Abstract

Evidence from animal species indicates that a male-biased adult sex ratio (ASR) can lead to higher levels of male parental investment and that there is heterogeneity in behavioural responses to mate scarcity depending on mate value. In humans, however, there is little consistent evidence of the effect of the ASR on pair-bond stability and parental investment and even less of how it varies by an individual's mate value. In this paper we use detailed census data from Northern Ireland to test the association between the ASR and pair-bond stability and parental investment by social status (education and social class) as a proxy for mate value. We find evidence that female, but not male, cohabitation is associated with the ASR. In female-biased areas women with low education are less likely to be in a stable pair-bond than highly educated women, but in male-biased areas women with the lowest education are as likely to be in a stable pair-bond as their most highly educated peers. For both sexes risk of separation is greater at female-biased sex ratios. Lastly, our data show a weak relationship between parental investment and the ASR that depends on social class. We discuss these results in the light of recent reformulations of parental investment theory.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘Adult sex ratios and reproductive decisions: a critical re-examination of sex differences in human and animal societies’.

Keywords: adult sex ratio, mating, parental investment, heterogeneity, humans

1. Introduction

The adult sex ratio (ASR) has important consequences for mating-related behaviours. When one sex has many potential partners and the other has few, the mate-limiting sex can increase demands on prospective mates. Various responses in mating and reproductive behaviours to a skewed ASR have been observed across species; male-biased sex ratios are associated with higher levels of copulation and faster sperm depletion in fruit flies and snow crabs [1,2], higher levels of mate-guarding in spiders, crustaceans and water striders [3,4], and increased male allocations to parenting rather than mating effort through lower levels of polygyny and divorce across shorebird species [5]. In humans, there is evidence that male-biased sex ratios are associated with later reproduction, lower rates of single motherhood, a lower preference for short-term sexual relationships, and relatively fewer sexual partners for both men and women [6–12]. However, inconclusive or contradictory evidence that suggests the opposite relationship between the ASR and mating-related behaviours also exists, e.g. that a female-biased sex ratio might either be associated with earlier [11] or later [13] ages of women's first birth. With regards to violence, it has been found that male–male violence is lower when men are in excess [14], and that male mortality from violence and risk-taking is not higher when men are plentiful [15], challenging the idea that more men leads to more violence. Thus, there is still some debate around whether a male- or female-biased ASR leads to greater pair-bond stability, commitment and parental care.

One potential explanation for the varying results, at least in the human ASR literature, is that studies come from populations that vary in ecological and cultural context. The consequences of ASR imbalance are being examined across a range of societies and several examples of this diversity are included in this issue: hunter–gatherer populations where population sizes are small and the ASR can be highly fluctuating [16], historical populations with strict marital norms where reproduction took place within the confines of marriage [13], contemporary societies with high economic inequality such as China [17], or where the ASR differs between sub-groups within a population, as is the case with race in the US [18]. Across many animal species, and in humans in particular, the social context influences the relative pay-offs to mating decisions. Anthropologists working within the framework of human behavioural ecology have long recognized that local costs and benefits that impact individual reproductive strategies can come in the form of sociocultural norms [19]. For instance, behavioural responsiveness to partner availability could be very sensitive to social sanctions or acceptance related to divorce and remarriage. Moreover, the role of men in childcare and the economic autonomy of women may further affect sex-specific behavioural responses to a shortage or surfeit of partners. Thus, paying greater attention to what Schacht and Smith [13] refer to as the ‘culturally mediated mating arena’ is essential to understand the reasons why ASR responses are not uniform across societies.

A second important factor explaining why there are mixed results in the human ASR literature is that studies vary greatly in their methodology and are often based on aggregated data with varying degrees of sophistication. While the ASR itself is by necessity a population-level variable, when the ASR is aggregated at a high level or the outcome variable is aggregated into a rate, several issues arise. First, when the ASR is calculated at a high level (e.g. country- or state-level), this can conceal vast local variation in mate availability and is unlikely to capture individuals' actual likelihood of finding a partner. Second, ASRs at the country- or state-level often have skewed distributions with extreme values; decisions on how to treat outliers can impact overall results [20]. Third, when the outcome variable is aggregated into a rate, this invokes issues related to the ecological fallacy, i.e. incorrectly drawing conclusions about individual behaviour based on group-level data. For example, a recent study reported an association between higher homicide rates and female-biased sex ratios at the county-level in the US [14], which might imply that men respond to partner surplus, not partner scarcity, with more violence. However, this methodology does not shed light on how the ASR affects individual strategies. While mapping population-level patterns can sometimes be useful, if the research question concerns individual strategies as responses to the ASR, the outcome variable too should be measured at this level (see [20] for further discussion).

A third contributor to the lack of clarity in the literature is that individual variability in response to partner availability is under-studied and under-appreciated. Which strategy to pursue when attempting to attract a prospective mate, or the relative pay-offs from staying in a pair-bond versus deserting a mate, should depend on an individual's particular traits and his or her mate value. All men or all women should not be expected to respond in the same way to mate scarcity or surplus. Heterogeneity in response to the ASR can be understood in terms of reaction norms, i.e. that individuals will vary in their response to the ASR because of their phenotype. For example, when the ASR is male-biased, an individual who is likely to be successful in a contest interaction due to greater physical prowess might opt for violence when competition for mates is high, whereas someone who has potential to attract mates through resources might instead invest in provisioning activities or increase the level of parental investment. Evidence of heterogeneity in ASR responses can be found among black striped pipefish (Syngnathus abaster); smaller females compete more vigorously under a female-biased sex ratio, when males are increasingly rare, whereas larger females, who are more desirable as mates, do not alter their behaviour [21]. In humans, single men are more likely to be involved in fatal violence and accidents than partnered men but only if they are of low socioeconomic status (SES) [22]. In other words, although some single men might compete through violence or risk-taking behaviours, this strategy may be less common among men who can compete with resources.

