Abstract

In this concept article, we consider the notion of ‘frustrated Lewis pairs’ (FLPs). While the original use of the term referred to steric inhibition of dative bond formation in a Lewis pair, work in the intervening decade demonstrates the limitation of this simplistic view. Analogies to known transition metal chemistry and the applications in other areas of chemistry are considered. In the light of these findings, we present reflections on the criteria for a definition of the term ‘frustrated Lewis pair’. Segregation of the Lewis acid and base and the kinetic nature of FLP reactivity are discussed. We are led to the conclusion that, while an all-inclusive definition of FLP is challenging, the notion of ‘FLP chemistry’ is more readily recognized.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘Frustrated Lewis pair chemistry’.

Keywords: frustrated Lewis pair chemistry, segregation of Lewis acid and base, main group chemistry

1. Introduction

As early as 1942, H.C. Brown had noted that the combination of the donor and acceptor lutidine and BMe3 failed to form a classical Lewis acid–base adduct (figure 1) [1]. Brown contrasted this combination with that of lutidine and BF3, which forms a dative bond, and rationalized the former anomaly on the basis of steric congestion. Two decades later, reactions in which donor and acceptor reacted with a substrate emerged. Wittig & Benz [2] described the reactions of BPh3 and PPh3 with benzyne, to give the zwitterionic addition product (C6H4)(BPh3)(PPh3). Tochtermann [3] described a similar addition reaction of trityl anion and BPh3 to butadiene to give 1,2- and 1,4-addition products [Ph3CCH2CH(BPh3)CH═CH2]− and [Ph3CCH2CH═CHCH2(BPh3)]− (figure 1). These systems were described as an ‘antagonistic pair, although further reactivity was not reported.

Figure 1.

Historical timeline leading to the early development of FLP chemistry. (Online version in colour.)

In the late 1990s, it was Piers' insightful description of the B(C6F5)3-catalysed hydrosilylation of ketones [4] that is now recognized as the first example of what has come to be known as ‘frustrated Lewis pair’ (FLP) chemistry (figure 1). In this case, contrary to expectations, Piers showed that it was the activation of the Si–H bond by B(C6F5)3 and subsequent attack by ketone that effected this catalysis. Thus, the basic ketone and the Lewis acidic borane act in concerted fashion on the Si–H bond. This mechanism was subsequently substantiated by the elegant work of Oestreich and co-workers [5] in which they used a chiral silane to confirm the inversion of stereochemistry at Si. This cooperative action of the donor and acceptor on the Si–H bond foreshadowed the finding of the FLP activation of H2 that occured 10 years later.

Now part of some freshman chemistry curricula, the common understanding is that on FLP is a compound or mixture containing a Lewis acid and a Lewis base that, because of steric hindrance or geometry constraints, cannot combine to form a classical Lewis adduct. This definition emerged as a result of the initial examples of FLP systems capable of the activation of H2, including Mes2P(C6F4)B(C6F5)2 [6], Mes2PCH2CH2B(C6F5)2 [7] and combinations of bulky phosphines (e.g. tBu3P, Mes3P) with B(C6F5)3 [8] (figure 1). However, over the past decade, the range of examples of FLP systems has broadened dramatically. A number of these systems point to the limitations of this simple definition.

This concept article was prompted a few years ago when one of the authors (F.-G. F.) read the following question on a popular science blog: ‘How do you synthesize a frustrated Lewis pair (FLP)?’ Initially, this question brought a smile, as intermolecular FLPs are generated simply from the combination of commercially available Lewis acids and bases. But lurking behind the seeming naiveté of this question and its answer, is a deeper, more profound fundamental question, for which the full answer is far from trivial: What constitutes an FLP? In this article, we consider the evidence and attempt to provide broader considerations of the features that give rise to FLP chemistry. At the same time, we highlight the relationship of FLP chemistry to ‘classical’ main group and organometallic chemistry. As a pedagogical tool, we hope these considerations will clarify the nature of FLPs. After a decade of FLP chemistry, it is our hope that this account will provide a clearer perspective to newcomers to the field and prompt discussions among specialists.

