64,65], and computations on some of those Fe catalysts also indicate hydride transfer preceding proton transfer [66]. Studies by Poli and co-workers [67] on Ir complexes provides another example for stepwise hydride transfer before proton transfer.

Dub & Gordon [68–70] reported extensive computational studies on these Ru complexes, leading to new interpretations on the role of hydrogen bonding and revealing details of the mechanism of heterolytic cleavage of H2. Their computations suggest that the heterolytic cleavage of H2 leading to the formation of the Ru–H and N–H bonds is strongly influenced by hydrogen bonding involving deprotonation of the Ru(H2) complex by an alkoxide.

Many of the highly active Fe catalysts developed by Morris and co-workers function by transfer hydrogenation, with isopropyl alcohol serving as the source of H2, but some of their Fe catalysts use H2. One example that was studied in detail by kinetics and computational studies is shown in scheme 16, where heterolytic cleavage of H2 occurs [71].

Scheme 16.

(Online version in colour.)

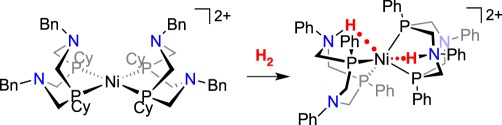

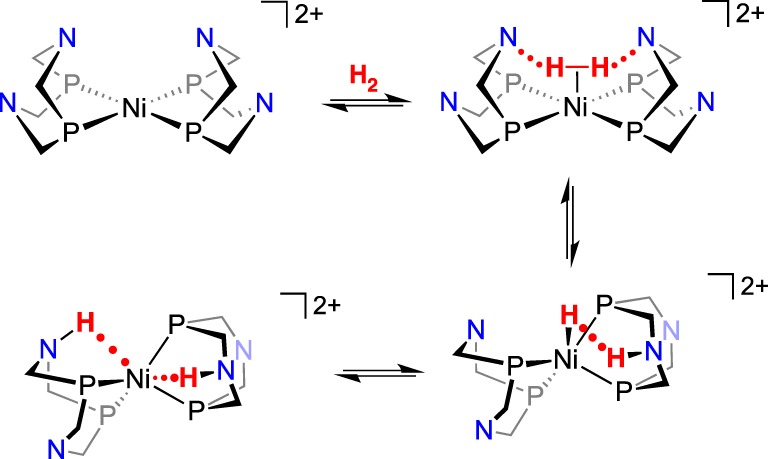

(b). Frustrated Lewis pair reactivity in Ni(P2N2) complexes

DuBois and co-workers prepared Ni(II) complexes bearing two ‘PNP’ ligands (PNP = (R2PCH2)2NR’) bearing amines in the diphosphane ligand (equation (3.1)) [72]. Addition of H2 gives heterolytic cleavage of H2, showing that this complex has metal-based FLP reactivity, with the formation of a nickel hydride and protonation of one amine, a reaction modelling the function of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase. The 1H NMR spectrum of the product of heterolytic cleavage showed one resonance at room temperature for the NiH and the NH, but two distinct resonances at low temperature. A rate of about 104 s−1 was estimated at 25°C for the intramolecular exchange of proton and hydride, which could proceed through an unobserved NiII(H2) complex or a NiIV dihydride. This Ni complex is an electrocatalyst for oxidation of H2 when NEt3 is added to the solution, serving as an exogenous base.

|

3.1 |

It was recognized that the slow rate of electrocatalytic oxidation of H2 by the Ni(PNP)22+ complexes might be caused by slow reaction with H2. To carry out the FLP reaction and heterolytically cleave H2, Ni(PNP)22+ must adopt a geometry that places the hydride acceptor (the metal) and the proton acceptor (the pendant amine) in a suitable geometry to interact with H2. The six-membered chelating ring containing the metal and the diphosphane can adopt a chair or boat conformation, but it is properly oriented to react with H2 only when it is in the boat conformation. By contrast, Ni(P2N2)22+ complexes, one example of which is shown in equation (3.2), typically have at least one of the amines in the boat conformation, greatly increasing the probability that a binding site is poised to bind and heterolytically cleave H2. Variable-temperature NMR experiments established the rates of chair–boat interconversion for several of these Ni(II) complexes [73]. Electrocatalytic oxidation of H2 by [Ni(PCy2NBn2)2]2+ gave turnover frequencies (ToFs) of about 10 s−1 [74]. Studies of related Ni complexes for the opposite reaction, production of H2 by reduction of protons, have led to TOFs as high as 107 s−1 [75,76]. The catalytic activity of these complexes has been discussed recently [77] and is not the main focus of this perspective.

|

3.2 |

Traditional reactions of H2 with metal complexes lead to oxidative addition to give a dihydride, often through the intermediacy of a dihydrogen complex. The heterolytic cleavage of H2 is a different type of reaction, leading to a metal hydride and the proton on a ligand, such as an N–H bond. The reaction shown in equation (3.2) deviates from the typical reactivity, because both protons originating from H2 are on nitrogens, and the two electrons from H2 have reduced the NiII complex to Ni0. Although the product has the two N–H protons in equivalent positions, computational analysis [78] of the reaction provides evidence for a pathway that features heterolytic cleavage of H2 as the key step exhibiting FLP reactivity. The identification of the doubly protonated product raises a question of whether this reaction is pertinent to the topic of this perspective: Does this reaction involve heterolytic cleavage of H2?

As illustrated in scheme 17 (cyclohexyl groups on P and tert-butyl groups on N are not shown), the initial interaction of H2 with [Ni(P2N2)2]2+ is proposed to give a dihydrogen complex that is not observed experimentally. Note that, in the isomer shown, the two nitrogens that are interacting with the H2 are in the boat conformation, whereas the other two rings are in a chair conformation. Even when the reaction of [Ni(PCy2Nt-Bu2)2]2+ with H2 was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy at −100°C, no evidence for the intermediacy of [Ni(H2)(PCy2Nt-Bu2)2]2+ was obtained; the kinetically favoured doubly protonated Ni0 product was observed [79]. Computations on [Ni(PCy2NMe2)2]2+ indicate that the binding of H2 is uphill in free energy by about 9 kcal mol−1, with most of that being caused by the translational energy lost by the free H2 as it binds to the complex [78]. The thermodynamically unfavourable binding of H2 to this NiII complex contrasts with the stronger binding of H2 to many other metals, leading to stable M(H2) complexes [80–82]. The FLP reactivity occurs promptly after binding of H2, with the heterolytic cleavage delivering a hydride to Ni and a proton to the pendant amine. This complex is not observed in the [Ni(P2N2)2]2+ complexes, but converts to the doubly protonated Ni(0) complex, as shown in scheme 17. In contrast with the facile heterolytic cleavage of H2, homolytic cleavage of H2 in this system, which would produce a NiIV dihydride complex, was computed to have a much higher barrier than heterolytic cleavage [78].

Scheme 17.

(Online version in colour.)