Thus, one factor that is likely to play a part in heterogeneity in responses to partner scarcity is access to resources. Research on mate preferences in Western contexts tends to show that individuals, and men in particular, with resources are more desirable as long-term mates, have more stable pair-bonds and invest more in their offspring than men with fewer resources [23,24]. Because women invest more in offspring through gestation and lactation, they are expected to select men who have high investment potential, whereas men are expected to prioritize indicators of female fertility (e.g. youth and health) because women's reproductive value declines with age [25]. However, in many developed and urban contexts where joint incomes are necessary for household functioning, and the perceived amount of resources needed for raising offspring is ever-increasing [26], resource holding is an advantage in a potential partner regardless of sex. Thus, assuming that, all else equal, an individual with higher resource access has higher status and is more attractive to the opposite sex, he or she will have higher bargaining power on the mating market and in a pair-bond. Consequently, both socioeconomic factors (here measured by education and social class) and the local ASR shift the conditions of individuals with potential implications for mating and parenting behaviours. It is therefore important to test how an individual's characteristics interact with the pressures imposed by the local sex ratio, and to consider behaviours of both individuals who are seeking mates and those who are in established pair-bonds, as we do in this study.

Lastly, research on the effects of the ASR has thus far placed greater emphasis on the behavioural responses of males than those of females. In the human literature, this male-centric view might be linked to the belief that it is the undesirable behaviours of men as a response to mate scarcity that contribute to societal problems. On an ultimate level, this might be related to the fact that in humans—as in all other mammals—maternal care is obligate through gestation and lactation, reducing women's potential flexibility in sex role-related behaviours [27]. However, it is incorrect to assume that females do not exercise flexibility in mating-related behaviours; females too resort to violence, competition, promiscuity and other behaviours with impact on family stability [28]. For instance, having multiple partners, generally taken to be a fitness advantage only for males, can incur benefits in terms of higher offspring survival for both female primates and women [28–31]. Because it is difficult to know what underlies the relationship between the ASR and mating behaviour and because responses to the ASR might not be symmetrical [32], behaviour of both sexes should be examined in unison.

2. Aims of the study

We use census data from Northern Ireland to test how the ASR is associated with mating and parenting behaviours. Northern Ireland is well-suited to studying the effects of the ASR because there are several female-biased and several male-biased local areas of residence. This balance of ASR areas is rare in the literature, so commonly focused on male-excess. Moreover, we use detailed migration data to show how the ASR skew arises and then consider how the ASR affects pair-bonding and parental investment for individuals of different social status.

This study has at least three key strengths, (i) we explore three different mating-related behaviours (cohabitation status, relationship stability and parental investment) that offer complementary insights into ASR response, (ii) we use detailed census data with a wide ranging ASR measured at the local ward-level, and (iii) we explicitly consider individual heterogeneity in ASR responses by SES, and examine behaviours of men and women simultaneously.

Below we lay out our predictions regarding the effects of SES, the ASR, and the interaction between the two on pair-bonding (cohabitation and separation) and parental investment.

3. Predictions

(a). The effect of socioeconomic status on pair-bonding

If individuals of high SES are more desirable as mates, they should be more likely to be in a long-term pair-bond (be cohabiting/have lower likelihood of separation) than low SES individuals.

(b). The effect of adult sex ratio on pair-bonding

lf females have higher fitness pay-offs from being in a stable pair-bond than males, and females have greater bargaining power under male-biased ASR, then males should be more willing to commit to a pair-bond for longer when the sex ratio is male-biased (i.e. both sexes should be more likely to be cohabiting/have lower likelihood of separation).

(c). The effect of adult sex ratio on pair-bonding should depend on socioeconomic status

If a skewed ASR means that the mate-limiting sex can increase demands on prospective mates, and having high SES is one such demand, the effect of the ASR on pair-bonding (higher cohabitation/lower separation) should be stronger for individuals of low SES than high SES.

(d). The effect of adult sex ratio on parental investment should depend on socioeconomic status

If a male-biased ASR increases female demands for male parental investment, and having lower SES means individuals have to compete harder to maintain a pair-bond, the positive effect of the ASR on parental investment should be stronger for low SES men than high SES men.

4. Data and methods

(a). Data

The Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study (NILS) links administrative data including the national Census to vital events, such as births and migration. NILS comprises approximately 28% of the Northern Irish population, randomly selected by 104 birthdays. A range of individual covariates are linked from the 2001 and 2011 Censuses and any missing data are statistically imputed by the Census (for a more detailed description of the NILS, see [33]). In order to establish how local ASR skews arise, we make use of the detailed migration data from the Business Services Organisation [33].

(b). Independent variables

To construct the ASR we used data from the Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service (NINIS) on ward-level population by sex and age. A ward is an administrative area that comprises approximately 2900 individuals, of which there are 582 in Northern Ireland.

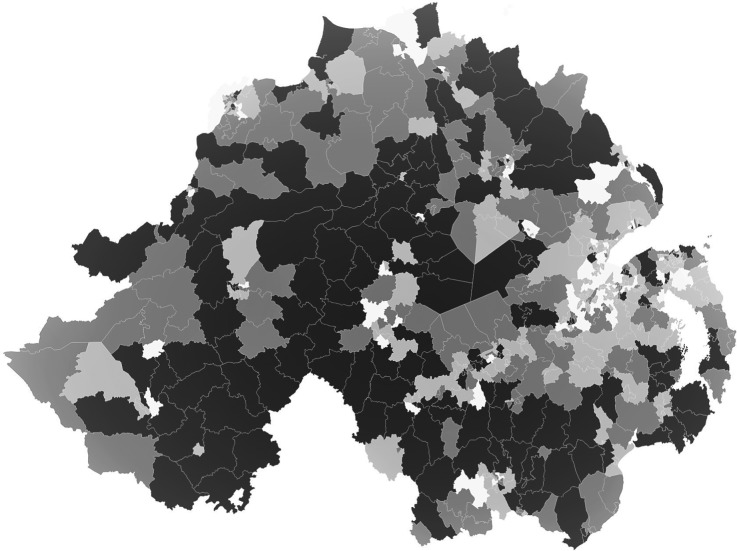

The ASR is based on individuals aged 16–39 years because we are interested in individuals of roughly reproductive age. Note that the ASR based on individuals aged 16–64 years is correlated to our measure at r = 0.94 (p < 0.001) and the ASR of 16 and over at r = 0.83 (p < 0.001). The ASRs of 16–39 year olds in 2001 and 2011 were correlated at r = 0.60 (p < 0.001). We categorized the ASR into quartiles because this was a better fit than other categorizations (e.g. tertiles, quintiles and sixtiles) and because it allows for easier interpretation (see table 1 for ranges). Because different practices exist in the ASR literature, we present both the proportion of males, which is the measure used throughout this issue, and the ratio of men to women side by side (table 1). For a map of Northern Ireland with the ASR in 2001, see figure 1.