2. Discussion

The term ‘frustrated Lewis pair’ was coined in 2007 [9], a year after the finding that Mes2P(C6F4)B(C6F5)2 reacted reversibly with molecular hydrogen under very mild conditions [6]. This reaction was remarkable, as, prior to that time, reversible reactions with H2 had been limited to transition metal chemistry. In the ensuing year, it was shown that simple combinations of sterically encumbered phosphines and boranes effected similar activations of H2 [8]. Moreover, this reactivity was also extended to intramolecular FLPs as well as to metal-free hydrogenation catalysis [10]. However, it was the further expansion of the reactivity of FLPs to reactions with olefins that prompted the first use of the term ‘frustrated Lewis pair’ [9]. Collectively, these observations had made it clear that sterically precluding or ‘frustrating’ dative bond formation offered a unique route to new reactivity, and thus the field of FLP chemistry was born.

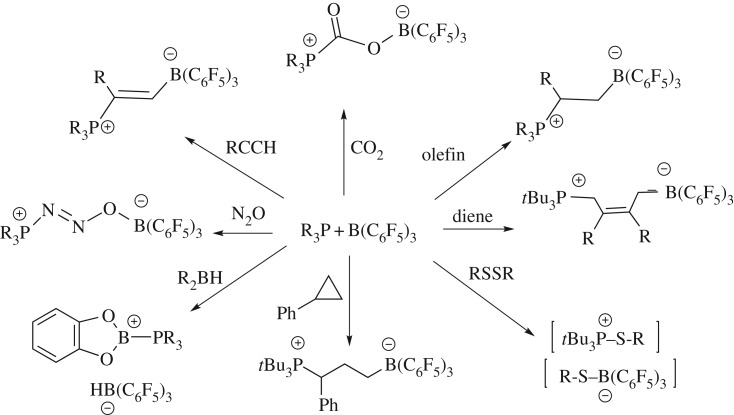

In the past decade, many examples of both intramolecular and intermolecular FLPs have emerged and been shown to activate hydrogen and react with an ever-widening variety of other substrates (figure 2) [11–13]. While many of these advances have exploited the typical bulky phosphines and B(C6F5)3 (figure 2), this chemistry has also been broadly expanding to include a range of Lewis bases derived from B, C, N, O, S, Se and Te donors, with Lewis acids based on B, Al, Ga, In, C, Si, Sn, N and P(V) [14]. Such developments have uncovered new reactivity of main group systems and led to advances in metal-free catalysis [15].

Figure 2.

Examples of FLP chemistry with phosphine/borane combinations.

The concept is also finding analogies and applications in a number of other areas of chemical science beyond main group chemistry [16]. Early applications of the concept have found applications in organic, polymer and radical synthesis, while applications of the notion of FLPs to transition metal-based systems have also emerged [16]. More recently, further applications of the concept have been used to rationalize the mechanisms of reactions in the diverse areas of materials chemistry, heterogeneous catalysis and enzymatic chemistry.

(a). Analogy to metal and enzyme systems

The mechanism of FLP activation of H2 bears a close resemblance to the mechanism of action of the Noyori-type catalysts [17]. The latter system reacts with H2, affording concerted transfer of a proton to N and a hydride to the metal centre (figure 3a). In that sense, the Noyori-bifunctional activation of H2 involves the basic N and the Lewis acidic metal centre. In the same vein, the reactivity of FLPs, particularly with H2, is reminiscent of concerted oxidative addition of H2 to a transition metal. In that case, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the metal accepts the electrons from the H2 σ-bond, while the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the metal donates electron density to the σ*-orbital of the H–H bond. Of course, in the case of oxidative addition to a metal centre, the HOMO and LUMO reside on the same atom; whereas in FLP chemistry, the donor and acceptor orbitals reside on disparate atoms. Thus, one can draw a parallel between the required orthogonality of the filled and empty orbitals on a transition metal needed for oxidative addition and the ‘frustration’ required for an FLP to ensure the accessibility of donor and acceptor orbitals.