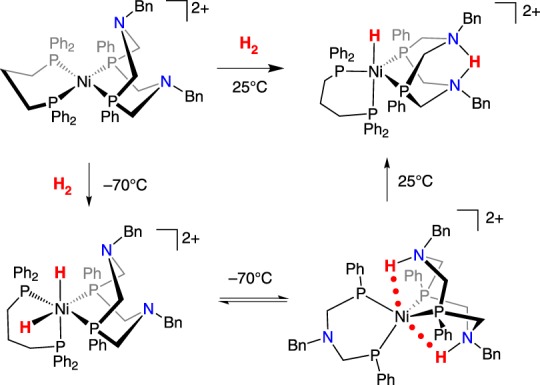

A NiII with just one P2N2 ligand, [Ni(dppp)(PCy2NBn2)]2+ (dppp = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphano)propane)), reacts with H2 at 25°C to generate the complex shown in scheme 18, with a Ni–H and the proton ‘pinched’ between two amines of the protonated P2N2 ligand [83]. The product clearly indicates that FLP reactivity has occurred, and low-temperature NMR spectroscopy experiments gave further insight into the reaction. When the reaction with H2 was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy at −70°C, two complexes were observed, as shown in scheme 18. A rare NiIV dihydride complex was assigned on the basis of a resonance at −8.8 ppm, along with experiments using HD and D2. The dihydride complex was found to be in equilibrium with a Ni0 complex that had two N–H bonds (scheme 18). When the solution was warmed to higher temperatures, the conversion to the NiH/NH product was observed. Electrocatalytic oxidation of H2 (1 atm) was catalysed by [Ni(dppp)(PCy2NBn2)]2+, with a TOF of about 0.4 s−1 [83].

Scheme 18.

(Online version in colour.)

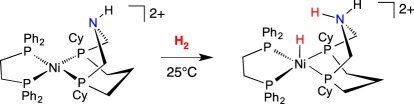

In comparison to extensive studies of Ni complexes bearing PR2NR′2 ligands, with two amines in the cyclic ligand, recent studies were conducted on related complexes where only the diphosphane bears just one amine substituent. FLP reactivity was observed when treated with H2, as shown in equation (3.3), giving heterolytic cleavage of H2 and formation of a NiH/NH complex [84].

|

3.3 |

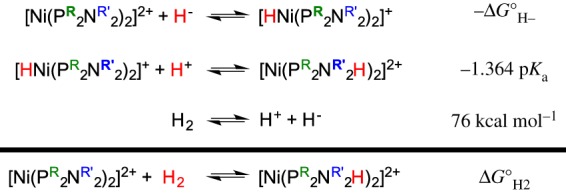

For main group FLP systems, heterolytic cleavage of H2 can apparently occur without binding of H2. Determination of the thermodynamics of the H2 addition/cleavage reaction can guide prediction of the reactivity of metal FLP systems. For the Ni complexes discussed above, extensive studies have provided an understanding of the factors that influence the free energy for heterolytic cleavage of H2. The thermochemical cycle shown in figure 7 shows how the free energy for addition of H2 to [Ni(P2N2)2]2+ complexes can be experimentally determined. The first equation is the hydride acceptor ability for the NiII complex to produce [HNi(P2N2)2]+. While written as a hydride acceptor reaction, this reaction is often considered in the opposite direction, the hydride donor ability (hydricity) of a metal hydride [85]. The thermodynamics of hydride transfer reactions of metal hydrides have been determined for many metal hydrides and can be measured by several methods, as discussed in a recent review [85]. The second reaction is the pKa of the N–H bond, which can be measured by relative pKa measurements compared with a series of acids of known pKa values [86,87]. The third component of the thermochemical cycle is the free energy for heterolytic cleavage of H2, which is 76 kcal mol−1 in MeCN [88]. The value of the free energy for heterolytic cleavage of H2 depends substantially on the solvent; for example, it is 34.2 kcal mol−1 in water [89].

Figure 7.

Thermodynamic cycle for determination of the free energy of H2 addition to [Ni(P2N2)2]2+ complexes. (Online version in colour.)

Changes to the ligands on these Ni complexes will thus impact the hydride acceptor ability of the metal, as well as the basicity of the amine. To design a metal complex that will heterolytically cleave H2, different combinations of hydride acceptor ability and basicity could provide thermodynamically favourable systems. For example, the free energy for H2 addition is ΔG°H2 = −7.9 kcal mol−1 [79] for the derivative with sterically encumbering cyclohexyl groups on the phosphane and tert-butyls on the amines, [Ni(PCy2Nt-Bu2)2]2+. As binding of H2 is required in molecular electrocatalysts for oxidation of H2, ΔG°H2 < 0 is needed. By contrast, electrocatalysts for the opposite reaction, production of H2 by reduction of protons, should not bind H2 but should evolve H2 instead [90]. The H2 production electrocatalyst [91] [Ni(PPh2NPh2)2]2+, with Ph groups on the phosphanes and amines, has ΔG°H2 = +8.8 kcal mol−1 [92]. By altering the basicity of the pendant amine and the hydride acceptor ability of the nickel centre, the free energy for H2 addition to [Ni(P2N2)2]2+ complexes can be varied by 22 kcal mol−1 [77]. These same principles have been applied more broadly to the design of metal-based FLPs for heterolytic cleavage of H2, as discussed below.

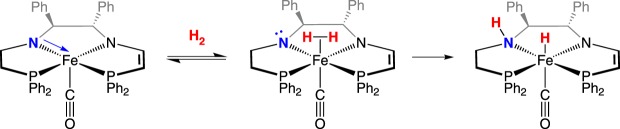

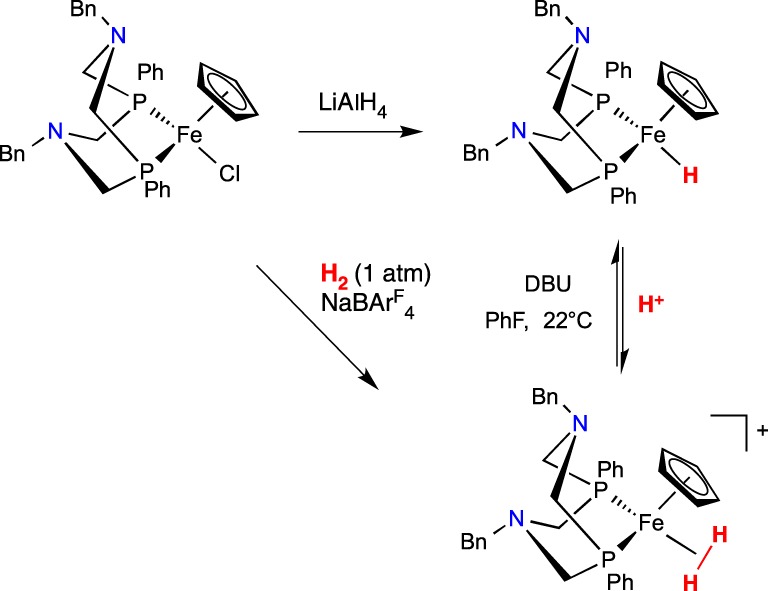

(c). Fe(P2N2) and Fe(PNP) complexes

We sought to achieve FLP reactivity in Fe complexes by installing P2N2 ligands onto CpFe complexes, as in scheme 19. When CpFe(PPh2NBn2)Cl was stirred under H2 with NaBArF4, the cationic dihydrogen complex [CpFe(PPh2NBn2)(H2)]+ was generated [93]. The same complex was prepared by protonation of the iron hydride (scheme 19). The stability of the dihydrogen shows that this system is not capable of intramolecular heterolytic cleavage of H2. These complexes carried out the individual steps needed to function as electrocatalysts for oxidation of H2, but they failed as catalysts. Under the conditions needed for catalysis, an organic amine base is added, and the amine appeared to bind to the Fe, precluding binding of H2, and hence preventing catalysis.