Table 1.

Ranges of the ward-level adult sex ratio in 2001 (age 16–39 years) expressed as proportion of males (males/total population), and as adult sex ratio (men/women), by quartiles.

| 1st quartile | 2nd quartile | 3rd quartile | 4th quartile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| proportion males | 0.39–0.482 | 0.485–0.49 | 0.50–0.51 | 0.52–0.68 |

| ratio men : women | 0.64–0.93 | 0.94–0.98 | 0.99–1.05 | 1.06–2.08 |

Figure 1.

Map of the ward-level ASR in 2001 in Northern Ireland (proportion of males in parentheses). White—1st quartile (0.390–0.482), light grey—second quartile (ASR 0.485–0.490), dark grey—3rd quartile (ASR 0.500–0.510), black—4th quartile (ASR 0.520–0.680).

All individual independent variables were taken from the NILS and linked from the 2001 Census. Among our sample of 25–59 year olds, 60% lived in urban areas, 43% were Catholic, 55% Protestant and 2% reported having no/other religion. 39% had no qualifications, 20% GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education, taken at age 16), 15% GCSE+, 7% A-level, and 19% had a university degree. In the UK students take examinations in a range of subjects at GCSE-level after 5 years of secondary education; after an additional 2 years of study, students may take A-level examinations (required for university entrance). Father's social class (NS-SEC) is based on the 2002 classifications: ‘higher managerial and professional occupations’, ‘lower managerial and professional occupations’, ‘intermediate occupations’, ‘small employers and own account workers’, ‘lower supervisory and technical occupations’, ‘semi-routine occupations’, ‘routine occupations’ and ‘never worked or long-term unemployed’.

(c). Dependent variables

(i). Cohabitation

To test the effect of the ASR on cohabitation (a proxy for a stable pair-bond), we used data on cohabitation status (cohabiting versus non-cohabiting) of NILS members on Census day on the 29th of April 2001. We used cohabitation rather than marital status as a measure of a stable pair-bond so as to not exclude non-married individuals who live together in long-term relationships. This group is non-negligible; in 2001 33% of couples who had a child were not married. The sex of the partners of NILS members is not known here and so our analyses include all individuals regardless of the sex of their partner. Analyses for cohabitation and separation were restricted to individuals aged 25–59 years in 2001. The lower age cap was imposed because we are examining interactions with highest educational level and therefore we exclude individuals who might not yet have completed their education. Moreover, by excluding the under 25s we avoid including teenagers and young adults who might not yet wish to or are not yet able to live with a partner. Age was capped at 59 years because we are interested in individuals of roughly reproductive age.

(ii). Separation

The 2001 and 2011 Censuses were used to examine whether an individual transitions from a pair-bond to singlehood during this 10-year period. The transition to singlehood (henceforth separation) is a good measure for pair-bond stability because it enables us to estimate statistically the risk of ending up without a partner among those who have previously been both willing and able to establish a pair-bond. Individuals of the same age range (25–59 years in 2001) were used for the reasons described above.

(iii). Parental investment

To examine the level of parental investment of fathers as a function of the ASR, we used data on whether the father of a child was cohabiting with its mother (registered at the same address) at the time of the birth of the child. While we cannot know the reasons why the parents are not living together or who deserted whom, cohabitation is a useful measure of minimum male parental effort. Parental separation during early childhood has previously been used to infer a lower level paternal care [34]. We have data on 28 955 mother–father pairs where the women had their first birth between the years 2001 and 2013. In a fifth of these births the father was not registered at the same address as the mother at the time of the birth. Data on the father's social class were available regardless of whether the father was named by the mother on the birth certificate, thus limiting bias.

(d). Methods

We first explored how the ASR skew arises by running logistic regression models for risk of migrating from a ward, by sex and individual and area characteristics. For our three main outcomes—cohabitation, separation and parental investment—we ran multilevel logistic regressions where individuals (level 1) were clustered within wards (level 2). The random intercept for ward controls for unmeasured variation at the local ward-level. For cohabitation and separation models, interaction terms between the ASR and an individual's highest level of education were added to determine whether the effect of the ASR varied with social status. For parental investment models, we used data on father's social class, as this is a more detailed measure than highest educational level and is more variable over the life course. (Note that only educational level was available for the analyses on cohabitation and separation). In the analysis on parental investment, we controlled for father's age and age squared, as age might otherwise confound any effects of father's social class. Mother's age and social class were not included due to collinearity. The ASR used in parental investment models is based on the mother's residential ward at the time of the birth.

We excluded 13 wards where an army base was situated as these areas have highly male-biased ASR, and 12 wards along the north coast that were very scarcely populated, yielding 557 wards in our sample in total. Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to infer model fit, where a decrease in AIC of more than 2 units implies a better fit [35]. Maximum likelihood was used as estimation method, and for the figures we calculated the predicted probabilities. All analyses were performed in Stata 14.

5. Results

(a). What causes the adult sex ratio skew?

A skew in the ASR can arise because of biased sex ratios at birth, sex differences in mortality or in migration patterns. In addition, factors such as incarceration rates of males might lead to skewed sex ratios in some human populations. Because levels of incarcerations were low in Northern Ireland at the time of the study, male deaths (relative to female deaths) not as dramatic as in for example US populations [36] and the sex ratio at birth was not skewed [37], sex-biased migration is a more plausible explanation for the variation in ASR. Results from our logistic regression models based on migration data within Northern Ireland show that women were significantly more likely to out-migrate from certain types of areas and that this impacted the ASR. Overall, 51.8% of women out-migrated from their ward at least once during the study period, compared to 47.6% of men. Women were more likely than men to leave rural areas, areas with higher ward-level deprivation, areas with lower population density and areas with a male-biased sex ratio (see electronic supplementary material, table S1). Women were most likely to migrate if never married, whereas men were most likely to migrate when separated or divorced (see electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Lastly, we examined the degree of ASR skew of the wards individuals migrated to. Women who moved from male-biased areas to female-biased areas were more likely to migrate to a more strongly female-biased area than men (see electronic supplementary material, tables S2 and S3).