Figure 3.

Metal and enzyme systems analogous to FLP reactivity: (a) Noyori catalyst; (b) Bullock models of Ni-hydrogenase; (c) conversion of guanylylpyridinol cofactor to methylenetetrahydromethanopterin and a proton by Fe-hydrogenase.

One can also draw parallels between FLP reactivity and enzymatic processes. At some level, a role of protein structure is to provide binding sites for electron-rich and electron-deficient centres and at the same time maintain separation, so that redox chemistry can occur in an orchestrated fashion. In that sense, enzymes are nature's FLPs. A more direct similarity is derived from Ni–Fe, Fe–Fe or Fe-only hydrogenases [18–20]. The Fe–Fe enzyme effects the reversible oxidation of H2 to protons, via the cooperative action of an electron-deficient metal centre and a pendant non-coordinating N donor modelled by Dubois and Bullock (figure 3b). Similarly, the [Fe] hydrogenase heterolytically splits H2 to deliver a hydride to mononuclear Fe-guanylylpyridinol cofactor, affording methylenetetrahydromethanopterin and a proton (figure 3c). These examples point to the role of non-metal species in the cleavage of H2, but moreover emphasize the importance of the restricted approach of the electron acceptor and donor provided by the protein structure.

(b). Segregation of donor and acceptor

The presence of a Lewis acid and base in close proximity to a substrate allows for two-electron transfer cascade reactions to occur. Whether it is the activation of H2, alkenes, carbon dioxide or C–H bonds, the common feature of all these transformations is the transfer of two electrons from the HOMO of the Lewis base to a substrate, which in turn transfers two electrons to the LUMO of the Lewis acid. Interestingly, the relative energies of the HOMO and LUMO are tuned by selection of the respective Lewis acid and base. Moreover, in the case of H2 activation, the bond strengths of the resulting protonated Lewis donor and the hydride on the Lewis acceptor will determine the driving force of proton and hydride delivery in a catalytic process. Lewis acidic species, such as B(C6F5)3, will be quite effective at H2 cleavage, but hydride delivery to a substrate for hydrogenation will be slowed by the relatively strong B–H bond strength. Conversely, the use of weak Lewis bases will generate strongly acidic protons facilitating protonation of a substrate driving subsequent hydride delivery.

Many ambiphilic systems activate bonds through a concerted mechanism in which a low barrier is associated with the availability of resonance forms and electron delocalization between the nucleophilic and electrophilic centres. Indeed, all reactions involve the migration of electron density from an electron-rich centre to an electron-poor one and yet clearly not all reactions would be considered FLP reactions. Thus, the question is, what is distinct about FLP reactivity? One could consider the idea that an FLP reaction begins with segregated donor and acceptor sites. While such segregation is clearly the case for many FLP systems, there are certainly some systems that exhibit FLP chemistry in which separation of donor and acceptor is transiently masked by dative interactions. For example, in the case of lutidine and B(C6F5)3 (figure 4), a classical Lewis acid–base adduct is present in the mixture [21]. Nonetheless, this adduct exists in an equilibrium with the free base and acid. This allows access to the segregated donor and acceptor sites that initiate FLP reactivity.

Figure 4.

Examples of FLP systems that are not ‘sterically frustrated’.