Scheme 19.

(Online version in colour.)

A related complex with tert-butyl groups on the phosphane was prepared to provide more steric bulk near the metal [94]. The tert-butyl groups on the phosphane make the iron more electron-rich, and its hydride and dihydrogen complexes less acidic. An electron-withdrawing perfluorophenyl (C6F5) group was installed on the Cp ligand to counterbalance the electronic changes.

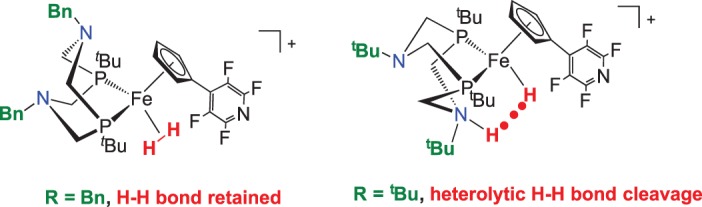

Modification of the basicity of the pendant amine led to the ability to control the energy for heterolytic cleavage [95]. Sterically bulky substituents to block exogenous base was only one part of the solution to ineffective catalysis in the Cp derivative in scheme 19; the acidity of the Fe–H2 complex must be high enough for deprotonation. Changing the organic group on the amine from benzyl to tert-butyl alters the free energy for heterolytic cleavage, favouring it more than for the complex with benzyl groups. Consequently, the H–H bond is heterolytically cleaved (figure 8).

Figure 8.

Amine substituent influence on thermodynamic favourability of H2 cleavage. (Online version in colour.)

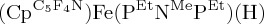

The structure of  was determined by single-crystal neutron diffraction [96], providing a precise determination of the positions of the hydrogen atoms. The H···H separation of 1.489(10)Å suggests strong ‘dihydrogen bonding’ [97–99], between the protic NHδ+ and the hydridic FeHδ−. This H···H separation is much larger than the H–H distance found in dihydrogen complexes. For example, an H–H distance of about 0.94Å was estimated for the dihydrogen ligand of

was determined by single-crystal neutron diffraction [96], providing a precise determination of the positions of the hydrogen atoms. The H···H separation of 1.489(10)Å suggests strong ‘dihydrogen bonding’ [97–99], between the protic NHδ+ and the hydridic FeHδ−. This H···H separation is much larger than the H–H distance found in dihydrogen complexes. For example, an H–H distance of about 0.94Å was estimated for the dihydrogen ligand of  on the basis of the J(HD) coupling constant in the 1H NMR spectrum of the HD complex [94]; a series of related Fe(H2) complexes have also been compared using NMR spectroscopic measurements [95]. This study of heterolytic cleavage by an iron complex with a pendant amine provides a model for the heterolytic cleavage of H2 in the more complex [FeFe]-hydrogenase in nature, where obtaining reliable structural data of enzymes is often difficult.

on the basis of the J(HD) coupling constant in the 1H NMR spectrum of the HD complex [94]; a series of related Fe(H2) complexes have also been compared using NMR spectroscopic measurements [95]. This study of heterolytic cleavage by an iron complex with a pendant amine provides a model for the heterolytic cleavage of H2 in the more complex [FeFe]-hydrogenase in nature, where obtaining reliable structural data of enzymes is often difficult.

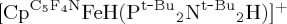

Following the development of these Fe catalysts using P2N2 ligands, studies on related  complexes (PEtNMePEt = (Et2PCH2)2NMe) led to faster electrocatalytic oxidation of H2 (8.6 s−1), though at a higher overpotential [100]. A significant barrier in the catalytic reaction arises from the thermodynamically unfavourable proton transfer from the oxidized FeIII hydride to the pendant amine. Incorporation of an additional pendant amine in the outer coordination sphere, as shown in scheme 20, leads to much faster catalysis, with a TOF of 290 s−1 [101].

complexes (PEtNMePEt = (Et2PCH2)2NMe) led to faster electrocatalytic oxidation of H2 (8.6 s−1), though at a higher overpotential [100]. A significant barrier in the catalytic reaction arises from the thermodynamically unfavourable proton transfer from the oxidized FeIII hydride to the pendant amine. Incorporation of an additional pendant amine in the outer coordination sphere, as shown in scheme 20, leads to much faster catalysis, with a TOF of 290 s−1 [101].

Scheme 20.

(Online version in colour.)

When the heterolytic cleavage of H2 occurs in this Fe-based catalyst, the pendant amine in the outer coordination sphere stabilizes the N–H bond in the second coordination sphere by forming an intramolecular N–H···N hydrogen bond. This hydrogen bond reduces the difference in acidity between the iron hydride and the pendant amine. In the proposed mechanism, the proton is relayed from the metal to the pendant amine to the second pendant amine in the outer coordination sphere, and finally to the exogenous base in solution, which is related to proton transfer pathways in hydrogenases, where protons are shuttled through amino acids in the enzyme.

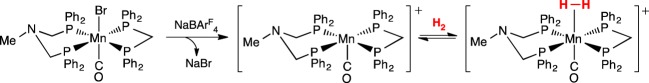

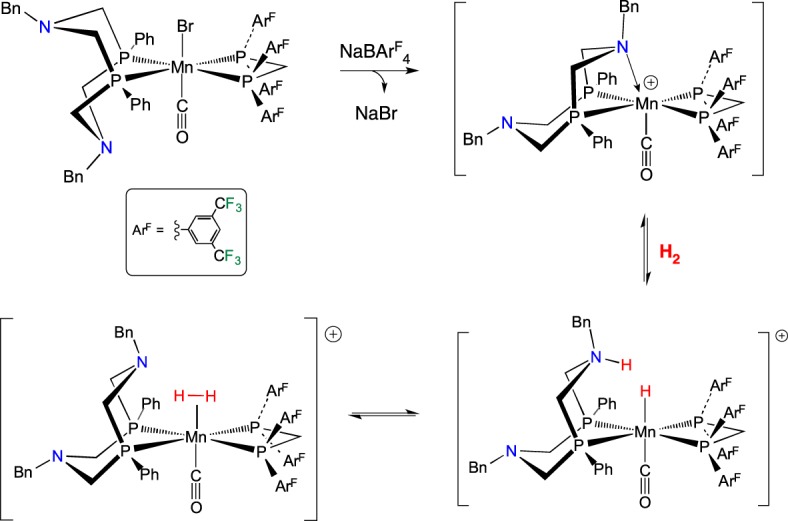

(d). Mn amino-phosphane complexes

Dihydrogen complexes of Mn, such as [Mn(H2)(dppe)2(CO)]+, were reported by Kubas and co-workers [102,103]. Recognizing the heterolytic cleavage of H2 that had been achieved in the Ni and Fe complexes discussed above, using pendant amines in the diphosphane ligands, we prepared Mn complexes bearing the PNP ligand, PPhNMePPh, as shown in scheme 21. Conversion of the Mn bromide complex to a cationic Mn complex, followed by addition of H2, led to the observation of Mn dihydrogen complexes [104]. The binding of H2 was reversible, with Keq = 26 atm−1 in PhF for the Mn(H2)+ complex shown in scheme 21. The failure to observe FLP reactivity in this Mn complex was attributed to a thermodynamic problem: the H2 ligand was not sufficiently acidic, or, stated in an equivalent way, the pendant amine was not basic enough to deprotonate the H2 ligand. Changing to a diphosphane ligand bearing electron-withdrawing groups should lead to a metal complex that is less electron-rich, so its dihydrogen ligand should be more acidic.