(b). Cohabitation and separation

The tables above show the percentage of cohabiting individuals and separations between 2001 and 2011 by ASR quartiles (table 2) and highest educational level (table 3). Overall, 67% of women in the most female-biased areas were cohabiting with a partner compared to 81% of women in the most male-biased areas. Approximately 23% of men and women in the most female-biased areas experienced separation, compared to ca. 16% in the most male-biased areas. Among men and women with the highest level of education, 15 and 16% separated during the study period, compared to ca. 21% and 23%, respectively, of those with the lowest level of education (table 3).

Table 2.

Percentage of the sample who were cohabiting with a partner (in 2001) and who experienced separation from a partner (between 2001 and 2011) by ASR of area of residence in 2001, individuals aged 25–59 years in 2001; men n = 69 117, women n = 71 685.

| 1st quartile (%) | 2nd quartile (%) | 3rd quartile (%) | 4th quartile (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cohabitation | ||||

| men | 77.2 | 81.0 | 80.1 | 78.0 |

| women | 66.7 | 75.4 | 77.9 | 80.5 |

| separation | ||||

| men | 22.7 | 18.4 | 17.8 | 16.3 |

| women | 23.3 | 19.3 | 18.9 | 16.4 |

Table 3.

Percentage of the sample who were cohabiting with a partner (in 2001) and who experienced separation from a partner (between 2001 and 2011) by highest level of education, individuals aged 25–59 years in 2001; men n = 69 117, women n = 71 685. Degree—university degree or higher. No qual.—no qualifications.

| degree (%) | A-level (%) | GCSE+ (%) | GCSE (%) | no qual. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cohabitation | |||||

| men | 81.0 | 76.3 | 79.7 | 78.1 | 79.5 |

| women | 74.9 | 75.8 | 78.7 | 74.3 | 73.2 |

| separation | |||||

| men | 15.3 | 17.2 | 17.9 | 19.7 | 20.5 |

| women | 16.4 | 18.0 | 17.5 | 19.3 | 22.5 |

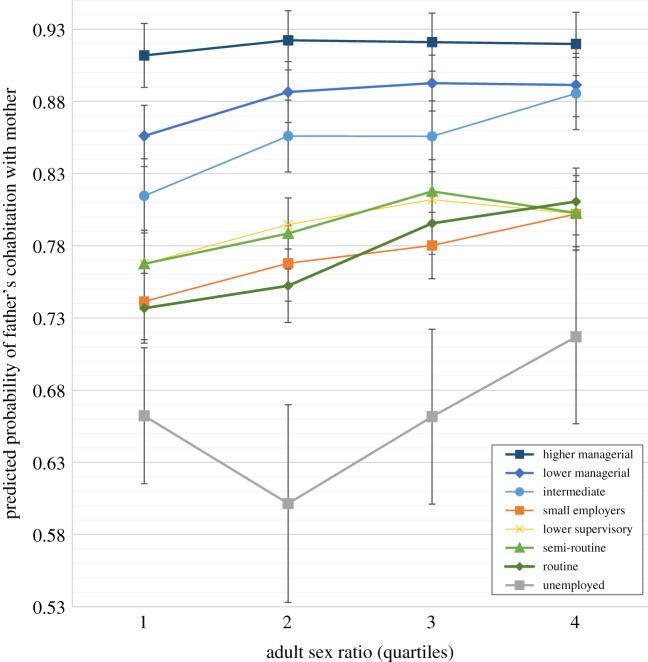

In multilevel logistic regressions we found evidence that men with high education were more likely to cohabit with a partner (figure 2a). This offered some support for our first prediction. However, the relationship was not dose-dependent; men with no qualifications were less likely than men with any other educational level to cohabit with a partner, but other groups appeared similar. Notably, the results showed no significant effect of the ASR among men of any educational group (figure 2a). Thus, neither prediction 2, that men should be more likely to be in a stable pair-bond under male-biased sex ratios, nor prediction 3, that the effect of ASR should be stronger among men with lower education, were supported for males (for full model and coefficients, see electronic supplementary material, table S4).

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of cohabitation with 95% confidence intervals, by highest level of education and adult sex ratio among men (a) and women (b) between the ages of 25–59 years. Based on multilevel logistic model, controlling for age, age squared and religion (Catholic, Protestant, none/other), with individuals men (n = 87110, women n = 95 673) (level 1) clustered within wards (level 2, n = 557).

We found evidence that under female-biased sex ratios, women without any formal education were less likely to be cohabiting with a partner compared to more educated women. But under male-biased sex ratios, there was no significant difference in the probability of cohabiting with a partner between women with a university degree and those without any education (figure 2b, and electronic supplementary material, table S4). In other words, there was a positive effect of the ASR on female cohabitation (supporting prediction 2), and this effect was strongest among women with low levels of education (supporting prediction 3). Prediction 1, that high education should be associated with higher probability of being in a pair-bond, was only partially supported.

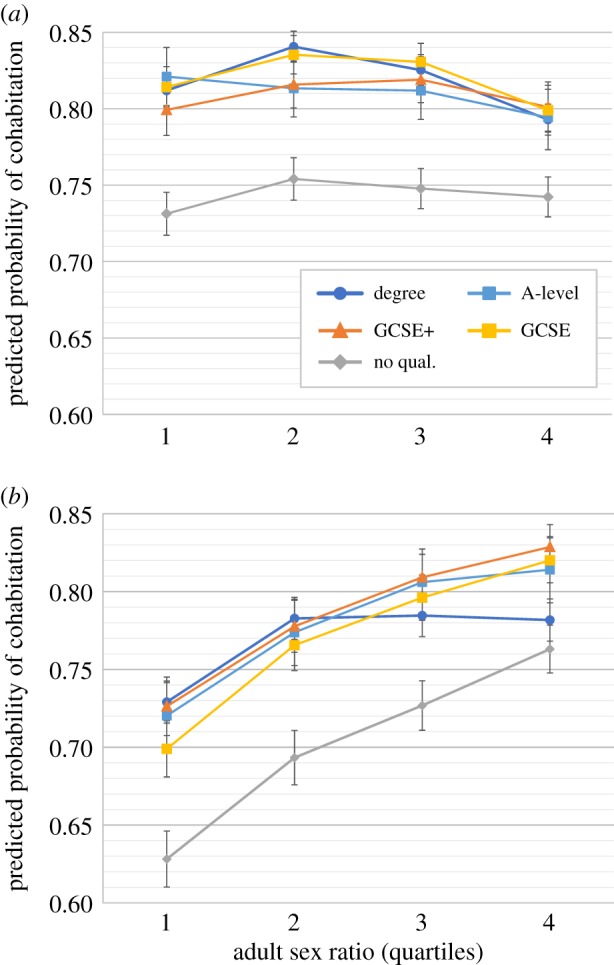

In the models on separation, there was evidence that men and women with a university degree were less likely to end up as single compared to peers with no qualifications. Other educational categories fell in between, according to their level. Second, separation was more likely to occur at female-biased sex ratios among individuals with both the highest and lowest levels of education (figure 3a,b). Third, the effect of the ASR was only marginally stronger for individuals with the lowest educational category (no qualifications) compared to those with the highest. Thus while our first two predictions were supported, there was only tentative support for the third.