That being said, is segregation of the donor and acceptor sites the key feature that defines FLP reactivity? While this certainly encircles many of the obvious cases, the species R2PB(C6F5)2 were shown to react with H2 (figure 4) [22]. This reactivity was attributed to the energetic mismatch between the lone pair of electrons on P and the acceptor orbital on B. This mismatch ‘segregates’ the nucleophile and the electrophile, allowing the reaction with H2 to proceed. Perhaps an extreme case is to consider the reaction of cyclic amino alkyl carbenes (CAAC) with H2 [23]. Here, in that case, the donor and acceptor are located on the same carbon atom. Is this an FLP reaction? Certainly, there is an analogy, although one could also describe this as a formal concerted oxidative addition where the HOMO and LUMO are orthogonal on a single atom, highlighting a grey zone between FLPs and this chemistry. Thus, we must conclude that systems that comprise segregated Lewis acid and base centres may be obvious FLPs. However, other systems point to the deficiencies of this feature as the sole criterion for the definition of an FLP. Nevertheless, all these reactions have Lewis acid and base centres that are not mutually neutralized when reaction occurs, suggesting that FLPs are defined by their reactivity rather than by their structural features.

(c). A kinetic phenomenon

In 2014, Stephan and co-workers [24] and Ashley and co-workers [25] simultaneously reported the hydrogenation of ketones using B(C6F5)3 in ethereal solvents. In these cases, the solvent, an ether, acts as the Lewis base in concert with the Lewis acid to effect H2 activation (figure 5). This stands in apparent conflict with the known ability of B(C6F5)3 to form stable ether adducts. Similarly, Repo and co-workers [26,27] and Fontaine and co-workers [28–30] reported catalytic processes with amine-boranes of the type R2NC6H4BH2 where the Lewis acid is neutralized by formation of either intermolecular Lewis adduct or two-electron–three-centre bonds. Even the least sterically encumbered analogue, Me2NC6H4BH2, which exists as a dimeric species, exhibits reactivity typical of FLP chemistry [31]. These findings further illustrate that prior segregation of the Lewis acid and base is but one sufficient avenue to FLP reactivity. However, it is certainly not required. What emerges from these findings is the notion that FLP reactivity may be accessed by an equilibrium, which provides access to the transiently free Lewis acid and base. Even if the equilibrium constant is small, reaction of the free species with H2 or other substrates provides an avenue to FLP reactivity via Le Chatelier's principle. This perspective on FLP chemistry thus de-emphasizes the role of steric ‘frustration’. The importance of transient FLP species was also demonstrated in 2013 by Fontaine and co-workers when they reported the hydroboration of carbon dioxide by ambiphilic phosphine-borane FLP catalysts [32,33]. This catalyst did not react independently with hydridoboranes or carbon dioxide, yet catalysis did occur. This illustrates that favourable kinetics for the concerted action of the Lewis partners on a substrate can overcome the apparent neutralization of Lewis acid and base. In this sense, FLP chemistry should be viewed as a kinetic phenomenon.

Figure 5.

Example of sterically unhindered FLPs.

Returning to the question ‘what is an FLP?’, it is clear that a formal definition that provides for the variety of systems described to date remains challenging. Thus, one is left with the seemingly trivial conclusion that an FLP is a combination of a Lewis acid and base that exhibits FLP chemistry. The notion of FLP chemistry can be more straightforwardly defined. Indeed, all known examples conform to the notion that FLP chemistry involves the concerted action of a Lewis acid and base segregated at the transition state on a substrate molecule.

3. Conclusion

Above we considered the initial notion that an FLP is a combination of a Lewis acid and base that do not form an adduct. It is clear that this ‘definition’ does not encompass all the systems that exhibit FLP chemistry. A considerable breadth of known FLP systems comprise Lewis acid–base combinations where dative bonding is thermodynamically favoured. Nonetheless, such seemingly classical Lewis pairs access the free components via dissociative equilibria and thus realize FLP reactivity. This chemistry is more readily defined as a kinetic phenomenon in which a Lewis acid and base act on a substrate molecule. Thus, while an all-encompassing definition of the term ‘frustrated Lewis pair’ remains elusive, ‘FLP chemistry’ is more readily recognized. The focus on the chemistry seems fitting. The original findings extended reactivity with H2 to areas of the periodic table where this was previously unknown, and indeed the potential for future impact of this area of chemistry lies in its ability to stimulate the discovery of new reactivity.