Scheme 21.

(Online version in colour.)

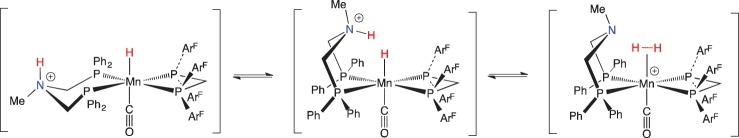

In accordance with this reasoning, we synthesized Mn complexes bearing a bppm ligand (bppm = (PArF2)2CH2), which has CF3 groups on the meta positions of the aryl ring (scheme 22) [105]. Removal of bromide from MnBr(PPh2NBn2)(bppm)(CO) gave a cationic Mn complex with a κ3-PPh2NBn2 ligand, in which one of the pendant amines bonds to the Mn [106]. This Mn–N complex is a Lewis acid–base adduct, yet it exhibits FLP reactivity. Upon addition of H2, the weak Mn–N bond is displaced, and heterolytic cleavage of H2 occurs, placing the hydride on Mn and a proton on the amine. Crystals of the MnH/NH complex were grown under an H2 atmosphere, and the structure was verified by X-ray crystallography. The 1H NMR spectrum of this complex does not exhibit the expected resonances for the MnH (expected around −5 ppm) or for the NH of a protonated amine (typically 7–11 ppm). Instead, an averaged resonance was observed at 2.55 ppm that integrated to 2H. Extensive spectroscopic studies, including multi-nuclear 2D NMR spectroscopy, D2 and HD labelling, provided evidence for reversible heterolytic cleavage of H2, as shown in scheme 22. A lower limit of the rate of reversible heterolytic cleavage was estimated as 1.5 × 104 s−1 at −95°C [105]. It was estimated that the rate at 25°C could be greater than 107 s−1.

Scheme 22.

(Online version in colour.)

For the complex in scheme 22, the Mn–N FLP only exists when the PNP ligand is in the boat conformation. Because the six-membered ring in the PNP ligand system is free to undergo chair–boat isomerization, the rate of reversible heterolytic H2 cleavage found for the Mn complex shown in scheme 23 is much slower than that discussed above for the analogous complexes with P2N2 ligands. A proton–hydride exchange rate of 9.7 × 103 s−1 at 20°C was determined, which is several orders of magnitude slower than that found for the Mn–P2N2 complexes [106]. These Mn complexes are electrocatalysts for oxidation of H2 in PhF solution, with a TOF of 3.5 s−1 found for [(PPh2NBn2)MnI(CO)(bppm)]+ [107].

Scheme 23.

(Online version in colour.)

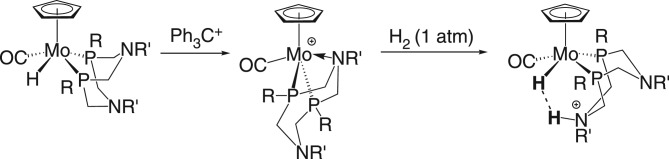

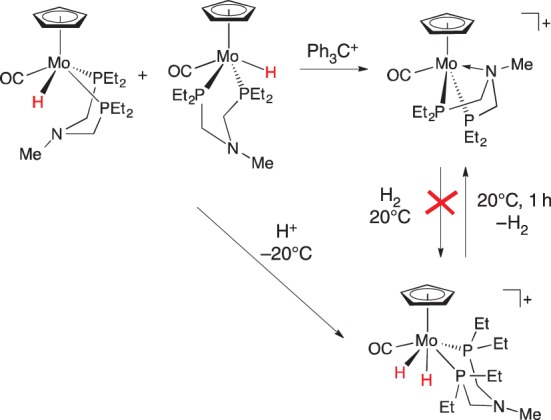

(e). Mo amino-phosphane complexes

Molybdenum and tungsten complexes [Cp(CO)2(PR3)M(H)2]+ are catalysts for the ionic hydrogenation of ketones [108–110]. The catalysis proceeds under mild conditions (1 atm H2) but is slow; studies on these complexes provided insight into the elementary steps of the mechanism, which was proposed to involve proton transfer from a cationic dihydride complex and hydride transfer from the neutral metal hydride. Incorporating a pendant amine on the diphosphane provides the possibility of separating the Lewis acid and base, and hence of obtaining FLP reactivity.

The molybdenum hydride complex CpMo(CO)(PEtNMePEt)H is a mixture of cis and trans isomers (scheme 24), and hydride abstraction using Ph3C+ gives the complex [CpMo(CO)(κ3-PEtNMePEt)]+ [111]. This complex, with a Mo–N bond, does not exhibit FLP reactivity. No reaction with H2 was observed, indicating that its potential FLP reactivity is quenched by the Mo–N bond. The cationic dihydride [CpMo(CO)(PEtNMePEt)(H)2]+ was prepared by protonation of the neutral metal hydride; in solution at 20°C, H2 is lost from the dihydride, generating [CpMo(CO)(κ3-PEtNMePEt)]+.

Scheme 24.

(Online version in colour.)

Changing from PNP ligands to P2N2 ligands on molybdenum led to different reactivity [112]. Similar to the PNP complexes shown in scheme 24, the amine binds to Mo in [CpMo(CO)(κ3-P2N2)]+. The crystal structure of [CpMo(CO)(κ3-Pt-Bu2NBn2)]+ and two related complexes showed longer Mo–N bond lengths compared with the Mo–N bond distance in [CpMo(CO)(κ3-PEtNMePEt)]+, suggesting a weaker Mo–N bond in the [CpMo(CO)(κ3-P2N2)]+ complexes. The P–M–P bond angles in PNP and P2N2 complexes are markedly different, the latter typically having tighter bite angles. The consequence of this structural feature is greater strain induced within the metallocyclic ring in κ3-P2N2 complexes compared with κ3-PNP [111]. Addition of H2 (1 atm) to the [CpMo(CO)(κ3-P2N2)]+ complexes led to rapid heterolytic cleavage of H2 at room temperature (scheme 25).

Scheme 25.