Figure 3.

Predicted probability of separation (likelihood of transition from a pair-bond to singlehood between 2001 and 2011) with 95% confidence intervals, by highest level of education and adult sex ratio among men (a) and women (b) between the ages of 25–59 years. Based on multilevel logistic model, controlling for age, age squared and religion (Catholic, Protestant, none/other), with individuals (men n = 69117, women n = 71 685) (level 1) clustered within wards (level 2, n = 557).

(c). Parental investment

Tables 4 and 5 show the percentage of fathers who were cohabiting with the mother at the birth of their child. There was a large difference in parental investment with the father's social class: 42% of fathers who had never worked/were long-term unemployed were cohabiting with the mother, compared to 96% of fathers who had a higher managerial or professional occupation (table 4). In female-biased areas, 39% of fathers who had never worked/were long-term unemployed cohabited with the mother, compared to 52% of their peers in the most male-biased areas. Among men with the highest social class, cohabitation with the mother was around 95% both in the most male-biased and most female-biased areas (table 5).

Table 4.

Percentage of couples where father and mother were cohabiting at the time of the birth of the child, and father's and mother's mean age, by father's social class. n = 28 955 couples.

| father's social class | n | cohabitation (%) | father's age mean (s.d.) | mother's age mean (s.d.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| higher managerial and professional | 3848 | 95.7 | 34.2 (5.3) | 32.2 (4.5) |

| lower managerial and professional | 4284 | 91.1 | 33.3 (5.9) | 31.0 (5.0) |

| intermediate occupations | 2981 | 85.7 | 32.3 (6.3) | 30.2 (5.3) |

| small employers and own account work | 466 | 77.2 | 32.1 (6.6) | 29.3 (5.8) |

| lower supervisory and technical | 3400 | 77.6 | 30.9 (6.3) | 28.7 (5.6) |

| semi-routine occupations | 4033 | 73.6 | 30.4 (6.5) | 27.9 (5.7) |

| routine occupations | 4776 | 74.0 | 31.1 (6.5) | 28.4 (5.7) |

| never worked/long-term unemployed | 927 | 42.2 | 27.5 (7.4) | 24.3 (6.0) |

Table 5.

Percentage of couples where the father and mother were cohabiting at the time of the birth of their child, by father's social class and the adult sex ratio of mother's residential ward, n = 28 955.

| father's social class | 1st quartile (%) | 2nd quartile (%) | 3rd quartile (%) | 4th quartile (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| higher managerial and professional | 94.9 | 96.1 | 96.2 | 95.5 |

| lower managerial and professional | 87.3 | 92.6 | 92.4 | 92.2 |

| intermediate occupations | 80.0 | 87.1 | 87.4 | 89.6 |

| small employers and own account work | 67.6 | 78.0 | 78.7 | 82.9 |

| lower supervisory and technical | 70.1 | 79.3 | 80.1 | 80.6 |

| semi-routine occupations | 66.6 | 75.4 | 78.3 | 76.6 |

| routine occupations | 65.4 | 73.4 | 77.7 | 80.7 |

| never worked/long-term unemployed | 38.8 | 41.4 | 41.4 | 51.7 |

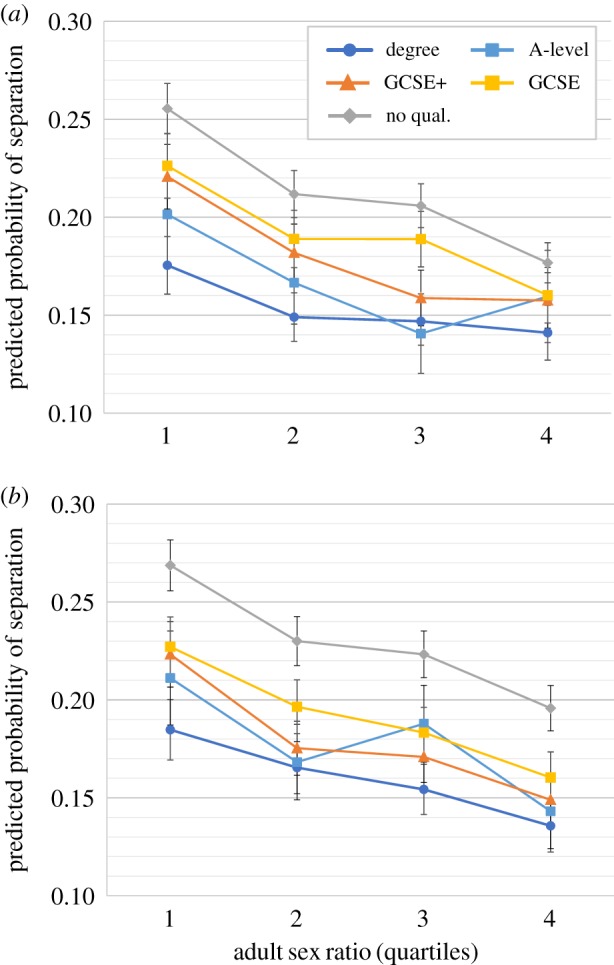

Figure 4 shows the results of a multilevel logistic regression with the predicted probabilities of the father cohabiting with the mother at the time of the birth of the child, by father's social class and the ASR of the mother's residential ward. As predicted, fathers of higher social class were more likely to exhibit parental investment and overall there was a positive effect of the ASR on parental investment. Men belonging to several of the lower social classes, but not all, were somewhat more likely to live with the mother of their child in a male-biased area than in a female-biased area. However, the parental investment of men with higher social class appeared not to be associated with the ASR. These results thus offer support for prediction 4, though the effects varied between the lower social class categories and not all were significant.