Data accessibility

There are no supplementary data for this article.

Authors' contributions

F.-G.F. and D.W.S. wrote this in a joint effort.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

F.-G.F. and D.W.S. thank NSERC of Canada for financial support. D.W.S. is also grateful to NSERC of Canada for the award of a Canada Research Chair and to the Einstein Foundation for the award of an Einstein Fellowship.

References

- 1.Brown HC, Schlesinger HI, Cardon SZ. 1942. Studies in stereochemistry. I. Steric strains as a factor in the relative stability of some coordination compounds of boron. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 64, 325–329. ( 10.1021/ja01254a031) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittig G, Benz E. 1959. Über das Verhalten von Dehydrobenzol gegenüber nucleophilen und elektrophilen Reagenzien. Chem. Ber. 92, 1999–2013. ( 10.1002/cber.19590920904) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tochtermann W. 1966. Structures and reactions of organic ate- complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 5, 351–371. ( 10.1002/anie.196603511) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parks DJ, Piers WE. 1996. Tris(pentafluorophenyl)boron-catalyzed hydrosilation of aromatic aldehydes, ketones, and esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 9440–9441. ( 10.1021/ja961536g) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rendler S, Oestreich M. 2008. Conclusive evidence for an SN2-Si mechanism in the B(C6F5)3-catalyzed hydrosilylation of carbonyl compounds: implications for the related hydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 5997–6000. ( 10.1002/anie.200801675) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welch GC, Juan RRS, Masuda JD, Stephan DW. 2006. Reversible, metal-free hydrogen activation. Science 314, 1124–1126. ( 10.1126/science.1134230) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spies P, Erker G, Kehr G, Bergander K, Fröhlich R, Grimme S, Stephan DW. 2007. Rapid intramolecular heterolytic dihydrogen activation by a four-membered heterocyclic phosphane–borane adduct. Chem. Commun. 2007, 5072–5074. ( 10.1039/B710475h) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welch GC, Stephan DW. 2007. Facile heterolytic cleavage of dihydrogen by phosphines and boranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1880–1881. ( 10.1021/ja067961j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCahill JSJ, Welch GC, Stephan DW. 2007. Reactivity of ‘frustrated Lewis pairs': three-component reactions of phosphines, a borane, and olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 4968–4971. ( 10.1002/anie.200701215) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chase PA, Welch GC, Jurca T, Stephan DW. 2007. Metal-free catalytic hydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 8050–8053. ( 10.1002/anie.200702908) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stephan DW, Erker G. 2015. Frustrated Lewis pair chemistry: development and perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 6400–6441. ( 10.1002/anie.201409800) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephan DW. 2015. Frustrated Lewis pairs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10 018–10 032. ( 10.1021/jacs.5b06794) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephan DW. 2015. Frustrated Lewis pairs: from concept to catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 306–316. ( 10.1021/ar500375j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weicker SA, Stephan DW. 2015. Main group Lewis acids in frustrated Lewis pair chemistry: beyond electrophilic boranes. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 88, 1003–1016. ( 10.1246/bcsj.20150131) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fontaine F-G, Courtemanche M-A, Légaré M-A, Rochette É. 2017. Design principles in frustrated Lewis pair catalysis for the functionalization of carbon dioxide and heterocycles. Coord. Chem. Rev. 334, 124–135. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2016.05.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephan DW. 2016. The broadening reach of frustrated Lewis pair chemistry. Science 354, aaf7229 ( 10.1126/science.aaf7229) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noyori R. 2002. Asymmetric catalysis: science and opportunities (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 2008–2022. ( 10.1002/1521-3773(20020617)41:12%3C2008::aid-anie2008%3E3.0.co;2-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bullock RM, Helm ML. 2015. Molecular electrocatalysts for oxidation of hydrogen using Earth-abundant metals: shoving protons around with proton relays. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2017–2026. ( 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00069) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raugei S, Chen ST, Ho MH, Ginovska-Pangovska B, Rousseau RJ, Dupuis M, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. 2012. The role of pendant amines in the breaking and forming of molecular hydrogen catalyzed by nickel complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 6493–6506. ( 10.1002/chem.201103346) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shima S, Pilak O, Vogt S, Schick M, Stagni MS, Meyer-Klaucke W, Warkentin E, Thauer RK, Ermler U. 2008. The crystal structure of [Fe]-hydrogenase reveals the geometry of the active site. Science 321, 572–575. ( 10.1126/science.1158978) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geier SJ, Stephan DW. 2009. Lutidine/B(C6F5)3: at the boundary of classical and frustrated Lewis pair reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3476–3477. ( 10.1021/ja900572x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geier SJ, Gilbert TM, Stephan DW. 2008. Activation of H2 by phosphinoboranes R2PB(C6F5)2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 12 632–12 633. ( 10.1021/ja805493y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frey GD, Lavallo V, Donnadieu B, Schoeller WW, Bertrand G. 2007. Carbenes reacting like metals, oxidative addition of H2 and NH3. Science 316, 439–441. ( 10.1126/science.1141474) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahdi T, Stephan DW. 2014. Enabling catalytic ketone hydrogenation by frustrated Lewis pairs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 15 809–15 812. ( 10.1021/ja508829x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott DJ, Fuchter MJ, Ashley AE. 2014. Nonmetal catalyzed hydrogenation of carbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15 813–15 816. ( 10.1021/ja5088979) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chernichenko K, Kotai B, Papai I, Zhivonitko V, Nieger M, Leskela M, Repo T. 2015. Intramolecular frustrated Lewis pair with the smallest boryl site: reversible H2 addition and kinetic analysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 1749–1753. ( 10.1002/anie.201410141) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chernichenko K, Lindqvist M, Kotai B, Nieger M, Sorochkina K, Papai I, Repo T. 2016. Metal-free sp2-C–H borylation as a common reactivity pattern of frustrated 2-aminophenylboranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4860–4868. ( 10.1021/jacs.6b00819) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Legare MA, Courtemanche MA, Rochette E, Fontaine FG. 2015. Metal-free catalytic C–H bond activation and borylation of heteroarenes. Science 349, 513–516. ( 10.1126/science.aab3591) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Legare MA, Rochette E, Legare Lavergne J, Bouchard N, Fontaine FG. 2016. Bench-stable frustrated Lewis pair chemistry: fluoroborate salts as precatalysts for the C–H borylation of heteroarenes. Chem. Commun. 52, 5387–5390. ( 10.1039/c6cc01267a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bose SK, Marder TB. 2015. A leap ahead for activating C–H bonds. Science 349, 473–474. ( 10.1126/science.aac9244) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rochette E, Bouchard N, Legare Lavergne J, Matta CF, Fontaine FG. 2016. Spontaneous reduction of a hydroborane to generate a B–B single bond by the use of a Lewis pair. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12 722–12 726. ( 10.1002/anie.201605645) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Courtemanche MA, Legare MA, Maron L, Fontaine FG. 2013. A highly active phosphine–borane organocatalyst for the reduction of CO2 to methanol using hydroboranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9326–9329. ( 10.1021/ja404585p) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Declercq R, Bouhadir G, Bourissou D, Légaré M-A, Courtemanche M-A, Nahi KS, Bouchard N, Fontaine F-G, Maron L. 2015. Hydroboration of carbon dioxide using ambiphilic phosphine–borane catalysts: on the role of the formaldehyde adduct. ACS Catal. 5, 2513–2520. ( 10.1021/acscatal.5b00189) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no supplementary data for this article.