Variable-temperature NMR spectroscopic studies provided the rates of hydride–proton exchange for five [CpMo(CO)(κ3-P2N2)]+ complexes, which is thought to occur by reversible formation of the H–H bond, as shown in scheme 25. The rates at 25°C spread over a range of about 104, from 2.0 × 103 s−1 measured for [CpMo(CO)(Pt-Bu2Nt-Bu2H)H]+ to an estimated value of 4.0 × 107 s−1 for [CpMo(CO)(PPh2NPh2H)H]+. Deprotonation of these [CpMo(CO)(PR2NR2H)H]+ complexes gave the corresponding CpMo(CO)(P2N2)H metal hydride complexes. The pKa values were measured for deprotonation of these [CpMo(CO)(PR2NR2H)H]+ complexes in MeCN solution, ranging from 9.3 for [CpMo(CO)(PPh2NPh2H)H]+ to 17.7 for [CpMo(CO)(Pt-Bu2Nt-Bu2H)H]+. The pKa values are linearly correlated with the logarithm of the exchange rates, providing a rare example of systematically controlling the rate of heterolytic cleavage of H2 in a metal-based FLP system.

4. Concluding remarks

The nomenclature of FLPs, first articulated for main group reactivity, has parallels in many reactions of transition metal complexes. Heterolytic cleavage of H2 is accomplished by several types of metal complexes, and is especially prevalent in reactions in which a hydride is delivered to a metal, and the proton is delivered to an amine incorporated into the ligand. Some examples are relevant to the biological reactions of hydrogenase, where heterolytic cleavage in these enzymes occurs under mild conditions. Recent progress has identified some of the key factors that control the rates of heterolytic cleavage of H2 in synthetic complexes, leading to catalytic reactions that are important in organic synthesis and energy conversion reactions.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed substantially to the writing and revision of this article.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported as part of the Center for Molecular Electrocatalysis, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is operated by Battelle for the US DOE.