Figure 4.

Predicted probability of parental investment (father's cohabitation with the mother at the birth of the child) by father's social class and adult sex ratio of mother's residential ward. Based on multilevel logistic regression controlling for father's age, father's age squared and religion (Catholic, Protestant, none/other), with couples (level 1, n = 28 955) clustered within wards (level 2, n = 557).

(d). Individual and ward-level variance

We calculated the variance partition coefficient (VPC) to examine the percentage variance of the total variance in the outcome that can be attributed to the ward-level, with the remaining variance at the individual-level [38]. For cohabitation the ward-level was responsible for 4.6 and 5.2% of the variance in male and female cohabitation, respectively. The corresponding figures for separation were 1.7 and 1.2% for men and women, respectively, whereas for parental investment the variance explained by the ward-level was 10.7% (see also electronic supplementary material, tables S4–S6).

6. Discussion

We have explored the effect of the ASR on mating and parenting behaviours in a developed population with a wide range in the local ASR. The results demonstrate that the effects of the ASR on cohabitation, separation and parental investment are contingent both on sex and social status. This is a novel contribution as the literature to date has put little emphasis on how facultative responses to the ASR might vary both in type and magnitude based on an individual's status and bargaining power within the mating market. Moreover, previous studies have often used ASR on country- or state-level and paid less attention to female than male responses to mate scarcity. Our data reinforce previous empirical evidence from humans that shows that males might not compete more violently when there is an excess of males [14,15]. Instead, men who want to woo or keep a partner when competition is high might signal their intention to invest and become more engaged in parental investment. Below we discuss the results in relation to previous literature, and identify areas where results are contradictory or seemingly at odds with any one straightforward theoretical explanation.

The results offer support for the prediction that men of high SES should be more likely to cohabit with a partner, but there was no evidence that the effect of ASR on male cohabitation varied with male SES. This was surprising, as we had predicted that females would increase income-related demands on prospective mates under male-biased sex ratios. These results contrast with those of Pollet & Nettle [39], who found that the effect of SES on marriage success was stronger in male-biased states in a historical US sample, possibly as a result of higher female demands on male provisioning in areas where men were more plentiful. It is difficult to ascertain whether the differences between Pollet and Nettle's and our study stem from differences in methodology, in particular the coarse nature of the US state-level ASR, and/or if they are due to differences in sociocultural context. In early twentieth century US, childbearing took place within the confines of marriage, whereas in present day Northern Ireland, social sanctions on divorce are less severe, childbearing out of wedlock or even among parents who are not cohabiting is common, and some state benefits are available for single parents if needed. One potential explanation is thus that selecting a partner with high wealth is less critical for women in our study. While it is intuitive that women can drive a harder bargain when men are plentiful, and vice versa, these results are not so straightforward. In line with our predictions, we did however find a (weak) interaction between the ASR and SES in our models based on couples with children, and for female cohabitation, and we discuss possible reasons for these differences below.

For women we found a positive effect of the ASR on the likelihood of cohabitation with a partner and that a male-biased ASR increased the likelihood of cohabitation, particularly for women with low education. One interpretation is that men in female-biased areas are low investors and that women in such areas, and especially women with the lowest education, are better off not being partnered at all. Women can benefit from mating with multiple men and could do better by not committing to a single partner [30,31], for example if he is a burden rather than someone who will reliably invest in offspring. We have previously shown that it is the women in female-biased areas and women of low SES who start reproducing early in this population, often without the support of a partner [11]. Because abortion is illegal in Northern Ireland, risky (unprotected) sex, which has been shown to be more common in female-biased areas [18], might lead to early parenthood for these women more often than if abortion were legal and more easily accessible.

Some of the asymmetries between the male and female cohabitation models are likely to be explained by the fact that men in female-biased areas could opt for women younger than the age cut-off at 25 years that we used in these analyses. Women in female-biased areas might accept a man with relatively low SES (even in male-biased areas) if these costs are outweighed by the perceived benefits associated with an older-aged man. Nevertheless, it was somewhat surprising that highly educated women, who might find it easier than women with lower education to find a partner willing to commit, were not cohabiting with a partner to a higher extent than what was observed. One explanation might be that a high SES woman might not necessarily be the first choice for a man in a female-biased area, as he might struggle to meet her higher demands on investment. How satisfied individuals are in their relationship is not only affected by how well their mate fulfils their mate preference but also by the discrepancy in mate value between themselves and their partner [40]. Thus, rather than lowering their demands, high SES women might favour a strategy where they delay family formation until a higher-quality mate is around and in the meantime focus on their career. This resonates with some experimental evidence that when women are exposed to cues of a female-biased sex ratio, they are more likely to prefer career investments over family formation [41] and evidence that birth rates of the over 30s are higher in affluent female-biased wards whereas birth rates at younger ages are higher in deprived female-biased wards in England and Wales [42].

Our results showed that separation was more common among individuals with low education and under female-biased sex ratios in both sexes. However, the difference in the effect of the ASR on separation based on education was slight and only marginally stronger among those with low education. It is possible that men with low education might start behaving more like highly educated men and stay with partners for longer when competition for mates is high. By necessity, the relationship between the ASR and the separation risk cannot differ in the two sexes as it takes two to separate, and by definition, cohabiting couples reside in the same ward prior to separation. Instead, in order to understand the dynamics that precede separation, behaviours that can be indicative of effort/disinvestment in the relationship could be examined. Time spent on household chores is one such behaviour that has been linked to relationship satisfaction and likelihood of separation [43] and could be compared for women and men to understand negations within the pair-bond when one sex outnumbers the other.

For parental investment, men with low levels of resources, who tend to have a faster life-history strategy and would generally be more likely to desert a woman, seem to opt for a strategy of increased parental investment when surrounded by many other men. Interestingly, these results show that even among relatively high status men, there was an effect of the ASR on parental investment. In female-biased areas, men with intermediate occupations were less likely than higher managerial/professional men to live with their offspring, but in male-biased areas, these men had ‘caught up’ with men with the highest social class. It should be noted that results were not uniform across all eight categories of social class and the magnitude of the ASR effect was in some cases weak or not significant. Parental cohabitation captures a base-level parental investment and future work should examine whether this pattern holds for more detailed parental investment measures. A related question is how women respond to men's parenting behaviour: in male-biased areas, do women start investing less in offspring and more in their own income generating activities? Or do women invest in offspring regardless but instead spend less time and effort on other demands of partners (e.g. investment in housework or physical appearance)? Some historical evidence from the US suggests that women were less likely to be in the workforce when the ASR was male-biased [44], but this study relied on aggregated data and the pattern might not hold for contemporary populations in which women are less dependent on men for resources. Understanding the different forms that ASR responses might take in each sex is important in order to predict societal consequences of sex ratio imbalances, and to get a better insight into how the behaviour of one sex influences the behaviour of the other.

Sex-biased migration patterns were the root cause of the variation in ASR in our population; women were more likely to migrate from areas that were scarcely populated and deprived. As more detailed data from a range of populations are now being deployed, the question of how stable ASRs are is starting to be investigated. Incorporating not only the absolute level of the ASR but also its variation over time could be important; the unpredictability of finding a mate might influence behaviour differently from a situation in which individuals can make a reliable ‘forecast’ of their chances. In populations where individuals have multiple options for employment and residence and the geographical distances between rural villages (often male-biased) and cities (often female-biased) are small, as in Northern Ireland, men might eschew mate scarcity by following women who move to urban areas for education or employment. Whether this is a strategy men pursue might depend on how skewed the ASRs are and the economic opportunities men have in different types of areas.

It is possible that low SES individuals in male-biased areas might differ in some ways compared to low SES individuals in female-biased areas. For example, individuals in male-biased areas might be faced with a more conservative community, where deserting a partner would be associated with stronger social sanctions than in female-biased areas. Furthermore, it might be easier to keep track of one's partner in rural areas if communities are more tight-knit and anonymity lower. This is important because for the ASR to influence the degree of sexual selection that is operating in a population, mate monopolization has to be strong [45]. The assumption of strong monopolization might be questioned in developed populations where both sexes spend a considerable amount of time outside the home in employment, and there are plenty of opportunities to meet new partners.

We have assumed that the ward is a meaningful boundary at which to measure the ASR. Although there are other means to find a partner than within one's local ward, individuals tend to marry others who are similar to themselves who are likely to live nearby [46] and characteristics from an individual's local ecology might serve as cues to one's prospect of finding a mate even outside the ward. Because Northern Ireland has high levels of residential segregation, the sense of local community is strong. Drawing on this, we recently tested how well individuals' perceptions of neighbourhoods in Belfast matched the actual ecological characteristics. We found evidence that most individuals perceived themselves to live in slightly female-biased areas even when they lived in areas where males clearly outnumbered females [47]. While it is not necessarily assumed that individuals are consciously aware of the local ASR, these results raise questions about the mechanisms by which the ASR affects human behaviour. Because of homogamy, i.e. that individuals tend to assort with partners similar to themselves with regards to, for example SES, it is possible that individuals pay more attention to potential partners of their own SES. Thus, future work that considers the ASR based on sub-groups within a population, such as SES, rather than overall ASR, might have higher predictive power.

In conclusion, findings presented here are in line with theoretical models and some recent empirical evidence from non-human species that show that male-biased sex ratios are associated with greater pair-bond commitment [5,48]. We show that there is heterogeneity in this effect and that the impact of mate scarcity varies with social status. Our measures of education and social class as proxies for mate value and social status are just one dimension of mate desirability and many others might also be worth investigating (e.g. physical attractiveness and personality traits). Other factors related to the reproductive value of the individual, such as age or parity, might also impact the effect of the ASR, as mate scarcity would have different fitness implications for individuals who have had many offspring compared to those who have had none. Future analyses should capture multiple outcomes per individual, as this would allow assessment of whether multiple strategies are pursued in the face of mate scarcity, or whether individuals tend to increase investment in one particular strategy. While most human ASR studies focus on male behaviour, we have compared behaviour of both sexes and found evidence that ASR responses in Northern Ireland are not symmetrical for commitment to a pair-bond. Whether it is the men or the women who dictate the terms in a population could vary with social institutions, economic independence of women, how flexible pair-bonds are, and how mate monopolization occurs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ryan Schacht, Peter Kappeler, two anonymous reviewers and the participants of the ASR workshop at the Wissenschaftskolleg for comments and critique. This research would not be possible without the assistance of the Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study (NILS) and NILS Research Support Unit. The NILS is funded by the Health and Social Care Research and Development Division of the Public Health Agency (HSC R&D Division) and NISRA. The NILS-RSU is funded by the ESRC and the Northern Irish Government.

Ethics

Our study received ethics clearance from the NILS Research Support Unit.

Data accessibility

The data are publicly available upon successful application to the Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study.

Authors' contributions

C.U. and R.M. conceived and designed the study; C.U. performed the analysis; C.U. and R.M. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was funded by the ERC (grant no. AdG 249347).