References

- 1.Welch GC, Juan RRS, Masuda JD, Stephan DW. 2006. Reversible, metal-free hydrogen activation. Science 314, 1124–1126. ( 10.1126/science.1134230) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn SR, Wass DF. 2013. Transition metal frustrated Lewis pairs. ACS Catal. 3, 2574–2581. ( 10.1021/cs400754w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grützmacher H. 2008. Cooperating ligands in catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 1814–1818. ( 10.1002/anie.200704654) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunanathan C, Milstein D. 2011. Metal–ligand cooperation by aromatization–dearomatization: a new paradigm in bond activation and green catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 588–602. ( 10.1021/ar2000265) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khusnutdinova JR, Milstein D. 2015. Metal–ligand cooperation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 12 236–12 273. ( 10.1002/anie.201503873) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rokob TA, Bakó I, Stirling A, Hamza A, Pápai I. 2013. Reactivity models of hydrogen activation by frustrated Lewis pairs: synergistic electron transfers or polarization by electric field? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 4425–4437. ( 10.1021/ja312387q) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimme S, Kruse H, Goerigk L, Erker G. 2010. The mechanism of dihydrogen activation by frustrated Lewis pairs revisited. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 1402–1405. ( 10.1002/anie.200905484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Lukose B, Ensing B. 2017. Hydrogen activation by frustrated Lewis pairs revisited by metadynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 2046–2051. ( 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b09991) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris RH. 2016. Brønsted–Lowry acid strength of metal hydride and dihydrogen complexes. Chem. Rev. 116, 8588–8654. ( 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00695) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman AM, Haddow MF, Wass DF. 2011. Frustrated Lewis pairs beyond the main group: synthesis, reactivity, and small molecule activation with cationic zirconocene–phosphinoaryloxide complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18 463–18 478. ( 10.1021/ja207936p) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jian Z, Daniliuc CG, Kehr G, Erker G. 2017. Frustrated Lewis pair vs metal–carbon σ-bond insertion chemistry at an o-phenylene-bridged Cp2Zr+/PPh2 system. Organometallics 36, 424–434. ( 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00828) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hounjet LJ, Bannwarth C, Garon CN, Caputo CB, Grimme S, Stephan DW. 2013. Combinations of ethers and B(C6F5)3 function as hydrogenation catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 7492–7495. ( 10.1002/anie.201303166) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosorius C, Kehr G, Fröhlich R, Grimme S, Erker G. 2011. Electronic control of frustrated Lewis pair behavior: chemistry of a geminal alkylidene-bridged per-pentafluorophenylated P/B pair. Organometallics 30, 4211–4219. ( 10.1021/om200569k) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stute A, Kehr G, Daniliuc CG, Frohlich R, Erker G. 2013. Electronic control in frustrated Lewis pair chemistry: adduct formation of intramolecular FLP systems with–P(C6F5)2 Lewis base components. Dalton Trans. 42, 4487–4499. ( 10.1039/C2DT32806B) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsoureas N, Kuo Y-Y, Haddow MF, Owen GR. 2011. Double addition of H2 to transition metal–borane complexes: a ‘hydride shuttle’ process between boron and transition metal centres. Chem. Commun. 47, 484–486. ( 10.1039/C0CC02245D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owen GR. 2016. Functional group migrations between boron and metal centres within transition metal–borane and –boryl complexes and cleavage of H–H, E–H and E' bonds. Chem. Commun. 52, 10 712–10 726. ( 10.1039/C6CC03817D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen GR. 2012. Hydrogen atom storage upon Z-class borane ligand functions: an alternative approach to ligand cooperation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 3535–3546. ( 10.1039/C2CS15346G) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harman WH, Peters JC. 2012. Reversible H2 addition across a nickel–borane unit as a promising strategy for catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 5080–5082. ( 10.1021/ja211419t) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fong H, Moret M-E, Lee Y, Peters JC. 2013. Heterolytic H2 cleavage and catalytic hydrogenation by an iron metallaboratrane. Organometallics 32, 3053–3062. ( 10.1021/om400281v) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnett BR, Moore CE, Rheingold AL, Figueroa JS. 2014. Cooperative transition metal/Lewis acid bond-activation reactions by a bidentate (boryl)iminomethane complex: a significant metal–borane interaction promoted by a small bite-angle LZ chelate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 10 262–10 265. ( 10.1021/ja505843g) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowie BE, Emslie DJH. 2014. Platinum complexes of a borane-appended analogue of 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene: flexible borane coordination modes and in situ vinylborane formation. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 16 899–16 912. ( 10.1002/chem.201404846) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devillard M, et al. 2016. A significant but constrained geometry Pt→Al interaction: fixation of CO2 and CS2, activation of H2 and PhCONH2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4917–4926. ( 10.1021/jacs.6b01320) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geri JB, Szymczak NK. 2015. A proton-switchable bifunctional ruthenium complex that catalyzes nitrile hydroboration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12 808–12 814. ( 10.1021/jacs.5b08406) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tseng K-NT, Kampf JW, Szymczak NK. 2016. Modular attachment of appended boron Lewis acids to a ruthenium pincer catalyst: metal–ligand cooperativity enables selective alkyne hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10 378–10 381. ( 10.1021/jacs.6b03972) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misumi Y, Seino H, Mizobe Y. 2009. Heterolytic cleavage of hydrogen molecule by rhodium thiolate complexes that catalyze chemoselective hydrogenation of imines under ambient conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 14 636–14 637. ( 10.1021/ja905835u) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohki Y, Sakamoto M, Tatsumi K. 2008. Reversible heterolysis of H2 mediated by an M–S(thiolate) bond (M = Ir, Rh): a mechanistic implication for [NiFe] hydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 11 610–11 611. ( 10.1021/ja804848w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao J, Li S. 2010. Theoretical study on the mechanism of H2 activation mediated by two transition metal thiolate complexes: homolytic for Ir, heterolytic for Rh. Dalton Trans. 39, 857–863. ( 10.1039/B910589A) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sweeney ZK, Polse JL, Andersen RA, Bergman RG, Kubinec MG. 1997. Synthesis, structure, and reactivity of monomeric titanocene sulfido and disulfide complexes. Reaction of H2 with a terminal M═S bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 4543–4544. ( 10.1021/ja970168t) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sweeney ZK, Polse JL, Bergman RG, Andersen RA. 1999. Dihydrogen activation by titanium sulfide complexes. Organometallics 18, 5502–5510. ( 10.1021/om9907876) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohki Y, Matsuura N, Marumoto T, Kawaguchi H, Tatsumi K. 2003. Heterolytic cleavage of dihydrogen promoted by sulfido-bridged tungsten−ruthenium dinuclear complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7978–7988. ( 10.1021/ja029941x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto T, Nakaya Y, Tatsumi K. 2008. Heterolytic dihydrogen activation by a sulfido- and oxo-bridged dinuclear germanium–ruthenium complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 1913–1915. ( 10.1002/anie.200704899) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochi N, Matsumoto T, Dei T, Nakao Y, Sato H, Tatsumi K, Sakaki S. 2015. Heterolytic activation of dihydrogen molecule by hydroxo-/sulfido-bridged ruthenium–germanium dinuclear complex. Theoretical insights. Inorg. Chem. 54, 576–585. ( 10.1021/ic502463y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campos J. 2017. Dihydrogen and acetylene activation by a gold(I)/platinum(0) transition metal only frustrated Lewis pair. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2944–2947. ( 10.1021/jacs.7b00491) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashmi ASK. 2007. Gold-catalyzed organic reactions. Chem. Rev. 107, 3180–3211. ( 10.1021/cr000436x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Z, Brouwer C, He C. 2008. Gold-catalyzed organic transformations. Chem. Rev. 108, 3239–3265. ( 10.1021/cr068434l) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bachmeier A, Esselborn J, Hexter SV, Krämer T, Klein K, Happe T, McGrady JE, Myers WK, Armstrong FA. 2015. How formaldehyde inhibits hydrogen evolution by [FeFe]-hydrogenases: determination by 13C ENDOR of direct Fe–C coordination and order of electron and proton transfers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 5381–5389. ( 10.1021/ja513074m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooke EJ, Evans RM, Islam STA, Roberts GM, Wehlin SAM, Carr SB, Phillips SEV, Armstrong FA. 2017. Importance of the active site canopy. Residues in an O2-tolerant [NiFe]-hydrogenase. Biochemistry 56, 132–142. ( 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00868) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volbeda A, Charon M-H, Piras C, Hatchikian EC, Frey M, Fontecilla-Camps JC. 1995. Crystal structure of the nickel–iron hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas. Nature 373, 580–587. ( 10.1038/373580a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volbeda A, Garcin E, Piras C, de Lacey AL, Fernandez VM, Hatchikian EC, Frey M, Fontecilla-Camps JC. 1996. Structure of the [NiFe] hydrogenase active site: evidence for biologically uncommon Fe ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 12 989–12 996. ( 10.1021/ja962270g) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters JW, Lanzilotta WN, Lemon BJ, Seefeldt LC. 1998. X-ray crystal structure of the Fe-only hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum to 1.8 angstrom resolution. Science 282, 1853–1858. ( 10.1126/science.282.5395.1853) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fontecilla-Camps JC, Volbeda A, Cavazza C, Nicolet Y. 2007. Structure/function relationships of [NiFe]- and [FeFe]-hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 107, 4273–4303. ( 10.1021/cr050195z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vincent KA, Parkin A, Armstrong FA. 2007. Investigating and exploiting the electrocatalytic properties of hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 107, 4366–4413. ( 10.1021/cr050191u) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cracknell JA, Vincent KA, Armstrong FA. 2008. Enzymes as working or inspirational electrocatalysts for fuel cells and electrolysis. Chem. Rev. 108, 2439–2461. ( 10.1021/cr0680639) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lubitz W, Ogata H, Rüdiger O, Reijerse E. 2014. Hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 114, 4081–4148. ( 10.1021/cr4005814) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee D-H, Patel BP, Clot E, Eisenstein O, Crabtree RH. 1999. Heterolytic dihydrogen activation in an iridium complex with a pendant basic group. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1999, 297–298. ( 10.1039/a808601j) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Camara JM, Rauchfuss TB. 2011. Mild redox complementation enables H2 activation by [FeFe]-hydrogenase models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8098–8101. ( 10.1021/ja201731q) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rauchfuss TB. 2015. Diiron azadithiolates as models for the [FeFe]-hydrogenase active site and paradigm for the role of the second coordination sphere. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2107–2116. ( 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00177) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camara JM, Rauchfuss TB. 2012. Combining acid–base, redox and substrate binding functionalities to give a complete model for the [FeFe]-hydrogenase. Nat. Chem. 4, 26–30. ( 10.1038/nchem.1180) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang N, Wang M, Wang Y, Zheng D, Han H, Ahlquist MSG, Sun L. 2013. Catalytic activation of H2 under mild conditions by an [FeFe]-hydrogenase model via an active μ-hydride species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13 688–13 691. ( 10.1021/ja408376t) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carroll ME, Barton BE, Rauchfuss TB, Carroll PJ. 2012. Synthetic models for the active site of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase: catalytic proton reduction and the structure of the doubly protonated intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18 843–18 852. ( 10.1021/ja309216v) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu T, Chen D, Hu X. 2015. Hydrogen-activating models of hydrogenases. Coord. Chem. Rev. 303, 32–41. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.05.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shima S, Vogt S, Göbels A, Bill E. 2010. Iron-chromophore circular dichroism of [Fe]-hydrogenase: the conformational change required for H2 activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 9917–9921. ( 10.1002/anie.201006255) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu T, Yin C-JM, Wodrich MD, Mazza S, Schultz KM, Scopelliti R, Hu X. 2016. A functional model of [Fe]-hydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 3270–3273. ( 10.1021/jacs.5b12095) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalz KF, Brinkmeier A, Dechert S, Mata RA, Meyer F. 2014. Functional model for the [Fe] hydrogenase inspired by the frustrated Lewis pair concept. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16 626–16 634. ( 10.1021/ja509186d) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogo S, et al. 2007. A dinuclear Ni(μ-H)Ru complex derived from H2. Science 316, 585–587. ( 10.1126/science.1138751) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ogo S, Ichikawa K, Kishima T, Matsumoto T, Nakai H, Kusaka K, Ohhara T. 2013. A functional [NiFe]hydrogenase mimic that catalyzes electron and hydride transfer from H2. Science 339, 682–684. ( 10.1126/science.1231345) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manor BC, Rauchfuss TB. 2013. Hydrogen activation by biomimetic [NiFe]-hydrogenase model containing protected cyanide cofactors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11 895–11 900. ( 10.1021/ja404580r) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohkuma T, Ooka H, Hashiguchi S, Ikariya T, Noyori R. 1995. Practical enantioselective hydrogenation of aromatic ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 2675–2676. ( 10.1021/ja00114a043) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hashiguchi S, Fujii A, Takehara J, Ikariya T, Noyori R. 1995. Asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of aromatic ketones catalyzed by chiral ruthenium(II) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 7562–7563. ( 10.1021/ja00133a037) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Noyori R, Ohkuma T. 2001. Asymmetric catalysis by architectural and functional molecular engineering: practical chemo- and stereoselective hydrogenation of ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 40–73. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noyori R. 2002. Asymmetric catalysis: science and opportunities (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 2008–2022. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Noyori R, Yamakawa M, Hashiguchi S. 2001. Metal–ligand bifunctional catalysis: a nonclassical mechanism for asymmetric hydrogen transfer between alcohols and carbonyl compounds. J. Org. Chem. 66, 7931–7944. ( 10.1021/jo010721w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dub PA, Ikariya T. 2013. Quantum chemical calculations with the inclusion of nonspecific and specific solvation: asymmetric transfer hydrogenation with bifunctional ruthenium catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2604–2619. ( 10.1021/ja3097674) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zuo W, Lough AJ, Li Y, Morris RH. 2013. Amine(imine)diphosphines activate iron catalysts in the asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of ketones and imines. Science 342, 1080–1083. ( 10.1126/science.1244466) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morris RH. 2015. Exploiting metal–ligand bifunctional reactions in the design of iron asymmetric hydrogenation catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1494–1502. ( 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00045) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Prokopchuk DE, Morris RH. 2012. Inner-sphere activation, outer-sphere catalysis: theoretical study on the mechanism of transfer hydrogenation of ketones using iron(II) PNNP eneamido complexes. Organometallics 31, 7375–7385. ( 10.1021/om300572v) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hayes JM, Deydier E, Ujaque G, Lledós A, Malacea-Kabbara R, Manoury E, Vincendeau S, Poli R. 2015. Ketone hydrogenation with iridium complexes with non N–H ligands: the key role of the strong base. ACS Catal. 5, 4368–4376. ( 10.1021/acscatal.5b00613) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dub PA, Henson NJ, Martin RL, Gordon JC. 2014. Unravelling the mechanism of the asymmetric hydrogenation of acetophenone by [RuX2(diphosphine)(1,2-diamine)] catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 3505–3521. ( 10.1021/ja411374j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dub PA, Scott BL, Gordon JC. 2017. Why does alkylation of the N–H functionality within M/NH bifunctional Noyori-type catalysts lead to turnover? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1245–1260. ( 10.1021/jacs.6b11666) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dub PA, Gordon JC. 2016. The mechanism of enantioselective ketone reduction with Noyori and Noyori–Ikariya bifunctional catalysts. Dalton Trans. 45, 6756–6781. ( 10.1039/C6DT00476H) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zuo W, Tauer S, Prokopchuk DE, Morris RH. 2014. Iron catalysts containing amine(imine)diphosphine P-NH-N-P ligands catalyze both the asymmetric hydrogenation and asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of ketones. Organometallics 33, 5791–5801. ( 10.1021/om500479q) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Curtis CJ, Miedaner A, Ciancanelli R, Ellis WW, Noll BC, Rakowski DuBois M, DuBois DL. 2003. [Ni(Et2PCH2NMeCH2PEt2)2]2+ as a functional model for hydrogenases. Inorg. Chem. 42, 216–227. ( 10.1021/ic020610v) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Franz JA, et al. 2013. Conformational dynamics and proton relay positioning in nickel catalysts for hydrogen production and oxidation. Organometallics 32, 7034–7042. ( 10.1021/om400695w) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilson AD, Newell RH, McNevin MJ, Muckerman JT, Rakowski DuBois M, DuBois DL. 2006. Hydrogen oxidation and production using nickel-based molecular catalysts with positioned proton relays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 358–366. ( 10.1021/ja056442y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hou J, Fang M, Cardenas AJP, Shaw WJ, Helm ML, Bullock RM, Roberts JAS, O'Hagan M. 2014. Electrocatalytic H2 production with a turnover frequency >107s−1: the medium provides an increase in rate but not overpotential. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 4013–4017. ( 10.1039/c4ee01899k) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cardenas AJP, Ginovska B, Kumar N, Hou J, Raugei S, Helm ML, Appel AM, Bullock RM, O'Hagan M. 2016. Controlling proton delivery through catalyst structural dynamics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 13 509–13 513. ( 10.1002/anie.201607460) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Raugei S, Helm ML, Hammes-Schiffer S, Appel AM, O'Hagan M, Wiedner ES, Bullock RM. 2016. Experimental and computational mechanistic studies guiding the rational design of molecular electrocatalysts for production and oxidation of hydrogen. Inorg. Chem. 55, 445–460. ( 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02262) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raugei S, Chen S, Ho MH, Ginovska-Pangovska B, Rousseau RJ, Dupuis M, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. 2012. The role of pendant amines in the breaking and forming of molecular hydrogen catalyzed by nickel complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 6493–6506. ( 10.1002/chem.201103346) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang JY, Smith SE, Liu T, Dougherty WG, Hoffert WA, Kassel WS, Rakowski DuBois M, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. 2013. Two pathways for electrocatalytic oxidation of hydrogen by a nickel bis(diphosphine) complex with pendant amines in the second coordination sphere. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9700–9712. ( 10.1021/ja400705a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Crabtree RH. 2016. Dihydrogen complexation. Chem. Rev. 116, 8750–8769. ( 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kubas GJ. 2007. Fundamentals of H2 binding and reactivity on transition metals underlying hydrogenase function and H2 production and storage. Chem. Rev. 107, 4152–4205. ( 10.1021/cr050197j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heinekey DM, Oldham WJ Jr. 1993. Coordination chemistry of dihydrogen. Chem. Rev. 93, 913–926. ( 10.1021/cr00019a004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang JY, Bullock RM, Shaw WJ, Twamley B, Fraze K, Rakowski DuBois M, DuBois DL. 2009. Mechanistic insights into catalytic H2 oxidation by Ni complexes containing a diphosphine ligand with a positioned amine base. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 5935–5945. ( 10.1021/ja900483x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stolley RM, Darmon JM, Das P, Helm ML. 2016. Nickel bis-diphosphine complexes: controlling the binding and heterolysis of H2. Organometallics 35, 2965–2974. ( 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00486) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wiedner ES, Chambers MB, Pitman CL, Bullock RM, Miller AJM, Appel AM. 2016. Thermodynamic hydricity of transition metal hydrides. Chem. Rev. 116, 8655–8692. ( 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00168) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kaljurand I, Rodima T, Leito I, Koppel IA, Schwesinger R. 2000. Self-consistent spectrophotometric basicity scale in acetonitrile covering the range between pyridine and DBU. J. Org. Chem. 65, 6202–6208. ( 10.1021/jo005521j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kaljurand I, Kutt A, Soovali L, Rodima T, Maemets V, Leito I, Koppel IA. 2005. Extension of the self-consistent spectrophotometric basicity scale in acetonitrile to a full span of 28 pKa units: unification of different basicity scales. J. Org. Chem. 70, 1019–1028. ( 10.1021/jo048252w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wayner DDM, Parker VD. 1993. Bond energies in solution from electrode potentials and thermochemical cycles. A simplified and general approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 26, 287–294. ( 10.1021/ar00029a010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Connelly SJ, Wiedner ES, Appel AM. 2015. Predicting the reactivity of hydride donors in water: thermodynamic constants for hydrogen. Dalton Trans. 44, 5933–5938. ( 10.1039/C4DT03841J) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bullock RM, Appel AM, Helm ML. 2014. Production of hydrogen by electrocatalysis: making the H–H bond by combining protons and hydrides. Chem. Commun. 50, 3125–3143. ( 10.1039/c3cc46135a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kilgore U, et al. 2011. Ni(PPh2NC6H4X2)2](BF4)2 complexes as electrocatalysts for H2 production: effect of substituents, acids, and water on catalytic rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 5861–5872. ( 10.1021/ja109755f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kilgore UJ, Stewart MP, Helm ML, Dougherty WG, Kassel WS, Rakowski DuBois M, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. 2011. Studies of a series of [Ni(PR2NPh2)2(CH3CN)]2+ complexes as electrocatalysts for H2 production: substituent variation at the phosphorus atom of the P2N2 ligand. Inorg. Chem. 50, 10 908–10 918. ( 10.1021/ic201461a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu T, Chen S, O'Hagan MJ, Rakowski DM, Bullock RM, DuBois DL. 2012. Synthesis, characterization and reactivity of Fe complexes containing cyclic diazadiphosphine ligands: the role of the pendant base in heterolytic cleavage of H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 6257–6272. ( 10.1021/ja211193j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu T, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. 2013. An iron complex with pendent amines as a molecular electrocatalyst for oxidation of hydrogen. Nat. Chem. 5, 228–233. ( 10.1038/nchem.1571) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liu T, Liao Q, O'Hagan M, Hulley EB, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. 2015. Iron complexes bearing diphosphine ligands with positioned pendant amines as electrocatalysts for the oxidation of H2. Organometallics 34, 2747–2764. ( 10.1021/om501289f) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu T, Wang X, Hoffmann C, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. 2014. Heterolytic cleavage of hydrogen by an iron hydrogenase model: an Fe–H···H–N dihydrogen bond characterized by neutron diffraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5300–5304. ( 10.1002/anie.201402090) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Richardson T, de Gala S, Crabtree RH, Siegbahn PEM. 1995. Unconventional hydrogen bonds: intermolecular B–H···H–N interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 12 875–12 876. ( 10.1021/ja00156a032) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Custelcean R, Jackson JE. 2001. Dihydrogen bonding: structures, energetics, and dynamics. Chem. Rev. 101, 1963–1980. ( 10.1021/cr000021b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Crabtree RH, Siegbahn PEM, Eisenstein O, Rheingold AL, Koetzle TF. 1996. A new intermolecular interaction: unconventional hydrogen bonds with element–hydride bonds as proton acceptor. Acc. Chem. Res. 29, 348–354. ( 10.1021/ar950150s) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Darmon JM, Raugei S, Liu T, Hulley EB, Weiss CJ, Bullock RM, Helm ML. 2014. Iron complexes for the electrocatalytic oxidation of hydrogen: tuning primary and secondary coordination spheres. ACS Catal. 4, 1246–1260. ( 10.1021/cs500290w) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Darmon JM, Kumar N, Hulley EB, Weiss CJ, Raugei S, Bullock RM, Helm ML. 2015. Increasing the rate of hydrogen oxidation without increasing the overpotential: a bio-inspired iron molecular electrocatalyst with an outer coordination sphere proton relay. Chem. Sci. 6, 2737–2745. ( 10.1039/C5SC00398A) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.King WA, Luo X-L, Scott BL, Kubas GJ, Zilm KW. 1996. Cationic manganese(I) dihydrogen and dinitrogen complexes derived from a formally 16-electron complex with a bis-agostic interaction, [Mn(CO)(Ph2PC2H4PPh2)2]+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 6782–6783. ( 10.1021/ja960499q) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.King WA, Scott BL, Eckert J, Kubas GJ. 1999. Reversible displacement of polyagostic interactions in 16e [Mn(CO)(R2PC2H4PR2)2]+ by H2, N2, and SO2. Binding and activation of η2-H2 trans to CO is nearly invariant to changes in charge and cis ligands. Inorg. Chem. 38, 1069–1084. ( 10.1021/ic981263l) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Welch KD, Dougherty WG, Kassel WS, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. 2010. Synthesis, structures, and reactions of manganese complexes containing diphosphine ligands with pendant amines. Organometallics 29, 4532–4540. ( 10.1021/om100668e) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hulley EB, Welch KD, Appel AM, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. 2013. Rapid, reversible heterolytic cleavage of bound H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11– . 736–11 739. ( 10.1021/ja405755j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hulley EB, Helm ML, Bullock RM. 2014. Heterolytic cleavage of H2 by bifunctional manganese(I) complexes: impact of ligand dynamics, electrophilicity, and base positioning. Chem. Sci. 5, 4729–4741. ( 10.1039/C4SC01801J) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hulley EB, Kumar N, Raugei S, Bullock RM. 2015. Manganese-based molecular electrocatalysts for oxidation of hydrogen. ACS Catal. 5, 6838–6847. ( 10.1021/acscatal.5b01751) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bullock RM, Voges MH. 2000. Homogeneous catalysis with inexpensive metals: ionic hydrogenation of ketones with molybdenum and tungsten catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 12– . 594–12 595. ( 10.1021/Ja0010599) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Voges MH, Bullock RM. 2002. Catalytic ionic hydrogenations of ketones using molybdenum and tungsten complexes. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2002, 759–770. ( 10.1039/b107754f) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bullock RM. 2004. Catalytic ionic hydrogenations. Chem. Eur. J. 10, 2366–2374. ( 10.1002/chem.200305639) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang S, Bullock RM. 2015. Molybdenum hydride and dihydride complexes bearing diphosphine ligands with a pendant amine: formation of complexes with bound amines. Inorg. Chem. 54, 6397–6409. ( 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00728) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang S, Appel AM, Bullock RM. 2017. Reversible heterolytic cleavage of the H–H bond by molybdenum complexes: controlling the dynamics of exchange between proton and hydride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7376–7387. ( 10.1021/jacs.7b03053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.