References

- 1.Rondeau A, Sainte-Marie B. 2001. Variable mate-guarding time and sperm allocation by male snow crabs (Chionoecetes opilio) in response to sexual competition, and their impact on the mating success of females. Biol. Bull. 201, 204–217. ( 10.2307/1543335) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linklater JR, Wertheim B, Wigby S, Chapman T. 2007. Ejaculate depletion patterns evolve in response to experimental manipulation of the sex ratio in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 61, 2027–2034. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00157.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlsson K, Eroukhmanoff F, Svensson EI. 2010. Phenotypic plasticity in response to the social environment: effects of density and sex ratio on mating behaviour following ecotype divergence. PLoS ONE 5, e12755 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0012755) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnqvist G, Rowe L. 2005. Sexual conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liker A, Freckleton RP, Székely T. 2014. Divorce and infidelity are associated with skewed adult sex ratios in birds. Curr. Biol. 24, 880–884. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.059) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guttentag M, Secord P. 1983. Too many women? The sex ratio question. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen FA. 1991. Secular trends in human sex ratios: their influence on individual and family behavior. Hum. Nat. 2, 271–291. ( 10.1007/BF02692189) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barber N. 2001. On the relationship between marital opportunity and teen pregnancy: the sex ratio question. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 32, 259–267. ( 10.1177/0022022101032003001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Khan MR, Schwartz RJ, Miller WC. 2013. Sex ratio, poverty, and concurrent partnerships among men and women in the United States: a multilevel analysis. Ann. Epidemiol. 23, 716–719. ( 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pouget ER, Kershaw TS, Niccolai LM, Ickovics JR, Blankenship KM. 2010. Associations of sex ratios and male incarceration rates with multiple opposite-sex partners: potential social determinants of HIV/STI transmission. Public Health Rep. 125, 70–80. ( 10.1177/00333549101250S411) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uggla C, Mace R. 2016. Local ecology influences reproductive timing in Northern Ireland independently of individual wealth. Behav. Ecol. 27, 158–165. ( 10.1093/beheco/arv133) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schacht R, Borgerhoff Mulder M. 2015. Sex ratio effects on reproductive strategies in humans. R. Soc. open sci. 2, 140402 ( 10.1098/rsos.140402) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schacht R, Smith KR. 2017. Causes and consequences of adult sex ratio imbalance in a historical U.S. population. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160314 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0314) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schacht R, Tharp D, Smith KR. 2016. Marriage markets and male mating effort: violence and crime are elevated where men are rare. Hum. Nat. 27, 489–500. ( 10.1007/s12110-016-9271-xMarriage) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uggla C, Mace R. 2015. Effects of local extrinsic mortality rate, crime and sex ratio on preventable death in Northern Ireland. Evol. Med. Public Health 1, 266–277. ( 10.1093/emph/eov020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer KL, Schacht R, Bell A. 2017. Adult sex ratios and partner scarcity among hunter–gatherers: implications for dispersal patterns and the evolution of human sociality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160316 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0316) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou X, Hesketh T. 2017. High sex ratios in rural China: declining well-being with age in never-married men. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160324 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0324) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pouget ER. 2017. Social determinants of adult sex ratios and racial/ethnic disparities in transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in the USA. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160323 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0323) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mace R. 2014. Human behavioral ecology and its evil twin. Behav. Ecol. 25, 443–449. ( 10.1093/beheco/aru069) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollet TV, Stoevenbelt AH, Kuppens T. 2017. The potential pitfalls of studying adult sex ratios at aggregate levels in humans. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160317 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0317) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva K, Vieira MN, Almada VC, Monteiro NM. 2010. Reversing sex role reversal: compete only when you must. Anim. Behav. 79, 885–893. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.01.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uggla C, Mace R. 2015. Someone to live for: effects of partner and dependent children on preventable death in a population wide sample from Northern Ireland. Evol. Hum. Behav. 36, 1–7. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.07.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray PB, Anderson KG. 2012. Fatherhood: evolution and human paternal behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nettle D. 2008. Why do some dads get more involved than others? Evidence from a large British cohort. Evol. Hum. Behav. 29, 416–423.e1. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.06.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trivers RL. 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual selection and the descent of man 1871–1971 (ed. Campbell B.), pp. 136–179. London, UK: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mace R. 2008. Reproducing in cities. Science 319, 764–766. ( 10.1126/science.1153960) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kappeler PM. 2017. Sex roles and adult sex ratios: insights from mammalian biology and consequences for primate behaviour. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160321 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0321) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hrdy SB. 1986. Empathy, polyandry, and the myth of the coy female. In Feminist approaches (ed. Bleier R.), pp. 119–146. New York, NY: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill K, Hurtado AM. 1996. Ache life history: the ecology and demography of a foraging people. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown GR, Laland KN, Borgerhoff Mulder M. 2009. Bateman's principles and human sex roles . Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 297–304. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2009.02.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borgerhoff Mulder M. 2009. Serial monogamy as polygyny or polyandry? Hum. Nat. 20, 130–150. ( 10.1007/s12110-009-9060-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Székely T, Weissing FJ, Komdeur J. 2014. Adult sex ratio variation: implications for breeding system evolution. J. Evol. Biol. 27, 1500–1512. ( 10.1111/jeb.12415) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Reilly D, Rosato M, Catney G, Johnston F, Brolly M. 2012. Cohort description: the Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study (NILS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 41, 34–41. ( 10.1093/ije/dyq271) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quinlan R. 2003. Father absence, parental care, and female reproductive development. Evol. Hum. Behav. 24, 376–390. ( 10.1016/S1090-5138(03)00039-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. 2002. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information–theoretical approach, 2nd edn New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson M, Daly M. 1997. Life expectancy, economic inequality, homicide and reproductive timing in Chicago neighbourhoods. Br. Med. J. 314, 1271–1274. ( 10.1136/bmj.314.7089.1271) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). Report: Northern Ireland live births, by sex 1987–2015.

- 38.Snijder TAB, Bosker RJ. 2011. Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling, 2nd edn London, UK: Sage Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pollet TV, Nettle D. 2008. Driving a hard bargain: sex ratio and male marriage success in a historical US population. Biol. Lett. 4, 31–33. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0543) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conroy-Beam D, Goetz CD, Buss DM. 2016. What predicts romantic relationship satisfaction and mate retention intensity: mate preference fulfillment or mate value discrepancies? Evol. Hum. Behav. 37, 440–448. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.04.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Durante KM, Griskevicius V, Simpson J A, Cantú SM, Tybur JM. 2012. Sex ratio and women's career choice: does a scarcity of men lead women to choose briefcase over baby? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 103, 121–134. ( 10.1037/a0027949) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chipman A, Morrison E. 2013. The impact of sex ratio and economic status on local birth rates. Biol. Lett. 9, 20130027 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruppanner L, Brandén M, Turunen J. 2016. Does unequal housework lead to divorce? Evidence from Sweden. Sociology 1–20. ( 10.1177/0038038516674664) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angrist J. 2002. How do sex ratios affect marriage and labor markets? Evidence from America's second generation. Q. J. Econ. 117, 997–1038. ( 10.1162/003355302760193940) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klug H, Heuschele J, Jennions MD, Kokko H. 2010. The mismeasurement of sexual selection. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 447–462. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01921.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haandrikman K, van Wissen LJG, Harmsen CN. 2011. Explaining spatial homogamy. Compositional, spatial and regional cultural determinants of regional patterns of spatial homogamy in the Netherlands. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 4, 75–93. ( 10.1007/s12061-009-9044-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilbert J, Uggla C, Mace R. 2016. Knowing your neighbourhood: local ecology and personal experience predict neighbourhood perceptions in Belfast, Northern Ireland. R. Soc. open sci. 3, 160468 ( 10.1098/rsos.160468) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kokko H, Jennions MD. 2008. Parental investment, sexual selection and sex ratios. J. Evol. Biol. 21, 919–948. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01540.xREVIEW) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are publicly available upon successful application to the Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study.